Bills Digest No. 46,

2017–18

PDF version [462KB]

Phillip Hawkins

Economics Section

Anna Dunkley and Dr Hazel Ferguson

Social Policy Section

24

October 2017

Contents

Glossary

Table 1: abbreviations and acronyms

Purpose of the Bills

Structure of the Bills

Background

National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding the National Disability

Insurance Scheme

Initial intentions

Current arrangements

National Disability Insurance Scheme

Savings Fund Special Account

Costs and ‘fully-funding’ the NDIS

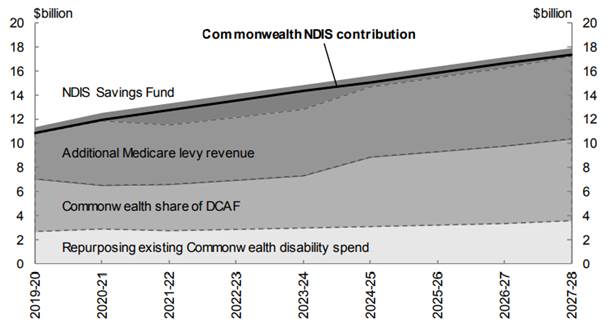

Chart 1: Commonwealth’s NDIS

contribution and funding sources

Hypothecation of taxation

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committee on

Economics

Disability, carer and community

organisations views on the Bill

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Medicare Levy Amendment Bill

Background—Medicare levy

Opposition/minor party views on

increasing the Medicare levy

Financial implications

Commencement

Key provisions

Other Taxation Bills

Commencement

Key provisions

FBT Bill

Income Tax Rates Amendment Bill

Excess Non-Concessional Contributions

Tax Bill

Excess Untaxed Roll-Over Amounts Tax

Bill

TFN Withholding Tax (ESS) Bill

Family Trust Distribution Bill

Trustee Beneficiary Non-Disclosure

(No. 1) Bill

Trustee Beneficiary Non-Disclosure

(No. 2) Bill

Untainting Tax Bill

Nation-building Funds Repeal Bill

Background—the Funds

Building Australia Fund

Education Investment Fund

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Opposition/minor party views on the

abolition of the EIF

Position of major interest groups

Higher Education stakeholder views on

the EIF

Financial implications

Commencement

Key provisions

Appendix A: Education Investment Fund

rounds

Date introduced: 17

August 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Various

dates as set out in this Bills Digest.

Links: The links to the

principal Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website. Links to the other Bills in this package are provided

in the body of this Digest.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at October 2017.

Glossary

Table 1: abbreviations

and acronyms

Purpose of

the Bills

This Bills Digest refers to 11 Bills which make up a suite

of Bills designed to assist in the funding of the National Disability Insurance

Scheme (NDIS).

The principal Bill is the Medicare Levy Amendment

(National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 (the Medicare Levy Amendment

Bill) which amends the Medicare Levy Act

1986 to increase the Medicare levy from 2 per cent to 2.5 per cent.

There are nine related Bills (the Other Taxation

Bills) which amend statutes which provide for tax rates that are linked to the

rate of the Medicare levy or the highest marginal personal income tax rate

inclusive of the Medicare levy. The Other Taxation Bills are:

The Nation-Building

Funds Repeal (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 (the NBF

Repeal Bill) contains an additional measure—the repeal of the Nation-Building Funds

Act 2008 (the NBF Act). The purpose of the NBF Repeal Bill is to

abolish the Building Australia Fund (BAF) and the Education Investment Fund

(EIF). The Government has stated that the uncommitted balances of these funds ‘will

be credited to the National Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special

Account when it is established’.[1]

It is important to note that while the Government states

that these Bills are linked to the funding of the NDIS, the Bills do not

establish a funding mechanism for the NDIS. The National Disability Insurance

Scheme Savings Fund Special Account (the NDIS special account) which is to be

established by the National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill 2016 (the NDIS Special Account Bill) is intended for that

purpose. However, the NDIS Special Account Bill has yet to be passed by the

Parliament.[2]

Structure

of the Bills

The Medicare Levy Amendment Bill has one Schedule which

amends the Medicare Levy Act to increase the Medicare levy rate from two

to 2.5 per cent and make consequential amendments to the Medicare

levy phase-in provisions for low-income families and trusts. The Other Taxation

Bills consist of one Schedule each, amending various statutes to increase taxes

that are linked to the Medicare levy or to the top marginal personal income tax

rate inclusive of the Medicare levy. The amendments to taxation laws are

contained in separate Bills to satisfy the requirements of section 55 of the Constitution

that ‘laws imposing taxation, except laws imposing duties of customs or of

excise, shall deal with one subject of taxation only’.

The NBF Repeal Bill consists of one Schedule divided into

three parts.

Background

National Disability Insurance Scheme

As set out above, the Government has stated that the

additional funding from the Medicare levy increase and the uncommitted funding

from the BAF and the EIF will to be used to assist with funding the NDIS.

The NDIS is a system of government support for eligible people

with disability. It was trialled from July 2013, and is being progressively

rolled out across Australia between 2016 and 2019.[3]

The NDIS was established in response to a campaign for national disability

insurance, and the Productivity Commission (PC) recommendation that Australia

replace the previous ‘underfunded, unfair, fragmented, and inefficient’ system.[4]

The central component of the NDIS is individualised packages

of ‘reasonable and necessary supports’ for eligible people under the age of 65.[5]

The NDIS is also intended to provide all people with disability, their families

and carers with information, links and referrals to disability and mainstream

supports.[6]

The NDIS is not intended to replace these mainstream supports and services,

such as the school education, health and income support systems.[7]

The NDIS was established under the National Disability

Insurance Scheme Act 2013, and is jointly governed and funded by the

Australian and state and territory governments. Like many other social policy

programs—such as Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme—the NDIS is an

uncapped (demand-driven) scheme, and is not means tested.[8]

Funding the

National Disability Insurance Scheme

Initial

intentions

Guaranteed future funding for disability services was part

of the rationale for the NDIS.[9]

The PC noted in its 2011 report that ‘current funding for disability is subject

to the vagaries of governments’ budget cycles’.[10]

It recommended that in order to provide a stable revenue stream ‘the Australian

Government should finance the costs of the NDIS by directing payments from consolidated

revenue into a ‘National Disability Insurance Premium Fund’, using an agreed

formula entrenched in legislation’.[11]

However, the PC also outlined ‘less preferred’ options,

including that the Australian Government could ‘legislate for a levy on personal

income... with an increment added to the existing marginal income tax rates, and

hypothecated to the full revenue needs of the NDIS’.[12]

It also suggested ‘all governments could pool funding, subject to a long-run

arrangement based on... [a] formula, and with pre-specified funding shares’.[13]

In response to the PC report, the Gillard Government

announced that it would ‘start work immediately with states and territories on

measures that will build the foundations for a National Disability Insurance

Scheme’.[14]

Current

arrangements

Following this, the Australian and state and territory

governments created intergovernmental agreements establishing that funding for

the NDIS would be drawn from a combination of sources from all governments.[15]

This included some Australian Government funding previously directed to state

and territory governments for disability services being redirected to the NDIS.[16]

In addition, some funds are being transferred from existing disability programs

and services to the NDIS.[17]

However, governments committed to maintaining continuity of support until the

NDIS is fully implemented, and it appears they will be required to continue

funding ongoing support for people with disability who are not eligible for the

NDIS.[18]

The NDIS is also partly funded from the initial increase

to the Medicare levy, which was raised from 1.5 per cent to 2.0 per cent of

taxable income from July 2014.[19]

The resulting revenue is directed to the DisabilityCare Australia Fund, to be

invested through the Future Fund.[20]

The Australian Government receives approximately two-thirds of the revenue from

the DisabilityCare Australia Fund, and the rest goes to state and territory

governments to partially reimburse their contributions to the NDIS.[21] Other

contributions are funded through general revenue, savings or borrowings.[22]

Arrangements for funding the NDIS are complex, and exact

settings for the full scheme are still under consideration, as outlined in the

PC’s position paper on NDIS costs.[23]

While the amounts provided by state and territory governments will escalate at

an agreed rate, it is predicted the proportion of funding provided by the Australian

Government is likely to grow to more than half of total NDIS funding over time.[24]

Further, the Australian Government is largely responsible for funding cost

overruns, though arrangements were still being finalised as of June 2017.[25]

National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account

The Government proposes to contribute the increased

revenue from the Medicare levy and the uncommitted balances of the BAF and the

EIF to the NDIS Special Account. The NDIS Special Account is to be established

by the NDIS Special Account Bill which was introduced into the House of

Representatives on 31 August 2016 and progressed to the Senate on 20 March

2017. However it has yet to be debated in the Senate.

The NDIS Special Account is a special account under the Public Governance,

Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) with the following purposes

as set out in clause 6 of the NDIS Special Account Bill:

- to assist the Commonwealth to meet its funding obligations in relation

to the NDIS Act

- to make payments to the National Disability Insurance Scheme Launch

Transition Agency (the Agency) for the purposes of the Agency

- to reduce the balance of the Special Account (and, therefore, the

available appropriation for the account) without making a real or notional

payment.[26]

The NDIS Special Account Bill was referred to the Senate

Standing Committee on Community Affairs (Community Affairs Committee) for

inquiry and report.[27]

A number of submitters to the Community Affairs Committee questioned the need

for a special account, particularly in addition to the DisabilityCare Australia

Fund. The rationale for establishing the special account, according to the

Department of Social Services, is to more quickly respond to urgent funding

needs than would be possible from the DisabilityCare Australia Fund and because

the NDIS Special Account is solely for the purpose of meeting the

Commonwealth’s funding requirement, not state expenditures.[28]

Costs and

‘fully-funding’ the NDIS

There is an ongoing debate about whether the initial

funding arrangements for the NDIS were sufficient to cover the full, continuing

costs of the scheme. The Australian Labor Party (Labor) has maintained the ‘NDIS

was fully funded by the former Labor Government in the 2013-14 Budget’.[29]

However, this has been challenged by members of the current Government. For

example, the Minister for Social Services, Christian Porter, has said that ‘the

previous Labor government failed to fully-fund the NDIS, leaving a substantial

funding gap of $3.8 billion for when the scheme is fully operational from

2020’.[30]

Introducing the Medicare Levy Amendment Bill into the House of Representatives,

the Treasurer, Scott Morrison, reiterated this view, declaring ‘[n]ow is the

time to fully fund the NDIS once and for all, and, with this Bill, we will

finally achieve that objective’.[31]

When the NDIS is fully implemented in 2019–20 it is

predicted to cost $22 billion.[32]

Of this, state and territory governments are expected to provide $10.3 billion,

and the rest is to be funded by the Australian Government.[33]

As shown in Chart 1 from the 2017–18 budget papers, the Government has

indicated that funding from the proposed Medicare levy increase from July 2019

will cover the gap it has identified between the sources of funding identified

above and the remaining amount it is obliged to provide under agreements with

the states and territories.[34]

The Government has indicated that the revenue raised through the increase in

the Medicare levy will be directed to the proposed NDIS Special Account.

Chart 1:

Commonwealth’s NDIS contribution and funding sources

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2017–18, p. 3–10.

Given revenue from the Medicare levy is not intended to

meet the full cost of the NDIS, it may not provide the stable revenue stream

originally envisaged by the PC.[35]

Moreover, it is unusual to focus on ‘fully-funding’ a national program such as

the NDIS.

Hypothecation

of taxation

While the Government has stated that the additional

funding from the increase in the Medicare levy and other related taxes and the

uncommitted balances of the BAF and the EIF will contribute to the NDIS Special

Account, the Bills do not create a legal requirement to do so. Rather the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bills states:

One-fifth of the revenue raised by the Medicare levy [the

full, 0.5 per cent increase] from 1 July 2019 will be credited to the National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account ...[36]

Uncommitted funds from the Building Australia Fund and the

Education Investment Fund will subsequently be credited to the National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account when it is established.[37]

It should be noted however, that it is unusual for

significant Commonwealth Government expenditure programs to be funded by taxes

which are hypothecated for that purpose through legislation. The ongoing costs

of the Age Pension, for example, are funded directly from the consolidated

revenue fund as part of the ongoing costs of the Government’s core business. An

example of levies that are hypothecated through legislation for specific

purposes are agricultural levies.[38]

Committee

consideration

Senate

Standing Committee on Economics

The suite of Bills was referred to the Senate Standing

Committee on Economics (Economics Committee) for inquiry.[39]

The Economics Committee released its report on 16 October 2017 and recommended

that the Bills be passed, however the Labor Party issued a dissenting report.[40]

The Economics Committee had received 25 submissions.

The submissions to the Economics Committee were primarily

from disability, care and community organisations who have differing views on

the funding arrangements for the NDIS, and advocates from the higher education

sector expressing concerns about abolition of the EIF. The views of submitters

in relation to the repeal of the EIF are canvassed under the heading

‘Nation-building Funds Repeal Bill’ below.

Disability,

carer and community organisations views on the Bill

Disability, carer and community organisations have

emphasised that ‘secure, sustainable and sufficient long term funding for NDIS’

should not be politicised.[41]

Generally, these groups have expressed support for changing the Medicare levy

to generate funding for the NDIS, and indicated it is preferable to funding the

NDIS through social welfare cuts.

Organisations that have expressed support for the

Government’s proposal include the Australian Federation of Disability

Organisations and the Disability Advocacy Network Australia.[42]

National Disability Services (NDS), the peak industry body for non-government

disability services, has ‘welcomed the Federal Government’s decision to fully

fund its share of the NDIS by increasing the Medicare Levy’.[43]

NDS also noted the Labor Party’s proposal to limit the increase to higher

income earners, and stated it ‘has no view about which tax mix is preferable,

but believes that a political argument over tax equity should not be allowed to

jeopardise the securing of a funding stream for the NDIS’.[44]

The peak body for the community services sector, the

Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS), has also supported amending the

Medicare Levy to raise revenue for the NDIS.[45]

However, ACOSS has proposed the following alternative options for restructuring

the Medicare levy and raising $4 billion ‘in a more progressive way’:

Removing the health insurance exemption from the Surcharge

(as proposed by the Australian Greens); broadening the income ‘base’ of the

Levy to include tax-sheltered income; replacing the Levy and Surcharge with a

Levy with a three-tier tax scale; and replacing them with a Levy based on a

proportion of personal income tax paid each year.[46]

The Disabled People’s Organisations Australia alliance has

supported these proposals from ACOSS.[47]

In contrast, the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation

(ANMF) has opposed ‘[t]ying the Medicare levy to funding the NDIS’, arguing

this ‘risks creating a prejudice among the community that disability is

increasing health care costs without the benefit of providing increased health

services for all’.[48]

Instead, ANMF advocates generating funding for the NDIS by ‘reversing the

corporate tax cut and implementing other reforms’.[49]

Other stakeholders have suggested the debate about

‘fully-funding’ the NDIS should be broadened to consider whether funding the

NDIS is treated as ‘peripheral’ or ‘core’ government business. For example, the

representative groups Children and Young People with Disability Australia

(CYDA) and Young People in Nursing Homes National Alliance (YPINHNA) have

argued:

Because the NDIS will support the realisation of Australia’s

human rights obligations and provide essential services and supports for people

with disability, CYDA and YPINHNA believe it is critical to recognise the

Scheme as a core area of government spending.[50]

YPINHNA further emphasised:

...if the NDIS was a core function of government, there would

be no ‘shortfalls’ as they are conceived in this Bill [the National Disability

Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill 2016]. Core functions of

government do not have ‘accounts’ to ensure their survival and obligations ...

nor should the NDIS.[51]

For these reasons, CYDA and YPINHNA are ‘unable to support

the legislative package’.[52]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had

no comment in relation to the Bills.[53]

Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bills are compatible.[54]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considered

that the Bills do not raise any human rights concerns.[55]

Medicare

Levy Amendment Bill

The Medicare Levy Amendment Bill implements the measure

announced by the Government in the 2017–18 Budget to increase the Medicare levy

from two per cent to 2.5 per cent to assist with funding the NDIS.[56]

The Other Taxation Bills amend other statutes which provide for tax rates that

are linked to the rate of the Medicare levy or the highest marginal personal

income tax rate inclusive of the Medicare levy.

Background—Medicare

levy

The Medicare levy is applied in addition to personal income

tax, currently equal to two per cent of an individual’s total taxable income.

Exemptions from the Medicare levy apply to foreign residents, individuals with

certain medical conditions and individuals not entitled to Medicare benefits.[57]

Low-income individuals, families and pensioners may pay the

Medicare levy at a reduced rate based on their personal[58]

or family income.[59]

Below certain income thresholds, low-income earners pay no Medicare levy. Above

those thresholds the Medicare levy phases-in according to a formula specified

in legislation. The low-income thresholds are higher for pensioners and seniors

who are eligible to receive the Seniors and Pensioners Tax Offset (SAPTO) and

for families with dependent children (the thresholds increase further with the

number of dependents). These income thresholds and the formulas for phasing-in

the Medicare levy are specified in the Medicare Levy Act. The income

thresholds are increased annually through legislation.[60]

The Medicare levy was first introduced in February 1984 to help fund Australia's national health insurance scheme Medicare

and was set at one per cent of taxable income. Since then it has been increased

permanently on a number of occasions to offset increases in medical costs; in

1986 to 1.25 per cent, in 1993 to 1.4 per cent and in 1995 to 1.5 per cent.[61]

It was increased to two per cent in 2013 by the Gillard Government to help fund

the NDIS (at that time called DisabilityCare).[62]

A temporary surcharge to the levy of 0.2 per cent was also applied for one year

in 1996 to help fund the Howard Government’s gun buyback scheme in the wake of

the Port Arthur shootings.[63]

Opposition/minor

party views on increasing the Medicare levy

In its dissenting report on the inquiry into the Bills,

Labor reiterated its proposal to limit the increase in the Medicare levy to

individuals earning over $87,000 and to retain the temporary Budget repair levy

on individuals earning over $180,000.[64]

The Government is reportedly still negotiating the

increase in the Medicare levy with the Australian Greens and other

non-government parties and independents. Senator Derryn Hinch reportedly

supports the proposal.[65]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bills the

increase in the Medicare levy brought about by the Medicare Levy Amendment Bill

and the associated tax changes contained in the Other Taxation Bills will

increase revenue by $8.2 billion over the 2017-18 Budget forward estimates

period.[66]

Commencement

The Medicare Levy Amendment Bill commences on the first 1

January, 1 April, 1 July or 1 October after Royal Assent. The amendments apply

to assessments for the 2019–20 year of income and later years of income.[67]

Key provisions

The Medicare Levy Amendment Bill amends the Medicare

Levy Act. Currently section 6 of the Medicare Levy Act provides that

the rate of the levy payable in specified circumstances is two per cent of

taxable income. Item 1 amends subsections 6(1) to (6) to increase

the Medicare levy tax rate from two to 2.5 per cent in each of those

circumstances, being for individuals[68]

and trustees of trusts,[69]

including managed investment trusts.[70]

Section 7 of the Medicare Levy Act sets the amount

of the levy to be paid in cases of small incomes. Item 2 of the Medicare

Levy Amendment Bill amends subsection 7(4) which currently provides that a

reduced rate of Medicare levy is paid by a trust which has taxable income for a

year of between $416 and $520 per annum. The amendment increases the top of

this band to $555 per annum.

Section 8 of the Medicare Levy Act sets out the

formula for calculating the amount of levy payable by a person who has a spouse

or dependants. Item 3 of the Medicare Levy Amendment Bill amends

subsection 8(2) of the Medicare Levy Act which sets out the calculation

for phasing-in the Medicare levy for low-income families. This provides for a

reduction in Medicare levy based on combined family income within a certain

income range. The lower threshold of this range is called the ‘family income

threshold’.[71]

Above the family income threshold the Medicare levy phases in according to

the formula at subsection 8(2). The formula is amended by the Bill to reflect

the increase in the Medicare levy rate to 2.5 per cent.

The changes in this Bill apply to the 2019-20 income year

and all later income years.

Other Taxation

Bills

Commencement

The Other Taxation Bills commence at the same time as Schedule

1 of the Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Act 2017. However, the provisions do not commence at all if that

Schedule does not commence.

Key

provisions

FBT Bill

The FBT Bill amends the Fringe Benefits Tax

Act 1986 which imposes tax in respect of the fringe benefits taxable

amount of an employer of a year of tax.[72]

Currently the rate of the tax is 47 per cent.[73]

The FBT Bill amends section 6 of the Fringe Benefit Tax Act to increase

the rate to 47.5 percent.

The amendments in the FBT Bill apply to the tax year

starting on 1 April 2019 and all later years of tax, as the FBT year runs from

1 April to 31 March.[74]

Income Tax

Rates Amendment Bill

The Income Tax Rates Amendment Bill amends the Income Tax Rates

Act 1986. Part III of the Income Tax Rates Act sets the rates of

income tax payable upon incomes of companies, prescribed unit trusts,

superannuation funds and certain other trusts. In particular, section 29 sets

the rate of tax payable by:

- a

trustee of a complying superannuation fund in respect of the no-TFN

contributions income of the fund

- a

trustee of a non-complying superannuation fund in respect of the no-TFN

contributions income of the fund and

- a

company that is an Retirement Savings Account provider in respect of no-TFN

contributions income.[75]

Currently the rate of tax payable under the Income Tax

Rates Act is worked out using the formula in subsection 29(2), which

requires as part of the process, the addition of two per cent to a base amount.

The Income Tax Rates Amendment Bill amends that step in the formula by increasing

the additional amount to 2.5 per cent.

Excess

Non-Concessional Contributions Tax Bill

Section 292-80 of the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) provides that a person is liable

to pay excess non-concessional contributions tax imposed by the Superannuation

(Excess Non-concessional Contributions Tax) Act 2007 if the person has

excess non-concessional contributions for a financial year. A person has excess

non-concessional contributions where their non-concessional contributions

exceed the relevant cap, and they elect not to release the amount of the excess

and associated earnings.[76]

The Excess Non-Concessional Contributions Tax Bill amends section

5 of the Superannuation (Excess Non-concessional Contributions Tax) Act to

increase the tax from 47 percent to 47.5 percent of the person’s excess

non-concessional contributions for a financial year.

Excess

Untaxed Roll-Over Amounts Tax Bill

Members of most super funds can request that their super

benefits be transferred into a fund of their choice.[77]

Division 306 of the ITAA 1997 sets out the tax treatment of payments

made from one superannuation plan to another superannuation plan, and of

similar payments.[78]

This is called a roll-over superannuation benefit.[79]

Where a roll-over superannuation benefit includes an element that has been untaxed

—and the amount of the benefit exceeds the person’s untaxed plan cap amount,

the person is liable to tax on the amount of the excess.[80]

The Excess Untaxed Roll-Over Amounts Tax Bill amends

subsection 5(2) of the Superannuation

(Excess Untaxed Roll-over Amounts Tax) Act 2007 so that the formula for

calculating the tax liability includes an increase from two per cent

to 2.5 per cent.

TFN

Withholding Tax (ESS) Bill

Subdivision 14-C of the Taxation

Administration Act 1953 applies where an employer provides one or more

employee share scheme (ESS)[81]

interests under an employee share scheme and the employee has not quoted their

Australian business number or their tax file number to their employer by the

end of the income year. Where this section applies the Income Tax (TFN

Withholding Tax (ESS)) Act 2009 imposes additional income tax on

amounts that are included in a person’s assessable income.

The TFN Withholding Tax (ESS) Bill amends paragraph 4(b)

of the Income Tax (TFN Withholding Tax (ESS)) Act so that the formula

for calculating the additional tax liability includes an increase from two per

cent to 2.5 per cent.

Family

Trust Distribution Bill

The Family Trust

Distribution Tax (Primary Liability) Act 1998 imposes tax that is payable

on the amount or value of income or capital that is assessed under

section 271‑15,[82]

271‑20,[83]

271‑25,[84]

271‑30[85]

or 271‑55[86]

in Schedule 2F to the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA 1936).

Currently the rate of tax is set at 47 per cent. The Family

Trust Distribution Bill amends section 4 of the Family Trust Distribution

Tax (Primary Liability) Act to increase the tax rate to 47.5 per cent.

Trustee

Beneficiary Non-Disclosure (No. 1) Bill

The Taxation (Trustee

Beneficiary Non-disclosure Tax) Act (No. 1) 2007 imposes tax on the

amount payable under paragraph 102UK(2)(a) of the ITAA 1936. Section

102UK relates to the giving of a trustee beneficiary statement in respect of a

specified period.

Currently the amount of the tax is set at 47 per cent. The

Trustee Beneficiary Non-Disclosure (No. 1) Bill amends section 4 of the Taxation

(Trustee Beneficiary Non-disclosure Tax) Act (No. 1) to increase the rate

to 47.5 per cent.

Trustee

Beneficiary Non-Disclosure (No. 2) Bill

The Taxation (Trustee

Beneficiary Non-disclosure Tax) Act (No. 2) 2007 imposes tax on

the amount payable under paragraph 102UM(2)(a) of the ITAA 1936. It

applies where a share of the net income of a closely held trust is included in

the assessable income of a trustee and beneficiary and the share (or part of

it) is income which the trustee of the closely held trust becomes entitled to.

Currently the amount of the tax is set at 47 per cent. The

Trustee Beneficiary Non-Disclosure (No. 2) Bill amends section 4 of the Taxation

(Trustee Beneficiary Non-disclosure Tax) Act (No. 2) to increase the rate

to 47.5 per cent.

Untainting

Tax Bill

The share capital account tainting rules in

the ITAA 1997 are designed to prevent a company from transferring

profits into a share capital account and then distributing these amounts to

shareholders disguised as a non-assessable capital distribution.

If a company's share capital account is

tainted:

- a franking debit arises in the company's franking account at the end of

the franking period in which the transfer occurs

- any distribution from the account is taxed as an unfranked dividend in

the hands of the shareholder

- the account is generally not taken to be a share capital account for

the purposes of the ITAA 1936 and ITAA 1997.

A company's share capital account remains

tainted until the company chooses to untaint the account. The choice to untaint

a company's share capital account can be made at any time, but once the choice

is made it cannot be revoked.[87]

Where the company chooses to untaint the account an untainting

tax is payable. Section 197-60 of the ITAA 1997 sets out the formula for

calculating the amount of an untainting tax which is payable. The Untainting

Tax Bill amends subsection 197-60 to increase the applicable tax rate by 0.5

per cent.

With the exception of the amendments in the FBT Bill, the

taxes affected by the Other Taxation Bills apply from 1 July 2019, or

the 2019–20 income year and all later income years.

Nation-building

Funds Repeal Bill

The NBF Repeal Bill implements the Government’s

announcement in the 2016–17 Mid-year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) that

it would use the uncommitted funds in the BAF and the EIF to assist with

funding the NDIS and reducing Commonwealth debt.[88]

Background—the

Funds

The NBF Repeal Bill repeals the NBF Act. The NBF

Act as enacted established three Funds—the BAF, the EIF and the Health and

Hospitals Fund.[89]

The balance of the Health and Hospitals Fund was transferred into the Medical

Research Future Fund with the enactment of the Medical Research Future Fund

Act 2015.[90]

Initial funding for the BAF was around $2.5 billion from

the Communications Fund and $966 million from the Telstra Sale Special Account.[91]

Initial funding for the EIF was around $6.5 billion from the balance of the Higher

Education Endowment Fund (HEEF), which had been established in 2007 and was

being replaced by the new Fund.[92]

Ongoing funding for the BAF and the EIF was intended to come from Commonwealth

Budget surpluses and Fund investments. In total, $12.5 billion from the 2007-08

Budget surplus was credited to the Nation-building Funds, including $7.5

billion to the BAF and $5 billion to the Health and Hospitals Fund.[93]

However, with the Budget going into deficit from 2008–09, this was the only

year that funds from surpluses were credited to the Nation-building Funds.[94]

In 2014, the National Commission of Audit (NCOA) suggested

‘the Government may wish to re-examine the need for the Nation-building funds

in their current form’. The NCOA identified:

A weakness in current infrastructure funding arrangements

between the Commonwealth and the States is that Commonwealth funding is

generally focused on investing in new projects...

The current arrangements for the three Nation-building Funds,

with funding only able to be directed to capital expenditure, leads to an undue

emphasis on ‘ribbon cutting’ opportunities generally associated with new

projects, at the expense of periodic maintenance and of small-scale

improvements that could postpone or even avoid the need for costly asset

expansions.[95]

In the subsequent 2014–15 Budget, the Government announced

the BAF and the EIF would be abolished and the unallocated funds transferred to

the Asset Recycling Fund (ARF), with existing EIF projects to continue to

receive funding according to their funding agreements.[96]

Accordingly, the Asset Recycling Fund Bill 2014 was introduced

into the House of Representatives on 29 May 2014. However, the Bill lapsed

when the Parliament was prorogued on 15 April 2016.

The rationale for the repeal of the NBF Act is to

redirect the uncommitted balance of the BAF and the EIF to the NDIS Special

Account. As at 30 June 2017, the uncommitted balance of the BAF is $3.79

billion and the uncommitted balance of the EIF is $3.79 billion, with a current

total of $7.57 billion.[97]

Building

Australia Fund

The BAF is a Special Account for the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act). It was established on 1 January 2009 by section

12 of the NBF Act ‘to finance capital investment in

transport infrastructure (such as roads, rail, urban transport and ports),

communications infrastructure (such as broadband), energy infrastructure and

water infrastructure’.[98]

Infrastructure Australia evaluates projects

and provides advice to Government Ministers on proposals to be funded from the

BAF. Infrastructure Australia is required to evaluate projects against the BAF

Evaluation Criteria which includes assessing the

extent to which projects address national infrastructure priorities and are

justified by available evidence and data (including cost-benefit analysis).[99] Since its inception the

BAF has contributed a total of $9.8 billion to approved projects[100] including $2.4 billion

for the National Broadband Network, $3.2 billion in Victoria for regional

rail and $1.5 billion for the Hunter Expressway in NSW.[101]

Education

Investment Fund

The EIF is also a Special Account for the purposes

of the PGPA Act. It was established on 1 January 2009 by section 131 of

the NBF Act to provide dedicated ongoing

capital funding for tertiary education and research infrastructure.[102]

The EIF was established by the Rudd Labor Government in response to concerns

about the sector’s unmet infrastructure needs, including a maintenance backlog

and increased demand for contemporary learning and research spaces.

Base funding for universities is provided through a

combination of the Commonwealth Grant Scheme and the Higher Education Loan

Program (HELP) to meet the basic costs of university learning and teaching

provision. This includes ‘a notional amount to meet the costs of

infrastructure’. However, according to estimates prepared for the higher education base funding review

report, universities had unaddressed maintenance needs estimated to be

between $2.08 billion to $3.19, while growing student numbers and increased

emphasis on competitive research excellence increased pressure for new or

refurbished buildings and other facilities.[103]

The EIF was therefore intended to provide a large-scale funding source for transformational

projects which would allow Australian research and tertiary education

institutions to compete effectively with international counterparts.[104]

Funding rounds for the EIF were held between 2008 and 2011

to resource a range of projects according to need and government priorities (a

list of funding rounds is provided at Appendix A). Responsible Ministers made

recommendations for funding projects to the Prime Minister based on advice from

the EIF Advisory Board against the EIF Evaluation

Criteria.[105]

Over $4

billion of projects were supported, including the

Transformation of Central Queensland University into a dual sector

institution, a Joint

Health Education Facility at Port Macquarie, the Australian Centre for Indigenous

Knowledge and Education, and Australia’s involvement in the Giant Magellan Telescope project.[106]

The importance of ongoing funding akin to

what had been provided by the EIF was emphasised in September 2015, when the final report of

the Research Infrastructure Review found ‘[t]here is

considerable concern about successive governments’ practice of funding long

term investments on short term funding cycles’.[107] The report recommended

the Australian Government:

...commit $3.7 billion funding [remaining from

the EIF] for the Australian National Research Infrastructure Fund within the

Infrastructure Growth Package and the Asset Recycling Fund ... [and suggested] in

all the circumstances, there are good arguments for a proposal to use the EIF

balance for investment in National Research Infrastructure. It is the right

amount, the funds are not being used productively and the proposal is

consistent with the original intended use of the funds.[108]

While the EIF was not exclusively concerned with research

infrastructure, its loss would represent a loss of ongoing capital funding,

which to date, funding to maintain National

Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) facilities under the

National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA), and the National

Research Infrastructure Roadmap have not addressed.[109]

In 2016, the final report of the Higher

Education Infrastructure Working Group, which was established to advise the

Government on the options available to the higher education sector in relation

to teaching and research infrastructure, found that capital grants accounted

for a higher than usual proportion of higher education infrastructure

investment from 2011 to 2013 (when large-scale EIF funding was being rolled

out) and also allowed institutions to leverage this funding to invest in a

range of significant projects with partner organisations. Yet it also

identified that capital grants, while more significant than usual during this

time period, still accounted for only 18 per cent of infrastructure spending,

with the majority of investment coming from institutions’ cash operating

surpluses. However, the Working Group observed:

...[w]hile most universities have been well

placed to fund their infrastructure investments, there are a small number of

institutions that have clearly struggled... Smaller regional universities, in

particular, were more dependent on capital grants for infrastructure

investment. As a result they will face particular challenges adjusting their

operations to either accumulate the surpluses necessary to internally finance

future infrastructure, particularly large scale building construction and

renewal, or to service substantial debt.

With the loss of the Higher Education Endowment Fund (HEEF)

and the Education Investment Fund (EIF), established to assist universities to

build world class transformative facilities, we have lost something which was

designed to take our institutions to another level.[110]

Thus, the proposed abolition of the EIF appears to

finalise the process of shifting ongoing responsibility for capital funding for

higher education infrastructure to institutions, raising concerns in particular

about the capacity of smaller and rural tertiary education providers and those

with concentrations of research excellence in fields that rely on expensive

specialist facilities and equipment to meet their infrastructure needs.[111]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Opposition/minor

party views on the abolition of the EIF

Labor opposes the abolition of the EIF as a cut to higher

education funding:

We're not going to support their plans to abolish the

Education Investment Fund. If you compare the approach of Labor governments

over decades to higher education to that of the coalition, the Liberal and

National parties, you see the world through the prism of privilege. They vote

accordingly. Others see the world through the prism that higher education is an

opportunity to improve your lot in life. We put in place the Education

Investment Fund, which improved the facilities of universities right around the

country, particularly in regional campuses around the country, where millions

and millions of dollars was invested, including in my own campus at Wollongong.

Millions and millions of dollars was invested. What is this government

attempting to do? Abolish that fund so that those funds aren't available to

invest in university facilities around the country.[112]

The Jacqui Lambie Network also opposes the abolition of

the EIF as a cut to higher education funding:

Now the government is looking to slash another $3.8 billion

from the Education Investment Fund, from infrastructure funding. The

government's rhetoric that universities can afford these cuts because they are

all profiting is an absolute joke. Universities do not profit. When a

university is lucky enough to post a surplus, it is invested in research

infrastructure or student support programs.[113]

Position of

major interest groups

As stated above, many of the submissions to the Economics

Committee inquiry into the Bills were from the higher education sector

expressing concerns about abolition of the EIF.

Higher

Education stakeholder views on the EIF

Higher education stakeholders have reacted strongly against

the proposed abolition of the EIF, with Universities Australia Chief Executive

Belinda Robinson stating:

Without Commonwealth funding for new and refurbished

education buildings, future students, communities and the nation will see a

gradual erosion of our world-class university facilities.[114]

While peak bodies from the higher education sector that

have engaged directly with the question of funding the NDIS are supportive of

the Scheme, they are uniform in their rejection of the EIF as a source of

funding. Many raise concerns about the impact on Australia’s learning, teaching

and research capacity and international competitiveness, and point out that the

EIF was intended to provide funding stability for transformational

infrastructure, and should be used for that purpose in light of other

Government priorities such as the NISA. For example, the Group of Eight (Go8)

submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics inquiry into the Bills

calls the loss of the EIF ‘devastating’, saying the remainder of the fund

should be directed towards ongoing funding for capital investment in research

infrastructure:

The Go8 strongly supports the appropriate and effective

funding of the NDIS. However, Governments have choices in how to fund such

landmark schemes. The Go8 contends that the Government can exercise its option

not to use the remaining EIF funds for this purpose, in view of the devastating

impact the loss of the EIF will have on the nation’s research capability. The

use of EIF, conversely, to alleviate the cost of the NDIS can only have a

temporary, short-term and relatively insignificant impact on the scheme’s

budget...Our international competitiveness and reputation in higher education

provision and as a research nation will be placed at risk. Benefits to

industry, the Government’s Industry portfolio and innovation agenda, and other

functions and priorities of government will be compromised. The loss of the EIF

will significantly further compromise the higher education sector if compounded

by the cuts to university funding proposed under the Government’s Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (A More Sustainable, Responsive and Transparent

Higher Education System) Bill 2017.[115]

Concerns related to regional and smaller institutions are

also raised in a number of submissions. Although the Regional Universities

Network (RUN) did not make a submission to the inquiry, it has indicated elsewhere

that it shares the concerns expressed by the Higher

Education Infrastructure Working Group about the capacity of some

institutions to invest in infrastructure, despite the overall positive position

of the sector:

Smaller universities have difficulty in generating sufficient

cash surpluses to invest in larger scale infrastructure projects to assist them

in adapting to local market conditions, improve their long-term viability and

enhance the student experience. Finding funding to address deferred maintenance

is also an issue. Coupled with this, less “elite” and younger universities are

less able to attract substantial philanthropic funding, either to fully fund or

co-invest in major teaching and/or research projects. The Education

Infrastructure Fund (EIF) and the Structural Adjustment Fund (SAF) provided

significant infrastructure funding to regional universities which would not

have been otherwise available. Increasingly, universities need to invest in

their IT infrastructure. This is partly to meet student expectations about

flexible modes of delivery, as well as multiple locations and a substantial

number of students studying externally. Investment in IT infrastructure is a

regular call on an institution’s funds, and can be exacerbated by uncertainty

of future teaching methods. IT can be difficult to obtain external borrowings

for this type of investment as there is no physical asset to back the security.[116]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bills the

closure of the BAF and the EIF as part of the 2016–17 MYEFO measure Asset

Recycling Fund – not proceeding will increase revenue by $81 million over

the 2016–17 Budget forward estimates period. $7.2 billion is expected to be

contributed to the NDIS special account from the uncommitted balances of the

BAF and the EIF.[117]

Commencement

The NBF Repeal Bill commences on the earliest of a single

day fixed by proclamation, or six months after Royal Assent.

Key

provisions

The Nation-building Funds Repeal Bill consists of one

schedule with three parts. It has the primary purpose of repealing the Nation-building

Funds Act.

Part 1 repeals the Nation-building Funds Act

in its entirety, thereby abolishing both the BAF and the EIF.

Part 2 makes consequential amendments to a number

of Acts which refer to the NBF Act, primarily removing references to the

NBF Act in other Commonwealth Acts.

Items 2 to 4 amend the COAG Reform Fund

Act 2008 to remove references to the NBF Act.

Items 5 to 6 amend the DisabilityCare Australia

Fund Act 2013 to remove references to the NBF Act.

Items 7 to 28 amend the Future Fund Act 2006 to

remove references to the NBF Act.

The Future Fund Board of Guardians has responsibility for

managing the investments of the Building Australia Fund and the Education

Investment Fund in accordance with the funds’ investment mandates.[118]

The proposed amendments to the Future Fund Act will abolish the Board’s

responsibilities in respect of these funds.

Item 29 amends the Health Insurance Act 1973

to note the NBF Act is repealed.

Item 30 to 33 amend the Medical Research Future

Fund Act 2015 to note that the NBF Act is repealed.

Part 3 outlines the transitional provisions for

the NBF Repeal Bill.

Item 34 maintains the right for the Finance

Minister to require the Future Fund Board to prepare reports or provide

information on matters relating to the BAF and the EIF.

Item 35 maintains that any agreement under section

179 of the NBF Act that is in place prior to the repeal of the NBF

Act continues in force. Section 179 relates to grants made from the EIF to

a person other than a state or territory. However, the Minister who administers

the Higher Education Support Act 2013 may vary or revoke such an

agreement.

Section 63 of the Future Fund Act provides

protection from civil and criminal liability for the Board members (including

the Chair) of the Future Fund in relation to acts that they are required to do

under relevant legislation. Section 63 is amended by item 16 to remove

references to the NBF Act. Item 36 provides that, despite the amendment

made by item 16, Board members retain protection for acts required by the NBF

Act that they performed prior to the amendment commencing.

Item 37 provides that the Board of the Future Fund

will continue to be required to provide information on debits from the BAF and

the EIF in its annual report to the Minister.

Item 38 provides that miscellaneous amounts received

by the Board of the Future Fund for the BAF or the EIF are not required to be

credited to the Future Fund. The note to item 38 indicates that these amounts

will form part of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

Item 39 allows the Minister to make transitional

rules by legislative instrument that relate to amendments in the NBF Repeal

Bill. However the Minister may not create an offence or civil penalty, provide

powers of arrest or detention, entry or seizure, impose a tax, appropriate

amounts from consolidated revenue or directly amend the text of the NBF Repeal

Act (when enacted).

Appendix A:

Education Investment Fund rounds

The following Education Investment Fund funding rounds

were held between 2008 and 2011:

- round

one competitive funding of $580 million announced in 2008

- a

Teaching and Learning Fund of $500 million announced in 2008, distributed to eligible

universities based on domestic student load for building and upgrades of

teaching and learning spaces

- round

two competitive funding of $934.2 million announced in 2009

- the

Super Science Initiative, which provided non-competitive funding of $989.4 million

announced in 2009 to address space science and astronomy, marine and climate

science, and future industries, three of the priorities identified in the Strategic

Roadmap for Australian Research Infrastructure

- round

three competitive funding and the competitive Sustainability Round, totalling

$550 million in 2010

- a

$300 million contribution to the Clean Energy Initiative to support the Solar

Flagship and Carbon Capture and Storage Flagship programs launched in 2009

- a

Structural Adjustment Round launched in 2010, which allocated $200 million for

infrastructure projects associated with adaptation to the demand driven funding

system for domestic undergraduate university places

- a

Regional Priorities Round of $500 million competitive funding to support regional

institutions, launched in 2011.[119]

[1]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Bill 2017 [and related Bills], p. 4.

[2]. P

Pyburne, National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill 2016,

Bills digest, 1, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2016.

[3]. NDIS,

About

the NDIS, NDIS, p. 2.

[4]. Productivity

Commission (PC), Disability care

and support, Inquiry report, 54, PC, Canberra, 2011, vol. 1, p. 2.

[5]. L

Buckmaster, The

National Disability Insurance Scheme: a quick guide, Research paper

series, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, updated 3 March 2017, p. 1.

Much of this section of the Bills Digest is sourced from this research paper.

[6]. NDIS,

About

the NDIS, op. cit., p. 2.

[7]. NDIS,

The

NDIS and mainstream interfaces, NDIS, 16 January 2014.

[8]. Buckmaster,

The

National Disability Insurance Scheme: a quick guide, op. cit., p. 1.

[9]. L

Buckmaster and A Dunkley, ‘Fully

funding’ the NDIS, in Budget review 2017–18, Research paper series,

2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 19 May 2017, p. 112.

[10]. PC,

Disability care and support,

op. cit., vol. 1, p. 3.

[11]. PC,

Disability care and support,

op. cit., vol. 2, p. 637.

[12]. PC,

Disability care and support,

op. cit., vol. 1, p. 85.

[13]. PC,

Disability care and support,

op. cit., vol. 2, p. 637.

[14]. J

Gillard (Prime Minister), Productivity

Commission's final report into disability care and support, media

release, 10 August 2011.

[15]. NDIS,

‘Intergovernmental

agreements’, NDIS website.

[16]. PC,

National

Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) costs, position paper, June 2017, p.

328.

[17]. Senate

Community Affairs Committee, Answers to Questions on Notice, Social Services

Portfolio, Supplementary Estimates Hearings 2016–17, Question

No: SQ16-000402; NDIA, Submission to

the Joint Standing Committee on the NDIS, Inquiry regarding the

provision of services under the NDIS for people with psychosocial disabilities

related to a mental health condition, 2017, p. 5.

[18]. A

Dunkley, ‘Mental

health’, Budget review 2017–18, Parliamentary Library, Canberra,

2017, p. 73; Department of Health, Prioritising

mental health—psychosocial support services—funding, The Department,

Canberra, 2017.

[19]. J

Gillard (Prime Minister) and W Swan (Treasurer), Medicare

Levy increase to fund DisabilityCare Australia passes the Parliament,

media release, 16 May 2013; Parliament of Australia, Medicare

Levy Amendment (DisabilityCare Australia) Bill 2013 homepage, Australian

Parliament website.

[20]. PC,

National

Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Costs, op. cit., p. 329; Australian

Government, ‘DisabilityCare

Australia Fund Financials webpage’, Department of Finance website, 18

October 2017; DisabilityCare

Australia Fund Act 2013 (Cth).

[21]. The

amount received by state and territory governments from the DisabilityCare

Australia Fund will increase at 3.5 per cent each year until 2023–24. PC, National Disability

Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Costs, op. cit., pp. 328–9, 335.

[22]. L

Buckmaster, The

National Disability Insurance Scheme: a quick guide, op. cit., p. 4.

[23]. PC,

National

Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) costs, op. cit., chapter 10.

[24]. Ibid.,

pp. 47, 333–4.

[25]. Ibid.,

p. 327.

[26]. Pyburne,

National

Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill 2016, op.

cit., p. 6.

[27]. The

terms of reference, submissions to the Committee on Community Affairs and the

final report are available on the inquiry

homepage.

[28]. Senate

Community Affairs Legislation Committee, National Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill

2016 [Provisions], 7 November

2016, p. 11.

[29]. J

Macklin (Shadow Minister for Families and Social Services), Morrison

can’t hold the NDIS to ransom again, media release, 9 May 2017.

[30]. C

Porter (Minister for Social Services), Z Seselja (Assistant Minister for Social

Services and Multicultural Affairs) and J Prentice (Assistant Minister for

Social Services and Disability Services), Guaranteeing

the NDIS and providing stronger support for people with disability, joint

media release, 9 May 2017.

[31]. S

Morrison, ‘Second

reading speech: Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Bill 2017’, House of Representatives, Debates, 17 August

2017, p. 8825.

[32]. PC,

National

Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) costs, op. cit., p. 323.

[33]. Ibid.

[34]. Australian

Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2017–18, pp. 3–9.

[35]. Buckmaster

and Dunkley, ‘Fully funding’ the NDIS,

op. cit., p. 113.

[36]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Bill 2017 [and related Bills], p. 8.

[37]. Ibid,

p. 4.

[38]. For

example, levies under the Primary Industries

(Excise) Levies Act 1999.

[39]. The

terms of reference, submissions to the Committee on Economics and the final

report are available on the inquiry

homepage.

[40]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Medicare

Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

related bills [provisions], The Senate, Canberra, 16 October 2017, pp.

26–27.

[41]. Disabled

People’s Organisations (DPO) Australia, Australian Federation of Disability

Organisations (AFDO) and Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS), We

call on this Parliament to deliver secure, sustainable and sufficient funding

for the National Disability Insurance Scheme, media release, 23 July

2017.

[42]. AFDO,

Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10 Related

Bills [Provisions], September 2017; G Chan, ‘Labor

using NDIS and Medicare levy “to play politics”, disability groups say’, The

Guardian, 15 May 2017.

[43]. National

Disability Services, Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy Amendment

(National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10 Related Bills

[Provisions], September 2017.

[44]. Ibid.

[45]. ACOSS,

Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

Related Bills [Provisions], 7 September 2017.

[46]. Ibid.,

pp. 1, 19.

[47]. DPO

Australia, Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

Related Bills [Provisions], September 2017, p. 3.

[48]. Australian

Nursing and Midwifery Federation, Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

Related Bills [Provisions], September 2017, p. 2.

[49]. Ibid.,

p. 3.

[50]. Children

and Young People with Disability Australia (CYDA) and Young People in Nursing

Homes National Alliance (YPINHNA), Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

Related Bills [Provisions], September 2017, p. 5.

[51]. YPINHNA,

Submission

to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs, Inquiry into the

National Disability Insurance Scheme Savings Fund Special Account Bill 2016,

October 2016, pp. 2–3.

[52]. CYDA

and YPINHNA, Submission

to Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare Levy

Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

Related Bills [Provisions], op. cit., p. 2.

[53]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 10,

2017, The Senate, Canberra, 6 September 2017, p. 19.

[54]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at pages 18-24 and

page 31 of the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bills.

[55]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Scrutiny

report, 9,

2017, 5 September 2017, p. 83.

[56]. Australian

Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2017–18, pp. 24–25.

[57]. Australian

Taxation Office (ATO), 'Medicare

levy exemption’, ATO website, last modified 7 July 2017.

[58]. ATO,

‘Medicare

levy reduction for low income earners’, ATO website, last modified 29 June

2017.

[59]. ATO,

‘Medicare

levy reduction – family income’, ATO website, last modified 29 June 2017.

[60]. For

example, the Treasury

Laws Amendment (Medicare Levy and Medicare Levy Surcharge) Act 2017.

[61]. A

Biggs, 'A

short history of increases to Medicare levy’, FlagPost, Parliamentary

Library blog, 3 May 2013.

[62]. Parliament

of Australia, ‘Medicare

Levy Amendment (Disability Care Australia) Bill 2013 homepage’ Australian

Parliament website.

[63]. Biggs,

op. cit.

[64]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Inquiry

into the Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability

Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10 related bills, The Senate, Canberra, 16 October 2017, p. 27.

[65]. C

Gribbin, ‘Bill

to hike Medicare levy to raise $8 billion NDIS funding set to face Parliament’,

ABC News online, 17 August 2017.

[66]. Explanatory

Memorandum Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Bill 2017 [and related Bills], p. 4.

[67]. Item

4 of the Medicare Levy Amendment Bill.

[68]. Medicare

Levy Act, subsection 6(1).

[69]. Medicare

Levy Act, subsections 6(2) and 6(3).

[70]. Medicare

Levy Act, subsections 6(4)-(6).

[71]. The

family income threshold is set under subsections 8(5)-8(7) of the Medicare

Levy Act and is currently $36,541 (or $47,670 if the individual is eligible

for SAPTO) and increases by $3,356 per dependent.

[72]. Fringe

Benefits Tax Act, section 5.

[73]. Fringe

Benefits Tax Act, section 6.

[74]. ATO,

Fringe benefits tax – rates and

thresholds, ATO website, last modified 15 September 2017.

[75]. Section

295-610 of the Income

Tax Assessment Act 1997 provides that no-TFN contributions

relate to contributions to a superannuation fund by a person who has not

provided the fund with their Tax File Number.

[76]. The

cap is set by Subdivision 292-C of the ITAA 1997.

[77]. Australian

Taxation Office (ATO), ‘Receiving

member roll-over requests’, ATO website, last modified 8 September 2015.

[78]. ITAA

1997, section 306-1.

[79]. ITAA

1997, section 306-10.

[80]. ITAA

1997, section 307-350 sets out the cap amount.

[81]. ITAA

1997, section 995-1.

[82]. Tax

liability where family trust makes distribution outside a family group.

[83]. Tax

liability where interposed trust makes distribution outside a family group.

[84]. Tax

liability where interposed partnership makes distribution outside a family

group.

[85]. Tax

liability where interposed company makes distribution outside a family group.

[86]. Notice

requiring information about non-resident distributions.

[87]. Australian

Taxation Office (ATO), ‘Share

capital account tainting’, ATO website, last modified 1 December 2016.

[88]. S

Morrison (Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2016-17, December 2016, p. 157.

[89]. R

Webb, C Dow and R de Boer, Nation-building

Funds Bill 2008, Bills digest, 67, 2008–09, Parliamentary Library,

Canberra, 2008.

[90]. J

Murphy and D Brett, Medical

Research Future Fund Bill 2015 [and] Medical Research Future Fund

(Consequential Amendments) Bill 2015, Bills digest, 3, 2015–16,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2015.

[91]. Nation-building

Funds Act 2008 (as made), sections 16 and 17.

[92]. Nation-building

Funds Act 2008 (as made), section 133; Nation-building

Funds (Consequential Amendments) Act 2008.

[93]. Department

of Finance (DoF), Nation-building funds financials, DoF website,

last updated 18 October 2017.

[94]. Senate

Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry

into the Nation-building Funds Bill 2008 [Provisions], Nation-building

Funds (Consequential Amendments) Bill 2008 [Provisions] and COAG Reform Fund

Bill 2008 [Provisions], The Senate, Canberra, 2008, pp. 1–2, accessed

13 September 2017.

[95]. National

Commission of Audit, Towards

responsible government, Phase 2, section 2.4 Commonwealth funding to state

and local governments for infrastructure, 2014, pp. 31–32.

[96]. Australian

Government, Budget measures:

budget paper no. 2: 2014–15, p. 114–115.

[97]. Department

of Finance (DoF), Nation-building funds financials, DoF website,

last updated 18 October 2017.

[98]. DoF,

‘Nation

building funds: building Australia fund’, DoF website, last updated 18

October 2013.

[99]. BAF Evaluation

Criteria

[100]. DoF,

Building

Australia Fund – approved projects, DoF website.

[101]. National

Commission of Audit, op. cit., p. 31.

[102]. Section

131, Nation-building

Funds Act 2008 (Cth); Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), Agency management of special accounts,

Audit report, 24, 2003–04, ANAO, Barton, ACT, 2004; Department of Finance, ‘Special

appropriations: special accounts’, DoF website, provides the following

definition: ‘A special account is a limited special appropriation that

notionally sets aside an amount that can be expended for listed purposes. The

amount of appropriation that may be drawn from the CRF [Consolidated Revenue

Fund] by means of a special account is limited to the balance of each special

account at any given time.’ The EIF Special Account is operated through two

Portfolio Special Accounts, the EIF Education Portfolio Special Account and the

EIF Research Portfolio Special Account.

[103]. Higher Education Base Funding Review [Panel]: final report, [Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations,

Canberra], 2011, p. 45 and 84–85.

[104]. Australian

National Audit Office (ANAO), Administration

of Grants from the Education Investment Fund: Department of Industry,

Innovation, Climate Change, Science, Research and Tertiary Education,

Audit report, 37, 2012–13, ANAO, Barton, ACT, 2013.

[105]. Ibid.

[106]. Finance,

‘Education

investment fund – approved projects’, Finance website; Central Queensland

University (CQ University), ‘Dual

sector university decision will transform central Queensland’, CQ

University website; University of New South Wales, Sydney (UNSW Sydney), ‘Joint

health education facility – Port Macquarie: expanding medical education

opportunities in regional Australia’, UNSW Sydney website; Charles Darwin University (CDU), ‘Australian Centre for Indigenous Knowledge

and Education’, CDU website; Australian Giant Magellan Project Office, ‘Giant Magellan telescope

information’, Australian Giant Magellan Project

Office website.

[107]. Research

Infrastructure Review, Research

Infrastructure Review: final report, 10 September 2015, p. 3.

[108]. Ibid.,

pp. viii, 30 and 32.

[109]. Department

of Education and Training (DET), ‘National collaborative research infrastructure strategy (NCRIS)’, DET website; Department of Education and Training (DET), ‘2016 National research infrastructure roadmap’,

DET website, last modified 12 May 2017.

[110]. Research

Infrastructure Review, Research

Infrastructure Review: final report, op. cit., pp. 18–21.

[111]. While

the trend toward ‘roll in’ of infrastructure funding for learning and teaching

purposes has been long-running, the opposite trend has emerged in research

funding, with the need to address the cross-subsidisation of research from

learning and teaching. A history of government capital infrastructure funding

is provided at pp.40–42 of P M Clark, Research Infrastructure

Review: final report, Department of Education and Training, Canberra, 5

September 2015.

[112]. S

Jones, ‘Second

reading speech: Higher Education Support Legislation Amendment (A More

Sustainable, Responsive and Transparent Higher Education System) Bill 2017,’

House of Representatives, Debates, 12 September 2017, p. 10,086.

[113]. J

Lambie, ‘Questions

without notice: higher education’, Senate, Debates, 12 September

2017, p. 6957.

[114]. Universities

Australia (UA), ‘We

can’t afford to lose the education investment fund’, UA website, 23

February 2017.

[115]. Group

of Eight (Go8), Submission

to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Inquiry into the Medicare

Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme Funding) Bill 2017 and 10

related bills [provisions], 8 September 2017, pp.2–3.

[116]. Regional

Universities Network (RUN), ‘Submission

to driving innovation, fairness and excellence in Australian higher education’,

2016, p. 9, RUN website.

[117]. Explanatory

Memorandum Medicare Levy Amendment (National Disability Insurance Scheme

Funding) Bill 2017 [and related Bills], p. 5.

[118]. Future

Fund, ‘Our funds’,

Future Fund website.

[119]. Summarised

from ANAO, Administration

of Grants from the Education Investment Fund, Audit report, 37,

2012–13, ANAO, Barton, ACT, 2013, p. 114. The 2008 round was funded from the EIF,

and is often referred to as the first round of EIF funding, however the round

was launched and assessed under the predecessor Higher Education Endowment

Fund Act 2007. A full account of the EIF funding components prepared by the

Department of Finance is available at Finance, ‘Education

investment fund – approved projects’, Finance website.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.