Bills Digest no. 41,

2016–17

PDF version [832KB]

James Griffiths

Social Policy Section

22

November 2016

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Structure of the Bills Digest

Commencement

Purpose of the Bills

Structure of the Bill

Background

A complicated policy landscape

The legislative framework

The regulatory space

Program and funding flows

Intergovernmental agreements

Australian government programs

State and territory government

programs

Policy design and responsibility

The VET FEE-HELP Scheme

Development

Reforms to expand the VET system

Emerging issues with VET FEE-HELP

Government responses and further

scrutiny

A new model for VET FEE-HELP

Committee consideration

Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Special appropriations

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Overview

The unclear purpose of VET

Eligible students

Approved courses

Approved course providers

The design of the VET market

The use of listed providers

VET and higher education

The effectiveness of regulation

A new regulatory regime – more of the

same?

Regulatory capacity

Inputs and outcomes

Administrative complexity and the VET

system

The cost of education

The cost to government

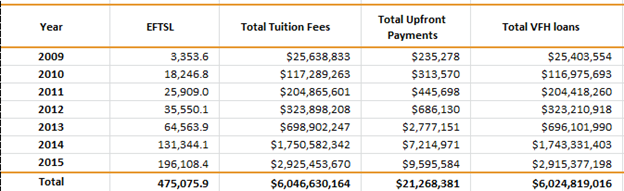

Table 1: Fees and loans time series

(2009–2015)

Concluding comments

What now for the VET FEE-HELP model?

Date introduced: 13

October 2016

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Education

and Training

Commencement: For

commencement details see page 5 of this Digest.

Links: The links to the Bills,

their Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speeches can be found on the

Bills’ home pages for the VET

Student Loans Bill 2016, the VET

Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016, and the VET

Student Loans (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill

2016, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2016.

The Bills Digest at a glance

What the Bills are

This Bills Digest relates to three Bills being:

- the VET Student Loans Bill 2016 (the Student Loans Bill)

- the VET Student Loans (Consequential Amendments and Transitional

Provisions) Bill 2016 (the Consequential Amendments Bill) and

- the VET Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016 (the Charges Bill)

Background

- The Bills result from a 2015 policy commitment to reform the VET

FEE-HELP scheme. The administration and fiscal sustainability of VET FEE-HELP

has been subject to criticism and media attention since 2014.

Key elements

- The Student Loans Bill is based around three concepts: that of

the eligible student, the approved course, and the approved

course provider. These are intended to ensure that vocational education

and training (VET) student loans are directed to those students who are most

likely to benefit from financial support.

- The Minister will be able to set a loan cap for each eligible

course, limiting the amount of financial assistance the government is able to

offer eligible students in these courses.

- VET student loans will be treated as FEE-HELP debts in line with

the existing Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) under the Higher Education

Support Act 2003. Students will be required to repay their loan debts

through the taxation system when their income reaches a set HELP threshold.

- To improve the oversight of the scheme, the Student Loans Bill grants

monitoring and enforcement powers to the Department of Education and Training

that are more extensive than those under the existing VET FEE-HELP scheme or

other HELP loans schemes. A civil penalty regime will also apply in cases of

non-compliance.

Stakeholder concerns

- TAFE Directors Australia and the Australian Council for Private

Education and Training have expressed concerns that the new regulatory requirements

will lead to students missing out on education. This may be because a student’s

chosen course or provider is not approved for loans under the scheme, or

because the student will not be able to afford the out-of-pocket fees above a

capped loan amount.

- Consumer law advocates believe that the transitional measures do

not go far enough to support students who have incurred a loan debt under the

VET FEE-HELP scheme due to inappropriate provider behaviour.

- The Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee encouraged

the Minister to take into account the various stakeholder concerns on the broad

use of legislative instruments in implementing the VET student loans scheme.

The Committee also recommended the government establish a VET Ombudsman to

better protect students from fraudulent provider behaviour.

Key issues

- It is unclear whether the additional regulatory requirements

under the new VET student loans scheme will be effective in ensuring

appropriate provider behaviour and lead to better student outcomes. Existing

regulatory powers under the VET FEE-HELP scheme seem to not have been used

adequately.

- The specific requirements for VET student loans may complicate

administration for providers who offer a variety of student loans both under

the existing HELP loan scheme and the new VET student loan scheme.

- The new VET student loans scheme does not address the issue that many

VET graduates have relatively lower incomes. This may mean that repayment could

take an extended period and the default rates may be high. Overall, this means

the cost to the taxpayer of the program may continue to be considerable.

Structure of the Bills Digest

Through 2015 and 2016, there have been extensive attempts

to reform the VET FEE-HELP program, ensure appropriate provider behaviour and

contain the cost to government. Many of the provisions in the current Bill are

based on settings in the existing VET FEE-HELP program. As a result, this Bills

Digest should be read in conjunction with the Bills

Digest[1]

for the Higher

Education Support Amendment (VET FEE-HELP Reform) Bill 2015.[2]

This Bills Digest will focus on the effectiveness of the

2015 and 2016 reforms in considering the introduction of a new student loan model

through this package of VET student loans Bills. The Digest uses VET FEE-HELP

as a starting point for comparison with the proposed new VET student loans

program.

Commencement

The VET Student Loans Bill 2016 and the VET

Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016 commence on 1 January 2017.

Sections 1 to 3 and Schedule 2 of the VET Student Loans

(Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2016 commence

on Royal Assent. Part 1 of Schedule 1 commences at the same time as the VET

Student Loans Bill 2016. Part 2 of Schedule 1 commences at the later of the

commencement of the VET Student Loans Bill 2016 or immediately after the

commencement of the Higher Education Support Legislation Amendment (2016

Measures No. 1) Bill 2016. It does not commence at all if both these Bills do

not commence.

Purpose of

the Bills

The VET Student Loans Bill 2016 (the Student Loans Bill)

establishes a new income-contingent loan scheme (VET student loans) for

eligible students undertaking specified vocational education and training (VET)

qualifications at approved providers.

The VET Student Loans (Consequential Amendments and

Transitional Provisions) Bill 2016 (the Consequential Amendments Bill) amends

existing legislation to grandfather the current VET FEE-HELP loan scheme,

transition existing VET FEE-HELP providers to the new scheme, and allow more

information sharing between existing government agencies in order to improve

administration of VET student loans.

The VET Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016 (the Charges

Bill) sets out a charge to be levied on approved VET providers as a tax.

Structure

of the Bill

The Student Loans Bill is made up of 10 Parts:

- Part

1 sets out preliminary matters, such as commencement, objects of the Bill,

and definitions

- Part

2 details the circumstances in which the Secretary of the Department of

Education and Training may approve an application for a VET student loan

- Part

3 specifies the conditions under which VET student loans must be paid and

repaid

- Part

4 specifies how a VET provider may become approved to offer VET student

loans to its students

- Part

5 specifies other requirements which are to be placed on providers approved

to offer VET student loans

- Part

6 specifies how FEE-HELP balances under the VET student loans scheme are to

be re-credited

- Part

7 specifies what decisions under the VET student loans scheme are to be

considered reviewable decisions and how any review can be undertaken

- Part

8 specifies the regulatory powers granted to agencies to monitor the VET

student loans scheme

- Part

9 specifies the ways in which information disclosure under the VET student

loans scheme can be authorised and what offences apply when this power is

misused and

- Part

10 specifies general administrative provisions.

The Consequential Amendments Bill is divided into two

Schedules.

Schedule 1 of the Consequential Amendments Bill

deals with the substantive changes to relevant education legislation and is set

out in two parts:

Schedule 2 of the Consequential Amendments Bill

details transitional provisions to allow existing VET FEE-HELP providers to

become authorised as approved course providers under the new VET student loans

scheme.

The Charges Bill has one Schedule which provides a

framework for the imposition of a charge on approved providers. Details of the

charge will be set out in regulations.

Background

The regulation of the VET sector in Australia and the

administration of the VET FEE-HELP scheme have been subject to much

parliamentary and public debate and activity over the past decade. This Bills

Digest provides key background information and an update on developments since

the most recent reforms passed the Parliament in November 2015.[3]

A complicated

policy landscape

Emerging out of each state and territory’s separate trades

and training regimes, the current VET sector is governed by a myriad of

legislative frameworks, regulatory agencies and funding streams across

different levels of government and different jurisdictions.[4]

This complicated and fragmented policy landscape makes it challenging to

address systemic issues with VET such as improving provider quality and student

attainment. These structural barriers should be kept in mind when considering

the effectiveness of policy reforms such as VET student loans.

The

legislative framework

At a federal level, the legislative framework for VET

consists of three key pieces of legislation:

Each Act creates separate application processes, often

administered by separate Australian Government agencies and under different

legislative requirements, in order to be granted status as a registered

training organisation (RTO), approved to offer a HELP loan, or appear on the

Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students

(CRICOS).[5]

The

regulatory space

VET regulation is complicated, due to the federal system

of powers and responsibilities inherent in the Australian Constitution.

Education is not explicitly listed as one of the areas on which the Federal

Parliament has power to legislate under section 51 of the Constitution.[6]

Accordingly, education has been regulated primarily by the states and

territories.

New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania

have referred power to the Commonwealth to enable it to enact national

legislation dealing with VET matters.[7]

Victoria and Western Australia chose not to refer their authority for VET

matters to the Australian Government as part of the establishment of ASQA in

2011. Instead, they kept their own separate regulators. As a result, ASQA

undertakes the following activities:

- the

regulation of RTOs in all states and territories save Western Australian and

Victoria, except where RTOs based in these jurisdictions offer training to overseas

students or students in ASQA’s referred jurisdictions, the Australian Capital

Territory or the Northern Territory[8]

- the

regulation of English-language courses for overseas students except where the

provider is a school or a higher education provider and

- the

regulation of accredited VET courses.[9]

ASQA indicates on its website that it confers with the

state-based regulators in Victoria and Western Australia, and formal mechanisms

such as memorandums of understanding and communication protocols exist to support

a collaborative regulatory environment.[10]

Program and

funding flows

Multiple VET programs exist across Australia, with

multiple funding flows. This is in comparison to the relatively unified system

of higher education funding under the Higher Education Support Act 2003.

Based on the recipient and the mode of funding, VET

programs can be categorised in three ways:

- funding

to subsidise VET training at given providers. This is delivered either:

- through

intergovernmental agreements to states and territories (and so comes indirectly

from the Australian government) or

- directly

through state and territory programs

- funding

to offset any remaining fees for VET students. This is delivered either:

- through

student loans such as VET FEE-HELP and the new VET student loans program or

- through

fee waivers in line with state and territory program criteria

- funding

to achieve particular targeted VET outcomes. This may include support for

underrepresented student groups, or limited measures to improve provider

quality or student attainment. This is delivered either:

- through

intergovernmental agreements to states and territories (and so comes indirectly

from the Australian government)

- through

Australian government programs or

- through

state and territory programs.

Intergovernmental

agreements

At a federal level, the majority of funding is delivered

not through legislation, but through intergovernmental agreements. These are

designed to assist states and territories with the costs of running their own

VET programs, in line with certain agreed principles or reform objectives.

The Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial

Relations (IGAFFR) is the current overarching framework for Commonwealth-state

relations, agreed by all states, territories and the Commonwealth in 2008.[11]

Under the IGAFFR, a series of six National Agreements define the objectives,

outcomes, outputs and performance indicators, and clarify the roles and

responsibilities that guide the Commonwealth and the states in the delivery of

services in key sectors.[12]

National Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs) are the funding mechanism through

which the Commonwealth supports State and Territory efforts in delivering

services in key sectors.[13]

The current national agreement for the VET sector is the National

Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development (NASWD).[14]

The Australian Government provides states and territories with a given SPP

amount on an annual basis in accordance with this agreement.

To achieve certain specific time-limited reforms, the

Australian Government may enter into a given National Partnership with

jurisdictions. A National Partnership typically includes implementation funding

(to undertake the given reforms) and reward funding (to reward jurisdictions

when they reach agreed performance indicators).

The National Partnership on Skills Reform (NPSR) is the

current National Partnership for the VET sector, and required jurisdictions to

implement a number of reforms in order to be eligible for federal VET FEE-HELP

loans.[15]

It is due to expire on 30 June 2017, and has recently been reviewed.[16]

No agreement on future National Partnership funding after this date has yet

been reached, although the SPP will continue.[17]

Australian

government programs

A number of programs are also delivered by the Australian

Government. These include programs designed to increase the uptake of training

within industry (the Industry Skills Fund), incentives to reduce the barriers

faced by employers and apprentices in the apprenticeship system (the Australian

Apprenticeships Incentives Program and the Trade Support Loans scheme),

measures to increase the access to training (the Adult Migrant English Program

and the Skills for Education and Employment scheme), and research and

administrative support for the national training sector (funding for the

National Centre for Vocational Education and Training and the Australian

Industry and Skills Committee).

These programs are typically administered by the

Department of Education and Training through funding agreements, out of

ordinary budget appropriations.[18]

Specific RTOs are chosen to receive funding through competitive or

non-competitive application processes.[19]

Particular eligibility criteria is associated with support provided for

apprentices.[20]

State and

territory government programs

States and territories typically fund the training system

through block funding or competitive funding processes, with funding allocated

between public providers like TAFEs, community and not-for-profit providers,

and private providers. As a result providers are able to offer a certain number

of training places. Often the number of overall training places is capped,

which maintains some level of government discretion over budget outlays.

States and territories will fund these subsidised places

in line with their own locally determined skills needs – for example, a

qualification in defence engineering may be subsidised in one jurisdiction but

not another. The level of subsidises is often used to make a particular

vocation more attractive or to support a particular group of disadvantaged

students through greater subsidises or fee waivers.[21]

As the criteria for these subsidises are determined by state and territory

governments, they are typically managed through funding contracts with

particular RTOs. The ability of state bureaucracies to manage these contracts

in an effective way has been criticised as states and territories have sought

to expand their VET sectors in recent years.[22]

Outside these subsidised places, students are still able to undertake

unsubsidised (full fee) training from RTOs.

Policy

design and responsibility

As can be seen from the discussion above, the landscape

for VET is complex. While a national regulator, ASQA, exists, its jurisdiction

does not yet cover all RTOs. Even with regards to the RTOs who fall under its

jurisdiction, these RTOs may be receiving funding through VET FEE-HELP and

other Department of Education and Training programs, through state and

territory programs administered by state and territory bureaucracies, or

through up-front student fees. Different frameworks apply to this funding, from

legislative requirements for student loans, to contractual obligations set out

in funding agreements, and aims and objectives in intergovernmental agreements.

The application of consumer law in safeguarding students who are unaware of

their rights in purchasing training adds another layer of complication.

How these different legal requirements and contractual

frameworks interact may be unclear to the provider, to the student, and to the

policy officer or program manager. Their complexity would also make it

challenging to identify which policy reforms or funding streams lead to

particular practices in the VET sector, and increase the possibility for

unintended consequences resulting from policy changes.

Understanding the context and choices of participants in

the VET sector is also difficult due to a lack of comprehensive data. A single

student identifier was only introduced from 1 January 2015.[23]

Previously, due to the separate state and territory based VET systems, a

student could not be tracked across different jurisdictions, reducing the

capacity of policy makers to examine whether students who abandoned

qualifications or dropped out may have finished their qualifications across

jurisdictional boundaries.

The data collection for VET is also problematic. While

states, territories and the Australian Government jointly fund the National

Centre for Vocational Educational Research (NCVER), until 2014 its data

collection only reported on funding that was government subsidised. Reporting

on the broader VET sector, called total VET activity, has been implemented

progressively since 2014, although there are still exemptions from this

reporting.[24]

The total VET activity collection does not currently identify the entire VET

FEE-HELP cohort, which also makes analysis of student outcomes and funding

effectiveness difficult.[25]

Finally, the lack of clarity over who is responsible for

the VET sector, how it operates, what it involves, and why it works (or

doesn’t) can also be seen in the policy ambitions for VET in Australia. While

there is no formal statement on what the VET sector is or should be, the

parties to the NASWD have agreed that their reforms should aim to create:

1. A national training system, accessible to all working age Australians,

that provides them with the opportunity to develop the skills and

qualifications needed to participate effectively in the labour market.

2. A responsive, agile and equitable national training system that meets

the needs of industry and students (including those from disadvantaged groups

or locations) and provides pathways into, and removes barriers between,

schools, adult, vocational and higher education, and employment.

3. A high quality national training system that is centred on quality

teaching and learning outcomes.

4. A national training system where individuals, businesses and

jurisdictions have access to transparent information about training products,

services and outcomes so they are able to make informed choices and decisions.

5. A sustainable national training system with a stable funding base that

promotes opportunities for shared investment across governments, enterprises

and individuals.

6. An efficient national training system, where government efforts

appropriately respond to areas of future jobs growth and support the skills

needs of Australian industry.

7. A national training system that works with Australian businesses and

industries to develop, harness and use the skills and abilities of the

workforce.[26]

The first aspiration suggests that workforce participation

is the key – the emphasis may be on skilling Australians to participate in

existing industries. But the sixth and seventh aspirations indicate it may be

about future jobs, growth industries and innovation. At the same time the

second aspiration indicates the VET system is also responsible to provide

pathways back into learning and employment for students who might be

disengaged. A focus on equity (such as using VET as a pathway to disadvantaged

students) may result in lower attainment rates, depending on how this cohort is

supported. A focus on existing industry needs may raise calls for retraining

and industry transition when economic restructuring occurs. A focus on future

jobs growth may result in governments picking winners and be ineffective.

Understanding how administrative (funding, legislation,

programs) and policy (design, aims, responsibility, outcomes) complexity is

inherent to the VET sector is crucial in considering how schemes like VET

FEE-HELP or the new VET student loans scheme may work.

The VET

FEE-HELP Scheme

Development

VET FEE-HELP was introduced in June 2007 by the Howard

Government, as part of legislative amendments to Higher Education Support

Act 2003 (HESA).[27]

At the time, it extended the existing loan scheme for full-fee paying higher

education students (FEE-HELP) to those vocational education and training (VET)

students undertaking full-fee paying Diploma, Advanced Diploma, Graduate Diploma

and Graduate Certificate qualifications. The program commenced on 1 January

2008, and while HESA set out the broad framework, the capacity for the

department to manage VET FEE-HELP was set out further in VET Guidelines.

The focus on full-fee paying students was in line with the

existing FEE-HELP scheme; this was supposed to offer financial support to those

students who would not otherwise receive subsidises to undertake a VET

qualification, thereby expanding the pool of students who could access VET.

In addition, the introduction of VET FEE-HELP was

regulated by the use of credit transfer arrangements. These required the VET

provider to have a credit transfer arrangement in place with a higher education

provider (for example, a university). This meant that the higher education

provider had assessed the training offered by the VET provider and was willing

to accept the VET qualification as credit towards a higher education

qualification. While it did not mean there was an entirely independent audit of

the VET provider, the higher education provider had a reputational reason to

ensure that it only recognised qualifications and students who were capable of

meeting its own particular standards and qualifying for one of its own courses.

Reforms to

expand the VET system

There were a number of significant reforms to VET under

the Rudd and Gillard governments which had the effect of expanding the VET

system. Amendments in 2008 ensure students in Graduate Certificate and Graduate

Diploma qualifications could access VET FEE-HELP, but maintained the credit

transfer requirements.[28]

Following moves by the Victorian Government to introduce

contestable VET funding from 2009, the Australian Government allowed VET

FEE-HELP loans to be offered to any student (including subsidised students) and

any RTO (whether they had a credit transfer arrangement or not).[29]

These restrictions were only removed for any state deemed to be a ‘Reform

State’.[30]

At the time, only Victoria was listed, but the other jurisdictions had been encouraged

to similarly reform their VET sectors and open funding up to a variety of

providers.

Significant reform emerged out of the 2010–11 Budget, on

11 May 2010, with the announcement of a national entitlement to a training

place, expanding access to VET FEE-HELP to further VET qualifications,

transparent information for students, and a new national VET regulator.[31]

The creation of the NPSR in 2012 was intended to progress these VET reforms.[32]

This went hand-in-hand with the expansion of VET FEE-HELP: as each jurisdiction

implemented the agreed reforms of the NPSR, they each became ‘Reform States’,

allowing students to enrol as they wished and directing funding in the form of

state or territory subsidises, as well as VET FEE-HELP loans, in line with student

preferences.

As the new national VET regulator, ASQA was given

responsibility for regulating registered training organisations over which it

had jurisdiction. This involved assessing a provider’s capacity against the

relevant Standards, both for those organisations applying to be registered and

become an RTO, and existing RTOs.[33]

Once a provider was registered with ASQA, it could then apply separately to the

Department of Education and Training in its various incarnations to be approved

to offer VET FEE-HELP loans to its students. The VET FEE-HELP process was

governed by a separate set of guidelines under HESA.

Emerging

issues with VET FEE-HELP

The first concerns were flagged by a review undertaken by

the Victorian Government in 2010, indicating that some VET students were

unwilling to take out VET FEE-HELP loans ‘because they were afraid of debt’.[34]

Concerns about student debt are common to the HELP suite of loans more

generally: the debt profile associated with the HELP suite of loans was most

recently analysed in 2014 by the Grattan Institute.[35]

Section 3.5 of the report dealt specifically with VET FEE-HELP and found that

people with a vocational education diploma or advanced diploma were 50 per cent

less likely to repay their loan than those in higher education.[36]

Any default on existing student loans would be a potential cost to the budget,

as the budget papers provide for a fair value of HELP loan debt, considering it

an asset as it is likely to be repaid.[37]

The expansion of VET FEE-HELP loans was also reported as

having changed the business model of the VET sector. As the loan involved an

upfront payment to a provider, new providers had incentive to enter the market

and utilise methods to build up their student numbers quickly. Private

providers often were largely dependent on government funding from VET FEE-HELP

loans.[38]

There were no penalties in place should a student fail to complete a

qualification, nor would the provider have to pay back the loan amount. In

order to entice more students – and get more funding, VET FEE-HELP providers

started to utilise aggressive marketing techniques, including brokers, agents,

inducements and potentially misleading advertising practices to direct students

to their particular course offerings.[39]

The Opposition first raised VET FEE-HELP quality concerns

in response to media reports in October 2014.[40]

The Department of Education’s capacity to properly administer and scrutinise

the scheme was questioned by the Australian Greens’ spokesperson in the same

month.[41]

Media reports of registered training organisations using inducements such as

iPads or laptops to sign up students who were not academically suited to

undertake qualifications continued.[42]

Government

responses and further scrutiny

Government reforms to address identified issues with VET

FEE-HELP and the broader VET sector ensued through late 2014 and 2015.

First, the relevant Standards for registered training

organisations were updated, following a process of consultation and agreement

from relevant Council of Australian Government (COAG) ministers.[43]

These became effective as of 1 January 2015, with ASQA provided with additional

funding of $68 million over four years to enforce them.[44]

The new Standards would apply to all RTOs, regardless of whether they offered

VET FEE-HELP and would have a sector-wide impact.

Second, to address particular issues with VET FEE-HELP,

the relevant guidelines were revised in March 2015, to ban RTOs from providing

inducements such as laptops, iPads, vouchers or cash.[45]

Third, the VET Guidelines were revised again in June 2015,

with elements becoming effective in July 2015 and January 2016.[46]

These measures were intended to ensure VET FEE-HELP providers gave accurate

information to students about the nature of VET FEE-HELP loans, marketed VET

FEE-HELP assistance responsibly, were held accountable for the agents they had

contracted to sign-up students, did not create any barriers to withdrawal for

students (to ensure they couldn’t delay withdrawal and so ‘skim’ the VET

FEE-HELP funding off an enrolment), and to prevent a VET FEE-HELP provider

charging more than 25 per cent of the fee in any one fee-period.

While these reforms were being implemented, Parliamentary

scrutiny of the VET sector emerged as a result of a Senate inquiry. The Senate

Education and Employment References Committee established an inquiry into ‘the

operation, regulation and funding of private vocational education and training

(VET) providers in Australia’ on 24 November 2014. The Terms of Reference

included an examination of the ‘operation of VET FEE-HELP.’[47]

The final report was tabled on 15 October 2015.[48]

Key issues identified by the Senate report included:

- the

approach of ASQA—its risk-based regulatory approach means that it focuses on

the provider, rather than assessing the qualifications provided to the student.

The Committee view was that ‘there was every reason to doubt ASQA is fit for

purpose’[49]

- the

capacity of the Department of Education and Training, as well as ASQA, to

monitor VET FEE-HELP arrangements

- the

use of brokers by RTOs and their clear financial interest in signing up

students to courses regardless of the student’s need or proficiency

- the

ability of RTOs to subcontract out their training to unregistered

organisations, lowering the level of scrutiny and

- the

lack of clarity regarding review or assistance for domestic students who have

issues with VET FEE-HELP debts, as a separate Ombudsman for overseas students

already exists.[50]

Further legislative reform to the VET FEE-HELP scheme was

introduced in October 2015.[51]

The Higher Education Support Amendment (VET FEE-HELP Reform) Bill 2015 enhanced

the regulatory powers under HESA to include the following additional

requirements for providers:

- a

minimum period for operating as a registered training organisation

- a

minimum period for providing courses leading to award of qualifications in the

Australian Qualifications Framework

- a

‘student entry procedure’, including minimum academic standards, for VET

FEE-HELP students

- ensuring

the consent of a responsible adult is provided in case of students under the

age of 18 applying for VET FEE-HELP loans and

- creating

a two-day ‘cool off’ period to ensure that prospective students have time to

reflect on their VET enrolment before they seek a VET FEE-HELP loan.

Investigatory and monitoring powers were introduced,

including a civil penalty framework for cases of non-compliance, to ensure the

new requirements on VET FEE-HELP providers were adhered to. New administrative

powers were created to allow the Secretary of the Department to re-credit a

student’s FEE-HELP balance in certain circumstances, essentially cancelling

their VET FEE-HELP loan. This would assist where providers had not adhered with

their new obligations and so enticed students into taking out a loan without

proper information or authorisation.

Following the introduction of this Bill to Parliament,

significant amendments were introduced in the Senate and the Bill passed both

Houses on 3 December 2015, to commence on 1 January 2016.[52]

These amendments had the effect of:

- freezing

total 2016 VET FEE-HELP loan amounts for existing VET providers at 2015 levels,

with the Secretary granted the power to make exemptions for monopoly providers

in an identified area of national importance where the course was relevant to

employment in a licensed occupation

- introducing

new entry requirements for registered training providers seeking to offer VET

FEE-HELP loans

- moving

from payments in advance to payments in arrears for the largest training

providers and setting new reporting requirements

- allowing

the government to pause payments to providers with poor performance pending

resolution of performance issues and

- making

other minor amendments to:

- expand

the appointment of investigators to external non-government bodies to better

cope with expertise and resourcing requirements and

- allow

fee charging associated with attesting to the veracity of a provider’s literacy

and numeracy testing tool.[53]

A new version of the VET Guidelines was issued, utilising

the new legislative powers granted by the amendments to HESA and

specifying in more detail the new requirements placed on VET FEE-HELP

providers.[54]

In contrast, the Opposition had set out a series of

amendments to the VET FEE-HELP Reform Bill which would have gone further than

those passed by the Parliament. They included:

- the

creation of an industry funded national VET Ombudsman

- seeking

the Auditor-General to conduct an audit on the VET FEE-HELP scheme and

- requiring

the Department to write to prospective VET FEE-HELP students to inform them of

their potential debt and seek consent for the loan, rather than relying on

providers to do so.[55]

The press release on the Opposition’s proposed amendments also

flagged that in referring the VET FEE-HELP Reform Bill to a Senate Committee

for consideration, the Australian Labor Party would utilise this committee

inquiry to examine options for capping tuition fee levels for courses covered

by VET FEE-HELP loans and to lower the lifetime limit on VET FEE-HELP student

loans.[56]

The Greens then Tertiary Education Spokesperson, Senator Robert Simms, called

upon the Government to ‘fix’ the for-profit VET system, ultimately by

disallowing for-profit providers from offering VET FEE-HELP.[57]

These iterative changes through 2015 and 2016 essentially

increased the requirements on RTOs in relation to VET FEE-HELP students only.

It had the unintended effect of increasing the administrative complexity for

providers, as many VET FEE-HELP providers would also be training students who

were not receiving VET FEE-HELP assistance and therefore be covered by

different entry requirements and applications processes.[58]

A new model

for VET FEE-HELP

The changes introduced through 2015 were essentially stop

gap measures, with the Government announcing it would undertake a ‘full

overhaul of VET FEE-HELP’ in time for 2017.[59]

On 4 April 2016, Senator Scott Ryan, the then Minister for

Vocational Education and Skills announced that consultations on the future of

VET FEE-HELP had commenced.[60]

The consultations were informed a discussion paper on the VET FEE-HELP redesign,

which was released on 27 April 2016.[61]

Submissions were open until 30 June 2016. The discussion paper did not

include formal terms of reference, but the Minister’s foreword stated:

We need to ensure the scheme is underpinned by a strong

regulatory framework that provides greater protection for students, delivers

quality and affordable training that has strong links to industry needs, at an

affordable cost to taxpayers. This is not simply a matter of private versus

public sector provision, VET has always been a blended sector and should remain

so. To achieve this, there needs to be a frank assessment of the scheme thus

far. To address the problems we must first understand them. We must also

specifically consider the impacts of possible changes to the scheme, in

particular the incentives they provide for providers and students and, in some

cases, governments. That is why I am committed to a wide ranging and

comprehensive consultation process.[62]

The discussion paper summarised the inception and

development of the VET FEE-HELP scheme, including its expansion and detailed a

series of what it termed design flaws, including the lack of appropriate

regulatory powers. It examined key trends in student numbers, the significant

increase in program expenditure and provided some analysis of the costs

involved for VET FEE-HELP funded qualifications as compared to non-VET FEE-HELP

funded qualifications. It also attempted to quantify how successful the 2015

and 2016 reforms had been and outlined options for change which would protect

students, regulate providers appropriately, and ensure better VET system

management.

As part of its options for change, the discussion paper

sought feedback on a series of discussion questions.[63]

Topics covered included whether further student eligibility requirements were

necessary, the possibility of introducing lifetime loan limits (to protect

students from becoming too indebted over the course of their vocational

education and training), whether the government should introduce limits on the

amount which could be loaned per course, what ways existed to ensure students’

interests were paramount, including better information and regulation, what

data could be used to measure the quality of providers and courses, and

eligibility requirements for providers and courses under any new scheme.[64]

In the lead up to the 2016 federal election, the future of

VET FEE-HELP emerged as a point of difference between the major political

parties. In May 2016, the Leader of the Opposition promised to cap VET FEE-HELP

loan amounts at $8,000 a year as part of the ALP’s reply to the 2016–17 Budget.[65]

Further reforms to VET FEE-HELP included a change to the funding incentives to

ensure greater completion rates, better links between loans and the needs of

industry, cracking down on the use of third-party agents by VET FEE-HELP

providers, raising the entry requirements for providers and ensuring regulators

had tougher powers to audit, investigate and suspend unscrupulous providers.[66]

This reform package for VET FEE-HELP subsequently became an ALP election

commitment.[67]

The Australian Greens went further than the Opposition in

proposing that for-profit VET providers be ineligible for government funding,

including loans such as VET FEE-HELP.[68]

Conversely the Coalition criticised aspects of these

proposals, especially the ALP’s promise to cap VET FEE-HELP loans.[69]

The then Minister drew attention to the negative reaction of peak bodies in the

sector to the prospect of caps, and likely consequences for students in

additional out of pocket costs in cases where a capped loan was not enough to

cover the course fee.[70]

The Coalition election policy was to ‘redesign the VET FEE-HELP scheme for

2017’.[71]

Committee

consideration

Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee

The Bill was referred to the Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 7 November 2016. Details

of the inquiry are available on the Committee’s website.[72]

The concerns raised by the submissions and participants in

this inquiry will be explored in more detail in the ‘Position of major interest

groups’ and the ‘Key issues and provisions’ sections of this Bills Digest.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had

no comment on the Consequential Amendments Bill, but has sought further

information from the Minister on certain aspects of the Student Loans Bill and

the Charges Bill that it regards as problematic.[73]

In regards to the Student Loans Bill, the Minister’s advice

has been sought on the following provisions:

- clause

65, which imposes personal liability on executive officers of approved

course providers under certain circumstances without explanation as to whether

the processes set out in the Guide

to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement Powers[74]

in relation to the incorporation of vicarious liability offences into statutes

has been followed

- clause

74, which limits the decisions for which an internal review or appeals

process is applicable, thereby limiting the capacity of applicants under the

VET loans scheme to seek to overturn potentially unfair decision making

- clauses

77 and 81, which grant broad administrative powers for decision-makers

under the VET student loans scheme to reconsider their decisions once made, which

could be considered to make administrative decisions more unpredictable and

less certain if they can be revisited at any time

- clause

85, which allows for infringement notices to be issued in the case of an

offence or civil penalty provision under the proposed Act, also without

explanation as to whether the processes in the Guide

to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement Powers[75]

have been followed

- subclause

101(2), which imposes absolute liability in relation to one element of the offence

of unauthorised access to, or modification of, personal information of loan

recipients, again without detailed justification or discussion of whether the

approach accords with the Guide

to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement Powers[76]

- clause

114, which allows the Secretary to delegate, in writing, all of his or her

powers under the proposed Act to an APS employee without regard to whether all

these powers are appropriate for delegation and whether there is a level of

seniority or experience required to utilise them and

- subclause

116(5), which allows the rules made under the proposed Act to adopt or

incorporate matters set out in another written instrument. This may impact on parliamentary

scrutiny as the document referred to may be subject to change without the

parliament being advised.[77]

The Committee also sought the Minister’s advice on an

aspect of the Charges Bill:

- clause

7, which allows for the amount of the charge to be set by regulation

without any guidance on how it should be set or any limit to the amount.[78]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Following media reports on the scope of the new VET

student loans scheme, the Labor Opposition Shadow Minister for TAFE and

Vocational Education put out a series of press releases noting where the new

scheme incorporated elements of the ALP’s election policy.[79]

The ALP also introduced amendments to the Student Loans

Bill in the House of Representatives. These amendments would have the effect of

establishing an ombudsman to assist students with complaints regarding the VET

student loans scheme, and to require the ombudsman to publish information about

the number of complaints received on a six monthly basis.[80]

The proposed amendments were not passed in the House of Representatives.[81]

Despite this, the Australian Greens stated that they had

reached agreement with the Government to introduce an ombudsman to the VET

student loans scheme.[82]

The Government has also stated it will establish an ombudsman, but these

provisions were not in the Bills as introduced.[83]

The sole crossbencher who spoke on the Bills in the House

of Representatives, Rebekha Sharkie of the Nick Xenophon Team, supported the

reforms, but expressed concern regarding the adequacy of student protections,

the appropriateness of the eligibility requirements for funding specific

courses, and the capacity of the Department of Education and Training to

administer the new scheme properly in the light of its administrative history.[84]

Position of

major interest groups

The major interest groups all express a view that while

reforms to the VET FEE-HELP program are needed, the proposed VET student loans

scheme contains provisions that are too arbitrary and will restrict access and

equity for students enrolling in vocational education and training. This

section provides an overview of these criticisms: stakeholder concerns

regarding particular provisions are addressed in the ‘Key issues and provisions’

section of the Bills Digest.

The peak body for the private VET sector, the Australian

Council for Private Education and Training (ACPET) supports key elements of the

Bill, but states that ‘there are a number of features of VSL [VET student

loans] that will not support quality training choices and outcomes for some

students’ and that ‘the reforms will see a major downgrading of the

Commonwealth Government’s commitment to vocational education and training, with

significant implications for the future of Australia’s workforce development’,

with an estimated 500,000 students ineligible for support under the new program

and so missing out on vocational education and training and the resulting job

opportunities.[85]

ACPET also contends the reforms will lead to major job losses across the

sector, as some providers will miss out on funding and have to close.[86]

The peak body for the public TAFE sector and the VET

divisions of dual sector universities, TAFE Directors Australia (TDA),

expresses similar concerns regarding student access. TDA contends that as access

was the principal reason for establishing VET FEE-HELP in 2008 and then

expanding the scheme through 2012, limiting access to only certain students

undertaking certain courses in certain providers as has been proposed under the

new scheme would conflict with the stated aims of the current National

Partnership on Skills Reform.[87]

The major unions who have made submissions to the Senate

inquiry into the Bill include the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU),

the Australian Education Union (AEU), and the National Tertiary Education

Union. The ACTU comments that the Bills represent a good first step, although

the extensive use of delegated legislation to define elements of the new loans

scheme and the short time span before the new scheme starts in 2017 make it

hard to assess the potential effectiveness.[88]

The ACTU calls for further reforms, involving a 30 per cent cap on funding

allocated contestably, restoring the TAFE system as the public provider of

quality across the country, conducting a review into the future of the

market-driven approach to VET, and ensuring the VET regulator has the necessary

powers and resources to audit both provider quality and student training

outcomes.[89]

The AEU endorses the ACTU submission in full.[90]

The NTEU gives qualified support for the measures in the Bills, but expresses

concerns that the reforms will entrench the different funding and regulatory

regimes between higher education and VET and so generally lead to gaps in the

provision of tertiary education for students who might be in need of

alternative entry pathways and other forms of education.[91]

Industry bodies the Australian Industry Group and the

Business Council of Australia urge the Senate to pass the Bills, noting there

may be some unintended consequences of the new scheme due to its design.[92]

Key recommendations are for the government to allow grandfathered students to

continue to access a VET FEE-HELP loan through 2018, to change the legislation

so that the concept of eligible courses better connects with industry need and

to require government to consult with industry in developing rules for the new

scheme, to remove the capacity for ASQA to conduct audits of the scheme, and to

require the government to publish VET market information and real-time data on

government expenditure to better inform public assessment of the VET student

loans scheme.[93]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Student Loans Bill notes

that the new VET student loans scheme is expected to reduce the value of new student

loans being issued by more than $2.4 billion per annum by the end of the

forward estimates in 2019–20, leading to an estimated reduction in otherwise

total HELP debt of more than $7 billion by June 2020 and by more than $25

billion by June 2026.[94]

The proposed reforms will have a negative impact of $58.6

million on underlying cash over the forward estimates, including administered

and departmental funding.[95]

Special

appropriations

There are no special appropriations associated with these

Bills.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that while the Bills engage with the right to privacy and

the right to be presumed innocent, what limitations exist under the Bills are

reasonable, necessary and proportionate.[96]

Overall the Bills are compatible with human rights.[97]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considers

that the Bills do not give rise to human rights concerns.[98]

Key issues

and provisions

Overview

Broadly, five key issues have emerged in the commentary

and policy history surrounding VET FEE-HELP and new VET student loans which

have only been partly addressed by the current Bills and accompanying material:

- the

unclear purpose of VET

- the

design of the VET market

- the

effectiveness of providers

- the

costs of education and

- the

regulatory environment.

The unclear

purpose of VET

As noted earlier in this Bills Digest, there is a lack of

clarity over the purpose of VET. The Student Loans Bill goes some way to resolving

this, by indicating in the Objects of the Bill (clause 4):

The object of this Act is to provide for loans to students

for vocational education and training, ensuring that loans are provided:

(a) to genuine students; and

(b) for education and training that

meets workplace needs and improves employment outcomes.

This is a narrower definition than that offered by the

intergovernmental agreements associated with VET, which do not indicate some

students may not be ‘genuine’ or that the key purpose of VET is workplace

related and leads to employment. Indeed, under the intergovernmental

agreements, the purpose of VET as a way of removing barriers for students who

otherwise might be excluded from education, training and employment is

specifically stated.[99]

The Student Loan Bill attempts to resolve these issues

through the concepts of eligible students, approved courses and approved course

providers.

Eligible

students

The Secretary can only approve a VET student loan if they

are satisfied the applicant is an eligible student (clause 7

in Part 2 of the Student Loans Bill). The Student Loans Bill also

provides for a definition of an eligible student (clauses 9 through 12).

These provisions ensure the student is enrolled in the course, has provided the

required documentation, is undertaking the course primarily at a campus in

Australia and is either an Australian citizen, holder of a permanent

humanitarian visa who is usually resident in Australia, or a qualifying New Zealand

citizen. These are fairly standard provisions and similar requirements can be

found in the Higher Education Support Act 2003 in relation to the HELP

series of student loans.[100]

Clause 12 of the Bill creates a duty on providers to

assess students’ academic suitability for their course. This echoes the

‘student entry procedure’ required by the VET FEE-HELP Reform Bill in 2015.[101]

However that element of the VET FEE-HELP reforms was only introduced from 1 January 2016,

so it is unclear as to how effective it has been, or whether implementation has

been challenging. It also raises the question as to whether this is an

appropriate requirement, considering the overall purpose of VET has been stated

as removing barriers to entry, rather than creating new ones.

There is also some evidence about the nature of the VET

FEE-HELP cohort to date. A study undertaken by the National Centre for

Vocational Educational Research (NCVER) in 2015 found that in comparison with

non-VET FEE-HELP assisted students, those assisted by VET FEE-HELP were more

likely to:

- be

female

- be

aged under 25 years than over 35 years

- have

a disability

- not

be employed and

- be

attending externally.[102]

The 2015 and 2016 reforms to VET FEE-HELP were based on the

assumption that those students were systemically being enticed into taking

education which was academically inappropriate for them. As was discussed

earlier, there was also significant anecdotal reporting of VET FEE-HELP students

being unaware they had entered into a loan. NCVER showed that the VET FEE-HELP

student cohort is different to other VET students. It may be that in expanding

access to VET FEE-HELP, the program was being utilised by a cohort that had been

previously underserviced by HELP student loans.

In higher education, specific funding is available to

providers to support disadvantaged students who have additional support needs,

such as academic assistance.[103]

This includes targeted funding to support students with disability.[104]

No similar Australian Government program exists for VET students, even though

based on the NCVER study, students with disability are more likely to utilise

VET FEE-HELP compared with the broader VET cohort.

Continuing to require some form of student academic

assessment may actually discourage those students who could best benefit from

financial assistance to undertake VET qualifications, while not addressing the

issue of whether providers are funded adequately to support these students

throughout their studies.

Approved

courses

As per existing requirements for VET FEE-HELP, only diploma

and higher level VET courses are eligible for VET student loans.[105]

However, there are two new provisions in relation to approved courses which

both significantly narrow the scope of VET student loans and alter the

relationship between government and VET providers.

Under the existing VET FEE-HELP scheme, as in higher

education and VET sectors generally, providers have the ability to use third

parties to assist in course delivery, either through sub-contracting or other

arrangements. At best this can allow for greater collaboration or innovation in

the provision of training, with RTOs able to contract out the delivery of

particular units or functions such as student administration to specialists in

these fields. At worst it can lead to substandard or inappropriate practices

and lower costs for the provider but not the student.

Clause 15 of the Student Loans Bill creates

additional barriers for these types of contractual arrangements: providers

approved to offer VET approved courses will only be able to be delivered by

another provider approved under the VET student loan scheme, a person or body accredited

by the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency (TEQSA, the national regulator

for higher education), or a person or body approved in writing by the

Secretary. The Explanatory Memorandum notes that this will address concerns

that some VET FEE-HELP providers have been essentially selling access to the

scheme, rather than delivering training.[106]

However, these new barriers could dissuade providers from working with other

entities to develop innovative approaches to training that may serve particular

needs such as students studying via distance or online methods, or students

with special needs.

The relationship between providers and government is also

significantly altered by the authorisation of a new legislative instrument

under clause 16 of the Student Loans Bill, the courses and loan caps

determination. This allows the Minister to determine which courses of

study will be eligible for VET student loans and how much financial support

(given as a maximum loan amount) each course will be eligible for.

Currently tertiary education funding from the Australian

Government is entrusted to providers for their use. Regulatory agencies such as

TEQSA and ASQA and associated legislative standards create barriers to entry,

but once registered by a given regulator, each institution is responsible for

its funding in accordance with various guidelines. This can come in the form of

funding dedicated to a particular undergraduate or research place, or to assist

students with up-front costs through loans.[107]

The VET FEE-HELP scheme was also established on this basis, emerging as it did

out of the existing HELP series of loans. The courses and caps determination

marks a significant intrusion by government in the operations of RTOs. It will

change the funding incentives for vocational education and training and may

lead to examples where a certain course that was eligible for a VET FEE-HELP

loan is not eligible for a VET student loan. It shifts the funding model to one

more akin to that used by states and territories, which as has been discussed,

typically provide subsidises and set places in line with local skill needs.

The use of this new power is also arbitrary. While the

Explanatory Memorandum states that ‘it is anticipated the courses approved in

the determination will be limited to those courses with a high national

priority, that align with industry needs and lead to employment outcomes’, the

development of the courses and caps determination is not guided by any

provisions of the proposed Act.[108]

The Department of Education and Training has released a provisional list of

approved courses for consultation.[109]

This list includes the following criteria for approval:

Courses are approved if they are current (in other words, not

superseded), and on at least two state and territory subsidy/skills list, or

are science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) related or tied to

licencing, accreditation, or registration requirements for a particular

occupation.[110]

These criteria do not appear in the proposed Act and do not

have to be adhered to in developing the list of approved courses. This creates

uncertainty for providers whose eligibility can be changed at any moment, even

if they meet all other requirements of the proposed Act. Including specific

criteria or consultation processes in the proposed Act would go some way to

clarifying the purpose of the loans and providing greater surety to providers.

Approved

course providers

The Student Loans Bill creates extensive requirements for

those seeking to become an approved course provider, and so offer approved

courses to eligible students who can apply for VET student loans.

Part 4 sets out the conditions under which an RTO can

become an approved course provider. Many of these are holdovers from existing

provisions under VET FEE-HELP: it is interesting to consider how these will

operate. As with VET FEE-HELP, Part 4 of the proposed Act allows aspects of

these entry standards to be specified further in the rules. These include the

‘provider suitability requirements’ and how to determine whether those involved

in the operation of an RTO constitute a ‘fit and proper person’.

Clause 26 in Part 4 lays out the matters that

may be dealt with under the provider suitability requirements. Many of these

aspects, while building on typical assessment criteria under programs such as

VET FEE-HELP, potentially raise more questions than they answer. What standards

for ‘financial performance’ can be met when a company’s business model is

dependent on a government funded program such as VET student loans, a program

whose other eligibility criteria (such as the approved course list) can be

changed as needed and so lead to significant reductions in funding? How will

ensuring approved course providers have ‘experience in providing vocational

education’ allow new entrants to enter the market and drive competition and

innovation? How will ‘student outcomes’ be taken into consideration – will poor

student outcomes be seen of an example of low provider quality, or of a

provider seeking to offer training to student cohorts with poor literacy and

numeracy skills to start with? What constitutes an ‘industry link’?

These factors have the effect of narrowing the pool of

possible applicants – those with evidence of experience in vocational education

and training, good student outcomes and industry links are more likely to be

established RTOs, with developed curricula and training methods. Whereas

previously the VET FEE-HELP scheme could assist every student undertaking a

Diploma at an extensive range of providers, the new VET student loans scheme

limits the scope of assistance. Fewer providers are likely to be approved for VET

student loans: they will be able to receive funding for fewer courses and enrol

fewer students.

The design

of the VET market

The use of

listed providers

Clause 27 of the Student Loans Bill allows the rules

to stipulate that a listed course provider will be taken as

having met one or more of the course provider requirements. The Explanatory

Memorandum states:

For example, the Rules may specify that a TAFE established by

a State is taken to meet the ‘fit and proper person’ requirement, or similarly

the Rules may provide a listed course provider is not required to be a body corporate.[111]

Listed course providers are set out at subclause

27(2). They include Table A and B providers under HESA (the public

and not-for-profit universities), state and territory TAFE institutes, and any

other training organisation owned by the Commonwealth, a state or a territory.

This listing can also be augmented by the Rules as provided for under the

proposed Act. All listed course providers (including any specified in the Rules)

must be RTOs.

The Consequential Amendments Bill sets out

arrangements for moving to the new approved provider arrangements. Item 2

of Schedule 2 to the Consequential Amendments Bill provides that Table A

and B providers under HESA (the public and not-for-profit universities),

state and territory TAFE institutes, and any other training organisation owned

by the Commonwealth, a state or a territory are taken to be approved course

providers on 1 January 2017 if they are a VET provider immediately before that

date. This approval will be for seven years (item 5 of Schedule 2

to the Consequential Amendments Bill). Other bodies that are VET providers

immediately before 1 January 2017 which apply to the Secretary before 1 January

2017 and are taken to be suitable as an approved course provider during the

transition period will be taken to be approved by the Secretary for the

‘provider transition period’, which will expire on 30 June 2017 or a later date

determined by the Minister (items 1 and 8 of Schedule 2 to the

Consequential Amendments Bill). The proposed VET Student Loans scheme

automatically includes public providers in the transition period, putting

private providers at a disadvantage.

VET and

higher education

As a concept, listed providers are also found in HESA,

where ‘listed providers’ are well-established universities that have automatic

access to certain funding programs. This is not the only conceptual borrowing

from the higher education framework. Since the creation of the Higher Education

Contribution Scheme (HECS) in 1989, the major public universities have had

their undergraduate course fees capped at a set level. Since 1996, three

different cap amounts have been used, set in legislation, and associated with

particular qualifications. It is interesting to note that unlike higher

education, the proposed cap amounts for VET student loans are not set by the

Student Loans Bill, but will be entirely dependent on the courses and caps

determination.

At a federal level, higher education funding is structured

very differently to that of VET. HESA provides for a set government

subsidy for undergraduate students, and then caps the amount students can be

charged. Together this Commonwealth contribution and student contribution are

intended to make up the cost of providing education. In the more fragmented

system of VET funding, the Australian Government will cap the amount students

will contribute to their education through a VET student loan, but there is no

guarantee to a provider that they will receive enough subsidy funding to cover

the cost of education, as these subsidies are set independently at a state or

territory level. This basic design difference raises the question as to whether

approaches used in higher education such as the HELP framework are appropriate

in shaping the VET market.

The

effectiveness of regulation

ASQA is the national regulator for the VET sector. The

Department of Education and Training administered the VET FEE-HELP scheme, and

will now administer the VET student loans scheme. Existing RTOs in Victoria and

Western Australia who wish to access VET student loans may have a range of

compliance issues as identified by their state based regulators. In considering

whether the Student Loans Bill will provide a more effective regulatory

approach than found under VET FEE-HELP, the regulatory powers available, regulators’

capacity to use those powers, and the systemic nature of VET have to be

examined.

A new

regulatory regime – more of the same?

The VET FEE-HELP Reform Bill established new regulatory

powers for the VET FEE-HELP scheme, including monitoring powers, investigation

powers, infringement notices, and the use of civil penalties.[112]

These powers have only been in effect since 1 January 2016 and there has been

no review or audit of how they have been used and whether they have been

effective in addressing inappropriate provider behaviour.

Part 8 of the Student Loans Bill extends these powers

to include enforceable undertakings and injunctions. As with the monitoring and

enforcement powers introduced by the VET FEE-HELP Reform Bill, the use of these

powers is governed by the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014.

Except in the case of enforceable undertakings and injunctions, these powers

may be utilised by both Departmental and ASQA officers. Enforceable

undertakings and injunction action is reserved to the Department of Education

and Training only.

Part 9 sets out an extensive information disclosure

regime, allowing specified officers to use and disclose information in relation

to the VET student loans scheme to certain agencies, bodies or persons, in

relation to law enforcement, and to assist in the provision of vocational

education and training. This information disclosure regime builds on amendments

recently made through the Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (2016 Measures No. 1) Bill 2016.[113]

As with that Bill, there is no requirement for the Secretary to publish VET

student loan scheme information to allow for better external research or

assessment of the scheme, nor is there provision in Part 9 for the stated aims

of the information disclosure regime, or a legislated review requirement to

assess whether these aims have been met.[114]

Regulatory

capacity

To date there has been no recent public review of ASQA, the

Department, the state-based regulators in Victoria or WA, or their capacity to

collaborate and share data. With the significant changes to the VET regulatory

landscape since the introduction of measures like VET FEE-HELP and the

establishment of ASQA itself, a first principles approach might be to examine

the powers of each entity and see if they are fit for the current environment.

It does appear that collaboration, and a concern over remit

and bureaucratic boundaries, may have hampered an effective approach to VET

FEE-HELP compliance. In an answer to a question on notice emerging out of the Senate

Inquiry into the VET Student Loans Bills, ASQA revealed that a cross-agency

round table to discuss a joint approach to VET FEE-HELP did not occur until 12

November 2014, and an analysis of existing VET FEE-HELP complaints against the

various responsibilities of ASQA, the Department of Education and Training, and

the Australian Competition and Consumer commission was not undertaken until 8

December 2014.[115]

The proposed new compliance regime does not resolve the fundamental lack of

clarity over responsibility.

It’s also useful to note in this context that recent court

action against RTOs has been commenced by the Australian Competition and

Consumer Commission, viewing unethical RTO practices as potential breaches of

consumer law, rather than the VET regulatory framework.[116]

This raises further questions as to whether ASQA or the Department have an

adequate regulatory capacity to deal with the sector.

A further question is whether regulators have adequately

used their existing powers. It may not be that new powers provided by the

Student Loans Bill are needed, but that there has been an unwillingness or

inability on the part of the bureaucracy to provide effective monitoring and

remedial action. In a submission to the Senate Inquiry on the VET Student Loans

Bills, a former SES officer with the Department of Education and Training

identified that both the Department and ASQA had existing powers to seek

information, revoke funding approval, undertake audits and hold providers

accountable under the relevant legislation: the problem was not that these

powers did not exist, but that they were not used.[117]

Creating new powers, as the Student Loans Bill does, does not address this

issue.

What may explain an unwillingness to undertake regulatory

activity? Part of it may simply be capacity. Previous reforms, such as the

banning of inducements, did not appear effective: since the introduction of the

new VET Guidelines across 2015, media reports continue to indicate that

providers are still offering students now-prohibited inducements such as

laptops, raising ongoing questions as to the capacity of the Department to

properly enforce regulatory changes.[118]

Further, the Department of Education and Training is not a regulator, but a

department of state, a policy maker. Its role as program manager of VET

FEE-HELP and VET student loans may not be appropriate, depending on whether the

aim is to improve compliance, or improve outcomes.

Inputs and

outcomes

Both the Department and ASQA appear to operate in line with

what has been called the ‘cake making approach,’ which is an input-based

system.[119]