Processes for determining skills shortages, occupation lists and

skills assessments

3.1

This chapter discusses issues relating to how the occupation eligibility

settings for the temporary skilled visa system are determined, focusing

primarily on the Temporary Skills Shortage (TSS) visa subclass. These issues include:

- how occupations are placed on the three Skilled Migration

Occupation Lists (and how these lists are reviewed);

- the research and analysis undertaken by the Department of Jobs

and Small Business (DJSB) on which occupations are experiencing skills

shortages; and

- the role and functionality of the Australian and New Zealand

Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO), which underpins the skilled

migration lists.

3.2

This chapter also examines the skills assessment procedures that form

part of the TSS visa application process for certain occupations. This involves

Australian skills assessing authorities carrying out skills assessments of

overseas workers in order to determine their suitability to work in Australia

in their nominated occupation.

Placement of occupations on the skilled migration occupation lists

3.3

As noted in Chapter 2, employers can only nominate workers for a TSS

visa for occupations that are listed in an eligible Skilled Migration

Occupation List. The three relevant occupation lists were described in the

joint submission from the Department of Home Affairs, DJSB, and Department of

Education and Training (Joint Departmental Submission) as follows:

- Short-term Skilled Occupation List (STSOL): occupations required

to fill critical, short-term skills gaps (linked to the short term stream of

the TSS visa subclass).

- Medium and Long-term Strategic Skills List (MLTSSL): occupations

of high value to the Australian economy and aligned to the Government's longer

term training and workforce strategies (linked to the medium term stream of the

TSS visa subclass).

- Regional Occupation List (ROL): occupations to support regional

skills needs (also linked to the medium term stream of the TSS visa subclass).[1]

3.4

As of March 2019, there are:

- 215 occupations listed on the STSOL for the TSS visa;

- 216 occupations listed on the MLTSSL for the TSS visa; and

- 77 occupations listed on the ROL for the TSS visa.[2]

3.5

Examples of occupations on the short term list and medium to long-term

list (as of March 2019) are included in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Examples of occupations included in the skilled

occupation lists[3]

Short Term Skilled Occupation List |

Medium and Long Term Strategic Skills List |

Mechanical engineering and metallurgical

technicians |

Chemical, materials, civil,

geotechnical, electrical, industrial, mechanical, mining and petroleum

engineers |

Production managers (forestry,

manufacturing and mining) |

Architects, surveyors and

cartographers |

Sales, marketing, advertising,

corporate services, finance and human resources managers |

Accountants (general) and

taxation accountants |

Manufacturers |

Boat builders and repairers

and shipwrights |

Primary, middle school, art,

dance and music teachers |

Early childhood, secondary and

special needs teachers |

School principals |

Faculty heads and university

lecturers |

Café, restaurant, hotel,

accommodation and hospitality managers |

General practitioners,

cardiologists, neurologists, paediatricians and surgeons |

Enrolled nurses and nurse educators,

researchers and managers |

Midwives and registered nurses |

Finance, insurance and

stockbroking dealers |

Barristers and solicitors |

Advertising and market

specialists |

Motor, diesel motor,

motorcycle and small engine mechanics |

Newspaper editors and print

and television journalists |

Bricklayers, carpenters,

plumbers and electricians |

Bakers, pastrycooks, butchers

and cooks |

Chefs |

3.6

The Regional Occupation List includes, for example, aeroplane and helicopter

pilots, ship's masters, agricultural technicians, cattle and livestock farmers,

and financial institution branch managers.[4]

Recent updates to the skilled

migration occupation lists

3.7

DJSB is responsible for advising the Australian Government on which

occupations should be included in the skilled migration occupation lists.

However, the final decision on the composition of the occupation lists rests

with the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs.[5]

3.8

DJSB submitted that it 'regularly reviews the occupation lists to ensure

they reflect and address Australia's labour market needs'.[6] Updates to the skilled occupation lists based on DJSB advice occurred in July

2017, January 2018, March 2018 and March 2019.[7]

3.9

The most recent revision to the lists, announced on 11 March 2019, involved

the addition of eighteen occupations to the Regional Occupation List, including

livestock, beef, dairy, sheep, aquaculture and crop farmers, among other

agricultural roles, in order 'to further support regional and rural businesses,

particularly farms'.[8] Sixteen of these occupations were moved onto the ROL from the STSOL, meaning

that new TSS visa applicants in these occupations will be able to live and work

in Australia for up to four years (rather than two years under the short term stream).[9]

3.10

Other changes contained in the March 2019 revisions included the

addition of eight new occupations on the MLTSSL (six of which were previously

included in the STSOL for the TSS visa).[10]

Process for updating the skilled

migration occupation lists

3.11

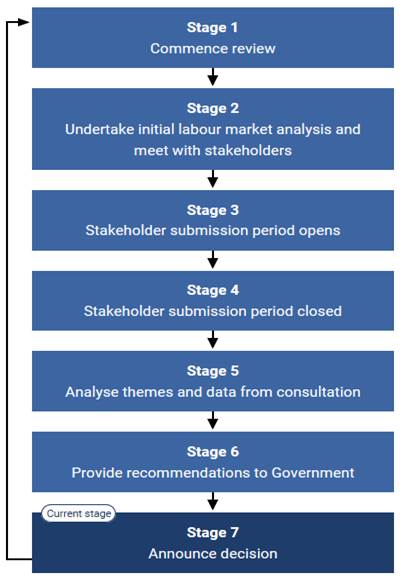

The DJSB website provides an overview of the process undertaken with

each review of the occupation lists, shown at Figure 3.1. DJSB advises that

stakeholders can contact the Department at any time, and formal consultation

occurs 'in the months leading up to when each review is scheduled to conclude'.

For example, for the January 2018 update the DJSB opened consultation in

November 2017.[11]

Figure 3.1: Overview

of the process for reviewing the Skilled Migration Occupation Lists[12]

3.12

In September 2017, DJSB released a consultation paper on the methodology

it uses to review the occupation lists. This consultation paper indicated that

DJSB would undertake labour market analysis for all Australian and New Zealand

Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) Skill Level 1 to 3 occupations,

comprising around 650 skilled occupations, every six months (see below for

a discussion of the ANZSCO framework).[13] Datasets DJSB uses to conduct this analysis include, for example, data taken

from across various government departments and agencies on:

- skilled migrant employment outcomes,

- graduate and apprentice outcomes,

- employment growth predictions,

- Australian skill shortages; and

- base salaries data.[14]

3.13

DJSB acknowledged some limitations in its methodology, arising partly

because of 'the need to use data at the national level, as data at the state,

territory or regional level is either not available or not as statistically

robust'.[15] DJSB noted that future versions of the paper will outline a new methodology for

the Regional Occupation List 'that uses data relevant to analysis on regional

labour market needs'.[16]

3.14

Mr Peter Cully, Group Manager, Small Business and Economic Strategy

Group at DJSB, commented further on the methodology and consultation process

followed by the department:

[The process is] as comprehensive as it can be with the data

that we have available. We're always looking at new sources of data emerging. A

lot of the time we will have submissions and other views put forward by

stakeholders, but there's not necessarily evidence or a dataset behind those.

So it's as comprehensive as it can be. We're certainly very committed to

consultation as a way to talk to stakeholders, to get their views and to

explain the process through them. So we've used a range of different stakeholder

engagement methods through the process: submissions to our website but also a

range of face-to-face meetings at industry level or with individual

stakeholders, depending on the circumstances.[17]

Skills shortages research by the

Department of Jobs and Small Business

3.15

DJSB is responsible for carrying out ongoing research on which skilled

occupations have shortages.[18] Its skill shortage research program covers more than 80 skilled

occupations on an annual basis, and focuses on occupations with long lead times

for training (generally requiring at least three years of post-school education

and training).[19]

3.16

The Joint Departmental Submission stated that this research 'provides

objective assessments of a subset of skilled occupations to meet various needs,

and identifies those in shortage at a particular point in time'.[20] DJSB draws on multiple datasets when determining skills shortages, including

quantitative and qualitative data taken from the Survey of Employers Who

have Recently Advertised.[21]

3.17

The skills shortages findings made by DJSB feed into its process for

determining which occupations are recommended to be placed on the Skilled

Migration Occupation Lists. The Joint Departmental Submission explained further

how these two processes interact:

While the skill shortage research is one factor in the

skilled migration occupation lists methodology, it is not determinative. Any

differences between these occupation lists reflects their different

methodologies; different purpose and different time-frames (that is, the DJSB

skill shortage lists reflect the current labour market, while the skilled

migration occupation lists consider future labour market needs).[22]

Submitter and witness views on the occupation lists and associated issues

3.18

Submitters and witnesses to the inquiry raised a series of issues

relating to the processes associated with the skilled occupation lists. These

included:

- concerns that the occupation lists do not reflect genuine skills

shortages;

- uncertainty for industry because of occupations being regularly

added, removed or transferred between the skilled occupation lists;

- complexity of the occupation lists;

- lack of transparency around how final decisions on changes to the

occupations lists are made; and

- potential shortcomings in consultation processes and the skills

shortages research methodology.

Concerns that the occupation lists

do not reflect genuine skills shortages

3.19

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) argued that the occupations

on the MLTSSL 'do not accurately reflect the genuine labour shortages in

Australia'. The ACTU suggested that according to DJSB's historical list of

skills shortages, of the top five occupations granted visas in the MLTSSL

stream—accountants, software engineers, registered nurses, developer

programmers and cooks— 'not one... was in shortage over the four years to 2017'.

It further contended that software engineer had 'never been in shortage in the

31 year history of the series'.[23]

3.20

Mr Damian Kyloh, Associate Director of Economic and Social Policy at

the ACTU, told the committee:

The occupations on the TSS visa list include roof tilers,

carpenters, joiners, chefs, cooks, midwives, nurses and real estate agents. The

empirical evidence, and the evidence from our side and our affiliates, is that

there aren't genuine skills shortages in all those professions.[24]

3.21

The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) noted that a

significant number of Australian nursing and midwifery graduates currently have

difficulty securing a job after completing their studies, and argued that the 'employment

of large numbers of offshore nurses' is a contributing factor in the

unemployment and underemployment of these graduates:

Many graduates and early career nurses and midwives struggle

to find employment in their chosen professions, and are often rejected by

employers who utilise temporary migrant labour. This is inconsistent with the

key temporary skilled migration policy objective that offshore workers should

not be engaged if there is a domestic worker willing and able to take up the

role.

The ANMF considers the failure of our system to provide work

for new graduates at a time when employers continue to access large numbers of

nurses and midwives on temporary work visa arrangements demonstrates a

disconnect between the current temporary visa system and the available supply

of new graduates. The ANMF accordingly queries the extent to which the

temporary visa system takes into account nursing graduate data.[25]

Uncertainty resulting from changes

to the occupation lists

3.22

Various organisations complained that the current system of skilled

migration lists is unnecessarily complex, and that the number of changes to the

lists in recent years has resulted in significant uncertainty for employers and

visa holders.

3.23

The Committee for Melbourne commented that the potential for changes

every six months to the occupation lists is 'creating greater uncertainty for

business, as well as for skilled foreign individuals who have expressed a

desire to live and work in Australia'.[26] This sentiment was echoed by the Minerals Council of Australia and several

other submitters.[27]

3.24

Uncertainty around the timing of revisions to the lists was also of

concern. A number of submitters expressed frustration that the most recent

revision to the skilled occupation lists had been delayed, with no revision

between March 2018 and March 2019, despite the government's commitment to

review the lists bi-annually.[28]

Arguments for a more gradual

approach to changing the skills lists

3.25

Noting that a large number of occupations had been removed from the

lists in recent years, the Law Council of Australia recommended that

consideration of whether to restrict access to occupations on the migration

lists should include assessing whether this is better managed through the

imposition of a caveat rather than placement on the STSOL or removal from the

occupation lists altogether.[29]

3.26

The Law Council recommended further that 12 months' notice should be

given prior to an occupation being removed. This would allow a six month period

for submissions and consideration, and a further six months for visa holders

and employers to plan and make alternative arrangements.[30]

Complexity of the occupation lists

3.27

Dr Carina Ford of the Law Council of Australia observed that the sheer

size of the occupations list, coupled with the various caveats that apply to

certain occupations, make it difficult to navigate.[31]

3.28

Ms Adrienne O'Rourke, General Manager of the Resources Industry Network,

explained at the committee's public hearing in Mackay how difficult it is to find

and interpret information on the skills lists:

I have gone round in circles on the Home Affairs website

trying to find information about the identified list of skills that you can

apply under. If you're a small business, it just must be such a struggle.

You're having to now pay consultants to do this. There's probably no chance of

you being able to do this yourself.[32]

3.29

Some stakeholders argued that the lists should be consolidated into a

single skilled migration occupation list. For example, Restaurant &

Catering Australia submitted:

[T]he dissection of the skilled occupation lists into the

STSOL and MLTSSL is an overly convoluted, confusing and complex system for

employers to navigate which may also have the effect of worsening already‑crippling

skills shortages. R&CA argues that this dichotomy has been flawed from the

outset and the two lists should be consolidated. The separation between each of

these lists adds an unnecessary layer of complication to the current skilled

visa framework, creating further difficulty for employers in terms of their

ability to navigate the current system.[33]

3.30

Mr John Hourigan, National President of the Migration Institute of

Australia, gave evidence that 'the number of occupation lists is confusing' and

advocated that 'the occupation list be reduced to a single list which clearly

identifies the visa subclasses which apply to each occupation'.[34]

Comments on specific changes to the

occupation lists in recent years

3.31

Some submitters argued that recent movements of occupations on the lists

have had a negative impact on some industries. For example:

- representatives from the independent schools sector stated that

the recent movement of the 'School Principal' and other school-related occupations

from the MLTSSL to the STSOL had an immediate and adverse impact on independent

schools;[35]

- Ports Australia argued that the removal of specialist maritime

roles from the occupation lists in 2017 is likely to lead to a void of

specialist mariners with the necessary skills and experience to fill key roles

in Australian Ports and other maritime sectors;[36] and

- Restaurant & Catering Australia submitted that pre-existing

skills shortages in the occupations of cook and café or restaurant manager have

been exacerbated following those occupations' removal from the MLTSSL in 2018.[37]

3.32

The committee also received various recommendations from submitters and

witnesses in relation to specific occupations and their placement (or

non-placement) on the occupation lists.[38]

Views on the adequacy of the skills

shortages research methodology

3.33

The committee heard some concerns about the methodology underpinning

DJSB's skills shortages research, which feeds into decision making processes

around the occupation lists.

3.34

Dr Gavin Lind, General Manager, Workforce and innovation at the Minerals

Council of Australia (MCA) commented that consultation around DJSB's skills

shortages methodology was lacking:

MCA is concerned that the data being used to determine

skills shortages is incomplete and out of date. It is also disappointing to

note that MCA...was not consulted or briefed for the skills shortage research

methodology. Any methodology that is applied needs to ensure that all the

relevant industry voices are captured and considered to secure and promote

accurate findings and ensure that the system is targeting genuine skill

shortages. For example, had MCA been consulted for the 2018 skills shortage

report, up-to-date figures and projections would have been provided, ensuring

that the current labour market rating for mining engineers was determined

through the application of relevant and accurate data.[39]

3.35

Science & Technology Australia commented that the methodology used

to establish a skills shortage has been effective when examining professions in

which a clear and uniform skills set is required, but does not accurately

account for the precision skills required by the research sector—a sector where

niche, and often scare, skills are the norm.[40] It also argued that measuring skills shortages on an annual basis 'provides a

limited and one-dimensional view of the workforce and cannot accurately capture

the number of skilled researchers that may be required for specialised work at

different times of the year, at different stages of the research cycle'.[41]

3.36

Housing Industry Association (HIA) argued that DJSB's requirement that

industry representatives provide robust modelling to underpin claims of skills

shortages is unreasonable:

Government liaison and consultation with industry is vital to

successful outcomes, especially in relation to the divergences in skilled

labour requirements across industries and also geographical regions and

localities. Detailed anecdotal evidence from industry is very powerful because

it stems from the people on the ground so the information is timely and

accurate. Providing robust modelling as well, which industry has been asked to

do for many years now, is difficult and costly to achieve and should be the

purview of the department, in consultation with industry.

Putting the onus on industry to provide robust modelling of

their skilled labour requirements, as has occurred to varying degrees over many

years, is not a viable or sensible approach.[42]

3.37

HIA recommended that DJSB be appropriately resourced to undertake

quantitative modelling of skilled labour demand, and provide a more

disaggregated analysis and assessment of skilled labour requirements for

temporary skilled migrants.[43]

Processes for making decisions

about composition of the occupation lists

3.38

The committee heard significant concerns about the lack of transparency

surrounding the final ministerial decision making process for adding and

removing occupations on the lists. For example, Australian Pork Ltd argued:

The Department of Jobs and Small Business (DJSB) methodology

underpinning the system of determining skills shortages appears robust at first

glance. It provides lists of relevant datasets and a description of the general

principles by which a skills shortage will be determined. It gives the pretence

of transparency but conceals the application of the methodology and its

detailed results. For example, there is reference to a point system, but no

specifics on how many points are awarded for each dataset, or details of points

thresholds for entry onto one or other of the TSS lists.

Changes in skills shortage categorisation for occupations,

including for horse-racing and for CEOs, have been made suddenly and in

apparent response to lobbying efforts or through special deals, rather than by

adherence to the DJSB methodology and points system[44]

3.39

The Migration Institute of Australia submitted similarly:

The process for determining what occupations are in shortage

and should be included in migration skilled occupation lists, is...not well

understood or transparent. Various industry and profession consultations are

known to occur, but anomalies exist in the outcomes of such consultations. For

example, certain professional and industry associations and trade unions appear

to have been able to protect those professionals or workers they represent, by

preventing these occupations being added to the skilled occupation lists, by

limiting the numbers permitted to apply or by having more rigorous labour

market testing requirements imposed.[45]

3.40

Restaurant & Catering Australia (R&CA) argued that the

government should be required to publicly release detailed reasoning for final

decisions made to change occupations included on the lists:

Frustratingly, there has been little justification...provided

as to [the] composition of the STSOL and MLTSSL and the inclusion of each

listed occupation, other than that these occupations are critical to the future

skills needs of the Australian economy and workforce. R&CA implores the

Commonwealth Government to provide proper reasoning and accompanying data

explaining the decisions for why certain occupations are either included or

excluded from the two lists for purposes of transparency.[46]

3.41

RDA Far South Coast expressed concern at the lack of regional input during

reviews of the skilled occupation lists:

Further compounding the inadequacies of the current lists, is

the manner in which they are determined. No direct regional consultation

currently occurs with city-based consultants studying on-line job ads to gauge

regional needs. As many regional employers use recruitment methods other than

these, the skills lists are intrinsically flawed. There is an obvious, yet

unrealised, need for direct regional input into the skills requirements.

Regions vary greatly and unfortunately, consultation is not occurring at the

grassroots level. [Regional Certifying Bodies] are ideally placed to provide

this input as most conduct regional skills audits through direct engagement

with both regional employers and training bodies.[47]

3.42

The Electrical Trades Union of Australia (ETU) argued that previously,

the STSOL, MLTSSL and regional skills lists were 'established and reviewed

following extensive consultation with representatives of Government, business,

workers and education providers which ensured that only genuine shortages made

it onto the register of eligible occupations'. The ETU suggested that the

dismantling of tripartite consultative bodies which previously provided advice

on skills shortages had led to significant issues with the skills lists, to the

point that the eligible occupations lists 'have now become a complete farce'.[48]

Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations

3.43

The Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations

(ANZSCO) framework is 'a skill-based system used to classify occupations and

jobs in the Australian and New Zealand labour markets'. It was developed by the

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistics New Zealand and the then Australian

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, and first released in 2006.[49] The ANZSCO was the subject of a significant review in 2009, with a further

review occurring in 2013.[50]

3.44

ANZSCO is used for various purposes, including providing the

definitional categories for occupations on the skilled migration lists. The

ANZSCO framework outlines job titles, a description of the job, qualifications

indicative for the skill level of an occupation, and typical tasks involved.

For example, the following information is included for chefs:

- The ANZSCO unit group code of 3513 (Chefs), with a specific

ANZSCO code 351311 for the occupation of chef.

- A description of what a chef does—that is, plans and organises

the preparation and cooking of food in dining and catering establishments.

- The occupation's skill level and qualification level expected for

someone employed as a chef (skill level 2, with an Associate Degree, Advanced

Diploma or Diploma, or at least three years of relevant experience).

- A list of typical tasks of a chef, include planning menus, estimating

food and labour costs, monitoring quality of dishes at all stages of

preparation, demonstrating techniques and advising on cooking procedures, and

explaining and enforcing hygiene regulations.[51]

3.45

The Department of Home Affairs uses ANZSCO requirements for occupations

when assessing the skills and experience of skilled visa applicants.[52]

Issues with the ANZSCO framework

3.46

Significant concerns were expressed by a range of stakeholders about

perceived shortcomings in the ANZSCO framework, including that the framework

has not kept pace with modern workforce trends and is in urgent need of

revision.[53] The Migration Institute of Australia argued in its submission:

The skilled occupation lists, skills assessment regimes and

the Department's skilled application processes are all inescapably tied to the

minutiae of the ANZSCO occupational descriptors. However, the current five year

intervals between ANZSCO updates, reduces its ability to capture rapidly

developing occupational changes and impairs its effectiveness as a tool for

identifying changing occupational trends and developing skills shortages.[54]

3.47

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry called for an urgent and

comprehensive review of the ANZSCO:

Despite major changes to the economy and jobs including new jobs

driven by technology as well as changes to the level of skill needed in certain

jobs, ANZSCO has only been reviewed and revised twice...since its introduction in

2006... A major review of ANZSCO is long overdue. Occupations in ANZSCO are out

of date in that skill levels are not reflective of the current work performed

and for many industries it is woefully inadequate in assessing the skill needs

in the context of new occupations.[55]

3.48

Universities Australia used an example from its sector to highlight the

shortcomings of the current ANZSCO framework:

Universities Australia is...concerned about other

university-based occupations which do not feature on the [ANZSCO] but are of

vital importance to the long-term success of Australia's universities. Of

particular importance are university advancement and philanthropy professionals

where the recruitment of foreign expertise is vital in fostering the

development of philanthropy capability in Australian universities. The lack of

a specific category for such an important profession highlights the current

disconnect between the ANZSCO and the ever-evolving university sector.

Assigning a new occupation to the ANZSCO is a complicated administrative

process with long time lines. Furthermore, submitting an occupation for inclusion

on the ANZSCO may not result in a positive outcome after many months of

consideration, nor does a final inclusion on the ANZSCO immediately result in

the occupation being listed on the Skilled Occupation List. It raises the issue

of whether an alternate approach to classifying occupations is required which

is more responsive to the changing nature of the workplace.[56]

Views of government agencies

3.49

The Joint Departmental Submission argued that the ANZSCO framework is

'flexible in capturing the vast majority of occupations' and 'covers many

alternative and emerging job titles' besides those that appear in the

legislative instruments that give effect to the skilled occupation lists.[57]

3.50

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) commented that classifications

such as the ANZSCO 'should be reviewed ten yearly to remain relevant', and

noted that reviews to the ANZSCO occurred in 2009 and 2013.[58]

3.51

The ABS explained that in 2017–18 it consulted widely and confirmed

broad stakeholder support for a review of the ANZSCO; however, the review did

not proceed due to a lack of funding and the need to prioritise the ABS' core

statistics program.[59]

3.52

The ABS noted further that in the absence of a full ANZSCO review, the

ABS and Statistics New Zealand have recently agreed to jointly undertake

maintenance work of the ANZSCO skill levels:

This work will support relevant agencies to apply ANZSCO to

administer skilled migration policies and continue to make sure that people

receiving skilled migration visas have the right level of skills for the right

occupation.

The maintenance of the ANZSCO skill levels is limited to

updating the skill level definitions of existing occupations within ANZSCO. It

will not result in the addition, deletion or movement of any categories or

codes within ANZSCO. This makes the work to maintain the skill levels a less

resource intensive undertaking [than] a review.[60]

Skills assessments regime

3.53

Particular skills assessing authorities carry out assessments of

temporary skilled visa applicants to ensure that their skills meet the

requirements of occupations in Australia. The Department of Education and

Training manages the skilled migration assessing authorities.[61] The assessments carried out by these approved bodies then inform the decisions

the Department of Home Affairs makes on skilled migration.[62] Where required, visa

applicants for TSS visas must provide a completed skills assessment when

applying, or evidence that a skills assessment has commenced.[63]

3.54

For example, Trades Recognition Australia, a skills assessment service

provider within the Department of Education and Training, provides skills

assessments for people with trade skills for the purpose of migration. It

engages approved organisations to carry out parts of the TSS Skills Assessment

Program on its behalf.[64]

3.55

State and territory governments, through Overseas Qualifications Units,

also conduct assessments of overseas qualifications for general purposes.[65]

3.56

Occupations for the skilled migration program more broadly that have

mandatory skills assessments are outlined in delegated legislation, along with

the relevant ANZSCO codes for these occupations.[66] The relevant skills assessment authorities that have been designated for

particular occupations are outlined in a legislative instrument.[67] The requirement to undergo a skills assessment for some occupations differs

depending on an applicant's country of origin.[68]

3.57

Skills assessments may take place in Australia, based on the relevance

of an applicant's qualifications, training and work experience, or offshore,

with the assessing authority travelling to conduct an interview and/or a

practical skills assessment with the applicant.[69]

3.58

Key concerns that submitters and witnesses outlined about the current

skills assessment regime included the following:

- the stringency of the current skills assessment regime;

- the length of the skills assessment process;

- overreliance on ANZSCO codes in skills assessments;

- limited recognition of previous employment experience; and

- different skills assessment requirements based on nationality.

Stringency of skills assessment regime

3.59

The committee received conflicting evidence about the skills assessment

regime, with a number of submitters and witnesses arguing that stricter

requirements are needed, and some others arguing that the system is already too

onerous.

General concerns that the skills

assessment regime is too onerous

3.60

The Migration Institute of Australia argued that the skills assessing

regime is 'extremely difficult to navigate, slow and costly for consumers'.[70] It proposed that requirements for skills assessment be reduced to those

necessary to protect consumers and the public.[71] Similarly, a Joint University submission suggested that the requirement for

skills assessments was 'onerous, expensive and unnecessary' for the university

sector, contending that universities were best placed to determine whether an

individual has the necessary skills and work experience.[72]

3.61

Business SA questioned why skills assessments are a requirement for visa

applicants even if the applicant has completed their vocational or tertiary

education in Australia.[73]

Concerns about inadequacies in the

skills assessment regime

3.62

In contrast, other submitters were of the opinion that the skills

assessment regime needs to be strengthened. The Australian Council of Trade

Unions (ACTU) expressed concerns that when it had raised the issue of

maintaining occupational licencing standards with the Australian Government,

such as in the context of free trade agreements, the response had been that

visa applicants would 'be required to demonstrate to the [Department of Home

Affairs] that they possess the requisite skills and experience' to work in Australia.

As a result, the ACTU suggested, decisions on skills assessments 'are being

vetted by the [Department of Home Affairs] with little more than a paperwork

inspection'. They contended:

This is leading to situations where there is no guarantee

that temporary workers will have the same level of skills, health and safety

knowledge and qualifications as are required for local workers, potentially

endangering themselves, other workers and the public.[74]

3.63

The ETU echoed these concerns, suggesting that in such circumstances the

Department of Home Affairs and employers had carried out no genuine assessments

of applicants' skills and qualifications.[75]

3.64

The Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU)

also raised concerns about international trade agreements removing 'mandatory

skills assessments for overseas workers in a range of trades'.[76]

3.65

The ACTU proposed that skills assessment processes 'must be

significantly strengthened' by:

- ensuring all testing is performed by an appropriate industry body

and not by immigration officials;

- guaranteeing that workers who currently require an occupational

license must successfully complete a skills and technical assessment undertaken

by a Registered Training Organisation approved by Trades Recognition Australia

before being granted a visa;

- introducing a risk based approach to assess and verify workers

are appropriately skilled in occupations that do not require an occupational

licence; and

- introducing a minimum sampling rate of visas issued in order to

verify that migrant workers are actually performing the work the employer has

sponsored them to perform.[77]

3.66

Specialist management consultancy firm Cross Cultural Communication and

Management called for increased strengthening of the skills assessment regime,

proposing that all trade occupations should have mandatory skills assessments,

and that assessing authorities be permitted to conduct skills assessments in

whichever countries they consider to be appropriate for commercial reasons.[78]

3.67

Other evidence also supported increased requirements for skills

assessments in particular industries. For example, the Australian Association

of Social Workers stated that skills assessments are not required of every visa

applicant:

...only some TSS visa applicants must undergo a mandatory skills

assessment as part of the visa application process. For the occupation of

social worker, a qualification skills assessment is not required of the

prospective employee. For example, the position of Advanced Child Protection

Worker does not require this, despite widespread professional recognition that

a social work qualification is the most appropriate minimum standard.[79]

Length of skills assessment process

3.68

Some evidence raised concerns about how long it takes for a skills

assessment to be completed, particularly in the context of other, sometimes

lengthy application requirements.[80] For example, the Migration Institute of Australia stated:

It is not uncommon for skills assessing authorities to

require a large quantity of evidence and to take in excess of 3 months to

assess an applicant's skills. When added to the extended temporary skills visa

processing times by the Department, in effect it may take six months to

on-board a suitable visa holder.[81]

3.69

Business SA argued that 'skills testing adds delays to the visa

application process... [T]he skills assessment process is stringent and

exhausting'.[82]

Overreliance on ANZSCO codes when

conducting skills assessments

3.70

Several issues were raised regarding the intersection between the ANZSCO

codes for occupations on the skilled occupation lists, and the processes for

undertaking skills assessments for those occupations.

3.71

RDA Far South Coast contended that the skills required for particular

occupations in some existing ANZSCO codes were either 'not identified at all or...inadequately

listed'.[83] The Migration Institute of Australia submitted that without 'a descriptor that

lists the common skills and tasks associated with these occupations, there is

no skills assessment process and often no skills assessing authority'. As a

result, the Migration Institute argued, some occupations on the skills lists

were effectively 'unusable for employers seeking to sponsor skilled workers'.[84]

3.72

The Migration Institute also expressed concern that skills assessing

authorities may be 'rigidly' applying ANZSCO descriptors when assessing an

applicant's skills, despite caveats in the introduction to the ANZSCO framework

that the descriptions should be used as a guide and not prescriptively.[85]

3.73

The Law Council suggested that there may be instances where the duties

of a position cross several different ANZSCO codes, meaning that they do not

fit the skills assessment requirements of any occupation:

For example, a sales and marketing manager... who is... on a

salary of over $250,000 is in a senior management role in a large multinational

company, who reports directly to the Chief Marketing Officer. The ANZSCO

requirement is that the manager must hold a bachelor degree or five years of

relevant work experience. However, the requirement of Australian Institute of

Management (the assessing body for managers) to obtain the relevant skill

assessment is that the manager's role must report directly to the CEO and that

the role has three subordinate management level positions. Despite the fact

that the business is not structured in this way, a skills assessment would be

refused.[86]

Limited recognition of previous

employment experience

3.74

The Migration Institute of Australia submitted that some assessing

authorities do not recognise employment experience in lieu of formal

qualifications. This had led, it suggested, to a skills assessment system that

concentrated on formal qualifications, 'when in many cases what employers are

looking for is workers who are skilled on the job, not on paper'. The Migration

Institute noted that recognition of prior learning had to some extent led to

progress in the recognition of prior skills and experience, but 'these

processes can take in excess of twelve months to complete, before the formal

skills assessment process can even be commenced'.[87]

3.75

The Law Council of Australia also raised the issue of skills assessments

not recognising applicants who may have decades of work experience but no

qualifications, particularly if they are aged over 45.[88] Dr Carina Ford, the Deputy Chair of the Migration Law Committee at the Law

Council of Australia, argued that 'for TSS applicants a skill assessment should

not be required where an applicant has demonstrated a substantial number of

years of work experience in their occupation'.[89]

Different skills assessment

requirements based on nationality

3.76

Cross Cultural Communications and Management explained that the approach

taken to skills assessments can vary depending on the country of origin of the

applicant, and proposed that skills assessments by assessing authorities should

be required of all vocational trades, regardless of the applicant's

nationality. It submitted that 'employers would prefer that all skilled workers

for the occupation, irrespective of source country, are treated equally and are

required to undergo skills assessments'. This, it suggested, would provide

'employers a degree of comfort' about the skills of their candidate.[90]

Committee view

3.77

The issues raised in this chapter address various components in the

machinery of the temporary skilled visa system, including:

- the methodology used by the government to determine the presence

of skills shortages;

- the process for revising the composition of the skilled migration

occupation lists;

- the structure and relevance of the Australian and New Zealand

Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO); and

- processes for assessing the skills of overseas workers applying

for temporary skilled visas.

Process for implementing changes to

the skilled occupation lists

3.78

The committee is concerned by evidence received during the inquiry that various

occupations included in the skilled migration occupation lists do not, in fact,

appear to be suffering from a shortage of appropriately skilled Australian citizens

and permanent residents.

3.79

Given that the stated purpose of the TSS visa is to fill critical skills

shortages and ensure that Australian workers are given the first priority for

jobs, the primary basis for occupations being included on the occupation lists

must be empirical evidence demonstrating a genuine labour market shortage that

cannot be resolved through increasing wages or training Australian workers.

3.80

Similarly, if the TSS visa is intended to provide businesses with

temporary access to the critical skills they need to grow if skilled

Australians workers are not available, it should follow that decisions made on

the composition of the lists should reassure all stakeholders that their input

and concerns have been taken into account. This includes both the union sector,

which is often best placed to provide on‑the‑ground evidence on

whether a reported skills shortage is genuine or not, and industry, which will

suffer adversely if it is unable to fill critical vacancies. At present, this

does not appear to be the case.

3.81

There is a near total lack of transparency around how final decisions

are made on changes to the skilled occupation lists. The advice provided by the

Department of Jobs and Small Business following stakeholder consultations to

the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs is not

published, and there is very little visibility on how that advice is turned

into the final decisions announced by the Minister. Recent changes to the

skilled migration occupation lists have been announced with very limited detail

as to why certain occupations have been included (or not included),

leading to doubt across different sectors that the decisions are anything but

arbitrary or subject to ministerial or departmental whims. These concerns could

be addressed if the reasons for the inclusion of particular occupations were

published.

3.82

As such, the committee considers that future updates to the skilled

occupation lists should outline the reasons for including new or removing

particular occupations, or for moving occupations between the Short Term

Skilled Occupation List, the Medium and Long Term Strategic Skills List, and

the Regional Occupation List.

Recommendation 4

3.83

The committee recommends that the Australian Government publish, in

future updates to the skilled migration occupation lists, its reasons for

including new occupations, moving occupations between the different lists, or

removing occupations altogether that were included in previous iterations of

the lists.

3.84

The committee also heard that there is considerable uncertainty about when

updates to the occupation lists will be published. For example, updates

occurred in July 2017, January 2018, March 2018 and March 2019, with the most

recent update occurring almost 12 months since the Department of Jobs and Small

Business first commenced a review.[91]

3.85

The committee considers that this lack of consistency in relation to the

timing of updates has led to uncertainty and further impacted stakeholder

confidence in the robustness of the process. The Australian Government should

recommit to a regular timeframe for when updates will be released, and publish

this information to provide certainty and clarity.

3.86

The committee further recognises the concerns raised in evidence that

the occupation lists are overly complex and confusing for anyone but migration

agents. The committee proposes that the Australian Government should take these

concerns into account when making any future changes to the occupation lists.

The Australian and New Zealand

Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO)

3.87

It is not clear to the committee why the Australian Government is

relying on an ANZSCO framework that stakeholders have universally described as

outdated. The most recent review to the ANZSCO list occurred six years

ago. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) explained to the committee that

it had been unable to proceed with a review following consultation in 2017–18

on the need for a review because of funding priorities. The ABS further

outlined that its maintenance of the lists will be restricted to updating skill

level definitions of existing occupations. However, new occupations regularly

emerge and the tasks and ways in which jobs are undertaken are subject to

constant change.

3.88

Given the importance of the ANZSCO framework to aspects of the temporary

skilled migration system, including skills assessments and the occupations

included in the skilled migration occupation lists, the committee considers

that a review to the ANZSCO framework is long overdue. 'Maintenance' of the

ANZSCO framework is not sufficient to ensure that the temporary skilled

migration program is responding to genuine skills shortages or that skills

assessments are based on job duties that remain relevant. The Australian

Government should sufficiently fund the Australian Bureau of Statistics so that

it is able to conduct a review of the ANZSCO framework.

Recommendation 5

3.89

The committee recommends that the Australian Bureau of Statistics

prioritise its review of the ANZSCO framework.

Skills assessments processes

3.90

The committee notes the concerns of various submitters and witnesses

about deficiencies in the current skills assessment process. In particular, the

committee is concerned that in some instances the requirements for a skills

assessment may be limited to no more than a paperwork check by the Department

of Home Affairs. The committee considers that training and licensing

obligations must be maintained for all skilled trades, with skills testing

required for other industries and professions as necessary. Measures to

strengthen the skills assessment regime are required in order to ensure that Australians

can have confidence in the work being undertaken by temporary skilled visa

holders.

Recommendation 6

3.91

The committee recommends that the current skills assessment regime for

the skilled visa system be strengthened by:

- ensuring all testing is performed by an appropriate industry body

and not by immigration officials;

- guaranteeing that workers who currently require an occupational

license must successfully complete a skills and technical assessment undertaken

by a Registered Training Organisation approved by Trades Recognition Australia

before being granted a visa;

- introducing a risk based approach to assess and verify that workers

are appropriately skilled for occupations that do not require an occupational

licence; and

- introducing a minimum sampling rate of visas issued in order to

verify that migrant workers are actually performing the work the employer has

sponsored them to perform.

Need for an independent authority

on skilled migration issues

3.92

More fundamentally, the committee considers that the processes for

determining skills shortages, reviewing skilled migration occupation lists, and

guiding other aspects of the temporary skilled visa system could be improved by

the establishment of an independent authority to provide advice and

recommendations to the Australian Government on skilled migration issues. This

independent authority could be constituted as a tripartite body with equal

representation from government, union and employer groups.

3.93

Such a tripartite body was recommended by the Azarias Review in 2014.

The review identified the need to provide a more robust evidence-based approach

to improving the transparency and responsiveness of the skilled occupation

list, and suggested that a new tripartite ministerial advisory council

supported by a dedicated labour market analysis resource could fulfil this

function.[92]

3.94

The committee considers that the functions of a proposed independent

authority on skilled migration could include:

- ensuring skilled migration programs provide a benefit to

Australia and reflect local labour market needs;

- regularly reviewing a single skills shortage list to add or

remove occupations in response to changes in Australia's skills, job market and

regional employment conditions;

- providing advice to the Australian Government about current

skills shortages and skill bottle-necks, and identifying circumstances

preventing local workers from meeting Australia's skills needs;

- projecting Australia's future skills shortage and making

recommendations about how to prevent these skills shortages from occurring; and

- reviewing the level of the Temporary Skilled Migrant Income Threshold

on an ongoing basis and making recommendations on the Market Salary Rate

Framework (see Chapter 2).

3.95

As noted above, the proposed independent authority would need to be

supported by a dedicated independent labour market analysis resource. The

authority could also play a role in liaising with state and local governments

to ensure that regional skills shortages and training initiatives are aligned.

Recommendation 7

3.96

The committee recommends that the Australian Government consider the

establishment of a new independent tripartite authority to provide advice and

recommendations to government on skilled migration issues.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page