In 2021, the Australian Medical Association reported that according to doctors, access to public hospitals was the worst it had been in 30 years (p. 10). Recent media coverage of patients being treated in corridors, ambulance ramping occurring in every state and territory, and bed and staff shortages around the country indicate that access issues have continued.

On 17 June 2022, the Prime Minister announced a review of health funding and health arrangements. This followed calls for months from state and territory leaders for the Commonwealth to increase its share of hospital funding, and concerns from peak bodies about the public hospital system being close to breaking-point.

This article outlines how the current system of hospital funding works and how much governments spend currently on public hospitals.

How are public hospitals funded?

The 2011 National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA) and its 2017 and 2020 addendums set out the division of responsibilities and funding between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments for the health system. Of note, the 2011 NHRA emphasises ‘the Commonwealth’s lead role in funding and delivering GP and primary health care and aged care’, and states that the Commonwealth Government ‘will work in partnership with the States to enable patients to receive the care they need when and where they need it’ to take ‘pressure off public hospitals’ (p. 6).

Public hospitals are co-funded by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments (with public hospitals also receiving money from private health insurers and individuals for private patients). The Commonwealth provides three types of funding for public hospitals (in addition to capital works funding):

- Activity Based Funding (ABF), which is based on the number and mix of patients a hospital treats, with the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority setting the price and the weight for each service type

- Block funding for certain public hospital services, particularly smaller rural and regional hospitals

- Public health funding aimed at improving overall health and preventing poor health, such as youth health services and essential vaccines.

Through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), the Commonwealth Government also pays 75% of Medicare Schedule fees for procedures rendered to private patients treated in public hospitals.

The Commonwealth and the states and territories pool funding for public hospitals through the National Health Funding Pool. These payments are not made directly to individual hospitals; rather they are pooled and then distributed to Local Hospital Networks, third parties on behalf of local hospital networks, state health departments and other providers.

States have flexibility to determine the amount they pay for public hospital services and how they make allocations to individual Local Hospital Networks.

The states and territories are responsible for employing and administering the hospital workforce, including staff remuneration.

How much do governments spend on hospitals?

Under the national overarching NHRA, overall growth in Commonwealth funding for public hospitals is capped at 6.5 % per year, with the states and territories to meet the balance of the cost of delivering public hospital services and functions (p. 23). Under the National Partnership on COVID-19 Response, since 21 January 2020, the Commonwealth has provided a 50% contribution for costs incurred by states and territories for the diagnosis and treatment of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases and activities to prevent the virus from spreading (p. 5). This Partnership Agreement is due to expire at the end of 2022.

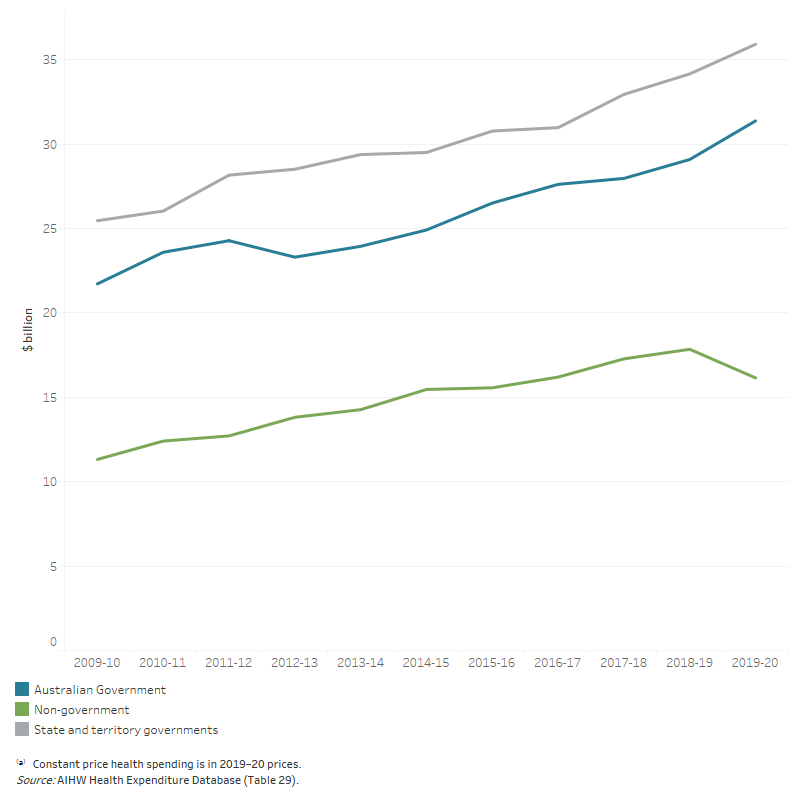

In 2019–20, the most recent year for which complete expenditure is available:

- state and territory governments contributed $34.9 billion (52.5%) to hospital funding

- the Commonwealth Government spent $29 billion (42.3%) if including spending for MBS items and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS)) or $26.8 billion (40.4%) if not

- non-government entities spent $4.7 billion (7%, which includes private health insurers and private patients paying gap fees) on public hospitals.

Figure 1 outlines increases in spending on public hospitals by source of funds from 2009–10 to 2019–20.

Figure 1: Public hospital spending, by source of funds, constant prices (2019–20 prices), 2009–10 to 2019–20

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Health Expenditure Australia 2019–20, 17 December 2021.

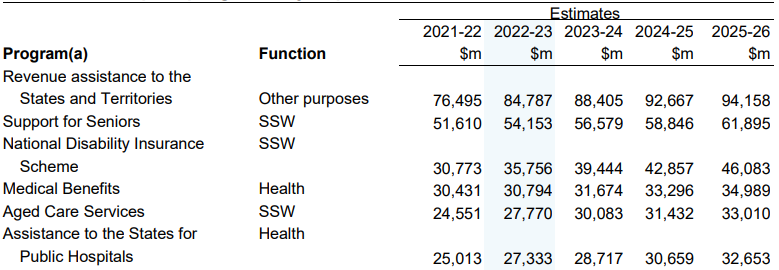

Under the Morrison Government’s 2022–23 Budget, assistance to the states and territories for public hospitals was estimated to be the sixth most expensive program in 2022–23 (p. 144), with spending in this category projected to reach $32.7 billion by 2025–26 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Top programs by expenses in 2022–23

(a) The entry for each program includes eliminations for inter-agency transactions within that program

Source: Australian Government, Statement 5: Expenses and Net Capital Investment, Budget 2022–23: Budget Paper No. 1, p. 144.

When looking at areas of expenditure specifically for health, spending by all sources on hospitals has increased proportionally since 2016–17. Spending on primary healthcare has proportionally decreased.

Areas that impact demand for public hospitals

Demand for public hospitals, and strain on the existing system, is caused by multiple factors, including:

Where to from here?

Despite pressure from the states and the sector, the Federal Health Minister has announced that the Commonwealth will not increase its share of hospital funding under the current NHRA, which will expire in 2025. Recent Commonwealth measures flagged to reduce strain on hospitals include increased investment in preventative health and primary care, particularly for more out-of-hours GPs. The NHRA also includes key areas of reform, including prevention and wellbeing, and a Roadmap for governments to follow to implement these reforms. It remains to be seen what other measures the Government review will propose.