Factors driving workplace gender segregation in Australia

Introduction

3.1

As explained in Chapter 2, vertical and horizontal gender segregation

manifests itself across much of the Australian workforce. Workplace composition

is much more than just a function of individual choices and actions. Patterns occur

across industries and occupations because individuals’ choices are constrained by

a range of structural factors and social norms.

3.2

In Australia, systemic factors such as caring responsibilities and the

availability of flexible work have combined with expectations about traditional

gender roles to restrict the range of roles that are available (or perceived to

be available) to men and women.

3.3

As will be discussed in Chapter 4, the gender segregation that results

from this narrowing of choices has ongoing consequences for individuals and our

economy. Unfortunately, without deliberate action, neither the consequences of

gender segregation nor its causes are likely to ease in the future.

3.4

Globalisation and technological change are driving wholesale changes to both

the structure of Australia’s economy, and the jobs that are available to

Australians. The ongoing influence of structural and social factors, however,

means that new opportunities continue to reflect gendered patterns of work.

3.5

It is predicted that professional, scientific and technical services,

education and training, retail trade, health care, and social assistance will

provide for more than half of all new jobs over the next five years.[1]

Although women have relatively large shares of employment in four of these five

industries, they are under-represented in senior roles. Further, these feminised

jobs and industries have lower average remuneration[2]

than those dominated by men.

3.6

This chapter sets out (1) the structural and systemic factors and (2)

the social norms and expectations that have led to gender segregation in the

past, and that continue to impose themselves on Australia’s workforce.

3.7

In doing so, it is necessary to traverse many issues regarding women’s

work and economic activities, such as the gendered responsibility for care, part-time

work and flexibility, child care, women on boards and in senior management

positions, and gender stereotypes about work. These issues that have already

been covered in far greater detail by other, more specialised parliamentary

inquiries than it is possible to do in this report.

3.8

This report aims to provide only a high level understanding of these

issues, and instead concentrates on the contribution they make to gender

segregation in the workplace.

Structural and systemic factors

Consequences of the gendered

responsibility for care

3.9

Responsibility for unpaid care is not evenly distributed. Women shoulder

the majority of the duty of caring for the young, the sick and the elderly in

their families, friendship groups and communities.

3.10

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) estimated in 2013 that 5.5

million Australians between 15 and 64 years had unpaid caring responsibilities,

and 72.5 per cent of these were women.[3]

3.11

It is beyond the scope of this inquiry to definitely address questions about

whether this division of caring responsibilities is either fair or efficient,

but the committee notes that it places a heavy emotional, time and financial

burden on women.

3.12

The failure of our workplaces and workplace relations system to

adequately respond to the gendered nature of care, however, creates structural

and systemic pressures leading to gender segregation.

3.13

This section examines these structural and systemic factors including

the availability of part-time and flexible working arrangements, child care,

and opportunities for advancement, as well as proposed responses to these

factors.

Part-time and flexible work

The need for work that can fit

around care

3.14

The gendered nature of caring responsibilities forces women to seek

flexible and part-time employment.

3.15

Ms Amanda McIntyre, First Assistant Secretary, Office for Women, Department

of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) stated that:

Once women have entered the workforce, staying

engaged—particularly after they have children, but also where they have other

responsibilities such as elder care—is influenced by these caring

responsibilities. The disparity in the share of unpaid care due to the

entrenched underlying gender stereotypes impacts women's participation.[4]

3.16

Women comprise 46.2 per cent of all employees in Australia but they are

heavily concentrated in the part-time workforce, constituting 71.6 per cent of

all part-time employees. Women make up 36.7 per cent of all full-time employees

and 54.7 per cent of all casual employees.[5]

3.17

Australia has one of the highest rates of part-time work in the world.

Amongst Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

countries, for example, Australia has the third-lowest rate of women in

full-time employment.[6]

3.18

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2015 ̶ 16 more than two in

five employed women worked part-time (44 per cent), compared with 15 per cent

of employed men.[7]

3.19

According to a 2012 report by the Grattan Institute:

While 55 per cent of employed women work full time, 85 per

cent of employed men do, with the remainder working part time. These rates are

substantially lower than in many other OECD countries...While Australia is just above

the OECD average, the average includes countries with very low participation

rates, such as Greece.[8]

3.20

Some of these are northern European countries with a distinct social

compact which may not be easily replicated in Australia. However, female

workforce participation is also substantially higher in Canada, a country that

is culturally, economically and institutionally similar to Australia.

3.21

The Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) reported that flexible work

is a priority for women:

Over successive rounds of enterprise bargaining, when we go

in to bargain for a workforce that is predominantly women who may well have

caring responsibilities, their No. 1 priority is making sure that their rosters

cannot change without advance notice, that they get parental leave, that they

have caring leave when they need it to care for children et cetera. ... people

could say, 'Well, people get what they want,' but it is a bit of a perverse

consequence that, because women have historically taken on more caring

responsibilities, they have had to [prioritise] their bargains in a certain

way.[9]

The availability of flexible and part-time

work

3.22

Not all industries and workplaces are equally flexible, however. The

uneven distribution of flexible and part-time employment opportunities funnels

women into particular industries and sectors.

3.23

According to Workplace Gender Equality Unit (WGEA) data for 2015 ̶ 16 (see Figure 3.1

below):

-

female-dominated organisations have the highest proportion of

part-time and casual employment as a proportion of all employees;

-

female-dominated organisations have the lowest proportion of

full-time employees as a proportion of all employees compared to male-dominated

and mixed industries; and

-

the proportion of part-time employees in male-dominated

organisations in 2015 ̶

16 is only 5 per cent.[10]

Figure 3.1—Proportion

and number of full-time, part-time and casual employees, WGEA data 2015 ̶ 16

3.24

WGEA reported that less flexibility in male dominated workplaces tends

to deter women:

Higher-paying male dominated workplaces have smaller

proportions of part-time employees—around the five per cent mark. They tend to

offer less flexibility and their full-time employees tend to work longer hours.

These are all factors that may deter women with families and caring

responsibilities from entering male dominated industries and occupations, so

they often have to gravitate to the lower-paying female dominated industries

because they offer the highest proportion of flexible work—particularly

part-time and casual work.[12]

3.25

In industries other than health and social services, obtaining flexible

workplace arrangements can be difficult. Australia 'lacks an effective

enforcement or appeal mechanism providing little protection or support to the

most vulnerable in the workforce such as precarious, unskilled, low paid or

un-unionised workers' when requesting flexible workplace arrangements.[13]

3.26

The Fair Work Act 2009 provides employees with at least 12

months’ continuous service (and long-term casuals) with the right to request

flexible working arrangements in a range of circumstances, including where the

employee is the parent, or responsible for the care, of a child who is of

school age or under. There is also a specific right for parents returning from

parental leave to request part-time work.[14]

3.27

Department of Employment (DoE) noted that, while all modern awards and

enterprise agreements provide for individual flexibility arrangements (IFAs), there

has only been a small take-up of these arrangements (two per cent per cent of

employees).

3.28

DoE spoke about the effectiveness of the right to request flexible work

provisions:

...the Fair Work Commission...found that there was 80 per cent

in 2009 ̶ 2012,

or thereabouts, and 90 per cent where requests were granted without any change.

They are really very high percentages that have been indicated through those assessment

mechanisms that people are having their requests granted.[15]

Flexibility for whom?

3.29

The Australian Industry Group (Ai Group) mentioned barriers to flexible

workplace practices for men and women within the workplace relations framework,

noted by the Productivity Commission (PC) in the Final Report of its recent

review of the Australian workplace relations framework. Ai Group indicated that

this view is shared by many employers:

These inflexibilities make it very difficult for employers to

implement alternative working arrangements for workers who desire (or require)

more flexible working arrangements.[16]

3.30

The Victorian Trades Hall Council (VTHC) cautioned that flexibility

means different things to employers and employees. According to Professor Heap,

Lead Organiser, VTHC:

...when the employers are talking about it, they are generally

talking about flexibility for business arrangements, and that is why they

promote insecure work arrangements, because it gives them the ultimate choice

to be able to move their labour market around.

But, when women are talking about flexibility, they are

talking about being able to have roles which will allow them to do drop-offs

and pick-ups in relation to care and school and ensure that they can work their

hours of work around the obligations of their family.[17]

3.31

Carers Australia NSW noted that some workplaces have begun to implement

a 'flexibility by design' approach, whereby flexibility is a priority in

determining the structure of individual positions and whole teams:

Proponents of this measure suggest that it prevents the need

to accommodate individual scenarios and instead recognises that all employees

are likely to have some form of caring commitment outside of work at some

stage.[18]

Addressing the need for flexible

and part-time work

Legislative changes

3.32

A number of submissions recommended specific legislative changes to

strengthen employee access to flexible work arrangements, as follows:

3.33

The Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (AMWU) recommended the

following changes to the Fair Work Act:

-

amend Part 2-2 (section 84 of the National Employment Standards)

to include a right for a full-time employee to return to work from parental

leave on a part-time basis, or the right for a part-time employee to return on

reduced hours, with a right to return to pre-parental leave hours until the

child is school age; and

-

amend the right to request flexible work provisions to allow a

role for the Fair Work Commission where there is a disagreement between the

employer and the employee regarding requests for flexible work.[19]

3.34

Representatives from the AMWU told the committee that:

If you are making an application due to caring arrangements

for some alterations of changes of hours, the employer can easily dismiss the

application without sitting down, really, and discussing how it can be managed

or accommodated.[20]

3.35

New South Wales Council of Social Service (NCOSS) suggested that

flexible working arrangements should cover all forms of caring responsibilities

and be available to men and women:

...flexible working arrangements need to cover all forms of

caring responsibilities and be actively available to men and women...it is a

cultural shift.

The Paid Parental Leave Scheme, we would say, could be

improved over time to allow for 26 weeks paid parental leave, ideally, offering

four weeks to a partner on a use-it-or-lose-it basis. ...we need strong and

responsive authorities to advocate for these positions and strong, independent

monitoring and evaluation mechanisms that can hold us to account. The ASU recommended

amending the Sex Discrimination Act to recognise indirect discrimination on the

grounds of 'family responsibilities', and include a positive duty on employers

to reasonably accommodate the needs of workers who are pregnant and/or have

family responsibilities.[21]

3.36

Some witnesses were cautious about introducing further regulation,

asserting that increasing the regulatory burden could damage the performance

and competitiveness of Australian business.[22]

3.37

Ai Group recommended promoting dialogue between employers and employees

rather than increasing regulation.[23]

Normalising flexible work

arrangements

3.38

Some submitters emphasised the benefits of normalising flexible work

arrangements. Despite the negative stereotype, there are potential benefits for

employers; a study by Ernst & Young found women working part-time waste the

least amount of time at work.[24]

3.39

Several submissions recommended measures to better manage the care

responsibilities of both men and women. The AHRC's 2013 Investing in Care report

included measures like:

-

normalising flexible work arrangements for both men and women to

ensure the equal distribution of unpaid care work; and

-

preserving and improving paid parental leave measures, including

the introduction of ‘use it or lose it’ father-specific parental leave modelled

on the schemes that exist in Nordic countries.[25]

3.40

United Voice proposed a model of care work in which the care of young

children and the elderly is shared between state-funded providers and both

parents, underpinned by significantly higher wages for care work in undervalued

industries, and expanded legislative mechanisms for parental leave and flexible

working provisions.[26]

Access to child care

3.41

Access to child care is important in helping women manage caring

responsibilities. Affordable and reliable child care provides women with more

options, and allows them to take on less flexible or full-time work in fields

that otherwise would not be open to them.

3.42

The VTHC cited research establishing a positive correlation between

increasing child care uptake and lowering of the gender earnings gap, and the

level of child care subsidies and labour force participation.[27]

3.43

Access to child care accordingly is capable of mitigating some of the

structural factors contributing to workplace gender segregation. Submitters

indicated, however, that there were issues in finding affordable and reliable child

care.

3.44

Department of Employment and Training (DET) pointed out that the Productivity

Commission has estimated that:

...there may be up to 165,000 parents (on a full-time

equivalent basis) who would like to work, or work more hours, but are not able

to do so because they are experiencing difficulties with the cost of, or access

to, suitable child care. These are parents (mostly mothers) who are currently either

not in the labour force or are working part time.[28]

3.45

DET indicated that returning to work after having children has a

significant impact on job choices, with implications for gender segregation as

well as their life-long earning potential':

Where accessible and affordable child care is not available,

parents may be unable to return to their job of choice but instead may be

forced into jobs that provide flexibility for part time work.[29]

These include investment in the care economy and ensuring the

payment of decent wages and conditions in the early childhood education and

care sector.[30]

The need to invest in child care

3.46

Several submissions noted the need to invest in the early childhood

education and care sector. On the one hand, access to child care is a factor

leading to gender segregation. On the other hand, as a low paid, female-dominated

industry offering flexible work, the child care sector is also a case study of

the consequences of gender segregation.

3.47

Professor Meg Smith, a member of Work + Family Policy Roundtable (W+FPR),

recommended policy measures that directly address the undervaluation of work commonly

undertaken by women in sectors such as child care.

3.48

The ACTU recommended a range of specific policy measures aimed as

supporting workers with caring responsibilities.

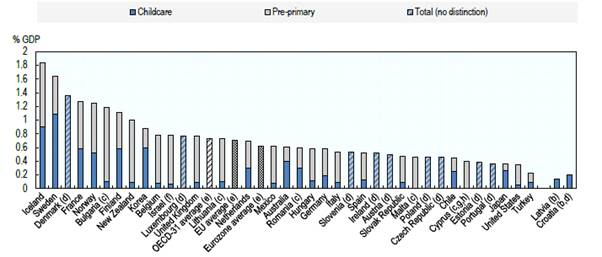

Figure 3.2—Public spending on early

childhood education and care as a % of GDP, 2013 and latest data available

Note:

OECD Social Expenditure Database (OECD countries); Eurostat (for Bulgaria,

Cyprus, Croatia, Lithuania, Malta and Romania).

Source: PF3.1: Public

spending on child care and early education, OECD Family database, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_1_Public_spending_on_child

care_and_early_education.pdf (accessed 10 May 2017).

3.49

The committee noted the findings of recent research into the benefits

for investing in the care economy in comparable jurisdictions (see Figure 3.2

above). A 2016 analysis of seven OECD countries by the UK Women's Budget Group

concluded that investing the equivalent of two per cent of GDP in the female-dominated

care industry would produce larger employment effects than the equivalent investment

in the male-dominated construction industry.[31]

3.50

Chapter 5 provides further detail about polices and legislation that

address gender segregation in comparable overseas jurisdictions.

The career cost of flexible and part-time

work

3.51

Women’s need for flexibility in work arrangements has contributed to

vertical and horizontal gender segregation in Australian workplaces, with an

over-representation of women professionals in lower-paid roles and the

under-representation of women in senior, management and leadership roles.[32]

3.52

Women regularly choose part-time or casual employment 'below their skill

level' so that they can manage both paid work and unpaid family

responsibilities, suggesting that the availability of part-time work is a

significant factor contributing to vertical and horizontal gender segregation

in Australian workplaces.[33]

3.53

The VTHC noted, for example, that women frequently reported having to

take lower status roles in order to get part-time hours or being forced to move

to less secure working arrangements in order to achieve the flexibility they

needed to accommodate their caring responsibilities.[34]

3.54

These decisions are sometimes made for women. Traditional career evaluations

place a higher reward on a full-time uninterrupted career trajectory. A broken

career pattern can lead to stereotyping of women as less committed to their

careers. This is also associated with professional isolation, difficulties with

re-entering the workforce, and pressure to return from maternity leave early.[35]

3.55

Many women with caring responsibilities feel they are penalised in their

jobs, and are more likely to be employed in lower paying jobs and in less

secure employment.[36]

3.56

The Police Federation of Australia (PFA) provided some results from

their survey of flexible working arrangements (FWAs) in the police force.

Results indicate that 80 per cent of police on flexible working arrangements are

women. Additionally, 85 per cent of police on FWAs are constables, with

sergeants and commissioned officers under-represented. The draft report noted

feedback from respondents:

...because they are not full-timers they [believe they] are

consistently overlooked, not being considered for or offered training.[37]

Social norms and stereotypes

3.57

Social norms and gender stereotypes reinforce gender segregation by

limiting the roles deemed appropriate for men and women. This section will examine

how gender expectations express themselves in education, training and

throughout a person’s working life. It will then examine female participation

in STEM fields before considering men and women working in non-stereotypical

industries and jobs.

Gender stereotypes about work

3.58

Gendered stereotypes of industries and occupations play a crucial role

in creating gender segregation in the Australian workforce.

3.59

According to Women in Super (WiS):

There are deeply entrenched views in Australia regarding the

types of careers that girls/women have traditionally been expected to do and

what boys/men should do. Although this has changed somewhat over recent years,

the gender segregation data produced by WGEA shows that it may well be the

expectations of the workforce especially graduate and Gen Y’s that has changed

but not the workforce itself.[38]

3.60

Although gender stereotypes can sometimes lead to men and women opting

out of particular fields, in many cases these decisions are made for them by

companies’ recruiting and HR practices. Both of these situations are considered

below.

The role of gender stereotypes in

individual decisions

3.61

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) emphasised that,

along with other measures, there is a need to challenge broader societal

stereotypes in order to bring about cultural change within workplaces:

Employer efforts to achieve gender equity in the workplace

are important and are to be encouraged, but should run in parallel with a

broader social discussion that challenges stereotypes and effects cultural

change, so that women and their partners can make considered choices about the

way they balance work and personal priorities.[39]

3.62

WGEA described gendered stereotypes:

...few men are attracted to lower paying female dominated

industries because of the stereotypes around men's work, which has most likely

contributed to the lack of males in health and education.[40]

3.63

Ai Group described the difficulties in recruiting females to jobs

traditionally done by males, even when actively targeting females.[41]

3.64

The AMWU described about the reasons for the low numbers of women in

technical and trade positions:

Young women are still diverted, if you like, at the high

school level, from considering going into non-traditional fields. There is

report that was released last year that shows that, if they do so choose, there

is quite an extreme amount of harassment and bullying that the young women

face—they have to go through trials and tribulations to complete their

apprenticeship—so there need to be structural changes.[42]

The role of gender stereotypes in

employer practices

3.65

The Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (BCEC) reported that unconscious

bias contributes to the pay gap:[43]

The issue of unconscious bias was flagged as one explanation

for really quite a strong finding in the last WGEA gender equity report, which

sought to compare the pay of male and female employees on graduate training

programs in private organisations.

...until we deal with the issue with unconscious bias, it will

be very hard to drive gender pay gaps to zero. A recent survey of Australia's

business, government and not-for-profit sectors found that gender bias in

feedback and promotion decisions also inhibits the equal progress of women into

leadership positions, with 60 per cent per cent of men and 41 per cent per cent

of women promoted twice or more in the past five years.[44]

3.66

A number of submitters provided evidence about programs they were

undertaking to reduce the role of gender stereotypes and unconscious bias in

their organisations.

3.67

Ai Group reported that its members are seeking to remove unconscious

bias in recruitment and promotion.[45]

3.68

The Reserve Bank's share of female graduates, from fields as diverse as

economics, finance, law, mathematics and statistics, has increased as a result

of changing its recruitment practices:

We engaged more intensively with universities so that

students knew about the Reserve Bank as a place where one can have a rewarding

career in an inclusive environment.

We used separate teams for shortlisting and interviewing, to

reduce unconscious biases at later stages of the selection process. We moved

our recruitment campaign earlier and started fast-tracking the obviously good

candidates to interview and decision before deciding on the full slate of

interviewees.[46]

3.69

The ACCI argued that business leaders can play an important role in

driving structural and cultural change within their own organisations and

promoting the benefits of a diverse workforce more broadly.

3.70

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) reviews practices to

identify and address unconscious bias as part of the Australian Public Service

(APS) gender equality strategy. The strategy:

...requires all agencies to have tailored but ambitious gender

equality targets across all leadership levels and business areas and to

implement action plans to reach them. Every portfolio department has now done

this and many of those plans are already public. Agencies are also required to

review their recruitment, retention and performance management practices to

address areas of gender inequality, including by identifying and mitigating

unconscious bias.[47]

Workplace culture

3.71

Bias is not always unconscious and not always covert. This committee

received troubling evidence about workplace cultures that were threatening and

hostile to women.

3.72

The Victorian Trades Hall Comission undertook a survey of women’s

experiences at work:

-

64 per cent of respondents have experienced bullying, harassment

or violence in their workplace;

-

60 per cent of respondents reported feeling ‘unsafe,

uncomfortable or at risk’ in their workplace;

-

44 per cent of respondents reported experiencing discrimination

at work;

-

23 per cent of respondents don’t feel that they are treated with

respect at work; and

-

19 per cent of respondents cited ‘unsafe work environment’ as a

factor in their decision to leave paid work.[48]

Education and training

3.73

Gendered stereotypes about work arise earlier in individuals’ careers

through gendered expectations about education and training.

3.74

PM&C acknowledged that:

Participation in the workforce in particular industries ...is

influenced early by gender stereotypes, which, in turn, influence the

educational choices that women make and determine the knowledge and skills that

women and men bring to the workplace.[49]

3.75

WGEA noted that gender segregation is

reinforced by course choices and graduate career choices:

...graduates are overwhelmingly entering fields dominated by

their own gender—almost

90 per cent of the graduates in health care and social assistance industry are

women, while men continue to dominate construction (almost 80 per cent) and

mining (almost two-thirds).[50]

3.76

NCOSS described how unconscious bias affecting career counselling:

...what we hear through our young women's network is that at school

there is unconscious bias through the careers counselling process. Indeed, by

not naming it upfront I think allows for the unconscious bias to continue.[51]

3.77

NCOSS spoke further about how unconscious bias also affects the way

girls experience their first jobs:

...for a lot of young women [they] have their first job

concurrent with being at school. So they may be working at the local

supermarket or in a coffee shop. What you are seeing is you are at school and

you are not perhaps being developed and shown opportunities in the same way

around STEM. But then you also go into the workplace for your part-time job and

you are prevented...from doing any of the auditing of the financials and the

stocking out the back and you are put out the front to run the checkout. The

'checkout chick' phenomenon is a thing.

Girls do not get the job as the barista. That has a level of

skill attached to it. So the boys are the baristas and the girls are the

waitresses. All of these things we hear—and we are surprised to hear, ...I hear

these young women who are aged between 15 to their mid-20s in our group telling

us these things...That is today in Australia. But that is a reality.[52]

3.78

Given the importance of gender stereotypes in shaping career decisions,

it is unfortunate that there is limited consideration of gender, or the

specific needs of women and girls, in career guidance materials.

3.79

In its submission, economic Security4Women (eS4W) referred to research

they conducted in 2014 that focused on career guidance and advice provided in

secondary schools. It indicated that there is evidence of gender bias in

existing career counselling resources and approaches.[53]

3.80

NCOSS also gave evidence that:

...through our young women's network (we hear) that at school

there is unconscious bias through the careers counselling process.[54]

Continuing influence of gender

stereotypes—the

example of the STEM sector

3.81

Gender stereotypes are more than a historical hangover. They continue to

be created and propagated and, unless addressed, will lead to a gender

segregated future.

3.82

The under-representation of women in the STEM sector provides a good

case study of the role of social norms and expectations in driving gender

segregation. As a well paid and growing field, it also provides a salient

example of the consequences of gender segregation for the gender pay gap.

3.83

Three quarters of the fastest growing occupational categories requiring

knowledge and skills relate to the STEM sector. However, STEM fields also have

low levels of female employment in Australia, as elsewhere, with around 30 per

cent of graduates being women, less than 30 per cent of jobs being held by

women, and a gender pay gap of around 30 per cent.[55]

3.84

According to the 2016 Global Gender Gap Report:

It represents a key emerging issue for gender parity, since

STEM careers are projected to be some of the most sought-after in the context

of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.[56]

3.85

Since 1987, women have outnumbered men graduating from higher education,

comprising 60 per cent of graduates in recent years, yet less than one in 20

girls considers a career in the high-demand, highly-paid STEM fields compared

to one in five boys, despite girls and boys receiving similar results in the OECD

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) science test.[57]

3.86

This is not just an issue for women; it constitutes a form of labour

market rigidity that constricts Australia’s economy. It is widely recognised

that engaging more women in STEM professions will enhance our capacity to

participate in a rapidly evolving and increasingly competitive global economy.

As Professionals Australia (PA) noted:

A workforce characterised by diversity brings together a

range of people who think differently and approach problems in different ways—and this creates a

“diversity advantage” that generates a range of benefits including a thriving

innovation culture, a positive impact on the bottom line and incentives to

remain in the STEM workforce.[58]

Combatting stereotypes

3.87

A number of submitters suggested ways in which men and women could be

encouraged to combat stereotypes and undertake non-traditional careers.

3.88

The Tasmanian Women's Council (TWC) noted that women's current

underrepresentation in certain occupations can lead to the 'false assumption

that increasing their representation would lower overall productivity':

A further effect ...is, 'you can't be what you can't see'. The

lack of visibility of women in traditionally male-dominated fields (including

as teachers in male-dominated tertiary subjects, particularly STEM) is a

significant contributing factor to ongoing gender segregation in the

workforce.'[59]

3.89

Dr Karen Struthers’ research suggests that female students often know

little about male-dominated trade careers, and may not be confident to pursue

them:

Encouragingly, it seems that more girls would pursue

male-dominated trade careers if they had more experience of them, and more

positive role models and media images of girls in male-dominated roles.[60]

3.90

Although there is a range of information available to promote

non-traditional career choices for girls, several witnesses pointed out that

career guidance materials are fragmented[61]

and varied in accessibility. Existing resources include:

-

the AHRC's Women in Male-Dominated Industries Toolkit providing

strategies to assist employers in attracting women to male-dominated industries and occupations;[62]

-

WGEA's Gender Strategy Toolkit for assisting employers in

achieving gender equality within their organisations;[63]

-

Girls Can Do Anything, a website developed by eS4W, contains

information on role models, career pathways to non-traditional occupations, pay

rates in male-dominated industries, and an explanation of gender-segregated

workforces and the impact that this has on the gender pay gap;[64]

and

-

initiatives being implemented by individual businesses and

organisations such as IBM, Reserve Bank of Australia and Dulux Group to improve

women's participation.[65]

3.91

Some industry-led initiatives are supported by the Australian

Government, including the Australian Women in Resources Alliance e-mentoring

program, which provides mentoring for women in the resources sector to overcome

the barriers of living and working in remote regions. It received Government funding

for a further 100 mentoring places in 2016.[66]

3.92

Allocating responsibility for addressing the under-representation of women

in male-dominated trades is needed.[67]

However, the future shape of the labour market should be taken into

consideration when encouraging more women into traditionally male-dominated

industries:

Encouraging women to further expand supply into male

dominated occupations which are already in relative decline is unlikely to

improve the position of women. Also, if more women enter ‘male’ trades they

will not be entering other occupations which are experiencing relative growth

such as in services and increasingly demanding better-educated women.[68]

Men entering female-dominated

industries

3.93

Few submissions addressed the issue of men's participation in

female-dominated industries, although the DoE pointed to the need to encourage

men to consider growth industries such as health care and social assistance,

which is projected to grow by 250,200 jobs between 2016 and 2020, and education

and training which is projected to grow by 121,700 jobs over the same period and

account for 37.6 per cent of the projected growth.[69]

3.94

A 2014 report prepared by Health Workforce Australia predicted that

Australia’s demand for nurses will significantly exceed supply, with a

projected shortfall of approximately 85,000 nurses by 2025, or 123,000 nurses

by 2030 as a result of population health trends, an ageing nursing and

midwifery workforce, high levels of part-time employment and poor retention

rates.[70]

3.95

The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) provided the

nursing profession as an example of some of the challenges facing the 'caring

professions'. Despite the projected growth in female-dominated caring

professions, it is expected that there will be skills shortages in some of

these professions:

In order to...have a sufficient health workforce that is going

to meet the needs of the community...in the coming decades, we are going to need

a much bigger workforce. A more efficient health workforce is going to be one

that is more nurse-led and less reliant on medical practitioners as the leaders

of the health workforce, but that requires shifts in professional recognition

and acknowledgement...that is going to require a greater workforce overall.

Having more men represented in nursing would assist in achieving both those

things, we believe.[71]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page