Papers on Parliament No. 32

December 1998

Prev | Contents | Next

At a little past 8:00 pm, on the evening of 18 November 1896, Colonel George William Bell addressed the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention on the theme, ‘Progressive Liberty’.[1] The School of Arts hall was crowded to capacity as the 200 official delegates were joined by Bathurst townsfolk, who in spite of a drenching summer storm, had turned out in strength to hear the Colonel’s lecture. The audience overflowed from the public galleries down to the floor of the hall behind the delegates.

Colonel Bell, as he was popularly known in the colony, was the Sydney-based Consul for the United States of America, that nation’s chief representative in New South Wales. Bell was also a highly regarded public speaker, billed as ‘The Silver Tongued Orator of the Pacific’.

There was some debate, or discussion at least, earlier that afternoon about interrupting the work of the Convention for Bell’s lecture.[2] The decision to break to hear Colonel Bell was virtually unanimous, such was the high regard of the delegates for their visiting speaker. At 9:45 pm, at the conclusion of his speech, delegates resumed their constitutional deliberations. Clearly, Colonel Bell was someone thought worthy of the interruption of proceedings and the inconvenience of a very late sitting.

The American consul’s presence at the Bathurst Convention provides something of a mystery or a puzzle. Perhaps, it would be better to speak of three puzzles, each connected with the other. First, who was this Colonel Bell? Beyond being the American consul and a celebrity speaker, what do we know of this man? More importantly, what did the Bathurst organisers know about him? The enquiries of this writer about the identity of Colonel Bell remain incomplete. No doubt with more research further facts will be uncovered, but identifying Bell is not simply a question of more research and more facts. An appropriate metaphor to use in describing Colonel Bell might be that of the onion, an object composed layer upon layer. There was, as we shall see, more than one layer to the Colonel. On the surface, he was by all accounts a man of charm and bonhomie. His activities as Consul, however, suggest an unexpected shrewdness, even slyness, lying beneath the outer layer of geniality.

While this writer confesses a liking for the gentleman, there is also a suspicion that Colonel Bell had a touch of the ‘flim flam man’, or confidence man, about him. But I must disclose a cultural bias, that of the Canadian always on guard against the smooth-talking Sam Slick from south of the border.[3] There is an air of the Sam Slick about this Colonel Bell.

The second area of enquiry is to ask why Bell, a foreign official, was invited to attend and address a gathering so purposely Australian as the Bathurst Convention. For dignitaries to present a speech to the Convention was not in itself unusual. Several leading individuals of the day addressed the Bathurst Convention, including Cardinal Moran and premier George Reid. But Colonel Bell was the only foreigner invited to do so. Indeed, it appears that this was the only occasion when a representative of a foreign nation addressed a major federation convention or conference. Colonel Bell’s address is, then, an unique event in the history of Australian federation.

The third question is to ask what influence might his presence in Bathurst have had on the Convention and its deliberations. To extend the question, did Colonel Bell have any influence in the shaping of our federation arrangements? What were his views on the proposed federation? Was he friend or foe? Some answers to these questions will be provided. The word, ‘some’, is a necessary qualification because the Colonel is an enigmatic character. It would be unfair to describe him as ‘untruthful’ or ‘duplicitous’ but his public utterances, always positive, are sometimes unlike the frank assessments provided in his despatches to the US State Department.[4] Perhaps this is more a measure of his skill as a diplomat than of dishonesty of character. On the surface, he presented himself as a good friend of federation; in his despatches, however, he expressed doubts that the shape it was taking would be in his country’s best interests.

Who was Colonel Bell?

This question is not answered with confidence. The researcher today soon discovers that most of what was publicly known about the Colonel at the time of the Bathurst Convention can be traced back to what Bell himself cared to reveal. A few carefully placed press articles provided his life story.[5] Whenever biographical information was called for, the press of the day recycled these accounts.

According to these sources, George Bell was born around 1840 in Virginia, and spent most of his adult life in the northern states. During the American Civil War it was stated that he served for three years in an Illinois (northern) regiment, ‘Yates’ Sharpshooters’.[6] The local assumption was that his Civil War service was the source of his becoming a colonel. However, the records of that regiment indicate that the highest rank Bell held was that of 2nd Lieutenant.[7] It is possible that Bell’s rank of colonel was an honorary rank bestowed on him by a state legislature, similar to that held by another famous American, from Kentucky. Whatever the source or authenticity of his rank, Colonel Bell encouraged its use by friends and the public. He did not, though, as a general practice at least, use this title in his consular correspondence with the State Department. The general unawareness of his given names, George William, was such that when he died in 1907, his obituary writer named him as George Washington Bell. The name perhaps reflects as well the degree to which Bell had come to personify America for Australians.

After the Civil War, Bell claimed to have earned his living as a lawyer and to have served in public office, but the details are vague. His residence in the United States prior to taking up the position of US Consul was in the state of Washington, in the logging and fishing town of South Bend. Information supplied by South Bend’s museum shows that Bell came to South Bend from Indiana, during the early days of South Bend’s land boom of the 1880s, to engage in real estate.[8] It is easy to imagine Bell as a land ‘boomer’. He left his children behind in South Bend when he came to Sydney. He never revealed anything publicly about his family or his relationship with them. One wonders though why they were not with him in Sydney. He took leave on at least two occasions to visit his family and to attend to family affairs.[9] The brevity of the visits, however, and his lengthy periods of separation in Australia do not suggest a happy domestic life.

Bell was not a career diplomat; he had no previous diplomatic experience. An active Democrat, he campaigned in 1893 for the election of Grover Cleveland for president and was rewarded with the appointment in Sydney. His appointment was terminated with little warning in 1900 during the presidency of William McKinley, a Republican.[10] Initially, Bell managed to hold onto his position with the change of parties in 1897. His dismissal, when it did come, took him by surprise. The loss of his consular position was a serious blow.

For reasons that are not explained, Colonel Bell preferred not to return to his beloved America following his dismissal from the consular service.[11] Instead, he elected to remain in Australia after a short visit to England. Around this time, he took an Australian wife, presumably his American wife by then being either dead or divorced. He tried his hand at several business ventures on retirement; none appear to have been especially successful. One venture, the manufacturing of weighing scales, brought claims of patent infringement by an American company, Computing Scales Co. of Dayton, Ohio.[12] All information suggests Bell was not a man of wealth.[13] One of his main sources of income on retirement from the consular service appears to have been as a public speaker. The rising importance of China and Japan to Australia was a popular topic.

With separation from family and possible self-imposed exile from America, Bell’s bare bones of a biography whisper mystery, perhaps even personal tragedy and inner unhappiness. Yet all published accounts show Bell to have been an accomplished public man, a gentleman of back-slapping bonhomie with boundless enthusiasm for whatever interested his hosts and constant praise for Australian achievements. To quote one of his admirers, ‘He had the qualities which everywhere command attention¾good sense, keen perception, extensive knowledge, great industry, devotion to duty, and polished manners. In him Americans soon felt they had a “friend at Court”, and Australians felt complimented by his being sent amongst them to represent “the Great Republic.”’[14][1]

One or two similar quotes from the many press and journal accounts of the popularity of the Colonel will provide a glimpse of Bell’s reception in colonial society. The 31 December 1895 issue of Cosmos Magazine devoted an entire article to the Colonel, noting that after only two years residence, the American Consul ‘ ¼ has so identified himself with our interests that he is no longer a stranger in our midst, but an ever-welcome guest at every notable gathering of citizens.¼ ’[15] The article concluded: ‘ ¼ among those who have taken up a temporary abode in our midst none has been more indefatigable in our service than the esteemed Consul of the United States.’ The Storekeeper, a Sydney commercial paper, claimed that Bell had won for himself ‘a position both commanding and unique’ in the eastern colonies.[16][1]

In appearance, Bell was described¾on the occasion of his Bathurst lecture¾as ‘a stalwart, fine-looking elderly man’.[17] The photograph accompanying the 1895 Cosmos article shows a slightly built gentleman of thoughtful but amiable countenance.[18] He sports an oversize, bushy moustache below a beaky nose and shows a hairline that has receded to all but a token remnant; his head thrusts turtle-like from the carapace of his evening dress. Overall, his appearance elicits sympathy and trust.

One of his best friends in the colony was George Reid, the premier of New South Wales, in whose company Bell attended many colonial social gatherings. One can imagine these two gentlemen, Laurel and Hardy in their appearance, working the crowd, a joke here and a word of wisdom there, handshakes and back slaps everywhere. And, always telling their listeners what they wanted to hear.

Colonel Bell as American Consul

Another layer of Bell’s character is revealed in his consular activities.[19] At times he could act foolishly, but always from motives of patriotism. He took his position as America’s representative very seriously. Advancing and defending America’s interests in the colony was for Bell a work of total commitment. In this work, his public bonhomie, like the cloak of the thriller spy, disguised a measure of slyness and cunning.

A certain cunning can be seen in his handling of Independence Day activities.[1] During Bell’s term, the traditional open house at the American consulate in Sydney became a dry affair. This seems quite out of character for the ebullient, jolly Bell, but he was indeed a teetotaller in his personal habits. He happily attended functions where alcohol was served, even dinners held in his honour. But in the case of the 4 July open house, he broke with the well-established custom by not providing free alcohol and cigars to the well-wishers of the day. His argument was that only those who were genuine in their feelings would now attend the consulate on Independence Day rather than those who came only for the free grog and smokes. This decision may also reflect his understanding of Australian character. The event was still well attended, as Bell was able to prove with the press clippings accompanying his reports home. The names in the guest books, America’s true friends in the colony, were kept on file, a list of friends to be cultivated.

Bell worked to ensure his country’s strategic interests in the Pacific.[20] Concerned that Admiral Dewey’s fleet operating off the Philippines might encounter coaling problems, Bell secretly¾and on his own authority¾instructed the Newcastle Vice-Consul to secure coal supplies for the American fleet at Newcastle, the colony’s main coal supply port. The Vice-Consul advised an unknowing State Department of his progress in this task with the result that Colonel Bell was ordered to explain his actions to Washington and was duly chastised for this unwanted initiative.

The 1898 Spanish-American War offered Bell one of his greatest challenges as propagandist for America.[21] The war against Catholic Spain brought public criticism of America from Cardinal Moran, who unreservedly cautioned the Australian public against American jingoism and imperialism. Cardinal Moran warned of unbridled American expansion. In his view even the invasion of Canada and war with Britain was possible. This was a difficult time for Bell, who not only wished not to jeopardise his personal friendship with the Cardinal, but had to defend American policy without slandering the clergyman. The Cardinal’s words risked the undoing of Bell’s hard work in presenting America as the benign friend of the Australian colonies. Bell acquitted himself with alacrity in this task. Popular support for American policy continued undiminished, as did Bell’s public friendship with the Cardinal. At the Consulate’s Independence Day gathering that year, his good friend, premier George Reid, publicly expressed ‘the most sincere wishes for an early success in the present unfortunate conflict with Spain.’[22]

As Consul, Colonel Bell mixed with the most powerful and influential of the colony’s citizenry. He was generally well-liked and had the trust of many. The most graphic, and alarming, example of Bell’s ability to gain confidence is perhaps the case of Major General Sir George French, commandant of the colony’s defence forces.[23] An expert in coastal artillery, French had developed certain improvements for concentrating the fire of coastal batteries already adopted by the British but which he wanted to patent in the United States under his own name. Bell wrote:

as he is a personal friend I prevailed upon him to submit his specifications to my government, impressing upon him my opinion that his interests as an inventor would not be prejudiced by such action. Sharing the general sympathy of Australia to our cause at present (the Spanish war), he enthusiastically accepted my suggestion and placed the documents in my hands.

The documents may have included maps, charts and specifications relating to the colony’s coastal defences.

A reading of Bell’s consular reports suggest eccentric, even quixotic behaviour but also a practical intelligence and an amazing ability to convince and gain the trust not only of individuals but of whole sections of society. The motive for Bell’s actions, however, was consistent. What he did was always, in his view at least, for the benefit of American interests in Australia.[24] Foremost of those American interests were matters of commerce and trade. Bell worked assiduously to advance American trade with Australia, promoting American products and trade links and cultivating relationships with colonial politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen. Bell’s opinion, expressed within months of his arrival, was that Australia was ‘a fine field for American enterprise¾if properly cultivated’.[25] This was the man invited to the Bathurst Convention—Colonel Bell: the well-regarded American Consul, popular member of Sydney society and good friend of Premier Reid, and a leading public speaker of the day.[26] The Colonel was a celebrity of his times. Below the bon-vivant surface, however, there was Bell the tireless worker for American interests in Australia.

The Bathurst Invitation

Dr George Hurst, a Bathurst medical practitioner and member of the Convention’s General Committee, suggested the invitation of Colonel Bell to the Convention.[27] This was made at the meeting on the 22 October 1896. Colonel Bell was to be invited to deliver a lecture on the American Civil War on the Thursday evening of the Convention: ‘It was resolved that the matter of illustrating the lecture with slides or delivering it without descriptive pictures be left to the Colonel to decide.’ It was also decided separately at the same meeting that Bell would be invited to attend the Convention as a ‘guest’, the same invitational status given Cardinal Moran and other non-delegate participants.[28]

The invitation for Bell to speak, changed to the Wednesday (18 November) evening and to be ‘with or without lime light illustrations’, was sent out on 31 October by William Astley, the organising secretary.[29] This gave Colonel Bell less than three weeks notice. Astley apologised for the short notice of the request, ‘shorter indeed than it should have been owing to a clerical error’. On the proposed topic, ‘The American Civil War’, Astley wrote:

The distinction, Sir, which you have readily earned as a lecturer and the familiarity with the suggested theme, which you must necessarily have both as a student and as a man who bore his part in the great conflict, have suggested to the Committee that the conjunction of time, and place, and lecturer, would be particularly interesting and noteworthy.

The suggestion of this particular topic, so out of place for a convention on federal unity, may have been out of consideration for the little time available to Bell to prepare a talk, especially given that he had just returned from furlough in America. A follow-up letter a few days later advised the Colonel of the availability for his lecture of the excellent lantern slide collection¾‘the finest in the colony’¾at St Stanislaus College. It seems from the organising committee’s minutes that Colonel Bell was the only outside speaker considered for the Convention. As a well-known speaker of the day, his presence would certainly attract interest especially among country delegates who may otherwise never have had a chance to hear him. Registrations were lagging at the time of the suggestion of a lecture by Bell and this may have had some bearing on his inclusion in the program.

There was also some anxiety in the early days of planning the Convention that the discussion of the draft constitution would not sufficiently occupy the time of the delegates. Diversions and entertainments must be provided, or so it was thought. As well as arrangements for impromptu activities, such as shooting matches between Bathurst marksmen and the visitors, a social program of organised activities at arranged times through the week was drawn up. Monday would see an inaugural public meeting. Lectures were planned for Tuesday and Thursday evenings. The illumination of Machattie Park was set down for Wednesday and a garden party, hosted by the Ladies’ Committee, was planned for Friday afternoon. The intended lecturer for Tuesday was to have been Father Dowling, a local Catholic priest and keeper of the impressive lantern slide collection at St Stanislaus’ College. However, it was soon discovered that the rules of his order prevented him from speaking at a political gathering.

As it turned out, Father Dowling’s lecture time, along with much of the time set aside for socialising, was needed for the business of the Convention. To quote the Sydney Mail:

It was at first thought that to attract delegates to Bathurst, side-shows in the way of entertainments and lectures and so forth would be necessary to make the thing go; so garden parties, entertainments, and public meetings and lectures were arranged for, which in the end were superfluities as the delegates showed desire to stick to the convention, in spite of all the charms that might be offered them outside.[30]

The Convention resumed for evening sessions on all five available evenings (Monday to Friday). The Monday evening took the form of the planned public meeting, but was little more than a series of speeches by key delegates; the Wednesday evening session was preceded by Colonel Bell’s speech. The Machattie Park illuminations took place, postponed a day by rain, but now more for the amusement of Bathurstians than their guests, who were busy at their discussions two blocks away. The Ladies’ Committee garden party also went ahead on the Friday afternoon, but doubled as a dinner break between afternoon and evening sessions. It would have been a brave but foolish man who would have suggested its cancellation.

Colonel Bell, too, shared this view of dispensing with superfluities and entertainments. The organisers may have initially regarded his lecture as only an entertainment but this was never Bell’s view. Bell immediately responded to Astley’s invitation, expressing his willingness to come to Bathurst but not to speak on the subject of the Civil War. Bell’s letter is not available, but its contents are reflected in Astley’s reply of 4 November:

I appreciate the nature of the considerations which precluded your acceptance of our request. It is with great regret that I now recognise that our application must have revived very sad memories.

I have not had time to communicate with the Committee, as to your kind offer to give a lecture on the ‘American Union’, but by the direction of the President (Dr Machattie), I have now to intimate that we shall be grateful if you can favour us with a lecture on ‘The American Union; its constitution and practical working’. With the characteristic touches of vivacity that you could impart, we are satisfied that such a lecture from you would be most interesting and instructive.[31]

All was agreed. Bell would address the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention on the evening of 18 November on the subject of American politics and government.

A few days before that engagement, on 13 November, further public evidence was given of Bell’s high standing in the colony.[32] To welcome him back from his furlough in the United States, a banquet was got up at the Town Hall in Sydney. As recorded in the testimonial booklet prepared for the event, ‘95 persons of high ranking in the political, business and professional spheres sat down to welcome in true British style their honoured guest, the gifted and popular Consul for the United States.’ The guests included George Reid and Sir George Dibbs, along with other members of government and opposition, as well as many well-known members of the business community, including Quong Tart. Several names on the banquet list are also to be found on the Bathurst Convention delegate and guest list. (This possibly included Edmund Barton for there is an ‘Edward’ Barton, QC, on the banquet list.)

Colonel Bell’s Lecture at Bathurst

According to the Proceedings of the Bathurst Convention, in the evening session of the third day of the Convention, Colonel Bell delivered an address on ‘Progressive Liberty’. This was not the title or subject promised two weeks earlier. The subject was to have been the American political system, specifically the workings of the American Constitution. Bell touched on this theme but he did not offer a detailed discussion on the American political system as originally promised. The reason for altering his lecture topic may have to do with what the Convention had been discussing the previous day¾a directly elected Governor-General. The debate on an elected Governor-General had been initiated by one of the few republicans at the Convention, John Norton, and inevitably led to a comparison of the relative merits of the British parliamentary and American republican systems. Echoes of republicanism continued with the debate that followed on a directly elected Senate. Bell would not have wished to be drawn into these discussions or to be seen to be offering partisan advice (which could happen if he offered a too detailed and glowing account of America’s republican system of government).

It is possible that the change in topic occurred before the Norton republican debate but the same explanation of Bell not wanting to be drawn into an open contest between the two systems holds. When Bell accepted the invitation he had only just returned from two months in America. He may not have initially appreciated the nature of the Convention, especially if he had relied on the advice of friends such as George Reid. By mid-week, many initially dismissive of the Convention, including George Reid, were rethinking their positions.

What words of wisdom¾noncontroversial and soothing for sure¾did Colonel Bell offer his Bathurst audience? The speech, reported in detail in all three of Bathurst’s daily newspapers, was standard Bell fare, if a little more rambling than usual.[33] Some portions are clearly from an earlier speech, delivered in July. He began by praising the work of the Convention and its connections with the ‘priceless heritage’ of liberty shared by Americans and Australians/Britons. After praising the place of liberty within the ‘British nation’ he shifted into a discussion of the advantages of increased trade between America and Australia. Bell informed his audience:

The people of Australia are the greatest commercial race in the world. Per capita they sold and bought more than any other nation on the face of the globe. (Applause) The four millions of people in Australia were as good in commercial dealings as 20,000,000 Americans. The people in this country didn’t realise the true and important position they occupied in the commercial world.[34]

After making a comparison between Russia and Australia that favoured Australia as the nation both wealthier and more liberal, Bell spoke favourably of federation, which would lay ‘the foundation stone of a grand future and mighty nation than was ever dreamt of. (Hear, hear)’. In comparing Australia’s incipient nationhood with America’s revolution, for Bell the difference was that the American people were British subjects, fellow Anglo-Saxons, forced to take up arms to regain their British liberty. He admitted his own republicanism, but ‘pointed out that Great Britain, with its different system, was as free as any people on the face of the earth.’ After a rambling discussion on American government and politics¾during which he corrected some misunderstandings reported to him at the Convention, but offered nothing that would challenge the status quo sentiments of the Convention¾Bell closed his address with final words of support for the union of the Australian colonies and the ‘great advantages that must necessarily follow in the wake of Federation.’

Fulsome praise for Australia and its political aspirations, homage to British culture and a reminder of the Anglo-Saxon kinship of Australians and Americans are clearly presented in Bell’s speech, along with promises of wealth-creating advantages to Australians with improved American-Australian trading relations. He does not elaborate on the ‘great advantages’ that will follow federation. There is no need. In the minds of his listeners, his answer has already been planted.

The speech was well received. Appreciative laughter, applause and shouts of ‘Hear, Hear’ accompanied the speaker throughout and he resumed his seat ‘amidst rapturous applause’. Only one rude interjection was reported, from Mr John Norton, given as Bell began his concluding remarks by offering an apology for having imposed on the time of his listeners. Bell’s response to Norton’s interjection, that ‘there were some people who, no doubt, would like to have him [Bell] squelched altogether; men whose mouths were so near their ears that they loved to listen to their own voices at every possible moment’, was greeted with ‘uproarious laughter and loud applause’. Bell obviously knew John Norton.

He Came, He Spoke, But Did He Conquer?

What influence did Colonel Bell and his speech have on the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention of 1896?[35] In the sense of influencing the course of discussions and decisions it is difficult to see any impact. As already suggested, his presence did nothing to advance the cause of republicanism. But, equally, the defeat at Bathurst of Norton’s republican efforts certainly did not require any assistance from the Colonel. The delegates, many of whom were men of commerce, would have appreciated his remarks on the wealth that would come with the improved economic arrangements of federation. However, no matter Bell’s presence, the decisions they made at the Bathurst Convention would have been the same.

Nonetheless, Colonel Bell’s presence at Bathurst was important. He was a celebrity of his time, the representative of the great and powerful American Republic. Many Australians aspired for their new country to be in many respects not unlike the United States, once a cluster of colonies and now a successful, populous nation. Bell’s presence, his words of support for federation, his assurances that the Australian colonies were on the correct path, could only contribute to the confidence of delegates to continue with the task of nation building.

It is quite impossible to prove any of this, of course. We have only the newspaper reports to guide us in assessing the impact of Bell’s speech on his audience. They suggest his audience went home, or back to the business of the convention, largely pleased with what they had heard from their American guest speaker. Onward to federation!

To extend the question to his possible influence on federation generally, we come up with much the same answer. His writings and speeches, his very interest, contributed to the chorus of pro-federation sentiment but it is a challenge to claim anything more on his behalf. His attempt to steer the Australians away from preferential treatment for British trade was ultimately unsuccessful. Following the example of the other British dominions, Australia adopted a trade preference policy for British goods in 1907.[36] Bell’s chances to achieve otherwise were probably never that strong, such were the pro-British sentiments of the Australians. These sentiments swept away all other considerations and possibilities. Although his audiences cheered his suggestion of a closer relationship with America, Bell saw for himself how they rallied without hesitation to Britain’s call in South Africa.

Although careful never to comment or advise directly, Bell did provide information on the American system through gifts of books, to the New South Wales Parliamentary Library for example. Books on government and constitutional subjects were also regularly lent from the consulate’s own small library to politicians and public servants. In 1897, he reported home that:

.... with the Federal Movement now fairly inaugurated there are more inquiries into the workings of our political system than ever before, and I have endeavoured to furnish such information as required by those giving form to the new order of things.[37]

Bell does not reveal who was calling at his consulate for such information. Further research just might reveal something of interest.

What did Bell really think of Australians? Were his private thoughts the same as his public pronouncements of praise? The lack of private papers makes this question difficult to answer, but his consular reports contain confidential comments not meant for Australian eyes.[38] He found the average Australian politically apathetic, and alarmingly so. Australian businessmen he thought to be overly conservative and lacking in entrepreneurial drive. There was too much involvement by government in the affairs of business. The ties with Britain were too strong. However, Bell had many positive comments to make, especially in the context of the environment of social equality and justice that he found to exist in Australia. His public statements about Australia and its people do seem to be based on an honest, if slightly qualified, private assessment. It was a place almost like home.

Because Colonel Bell’s appointment ceased in August 1900, we do not have the advantage of his consular reports for the last months of the processes of federation and the birth of the Commonwealth of Australia. His successor, Orlando Baker from Iowa, did not share Bell’s interest in the subject. His reports are less detailed, less informative.[39] Orlando Baker had other worries, mind you. The consulate had lost its one and only typewriter and the paper work of the consulate had ground to a halt. Claimed as private property, the machine had been spirited away by Colonel Bell on his departure.[40]

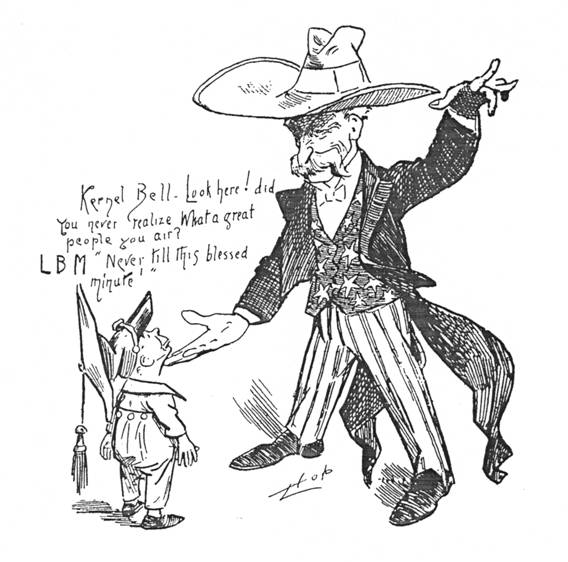

This cartoon was published in The Bulletin at the time of the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention, November 1896. Colonel Bell, as Uncle Sam, offers praise to the Australian people; LBM (Little Boy from Manly) responds. Hop the cartoonist was an American.

[1] Proceedings, People’s Federal Convention, Bathurst, November, 1896, Sydney, Gordon & Gotch, 1897, p.25.

[2] The day’s proceedings are well documented in the Bathurst newspapers of the following day. For example, see the National Advocate, 19 November 1896.

[3] Sam Slick was a smooth-talking Yankee pedlar in a series by the Canadian author, T.H. Halliburton (1796-1865). The person and character of King O’Malley, the populist politician, may provide a more familiar example of the type for Australian readers.

[4] Microfilm G273, G274 and G275. Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State. Despatches from United States Consuls in Sydney, NSW, 1893-1906. (National Archives, Washington). For sake of brevity, this material will be referred to by the microfilm reel (held by the National Library of Australia).

[5] For example, an American-published article available in Australia, ‘The Consular Service under Cleveland,’ The Illustrated American (9 November 1895), p. 610, provided a brief biography for Bell. This information was repeated in the Australian press, for example, ‘A Popular Consul,’ The Storekeeper, 13 February 1896, p. 20. Other biographical fragments have been gleaned from other sources cited in this paper.

[6] This unit is the 64th Illinois Infantry Regiment. A search of the Illinois State Archives’ Database of Illinois Civil War Veterans (URL http://www.sos.state.il.us/depts/archives/datcivil.html) shows a George W. Bell serving in this unit. Rank not given. Hometown is given as Princeton, Illinois.

[7] Information provided by Susan Potts of the Illinois Civil War Project (URL http://www.rootsweb.com/~ilcivw) from off-line sources. Susan’s sources show George W. Bell enlisting in B Company of the 64th as a private on 1 November 1861; promoted to 1st Lieut. on 3 June 1862 and 2nd Lt. on 8 August 1862. He resigned from the army on 21 July 1864 with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. According to South Bend newspaper sources (see footnote 8), in that community in the early 1890s, Bell was known as ‘Captain’ Bell. Thus, his colonelcy appears only with his arrival in Australia.

[8] Information from local newspapers provided by Bruce Weilepp, Museum Director, Pacific County Historical Society, South Bend, WA, USA. The scale¾and success¾of Bell’s real estate and property development activities are not known. The South Bend Journal, 2 December 1892 discusses Bell’s efforts to induce eastern firms to locate major operations in the town, including a brewery, a gas plant and woollen mills. His efforts appear to be more verbal than fiscal. See R.C. Bailey, ‘South Bend, Washington¾Baltimore of the Pacific’, The Sou’wester, Autumn 1994, pp. 3–18 for a brief history of the South Bend boom.

[9] G274 Consular Report (6 June 1899).

[10] G275 Consular Report (29 and 31 August 1900).

[11] ‘Death of Colonel Bell’ in Mitchell Library Newspaper Cuttings. Volume 153, p. 192. (1906-8).

[12] G275 Consular Report (24 January 1901).

[13] G275 Consular Report (31 August 1900).

[14] Report of the Proceedings at the Banquet to Col. Geo W. Bell, Sydney, 1896, p. 1.

[15] ‘Colonel Geo. W. Bell,’ The Cosmos Magazine, 31 December 1895, pp. 154–158.

[16] ‘A Popular Consul,’ The Storekeeper, 13 February 1896, p. 20.

[17] ‘Lecture by Colonel Bell’, Bathurst Free Press, 19 November 1896.

[18] Photograph by Kerry & Co, The Cosmos Magazine, 31 December 1895, p. 155. The photograph must have been a favourite of Bell’s for it appears in many publications.

[19] G274 Consular Report (16 July 1898).

[20] G274 Consular Report (21 May 1898).

[21] G274 Consular Report (5 May 1898).

[22] G274 Consular Report (16 July 1898).

[23] G274 Consular Report (7 May 1898).

[24] G274 Consular Report (13 March 1896).

[25] G273 Consular Report (16 May 1894).

[26] Some published speeches: ‘Anglo-Saxon Unity,’ The Storekeeper, 19 July 1894; ‘The Evolution of Commerce,’ The Storekeeper 2 July 1896.

[27] Minutes of the General Committee of the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention (22 October 1896), Mitchell Library MSS 269/2-3; 6-7 (mfm CY312).

[28] ‘Invited Guest’ and ‘Invited Member’ seem to be used indiscriminately in the published proceedings of the Convention. Colonel Bell and Edmund Barton are both described as ‘invited members’; Cardinal Moran is an ‘invited guest’.

[29] Letterbook (William Astley) of the Bathurst People’s Federal Convention (October-November 1896), Mitchell Library MSS 269/1 (mfm CY3129).

[30] Sydney Mail, 28 November 1896.

[31] Letterbook, Mitchell Library MSS 269/1 (mfm CY3129).

[32] Report of the Proceedings at the Banquet to Col. Geo W. Bell, Sydney, 1896.

[33] National Advocate (Bathurst), Bathurst Daily Times and Bathurst Free Press, 19 November 1896. The articles in the Daily Times and the Free Press are identical.

[34] National Advocate (Bathurst), 19 November 1896.

[35] There is no report in Bell’s consular files of his trip to Bathurst or of his speech. As he did send home reports on similar activities, it is possible that the Bathurst report is simply missing.

[36] R.S. Russell, Imperial Preference, 1947, p.17.

[37] G274 Consular Report (22 March 1897).

[38] G275 Consular Report ‘A Glimpse of New South Wales’ (30 October 1899). This is a 16-page ‘intelligence’ report on the economic, political and social situation in the colony. It contains many interesting observations.

[39] G275 Consular Report (February 1901). In this report, Baker titles Prime Minister Barton as Premier General Barton.

[40] G275 Consular Report (10 September 1900).

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top