Key issue

The iconic Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is a World Heritage site, a national heritage place and an area of tremendous cultural significance for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The GBR also has an estimated economic value of $56 billion and the industries associated with the ecosystem employ over 60,000 people.

The latest Outlook report, from 2019, found that the GBR ecosystem and its heritage values had deteriorated and were projected to deteriorate further without effective action. The main factors influencing the GBR’s values are climate change, land-based run-off, coastal development and direct use.

In 2021, the World Heritage Committee decided against placing the GBR on the List of World Heritage in Danger, although the possibility is likely to arise again. Both major and minor parties, as well as some independents have promised increased action on the GBR including through addressing climate change and improving water quality.

The significance of the Great Barrier Reef

The Great

Barrier Reef (GBR) covers an area of over 340,000 km2 and is the world’s largest coral

reef system. The GBR is comprised of some

3,000 coral reefs and is roughly the same size as Italy or Japan. It stretches

2,300 km along the Queensland coastline from north of K'gari (Fraser Island) in

the south, to the tropical waters of the Torres Strait.

Ecologically rich, the GBR is home to more than 600

different types of soft and hard corals, 1,625 types of fish and more than 30

species of whales and dolphins. The 1,050

individual islands and cays provide important breeding and roosting

habitat, feeding grounds and migratory pathways for at least 23 seabird and 32 shorebird species (p. 4).

The GBR itself, plus its associated islands and

intertidal areas of coastal state waters are made up of a huge variety of

marine habitats including coral reefs, seagrass shoals, mangroves, algal beds

and sponge gardens. Since 2004, management of the GBR has

been based on the recognition that each of these habitats plays a critical

role in supporting the overall health and functioning of the GBR ecosystem.

Although separately classified, the

30 defined bioregions of reef habitat and 40 bioregions of non-reef habitat within the GBR are inextricably interconnected.

The GBR is also of tremendous cultural and spiritual significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There

are some 70 Aboriginal Traditional Owner groups with

authority for Sea Country management. Torres Strait Island Traditional Owner

groups are also connected to the GBR and hold cultural knowledge of the broader

GBR region. There are several Native Title claims along the Queensland

coastline as well as dedicated Indigenous Protected Areas.

At the global scale, the GBR is an iconic and instantly recognisable

location. Under the World Heritage Convention, the GBR is recognised for

its ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ (see further below) and attracts more than 2 million tourists each year.

Economically, the GBR supports over 60,000 jobs (mostly in the tourism

sector) with an estimated total ‘economic, social and icon asset value’ of $56 billion (p. 5).

The current state of the GBR

The most recent Scientific

consensus statement on land use impacts on GBR water quality and ecosystem

condition shows that the GBR is an ecosystem under pressure. Every five

years, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) prepares an Outlook

Report. The latest report,

released in October 2019, indicated the GBR’s continued deterioration. Collectively,

the GBR’s ecosystem was assessed as being in ‘very poor’ condition and its

heritage values in ‘poor’ condition (p. 270). The next Outlook report is

expected in 2024.

In November 2020, the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature (IUCN), in its World

Heritage outlook 3, described the outlook for the GBR as ‘critical’, noting

that the GBR had deteriorated since its previous report in 2017 (p. 22).

The GBR’s greatest threat is widely acknowledged to

be climate

change, which impacts the GBR through marine heatwaves, ocean

acidification, rising sea levels and increased frequency of damaging cyclones. Other

threats identified in the 2019 Outlook report and Reef

2050 long-term sustainability plan (Reef 2050 Plan) are:

- run-off of sediment, nutrients and other pollutants from land-based

activities

- coastal development

- direct human use (for example, illegal fishing and bycatch)

- marine

debris (such as microplastics, foam, rubber, glass and metal rubbish)

- spills (for example, chemical or oil spills)

- grounding vessels and damage to reef structure.

Accordingly, the GBR faces a raft

of cumulative pressures that will continue to test its resilience.

Coral bleaching and the GBR ecosystem

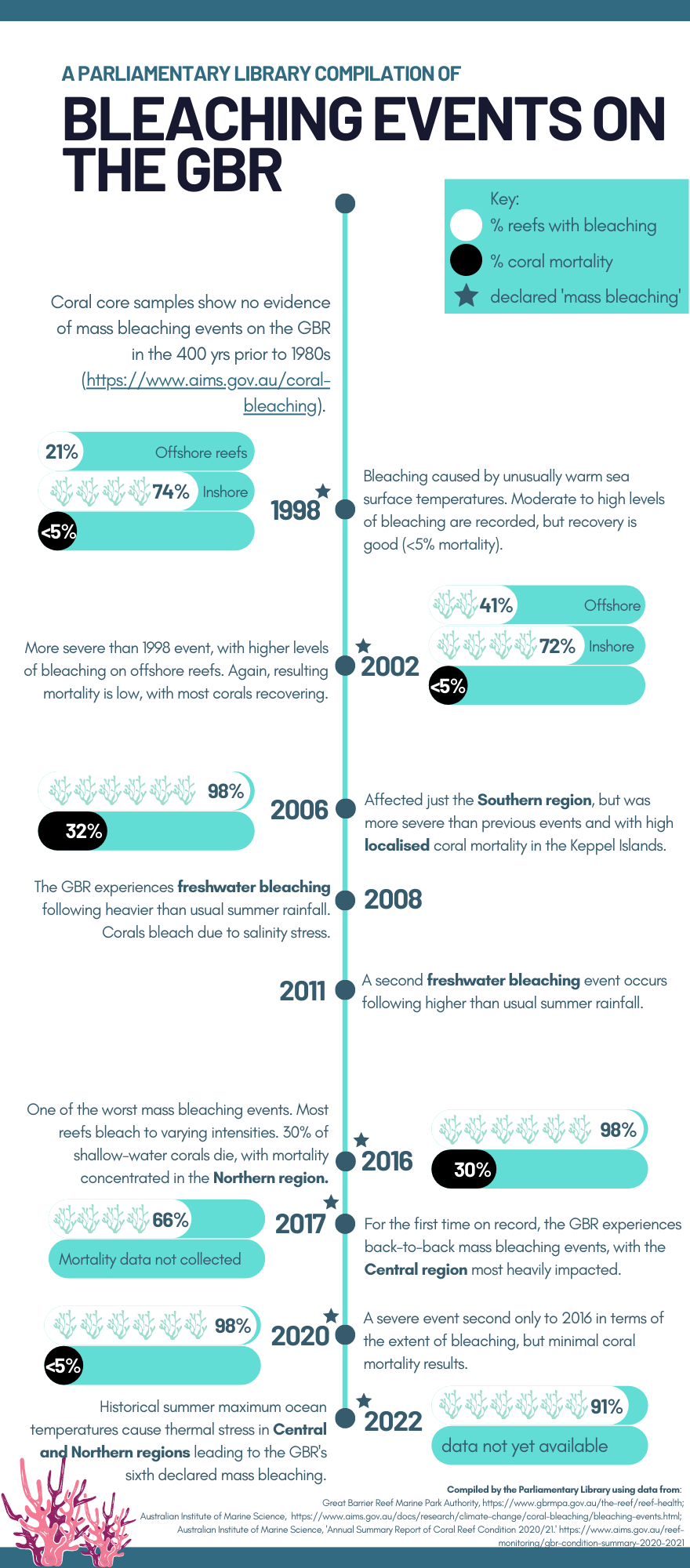

The effect of marine heatwaves on the health of

coral within the GBR has been particularly marked. These heatwaves cause coral

to become stressed, a phenomenon

known as bleaching. If the temperature anomaly continues for long enough,

the coral will gradually starve to death. These bleaching events are becoming

increasingly frequent (Figure 1), posing a threat to the GBR as coral both

builds the habitat and defines the entire ecosystem, so without it, the

ecosystem can no longer exist. When coral is lost, the reef ecosystem undergoes

an irreversible phase shift into an

alternative, degraded state. The alternative state cannot produce the same

products and services that the system once did and key biological and chemical

interactions with neighbouring habitats, such as mangroves and seagrass beds, are

lost. The preservation of coral reef habitat is therefore intrinsic to the

health and functioning of the wider GBR ecosystem as a whole.

The Australian Institute of Marine Science has monitored

bleaching events since the early 1980s. Severe coral bleaching took

place in 2016 and 2017 and most recently in the

summer of 2022. This was the fourth mass bleaching

event since 2016 and the sixth to occur since 1998 (Figure 1). This 2022 event

notably occurred during a La Niña year, typically associated with greater cloud

cover and cooler ocean temperatures.

Figure 1 A history of bleaching events

impacting the GBR

Inter-governmental cooperation

The need for federal-state collaboration on the GBR

has been recognised for some time. In 1979, the Queensland and Australian

governments signed the Emerald

Agreement to more effectively cooperate in reef management. The agreement

was updated

in 2009 and 2015.

The division of roles and responsibilities for the

protection of the GBR can be summarised as:

-

The Queensland Government has primary

responsibility for managing the (terrestrial) GBR catchment under its planning and environmental laws. The Commonwealth Government provides

additional assessments and approvals for major developments (ports,

dredging, coastal hotel development, etc) under the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC

Act).

- The Commonwealth Government, through GBRMPA, manages

the 344,400km2 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Federal Marine Park) in

accordance with its zoning

plan. The plan sets out which activities, such as fishing and boating, are permitted

in particular zones.

- The Queensland Government is responsible for managing

the 63,000km2 Great

Barrier Reef Coast Marine Park (Queensland Marine Park) in accordance with

its zoning

plan that covers

tidal lands and tidal waters.

-

The Queensland Marine Park and Federal Marine

Park overlap at the coastline, and, together with islands under the

jurisdiction of Queensland, comprise the GBR World

Heritage area. The Federal Marine Park makes up 99%

of the World Heritage Area.

-

The Queensland and Commonwealth governments have

fisheries responsibilities under the Fisheries

Management Act 1991 (Cth), Fisheries

Act 1994 (Qld) and EPBC Act.

- In terms of day-to-day operations, a joint

field management program exists between the Queensland and

Commonwealth governments.

The World Heritage Convention and the possibility

of an ‘in danger listing’

As a signatory to the World

Heritage Convention, Australia is committed to protecting the

‘Outstanding Universal Value’

(OUV) of World Heritage-listed sites like the GBR. Amongst other things, Australia

is obliged to:

[endeavour, insofar as possible and as

appropriate] … to take the appropriate legal, scientific, technical,

administrative and financial measures necessary for the identification,

protection, conservation, presentation and rehabilitation [of its World

Heritage sites] (Article 5(d)).

Australia has responded to its obligations under the convention

through policy initiatives and legislated environmental impact assessment and

approval provisions under the EPBC Act.

Within the World Heritage Convention, a 21-member World Heritage Committee makes decisions about listed sites, including those included on

the List of World Heritage in

Danger. Since 2011, the committee has consistently requested Australia take

stronger action to protect the GBR’s OUV (see Table 1).

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage

Centre is the committee’s secretariat and the IUCN is the official

advisory body for natural sites like the GBR. While the World Heritage Centre

and the IUCN work together to make recommendations for action, the committee

ultimately makes the decisions.

Table 1 Summary of World Heritage

Committee decisions relating to the GBR (2011–2021)

| Year |

World

Heritage Committee decision |

| 2011 |

- Noted with extreme concern the approval

of Liquefied Natural Gas processing and port facilities on Curtis Island,

Queensland.

- Urged Australia to undertake a strategic

assessment and invite a monitoring mission from IUCN/UNESCO.The mission subsequently took place

6 - 14 March 2012.

|

| 2012 |

- Noted the unprecedented scale of coastal

development currently being proposed within and affecting the property.

-

Requested completion

of a strategic assessment and resultant long-term plan.

- Considered

possible inscription on List of World Heritage in Danger in the

absence of progress.

|

| 2013 |

- Welcomed the progress on the strategic assessment

and long-term plan.

- Urged Australia to ensure no development

permitted if it would impact

individually or cumulatively on the OUV of the GBR, or compromise the strategic

assessment and resulting long-term plan.

- In the

absence of progress, suggested possible inscription on List of World

Heritage in Danger.

|

| 2014 |

-

Welcomed progress on

the strategic assessment and endorsement of the 2013 Reef Water

Quality Protection Plan.

-

Noted with concern recent approvals for coastal

developments, including the dumping of 3 million cubic metres of dredged

material.

- Considered

possible inscription on List of World Heritage in Danger in the

absence of further action.

|

| 2015 |

- Noted findings of GBRMPA’s 2014 Outlook

Report about the GBR’s deterioration and that

climate change, poor water quality and impacts from coastal development were major

threats.

- Welcomed Australia’s

efforts to create the Reef 2050 (long

term) Plan and its commitment to establish a permanent ban on dumping of

dredged material.

|

| 2017 |

- Welcomed the progress on the

implementation of Reef 2050 Plan.

- Requested that Australia accelerate

efforts to ensure meeting targets in relation to water quality entering the

GBR from land-based run-off.

|

| 2021 |

- Commended Australia on efforts to

implement the Reef 2050 Plan, although noted that water quality targets were not

met.

- Decided against including the GBR on the

List of World Heritage in Danger (although the IUCN and the World Heritage Centre had

recommended inclusion).

- Noted that climate change is the biggest

threat to the GBR and requests Australia invite a monitoring mission to

examine the Reef 2050 Plan (which had been revised in 2018).

- Requested Australia submit a report on

the State of Conservation of the GBR by 1 February 2022.

|

Source: UNESCO World Heritage Convention, Great Barrier

Reef, Documents.

In accordance with the 2021 committee decision, the

Australian Government submitted a report on the

state of conservation of the GBR. The report acknowledged that climate

change is the biggest threat facing the GBR but argued that the OUV of the site

remained intact. In the context of ’addressing the impacts of a changing

climate’, and the possibility of an In Danger Listing, the report sought to

delineate between threats it could and could not control:

While the List of World Heritage in Danger

remains a relevant and important tool where corrective measures can be

undertaken by individual States Parties to address threats to their World

Heritage properties that they can control, it is less instructive where the

ongoing impacts of a threat are beyond the control of any individual State

Party to address, and where changes to the OUV of a property as a result of

climate change will continue for many decades. For climate-impacted properties

there may be no prospect of removal from the List regardless of the level of

investment or the extent of the program of corrective measures implemented by

any individual State Party (p. 33).

The IUCN and the World Heritage Centre undertook a monitoring

mission to Australia

from 21–30 March 2022 but have not yet reported their findings. The

Committee is likely to consider these findings at its next meeting and may

again consider inclusion of the GBR on the In Danger List.

In accordance with the Operational guidelines for

implementation of the convention consideration of an In Danger

Listing will result in:

- the joint development by the Committee and Australia of a Desired

State of Conservation for the Removal (DSOCR) of the GBR from the In Danger

List

- a program of corrective measures to help restore the site’s OUV

(para 183).

If the

GBR is inscribed on the In Danger List, this would establish a cycle of annual

review and possible further monitoring missions by the World Heritage Centre and

the IUCN. Based on this information, the committee will then decide to either

retain or remove the GBR from the In Danger List, or, in the most extreme case,

to delete it altogether from the World Heritage List. The latter occurs only if

the committee determines a property has deteriorated to the point that it has

lost the OUV for which it was first inscribed. In the 50-year history of the

convention, this has only occurred for 3 sites: Arabian Oryx Sanctuary (Oman) in

2007, Dresden Elbe Valley

(Germany) in 2009 and Liverpool

Maritime Mercantile City (United Kingdom) in 2021.[1]

If the

GBR is listed In Danger, the designation could remain for many years, as is the

case with the US Everglades

National Park which faces similar water quality and climate change issues.

Funding, planning and ongoing reporting

Since 2014, the GBR and its terrestrial

catchments are reported to have received an ‘unprecedented’

level of investment (p. iv). In 2014–2015, the Reef Trust commenced and is now administered by

the Commonwealth Environment Department. The Reef Trust is primarily government-funded but can also receive offset funding (from

developments), as well as philanthropic and private contributions.

As part of its 2022–23 Budget, the Coalition Government announced

a 9-year $1 billion investment in GBR management and protection, across 4 key areas. During its election campaign, the ALP promised an

additional $194.5 million over the forward estimates on top of existing

programs for the same purposes. The Greens

presented a $2 billion plan that included grants to improve farming

practices to address land-based run-off. Several independent parliamentarians

and candidates have also called for stronger action on climate change.

At the state level, in June 2021 the Queensland

Government announced close

to $330 million for GBR-related programs, creating a cumulative total estimated

investment of more than $700 million since 2015. In March 2022, the Queensland

Government further announced that $65 million (of

the $270 million for Reef Water Quality Improvement programs) would be allocated

to catchment and waterways to tackle water pollution.

The Reef 2050 water

quality improvement plan 2017–2022 (RWQP) is the Queensland and Australian

Government’s key approach to improving water quality. The RWQP’s main focus is reducing

nutrient and chemical run-off from agricultural activities (grazing and

sugarcane in particular), but also targets pollution from urban, industrial and

public lands.

Annual Reef

water quality report cards measure progress towards the RWQP’s water

quality targets. The 2020

report card (released on 8 April 2022) details

progress up to June 2020 and, amongst other things, concluded:

According to the modelling we are more

than halfway to the sediment target and almost halfway to the dissolved

inorganic nitrogen target. Reductions are mostly due to improved nitrogen

fertiliser management and mill mud application in the sugarcane industry and

significant investment in fencing to exclude cattle from waterways (p. x).

The RWQP is ‘nested’ within the Reef 2050 plan,

which is the overarching GBR management strategy. The Reef 2050 plan was

developed following Australia’s largest ever Strategic

Environmental Assessment in 2012–2014 (see Table 1). Annual

reports under the Reef 2050 plan continue to track the progress of its

implementation.

Further reading

Australian Government and Queensland Government, Reef 2050 Water Quality Improvement Plan ‘Report Cards'-, 2022.

Australian Government and Queensland Government, Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan 2021-25-, 2021.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019 (Townsville: GBRMPA, 2019).

UNESCO, World Heritage Convention, Great Barrier Reef Documents.