Introductory Info

Date introduced: 3 December 2020

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Environment

Commencement: Various dates as set out in this Bills Digest.

Purpose of

the Bills

This Bills Digest is for a legislative package of five

Bills, that is, the:

The purpose of this legislative package is to:

- establish

a national framework and nationally consistent standards to manage the environmental

risks of industrial chemicals, which will then be implemented by states and

territories and the Commonwealth within their own jurisdictions

- establish

a cost recovery model to implement the national framework and

- make

consequential and other minor amendments to the Industrial

Chemicals Act 2019.

Structure of

the ICEMR Bill

The ICEMR Bill is divided into six parts:

- Part

1 sets out preliminary provisions including the objects and definitions

- Part

2:

- establishes

the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management Register (the Register)

- enables

the Minister to make ‘scheduling decisions’ which assign industrial chemicals to

a schedule of the Register

- enables

the Minister to make decision-making principles which set out criteria for

scheduling decisions

- Part

3 establishes the Advisory Committee on the Environmental Management of

Industrial Chemicals

- Part

4 provides mechanisms for sharing and protecting information, and for the use

and disclosure of protected information in certain limited circumstances

- Part

5 deals with the administration of the scheduling charge imposed by the Charges

Bills, including liability for the payment of the charge and

- Part

6 contains miscellaneous provisions, including delegation provisions and provisions

which enable the Minister to make rules in relation to the proposed regime.

Commencement

| Bill |

Commencement |

| ICEMR Bill |

The day after Royal

Assent |

| Amendment Bill |

Sections 1–3 on Royal

Assent

Schedule 1 on the day

after Royal Assent

Schedule 2 on the later

of: the start of the day after Royal Assent and immediately after the

commencement of the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management

(Register) Act 2020. Schedule 2 will not commence if the Industrial

Chemicals Environmental Management (Register) Act does not commence.

Schedule 3 on the

later of: immediately after the commencement of the Industrial Chemicals

Environmental Management (Register) Act 2020 and immediately after the

commencement of the Federal Circuit

and Family Court of Australia Act 2020. Both these events must occur

for Schedule 3 to commence.

|

| Charges Bills |

The later of the

start of the day after Royal Assent and immediately after the commencement of

the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management (Register) Act.

However, these Bills will not commence if the Industrial Chemicals

Environmental Management (Register) Act does not commence. |

Background

Regulation of chemicals in

Australia

Chemicals introduced to Australia (whether through

importation or manufacture) are regulated through four federal schemes. The

schemes are divided by end use of the product. The four areas concentrate on:

As outlined in the ‘Key issues and provisions’ section of

this Digest, these Bills aim to build on the recent reforms to the regulation

of industrial chemicals by the Industrial Chemicals Act.[8] They follow a long process of

reform and consultation, as discussed further below.

History behind Bills

Productivity Commission report

In 2007, the Government announced that the Productivity

Commission would undertake a study into the regulation of chemicals and plastics.[9]

The Productivity Commission was asked to identify duplication and inconsistency

of those regulations within and across all levels of government in Australia.[10]

The Productivity Commission released its Research

Report on Chemicals and Plastics Regulation in August 2008. Chapter 9

of the report addressed the issue of managing the impact of chemicals on the

environment and found:

-

Chemicals have the potential to impact adversely on the

environment during their manufacture, use and disposal. Governments have a role

in intervening to ensure that the risks of adverse impacts are managed where

that is effective and efficient.

-

Governments have regulated to address the impact on the environment

of a number of chemicals with known hazards. However, a large

number of chemicals in use have not been subject to environmental (or other)

hazard and risk assessment.

-

There are some differences in the way that each state and

territory regulates for environmental protection, including with respect to

chemicals and plastics. This can reflect the different environments across

jurisdictions and the manner in which different regulatory regimes have

evolved.

-

The regulatory framework for managing the impact of chemicals on

the environment could be improved.[11]

Among other matters, the report recommended ‘the

establishment of a new environmental standard-setting body … to set nationally

consistent standards as necessary’, and that the states and territories should

uniformly adopt the standards by reference.[12]

Council of Australian Governments’ response

In November 2008, in response to the Productivity

Commission’s recommendations, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) requested

the Environment Protection and Heritage Council (EPHC) to progress a proposal

for establishing a standard-setting body for chemicals in the environment. COAG

noted that this would ‘close a significant gap in the current arrangements for

environmental protection’ and provide for a ‘single national decision on the

environmental management of chemicals which can be adopted by reference and

applied consistently in all jurisdictions’.[13]

Responsibility for this reform was transferred to the COAG

Standing Council on Environment and Water when it replaced the EPHC in 2011.[14]

In April 2013, the Standing Council released a Consultation

Regulation Impact Statement (RIS) on options for developing and implementing

nationally consistent decisions to manage the environmental risks of industrial

chemicals.[15]

This aimed to implement the reforms recommended by the Productivity Commission,

including the creation of a standards-setting body to develop national

environmental risk management decisions for industrial chemicals.[16]

According to the Department of Agriculture, Water and the

Environment (the Department), feedback from the RIS consultation process ‘was

used to refine the approach’ and options were presented for consideration by

Environment Ministers:

The preferred option was a cooperative framework including a

National Standard and decision powers established under Commonwealth

legislation. Automatic adoption under jurisdictional legislation would occur for

implementation and compliance.[17]

Environment Ministers decision

In July 2015, Commonwealth, state and territory

Environment Ministers agreed to establish a national standard to manage the

environmental risks of industrial chemicals.[18]

The Bill aims to ‘deliver on the approach agreed by environment ministers and

the recommendation of the Productivity Commission to fill this regulatory gap

through the National Standard’.[19]

In February 2018, the Meeting of Environment Ministers

noted ‘progress’ on the development of a National Standard for environmental

risk management of industrial chemicals:

The Commonwealth and states and territories have been

working collaboratively, and with close consultation with business and the

community, to develop the National Standard.

…

The Australian Government will commence drafting legislation

to establish this framework for protecting the health of our environment and

everything living in it.

All jurisdictions will continue to work together and consult

broadly during implementation of the National Standard to ensure we deliver the

best possible outcomes for governments, businesses and the community.[20]

Consultation on draft legislation

In January 2020, the Department released draft legislation

and supporting information for public consultation in February 2020.[21]

The supporting information explained that the draft legislation aims to build

on recent reforms to the regulation of industrial chemicals by the Industrial

Chemicals Act, and that the ‘ICEMR Bill has been designed to work in

conjunction with the mechanisms under the [Industrial Chemicals Act],

and to avoid duplication’.[22]

Eleven formal submissions were received.[23]

According the Department, feedback received during that process has been ‘incorporated

into the final legislative package’.[24]

Committee

consideration

Senate Environment and

Communications Legislation Committee

The Bills were referred to the Senate Environment and

Communications Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 11 March 2021. The

Committee received seven submissions. Issues raised in these submissions are

discussed elsewhere in this Digest. The Committee recommended that the Bills be

passed,[25]

but also made two other recommendations:

- that

the government and the Department ‘continue to actively engage state and

territory governments, particularly around planning for the adoption of the

Register in their respective jurisdictions’ (recommendation 1) and

- that

the Department continue its engagement with industry stakeholders in the

implementation of the Bills, ‘particularly with reference to the cost-recovery

arrangements and the role of Australian Industrial Chemicals Introduction

Scheme’ (recommendation 2).[26]

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

ICEMR Bill

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee has raised concerns that

the ICEMR Bill provides for a range of matters that are significant to the

operation of the proposed framework for managing industrial chemicals to be set

out in non-disallowable legislative instruments.[27]

This includes:

- subclause

22(1), which allows the Minister to establish a register of scheduling

decisions for industrial chemicals

- subclause

23(1), which proposes to enable the Minister to determine principles to be

complied with in making, varying or revoking scheduling decisions and

- clause

76, which enables the Minister to make rules prescribing various matters

required or permitted by the Bill, or which are necessary or convenient to be

prescribed for carrying out or giving effect to the Bill.[28]

The Scrutiny Committee observed that the note accompanying

each of these provisions states that section 42 (disallowance), and Part 4 of

Chapter 3 (sunsetting), of the Legislation Act

2003 do not apply to the instrument. The Committee expressed the view

that matters which may be significant to the operation of a legislative scheme

should be included in primary legislation unless sound justification for the

use of delegated legislation is provided.[29]

The Explanatory Memorandum does explain that the exemptions are because the

legislation facilitates the establishment or operation of an intergovernmental

scheme.[30]

However, the Committee stated its expectation that any exemption of delegated

legislation from the usual disallowance and sunsetting processes should be

fully justified in the Explanatory Memorandum, including why the exemption is

appropriate in the particular circumstances.[31]

As such, the Committee requested the Minister's advice as

to why it is appropriate and necessary for the relevant matters to be left to

the delegated legislation which is exempt from parliamentary disallowance and

sunsetting.[32]

The Committee also queried whether the Bill could be amended to provide that

these matters are subject to the usual parliamentary disallowance and

sunsetting processes.[33]

In response, the Minister advised that the exemptions in

sections 44 and 54 of the Legislation Act are ‘automatic exemptions’,

and:

… at the time of enactment, the rationale for including these

exemptions for instruments made under national schemes focused on concerns

about unilateral actions of one party to an agreement affecting the operation

of multi-jurisdictional schemes.[34]

In relation to the proposed principles, the Minister

explained that they would be included in a technical document based on up-to-date

scientific information and as such, ‘it is appropriate that the Principles be

set out in delegated legislation to allow for them to be amended as necessary

in response to evolving scientific knowledge’.[35]

The Minister gave similar reasons in relation to the Register and Rules.[36]

The Minister also explained, for example, that as the states and territories

will draw from the scheduling decisions in the Register, if the Register were

subject to sunsetting, certainty could be undermined for both governments and

industry, and disallowance ‘would affect the content of State and Territory

legislation, which would be inconsistent with the intergovernmental agreement.’[37]

The Committee noted the Minister's advice, but requested

that an ‘addendum to the explanatory memorandum containing the key information

provided by the minister be tabled in the Parliament as soon as practicable’.[38]

The Committee also drew its scrutiny concerns to the attention of Senators and

left to the Senate as a whole:

… the appropriateness of leaving matters which are

significant to the operation of the legislative scheme established by the Bill,

including principles to be complied with when making scheduling decisions and

rules prescribing a wide range of matters, to delegated legislation which is

exempt from parliamentary disallowance and sunsetting.[39]

Charges Bills

The Committee also raised concerns in relation to each of

the three Charges Bills, which seek to impose a charge as a tax payable by a

registered introducer of industrial chemicals for a registration year. The

Committee noted that subclause 8(1) of each Bill provides that the

amount of the charge payable in each case may be prescribed by the regulations,

and the regulations may either set out the amount of the charge payable or a

method for working out the amount.[40]

The Committee stated its ‘consistent scrutiny view’ that

‘it is for the Parliament, rather than makers of delegated legislation, to set

a rate of tax.’[41]

The Committee noted that the Explanatory Memoranda state that there is a need

for flexibility in prescribing the amount of the charge and that any applicable

charge will be determined through a Cost Recovery Implementation Statement and

will be consistent with the Australian Government Charging Framework and the

Australian Government Cost Recovery Guidelines.[42]

Nonetheless, the Committee noted that it ‘has generally not accepted a desire

for administrative flexibility to be a sufficient justification, of itself, for

leaving significant matters to delegated legislation’.[43]

The Committee suggested that it is unclear to ‘why at least high-level guidance

in relation to these matters cannot be provided’.[44]

The Committee therefore requested the Minister's advice as

to whether:

- guidance

could be specifically included in each Bill in relation to the method of

calculation of these charges and/or a maximum charge or

- the

Bills could be amended to specify that, before the Governor-General makes

regulations prescribing an amount of charge, the Minister must be satisfied

that the amount of the charge is set at a level that is designed to recover no

more than the Commonwealth’s likely costs in connection with the administration

of the framework established by the ICEMR Bill.[45]

In response, the Minister advised that the amount of any

applicable charge will be determined through a Cost Recovery Implementation

Statement (CRIS) and that this CRIS (including the method of calculation) would

be released for public consultation.[46]

The Minister advised that, for these reasons, the method of calculation of

charges or the maximum charge will not be able to be included in the Bills

themselves before this process is completed.[47]

The Minister further advised that the Department of Finance must be satisfied

that the charge is set at a level that is designed to recover no more than the

full and efficient costs of the administration of the framework and that the

Finance Minister must agree to the final CRIS.[48]

The Committee noted this advice, and requested ‘an

addendum to the Explanatory Memorandum containing the key information provided

by the minister be tabled in the Parliament as soon as practicable’.[49]

The Committee also drew this matter to the attention of senators and left to the

Senate as a whole the appropriateness of allowing the rate of charges in

relation to the scheduling of industrial chemicals to be set in delegated

legislation.[50]

Finally, the Committee also drew this matter to the attention of the Senate Standing

Committee for the Scrutiny of Delegated Legislation.[51]

Amendment Bill

The Scrutiny Committee had no comment on the Amendment

Bill.[52]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

At the time of writing, non-government parties and

independents do not appear to have commented on the Bills.

Position of

major interest groups

In its submission to the Senate inquiry, Accord[53]

supported the introduction of a new framework for a nationally uniform approach

for the environmental risk management of industrial chemicals.[54]

However, it highlighted the ‘regrettably poor timing’ of the introduction of

the regime during a time of pandemic, particularly given the industry concern

about costs and other administrative burdens associated with the proposed new

regime.[55]

Nonetheless, Accord supported the ICEMR Bill ‘being passed as written’.[56]

In its submission to the Senate inquiry, Chemistry

Australia supported the principles to which the Bills are directed, being the protection

of the environment through the appropriate management of risks posed by

industrial chemicals; and the establishment of nationally consistent,

transparent, predictable, streamlined and efficient approaches to the

environmental risk management of industrial chemicals. Chemistry Australia also

supported those elements of the Bills that provide a framework for Australia to

ratify and give effect to the decisions made under the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants and other international agreements.[57]

However, Chemistry Australia noted that the success of the

scheme and its ability to meet its objects is entirely dependent upon its

uniform adoption in state and territory legislation.[58]

Chemistry Australia expressed concern that, without uniform adoption:

… the scheme will simply introduce an additional layer of

regulatory burden/cost and potentially become an obstacle to the availability

of newer, innovative and safer chemistry in Australia, undermining all of the

benefits of the reforms introduced by the Industrial Chemicals Act 2019.[59]

For this reason, Chemistry Australia suggested a provision

be incorporated in the Bills to delay commencement of the scheme until

implementing legislation has been passed by every state and territory. Chemistry

Australia considered this would ‘encourage all states and territories to

promptly enact legislation to implement the scheme and avoid a situation under

which different rules might continue to apply across jurisdictions for some

time’.[60]

The Minerals Council of Australia did not make a

submission to the Senate Committee Bill inquiry but did make a submission in

relation to the exposure draft of the Bill (as mentioned in the ‘Background’

section of this Digest). In that submission, the Minerals Council expressed

general support for the draft Bill, particularly the requirements for the

Minister to consult before making, varying or revoking a scheduling decision on

an industrial chemical, and to comply with the decision-making principles.[61]

The Minerals Council also supported the ‘standing of the register’ as not

prohibiting, restricting or creating obligations in State or Territory

jurisdictions.[62]

The Minerals Council considered that ‘this approach allows for flexibility in

chemical management pending the activity and locality with respect to

environment and social considerations’.[63]

Cost recovery

Several industry groups expressed concern about the cost

recovery arrangements proposed for the new regime. For example, Accord

expressed concern about the increases in registration costs already experienced

as a result of the AICIS scheme, and about the limited transparency ‘at this

stage about the estimated costs’ relating to the proposed new regulatory scheme

to be established by the ICEMR Bill.[64]

Accord called for the charges to be set at nil initially, along with

‘meaningful consultation’ with industry on the cost‑recovery

arrangements.[65]

The Vinyl Council of Australia (the peak association for

the vinyl, or PVC, industry in Australia) similarly noted the intention that

annual scheduling charges on registered introducers of industrial chemicals

should be implemented on a government cost recovery basis. The Council raised

concerns about the impact of existing AICIS registration fees on its members,

and particularly small businesses, and suggested that the AICIS registration

fee schedule be amended.[66]

Chemistry Australia also noted the current fees and

charges imposed on industry under the AICIS, which it considered ‘already

incorporate elements of cost recovery for the environmental assessment of

industrial chemicals’.[67]

Chemistry Australia therefore questioned whether a separate cost recovery

scheme under the ICEMRB is necessary:

While the collection of the ICEMRB fee might be managed as

part of the annual AICIS fee payment arrangements, a separate cost recovery

scheme will still require additional work by the Department, including the

preparation of annual cost recovery impact statements and consultations with

stakeholders. It will also impose additional burdens on industry. The costs

associated with the cost recovery regime may well end up being a significant

part of the costs of administering the Register.[68]

On this issue, the Minerals Council suggested (in its

submission on the Exposure draft of the Bill) that cost recovery arrangements

should ‘focus primarily on new substances’, given that extensive data already

exists for a range of substances.[69]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the measures in

the ICEMR Bill ‘are estimated to have a minimal financial impact on the

Australian Government Budget’:

The initial costs of implementing the National Standard have

been funded by the measure ‘Environmental Management – the use and disposal of

industrial chemicals’ which provides $9.1m for 5 years from 2019/20 (and

$1.3 million per year ongoing) to set standards for how industrial chemicals

that pose a risk to the environment should be managed through their life cycle.

The Bill introduces arrangements to recover the cost of this measure through a

levy applied alongside the annual registration charge for chemical introducers

under the Industrial Chemicals Act 2019.[70]

The Charges and Amendment Bills have no financial impact

on the Australian Government.[71]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

compatibility of the Bills with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bills are compatible.[72]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had no

comment on the Bills.[73]

Key issues

and provisions[74]

Purpose of

the Bills

These Bills aim to build on the recent reforms to the

regulation of industrial chemicals by the Industrial Chemicals Act.[75] While industrial

chemicals are assessed for health and environmental risks through the AICIS

under the Industrial Chemicals Act, regulations for managing the

environmental risks of those chemicals vary across Australia. As the

Explanatory Memorandum states:

Under the current regulatory framework for environmental risk

management of industrial chemicals, there is no mechanism to consistently

implement the recommendations for the management of risks to the environment

made by AICIS … in contrast to other frameworks for worker and public health

and safety, such as the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and

Poisons (also known as the Poisons Standard).

Without a national approach, inconsistent implementation of

recommendations for managing the risks from the use of industrial chemicals may

lead to uncertainty, increased costs for business, and inadequate environmental

protection.[76]

The ICEMR Bill aims to address these issues and ‘fill an

important regulatory gap’ by establishing a new national standard for the

environmental risk management of industrial chemicals.[77]

As discussed earlier in this Digest, some stakeholders, such as Chemistry

Australia, have highlighted that whether the scheme meets its aims will depend

on adoption and implementation by state and territory governments.[78]

Chemistry Australia considered that without uniform adoption, there is a risk

that the scheme will introduce an additional layer of regulatory burden and

cost to industry.[79]

Objects

Clause 3 sets out the objects of the proposed ICEMR

Act as:

- to

give effect to an intergovernmental scheme involving the Commonwealth and the

states and territories relating to the establishment of nationally consistent

standards to minimise risks to the environment from industrial chemicals

- to

provide for the Commonwealth Government to establish a national register of

scheduling decisions for relevant industrial chemicals

- to

provide for the Register to operate as a national scheme, in that another law

of the Commonwealth, or a law of a state or territory:

- may

apply or adopt the Register (with or without modification) and

- may

make provision for, or in relation to, its implementation and enforcement, as

so applied or adopted

- to

reflect, through scheduling decisions for relevant industrial chemicals

included in the Register, the views of the Commonwealth on the controls,

including risk management measures, that should be applied to those chemicals

- to

regulate the conduct of the Commonwealth, and persons employed or engaged by

the Commonwealth, in connection with the Register

- to

contribute to meeting Australia’s international obligations in relation to

industrial chemicals.[80]

Key definitions

Clauses 7 and 8 provide definitions of key terms to

be used in the proposed Act. Some of the key definitions include ‘industrial

chemical’ and ‘industrial use’, which are defined by reference to their meaning

in the Industrial

Chemicals Act 2019.

Importantly, scheduling decisions under the proposed

regime will only be able to be made for industrial chemicals, which means that only

industrial chemicals will be included in the Industrial Chemicals Environmental

Management Register (which is discussed further below).

Industrial chemical

Section 10 of the Industrial Chemicals Act defines

an ‘industrial chemical’ as any of the following:

- a

chemical element that has an industrial use

- a

compound or complex of a chemical element that has an industrial use

- a

UVCB substance that has an industrial use[81]

- a

chemical released from an article where the article has an industrial use

- a

naturally-occurring chemical that has an industrial use

- any

other chemical or substance prescribed by the rules that has an industrial use

but not a chemical or substance that is prescribed by the

rules as not being an industrial chemical.

Industrial use

Subclause 8(2) clarifies that the proposed ICEMR

Act will only apply to an industrial chemical to the extent that the

industrial chemical is used, or proposed to be used, for an ‘industrial use’

within the meaning of the Industrial Chemicals Act. In other words, if

an industrial chemical has both industrial uses and non-industrial uses,

scheduling decisions will only be able to be made in respect of the industrial

uses (or proposed industrial uses) of that chemical.

The term ‘industrial use’ is defined in section 9 of the Industrial

Chemicals Act as a use other than (or in addition to) one of the

following uses:

- use

as an agricultural or a veterinary chemical product[82]

(within the meaning of the Agvet Code)

or in the preparation of such a product

- use

as a substance or mixture of substances[83]

(or in the preparation of such a substance or mixture of substances)

- use

as a therapeutic good (within the meaning of the Therapeutic Goods Act)

or in the preparation of such a good

- use

as food intended for consumption by humans (or in the preparation of such food)

- use

as feed intended for consumption by animals (or in the preparation of such feed)

- any

use prescribed by the rules.

Industrial Chemicals Environmental

Management Register

Clause 22 of the Bill provides for the

establishment of the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management Register

(the Register). Under subclause 22(1), the Register is established by

the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment by a non-disallowable legislative

instrument.[84]

The Explanatory Memorandum states that the Register is

exempt from disallowance and sunsetting because the enabling legislation for

the Register (that is, this Bill) facilitates the establishment or operation of

an intergovernmental scheme involving the Commonwealth and one or more states

and territories, and authorises the instrument to be made for the purposes of

the scheme.[85]

As outlined earlier in this Digest, the Scrutiny of Bills

Committee expressed concern that the Register will be set out in a non-disallowable

legislative instrument given the Register’s significance to the operation of

the proposed regime, and requested an explanation from the Minister in relation

to this issue.

Subclause 22(2) provides that the Register may

include explanatory information relating to the Register or a scheduling

decision, or any other information specified in the rules. The Explanatory

Memorandum suggests this might include additional information concerning an

industrial chemical or its use, descriptions of the Schedules, relevant

guidelines or management plans, or information to assist in the interpretation

and implementation of the risk management measures specified for a particular

industrial chemical.[86]

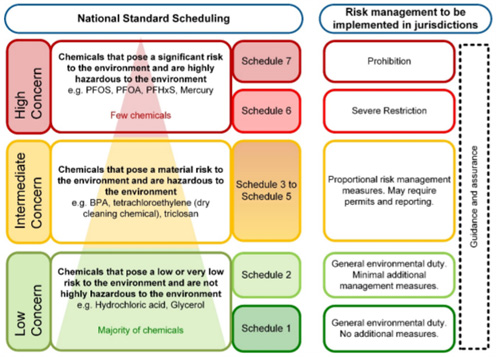

The Explanatory Memorandum anticipates that there will be

seven schedules of the Register, ‘reflecting increasing risk of harm to the

environment’ (see Figure 1 below).[87]

Figure 1: proposed structure of the

national standard

Source: DAWE, Submission

to the Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications, Inquiry

into the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management (Register) Bills 2020,

[Submission no. 2], 21 January 2021, p. 6.

The intention is that industrial chemicals will ‘be listed

by reference to a particular end use’, since ‘it will generally be the end use

of an industrial chemical that determines the level of concern that chemical

poses to the environment, and that has been assessed in a risk assessment’.[88]

As such:

Which Schedule is appropriate for a particular industrial

chemical or use of that chemical will depend on the risk characteristics of

that chemical. This would be determined by reference to both the inherent

characteristics of the chemical and its proposed use. This means that different

end uses of the same chemical could be listed in different Schedules of the

Register … because different end uses of an industrial chemical may have

different levels of environmental concern associated with them.[89]

Subclause 22(4) provides that the Registrar does

not, of itself, create prohibitions, restrictions or other obligations that are

enforceable in judicial or other proceedings. As the Explanatory Memorandum

notes:

… it is intended that each State and Territory (and the

Commonwealth) will, under their own laws, adopt or apply the Register and

thereby be responsible for implementing and enforcing the contents of the

scheduling decisions listed in the Register in their jurisdiction. In other

words, the prohibitions and restrictions that are listed in the Register for an

industrial chemical will not be enforceable except as they are adopted or

applied in the relevant jurisdiction.[90]

In turn:

It is intended that adoption of the Register by all

jurisdictions will deliver greater certainty and consistency in regulation for

industrial chemical users and introducers in Australia. It will also allow for

better protection of the environment through improved management of the

environmental risks posed by industrial chemicals.[91]

The Department’s submission to the Senate Committee

inquiry states that the ‘Australian Government is committed to implementing the

Register in areas of Commonwealth responsibility’.[92]

This will include developing ‘new legislation for the use, handling and

disposal of chemicals on Commonwealth land, as well as improving controls on

introduction of high concern chemicals into Australia’.[93]

As discussed in the ‘position of major interest groups’

section of this Digest, Chemistry Australia was concerned that the success of

the scheme is ‘entirely dependent’ on uniform adoption and implementation by

state and territory governments.[94]

Chemistry Australia recommended that a provision be incorporated to delay

commencement of the scheme until implementing legislation has been passed by

every state and territory. It suggested this would ‘encourage all states and

territories to promptly enact legislation to implement the scheme and avoid a

situation under which different rules might continue to apply across

jurisdictions for some time’.[95]

Scheduling decisions

Subclause 11(1) provides that the Minister may make

one or more scheduling decisions for a relevant industrial chemical.[96]

The Minister must ensure that the scheduling decision is recorded in the

Register (subclause 11(2)).

A ‘scheduling decision’ is defined in subclause 11(3)

as any of the following:

- a

decision to list the chemical in a particular Schedule or Schedules of the

Register

- a

decision to specify any one or more of the following for a chemical listed on

the Register:

- that

the export, import or manufacture of the chemical is prohibited, or restricted,

in all circumstances or in specified circumstances

- that

all or any end uses for the chemical are prohibited, or restricted, in all

circumstances or in specified circumstances

- one

or more end uses for the chemical

- one

or more risk management measures for the chemical or for a specified end use of

the chemical or

- a

decision relating to the chemical of a kind specified in the rules.

The Explanatory Memorandum states:

Industrial chemicals vary widely in their properties and the

ways in which they are used. It is therefore appropriate to have a selection of

management options available to the Minister in making a scheduling decision.

Listing a chemical or end use of a chemical in a Schedule of the Register will

indicate the level of concern it poses to the environment. In many cases, few

or no risk management measures will be necessary to manage the risks posed by a

particular chemical. In some cases, it will be possible to manage the risks

posed by certain end uses of a chemical, but not others. When there are

significant risks posed by a particular chemical, regardless of end use, and it

is not possible to manage those risks, it may be necessary to ban all end uses

of the chemical, as well as its import and manufacture. In some instances, such

as to comply with Australia’s international obligations, it may also be

necessary to ban the export of certain chemicals.[97]

The Minister may list an industrial chemical in a Schedule

of the Register even if it is already included in a class of industrial

chemicals listed in that Schedule or a different Schedule of the Register.[98]

The Explanatory Memorandum states ‘this is to ensure that chemicals can be

listed in different Schedules (or the same Schedule) of the Register at the

same time by reference to different end uses of that chemical’.[99]

Subclause 11(6) aims to clarify the scope of a risk

management measure that can be specified by the Minister in a scheduling

decision. A risk management measure may:

- prohibit

or restrict particular conduct or things in all circumstances or in specified

circumstances

- require

particular conduct or things in all circumstances or in specified circumstances

- impose

an obligation in relation to particular conduct or things in all circumstances

or in specified circumstances or

- apply

from or until a particular date or for a particular period.

As the Explanatory Memorandum notes:

Risk management measures aim to prevent harm to the

environment from the use or disposal of an industrial chemical. For example,

risk management measures may relate to the protection of land or the marine

environment, the protection of surface or ground water, the protection of

biodiversity, the storage, handling and containment of the chemical, or the

treatment or disposal of the chemical.[100]

The Minister may also vary or revoke a scheduling decision

for a relevant industrial chemical. That variation or revocation must be

recorded in the Register.[101]

Considerations for scheduling

decisions

Clause 15 sets out the mandatory considerations for

the Minister when deciding whether to make, vary or revoke a scheduling

decision. The Minister must have regard to the following matters:

- the

most recent relevant Commonwealth risk assessment[102]

for the industrial chemical (if any)

- any

relevant risks that the chemical, or end use of the chemical, poses (or may pose)

to the environment and how any such risks may be minimised

- any

relevant advice given to the Minister by the Advisory Committee

- any

relevant international obligations Australia has under an international agreement

that is specified in the rules[103]

- any

relevant submissions provided as part of public consultation on the proposed scheduling

decision and any relevant information given to the Minister under clauses 19 or

20 (discussed below) and

- any

other matters that are specified in the rules.

These mandatory considerations do not apply to a variation

of a scheduling decision that is of a ‘minor nature’ (subclause 15(2)). Subclauses

15(3) and (4) provide that the following are taken to be variations

of a minor nature:

- a

variation that does no more than change the way the chemical is identified and

- a

variation that specifies an end use for a chemical instead of a generalised end

use.

The discretionary matters that the Minister may have

regard to when deciding whether to make, vary or revoke a scheduling decision

are set out in clause 16 as follows:

- earlier

Commonwealth risk assessments in relation to the chemical[104]

- a

risk assessment in relation to the chemical undertaken by a Commonwealth entity

(but that does not fall within the definition of Commonwealth risk assessment

in clause 7)

- a

risk assessment in relation to the chemical undertaken by a state or territory

government body, a foreign government body or a public international

organisation

- any

environmental, social or economic matter that the Minister considers relevant

- any

relevant information given to the Minister by an ‘entrusted IC person’[105]

and

- any

other matters that are specified in the rules or that the Minister considers

relevant.

Decision-making principles

Clause 13 requires the Minister to comply with the decision-making principles when making, varying or

revoking a scheduling decision and provides that the Minister cannot make a

scheduling decision unless the decision-making principles are in force. The

Minister may make, vary or revoke these decision‑making principles by

legislative instrument under clause 23. The Department’s submission to

the Senate Committee inquiry further explains:

The Principles will set out criteria for deciding which

Schedule of the Register an industrial chemical (or particular use of an

industrial chemical) should be assigned to, according to its level of concern

to the environment. These criteria are called risk characteristics.[106]

According to the Department, the principles are expected

to be made ‘shortly after passage of the Bill’.[107]

Draft

principles have already been published on the Department’s website.[108]

Clause 24 also requires a mandatory 20 business day public consultation

period before the Minister makes, varies or revokes the principles. Clause

25 requires the Minister to consult with state and territory Environment

Ministers before making, varying or revoking the decision-making principles.[109]

The notes to subclauses 23(1) and (2) of the

Bill state that the decision-making principles will be exempt from disallowance

and sunsetting provisions of the Legislation Act

2003. The Department’s submission to the Senate Committee inquiry

explains:

The Principles represent a key component of the National

Standard and will be developed in collaboration with the states and

territories, and consultation with stakeholders. Were they to be subject to

disallowance or sunsetting, the collaborative interjurisdictional effort that

went into the development of the National Standard could be undermined. Subsections

44(1) and 54(1) of the Legislation Act ensure the integrity of these

interjurisdictional schemes is maintained.[110]

However, as outlined earlier in this Digest, the Scrutiny

of Bills Committee expressed concern that the principles will be set out in non-disallowable

legislative instrument, particularly given their significance to the operation

of the proposed regime.

Public consultation before

scheduling decisions

Clause 17 requires the Minister to undertake public

consultation before making, varying or revoking a scheduling decision. The

Minister must publish a notice on the Environment Department’s website inviting

submissions on the proposed scheduling decision (or the proposed variation or

revocation). The timeframe to provide submissions to the Minister must be no

less than 20 business days.[111]

Under subclause 17(3), public consultation is not

required for a minor variation of a scheduling decision. Subclauses 17(4)

and (5) provide that the following are taken to be minor variations:

- a

variation that does no more than change the way the chemical is identified and

- a

variation that specifies an end use for a chemical instead of a generalised end

use.

The Explanatory Memorandum suggests this would, for

example, allow variations to correct a typographical error or substitute the

proper name of the chemical without having to undertake public consultation

again:

This is considered appropriate because such variations would

not affect the substance of the original scheduling decision.[112]

Clause 18 provides an exception to this public

consultation requirement if an assessment certificate has been issued in

relation to a particular industrial chemical, although the Minister may still

consult the holder of the assessment certificate and the public if appropriate.[113]

Assessment certificates are issued under Industrial Chemicals Act:[114]

An assessment certificate issued under the Industrial

Chemicals Act 2019 relates to the proposed introduction to Australia (by

import or manufacture) of a new industrial chemical or a new use of an

industrial chemical. The proposed new chemical or use will have already been

the subject of consultation under that Act and further public consultation will

not generally be considered useful. A newly introduced chemical or use may also

be the subject of confidential business information protections, making public

consultation inappropriate. However, targeted consultation with the holder of

the assessment certificate (the proposed introducer) may still be considered

appropriate or necessary in the particular circumstances.[115]

Under clause 19, the Minister may, by written

notice, request information that is relevant to a scheduling decision from a

specific person, such as the introducer of an industrial chemical, a relevant

industry body, a Commonwealth body or Department or an independent expert.[116]

Clause 20 also provides a mechanism for the

Minister to make a public call for information, via the Environment Department’s

website, relevant to the making, varying or revoking of a scheduling decision.

As the Explanatory Memorandum notes, clauses 19 and 20

are not intended to be coercive powers, and the Minister would not be able to

compel a person to provide information in response to a request or invitation

made under subclauses 19(1) and 20(1).[117]

Under clause 21, the Commonwealth Minister may (but

is not required to) consult with state or territory environment ministers before

making, varying or revoking a scheduling decision.

Advisory Committee

Clause 27 in Part 3 of the ICEMR Bill establishes

the Advisory Committee on the Environmental Management of Industrial Chemicals

to provide independent expert advice to the Minister.[118]

Clause 28 provides that the Advisory Committee’s

functions include advising the Minister about matters that are referred to it

by the Minister and that relate to the making, variation or revocation of a

scheduling decision for a relevant industrial chemical, the Register or the

decision‑making principles. Other functions can be conferred on the

Advisory Committee by the rules made under clause 76 (as discussed later

in this Digest).

Clause 29 provides that the Advisory Committee

consists of a Chair and at least three, but not more than eight, other members.

Advisory Committee members are appointed by the Minister under clause 30.

A person is not eligible to be appointed as an Advisory Committee member unless

the Minister is satisfied that the person has substantial experience or

knowledge, and significant standing, in certain fields as specified in

subclause 30(3), such as industrial chemistry, ecotoxicology, environmental

risk management, environmental health, human toxicology, applied socio-economic

analysis, ecology, or chemical or environmental regulation.

Rules

Clause 76 in Part 6 of the ICEMR Bill enables the

Minister to make rules prescribing matters to support the proposed ICEMR Act.

Several clauses in the Bill provide for matters to be prescribed in the rules

including:

- other

risk assessments that will be characterised as Commonwealth risk assessments (under

the definition of Commonwealth risk assessment in clause 7)

- international

agreements under which Australia has obligations in relation to industrial

chemicals. The Minister must have regard to any international agreement

prescribed in the rules when making, varying or revoking a scheduling decision

(clause 15)

- other

matters the Minister must or may have regard to when making, varying or

revoking a scheduling decision (clauses 15 and 16)

- additional

functions of the Advisory Committee (clause 28) or the AICIS Executive

Director (clause 72) and

- matters

relating to collecting and recovering the scheduling charge (clause 69).

The rules would be a legislative instrument for the

purposes of the Legislation Act, but would not be disallowable or

subject to sunsetting.[119]

The Explanatory Memorandum states:

This is because the enabling legislation for the rules (being

this Bill) facilitates the establishment or operation of an intergovernmental

scheme involving the Commonwealth and one or more states, and authorises the

instrument to be made for the purposes of the scheme.[120]

As outlined earlier in this Digest, the Senate Scrutiny of

Bills Committee raised concerns that this means that significant matters

relating to the operation of the regime are being left to delegated legislation

which is exempt from parliamentary disallowance and sunsetting.

Cost recovery

The ICEMR Bill, along with the Charges Bills, establish

cost recovery arrangements for the proposed scheme. Part 5 of the ICEMR Bill sets

out provisions relating to the scheduling charge, including who is liable for

the charge (clause 67), when the charge is due for payment (clause 68)

and enabling rules to be made for the collection and recovery of the charge (clause

69).

Clause 67 provides that that a registered

introducer for a registration year would be liable to pay the scheduling

charge. A registered introducer for a registration year means a person

registered under section 17 of the Industrial Chemicals Act.[121]

As the Explanatory Memorandum states:

In practice, this will mean that a person who is liable under

the Industrial Chemicals Act 2019 to pay a registration charge in

respect of the introduction of a new industrial chemical (or a new use of an

existing industrial chemical) would also be liable to pay a scheduling charge

under this Bill. This is appropriate as it recognises that there will be no

separate application to assess a new industrial chemical (or a new use of an

existing industrial chemical) under the Bill for the purposes of making a

scheduling decision. Rather, it is intended that an application for

registration of a new industrial chemical (or a new use of an existing

industrial chemical) under the Industrial Chemicals Act 2019 will be a

trigger for the Minister to assess the environmental risks of the proposed

chemical or use for the purposes of making one or more scheduling decisions

under the Bill.[122]

The scheduling charge is then imposed under the Charges

Bills.[123]

The Charges Bills enable the amount of charge payable to be prescribed in

regulations.[124]

The definition of ‘amount’ enables the charge to be nil.[125]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the ICEMR Bill states:

Consistent with the Australian Government Charging Framework,

the amount of the scheduling charge imposed under the relevant charges Bills

would be determined through a Cost Recovery Implementation Statement. The

amount will also be required to recover no more than the Commonwealth’s likely

costs and, as such, will be limited in amount to the approximate cost of services

rendered by the Commonwealth.[126]

As discussed earlier in this Digest, the Senate Scrutiny

of Bills Committee raised some concerns in relation to the Charges Bills.

Similarly, as noted in the ‘position of major interest groups’ section earlier

in this Digest, several industry groups raised concerns about the proposed cost

recovery arrangements. However, law firm Clayton Utz has suggested that, ‘while

adapting to the new scheme may require up‑front costs to a business, the

single national register is intended to lead to significant reductions in

compliance costs in the long term’.[127]

Confidentiality and information

sharing

Part 4 of the ICEMR Bill contains provisions dealing with

confidential information, the use and disclosure of protected information and

other information sharing matters. These provisions are adequately explained in

the Explanatory Memorandum to the ICEMR Bill. According to the Department’s

submission to the Senate Committee inquiry:

These provisions allow the Minister to decide whether to

publicly release information based on a weighing of the commercial interests of

companies in keeping specific information confidential against the public

interest in information being made available. The Bill also ensures that

companies are consulted on proposed decisions to release information and have

rights to reconsideration and review of decisions.[128]