Bills Digest no. 36,

2016–17

PDF version [761KB]

Kai Swoboda and Tarek Dale

Economics Section

9

November 2016

This Bills Digest updates an earlier

version dated 31 March 2016.

Contents

History of the Bill

Purpose of the Bill

Background

What is conflicted remuneration?

Life insurance industry, products and

remuneration arrangements

Figure 1: Life insurance

remuneration models, 2011–2013 averages

Brief history of the future of

financial advice changes

Policy development

Industry attempts at self-regulation

ASIC review

Trowbridge Review

Interim report

Final report

Financial System Inquiry

Interim report

Final report

Government response to Financial

System Inquiry

Final policy decision and draft

legislation

Broader policy considerations

Developments since the earlier Bill

CommInsure Scandal

Life insurance code of practice

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Corporations and Financial Services

Committee consideration

Senate Economics Legislation

Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Delayed start date

Why regulate life insurance

remuneration arrangements?

Consumer interests

Form of regulation

Facilitative provisions

Allowable commissions and clawbacks

Benefit ratio requirements

Clawback requirements

Transitional arrangements

2021 Review

Date introduced: 12

October 2016

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Sections

1–3 on Royal Assent; Schedule 1 on 1 January 2018.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2016.

History of

the Bill

A similar (but not identical) version of this Bill was

introduced in the 44th Parliament. The Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 (the earlier Bill) was introduced on 11 February

2016, and progressed to the Senate, but lapsed at the prorogation of the 44th

Parliament.[1]

The differences in the two versions of the Bill are outlined below.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 (the Bill) is to amend the Corporations Act

2001 to:

- remove

the current exemption from the ban on conflicted remuneration for benefits paid

in relation to certain life risk insurance products and

- enable

the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to make a

legislative instrument to permit benefits in relation to life risk insurance

products to be paid—provided that certain requirements are met.

Background

What is conflicted

remuneration?

Division 4 in Part 7.7A of the Corporations Act sets

out a general ban on remuneration arrangements for financial advisors on the

sale of financial advice and financial products to certain consumers. The

rationale for the ban is that, because of the nature of the benefit or the

circumstances in which it is given, the remuneration arrangements could

reasonably be expected to influence the choice of product or advice given.[2]

The general aim of these provisions—which were part of the ‘Future of Financial

Advice’ (FOFA) arrangements implemented by the Gillard Government—was to more

closely align the interests of those who provide financial product advice to

retail clients with the interests of their clients, and improve the quality of

advice these clients receive.[3]

Section 963B of the Corporations Act provides some

exemptions from the general ban on conflicted remuneration in certain

circumstances. These exemptions include, amongst other things, where the benefit

relates solely to a general insurance product[4]

or where the benefit relates solely to a life risk insurance product, other

than a group life policy for members of a superannuation entity or default

superannuation fund.[5]

The exemption for life insurance outside of superannuation,

which was included as part of the FOFA changes, was based on concerns about

affordability of life insurance and the potential for under‑insurance.[6]

Life

insurance industry, products and remuneration arrangements

As at December 2015 there were 28 registered life insurers

operating in Australia,[7]

and the sector had net premium income in the 2015–16 financial year of $56.7 billion.[8]

Life insurance generally covers a range of insurance

products including:

- life

cover—also known as term life insurance or death cover, pays a set amount of

money when the insured person dies

- total

and permanent disability (TPD) cover—covers the costs of rehabilitation, debt

repayments and the future cost of living if the insured person is totally and

permanently disabled. TPD cover is often bundled together with life cover

- trauma

cover—provides cover in the event of a diagnosis of a specified illness or

injury. These policies include the major illnesses or injuries that will make a

significant impact on a person's life, such as cancer or a stroke. It is also

referred to as ‘critical illness’ cover or ‘recovery’ insurance and

- income

protection—replaces the income lost through an inability to work due to injury

or sickness.[9]

Consumers generally purchase life insurance in one of three

ways: through an advice provider (adviser); directly from an insurer; or

through their superannuation fund and the group life cover offered by the fund.[10]

As at 30 June 2013 the Australian Securities and Investments

Commission (ASIC) found that, for 12 life insurers participating in an ASIC

survey, there were 2.6 million policies in force that were purchased

through an advice provider (adviser).[11]

At this time, life only and income protection policies were the most common

policies in force, comprising 32 per cent and 21 per cent of the

total policies in force.[12]

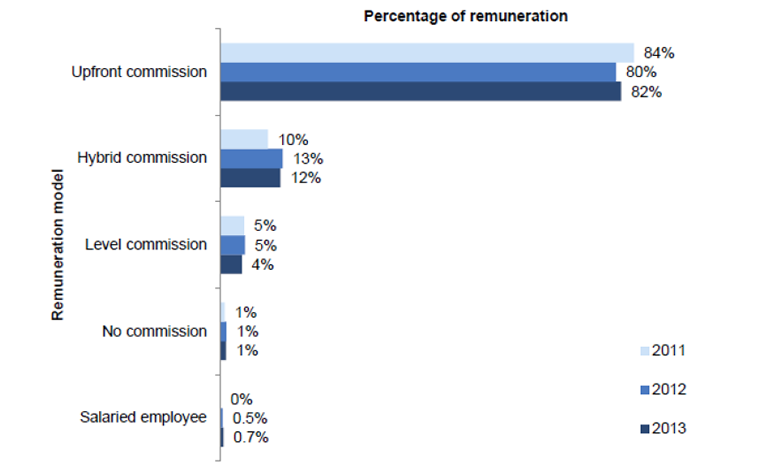

For life insurance distributed under personal advice models,

advisers are typically paid under commission arrangements. In 2014 ASIC noted

that upfront commission models—in which advisers were paid an amount upon the

sale of a new premium—were the dominant remuneration arrangement by a

significant margin, with 82 per cent of the remuneration in the industry

in 2013 derived from these amounts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Life insurance remuneration models, 2011–2013 averages

Source: Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC),

Review

of retail life insurance advice, report, 413, 9 October 2014,

pp. 26–27.

Brief

history of the future of financial advice changes

The FOFA reforms were a package of amendments to change how

financial advice is delivered to clients including:

- how financial advisers behave in relation to providing advice

- how clients are charged for this advice and

- the disclosure of fees to clients.

The FOFA reforms constituted the Rudd and Gillard

Governments’ response to the 2009 report by the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Corporations and Financial Services of its Inquiry into Financial

Products and Services (PJC report).[13]

The impetus for the PJC inquiry was a number of significant corporate

collapses, including Storm Financial and Opes Prime.[14]

The FOFA reforms were introduced into the Parliament in late

2011 and implemented by two key pieces of legislation:

enhanced the requirement for disclosure of fees and services

associated with ongoing fees[15]

and

enhanced the ability of ASIC to supervise the financial

services industry, through changes to its licensing and banning powers for

financial advisers[16]

and

required those persons who are providing personal financial

advice to retail clients to act in the best interests of their clients, and to

give priority to their clients’ interests[17]

imposed a prospective ban on conflicted remuneration

structures[18]

applied existing regulatory mechanisms under the Corporations

Act more directly to individual advisers as well as to licensees.[19]

The implementation date for most of the FOFA reforms was

originally 1 July 2012. However, Government amendments during the passage

of the legislation provided that the provisions would be voluntary until 1 July 2013,

after which time compliance with the relevant requirements was mandatory.[20]

Upon coming to office, the Abbott Government sought to

make a number of changes to some aspects of the FOFA arrangements through the Corporations

Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014, which was

introduced in the House of Representatives on 19 March 2014.[21]

Some of the proposed changes included:

- removing

the need for clients to renew their ongoing fee arrangement with their adviser

every two years (also known as the ‘opt-in’ requirement)

- making

the requirement for advisers to provide a fee disclosure statement only

applicable to clients who entered into their arrangement after 1 July 2013

- removing

the ‘catch-all’ provision, from the list of steps an advice provider may take

in order to satisfy the best interests obligation

- better

facilitating the provision of scaled advice and

- providing

a targeted exemption for general advice from the ban on conflicted remuneration

in certain circumstances.[22]

Some of these proposals were controversial.

While the Bill was before the Parliament, the Government

announced that it would implement some of the changes by regulation.[23]

These amendments were implemented through the Corporations Amendment

(Streamlining Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014, which commenced on 1

July 2014.[24]

On 19 November 2014, the Regulation was disallowed by the Senate.[25]

The Government then remade a number of time-sensitive

elements of the disallowed Regulation. These changes were implemented through

the Corporations Amendment (Revising Future of Financial Advice) Regulation

2014 (dated 11 December 2014) and the Corporations Amendment (Financial Advice)

Regulation 2015 (dated 25 June 2015).[26]

The Regulations commenced on 16 December 2014 and 1 July 2015

respectively.

The Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of

Financial Advice) Bill 2014, including amendments made by the Government, was

passed by the House of Representatives on 28 August 2014. The Bill, with

further Government amendments, was passed by the Senate on 24 November

2015 and agreed to by the House of Representatives on 1 March 2016.[27]

The key changes that were proposed in the Bill as introduced but not included

in the Bill as finally passed by the Parliament were:

- changes

to the Statements of Advice requirements

- repeal

of the requirement that licensees send fee disclosure statements to pre-1 July

2013 clients

- repeal

of the opt-in requirement for continuing an ongoing fee arrangement between a

fee recipient and a client

- changes

to the best interests duty and scaled advice and

- the

general advice exemption from conflicted remuneration.[28]

Policy

development

The arrangements proposed by the Bill are a response to

concerns held over a number of years about remuneration arrangements in the

life insurance industry. These concerns were considered as part of the FOFA

reform process.

While self-regulation was first proposed by the financial

services industry in 2011, the idea did not receive universal industry support.

This then led to a life insurance industry-commissioned review, which

overlapped with the Government’s financial system review and ASIC research.

Further consultation by the Government after these processes

concluded then contributed to the design of the measures included in the Bill.

Industry

attempts at self-regulation

At the same time as the development of the FOFA package of

measures in 2010 and 2011, the financial services industry was examining

remuneration arrangements in life insurance to address issues associated with

‘churning’—whereby consumers with an existing life insurance policy are sold a

new policy by a financial adviser that has no net benefit for the consumer.[29]

While churn can be a measure of competition within an industry and indicate

that choice is exercised by consumers, relatively high levels of churn in some

industries may also be associated with concerns about inappropriate marketing

strategies or customer dissatisfaction with a supplier.

In August 2011, the Financial Services Council (FSC)

recognised that churning impacted on both the quality and cost of life

insurance products for consumers and on the profitability of the industry, with

the CEO of the FSC noting:

Advisers that engage in churning do so to access the upfront

commission on the sale, in the knowledge that the new policy provides

essentially equivalent cover and benefits for the client, to the policy that

has been replaced.

The practice also creates cost pressures for life insurance

premiums that are simply wasteful and unnecessary.

This practice is not in the interests of consumers and the

FSC has taken the clear view that it is inconsistent with the statutory

requirement for financial advisers to act in their clients’ best interests.

While this practice is not widespread, it is significant

enough an issue to warrant industry action.[30]

At this time, the FSC proposed the development of a

voluntary industry standard (which would apply to members of the FSC) to

address the practice of ‘churning’.[31]

The FSC proposal included:

- the

removal of ‘takeover terms’ (that is, banning the practice of the relaxation of

the standard underwriting process for replacement business) for a policy or a

group of policies that are transferred by an adviser between insurers and

- the

establishment of a consistent adviser responsibility period across the industry

of two years—with 100 per cent commission clawback if the policy lapses with an

insurer within one year, and 50 per cent commission clawback if the policy

lapses with an insurer during the second year.[32]

When this proposal was announced, the FSC intended that it

would be finalised in 2012 ‘with an implementation date that would be

consistent with the FOFA reforms’.[33]

One year later, in August 2012, the FSC finalised its

proposed industry standard, which was to be effective from 1 July 2013.[34]

Key elements of the proposed standard included:

- Where an advised policy

lapses within three years of commencement, a three year adviser responsibility

period will apply;

- A tiered commission

claw-back provision will be introduced as follows:

- 100% of remuneration paid

by an insurer to an adviser if the policy lapses within the first year;

- 75% of remuneration paid by an insurer if the policy

lapses within the second year; and

- 50% of remuneration paid by an insurer if the policy

lapses within the third year.[35]

By February 2013 however, the implementation of the

standard had been abandoned by the FSC.[36]

The CEO of the FSC was reported to have attributed the decision to ‘no longer

having the unanimity on this approach’ and that ‘the proposed framework raised

a complex set of factual, legal and economic issues from a competition

perspective, which meant that it would have required regulatory approval in

order to be implemented’.[37]

The CEO noted that the FSC ‘remains committed to ensuring a sustainable life

insurance sector which will deliver outcomes for the community and the industry

participants’.[38]

ASIC review

On 9 October 2014, ASIC published a review of retail

life insurance.[39]

The review, conducted between September 2013 and July 2014, examined:

- how

life insurance is sold by advisers

- how

advisers are remunerated for that advice

- the

drivers behind product replacement advice to consumers and

- the

quality of the personal advice consumers receive.[40]

The purpose of the review, described as a ‘proactive

surveillance of life insurance advice’ in the 2014–15 ASIC annual report, was

‘to better understand the quality of advice consumers receive’.[41]

The ASIC review noted that life insurance policies are

lapsing—when a policy ceases due to non-payment or cancellation by the client—at

high rates, with policy lapses doubling from approximately seven per cent in

the first year to 14 per cent in the second year.[42]

After the initial spike, lapse rates remain high (above 14 per cent) for

the next three years before tapering.[43]

The factors for these higher lapse rates included:

- product

innovation by insurers, such as changing actuarial assumptions at underwriting

or the redesign of key policy features such as definitions and exclusions,

which leads to the repricing of policies

- age-based

premium increases affecting affordability, and

- incentives

for advisers to write new business or rewrite existing business to increase

commission income.[44]

The ASIC review also found a correlation between high lapse

rates and upfront commission models.[45]

The main recommendations of the review did not necessarily

advocate a stronger role for government in regulating remuneration

arrangements. Instead, the recommendations were for insurers and financial

advisers to examine, individually or as an industry, the business models and

remuneration arrangements:

We recommend that insurers:

(a) address misaligned incentives in their distribution

channels;

(b) address

lapse rates on an industry-wide and insurer-by-insurer basis (e.g. by

considering measures to encourage product retention); and

(c) review

their remuneration arrangements to ensure that they support good-quality

outcomes for consumers and better manage the conflicts of interest within those

arrangements.

We recommend that AFS licensees:

(a) ensure that remuneration structures support good-quality

advice that prioritises the needs of the client;

(b) review their business models to provide incentives for

strategic life insurance advice;

(c) review the training and competency of advisers giving

life insurance advice; and

(d) increase

their monitoring and supervision of advisers with a view to building ‘warning

signs’ into file reviews and create incentives to reward quality, compliant

advice.[46]

Trowbridge Review

Following the release of the ASIC review, in December 2014, the

Association of Financial Advisers (AFA) and the FSC established a Life

Insurance and Advice Working Group headed by former APRA member John

Trowbridge, to review the ASIC report.[47]

Interim

report

An interim report was published by the FSC on 17 December

2014.[48]

The interim report put forward five models to be considered for direct adviser

remuneration:

- level

commissions only (no extra commission in year one) and no other direct

remuneration

- hybrid

commissions as currently understood as the maximum commissions (for example,

dictating a maximum upfront commission of 80 per cent and level commission

thereafter)

- modified

hybrid comprising initial remuneration of a combination of commission at a

level less than the current hybrid plus a fixed dollar payment. Renewal

commissions could be as per current hybrid arrangements

- level

plus fees comprising level commissions, at a rate to be considered,

supplemented by an initial payment in the nature of a fee from the insurer to

the adviser. Such a payment would not be a commission but a fee in the nature

of cost recovery or expense reimbursement and

- level

funded as a variation on ‘level’ where the commissions are level but to offset

initial costs, on each policy inception the insurer lends the adviser funds

that are repayable over say three to five years from renewal commissions.[49]

Final

report

The final report was released on 26 March 2015.[50]

In relation to remuneration arrangements, the final report proposed a

remuneration model that was based on a fixed level of commission (maximum

20 per cent of premiums) supplemented by an ‘initial advice payment’.[51]

The recommendations were in two parts, with a ‘reform model’ (commencing from a

date in 2018) supported by a three-year transition plan:

The Reform Model can be described as level commissions

supplemented by an Initial Advice Payment available at a client’s first policy

inception and then no more often than once every five years, where:

- the

level commission is a maximum of 20% of premiums;

-

the

Initial Advice Payment (IAP) is paid by the insurer to the adviser on a per

client basis (which would generally mean the insured life);

-

the

IAP is available to the adviser when a client first takes out a life insurance

policy and subsequently no more often than once every five years and then only

when a new policy is being taken out (the “five year rule”); and

- the

IAP is a maximum of $1,200 or, for customers with annual premiums below $2,000,

no more than 60% of the first year’s premiums.

...

The Transition Plan has two phases –

The first phase is where the five year rule is to apply on a

best endeavours basis by insurers and licensees. It is recommended to commence

as soon as possible, say 30 June 2015. In all other respects current

arrangements would remain in place pending the second phase.

The second phase will require some form of regulation, to

begin from a suitable date in 2016 and is where –

- the

maximum commissions are to be on the current hybrid basis with a cap, so that

the maximum initial commission is 80% of premiums capped at $8,000 and maximum

renewal commission is 20%;

- for

the purposes of the five year rule, the initial commission is to be treated as

a recurring component of 20% and an IAP of 60% of premiums;

- this

arrangement is to continue for two years pending full introduction of the Reform

Model.[52]

On 25 June 2015, the then Assistant Treasurer welcomed the

release of the Trowbridge Review and noted that the Government would consider

the proposals in the context of its response to the Financial System Inquiry.[53]

Financial

System Inquiry

The Financial System Inquiry (also referred to as the

‘Murray Inquiry’ after its chair Mr David Murray AO), conducted over the period

late 2013 to late 2014, included some consideration of remuneration

arrangements in the financial services industry.

Interim

report

In its interim report, released on 15 July 2014, the

Murray Inquiry noted that ‘the principle of consumers being able to access

advice that helps them meet their financial needs is undermined by the

existence of conflicted remuneration structures in financial advice’.[54]

The interim report also sought some additional information about the extent of

underinsurance.[55]

Final

report

In its final report, released on 7 December 2014, the

Murray Inquiry made some specific recommendations about remuneration

arrangements in the life insurance industry.[56]

The final report states:

With the exception of group life insurance policies inside

superannuation and an individual life insurance policy for a member of a

default fund, life insurance products are exempt from the [future of financial

advice] ban on commissions. This allows individual life policies to be sold

with high upfront commissions, creating an incentive for advisers to make a

sale, rather than provide strategic advice. For example, these policies can have

100–130 per cent of the first year’s premium payable as upfront commissions,

with an ongoing trail commission of around 10 per cent.

...

Upfront commissions can affect the quality of advice. ASIC

found that 96 per cent of advice rated as a ‘fail’ was given by advisers paid

under an upfront commission model. ASIC also found high upfront commissions

encourage advisers to replace a consumer’s policy rather than retain it. In

some cases, this may result in inferior policy terms. To date, industry

approaches to address the issues in life insurance have not worked.[57]

The Murray Inquiry recommended that a level commission

structure be implemented through legislation requiring that an upfront

commission is not greater than the ongoing commission.[58]

The final report also noted:

Alternative models of remuneration, such as delayed vesting

of commissions and clawback arrangements, may simply delay the issue of churn

and are complex. At this stage, the Inquiry does not recommend removing all

commissions, as some consumers may not purchase life insurance if the advice

involves an upfront fee. However, if level commission structures do not address

the issues in life insurance, Government should revisit banning commissions.

The Inquiry has not determined the percentage amount of the

level commissions that should apply in the life insurance sector. This should

be left to the market and industry.[59]

Government

response to Financial System Inquiry

The Government response to the Murray Inquiry was released

on 20 October 2015.[60]

The Government response noted the release of the Trowbridge final report which

had been delivered during the Murray Inquiry and proposed to proceed with the

life insurance industry’s proposed reforms:

The Government agrees more can be done to better align the interests

of financial firms and consumers. However, we intend to take a different

approach to that recommended by the Inquiry for retail life insurance.

We support the retail life insurance industry’s proposed

reforms as announced by the then Assistant Treasurer on 25 June 2015. The

Government will consider the extent to which legislation and/or action by ASIC

may be necessary to implement the industry agreement.

A Government review in 2018 will consider whether the new

industry arrangements for life insurance advice have better aligned the

interests of firms and consumers. If the review suggests further reform,

consideration would be given to the Inquiry’s recommendation for a level

commission structure or further extending the existing Future of Financial

Advice provisions on conflicted remuneration to life insurance advice.[61]

Final

policy decision and draft legislation

On 6 November 2015 the Assistant Treasurer announced that

the Government had reached agreement with the life insurance industry about remuneration

arrangements.[62]

Key elements of the announced package included:

- phasing

down upfront commissions to a maximum of 80 per cent from 1 July 2016; 70 per

cent from 1 July 2017 and then 60 per cent from 1 July 2018, together

with a maximum 20 per cent ongoing commission and

- introducing

a two year retention (‘clawback’) period as follows:

- in

the first year of the policy, to 100 per cent of the commission on the first

year’s premium and

- in

the second year of the policy, to 60 per cent of the commission on the first

year’s premium.[63]

Treasury released draft legislation for consultation on

3 December 2015, with submissions due by 4 January 2016.[64]

The Assistant Treasurer noted in her second reading speech to the earlier Bill that

over 20 submissions to the draft legislation had been received.[65]

At the date of publication of this Bills Digest, submissions to the draft

legislation had not been published by Treasury.

On 15 December 2015 ASIC released a consultation

paper seeking feedback on aspects of the proposed legislative instrument that

would underpin much of the detailed arrangements that would be facilitated by

the Bill.[66]

Comments on the consultation paper closed on 29 January 2016.[67]

Included in the consultation paper were the following proposed key thresholds

in relation to maximum commissions and clawback arrangements:

- transitional

arrangements for the setting of the maximum level of commissions at 80 per

cent of the premium in the first year of the policy from July 2016, reducing to

70 per cent from 1 July 2017 and then to 60 per cent from 1 July 2018

- an

ongoing commission for policy renewals will be set at a maximum of 20 per

cent of the total of the premium paid for the renewal and

- a

two-year clawback period for policies that have lapsed, with 100 per cent

of the commission repaid if the policy lapses in the first year and 60 per

cent of the commission repaid if the policy lapses in the second year.[68]

These key thresholds are consistent with the Government’s

6 November 2015 announcement.

Broader

policy considerations

The Government’s 6 November 2015 announcement made

reference to several other policies that were part of a broader approach to

improving the quality of financial advice for life insurance and the efficiency

of the life insurance industry. These included:

- a

Life Insurance Code of Conduct to be developed by the FSC by 1 July 2016. The

Code would set out best practice standards for insurers, including in relation

to underwriting and claims management

- financial

services industry to have responsibility for widening Approved Product Lists

through the development of a new industry standard.[69]

This industry standard will be a joint effort of all industry participants, led

by the FSC

- ASIC

to commence a review of Statements of Advice from the second half of 2016, with

a view to making disclosure simpler and more effective for consumers as well as

assisting advisers to make better use of these documents. The review of

Statements of Advice will also consider whether the disclosure of adviser

remuneration could be more effective, including prominent upfront disclosure of

commissions and

- amendments

to the Corporations Act to facilitate the rationalisation of legacy

products in the life insurance and managed investment sectors, with further

analysis of the taxation implications explored in the context of the

Government’s Taxation White Paper process.[70]

A broader range of measures to improve the standard and

quality of financial advice, through mandating educational standards and

professional development standards, is also being pursued by the Government as

part of its response to the Financial System Inquiry.[71]

Developments

since the earlier Bill

CommInsure

Scandal

CommInsure is one of Australia’s largest life insurance

providers, with approximately four million policy holders.[72]

On 7 March 2016, Four Corners reported statements by CommInsure’s chief

medical officer that the provider had avoided making payouts.[73]

In April 2016 ASIC commenced investigations into CommInsure’s life insurance

business,[74]

and an industry wide review of life insurance claims handling practices.[75]

At the time of writing the investigation into CommInsure was

still underway. ASIC stated:

ASIC has undertaken an extensive range of enquiries into the

concerns raised. Enquiries are ongoing and no comment on potential outcomes

will be made at this time. Given the wide ranging and often complex nature of

these matters, ASIC's investigation is anticipated to continue for some time.[76]

ASIC completed its industry-wide investigation into life

insurance claims handling practices on 12 October 2016.[77]

The review:

... examined claims handling practices and claims outcomes in

the life insurance sector. We sought to identify whether there were systemic

issues across the industry, as well as more specific issues relating to particular

products or insurers.[78]

While the review ‘did not find evidence of cross-industry

misconduct’, it did:

... identify issues of concern in relation to declined claim

rates and claims handling procedures associated with:

(a) particular

types of policies, notably TPD;

(b) particular

insurers (typically for particular policy types); and

(c) particular

causes for consumer disputes.[79]

The review identified a number of ‘key areas of action’,

including:

- additional

public reporting on claims and claims outcome data

- strengthening

the legal framework for claims handling

- targeted

follow-up ASIC reviews, and

- stronger

industry standards.[80]

Life

insurance code of practice

Following the Assistant Treasurer’s announcement on 6

November 2015, the Financial Services Council (FSC) consulted on and

subsequently released a life insurance code of practice on 11 October 2016.[81]

The Code applies to FSC members, and other industry participants who adopt the

Code through a formal agreement. The Code will be reviewed at least every three

years by the FSC, and enforced by the Life Code Compliance Committee, which

will be comprised of a consumer representative, an industry representative, and

an independent chair.[82]

The Compliance Committee can require ‘rectification steps’, and publish

information where these are not complied with.[83]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services

On 14 September 2016, the Senate referred an inquiry into

the life insurance industry to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Corporations and Financial Services, for report by 30 June 2017.[84]

At the time of writing the Committee had not yet held public hearings or begun

publishing submissions.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Economics Legislation Committee

The earlier Bill was referred to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee (Economics Committee) for inquiry and report by

15 March 2016.[85]

The Economics Committee received a similar form letter from 209 stakeholders

and 56 other submissions.[86]

Most submissions originated from persons working in the life insurance industry

as advisers. They expressed a number of concerns, for instance:

- the

legislation would have the effect of exacerbating Australia’s ‘chronic

under-insurance crisis’[87]

- the

amendments would create ‘barriers and impediments’ to those financial advisers

who seek to improve education, operate honestly and in a trustworthy manner for

the benefit of consumers[88]

so that the industry will see a reduction in adviser numbers[89]

and the Bill will not provide any identifiable benefits for consumers.[90]

The Economics Committee recommended that the Bill be

passed.[91]

In additional comments, Labor members of the Committee noted the following

concerns raised in submissions to the inquiry:

- the

reviews preceding the reform focused on churning, and not appropriate methods

of dealing with rogue advisers; the data sample used in ASIC's review was

inadequate; and not all stakeholders were consulted

- the

reform will adversely affect consumer choice and competition, and will see an

increase in the cost of life insurance, coupled with the implementation of fees

for advice and

- the

life insurance advice industry will see a decline in adviser numbers and an

increase in the market share of large institutions like banks.[92]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills made

no comment on the earlier Bill.[93]

The Committee has not yet reported on the current Bill.

Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[94]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considered

the earlier Bill and concluded that it did not raise human rights concerns.[95]

The Committee has not yet reported on the current Bill.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

When the earlier Bill was debated in the House of

Representatives on 3 March 2016, the Australian Labor Party (ALP)

indicated that it would support it.[96]

While the ALP noted some issues of concern (such as separating out the cost of

stamp duty and other government taxes in life insurance products), the overall

position of the ALP was:

... [it] will make incremental improvement to the life

insurance remuneration structures. We know that that view is not universal in

the sector or in the community but we think all of these Bills are, on-balance

calls and we think, on balance, this Bill is worth supporting.[97]

As noted previously, while ALP Senators made some

additional comments in the Senate Economics Legislation Committee inquiry into

the earlier Bill, the ALP Senators did not propose to oppose the earlier Bill.[98]

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, no other

non-government parties or independent Senators or Members had publicly expressed

a position on the Bill.

Position of

major interest groups

In her second reading speeches on both versions of the Bill,

the Minister specifically acknowledged the work of the AFA, the Financial

Planners Association (FPA) and the FSC ‘in working together to achieve sensible

reforms for the sector which will benefit consumers through the provision of

more appropriate advice and the long-term sustainability of the industry’.[99]

The AFA has generally supported the development of the

regulatory package. On 6 November 2015 the AFA welcomed a reduction in the

clawback period from three years to two years, noting that this ‘brings greater

fairness to the [Life Insurance Framework] and that ‘[t]o succeed in having

this reduced to two years is a great relief for our members, particularly those

that own and operate small businesses’.[100]

The FSC comments on 6 November 2015 also supported the

proposed arrangements, noting that the proposed changes were ‘a positive first

step in lifting industry practices to improve consumer outcomes’.[101]

In a media release on 12 October 2016 the FSC also welcomed the reintroduction

of the Bill, stating:

These legislative provisions are on track to limit upfront

commissions to advisers and ban conflicted remuneration provisions on life

insurance products ... The life insurance remuneration bill will reduce conflicts

and misaligned incentives by significantly reducing upfront commissions,

extending the responsibility period to two years and prohibiting conflicted

remuneration across life insurance. These reforms apply across life insurance

and apply to all advisers equally.[102]

The FPA also welcomed the proposed arrangements, noting that

they were ‘a sensible outcome that will ensure the sustainability of the

industry’.[103]

The FPA noted that the setting of the clawback period of two years was ‘a

result of combined representation by the AFA and FPA’.[104]

National Seniors Australia (NSA) supports the intent of

the regulatory package.[105]

However, while recognising that the package was a compromise solution, NSA

considered that ASIC should be given the power to set level commissions and

zero commissions and also that the clawback provisions should be strengthened

to specify a minimum three-year period.[106]

Consumer organisation Choice, also commenting on the

6 November 2015 announcement, was generally supportive of the regulatory

package but was ‘disappointed that the reforms have been watered down since

they were announced in June’.[107]

Choice considered that the change from a three year clawback period was ‘the

result of an aggressive lobbying campaign by financial advisers seeking to

protect the conflicted remuneration models upon which their industry is built’.[108]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that the financial impact

on the Commonwealth of the measures proposed by the Bill is ‘nil’.[109]

However, the Regulation Impact Statement acknowledges:

For large and medium sized licensees, there will be

implementation costs associated with updating IT and other systems. It is

assumed that small licensees do not have advanced IT systems and so the IT

costs are not likely to be material. All licensees will have additional costs

associated with monitoring compliance with the new regulations.

Individual financial advisers will incur a small cost

associated with updating their knowledge of the remuneration arrangements,

including clawback.

It is estimated that the increase in annual compliance costs

for the industry as a whole will amount to $27.8 million.[110]

Key issues

and provisions

Delayed

start date

The commencement date for the earlier Bill, introduced in

the 44th Parliament, was 1 July 2016, with an unlegislated ASIC review intended

for 2018.[111]

The commencement date for the current Bill is 1 January 2018, with an ASIC

review intended in 2021. The Minister stated:

The government has continued to listen to feedback raised by

industry and key stakeholders during consultation on the life insurance reforms

... the government has amended the commencement date of the reforms to 1 January

2018. This will enable the government to remove the generous grandfathering

that was available under FoFA, which allowed advisers to continue to receive

conflicted remuneration for the length of their enterprise agreements plus an

additional 12 months.

The government wants these reforms to start as soon as

possible and to apply equally to all advisers, whether they own their own small

business or they are employed by a major bank. To achieve this, the reforms

will commence 12 months after the entire reform package is settled. This

will provide advisers with 12 months to renegotiate their collective agreements

to be consistent with the new legislation.[112]

The Corporations Regulations 2001 specify that if a

benefit is paid under an enterprise agreement that was entered into before 1

July 2013, then certain restrictions on conflicted remuneration do not apply

(are ‘grandfathered’) for a specified period.[113]

Why

regulate life insurance remuneration arrangements?

In her second reading speeches on both Bills, the Minister

noted that the proposed changes ‘strike the right balance between protecting

consumers and recognising the need for ongoing viability and industry

stability’.[114]

The balance needs to be struck in respect of two matters:

- first,

balancing the objective for more people to take out life insurance and the

remuneration arrangements that may contribute to inappropriate advice and life

insurance products being chosen by a consumer and

- second,

the form of regulation and the extent of government intervention required to

achieve the desired outcomes.

Consumer

interests

As noted previously, the exemption for life insurance

outside of superannuation from the conflicted remuneration arrangements under

FOFA was largely based on concerns about affordability and the potential for

under-insurance.[115]

Commission-based arrangements for the sale of life

insurance, where products can be complex and there exists asymmetric

information between buyer and seller about remuneration arrangements, can lead

to greater incentives to provide biased advice to unsophisticated potential

consumers.[116]

Economic analyses suggest that a commission-based model can be superior to the

alternative upfront fee-for-service approach, although this result can depend

on the extent to which different consumers are prepared to directly pay for

advice and the value they attach to the advice.[117]

The approach proposed by the Bill dilutes, but does not

remove, the influence of commission-based remuneration arrangements in part of

the life insurance industry. It also steers a middle course through the

proposals of the Trowbridge final report for a fixed level of commission

(maximum 20 per cent of premiums) supplemented by an ‘initial advice

payment’ and the recommendations of the Murray Inquiry which were for a level

commission structure requiring that an upfront commission is not greater than

the ongoing commission.[118]

Form of

regulation

There has been some history of self-regulation in parts of

the financial services industry through the development of industry codes of

practice or codes of conduct. The first such financial services code was adopted

in 1989 whilst a code covering life insurance was developed in 1995.[119]

Initially, such codes were viewed largely as part of an ‘enrolment’ process to

draw industry into the regulatory system.[120]

While such codes are sometimes viewed as a defensive mechanism by industry, it

is also arguable that they have become more forward-looking initiatives, ‘focusing

on improving standards and providing genuine consumer protection.[121]

As noted previously the life insurance industry, through the

FSC, had attempted to develop an industry standard to address issues related to

churning and inappropriate advice. However, although the industry has

introduced a life insurance code of practice, the failure of the industry to

self‑regulate in relation to remuneration has arguably necessitated the

government stepping in to regulate remuneration arrangements.

The Trowbridge final report supported government

intervention, noting:

It is essential for the integrity of the recommendations on

adviser remuneration and licensee remuneration that there be some kind of

externally imposed regulation on the industry. An effective form of this

regulation, given the nature of the regulation required and the ability of ASIC

to maintain an associated compliance regime, is likely to be the imposition by

ASIC of licensing conditions on life insurers. These conditions would oblige

all life insurers, and through them all licensed adviser groups (generally

referred to as licensees in this report) by means of the contractual

relationships between insurers and licensees, to conform to the Reform Model,

the Transition Plan and the avoidance of conflicts of interest by licensees.[122]

The Murray Inquiry also backed implementing its

recommendations for a level commission structure through legislation.[123]

Facilitative

provisions

The main elements of the Bill amend the conflicted

remuneration framework in Part 7.7A of the Corporations Act to empower

ASIC to make a legislative instrument which will regulate benefits paid to life

insurance brokers and advisers on the sale of life insurance products. These

include some key concepts and definitions.

Allowable

commissions and clawbacks

Existing section 963E of the Corporations Act bans

a financial services licensee from accepting conflicted remuneration.

The term conflicted remuneration is defined as any benefit,

whether monetary or non-monetary, given to a financial services licensee (or

their representative) who provides financial product advice to persons as

retail clients that, because of the nature of the benefit or the circumstances

in which it is given:

- could

reasonably be expected to influence the choice of financial product recommended

by the licensee or representative to retail clients or

- could

reasonably be expected to influence the financial product advice given to

retail clients by the licensee or representative.[124]

However, certain benefits are exempted from the definition

of conflicted remuneration. In particular, paragraph 963B(1)(b)

of the Corporations Act provides that a benefit in relation to life

products other than a group life policy for members of a superannuation entity

or a life policy for a member of a default superannuation fund is not conflicted

remuneration. Item 8 repeals and replaces paragraph 963B(1)(b)

to limit the extent of the exemption. Proposed paragraph 963B(1)(b) provides

for a similar exemption for life insurance products outside of superannuation to

that which currently exists—subject to either the benefit ratio for the benefit

being the same for each year in which the product is continued or satisfying

the benefit ratio requirements and the clawback requirements.

Proposed paragraph 963(1)(ba) provides that benefits

in relation to consumer credit insurance are also exempt from the definition of

conflicted remuneration. Existing section 963D of the Corporations Act provides

that a benefit in relation to consumer credit insurance is not conflicted

remuneration in certain instances. The Explanatory Memorandum states that

proposed paragraph 963B(1)(b) ‘ensures that the strict arrangements that apply

to commissions paid on those products under the National Credit Code continue

to apply’.[125]

The Bill also includes a change that was not in the earlier Bill.

Proposed section 963AA specifies that the regulations may specify

instances in which a benefit given in relation to a life risk insurance product

or products is conflicted remuneration. The Explanatory

Memorandum states:

The intention of this regulation making power is to ensure

that all life insurance distribution channels are treated equally under the law

and to maintain the integrity of the reforms by providing a flexible mechanism

to address avoidance mechanisms in the future.[126]

The Minister stated that this is to ensure that ‘... sales

of life insurance that do not technically involve advice are captured by the

reforms.’[127]

Benefit

ratio requirements

Item 11 inserts proposed subsections 963B(3A)–(3C)

into the Corporations Act, to define benefit ratio and policy

cost. The benefit ratio is the ratio between the benefit (that

is, the benefit paid to an adviser or broker) and the policy cost

payable for the product for the year. The policy cost is the

total of:

- the

premiums payable for the product, or products, for that year

- any

fees payable for that year to the issuer of the product

- any

additional fees payable because the premium for the product is paid

periodically rather than in a lump sum and

- any

other amount prescribed by the regulations.[128]

The benefit ratio requirements are satisfied

in relation to a benefit for a life risk insurance product if the benefit

ratio for the benefit for the year in which the product is issued and

for each year that the product is continued is equal to or less than that

determined by ASIC, by legislative instrument, as an acceptable benefit ratio

for that year.[129]

Clawback

requirements

The clawback requirements are satisfied if:

- the

arrangement under which the benefit is payable includes an obligation to repay

all or part of the benefit if within two years after the insurance product is

first issued to a retail client either:

- the

product is cancelled or is not continued within two years after it is first

issued to a retail client, other than because a claim is made under the

insurance policy or because other prescribed circumstances exist or

- the

policy cost for the product during a year or across two years is reduced within

two years after it is first issued to a retail client and

- the

amount to be repaid under the obligation is equal to or greater than the amount

determined by ASIC, by legislative instrument to be an acceptable repayment.[130]

Although the contents of the legislative instruments are

not known, by way of guidance, ASIC’s December 2015 consultation paper proposed

the following key thresholds in relation to maximum commissions and clawback

arrangements:

- transitional

arrangements for the setting of the maximum level of commissions at 80 per

cent of the premium in the first year of the policy from July 2016, reducing to

70 per cent from 1 July 2017 and then to 60 per cent from 1 July 2018

- an

ongoing commission for policy renewals will be set at a maximum of 20 per

cent of the total of the premium paid for the renewal

- a

two-year clawback period for policies that have lapsed, with 100 per cent

of the commission repaid if the policy lapses in the first year and 60 per

cent of the commission repaid if the policy lapses in the second year.[131]

Transitional

arrangements

Item 17 inserts transitional arrangements into the Corporations

Act. Proposed section 1549A inserts the meaning of the term commencement

day. This will be 1 January 2018.

The amendments in the Bill apply to benefits given under an

arrangement that is entered into after 1 January 2018.[132]

They do not apply to benefits given under an arrangement that is entered into

before 1 January 2018—provided that the life product is issued within

three months of 1 January 2018.[133]

Further flexibility in implementation is provided through a

regulation making power to prescribe circumstances in which the arrangements

do, or do not apply.[134]

2021 Review

The success or otherwise of the proposed remuneration

arrangements is intended to be examined as part of a review by ASIC in 2021.[135]

The requirement for ASIC to undertake this review is not part of the Bill.

ASIC has existing powers under section 912C of the Corporations

Act to facilitate the collection of relevant information from financial

services licensees. Item 1 inserts new proposed paragraph 912C(1A)(e)

so that such information may be collected in a specified manner (including in

electronic form).

[1]. Parliament

of Australia, ‘Corporations

Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 homepage’,

Australian Parliament website.

[2]. Australian

Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Conflicted

remuneration, regulatory guide, 246, 4 March 2013, p. 6.

[3]. Ibid.,

p. 5.

[4]. Corporations Act

2001, paragraph 963B(1)(a).

[5]. Corporations Act

2001, paragraph 963B(1)(b).

[6]. J

Trowbridge, Interim

report on retail life insurance advice, Life Insurance and Advice

Working Group, Financial Services Council, 17 December 2014, p. 7.

[7]. Australian

Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), Life

Insurance institution-level statistics: December 2015, APRA, Sydney, 8

June 2016, p. 21.

[8].

APRA, Quarterly

life insurance performance: statistics: June 2016, APRA, Sydney, 16

August 2016, p. 8.

[9]. ASIC,

‘Life

insurance: be prepared for life’s emergencies’, MoneySmart website, last

updated 1 November 2016.

[10]. ASIC,

Review

of retail life insurance advice, report, 413, 9 October 2014,

p. 4.

[11]. Ibid.,

p. 18.

[12]. Ibid.,

p. 19.

[13]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Inquiry

into financial products and services in Australia, Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Canberra, November

2009. This inquiry is sometimes referred to as the ‘Ripoll Inquiry’ after its

chair, Bernie Ripoll.

[14]. Ibid.,

p. vii.

[15]. Corporations

Act, section 962G.

[16]. These

changes included various amendments to the Corporations Act in relation

to ASIC’s powers to make decisions to grant, suspend or cancel a licence and

bans (including amendments to sections 913B, 915C and 920A).

[17]. Corporations

Act, section 961B.

[18]. Corporations

Act, Divisions 4 and 5 of Part 7.7A.

[19]. Corporations

Act, section 961.

[20]. The

Treasury, ‘Implementation’,

Future of Financial Advice website; B Shorten (Minister for Financial Services

and Superannuation), Government’s

financial advice reforms pass the parliament, media release,

20 June 2012.

[21]. Parliament

of Australia, ‘Corporations

Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014 homepage’,

Australian Parliament website.

[22]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial

Advice) Bill 2014, p. 4.

[23]. M

Cormann (Acting Assistant Treasurer), The

way forward on financial advice laws, media release, 20 June 2014.

[24]. Corporations

Amendment (Streamlining Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014.

[25]. Australia,

Senate, Journals,

66, 2013–14, 19 November 2014, pp. 1805–1806.

[26]. Corporations

Amendment (Revising Future of Financial Advice) Regulation 2014; Corporations

Amendment (Financial Advice) Regulation 2015.

[27]. Parliament

of Australia, ‘Corporations

Amendment (Streamlining of Future of Financial Advice) Bill 2014 homepage’,

Australian Parliament website. Due to its delayed passage, the Bill as passed

was titled the Corporations

Amendment (Financial Advice Measures) Act 2016.

[28]. Supplementary

Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Streamlining of Future

Financial Advice Bill) 2014, p. 4.

[29]. Financial

Services Council (FSC), Churning

in life insurance, media release, 4 August 2011.

[30]. J

Brogden (CEO FSC), The

FSC agenda for 2012 and beyond, speech, FSC Conference 2011, 4 August

2011, p. 13.

[31]. FSC,

Churning in life insurance, op. cit.

[32]. Ibid.

[33]. Ibid.

[34]. FSC,

New

life insurance framework will reduce premiums, media release,

3 August 2012.

[35]. Ibid.,

p. 2.

[36]. K

Kachor, ‘FSC

backs down on policy framework’, Financial Observer,

15 February 2013.

[37]. Ibid.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. ASIC,

Review of retail life insurance advice, op. cit.

[40]. ASIC,

Higher

standards needed for life insurance industry, media release,

9 October 2014.

[41]. ASIC,

Annual

report 2014–15, ASIC, Sydney, October 2015, p. 37.

[42]. ASIC,

Review of retail life insurance advice, op. cit., p. 5.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. Ibid.

[45]. Ibid.

[46]. Ibid.,

pp. 7–8.

[47]. Trowbridge,

Interim report on retail life insurance advice, op. cit., pp. i–ii.

[48]. Ibid.

[49]. Ibid.,

p. 25–30.

[50]. J

Trowbridge, Review

of retail life insurance advice: final report, FSC, 26 March 2015.

[51]. Ibid.,

p. 6.

[52]. Ibid.,

pp. 6–8.

[53]. J

Frydenberg (Assistant Treasurer), Industry

reform proposal on retail life insurance welcomed, media release,

25 June 2015.

[54]. Financial

System Inquiry (FSI), Financial

System Inquiry: interim report, Treasury, Canberra, July 2014,

p. 1–20.

[55]. Ibid.,

p. 3–80.

[56]. FSI,

Financial

System Inquiry: final report, Treasury, Canberra, November 2014,

pp. 217–226.

[57]. Ibid.,

p. 219.

[58]. Ibid.,

p. 220.

[59]. Ibid.

[60]. Australian

Government, Improving

Australia's financial system: Government response to the Financial System

Inquiry, Treasury, Canberra, 2015.

[61]. Ibid.,

p. 20.

[62]. K

O’Dwyer (Assistant Treasurer), Government

announces significant improvements to life insurance industry, media

release, 6 November 2015.

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. The

Treasury, ‘Life

insurance reform legislation’, The Treasury website, 3 December 2015.

[65]. K

O’Dwyer, ‘Second

reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’ (earlier Bill), House of Representatives, Debates,

11 February 2016, p. 1368.

[66]. ASIC,

ASIC

consults on implementation of retail life insurance advice reforms,

media release, 15 December 2015.

[67]. Ibid.

[68]. ASIC,

Retail

life insurance advice reforms, consultation paper, 245, ASIC, 15 December

2015, pp. 14–18.

[69]. An

‘approved product list’ generally refers to information about certain financial

products put together by advice businesses to give their advisers the authority

to provide advice about those products (ASIC, ‘Financial

products and sales incentives: checking limits and connections’, Moneysmart

website, last updated 9 November 2016).

[70]. O’Dwyer,

Government announces significant improvements to life insurance industry,

op. cit.

[71]. Australian

Government, Improving Australia’s financial system: Government response to

the Financial System Inquiry, op. cit., p. 21.

[72]. R

Fogarty, ‘Who’s

who in the Commonwealth Bank’s life insurance scandal’, Australian

Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) News, 8 March 2016.

[73]. S

Ferguson, K Toft and M Christodoulou, ‘Money

for nothing’, Four Corners, ABC, 7 March 2016.

[74]. ASIC,

Update

on ASIC’s investigation into CommInsure, media release, 12 October

2016.

[75]. ASIC,

Life

insurance claims: an industry review, report, 498, ASIC, October 2016,

p. 22.

[76]. ASIC,

Update on ASIC’s investigation into CommInsure, op. cit.

[77]. ASIC,

Life insurance claims: an industry review, op. cit.

[78]. Ibid.,

p. 4.

[79]. Ibid.,

p. 6.

[80]. Ibid.,

pp. 10–11.

[81]. FSC,

Life

insurance code of practice, media release, 11 October 2016; O’Dwyer, Government

announces significant improvements to life insurance industry, op. cit.

[82]. FSC,

Life

insurance code of practice, FSC, [Sydney], 2016, pp. 2, 24.

[83]. Ibid.,

p. 26.

[84]. Parliamentary

Joint Standing Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, ‘Inquiry

into the life insurance industry’, Inquiry homepage.

[85]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Corporations

Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 [Provisions],

The Senate, Canberra, 2016. Details of the terms of reference, submissions to

the Senate Standing Committee on Economics and the final report are available

on the inquiry homepage.

[86]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 [Provisions], op. cit., p. 1.

[87]. Austbrokers

Financial Solutions (SYD), Submission,

no. 4, to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics Legislation, Inquiry

into the Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill

2016, 2016.

[88]. K

Davidson, Submission,

no. 17, to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics Legislation, Inquiry

into the Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill

2016, 2016.

[89]. P

Harrison, Submission,

no. 24, to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics Legislation, Inquiry

into the Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill

2016, 2016.

[90]. B

Moss, Submission,

no. 25, to the Senate Standing Committee on Economics Legislation, Inquiry

into the Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill

2016, 2016.

[91]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 [Provisions], op. cit., p. 24.

[92]. Ibid.,

p. 25.

[93]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Alert

digest, 2, 2016, The Senate, 24 February 2016, p. 63.

[94]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at pages 23 and 24 of

the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill.

[95]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Thirty-fourth

report of the 44th Parliament, 23 February 2016, p. 1.

[96]. J

Chalmers, ‘Second

reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’, House of Representatives, Debates,

3 March 2016, p. 2982.

[97]. Ibid.

[98]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016 [Provisions], op. cit., p. 25.

[99]. O’Dwyer,

‘Second reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’, op. cit., p. 1398. K O’Dwyer (Minister for

Revenue and Financial Services), ‘Second

reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’ (current Bill), House of Representatives, Debates,

12 October 2016, p. 10.

[100]. Association

of Financial Advisers, Life

Insurance Framework improvements achieved, media release, 6 November

2015.

[101]. FSC,

FSC

statement on life insurance reforms, media release, 6 November

2015.

[102]. FSC,

Life

insurance remuneration reforms, media release, 12 October 2016.

[103]. Financial

Planners Association (FPA), FPA

welcomes “fair and workable” government announcement on life insurance,

media release, 9 November 2015.

[104]. Ibid.

[105]. National

Seniors Australia, Submission

to Treasury, Inquiry into Life insurance reform legislation,

4 January 2016, p. 1.

[106]. Ibid.,

p. 2.

[107]. Choice,

Life

insurance reforms a good first step: further reforms needed before consumers

can trust advice is in their interests, media release, 6 November

2015.

[108]. Ibid.

[109]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016, p. 4.

[110]. Ibid.,

pp. 19–20.

[111]. K

Swoboda, Corporations

Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016, Bills

digest, 103, 2015–16, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 31 March 2016, pp. 1,

17. Parliament of Australia, ‘Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance

Remuneration Arrangements) Bill 2016’, op. cit., clause 2.

[112]. O’Dwyer,

‘Second reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’, op. cit., pp. 10–11.

[113]. Corporations

Regulations 2001, subregulation 7.7A.16C(2). Subregulation 7.7A.16C(3)

specifies that where an enterprise agreement has not expired by 1 July 2013,

then the grandfathering applies for 18 months after the nominal expiry date.

The Corporations

Act 2001, paragraph 1528(4) specifies that the ban on conflicted

remuneration applies from 1 July 2013, unless an earlier date applies. A

nominal expiry date must be no longer than four years from the date the Fair

Work Commission approves the agreement (Fair Work Ombudsman, ‘Enterprise

bargaining’, Fair Work Ombudsman website).

[114]. O’Dwyer,

‘Second reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’ (earlier Bill), op. cit.; O’Dwyer, ‘Second reading

speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements) Bill

2016’ (current Bill), op. cit.

[115]. Trowbridge,

Interim report on retail life insurance advice, op. cit., p. 7.

[116]. H

Gravelle, ‘Remunerating

information providers: commissions versus fees in life insurance’, Journal

of Risk and Insurance, 61(3), September 1994, p. 425.

[117]. Ibid.,

p. 452–453.

[118]. Financial

System Inquiry, Final report, op. cit., pp. 220; Trowbridge, Review

of retail life insurance advice: final report, op. cit., p. 6.

[119]. G

Pearson, ‘The

place of codes of conduct in regulating financial services’, Griffith

Law Review, 15(2), 2006, pp. 340–342.

[120]. Ibid.,

p. 363.

[121]. N

Howell, ‘Revisiting

the Australian Code of Banking Practice: is self-regulation still relevant for

improving consumer protection standards?’, University of New South Wales

Law Journal, 38(2), 2015, p. 552.

[122]. Trowbridge,

Review of retail life insurance advice: final report, op. cit.,

p. 11.

[123]. Financial

System Inquiry, Final report, op. cit., p. 220.

[124]. Corporations

Act, section 963A.

[125]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016, p. 9. The National Credit Code is at Schedule 1

to the National

Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009.

[126]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements)

Bill 2016, op. cit., pp. 8–9.

[127]. O’Dwyer,

‘Second reading speech: Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration

Arrangements) Bill 2016’ (current Bill), op. cit.

[128]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsection 963B(3B).

[129]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsections 963BA(1) and (2) inserted by item 13

of the Bill.

[130]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsections 963BA(3) and (4) inserted by item 13

of the Bill.

[131]. ASIC,

Retail life insurance advice reforms, op. cit., pp. 14–18.

[132]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsection 1549B(1) inserted by item 17 of the

Bill.

[133]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsection 1549B(2) inserted by item 17 of the

Bill.

[134]. Corporations

Act, proposed subsection 1549B(3) inserted by item 17 of the

Bill.

[135]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Corporations Amendment (Life Insurance Remuneration Arrangements)

Bill 2016, op. cit., p. 12.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.