Australia’s current account balance is forecast by the Treasury to go into deficit in the 2022–23 financial year. The current account records the value of the flow of goods, services and income between Australian residents and the rest of the world. The Treasury’s budget modelling indicates that the projected current account deficit will be driven by weaker global demand for Australian exports and a fall in commodity prices.

History of Australia’s current account balance

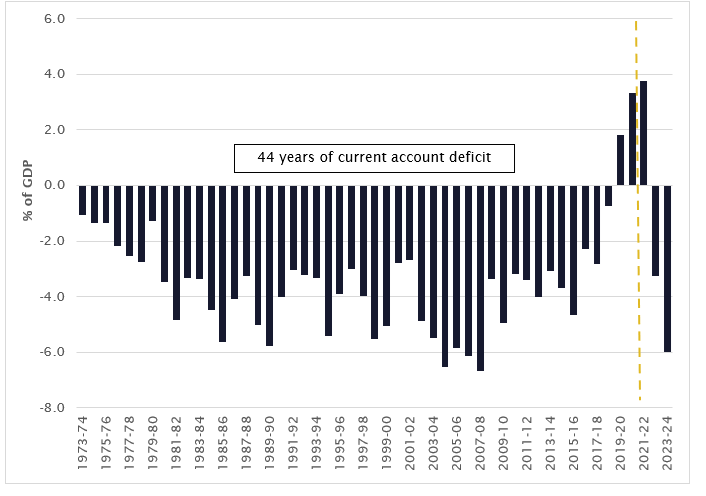

Australia had a current account deficit for 44 years from September 1975 to September 2019 (see Figure 1). A current account deficit indicates a country imports more goods and services and income from abroad than it exports overseas. A trade deficit – when a country spends more money on imports than it makes on exports – is normally the largest component of a current account deficit.

Figure 1 Australia’s current account balance as a percentage of GDP

Source: Current account data from 1973–74 to 2020–21 is sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (previously Cat. No. 5302.0). Forecast data from 2021–22 to 2023–24 is taken from Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, p. 37.

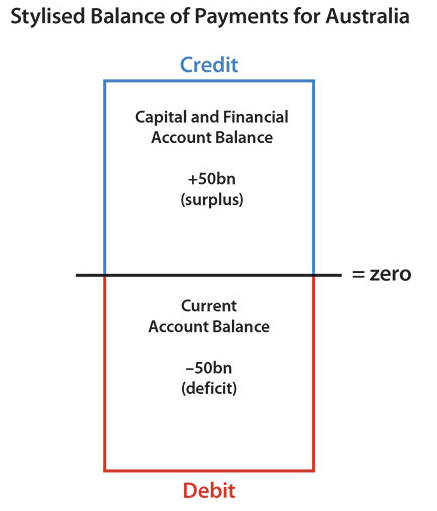

A country’s balance of payments must sum to zero because in theory the current account is always offset by the capital and financial account (see Figure 2). To give an oversimplified example, if a country imports $50 billion worth of goods from overseas but exports nothing in return, then it could sell $50 billion worth of assets to foreigners and use the income to pay for the imports. This means the country’s $50 billion current account deficit (driven by its trade deficit) is offset by an equivalent surplus in its capital and financial account (i.e. income received from selling assets to foreigners), therefore the sum of the balance of payments is zero.

Given Australia’s history of current account deficit, by definition Australia was also running a capital and financial account surplus for 44 years. In other words, for a long time Australia was a net capital-importing country to finance its consumption of imports.

Furthermore, Australians did not have enough domestic savings to finance the abundant investment opportunities available here, therefore foreign capital was flowing into Australia to invest in and purchase Australian assets.

Figure 2 The current account is always offset by the capital and financial account

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia, ‘The Balance of Payments’ Explainer.

Recent trends in Australia’s current account balance

Australia’s net capital-importing status was reversed in September 2019 when the country recorded its first quarter of current account surplus in 44 years – a trend that has continued to the present. The surplus has been predominantly driven by Australia’s strong exports, fuelled by record-high prices for iron ore.

While Australia has been exporting more goods and services than it imports since September 2019, money has flowed out of Australia in exchange for increased ownership of foreign assets, including Australian superannuation funds’ purchasing of overseas equities.

The latest ABS data shows Australian investment abroad increased by $275.3 billion from 2020 to 2021. Foreign investment into Australia increased by only $92.3 billion over the same period. The larger increase in Australian investment abroad affirms that Australia is now a net capital-exporting country.

In concurrence with Australia’s current account surplus trend, concerns over national security and potential panic sales of Australian assets at the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic have led to a tightening of Australia’s foreign investment policy since 2020. In other words, it has been more difficult for some foreign investors to purchase Australian assets, and this has contributed to Australia’s net capital-exporting status.

Looking ahead

Australia’s current account surplus is not projected to continue. The 2022–23 federal Budget forecasts that Australia’s current account balance will go into deficit in 2022–23 (see Table 1 below). The deficit is expected to widen from 3.25% of GDP in 2022-23 to 6% in 2023–24.

Table 1 Projected current account balance

|

|

Outcomes

|

Forecasts

|

|

2020–21

|

2021–22

|

2022–23

|

2023–24

|

|

Terms of trade

(percentage change on preceding year)

|

10.4

|

11

|

-21.25

|

-8.75

|

|

Current account balance

(% of GDP, a positive number indicates surplus and a negative number indicates deficit)

|

3.3

|

3.75

|

-3.25

|

-6

|

Source: Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, p. 37.

The projected current account deficit and decline in Australia’s terms of trade reflect the Treasury’s forecast that:

- strict COVID lockdown and economic growth slowdown in China will undermine Australian commodity exports to China (Budget Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, p. 40)

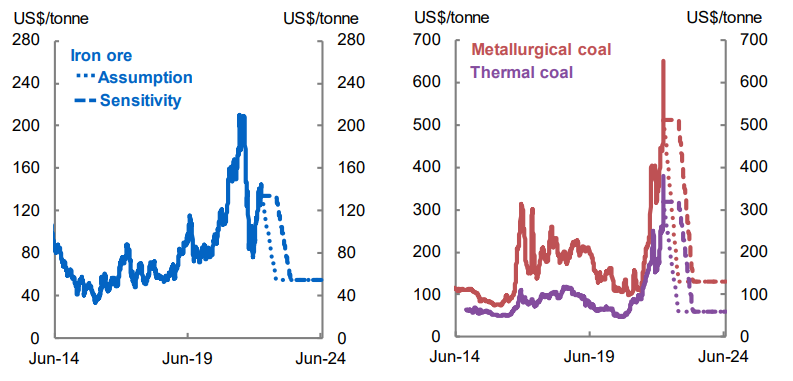

- commodity (particularly iron ore and coal) prices will decline from current elevated levels to levels consistent with long-term economic fundamentals (pp. 63–64) (see Figure 3).

Put simply, the Treasury thinks Australian commodity exporters could have some difficult years ahead due to weaker demand and falling prices.

Figure 3 Iron ore and coal spot price assumptions shown in the 2022-23 federal Budget

The Treasury acknowledges that iron ore prices are volatile and uncertain (p. 214), and it uses conservative assumptions regarding the price movement of key commodities (p. 63). This means the budget forecasts do not necessarily reflect the Government’s future expectations. Conservative assumptions are useful to prepare for ‘worst case’ scenarios.

Not everyone agrees with the Treasury’s conservative forecast. For example, Stephen Bartholomeusz of the Sydney Morning Herald says a collapse of commodity prices is possible, but unlikely. This is because key commodity prices are influenced by demand in China, whose economic outlook is uncertain.

Chris Murphy, a research fellow from the Australian National University, says the Budget’s forecast for a large current account deficit is unrealistic because the Treasury incorrectly assumes the Australian dollar’s exchange rate will remain around its recent average level (a trade‑weighted index of around 60 and a US exchange rate of around 72 US cents).

The Australia dollar is known as a ‘commodity currency’, meaning there is a close relationship between global commodity prices and the value of the Australian dollar due to Australia’s dependency on export of raw materials for income. Put simply, a fall in commodity prices is expected to come with a corresponding depreciation of the Australian dollar. A weakened Australian dollar could then provide a boost for Australian exporters, thereby undercutting the Treasury’s forecast for weaker exports and a large current account deficit.

On the other hand, the recent decision by the Reserve Bank of Australia to raise interest rates coincides with the Treasury’s projected current account deficit. In the unlikely scenario that Australia’s interest rates rise above US and European interest rates, then more foreign capital will flow into the country and contribute to the projected deficit.

Economists disagree on whether a persistently large current account deficit signals deeper economic problems. As with most things in life, the answer is ‘it depends’. The Albanese Government will need to decide whether it should manage the deficit if the Treasury’s forecast is borne out.

Further reading:

- Atish Ghosh and Uma Ramakrishnan, ‘Current Account Deficits: Is There a Problem?’, International Monetary Fund, 24 February 2020.

- John Kehoe, ‘The surplus that is bad news for the economy’, Australian Financial Review, 10 September 2021.

- Ross Gittins, ‘Our dealings with the world have reversed, but don’t get the wrong idea’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 August 2021.