While New Zealand participated in the Australasian Federation Conference convened in Melbourne in 1890, it had little real enthusiasm for the prospect of federating with the Australian colonies. As Sir John Hall, then Premier of New Zealand and one of two New Zealand delegates to the Conference, observed:

Nature has made 1200 impediments to the inclusion of New Zealand in any such Federation in the 1,200 miles of stormy ocean which lie between us and our brethren in Australia.That does not prevent the existence of a community of interests between us. There is a community of interest, and if circumstances allow us at a future date to join in the federation, we shall be only too glad to do so. But what is the meaning of having 1,200 miles of ocean between us? Democratic government must be a government not only for the people, and by the people, but, if it is to be efficient; and give content, it must be in sight and within hearing of the people.

Beyond sheer distance, other issues in play were ‘divergent economic interests, underlying cultural differences, a concern to preserve New Zealand’s financial and political autonomy, and the view that continuing free trade, cooperation and mutual military support would be possible without the need for full federation’.

Accordingly, at the suggestion of the New Zealand delegates, NSW Premier Henry Parkes’ proposed resolution calling for ‘an early union under the Crown of all the Australasian Colonies’ was changed to refer only to the Australian colonies, with a second added resolution that ‘the remoter Australasian Colonies shall be entitled to admission [to the union] at such times and on such conditions as may be hereafter agreed upon’.

New Zealand was again represented at the National Australasian Convention convened in Sydney the following year to draft a federal constitution. There, Captain William Russell, Colonial Secretary for New Zealand, argued the Conference should focus not on ‘the creation of one large colony on the continent of Australia’ but ‘to frame a constitution that all parts of Australasia shall be able to attach themselves to it should they now or hereafter think fit to do so’:

Although we do hesitate … in New Zealand, to submit ourselves to federation, I should not like the world to think that we are inimical to the idea at all. Though we may be unwilling to submit ourselves to any drastic laws, although we are unwilling to abrogate any of the powers of government necessary for our internal management, which we possess at the present time, there are all sorts of laws to which we shall be only too happy to submit ourselves if we are able to do so.

New Zealand did not participate in the Australasian Federal Convention which met in 1897 and 1898 and produced the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill, which was subsequently endorsed by referenda in each Australian colony in 1898, 1899 and 1900. However, the road to union remained open as the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (UK) provided ‘for admission into the Commonwealth of other Australasian Colonies and possessions of the Queen’ (preamble) including New Zealand specifically (covering clause 6).

On 26 December 1900, on the initiative of Prime Minister Richard Seddon, New Zealand Governor-General, Sir Uchter John Mark Knox Ranfurly, appointed a Royal Commission ‘for the purpose of inquiring as to the desirability or otherwise of our … colony federating with the Commonwealth of Australia’. The Commission was chaired by Colonel Albert Pitt, a Member of the New Zealand Legislative Council.

After taking evidence in New Zealand, the commissioners toured the newly federated Australia from 16 March to 24 April 1901, visiting every capital city apart from Perth, and the South Australian wineries. Of the 186 ‘New Zealand submissions, 114 were against, 49 were in favour, and 22 were non-committal’.[1] While noting that in Australia they found the most friendly feeling towards New Zealand, in the end the commissioners concluded it was not desirable that New Zealand should federate with and become a State of the Commonwealth of Australia:

Your Commissioners, ... with their knowledge of the … productiveness of New Zealand, of the adaptability of the lands … for close settlement, of her vast natural resources … the energy of her people, of the abundant rainfall and vast water power she possesses, of her insularity and geographical position; remembering, too, that New Zealand as a colony can herself supply all that can be required to support and maintain within her boundaries a population which might at no distant date be worthily styled a nation, have unanimously arrived at the conclusion that … New Zealand should not sacrifice her independence as a separate colony, but that she should maintain it under the political Constitution she at present enjoys.

The report was not debated in the New Zealand Parliament. Instead Prime Minister Seddon advocated a system of imperial federation and that New Zealand annex various islands of the South Pacific to establish a ‘Dominion of Oceania’.[2] Neither proposal came to fruition.[3]

In April 1901 in his anonymous column in the Morning Post, Alfred Deakin observed,

If the Commonwealth is to be perfected, it must include New Zealand. It must become Australasian instead of Australian. Of course, this ideal has long floated entrancingly before the eyes of our public men …The choice lies with her and not with us. As far as can be judged to-day, she is not desirous of being absorbed upon the state of the mainland. She is prosperous and self-sufficing. Her spirited people are proud of her distinctive characteristics and confident of her future …. Nothing offends them more than to confuse them with Australians or to regard their lovely and well-watered country as a mere Australian Island. Their pride is to regard themselves as belonging to another and separate sphere, and as being the ‘Great Britain of the South’.[4]

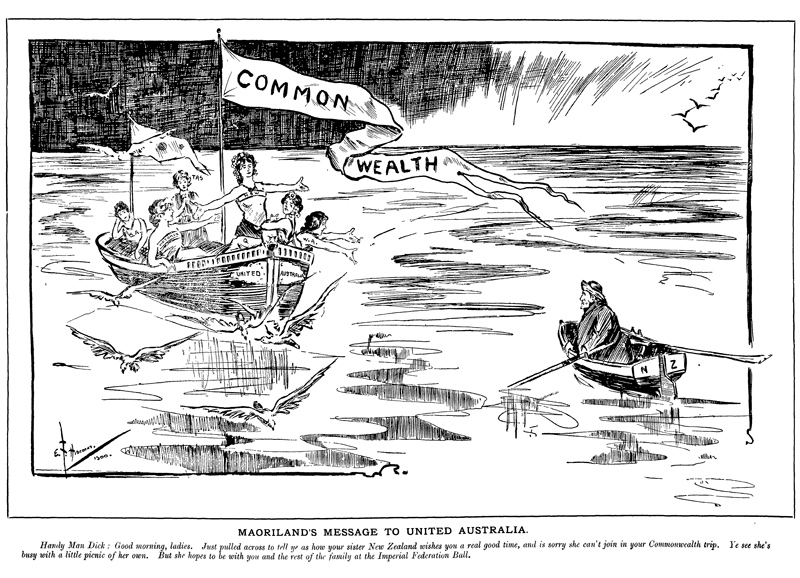

Image caption: "Handy Man Dick : Good morning, ladies. Just pulled across to tell ye as how your sister New Zealand wishes you a real good time, and is sorry she can't join in your Commonwealth trip. Ye see she's busy with a little picnic of her own. But she hopes to be with you and the rest of the family at the Imperial Federation BalL"

Source: New Zealand Free Lance, 5 January 1901, p. 7., National Library of New Zealand.

[1] R Palenski, The making of New Zealanders, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2012, p. 184.

[2] K Sinclair, A destiny apart: New Zealand’s search for national identity, Allen & Unwin/Port Nicholson Press, Wellington, 1986, p. 122.

[3] J Rolfe, ‘New Zealand and the South Pacific’, Revue Juridique Polynésienne, 1, 2001, pp. 161-162. See also: A Ross, New Zealand aspirations in the Pacific in the nineteenth century, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1964.

[4] A Deakin, Federated Australia: selections from letters to the Morning Post 1900-1910, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1968, pp. 6-7.