Key issue

COVID-19 has greatly disrupted school education, placing immense pressure on students, parents and carers, as well as highlighting disparities in education.

Reform initiatives and how to address the challenges of declining student performance in Australian schools will continue to be a source of debate in the coming years. Improving equity in schooling will be a critical area of focus.

Current issues facing schooling in Australia include recovery from COVID-19 and teacher workforce shortages.

Schooling in Australia

Although school education in Australia is primarily

the responsibility of the states and territories, the Australian

Government plays a role in funding schools and in national policy

initiatives and reforms. State and territory and Australian Government

education ministers make decisions and work collaboratively on education

matters through the Education

Ministers Meeting (previously the Education Council). In

December 2019, education ministers agreed to the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration

(Mparntwe Declaration), which sets out shared goals for education.

In 2021, there were more than 4

million students enrolled in Australia’s 9,581 schools. Of the total, 65.1%

were enrolled in government schools and 34.9% in non-government schools- comprising

19.5% in Catholic schools and 15.4% in independent schools. The proportion

of students enrolled in government schools in 2021 fell by 0.5 percentage

points from 2020, while the proportion of students in Catholic and independent

schools increased by 0.1 and 0.4 percentage points respectively.

Government funding for schools

The Australian Government provides the

majority of public funding for non-government schools and the minority of

public funding for government schools. These responsibilities are reversed

for state and territory governments.

In 2019–20, total government recurrent expenditure on schools

was $70.6 billion or $17,779 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student. Table

1 shows recurrent expenditure by state and territory and Australian governments

(totals and per FTE student) for government and non-government schools. Recurrent

expenditure refers to government funding granted to schools to meet their general recurrent costs of providing school education. It does not

include capital expenditure or special circumstances funding.

Table 1 Government recurrent

expenditure on school education, 2019–20

|

Government schools |

Non-government schools |

Total |

|

($b) |

($ per FTE) |

($b) |

($ per FTE) |

($b) |

($ per FTE) |

| State and territory governments |

44.2 |

16,936 |

4.1 |

2,978 |

48.2 |

12,139 |

| Australian Government |

8.5 |

3,246 |

13.9 |

10,211 |

22.4 |

5,640 |

| Total government |

52.6 |

20,182 |

18.0 |

13,189 |

70.6 |

17,779 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment

and Reporting Authority, ‘Government Recurrent Expenditure on Government and Non-Government

Schools,’ National Report on Schooling in Australia- Data Portal.

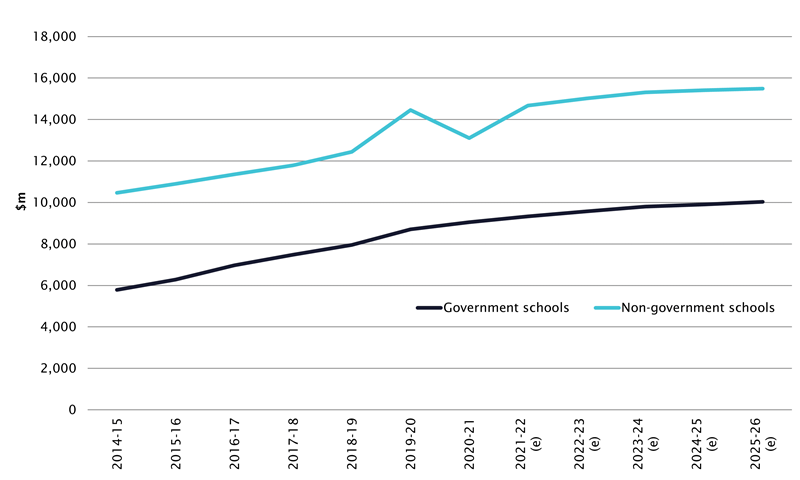

Over time, Australian Government expenditure on

schools has continued to increase (Figure 1). The rise then dip in expenditure between

2019–20 and 2020–21 for non-government schools was due to a COVID-19 response measure which brought forward

$1.0 billion of payments from July 2020 to May or June 2020 to encourage

non-government schools to return to classroom teaching (p. 118).

Figure 1 Australian Government

expenditure on schools sub-function- government and non-government schools ($m),

real 2021 dollars

Notes: Real funding has been calculated by

the Parliamentary Library by deflating the nominal expenditure figure by the June

quarter CPI. Figures are in 2020–21 dollars, the last available year of actual

figures.

Sources: Australian Government, Final

Budget Outcome, multiple years, Table A.1; Australian Government, Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, 150.

Educational goals and student performance in

Australia

Improving the quality of education and the

performance of students is a key driver of educational funding and reforms in

Australia. A chief concern for successive governments has been reversing

declines in student performance as measured by international assessments such as

the OECD’s (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Developent) Programme for International Student Assessment

(PISA).

Programme for International Student Assessment

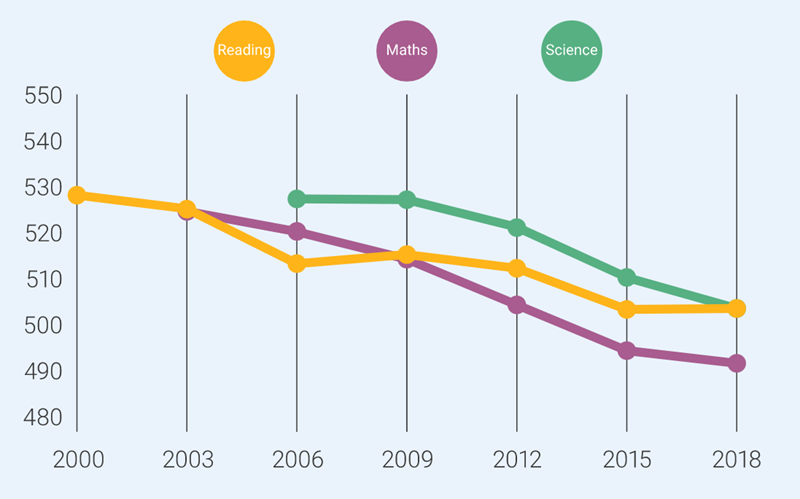

As shown in Figure 2, from PISA’s first cycle in 2000 to the most

recent in 2018, Australia’s mean scores (y-axis) have declined across all

domains. Each PISA cycle has a major domain, with reading first in 2000, maths

in 2003, and science in 2006.

Figure 2 Australian achievement

trends in PISA- mean scores in assessment domains

Source: Australian Council for Educational

Research (ACER), ‘Key Findings 2018’, ACER website.

In terms of years of schooling, Australia’s

performance in 2018 was the equivalent of about 1½ years lower than the

highest performers (the provinces of Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang,

China) in reading; 3½ years lower in mathematics; and more than 3 years lower

in science (pp. 3–5).

From when testing began to 2018, Australian students’

performance declined by the equivalent of more than a year in maths and

nearly a full school year in reading and science.

However, some experts have questioned using

a single standardised assessment as evidence of academic decline. Results for

Year 9 students from Australia’s National Assessment

Program- Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) show student achievement remaining

relatively steady since testing began in 2008. Another international test, Trends in International Mathematics and

Science Study, which tests students in Years 4 and 8 in maths and science,

shows that from 1995 to 2019 Australia’s mean student performance

improved in Year 4 maths and Years 4 and 8 science.

Recent reforms and developments

Reminiscent of Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s 2012 goal

to return

Australia to the top 5 countries in reading, mathematics and science by 2025,

Minister for Education and Youth Alan Tudge announced in March 2021 that

he would take to the next Education Ministers Meeting ‘a 2030 target to be

again amongst the top group of nations across the three major domains of

reading, maths and science’ (p. 5). Minister Tudge highlighted 3 areas of

focus: quality teaching, curriculum and assessment. Of these, he identified

quality teaching as the most important in-school factor determining student

performance and announced a review of initial teacher education (ITE).

Quality ITE Review

The Quality

ITE Review was undertaken by an expert

panel chaired by former Department of Education and Training Secretary,

Lisa Paul. The final report of the review, released in February

2022, made 17 recommendations across 3 key areas:

- attracting high-quality,

diverse candidates into initial teacher education

- ensuring their preparation is evidence-based and

practical

- supporting early years

teachers.

In response, the Government announced a new Initial Teacher

Education Quality Assessment Expert Panel which would develop new standards for

ITE courses and advise the Government on linking standards to ITE funding. The 2022–23 Budget also included funding for the

review response (pp. 77–8). The Coalition outlined further initiatives in its

election policy ‘Our plan for raising school standards’.

Review of the Australian Curriculum

The Australian

Curriculum sets out expectations for what Australian students should be

taught. State and territory and non-government school education authorities are

responsible for delivering the curriculum.

In 2015, education ministers agreed that the Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting

Authority (ACARA) should review the Australian Curriculum every 6 years, commencing

in 2020–21. In December

2019, the Education Council asked ACARA to develop terms of reference for

a review of the Foundation to Year 10 Australian Curriculum. The Education

Council endorsed the terms

of reference and review timelines in June

2020.

As with the previous

review of the Australian Curriculum in 2014, the 2020–21 review reignited

the ‘history wars’- debates about which aspects of Australian history should

be taught to Australian students. In August 2021 the Australian reported

on a letter sent by Minister Tudge to ACARA in which he criticised the draft

curriculum for ‘supporting “ideology over evidence” and presenting “an overly

negative view” of the nation in the study of history and civics’ and warned

that he would not endorse the proposed curriculum if ACARA did not

substantially rewrite the draft.

Education ministers

considered the final draft of the revised curriculum at their meeting in

February 2022. Afterwards, Acting Minister for Education and Youth Stuart Robert stated

that the Australian and Western Australian governments had concerns regarding

mathematics and humanities and social science, and had asked ACARA to revise

the curriculum and return to education ministers in April. Following ACARA’s revisions to the 2 learning areas, education ministers endorsed the updated curriculum

on 1 April 2022.

Whether there will be an abatement in the

‘curriculum wars’ is unclear. On

31 May 2022 Opposition Leader Peter Dutton stated that the national

curriculum and the values argument would be one of the big debates of the next Parliament.

However, in

response, Minister for Education Jason Clare said he was ‘not interested in

picking fights’ over the curriculum.

National School Reform Agreement

When announcing the Quality ITE Review in 2021,

Minister Tudge stated:

‘I have watched or been involved in the funding debate for many years and I am

pleased that the school funding wars are now over’.

However, debates over school funding are likely to

have renewed relevance during the 47th Parliament as the Australian Government

and state and territory governments negotiate the next national reform

agreement.

Under the Australian

Education Act 2013 (the Act), a condition of receiving Australian

Government funding for schools is that states and territories sign on to a

national agreement relating to school education reform and have an agreement

with the Australian Government relating to the implementation of reform.

The current agreement, the National

School Reform Agreement (NSRA), commenced on 1 January 2019 and

expires on 31 December 2023. It is supported by bilateral

agreements between the states and territories and the Australian

Government. As well as outlining state-specific actions to improve student

outcomes, bilateral agreements also set out minimum state and territory funding

contributions required to receive Australian Government school funding.

To inform the development of a new national reform

agreement, the NSRA requires an independent review to be completed by 31

December 2022 (section 29). In April 2022, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg requested

the Productivity Commission review the NSRA. The Productivity Commission

will assess the effectiveness and appropriateness of the national policy

initiatives set out in the NSRA, and the appropriateness of the Measurement

Framework for Schooling in Australia in measuring progress towards the NSRA’s

outcomes. The Productivity Commission will make recommendations to inform the

next school reform agreement and improve the Measurement Framework. In May

2022, the Productivity Commission released

a paper and called for submissions by 17 June 2022.

Equity in funding for government and non-government

schools will likely feature prominently in debates about a new school reform

agreement.

In 2017, the Turnbull Government announced reforms to the needs-based funding

arrangement. The Australian Education Act 2013 was

amended to stipulate that the Australian Government would move

towards consistent funding for schools of 20% of the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS) for government

schools, and 80% for non-government schools. Schools funded

below the consistent Australian Government share of their SRS will transition

up to the target share by 2023, while schools funded above will transition down

to the target share by 2029.

The Act requires state and territory governments to

make minimum funding contributions. The aim is for state and territory

governments to transition to consistent shares of at least 75% of SRS for

government schools and 15% for non-government schools. The target

is for all schools to be funded to at least 95% of their SRS by 2023 (Australian

and state and territory government shares combined).

However, the Act allows for the prescribed

percentages to be negotiated- bilateral agreements between the

Commonwealth and individual states and territories identify the agreed minimum

state contribution shares as a percentage of the SRS. Table

2 summarises these agreed minimum funding shares and shows that not all

jurisdictions will meet the target share rate of 75% for government schools and

15% for non-government schools by 2023.

Table 2 State and territory

government minimum contribution shares in bilateral agreements (%)

| State |

Sector |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

| ACT |

Gov |

80.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

| Non-gov |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

| NSW |

Gov |

70.73 |

70.84 |

71.05 |

71.37 |

71.80 |

72.22(a) |

| Non-gov |

25.29 |

24.70 |

24.23 |

23.76 |

23.29 |

22.82 |

| NT |

Gov |

55.20 |

56.00 |

57.00 |

58.00 |

58.50 |

59.00 |

| Non-gov |

15.09 |

15.09 |

15.09 |

15.09 |

15.09 |

15.09 |

| Qld |

Gov |

69.26 |

69.26 |

69.26 |

69.26 |

69.26 |

69.26(a) |

| Non-gov |

23.18 |

22.70 |

22.45 |

21.84 |

21.23 |

20.61 |

| SA |

Gov |

75.00 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

| Non-gov |

19.72 |

19.72 |

19.72 |

19.72 |

19.72 |

19.72 |

| Tas |

Gov |

72.93 |

73.16 |

73.39 |

73.62 |

73.85 |

74.08(a) |

| Non-gov |

21.50 |

21.20 |

20.90 |

20.60 |

20.30 |

20.00 |

| Vic |

Gov |

67.80 |

68.02 |

68.42 |

68.99 |

69.68 |

70.43 |

| Non-gov |

19.70 |

19.76 |

19.82 |

19.88 |

19.94 |

20.00 |

| WA |

Gov |

84.43 |

80.56 |

77.56 |

75.46 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

| Non-gov |

26.30 |

25.72 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

Note: (a) NSW, Queensland and Tasmanian state

governments have committed to reach 75% of the SRS for the government school sector

beyond 2023.

Sources: Compiled from bilateral

agreements under the National

School Reform Agreement, available from Department of Education, Skills and

Employment website.

The

Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian

Greens have been critical of these funding arrangements that will see non-government

schools funded at or above their SRS, while government schools will not get to

more than 95% of the SRS funding. During the election, the ALP committed

to, with the states and territories, getting all schools to 100% of the SRS.

The Greens’ election

platform included policies to increase funding for government

schools, promising to ‘fully fund’ government schools by increasing the

Australian Government’s share of the SRS from 20% to 25% to ensure government

schools would receive 100% of the SRS by 2023. The Greens also pledged to

‘remove the 4% capital depreciation tax in school funding bilateral agreements

and work with states and territories to ensure they maintain their commitment

to funding at least 75% of the Schooling Resource Standard’ (pp. 2–3).

Looking forward- challenges for Australian

schooling

COVID-19 recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused major

disruptions to school education in Australia. Across 2020 and 2021, several

jurisdictions instituted periods of remote learning to minimise COVID-19

transmission. In January 2022, National

Cabinet agreed to the National Framework for Managing COVID-19 in Schools

and Early Childhood Education and Care (pp. 4; 13–14) which aimed to ensure

schools and early childhood education and care services would remain open, with

face-to-face learning prioritised. While widespread school closures are not

currently in place, schooling continues to be affected by the pandemic. High

COVID-19 case numbers are placing pressure on staffing with teacher

absences leading to localised returns to remote learning.

A major area of concern at the start of the pandemic with schools

moving to remote learning was the potential impact on students’ learning,

particularly for vulnerable and disadvantaged children. However, results from NAPLAN in 2021 showed that, in

comparison to 2019, ‘achievement in numeracy, reading and

writing remained largely stable at a national level for all students’. ACARA noted

that there were indications of widening gaps between high and low

socio-educational groups between 2019 and 2021, and was undertaking further

analysis to understand whether this could be attributed to the impact of the

pandemic or was part of a longer-term national trend.

There are also concerns about the impacts of COVID-19 on student

wellbeing. A study from the Australian National University reported parents’ and carers’ perspectives on the mental health of children

and young people aged 18 years and under. Parents and carers believed

that COVID-19 had had a large impact on children and young people aged 5–18 years, with the mental health of those aged 15–18 of

particular concern. Comparing results with a 2020 survey, negative mental

health impacts appeared to have worsened, particularly for children in states with

long lockdowns.

States and territories have implemented various measures to support

students’ learning and wellbeing in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic,

including tutoring programs and funding for wellbeing and mental health services.

Ensuring schools and students are adequately supported in the

recovery from COVID-19 will be a priority for all governments in the coming

years. In particular, addressing disparities in education to ensure that disadvantaged students are supported will be

vital.

Election commitments from the Greens and the ALP included

measures to assist schools recover from the pandemic. The ALP promised

$440 million to improve air quality, upgrade buildings and support mental

health. As part of its capital funding commitment,

the Greens committed $224.1 million to install ventilation and air purifiers in

schools (p. 1).

Teacher shortages

Attracting and retaining teachers will be a central

challenge for schools. A recently

published study of 2,444 primary and secondary school teachers in Australia

found that only 41% of respondents intended to remain in the profession.

Reporting on data collected in 2019, the study indicated teachers’ reasons for

intending to leave the profession included heavy workloads, health and

wellbeing concerns, and the low status of the profession. The COVID-19 pandemic

has exacerbated

burdens on teachers and is likely to increase

teacher shortages.

There are additional challenges with attracting

teachers to rural and remote locations. In 2019, the Australian Government introduced

incentives for teachers to teach in very remote locations through reduced

Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) debts.

The significant challenges of attracting people to teaching were

noted in the Quality ITE Review’s final report. The expert

panel considered that its recommendations would significantly alleviate

teacher workforce challenges if implemented (p. iii).

The ALP’s election commitments included plans

for addressing teacher shortages and improving teaching quality through

initiatives to attract high-achieving students to teaching and to attract talented

teachers to rural, regional and remote areas. It also promised funding to

retain teachers through better career paths, and to respond to the Quality ITE

Review.

The Coalition

criticised Labor’s education platform for being silent on school standards.

It committed to strengthening teacher training and lifting student performance

through ITE initiatives, facilitating mid-career professionals to become

teachers, and supporting ‘positive learning environments’ in classrooms.

Considerations for the incoming Parliament

The Mpartnwe Agreement includes

the twin goals for the Australian education system to promote excellence and

equity. As discussed above, a major policy focus has been on excellence in

terms of returning Australia to the top of world-rankings. However, the OECD

states ‘the highest performing education systems are those that combine

equity with quality’ (p. 3). In terms of

inequality, Australia’s education system is in the bottom third of OECD

countries (pp. 8; 10). Making progress towards

improving equity and reducing inequality in Australian schooling will be an important

and complex issue for the incoming Parliament to consider.

Further reading

Shannon Clark, COVID-19: Chronology of State and Territory Announcements on Schools and Early Childhood Education in 2020, Research paper series, 2021–22 (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2022).

Shannon Clark and Hazel Ferguson, ‘Report of the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review- Implications for Higher Education’, FlagPost (blog), Parliamentary Library, 23 March 2022.