Chapter 5

Barriers to accessing mental health services

Introduction

5.1

This chapter considers the barriers to accessing mental health services

for ADF members and veterans, primarily their reluctance to seek help. It also

focuses on the difficulties and challenges experienced by ADF members and

veterans in seeking assistance through Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA)

delivery models and claims processes, including ADF members and veterans who

live in regional and remote areas.

Stigma and perceived barriers to care

ADF members

5.2

As discussed in previous chapters, both Defence and DVA agree that early

identification and treatment of mental ill-health is essential for achieving

the best outcomes for ADF members and veterans with mental ill-health. However,

the 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and Wellbeing Study (MHPW study) found

that 'a significant number of personnel with mental disorders had received no

care in the previous 12 months'.[1]

The MHWP study found potential stigma to be a 'substantial issue', which

limited the probability that ADF members would seek treatment for mental

ill-health,[2]

explaining that:

Research indicates that two main factors contribute to the

low uptake of mental health care: the fear of stigma and perceived barriers to

care. Stigma is a negative attitude resulting from the acceptance and

internalisation of 'prejudice or negative stereotyping', while barriers to care

are the organisational, procedural or administrative aspects of access to

mental health care that may preclude or reduce access to mental health

treatment and support. Barriers may include issues associated with

confidentiality, anonymity and confidence in the mental health service

providers. These are influenced to varying degrees by internalised stigmas

about access to care and the consequences of asking for help.[3]

5.3

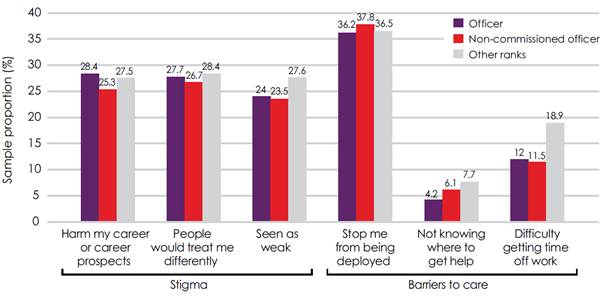

The MHWP study found that among its respondents, the highest rated

barrier to personnel seeking help for a 'stress-related, emotional, mental

health or family problem' in the ADF was the concern that seeking help would

reduce their deployability (36.9 per cent). The highest perceived stigma that

concerned members was that people would treat them differently (27.6 per cent)

and that seeking care would harm their careers (26.9 per cent). The findings

are outlined in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 – Estimated prevalence

of stigma and barriers to care, by rank

Department of Defence, Mental

Health in the Australian Defence Force: 2010 ADF Mental Health Prevalence and

Wellbeing Study Report, p. xxix.

5.4

A significant number of submissions also identified stigma surrounding

mental ill-health and perceived barriers to care as key factors limiting the

likelihood that ADF members would seek treatment for mental ill-health.[4]

A study investigating PTSD and stigma in the Australian Army, conducted by John

Bale for the Army in 2014, reported on Australian soldiers' experiences of stigma

due to mental ill-health. One solider commented:

After my break down and subsequent hospitalisation words

cannot express how lost I felt, the confusion and most of all the feeling of

despair. My Chain of command had no idea how to engage me and my unit turned

its back on me. Life was hard enough, but it was made harder that I had served

18 years and was not farewelled from my unit, mess, or Corps. It was not until

then that I realised that the stigma surrounding mental health and especially

PTSD within the Army was widespread.[5]

5.5

Another example told of a soldier being accused of malingering and his

concerns being dismissed when asking for mental health support and assistance from

members of his chain of command:

When first asking for assistance for mental health support

from within my immediate chain of command [sergeant and warrant officer class

2] I was met with an attitude that I was malingering and the immediate

questioning of my integrity as a JNCO.

I pursued the matter outside my chain of command, although

still within my unit, and a meeting with the unit RSM was arranged. I raised my

concerns about my mental health and wellbeing and was told to 'harden the f**k

up' and to get on with my job.[6]

5.6

The committee received similar evidence from ADF members and veterans

who told the committee that if ADF members raise concerns regarding mental

ill-health they are often dismissed or accused of malingering.[7]

Mr Matthew McKeever, a veteran, told the committee of his experiences, asserting

that ADF members who are struggling with mental ill-health, or even physically

injured, are commonly ostracised and called 'lingers':

As soon as they find out that you have a mental illness or

any kind of illness, regardless of whether it is a knee, back or whatever, you

are treated as a malingerer and you are treated quite badly. They do not want

to acknowledge you; they want to kick you out as soon as possible.[8]

You want to ask for help, but you know what the reaction is

going to be. I was a platoon sergeant. I used to sit in on med boards. I know

exactly what goes on in them. The words that are thrown around are, 'He's weak.

He is a linger. Let's just kick him out.' I have seen it firsthand because, as

a platoon sergeant, I am part of that criteria. I would quite often be spoken

down to because I would stand up for the soldier and say, 'No, that's not

right. He's got a serious injury.'

I had a soldier who, at 21, had a hip replacement. They just

booted him out of the army as a linger. That is not acceptable. They go on

about mateship, courage and initiative. Yes, courage and initiative is what you

have. Where does the mateship come into it? It does not.[9]

5.7

Dr Niall McLaren pointed to ADF cultural views of strength as a

significant contributing factor to the stigma surrounding mental ill-health:

Compounded in all of this is the intense stigma directed

against people with mental problems in the Defence forces, and this stems from

the myth of the 'real man'. The myth of the 'real man' is that there is no such

thing as pain, sickness or mental disorder, only weakness of will. Anybody who

shows pain, sickness or mental symptoms—and this is continuing with the myth—is

weak and must be treated harshly until he gets tough 'like us'. That myth is

absolutely rife. It is everywhere. It is in the air that people breathe in the

Defence forces. Of course, it is fantasy.[10]

5.8

The Chief of the Defence Force (CDF), Air Chief Mark Binskin, acknowledged

that stigma regarding mental ill-health is 'one of the biggest challenges we

continue to face in the Australian Defence Force'.[11]

However, when asked by the committee, the CDF disagreed with the allegations

that Defence had a cultural problem regarding members seeking assistance when

struggling with mental ill-health being ostracised and accused of malingering,

responding that 'No, I think that we have had issues in the past and I am sure

that there are pockets there now, still, that we will have to work on from a

cultural point of view for people to understand that this is a command issue in

looking to rehabilitate our people'.[12]

5.9

Defence assured the committee that it has introduced a range of

educational resources and activities to reduce stigma surrounding mental

ill-health:

...board developments and achievements since 2009

include...mental health education resources and activities such as the annual ADF

Mental Health Day to reduce stigma and barriers to care by increasing awareness

of mental health issues and understanding of PTSD, depression, suicide

prevention and alcohol misuse and how to seek help as early as possible.[13]

5.10

In the ADF Mental Health & Wellbeing Plan 2012-2015 (MHWP), Strategic

Objective 1 is 'to promote and support mental health fitness in the ADF' and

aims for:

-

a culture that promotes wellbeing and reduces the stigma and

barriers to mental health care;

-

ADF personnel who are mental health literate and know when, how,

and where to seek care for themselves and their peers; and

-

selection, training, and command systems that promote good mental

health and wellbeing.[14]

Impact of mental ill-health on

deployment and career

5.11

The MHWP study found that among its respondents, the highest rated

barrier to personnel seeking help for a 'stress-related, emotional, mental

health or family problem' in the ADF was the concern that seeking help would

reduce their deployability (36.9 per cent) and that seeking care would harm

their careers (26.9 per cent). This was also reflected in the evidence received

by the committee.[15]

5.12

Walking Wounded told the committee that the medical classification

system, and in particular, the requirement that Army personnel be able and

ready to deploy, reinforces and confirms ADF members' concerns that their

deployability is inextricably linked to their employability:

Most soldiers are honest but most soldiers are realists too.

Some years ago, when they changed the medical classification system in Army so

that you could no longer serve if you had an injury that prevented you from

serving overseas, that cut out a whole bunch of people who were very useful in

Army. Just because they could not deploy did not mean they

could not do good work elsewhere. I served many years ago with a major at

Kapooka, and it was not until I saw him running in PT gear that I realised he

only had one leg. He lost a leg in Vietnam thanks to a mine but he had

served—and this was 20 years after the end of Vietnam—quite happily with a

wooden leg. I thought: why not? Why would you want to lose that experience if

that person can still provide that service? We are not going to send him

overseas to fight again but, gee, there are lots of good jobs he could do in

Army otherwise.

Probably the greatest problem now is that the medical

classification system means that, if you are not ready to deploy, you cannot

continue employment in the Army. For a lot of young men and women that means

that they are losing the job they have always wanted. That is something that

needs to be addressed. When you are in uniform, you need that understanding

that the organisation is going to look after you, that it is going to keep you

on board and you have got that reassurance. Certainly when I was a digger that

was the case—you knew that you would certainly not be losing a job because you

had suffered a bad injury that you might not get back from. That is not the

case these days, of course.[16]

5.13

The Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL) stated that many ADF

members fear the impact that disclosing mental ill-health will have on their

ability to support their family:

Given a relative lack of civilian qualifications, many

servicemen/women (with mortgages and young families) fear the impact that

disclosing psychological injury will have on their ongoing employability,

deployability, promotional opportunities and therefore their incomes.[17]

5.14

Mr Mark Keynes told the committee:

Probably the biggest problem is the stigma associated with

seeking help. Many troops believe that anyone who asks for help is unlikely to

deploy and will probably be medically discharged. Many believe that asking for

help can be a career ending move, hence the stigma.[18]

5.15

Mr John Bale, in his report regarding PTSD and Stigma in the Australian

Army, highlighted ADF members' fears of being discharged as a key factor in

their reluctance to seek treatment for mental ill-health, especially for ADF

members of lower rank:

Job security is vital to soldiers. Soldiering is key to the

perceived self-worth of many who serve, and termination of employment by the

Army is a dramatic and often confronting experience and one that soldiers will

do almost anything to avoid. The fear of being discharged due to the disclosure

of PTSD is currently a significant barrier to care, and a promise made by the

senior leadership of the ADF and the Australian Army does little to reassure

the lower ranks of the Army who are among those most affected by PTSD.[19]

5.16

To allay these fears, Mr Bale called for the ADF to highlight positive

experiences from currently serving ADF members who have undergone

rehabilitation for mental ill-health and have successfully returned to their

career. Mr Bale also noted that this will also encourage ADF members to seek

treatment early, to improve their chances of successful rehabilitation:

The most effective way to allay fears over job security for

those who seek treatment for PTSD is to highlight positive experiences from

currently serving soldiers who have been rehabilitated and subsequently enjoyed

successful careers. These soldiers' stories, highlighting their successful

return to an Army career, present a highly effective means of reassuring those

with PTSD that they will only be medically discharged if they cannot be

successfully rehabilitated. This message can also be useful in reinforcing the

need for early intervention, signalling the fact that the sooner individual

sufferers seek help, the greater the chance of their recovery, and the less

likely they are to face discharge.[20]

5.17

Defence emphasised its commitment to rehabilitation, informing the

committee that of the 869 individuals with a mental illness who completed a

rehabilitation program in the period from July 2013 to June 2014 a total of 420

(or 52 per cent) are recorded as having a successful return to work at the end

of their rehabilitation program. Defence provided three recent examples of ADF

members of differing ranks that completed a rehabilitation program following referral

for mental illness:

The first example involves an officer who was diagnosed with

PTSD following an operational deployment in 2011. The officer’s health care and

rehabilitation program included a six week PTSD program. The officer was

successfully returned to work in his current unit. As at October 2015, it is

reported that the officer remains well supported by his unit and colleagues,

and his ongoing prognosis and needs are being monitored by his health care

team.

The second example involves a Senior Non Commissioned Officer

(SNCO) who was medically downgraded because of both physical and mental health

conditions related to multiple deployments. During 2014, the SNCO was provided

with clinical treatment and health care, and referred to the ADF Rehabilitation

Program. With the support of the rehabilitation consultant, commanding officer

and health care team, the SNCO remained in the unit and was given the time to

recover and achieve a full return to work outcome. The SNCO was medically

upgraded in mid 2015, is undertaking a military course and will potentially be

posted and deployed again in 2016.

The third example involves a junior ranked soldier with

specialist skills who witnessed deaths during multiple deployments, resulting

in a mental health condition. This member was provided with health care and

referred for rehabilitation during 2013. The rehabilitation was successful,

with the member being medically upgraded, promoted to a Non Commissioned

Officer (NCO), and deployed on operation again in 2014.[21]

5.18

The RSL also commended the ADF, noting the 'great step forward' of

providing a mandatory two-year period of treatment, rehabilitation and/or

vocational training for ADF members allowing members to adapt their career

plans:

The ADF's recent initiative of giving their employees a

mandatory 2 year period of treatment/rehabilitation/vocational training (either

back into ADF employment or in the civilian world) once a significant injury is

identified is a great step forward.[22]

5.19

Defence developed a 30-minute documentary, Dents in the Soul–helping

to cope with PTSD, which is available from the Defence Health portal

website. The documentary aims to 'de-stigmatise PTSD and to show that it can

potentially happen to anyone'. It acknowledges ADF members' fears of stigma and

condemns attitudes that mental ill-health is 'weakness'. The documentary calls

for 'psychological sentry duty' asserting that commanders and fellow ADF

members have a duty to look out for and to help anyone struggling with mental

ill-health and declaring that those who do not have failed their subordinates

or their mates.[23]

The documentary features interviews with current ADF members who have undergone

successful rehabilitation for PTSD and returned to work, emphasising that

'recovery rates from PTSD are high but early diagnosis and treatment are

particularly important'. It strongly and repeatedly emphasises that Defence has

invested in and values ADF members and states its desire to rehabilitate and

retain its members.[24]

5.20

Aspen Medical reported that 42 per cent of its clinicians agreed or

strongly agreed with the statement that there is increasing awareness and

acceptance of mental health issues and PTSD amongst Defence personnel which is

reducing the stigma formerly attached to mental health issues, with 21 per cent

disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Aspen Medical commented that 'this

suggests that attitudes are changing within the ADF and that the efforts of the

ADF and JHC have met with some success', as well as noting that 'it is also

clear that this cultural shift will take more time to become fully embedded

within the ADF'.[25]

Department of Veterans' Affairs claims processes

5.21

DVA is responsible for a range of programs providing 'care,

compensation, income support, and commemoration for the veteran and defence

force communities and their families'. DVA administers three key pieces of

legislation which governs veterans access to care and support entitlements:

-

Veterans Entitlements Act 1986 (VEA), which provides

compensation, income support, and health services for those current and former

members of the ADF who have rendered services in wars, conflicts, peacekeeping

operations, and certain other deployments before 30 June 2004. Current and

former ADF members with peacetime service between 1972 and 1994 and some

veterans with warlike service and non-warlike service after 1 July 2004 may

also have access to certain VEA entitlements;

-

Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988 (SRCA),

which is workers' compensation legislation that applied to members and former

members of the ADF, Reservists, Cadets, and Cadet Instructors and certain other

persons who hold an honorary rank in the ADF, as well as members of certain

philanthropic organisations that provide services to the ADF; and

-

Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2004 (MRCA),

which provides compensation and rehabilitation for current and former members

of the ADF as well as Cadets, Cadet Officers, and Instructors whose injury or

disease is caused by service on or after 1 July 2004. The MRCA superseded the

SRCA at this date for DVA, as well as most of the provisions contained within

the VEA.[26]

5.22

There are two ways that veterans can apply to DVA for assistance with

mental health conditions:

-

the non-liability pathway: for certain mental health conditions

whatever the cause, to receive treatment only; and

-

the liability pathway: for mental health conditions related to

service in the ADF, to receive compensation and treatment.[27]

Non-liability pathway

5.23

In 2013, DVA approved 1,244 non-liability applications for mental health

and in 2014, approved 3,826.[28]

DVA advised the committee that the eligibility requirements for non-liability

mental health service provision were expanded in 2014 and again in 2015.

Non-liability mental health services are now available to anyone who has

deployed on operations overseas or has completed three or more years of

continuous service in peacetime since 1972.[29]

5.24

Under the new arrangements, DVA can pay for treatment for diagnosed

PTSD, anxiety, depression, alcohol use disorder, or substance use disorder

whatever the cause. Furthermore, DVA can now accept diagnosis from vocationally

registered GPs, clinical psychologists, or psychiatrists. If a person has been

diagnosed with one or more of these conditions, they are issued with a White

Treatment Card (White Card), which provides access to treatment such as GP

care; specialist care in the community, such as from a psychologist or

psychiatrist; and hospital care.[30]

5.25

A number of submissions supported non-liability mental health service

provision and called for eligibility to be broadened further.[31]

The RSL described the provision of non-liability support as 'invaluable' but

called for eligibility to be extended to everyone who has served in the ADF:

DVA's non-liability mental health support for eligible

veterans has proved to be invaluable for the veterans who often present to an

RSL Pension Officer at breaking point. This allows them to immediately access

specialist health while their DVA claim is processed. The RSL

would support the extension of non-liability mental health support to all who

have served in the ADF.[32]

Liability pathway

5.26

A serving or ex-serving ADF member who has a medical condition,

including mental health conditions, for reasons related to their service, can

make a liability claim. Once the liability claim has been accepted, DVA can

provide services such as rehabilitation (including vocational assistance),

medical treatment, (such as White or Gold Treatment Cards), attendant care, household

services, and a range of other benefits. Compensation may also be provided for

an inability or reduced ability to work or to recognise the effects of a

permanent impairment resulting from a service-related incident.[33]

5.27

DVA assesses claims to determine whether the injury, illness, or disease

is related to the claimant's service, with most claims being assessed under the

VEA, SRCA or MRCA, depending on which piece of legislation applies to the

claimant. Claims processed under the VEA or MRCA are assessed using Statements

of Principles, which list factors that 'must' or 'must as a minimum' exist to

cause a particular kind of disease, injury or death and which could be related

to military service. The Statements of Principles are determined by the Repatriation

Medical Authority, which consists of a panel of practitioners eminent in fields

of medical science. Claims processed under the SRCA are assessed 'using

available medical evidence to support consideration of a disease, injury, or

illness'.[34]

Impact of claims processes on

mental health of claimants and their families

5.28

The committee received considerable evidence regarding the difficulties

that many veterans, especially those struggling with mental ill-health, have

when seeking assistance from DVA, and the detrimental impact that the claims

process can have on their mental health.[35]

The RSL told the committee that 'the DVA Compensation process complicates,

aggravates and perpetuates the pre-existing psychological distress suffered by

veterans and their families'.[36]

5.29

Slater & Gordon Lawyers described the DVA claims process as

'combative' noting that its clients' experiences with the DVA claims process

are detrimental to their already compromised mental health:

We are witnessing Veterans being drawn into a system of

combative legislation with a bureaucracy of Departments shifting

responsibility. My team can attest to the voices of other Veterans advocates

and ex-service organisations that lodging claims with the DVA for compensation

and treatment of physical and mental issues is "like going through a meat

grinder, it grinds you up".[37]

5.30

Soldier On highlighted the confusing and overwhelming nature of the DVA

claims processes, noting that it 'routinely aggravates existing mental health

conditions':

The process of navigating a claims process routinely

aggravates existing mental health concerns in many people attempting to access

support from DVA. One partner of a veteran said they weren't in a position to

sit down and manage their way through the confusing mix of support available.

She described it as looking at the night sky. "There are many bright,

shiny places to go, but out of the hundreds of options, where are we meant to

go? What we need is a map, we don't need more stars."[38]

5.31

Mrs Catherine Lawler, the wife of a veteran struggling with mental

ill-health, told the committee that the claims process can be overwhelming for

both veterans and their families. Mrs Lawler noted that the 'torturous and

arduous' claims process results in many veterans giving up on their claim:

...lodging a claim with DVA may seem to be a reasonable

straight forward process, but the legal aspects under consideration are

complex, potentially involving multiple pieces of legislation, the

administrative requirements exacting, and the time frames very lengthy. And the

veteran is expected to deal with all of this while living with the debilitating

effects of PTSD or mental illness.

It is a torturous and arduous process that serves only to

increase the stress levels of the veteran and it impacts negatively on them and

their family. The distress generated frequently becomes too much for the

veteran, and they give up on their claim, walk away from their family, or take

their own lives. There is no support within this process for the partners or

families of veterans with PTSD or mental illness.[39]

Criticisms of DVA's delivery models

and claims processes

5.32

In 2013, the Australian Public Service Commission conducted a capability

review of DVA. The review found that 'DVA staff are committed to supporting the

Australian veteran community' but that 'a major transformational leap forward

is required'.[40]

The capability review expressed serious concerns regarding DVA's delivery

models and compensation claims processing:

DVA’s current operating structure is a complex matrix—an

unsustainable hybrid of fragmented national and dispersed business lines,

comprising multiple service models, much of which is delivered and processed

in-house (with the exception of health services which is outsourced).

This complexity has partially been shaped by the combination

of multi-act eligibility and an increase in claims made under the MRCA which is

more challenging to administer, but primarily through the division of

responsibility for staff, policy and service delivery, all of which can be

split across two or three divisions and two or more locations. This complex

structure lacks scale and has contributed to the development of fiefdoms in

state locations and functional silos to the detriment of consistency and

efficiency of performance across key business outcomes, particularly

compensation claims processing.[41]

5.33

Mr Brian Briggs, Practice Group Leader, Military Compensation, at Slater

& Gordon Lawyers described the DVA claims processes as 'chaotic'

identifying 'fundamental problems' with its culture, leadership and equipment:

My first suggestion is this simple proposition: tackle the

chaotic claims handling by DVA. An Australian Public Service Commission review

found that the Department of Veterans’ Affairs has fundamental problems with

its culture, leadership and equipment. The department has itself admitted that

it cannot deal with the complicated needs of many physically and mentally

injured veterans. The APSC review further found that the decision-making

process at Veterans’ Affairs was a confusing mess of committees with duplicated

membership and overlapping agendas. For example, 200 individual ICT systems

operating within a single department cannot be efficient or productive. The

structure of small cells of public servants working in isolation and not

considering the whole picture has failed. Files are shipped all over the

country—one section may deal with liability before another considers incapacity

and then another rehabilitation or treatment. Permanent impairment and

compensation will be looked at by an entirely separate team. This entire

bureaucratic file shuffling and passing on of an injured member's claim causes

significant delays. The frustration of my clients at this inefficiency and

ineptitude often overwhelms.[42]

5.34

DVA emphasised its desire to improve its engagement with clients,

advising the committee that in late 2014, it commissioned and independent

survey to help improve client services which collected approximately 3,000

responses. The results showed that 89 per cent of clients were satisfied with

DVA's client service and 90 per cent of clients 'believed that the Department

is honest and ethical in its dealings and is committed to providing high

quality client service'.[43]

5.35

Mr Shane Carmody, the Chief Operating Officer of DVA, acknowledged both

the findings of the Capability Review and the comments made by Mr Briggs,

assuring the committee that DVA has strategies in place to address DVA's

operating structure; governance arrangements; information and communications

technology; approach to clients; culture and staffing; and its efforts to

formulate effective strategy, establish priorities, and use feedback:

The review team identified three key areas of focus, and we

have discussed those I think more than once during the estimates process. They

saw that we needed urgent attention to transforming our operating structure;

our governance arrangements and information and communications technology; our

approach to clients, culture and staffing; and our efforts to formulate

effective strategy, establish priorities and use feedback. All of these issues

have been identified, and strategies are in place to deal with them through

DVA's strategic plan towards 2020.

In terms of operating structure, as we mentioned during a

number of hearings, part of the creation of my position as chief operating

officer was to streamline the governance process and take control of a number

of key aspects of business. We have programs underway in terms of our clients,

culture and staffing, including a strong program such as 'It's why we're here',

a very clear program to ensure that our staff have a very good understanding of

the client base we are dealing with and the injuries and illnesses they face.[44]

Complex application processes

5.36

A number of submissions highlighted the complex and confusing

applications processes required to lodge a claim.[45]

The RSL acknowledged that DVA's 'strict processes are required to efficiently

and fairly investigate large number of claims' and that DVA has 'a defined

budget' within which it must operate but noted that this has led to an

adversarial system where DVA's focus appears to have shifted from supporting

veterans to 'looking for reasons not to provide compensation':

...many veterans feel that they are viewed by DVA as trying to

cheat the system until proven otherwise. The majority of veterans and advocates

(with whom the RSL and other advocates have contact) relate that a steadily

increasing proportion of claims seem to be proceeding to the Veterans Review

Board and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, which indicates that the DVA is

looking for reasons not to provide compensation rather than ways to support

their clients.[46]

5.37

Mr William Kearney, from the Wide Bay Burnett District of the RSL, told

the committee that most veterans, and even many volunteer advocates, do not

understand the complex legalities of the claims process and highlighted the

significant consequences for veterans and dependants if they, or the volunteer

advocates assisting them, are unable to correctly navigate the system:

The danger here is that well meant but incorrect advice, once

put on a form, signed by the applicant, then submitted to the Department is

evidence that cannot be undone. Further clarification may have a

slim chance of repairing damage but this is extremely rare. The outcome of this

is that a Veteran, at best, is locked into a lengthy appeals process, or

alternately denied benefits for life that they could have been receiving if the

case was done correctly.[47]

5.38

DVA advised the committee that it has 'invested significantly' in its

online capacity and improving clients' experiences with the claims processes.

Clients can access online claiming for a range of DVA claims and applications,

including claims for 'liability compensation following the death of a veteran, determining

qualifying service, and service pension and income support supplement'.

Furthermore, DVA advised that it has introduced an online 'single claim

process' which negates the need for clients to make separate claims under

different pieces of legislation:

The online claiming process is a single claim process rather

than the client needing to make separate claims under different pieces of

legislation. Claims will be considered under all relevant legislation to ensure

clients have access to the full range of benefits for which they are eligible.

The feedback received from ex-service representatives and departmental staff

following a trial clearly showed that a single claim form is far less complex

for clients.[48]

5.39

The DVA website now also offers a range of services including

'Entitlement Self-Assessment', which comprises a series of questions to help

existing and prospective DVA clients to assess their potential entitlements.

This may be completed by a member or former member of the ADF, (including

reservists and cadets) or dependants (partner/spouse or children). Clients can

also access 'my Account', which allows clients to access a range of DVA

services online. Clients can update contact details, access information about

accepted medical conditions, make transport bookings, claim travel expenses,

and access forms and fact sheets.[49]

Recordkeeping, communications

technology, and procedural errors

5.40

The committee received evidence regarding lost documents, long delays

whilst waiting for documents to be physically transferred between offices, and procedural

errors.[50]

Soldier On told the committee that veterans have told them of documents being

lost by DVA:

When we have spoken to a number of veterans it seems that

sometimes their records are either lost or they are not handed over correctly.

When you have a mental health injury, actually talking through the same thing

again and again can be quite confronting, especially when you have to relive

your wound. So, for whatever reason it seems that records are not passed on

correctly. That may mean they are kept correctly but not passed on correctly.[51]

5.41

One submitter told the committee that confidential medical documents

were lost by DVA on multiple occasions and outlined a number of procedural and

clerical errors that were made by DVA over the two years it took for their husband's

claim to be finalised:

Documents including confidential medical documents were lost

on more than one occasion, and requests for responses to emails, phone calls

and letters were consistently ignored. Months would pass without any updates to

the claim, despite repeated requests for information.

A number of procedural mistakes and errors of judgement

occurred during the course of the claim including:

-

the date of onset of the illness being determined incorrectly (there was

a 7 year difference)

-

not receiving the White Card for treatment costs until after liability

was established

-

not being assessed for rehabilitation services despite requests for

these services

-

the level of permanent impairment points determined by DVA was

overturned on appeal by the Veterans Review Board (VRB)

-

the procedures for determining the payment period for Incapacity

Payments were found to be incorrect and also overturned on appeal by the VRB.[52]

ICT systems

5.42

The capability review identified the state of DVA's ICT systems as a

significant issue to be addressed, describing the systems as 'antiquated':

...the department is delivering through some 200 ICT systems

which are so antiquated that new staff feel they have been transported back ‘10

years or more’. Applications are not integrated, making it difficult to obtain

a whole-of-client perspective. This is further affected by a lack of a single

client identification either within DVA or flowing from Defence through to DVA.

Past investment has been a patchwork in the absence of a definitive ICT

blueprint, which has generated cynicism and frustration.[53]

5.43

Mr Carmody agreed that DVA has 'antiquated' ICT systems, assuring the

committee that DVA was working to modernise and digitise its systems 'within

the funding' available:

We do have challenges—I will admit those—without a doubt. I

mentioned some during a hearing last week. We have antiquated ICT systems. We

are doing our best to modernise those systems within the funding that we have

available. We are doing our best to digitise our systems to move files off

paper and on to digital systems. It will take time.[54]

Case coordination

5.44

A number of submissions highlighted the lack of continuity when dealing

with DVA and called for veterans making claims regarding mental ill-health to

be assigned a case officer or staff member to act as a single point of contact.[55]

One submitter called for DVA to assign a case officer to act as a single point

of contact for claims relating to mental ill-health:

Each time we contacted DVA we would speak with a different

staff member, who inevitably passed us on to someone else, usually in another

state. A dedicated case manager, with specialist training in mental health

awareness should be allocated to each case that involves mental illness.[56]

5.45

DVA advised the committee that a small proportion of DVA clients are categorised

as 'vulnerable with complex needs'. This might be because the client has

serious wounds, illnesses, or injuries as a result of their service; a severe

mental health condition; relationship or interpersonal difficulties; complex

psychosocial needs; or a mix or some of all of these factors. DVA noted that,

in general, case management refers to support provided to clients for:

-

access to DVA systems and supports, usually referred to as 'case

coordination', which are provided through DVA's case coordination service; and

-

access to health care and community service, usually referred to

as 'clinical care coordination', which are provided through DVA's health care

card arrangements (for instance, through social workers) and also through the

Veterans and Veterans Families Counselling Service (VVCS).[57]

5.46

DVA informed the committee that in the 2015-16 budget, the government

funded 'a new measure', worth approximately $10 million over the forward

estimates, to improve DVA's case coordination:

The measure will improve DVA's capacity to provide one-on-one

tailored packages of support to veterans with complex needs, including mental

health conditions. It will also improve the level of support and early

intervention assistance provided to an increasing number of veterans with

complex needs, particularly those returning from recent conflicts.[58]

5.47

Furthermore, as of 8 February 2016, DVA has implemented a single,

nationally consistent, model for supporting complex and multiple needs clients.

DVA advised that the new model focuses on supporting clients with mental health

conditions and/or complex needs and aims to provide a single point of contact:

In line with the aim of the Budget initiative, there is a

focus on supporting clients with mental health conditions and/or complex

needs. Staff working within the new model will provide a single point of

contact where appropriate, help clients navigate DVA’s processes to ensure they

are accessing all of their entitlements, and connect clients with other

community-based services and support where relevant.[59]

5.48

DVA also provided data regarding client update of the various case

management support options (see table 5.1).

Table 5.1–Client update of case

management support

|

Program/Support

|

Data on client uptake or population*

|

|

DVA’s case coordination service

This is a single service providing those clients requiring

additional support with a primary or single point of contact for the whole of

the Department.

|

From January 2010 to June 2015, over 1,100 clients were

referred to the Case Coordination Program.

As part of the information exchange strategy between Defence

and DVA, in 2014-2015 Defence issued DVA with:

17 NOTICAS* priority notifications; and

961 medical separation notifications.

*Where a member is medically classified as seriously or very

seriously wounded, injured, or ill (defined as an injury or illness that

endangers the person’s life; significantly disables the person; or materially

affects the person’s future life).

|

|

Social work services under DVA’s allied health

arrangements

Social workers help clients overcome a range of problems in

relation to stressful life events such as death or divorce and assist them to

deal with family, health, employment, income support or accommodation related

issues. The services provided by eligible social workers may include:

-

general counselling and case management; and

-

health service co-ordination and facilitating access to

community services.

|

In 2014-15, there were 906 clients who received support under

DVA’s social work allied health items, for treatment or case coordination.

|

|

Veterans and Veterans Families Counselling Service (VVCS)

VVCS provides free and confidential, nation-wide counselling

and support for war and service-related mental health conditions, such as

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance

and anger.

VVCS supports a number of clients in complex situations with

comorbidities and or who find it difficult to engage and manage the range of

health and social care services they require.

|

In 2014-15, there were 227 clients who had their cases

managed by VVCS. This compares with 126 complex care cases managed

in 2013-14.

|

* Note: the same client may

access more than one type of support.

Department of Veterans'

Affairs, Supplementary Submission 35.1, pp 2–3.

Timeframes

5.49

A number of submissions raised concerns regarding the time taken to

process claims.[60]

Slater & Gordon Lawyers and KCI Lawyers called for the introduction of time

limits for the processing of claims. Slater & Gordon Lawyers noted that

state and territory bodies as well as international bodies have statutory

timeframes in which decisions are made regarding the processing of claims for

assistance and compensation:

...most important, is that time frames are now put in place to

ensure that claims for help and other things are dealt with. Every state and

territory system in Australia has time frames for decision making. Defence

personnel in the UK and US are protected by time frames for decision making.

But in Australia there are none, so injured personnel can literally be left

waiting for years...An increase of $10 million announced in the latest budget to

increase the numbers of delegates who make decisions is welcome but will not

adequately solve the problem unless time frames are mandated. I strongly urge the

committee to consider the issue of deeming time periods, which will have a

significant benefit in assisting not only the PDSD sufferers but also all of

our injured military personnel.[61]

5.50

KCI Lawyers commented that the long processing times unfairly deny veterans

and their families access to much needed assistance:

DVA continue to cause Veterans and their families substantial

delays as they have no time limits imposed to make timely decisions. This

remains a vexed issue when compared to other Workers' compensation...The time has

well and truly come for DVA to make a decision within a reasonable and a

defined period. The old adage of "justice delayed is justice denied"

is also true when considering the delay to provide compensation payments by

making timely and accurate decisions is akin to denying the benefit.[62]

5.51

DVA assured the committee that 'the Government is very focussed on

improvements to reduce the time taken to process compensation claims'

describing it as a 'key early intervention initiative'.[63]

The average times taken to process compensation claims under the VEA and

liability claims under MRCA and SRCA for the financial years 2011-12 to 2013-14

are listed in table 5.2.

Table 5.2 – Time taken to process

claims

|

|

TARGET AVERAGE

days

|

2011-12 OUTCOME

days

|

2012-13 OUTCOME

days

|

2013-14 OUTCOME

days

|

2013-14 CHANGE

days

|

|

VEA

|

75

|

74

|

79

|

75

|

-4

|

|

MRCA

|

120

|

158

|

155

|

144

|

-11

|

|

SRCA

|

120

|

180

|

171

|

160

|

-11

|

Department of Veterans'

Affairs, Submission 35, p. 28.

5.52

DVA disagreed with calls to introduce statutory timeframes. Ms Lisa

Foreman, First Assistant Secretary, Rehabilitation and Support, advised the

committee that statutory timeframes have been considered in the past and were

found to be unsuitable for DVA's unique situation:

Last year, we tabled a report in the Senate on the review of

statutory time frames which looked at the options that we might be able to

adopt in relation to our claims processes, but overall there are two

significant issues in relation to compensation claims that we receive compared

to compensation claims under states' compensation and private compensation

schemes. Firstly, we have no time limit on when a member—a veteran—can lodge a

claim. So an injury could have occurred in the forties, the fifties or the

sixties, and a veteran is still able to lodge a claim with us; there is no

limit. We do not have any directions on the state of the

claim that we receive. Essentially, a veteran can put a claim in which just has

their name, address and injury, and they sign it. A lot of other compensation

schemes actually will not accept a claim until it is fully completed. In our

case, that would mean that it has not only the details of the veteran but also

reports from their medical specialists or doctors about the nature of the

injury and the illness, proof of identity that the veteran has served, and

details of where they served and when they served. We do not do that; we allow

veterans to come in and immediately give us their claims. We then go away and

try and get that additional information. We will contact their specialists and

ask them to produce a report. We will contact Defence and ask them to produce

details of their medical records and the incident that gave rise to the

compensation. I think, overall, we are in a very different position to other

compensation schemes in Australia.[64]

5.53

Mr Carmody also expressed concerns regarding the introduction of

statutory timeframes, noting that it could damage the integrity of the claims

system:

...one of the key points in statutory time frames is what you

wish to achieve. For example, do you want to have a deemed acceptance at the

end of a particular period? If that were the case, that would encourage

everybody to go slow on their claims process, because we have to collect all of

the information. If you were to have a deemed acceptance, people would be

reluctant to put in their material, because at the end of a particular period

of time we are going to accept it anyway. That would be unfair across the whole

system. If you decided to have a deemed rejection at the end of a particular

period, if somebody gets 95 per cent through their claims process and the time

elapses, they have to go back and start again. So there are some real issues in

trying to manage this. A great amount of our time that is taken to process is

taken up with collecting information which in other jurisdictions would be

provided in advance. That is probably the simplest answer.[65]

Availability of services in regional and remote areas

5.54

Some submissions highlighted a lack of available services, especially in

regional or remote areas, as a significant barrier to treatment.[66]

Ms Maria Brett, Chief Executive Officer of Psychotherapy and Counselling

Federation of Australia, told the committee that due to workforce shortages,

veterans seeking treatment may have to wait a 'significant amount of time':

...particularly relates to rural and regional areas, because we

know there are workforce shortages. If you are trying to access one of the

outreach counsellors from VVCS and you live in a place where someone is not

available, you will actually be waiting, and that sometimes can be for quite a

significant amount of time to get a service. This is why, in our discussions

with the health minister we are very interested in potentially using

counsellors to participate in a rural and regional trial, and that could be

something potentially that DVA—[67]

5.55

Ms Catherine O'Toole, Chief Executive Officer at Supported Options in

Lifestyle & Access Services (SOLAS), advised the committee that 'specialist

mental health services are very light on the ground in regional areas'. Ms

O'Toole advised that SOLAS was working to build capacity in northern and

western Queensland:

Specialist mental health services are very light on the

ground in regional areas. Our organisation made a commitment, when we got

federal funding some time ago, that we would work to build the capacity in our

regional areas. That is why we subcontract in Charters Towers, Ingham, Ayr,

Burdekin, Richmond and Hughenden—because there were no specialist mental health

services. We have been able to build that capacity in that community. It is

much more financially viable as well. We have also created jobs and built skill

bases in those communities.[68]

5.56

DVA acknowledged that, as it operates and purchases services from within

the broader mental health system, workforce shortages can impact on the

availability of services for veterans in regional and remote areas:

DVA operates within a broader mental health system and it is

important to recognise that while there has been significant expansion of

mental health services over the past two decades in Australia, this sector

continues to have workforce shortages in the face of growing demand especially

in some regional areas.[69]

Committee view

Stigma and perceived barriers to

care

5.57

Early identification and treatment of mental ill-health is essential for

achieving the best outcomes for ADF members and veterans with mental

ill-health. As such, the committee is very concerned that perceived stigma

surrounding mental ill-health continues to be identified as a significant

barrier to ADF members and veterans seeking treatment for mental ill-health.

5.58

Evidence of ADF members who were brave enough to report mental

ill-health and seek treatment being ostracised, ridiculed, and accused of

'malingering' is deeply disturbing and completely unacceptable. The committee

acknowledges that Defence has introduced a range of educational resources and

activities to reduce stigma surrounding mental health; however, it is clear

that more must be done to root out and denounce stigma regarding mental

ill-health.

Impact of mental health on career

prospects

5.59

The MHWP study found that the highest rated barrier to ADF personnel

seeking help was the concern that seeking help would reduce their deployability

(36.9 per cent). The committee acknowledges that is a legitimate fear and a

difficult one for Defence to address. Defence has an obligation to ensure that

ADF member's duties do not detrimentally affect their health, that ADF members

can undertake their duties without compromising the safety of themselves or

others, and that the ADF as a whole maintains it operational capability.

5.60

The committee understands the principle that it would be inappropriate and

irresponsible for Defence to deploy ADF members who are not mentally well

enough for deployment, in the same way as it would be inappropriate for an ADF

member who is not physically well enough to be deployed. However, this does not

absolve Defence of its responsibility to address these fears. Defence should

continue to emphasise the benefit of early identification and treatment of

mental ill-health for an ADF members' long-term career prospects when

considering seeking assistance for mental ill-health. Defence should also encourage

ADF members to plan beyond their next deployment by showing examples of members

who have successfully deployed after rehabilitation for mental ill-health.

5.61

An ADF member who chooses not to disclose or treat mental ill-health,

and is subsequently deployed, is exposing themselves to significant risk of

further deterioration of their mental health. This may result in a much more

serious mental health condition which may ultimately lead to the ADF member

being medically downgraded, medically discharged, or even the inability to work

at all. Comparatively, an ADF member who disclosed and sought treatment for

mental ill-health early may have their deployment delayed, but is significantly

more likely to have positive mental health outcomes. This may result in later

deployments, after mental health concerns have been addressed, and ultimately

result in a longer and more successful career in the ADF.

Recommendation 11

5.62

The committee recommends that Defence mental health awareness programs do

more to emphasise the benefit of early identification and treatment of mental

ill-health for an ADF members' long-term career and encourage ADF members to plan

beyond their next deployment.

Recommendation 12

5.63

The committee recommends that the Department of Defence and the

Department of Veterans' Affairs develop a program to engage current and former

ADF members, who have successfully deployed after rehabilitation for mental

ill-health, to be 'mental health champions' to assist in the

de-stigmatisation of mental ill-health.

DVA delivery models, claims

processes, and ICT systems

5.64

Veterans and their families who are seeking assistance and treatment for

mental ill-health must engage with DVA to receive it. Therefore, the extent to

which DVA processes act as a barrier to the early identification and treatment

of mental ill-health is directly proportionate to the ease and speed with which

veterans' claims are processed. As such, the committee is deeply concerned by

evidence that the DVA claims process can be detrimental to the mental health of

veterans seeking assistance and treatment for mental ill-health.

5.65

The Australian Public Service Commission's capability review highlighted

considerable failings regarding DVA's operating structure; governance

arrangements; information and communications technology; approach to clients;

culture and staffing; and its ability to formulate effective strategy,

establish priorities and use feedback. The committee acknowledges that DVA has

strategies in place to address these shortcomings; however, it is clear that more

must be done to ensure that veterans are able to quickly access the assistance

and treatment they require.

5.66

The committee commends DVA for its efforts to simplify its complex claims

process. The introduction of an online 'single claims process', which negates

the need for clients to make separate claims under different pieces of

legislation and ensuring that clients have access to the full range of benefits

that they are eligible for, is a significant step towards improving client

engagement. The committee also notes DVA's introduction of online 'entitlement

self-assessment' and 'my Account' services.

5.67

The committee is very concerned by the evidence it received regarding

lost documents, long delays whilst waiting for documents to be physically

transferred between offices across different states and territories, and

procedural errors. DVA's 'antiquated' ICT systems appear to be at the root of

many of these concerns. The committee is not satisfied by DVA's comments that

'it will take time' to modernise these systems within the funding that it has

available. The digitisation of records and modernisation of ICT systems must be

made a priority and should be funded accordingly.

Recommendation 13

5.68

The committee recommends that the Department of Veterans' Affairs be

adequately funded to achieve a full digitisation of its records and modernisation

of its ICT systems by 2020, including the introduction of a single coherent

system to process and manage claims.

5.69

Good case coordination is essential to ensuring that veterans and their

families who are seeking assistance for mental ill-health can navigate the

claims process with the minimum impact on their mental health. The committee is

satisfied that DVA recognises this and is encouraged by the government's recent

investment to improve DVA's case coordination. The committee is also pleased to

note DVA's recent implementation of a single, nationally consistent, model for

supporting complex and multiple needs clients, which will aim to provide a

single point of contact during the claims process.

5.70

Early identification and treatment of mental ill-health is essential for

achieving the best outcomes for ADF members and veterans with mental

ill-health. As such, it is essential that claims are processed in a timely

fashion, to ensure that veterans and their families are able to receive

assistance and treatment as soon as possible. The committee commends DVA for

its non-liability mental healthcare provision and its recent expansions to the

eligibility requirements to receive it.

5.71

The committee acknowledges DVA's assurances that it is aware of the

importance of improving the timeliness of claims processing. The committee is

satisfied that the strategies DVA is implementing to improve the timeliness of

its claims processing, together with the digitisation of records and

modernisation of ICT systems, will ensure that claims are processed within

acceptable timeframes.

5.72

The committee acknowledges calls to introduce statutory timeframes;

however, based on the evidence received, the committee is not convinced that

mandating a timeframe will benefit veterans and may have unintended

consequences.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page