In the wake of World War II Australia pressed the US for a treaty to protect the Pacific from Japanese expansionism and communist ideology emanating from China and Russia. The outcome was the ANZUS treaty, concluded in San Francisco on 1 September 1951. The aims were peace and protection; the means were military. The treaty has been central to the Australia-US alliance ever since, and its configuration and implementation have evolved over time—as have the security challenges.

In a recent speech to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore, US Secretary of Defence, Lloyd Austin, acknowledged traditional security challenges, such as nuclear proliferation and dictatorial regimes, but also noted transnational threats ‘like the pandemic and the existential threat of climate change’.

Alongside the geopolitical shifts since 1951, climate change is now identified as a significant threat multiplier globally, particularly in the Pacific. Pacific nations face diverse climate change related problems that have been shown to precipitate some security threats and exacerbate pre-existing ones. These include, but are not limited to:

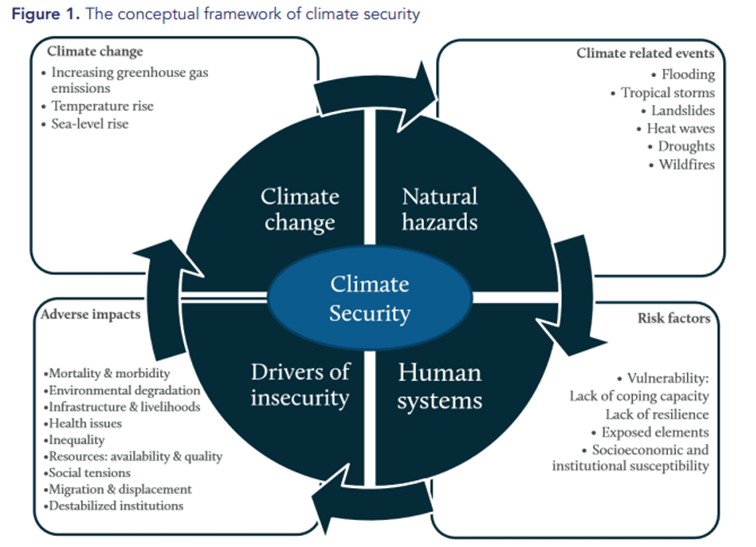

The World Climate and Security Report 2021 by the International Military Council on Climate and Security conceptualises climate security as follows (p. 20):

Addressing climate-related threats to the Pacific will be fundamental to regional stability, as Pacific nations attempt to diversify their economies beyond tourism and primary production. To reduce immediate threats in the Pacific and work cohesively to ‘share the burden’ (along with New Zealand), the US and Australia may need to find common ground (pp. 52–55) in their relevant policies. US Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken, linked domestic climate policy with foreign policy when he indicated an intention to ‘leverage our foreign policy to deliver for the American people on climate’. He laid out a six-point plan that involves:

- putting ‘the climate crisis at the centre of our foreign policy and national security’

- sharing private and government resources, knowledge and expertise with countries which ‘step up’ on climate action

- deploying experts and technology to ‘vulnerable islands in the Pacific and Caribbean’

- assisting other governments to ‘design and implement climate-smart policies’ and projects

- improving the competitiveness of US clean energy innovation and

- diplomacy that will ‘challenge the practices of countries whose action – or inaction – is setting the world back’, meaning that ‘when countries continue to rely on coal ... or allow for massive deforestation’, for example, ‘they will hear from the United States…’.

The US has signalled that the ANZUS alliance forms part of this approach. In a statement, ‘Celebrating 70 Years of the ANZUS treaty’, Blinken declared it was ‘more than a military pact’, noting that it also functioned to ‘assist our Pacific neighbors, and cooperate on issues of global concern, such as public health and climate change’. ANZUS, like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), may need to develop a climate change action plan.

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) made similar observations in its submission to the 2017 Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade Committee inquiry into the Implications of climate change for Australia’s national security. It posited that both national and human security are ‘inherently linked to the security of health, water, energy, food and economic systems at the local, national, regional and global level’, and that climate change represented a ‘threat multiplier’. The ADF said it was ‘progressively embedding climate change into its core business functions’ (p. 3), noting that the expected increased need for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) may ‘create concurrency pressures for Defence’ from the mid-2020s, or ‘earlier if climate related impacts on security threats accelerate’ (p. 6).

Australia has also reckoned with its own ‘era of disasters’ domestically and in the Pacific region. The ADF was integral to combating and recovering from the bushfires that gripped Australia in 2019–20 and has regularly provided HADR to help rebuild Pacific communities. A recent academic assessment found that HADR also assists in building and strengthening informal security networks that may ‘soft balance’ Chinese influence in the region. However, it concluded that ‘despite a shared language, broadly similar regional goals, and a shared need for interoperability; strategic coordination on HADR is absent’ (p. 73). The research credits HADR operations with returning New Zealand to the ‘ANZUS fold’ (p. 80), but warns alliance partners need to consolidate and coordinate future HADR efforts.

A climate security action plan formed part of the September 2021 report, Missing in Action: Responding to Australia’s Climate and Security Failure, published by advocacy group Australian Security Leaders Climate Group. It recommends Australia ‘cooperate with big and small Asia-Pacific governments to build alliances for climate action, understanding that cooperation rather than conflict is key to responding to the climate crisis’ (p. 40). ANZUS partners’ involvement in other multilateral treaties may also oblige them to respond to climate change related security threats. For instance, Australia and New Zealand are signatories to the Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Ocean Statement of 2020–21, which calls for:

… urgent action to reduce and prevent the irreversible impacts of climate change on our Ocean, reiterating that climate change is the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Blue Pacific.

These regional expectations are also being expressed internationally. The World Climate and Security Report 2021 believes the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) will provide momentum to ‘lead strong climate security action’. The report pointed to ‘the unprecedented wildfires in the United States and Australia’ as examples of ‘new disasters hitting before societies can recover or adapt to the impact of previous ones’. The Biden administration’s whole-of-government approach to climate change and the recent Australia-US Ministerial Consultation (AUSMIN 2021) dialogue may represent a turning point in climate security in the Indo-Pacific. Reflecting on ANZUS in the wake of the AUKUS announcement, the AUSMIN Joint Statement ‘reaffirmed’ the Indo-Pacific as the ‘focus of the Alliance’, declaring that ‘in the face of challenges spawned by the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and growing threats to security and stability, our friendship stands steadfast and resolute’.