Introduction

Referral of the inquiry

1.1

On 20 June 2018 the Senate referred the following matters to the Senate

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee (committee) for

inquiry and report by 30 August 2018:

Possible regulatory approaches to

ensure the safety of pet food, including both the domestic manufacture and

importation of pet food, with particular reference to:

- the uptake, compliance and

efficacy of the Australian Standard for the Manufacturing & Marketing of

Pet Food (AS 5812:2017);

- the labelling and

nutritional requirements for domestically manufactured pet food;

- the management, efficacy and

promotion of the AVA-PFIAA administered PetFAST tracking system;

- the feasibility of an

independent body to regulate pet food standards, or an extension of Food

Standards Australia New Zealand’s remit;

- the voluntary and/or

mandatory recall framework of pet food products;

- the interaction of state,

territory and federal legislation;

- comparisons with

international approaches to the regulation of pet food; and

- any other related matters.[1]

1.2

On 16 August 2018, the Senate granted an extension of time for reporting

until 16 October 2018.[2]

Conduct of the inquiry

1.3

Information about the inquiry was made available on the committee

webpage. The committee also invited submissions from interested organisations

and individuals, and received 151 public submissions. A list of individuals and

organisations that made public submissions, together with additional

information authorised for publication is at Appendix 1.

1.4

The committee also considered two petitions which were tabled in the Parliament

during the inquiry. Petition No. 864, which contained 81 021 signatures, raised

concerns about food safety regulations for pet food. The petition – which was

coordinated by Ms Christine Fry and Mr Peter Fry – asked that the Senate consider

the recommendations of the committee's inquiry into regulatory approaches, to

ensure the safety of pet food.[3] Petition No. 865, which contained over 14 500 signatures collected by the

consumer group CHOICE, called for both 'stronger pet food regulation' and the

enforcement of mandatory standards.[4]

1.5

The committee held public hearings on 28 August 2018 and 29 August 2018

in Sydney, NSW.

1.6

A list of witnesses who appeared at the hearings is at Appendix 2.

Submissions and Hansard transcripts of evidence may be accessed through the

committee's website.[5]

Acknowledgment

1.7

The committee thanks all the individuals and organisations who made

submissions to the inquiry. The committee particularly thanks those individuals

who shared personal experiences and stories about their pets and companion

animals. The committee acknowledges the emotional impact of these accounts, and

thanks witnesses and submitters for their contributions.

Note on references

1.8

References to Hansard are to the proof transcript. Page numbers may vary

between the proof and the official (final) Hansard transcript.

Structure and scope of the report

1.9

The report is divided into six chapters. Chapter 1 provides an overview

of pet ownership, and pet food controls in Australia.

1.10

Chapter 2 considers a number of pet food safety incidents that have

occurred in recent years, including a spate of megaesophagus cases in dogs

throughout 2017 and 2018.

1.11

Chapter 3 discusses the regulatory frameworks in place to regulate the

pet food industry in other jurisdictions, such as the United States of America

(US). The chapter also provides an overview of Australia's self-regulation

model, and how this interacts with state and territory laws, importation laws,

and Australian Consumer Law.

1.12

Chapter 4 considers methods to enhance the safety and integrity of pet

food in Australia with focus on the Australian Standard. Chapter 5 considers the

major issues raised by submitters and witnesses with regard to the pet food

industry, including concerns about efficacy and product recall. Chapter 6

considers methods to strengthen the existing reporting regime and Chapter 7

provides the committee's comments and recommendations.

1.13

The committee notes that a number of submitters and witnesses expressed

their views regarding pet diets. Although the committee has considered evidence

from a number of veterinary professionals and academics in the field of

veterinary nutrition and pathology, matters relating to dietary and nutritional

advice are beyond the terms of reference of the inquiry. Therefore, the

committee is not in a position to describe the adequacies of a commercial or

raw food diet for Australian pets or to test their veracity. Rather, the terms

of reference required the committee to consider the transparent and effective

regulation of the pet food industry, including the manufacturing, marketing,

and supply of pet food.

Pet ownership in Australia

1.14

According to a report by Animal Medicines Australia (AMA), there are

more than 24 million pets in Australia today. Australia has one of the

highest rates of pet ownership in the world, with 62 per cent of Australian

households owning at least one pet. Thirty-eight per cent of households have at

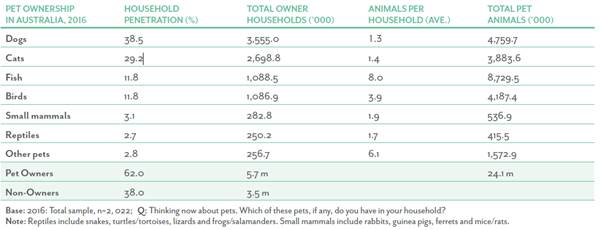

least one dog, while 29 per cent have at least one cat.[6] These figures are summarised in Table 1.1 below:

Table 1.1 – Pet ownership in Australia, 2016

Source: Animal Medicines

Australia, Pet ownership in Australia, 2016, p. 9.

1.15

Over time, there have been changes in the way Australians view their

household pets. Evidence suggests that pets are no longer viewed simply as

animals, but have become 'humanised' to the point that they are considered by

some to be members of the family. The AMA's 2016 survey found that there has

been a significant increase in the proportion of owners who see their pets as a

'fur babies' rather than as mere companions.[7] Amongst dog owners, 64 per cent now see their pet as a family member while 23

per cent see their dog as a companion. The statistics are similar for cat

owners.

1.16

The pet food industry is currently worth over $4 billion—an

increase in worth of 35 per cent since 2013.[8] Global figures show that in 2017, the pet food market was worth $94 billion.[9]

1.17

The two converging trends of the 'humanisation' of pets on the one hand,

and the burgeoning pet food industry on the other, has resulted in the 'premiumisation'

of pet supplies and services. According to the AMA, pet owners are increasingly

opting to spend more money in the hope of providing their pets with the best

possible life. More often, pet owners are purchasing products from specialty

pet superstores, rather than at supermarkets. At the same time, the market for

pet treats and healthcare products has continued to growing rapidly, as has the

market for natural and organic pet food products.[10]

1.18

It is therefore unsurprising that pet owners have high expectations

regarding the quality of domestic and imported pet food that they purchase.

Pet food controls in Australia

1.19

While there is no current national regulatory framework to control the

domestic manufacture or importation of pet food, it is subject to various

standards and codes of practice.

1.20

The pet food industry in Australia is managed under a self-regulation

model and the Pet Food Industry Association of Australia (PFIAA) is the peak

body for the pet food industry. Under the existing structure, members of the

PIFAA must comply with the terms of a National Code of Practice which sets out

the minimum standard expected for the care, management and trade of companion

animals. Membership of the PFIAA is conditional upon a member's ongoing

compliance with the National Code.

1.21

In addition to the National Code, the PFIAA relies on sector specific

standards and guidelines, and in particular, the Australian Standard for the

Manufacturing and Marketing of Pet Food (Australian Standard). This standard

was first published in March 2011 as Australian Standard 5812:2011. Thereafter,

a revised version of the standard, referred to as AS5812:2017, was reissued in

2017 following a review by Standards Australia.

1.22

The Australian Standard is not a publicly available document. It is

available for purchase on the SAI-Global website. As a consequence, many

submitters to the inquiry were not aware of the existence, let alone the

contents of the standard. This circumstance has denied consumers important

information which they could otherwise draw on to hold manufactures to account

for the pet food they produce and the labelling on their products.

1.23

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA)

regulates pharmaceutical products, complementary medicines and supplements

(such as vitamins and glucosamine) for pets. The APVMA is also responsible for

the regulation of pesticides (including worm and flea treatments).[11]

1.24

The states and territories have legislation in place for pet meat and

pet food. While these laws are primarily aimed at ensuring the safety of meat

for human consumption, the legislation also includes provisions which provide

for the directing of animal products from the human food supply chain into the

pet meat/food supply chain. [12]

1.25

In addition to the Australian Standard, other controls include the Competition

and Consumer Act 2010 which is enforced by the Australian Competition and

Consumer Commission (ACCC). This legislation provides general and specific

consumer protections covering misleading and deceptive conduct as well as

unconscionable conduct, unfair practices, consumer transactions, statutory

consumer guarantees, a standard consumer product safety law for consumer goods

and product-related services.

1.26

The Biosecurity Act 2015 requires the Department of Agriculture

and Water Resources (DAWR) to regulate pet food that is imported into

Australia.[13] This responsibility is limited to the management of biosecurity risks

associated with imported products. In addition, DAWR is responsible for

providing certification to pet food products destined for export in accordance

with the Export Control Act 1982.

Pet Food Controls Working Group 2009 – 2012

1.27

In May 2009 – following a number of pet food safety incidents in 2008

and 2009 – a Pet Food Controls Working Group (PFCWG) was established by the

Primary Industries Ministerial Council (now Agriculture Ministers' Forum). The

Working Group was tasked with examining the need for additional mechanisms to

manage the safety of imported and domestically produced pet meat and pet food.

The terms of reference of the working group were subsequently extended to allow

it to consider the Australian Standard (AS5812:2011).

1.28

Chaired by the then Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

(now Department of Agriculture and Water Resources), the PFCWG comprised the

NSW Department of Primary Industries, the Victorian Department of Primary

Industries, Safe Food Production Queensland, the Australian Veterinary

Association (AVA); RSPCA Australia, and the PFIAA.

1.29

The PFCWG considered three options to manage the safety of imported and

domestically produced pet food in Australia – self regulation, co-regulation

and comprehensive regulation. To inform its deliberations, it requested that

the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences

(ABARES) undertake an economic assessment of the different policy options for

managing the safety of imported and domestically produced pet food.

1.30

The PFCWG considered the nature and management of pet food safety

incidents that had taken place over previous years and determined that, with

the exception of one matter, it was unlikely that regulation would have

prevented these incidents and that there had not been a true market failure. It

noted, however, that the scale of the pet food safety incidents could have been

reduced with 'better reporting and response arrangements'. On the basis of its

findings, the PFCWG held the view that there was no justification for new

official oversight of pet food manufacturing.[14] Its view was supported by the findings of the ABARES economic assessment which

found that:

...self-regulation is the preferred approach to

industry-specific consumer protection to avoid unnecessary regulatory burden on

business and the community more broadly...

Self-regulation is a market response to information market

failures and is likely to be the most cost-effective policy option to manage

pet food safety in Australia for a number of reasons...[15]

1.31

However, the ABARES report cautioned that the 'critical issue' that

would determine the success of a self-regulation approach would be the level of

uptake to and compliance with the standard. It concluded:

If significant pet food safety issues arise in the future

through, for example, inadequate compliance with the Australian Standard, there

may be a need to consider cost-effective options to increase compliance. The

preferred approach, at least initially, would be to encourage voluntary

compliance with the Australian Standard. However, if this proves unsuccessful,

there is always the option to reconsider a co-regulation approach where the

Australian Standard is enforced by government.[16]

Development and review of the Australian Standard 2009 – 2017

1.32

Prior to the development and publication of the Australian Standard, the

industry was guided by the Code of Practice for the Manufacturing and

Marketing of Pet Food (the code). The code was developed and managed by the

PFIAA.

1.33

In 2009, shortly after a government-initiated Pet Food Controls Working

Group (PFCWG) was established, the PFIAA announced a commitment to update and

replace the code with a comprehensive Australian Standard. The standard was

developed in 2011 to provide an official standard for the production and supply

of manufactured pet food for dogs and cats.[17]

It was developed by an industry-stakeholder working group established by

Standards Australia following a public consultation process. The working group

comprised representatives from the Department of Agriculture, RSPCA, AVA, PFIAA

and the Victorian Department of Primary Industries.[18]

1.34

The Australian Standard was published on 10 March 2011 as AS5812:2011.

It provides guidelines for the safe manufacture and marketing of pet food

intended for consumption by domesticated cats and dogs.

1.35

In November 2017, the Australian Standard was reviewed and updated to

ensure that it 'remains an appropriate and contemporary document guiding

certified companies in pet food manufacture and labelling'.[19] The major changes made to the Australian Standard included reference to raw pet

foods (as well as commercially processed) within the standard; reference to

European pet food standards and upgrading labelling requirements to provide

further relevant information for consumers and veterinarians.[20]

1.36

Amongst these key changes to the Australian Standard was that of the

incorporation of references to pet treats as well as pet meats. Prior to 2017,

the Standard for the Hygienic Production of Pet Meat applied to pet meat

alongside various state and territory legislation specific to pet meat,

primarily aimed at ensuring that pet meat does not enter the human food chain.[21] Developed in 2006, this standard details minimum hygiene requirements in the

processing of animals used in the production of pet meat.

1.37

The PFCWG noted, in its 2012 report, that the pet meat standard was

'only implemented via regulation in some jurisdictions'.[22] Furthermore, it noted that there was no pet meat industry body to implement its

standard.

1.38

The incorporation of pet meat into the Australian Standard in November

2017, was recognised as an important step toward aligning Australia's standards

with international standards. The alignment had been suggested by bodies,

including the AVA, which noted in its advice to the PFCWG in 2012, that such an

alignment would 'provide improved products for feeding of dogs and cats in

Australia and have a very positive impact on food safety for dogs and cats'.[23]

Requirements under the Australian Standard

1.39

The Australian Standard specifies requirements for the production and

supply of manufactured food for domesticated dogs and cats:

This Standard covers production of pet food, including pet

meat from sourcing and receipt of ingredients to storage, processing (including

heat treatment), packaging, labelling and storage of production in order to

assure its safety for pets. It also includes instructions for the uniform

application of information provided on labels.[24]

1.40

The Australian Standard is focused on 'the safety of multi‑ingredient,

manufactured food for feeding to pets', as well as ensuring that products are

'accurately labelled and do not mislead purchasers'.[25] It details requirements for management and production practices at pet food

manufacturing establishments to ensure the safe production of pet food,

including, a quality assurance system.

1.41

A brief overview of the Australian Standard, and the requirements for

manufacturing, labelling, marketing and nutrition, is outlined below.

Manufacturing

1.42

The first section of the Australian Standard provides instruction on the

management and production practices of pet food manufacturing establishments.

Manufacturing establishments are required to have a documented quality

assurance system and a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan as

per the principles set out by the Codex Alimentarius Commission.[26]

1.43

The Australian Standard also specifies the requirements for building and

construction to ensure that the premises where pet food is manufactured, and

the equipment used to produce it, are safe, hygienic and free from

contamination. Guidelines are set out for plant and equipment, cleaning and

sanitising practices, pest control, sampling and testing, record keeping, and

product tracing and recall practices.

1.44

With regard to ingredients, pet food manufacturers must ensure that all

raw materials used in pet foods comply 'with the relevant Australian

regulations'.[27] Additional information about pet food ingredients is available from the PFIAA,

and includes adherence to the APVMA's Maximum Residue Limits (MRL), and the

National Feed Standard (NFS).[28]

1.45

The sourcing and purchasing of raw materials must also be documented,

and storage areas must be maintained to minimise the risk of damage,

contamination, and unintended mixing or deterioration of ingredients or

packaging materials.[29]

1.46

The Australian Standard provides further guidance on the heat treatment

and process control of pet food. It states that where temperature control is

critical to product safety and quality, temperatures must be controlled,

monitored and recorded. Process controls should have identified parameters

relating to the use of additives, adjustment of pH, water activity, commercial

sterility, and the use of mould-growth inhibitors. Processes and procedures for

the storage and handling of chilled and frozen ingredients should also be in

place. All processes should be clearly identified in the HACCP plan.

Labelling

1.47

The nutritional requirements of the Australian Standard dictate that pet

food should follow the guidelines provided for in an international nutritional

publication such as the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) Official

Publication or the FEDIAF (European pet food association) Nutritional

Guidelines. The development of these publications is considered in the

following chapter.

1.48

Labels should include an accurate description of the style, flavour or

purpose of the pet food and should list all major ingredients and additive

classes, with percentages included. For the purpose of naming, 'meat' signifies

any part of an animal, other than feathers, which contains protein, and is

ordinarily used in a food by dogs or cats, whether fresh, chilled, frozen or

dried. The standard also provides details about the percentage of meat required

in the food before a product can be labelled as a variety of meat, a meal

containing meat, a product with meat components, or a product with meat

flavour. Similar requirements apply across hermetically sealed or retorted pet

food, wet pet food, and dry pet food. These labelling thresholds are detailed

in the standard.[30]

1.49

Labelling requirements provided in AS5812:2017 also detail the manner in

which pet food should be identified. Packaged pet food must be marked with an illustration

of the whole of the body, or the head, of a dog or cat, with the words 'PET

FOOD ONLY' clearly displayed in legible print.

1.50

Nutritional information should be presented in a nutritional information

panel on the packaging, with a statement of guaranteed or typical/average

composition. A measurement of metabolisable energy, as required by international

nutritional publications, should also be included. The stated composition of

ingredients should be validated by a regular sampling and testing program.

1.51

The standard requires that the packaging display a statement of

ingredients, presented in an informative and consumer-friendly manner. This

includes food additives, which should be listed in accordance with the

applicable Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Food Standards Code

number, or by a specified class name.

1.52

Noting the importation requirements on certain pet foods, dog food that

is irradiated should be labelled as such, with the inclusion of a warning that

the food 'must not be fed to cats'. Any cat food or food intended for both cats

and dogs must not be irradiated.[31]

Marketing

1.53

This section of the standard requires that advertising does not

contradict or negate any information that appears on the labelling of a

product. Generally, marketing should not be misleading, misrepresentative or

disparaging of competitors' products.[32]

Nutrition

1.54

To adhere to the Australian Standard, pet food manufacturers must ensure

that their pet food products comply with the recommended nutritive requirements

set out in an international nutritional publication such as the AAFCO Official

Publication or the FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines. The pet food must be labelled

as 'nutritionally complete', and products that are designed for a specific life

stage should have labelling that clearly states its purpose. Examples include:

'nutritionally complete for the maintenance of adult dogs', or 'nutritionally

complete pet food for growing kittens'.

1.55

Foods that do not meet the minimum recommended nutritive requirements

for cats or dogs, as defined by an international nutritional publication,

should be labelled as 'intended for occasional or supplemental feeding'. The

label should clearly state that the food is 'not nutritionally complete', or is

intended as a 'supplement', 'complementary food', 'snack' or 'treat'.[33]

1.56

Where the food is intended for therapeutic or dietary purposes, the

product must comply with the provisions of the Agricultural and Veterinary

Chemicals Code Regulations 1995. All therapeutic pet foods classified as

excluded nutritional or digestive products must be labelled with advice that a

veterinary opinion be sought before introducing the product to an animal.

Therapeutic pet foods deemed veterinary chemicals must first be registered with

the APVMA before being eligible for sale.[34]

Adherence to the Australian

Standard

1.57

While adherence to the Australian Standard is voluntary for PFIAA

members, compliance is strongly encouraged. The PFIAA indicated that the

Australian Standard has been widely adopted by its manufacturing members and

that estimates suggest that more than 95 per cent by volume of manufactured pet

food sold in Australia is supplied by PFIAA members.[35] Put differently, PFIAA member companies, all of which adhere to the Australian

Standard, provide an estimated 95 per cent or more prepared pet food sold in

Australia.

Recent developments

1.58

On 7 May 2018, the Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources,

the Hon David Littleproud MP, wrote to states and territories asking them to

support an independent review into the safety and regulation of pet food.[36] Noting a need to reconsider how the pet food industry operates, Minister

Littleproud indicated that three states had voiced their support for such

review.

1.59

The committee received updated information at a public hearing on 29

August 2018 that all state and territory governments had since provided their support

for the review, and that DAWR is in the process of establishing a working group

to undertake the review. Potential members of the working group include the AVA,

the PFIAA, RSPCA Australia as well as the Animal Health Committee (AHC).[37]

1.60

To give further context to these recent developments, the next chapter

will discuss a series of pet food safety incidents that have occurred locally

and overseas. In particular, the spate of megaesophagus cases in dogs

throughout 2017–18 is considered. The megaesophagus cases were consistently

referred to in evidence to the committee; to highlight the shortcomings of the

current system, and the need to consider enhanced safety and integrity measures.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page