Tessa Satherley, Economic Policy and Dr

Daniel May, Science, Technology, Environment and Resources

Key issue

Recent natural disasters have been traumatic and costly for Australian communities, and recovery will take many years. Under climate change projections, natural disasters are expected to impose a worsening burden on emergency responders and communities, and to further challenge the management capabilities of governments. The 47th Parliament has an opportunity to build on its predecessor’s legacy of reforming federal disaster management arrangements, and careful scrutiny of Australian Government spending to promote preparedness, response and recovery.

This article recaps recent disasters and climate

change projections, and outlines current governance arrangements for disaster

response and climate adaptation. It explores key issues for the 47th Parliament,

including the inadequacy of federal–state emergency management arrangements in

light of recent disasters; the right balance between investment in prevention,

mitigation and response; and planning for the growing fiscal impact of natural

disasters.

Background: natural disasters in Australia

Australia has always experienced natural disasters,

but their frequency, severity and cost is increasing as climate change

progresses. As concluded in the 2020 report of the Royal Commission into

National Natural Disaster Arrangements (RCNNDA): ‘Natural disasters have

changed, and … the nation’s disaster management arrangements must also change’

(p. 22).

Recent major disasters

During the 46th Parliament, Australia experienced

multiple large-scale disasters in succession, starting with the continuation of

the 2017–19 drought. The year 2019 was Australia’s warmest and driest

year ever recorded. Climatologists said the drought surpassed

the Federation, Second World War and Millennium droughts in severity. Parliament

heard that farmers

struggled to put food on their own tables, and ‘financial wellbeing, mental

health, employment and family relationships’ suffered across broader rural and

regional communities (p. 39). The impact

on Murray–Darling Basin communities- human and ecological- was severe. Multiple mass

fish die-offs occurred, and the competing environmental and socio-economic stresses

threatened to ‘destroy

the Murray–Darling Basin plan’ (see the article ‘Water, including the Murray-Darling Basin’ in this Briefing book).

Drought is sometimes described as a tragedy

in slow motion, requiring different response mechanisms to more sudden disasters.

The arrangements for federal–state cooperation on drought measures are set out

in the 2018 National

Drought Agreement. The 2019–21 Senate

Inquiry into the Federal Government’s Response to the Drought identified gaps

in the available support payments, including restrictive eligibility criteria, burdensome

application processes, unclear communication about available support and a

pattern of mostly ‘reactive’ expenditure.

The 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires were characterised by an unprecedented

extent of high-severity fire across eastern Australia. Thirty-three

people died, 24–33 million

hectares were burnt, a pall of

smoke covered east coast cities and thousands were hospitalised

due to smoke inhalation. Researchers have warned some

rainforests and peatland may never

recover. At the commencement of the 47th Parliament, some survivors are still in

temporary accommodation.

The Morrison Government

was criticised for allegedly failing to act decisively on warnings

of a catastrophic fire season, reducing aerial firefighting funding, an ad-hoc

approach to resource deployment and poor communication with relevant state

authorities- a state firefighting chief claimed he first learned of planned Australian

Defence Force (ADF) deployments through the media. Longer-term

recovery measures have been found wanting, with

ongoing homelessness in fire-affected regional communities in Victoria and NSW.

The RCNNDA,

the Senate

Finance and Public Administration Committee and separate

state inquiries reported on the disaster, and the RCNNDA

recommended an overhaul of national disaster management arrangements.

The catastrophic February–March 2022 east coast floods saw rainfall

records fall across south-east Queensland and north-east NSW, leading to flash and riverine flooding from Maryborough in Queensland

to Grafton in NSW. Flooding also occurred on NSW’s Central Coast,

in Sydney, in the Illawarra

and on the NSW South Coast. In Lismore, northern NSW, the

unexpectedly high flood peak of 14.4 metres (dwarfing the

previous record of 12.1 metres) meant

thousands had to be rescued. Local reporting suggested most rescues

were conducted by civilians, as the scale of the task

overwhelmed official response capabilities. More than 20 people

died nationally, and the Insurance Council of Australia

estimated $3.35 billion in insured losses, making it ‘the

costliest flood in Australia’s history’.

Criticism of the federal, state and local flood response has been

particularly fierce in northern NSW, where residents and media reported triple zero

calls going unanswered, civilians

chartering their own helicopters to meet the unmet need for

aerial rescues and food drops; miscommunication

about ADF deployments; the unequal

provision (at first) of federal financial support to flood victims in adjacent electorates, and mixed

messages from federal and local government about Lismore’s future,

preventing informed repair and reconstruction decisions. The National

Resilience and Recovery Agency (NRRA) was forced to defend its

earlier decision ‘to omit Lismore from its priority areas for flood mitigation

funding’ and the slow delivery of relief payments. The NSW Government has commissioned an independent inquiry, which at the

time of writing was hearing from flood victims in northern NSW. Media report that the inquiry has ‘heard countless tales of government unpreparedness during the peak of the crisis, in the recovery centres

and as efforts continue to find accommodation for the thousands left homeless’.

The Inquiries and reviews database catalogues 315 disaster inquiries and reviews from 1886 to 2020, and all recommendations from 186 inquiries and reviews from 2003 to 2020. Inquiries provide a space for survivors to tell their stories. However, some researchers have suggested less adversarial and more holistic methods of identifying lessons, and others have argued for greater focus on implementation.

The natural

disaster and extreme weather outlook

The 2020 RCNNDA report stated that ‘Australia’s

disaster outlook is alarming’, with climate change exacerbating bushfires,

extreme rainfall and flooding (p. 68),

although the CSIRO has also reported that the implications of climate

change for droughts, damaging hail, tropical cyclones and other storms are less

clear.

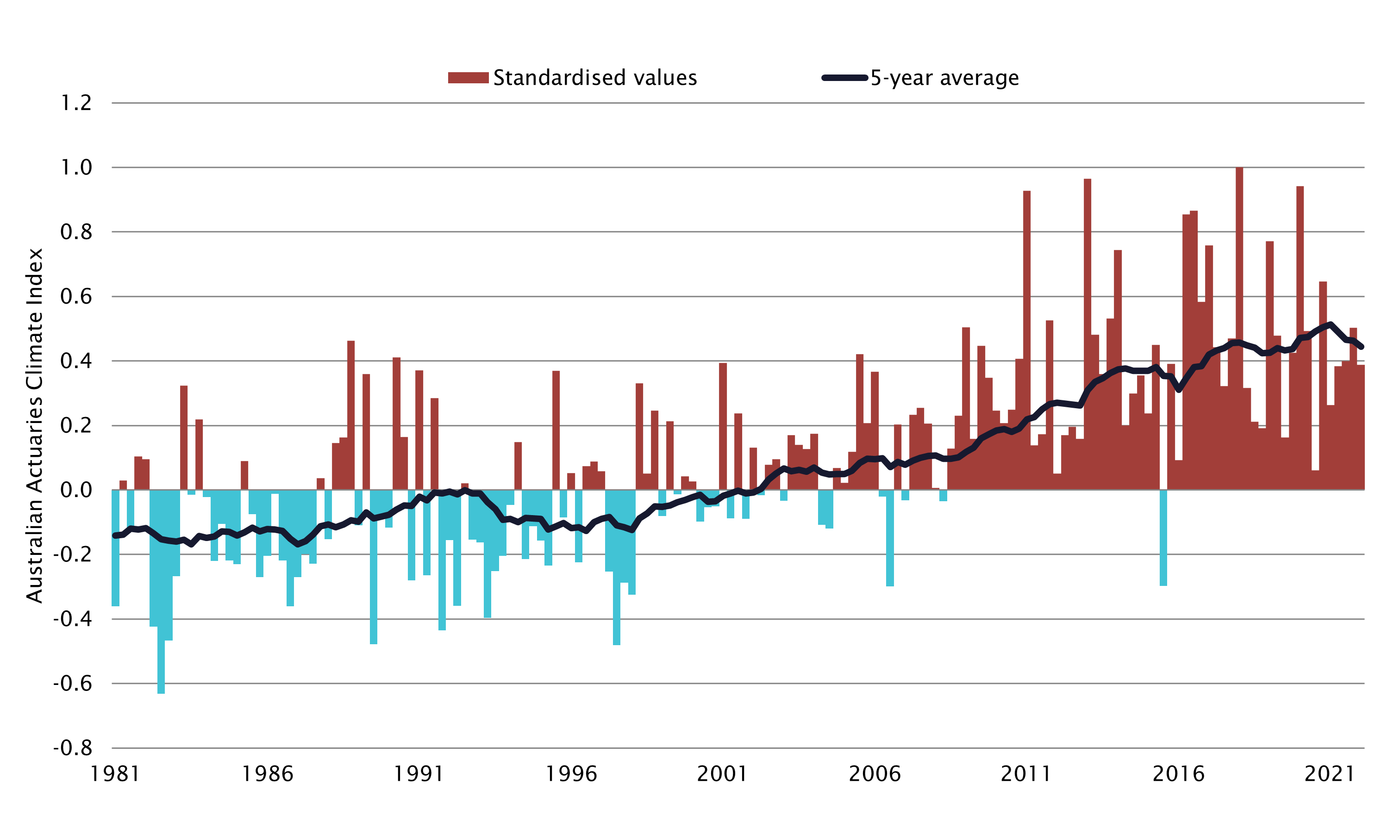

Actuaries specialise in assessing the financial consequences of

risks, and are often employed by insurers, banks and investment managers. The Australian Actuaries Climate

Index (AACI) tracks changes in the frequency of extreme

temperatures, heavy precipitation, dry days, strong wind and changes in sea

level across Australia, ‘because extremes have the greatest potential impact on

people and, often, the largest cost to the economy’. The AACI shows

significantly worsening extreme weather risk, shown by an index number above

zero (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Australian Actuaries

Climate Index

Source: Actuaries

Institute, Australian

Actuaries Climate Index website.

The RCNNDA quoted evidence from the Australian Business

Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities that ‘Direct and

indirect disaster costs in Australia are projected to increase from an average

of $18.2 billion per year to $39

billion per year by 2050, even without accounting for climate change'.

The Business Roundtable, in partnership with

Deloitte Access Economics, published an Update

to the economic costs of natural disasters in Australia in October 2021, which concluded that even

under a low emissions scenario, the cost of natural disasters in Australia is

estimated to increase to $73 billion per year by 2060. Scenarios with higher global emissions can

expect commensurately higher disaster costs (p. 1). Under a high-emissions, 3 °C warming scenario:

By 2060 costs reach

$94 billion, representing a 29% increase relative to the low emissions

scenario. Over the next 40 years the different trajectories will lead to a $125

billion difference in cumulative cost in present value. Even if a low emission

scenario is achieved, the cost of natural disasters is forecast to be $1.2

trillion in cumulative costs over the next forty years.

Current disaster response and climate adaptation arrangements

Strategic

foundation: ‘shared responsibility’

The 2011 National

strategy for disaster resilience (NSDR), negotiated

through the former Council of Australian Governments, is the strategic foundation

of current federal disaster arrangements. It frames disaster resilience as

‘a shared responsibility for individuals, households, businesses and

communities, as well as for governments’. It has

an objective of ‘community empowerment’, but also outlines very significant roles

for all levels of government.

Academics have criticised the ‘shared responsibility’ framing for

its ambiguity on

the division of responsibilities, and for the tension

between the placement of governments at the centre of disaster risk management and

the emphasis on ‘community empowerment’.

Further, the Productivity Commission

has warned of ‘the risk that the expectation of government

financial assistance will create “moral hazard” … by reducing incentives for

individuals and businesses to take out insurance and invest in mitigation’

(p. 25) - and that the same risk of moral hazard could apply to Australian

Government assistance to states and territories (p. 86).

Federal

disaster response arrangements

Constitutional power for emergency management largely rests with

the states and territories. The Australian government crisis management framework

(AGCMF), first released in 2012, outlines that ‘states

and territories are the first responders to any incident that

occurs within their jurisdiction and have primary responsibility for the

protection of life, property and the environment within the bounds of their

jurisdiction’ (p. 7).

However, the AGCMF acknowledges

that ‘the Australian Government possesses operational and strategic

capabilities that can ensure decisive action is taken during a nationally

significant crisis’ and ‘recognises the expectations of the

Australian public that it will take a leadership role in nationally significant

emergencies’ (p. 7).

The AGCMF outlines the financial and

non-financial assistance the Australian Government may provide at various

phases during a crisis. The

main forms of direct Australian Government financial support for individuals are

the Australian

Government Disaster Recovery Payment and the Disaster

Recovery Allowance, delivered via Services Australia

(see ‘Further reading’).

The Australian Government can also provide disaster funding to

states and territories. Most is coordinated through National Cabinet or Council on Federal

Financial Relations mechanisms.

The main formal mechanism is an Australian Government ‘disaster

relief’ payment, typically a contingent payment made to a state or territory on

a cost-sharing basis. The bases for these payments are the Intergovernmental

Agreement on Federal Financial Relations, the Natural Disaster Relief

and Recovery Arrangements (NDRRA) and the Disaster Recovery

Funding Arrangements (DRFA).

In essence, a state or territory makes an application to the Australian

Government for payments in response to an eligible emergency, and some costs

are shared. The Australian Government has also historically made a range of

ad hoc and one-off payments for specific disasters.

These expenditure types are budgeted as ‘contingent payments’. In

simple terms, the legislative and governance frameworks are in place to enable

these payments following an eligible event, but the timing and quantum of

funding are unknowable- and not forecast- before the trigger event (see ‘Natural

disaster expenditure in the Australian Government Budget’ below).

Additional assistance may be provided through disaster resilience

programs, grants to local government and non-government organisations, one-off

payments to individuals or businesses and special tax concessions or exemptions.

Under the Australian government

disaster response plan (COMDISPLAN), the Australian Government may

also provide non-financial aid to the

states and territories, such as mapping services, planning expertise and

physical and logistics support (for example, the airlift capabilities of the ADF).

This non-financial support is coordinated through Emergency Management Australia (EMA), a division of the

Department of Home Affairs. EMA also provides national ‘24/7 all-hazards

situational awareness and monitoring’ (p. 14) through the National Situation Room, formerly

known as the Australian Government Crisis Coordination Centre.

Changes to

natural disaster arrangements during the 46th Parliament

The Morrison Government

oversaw changes to the institutional architecture for managing national-scale

emergencies. Under the National Emergency Declaration Act 2020, the Governor-General, on the advice of

the Prime Minister, may now declare a ‘national emergency’.

This makes a range of powers available to ministers

to assist with response and recovery, including the ability to suspend the usual administrative rules welfare

recipients must comply with in order to receive Services Australia payments,

and the ability to mandate the reporting of emergency stockpiles and assets.

Chapter 7 of the RCNNDA

report discussed the role of the ADF following the 2019–20 bushfires,

and noted ‘a lack of understanding about the role, capacity and capability of

the ADF in relation to natural disasters’ (p. 186). In response, the COMDISPLAN was

updated in December 2020 to outline the process for the Australian Government

to respond to requests for assistance from state and territory governments,

including for ADF assets.

The NRRA was launched in May 2021. It brought together the former National

Bushfire Recovery Agency and the National Drought and North Queensland Flood

Response and Recovery Agency, in addition to disaster-related functions from

other departments. The NRRA was intended to ‘provide support to local

communities during the relief and recovery phases following major disasters’,

and also provide advice on mitigation programs for future major disasters.

Former emergency managers have been critical of

the NRRA. For example, a former Commissioner of the ACT Emergency Services

Authority has criticised it for undertaking ‘almost no’ disaster mitigation work, and argued its creation- sitting alongside EMA- was ‘a recipe

for duplication and administrative hubris’.

The Emergency Response Fund (ERF) was created through the Emergency Response Fund

Act 2019. As outlined in the Parliamentary

Library’s Bills digest, the ERF was initially funded

through the transfer of approximately $4 billion from the Education

Investment Fund, and is to be used for financial assistance for projects,

services or technologies aimed at enhancing disaster recovery or improving

post-disaster resilience.

The Act enables the Government to access up to $150 million

each year to fund emergency response and recovery efforts following natural

disasters, and up to $50 million each year to fund initiatives that build

resilience and reduce the risk of future disasters.

As at 30 June 2021, the ERF was valued at $4.7 billion. Following

the 2019–20 bushfires and 2022 floods, the Morrison Government faced criticism for not having disbursed the full available annual funding from the ERF

since its foundation. According to the Department of Finance, the ERF paid out $50 million in 2020–21 and a total of $150 million in 2021–22 as at 31 March 2022.

In the last days of the 46th Parliament, the Treasury Laws Amendment

(Cyclone and Flood Damage Reinsurance Pool) Act 2022 established a reinsurance pool for cyclone damage backed by a

$10 billion Australian Government guarantee. While the legislation was

originally developed to address cost pressures in northern Australia,

parliamentary debate- against the backdrop of the 2022 floods- focused on the

possibility of extending the model to cover all flood or natural disaster risks

nationally, to address other communities’ worsening risk profile under climate

change (see ‘Further reading’).

Both major parties, the Insurance Council of Australia (ICA) and

most other stakeholders supported the reinsurance pool. However, the ICA’s 2022 policy

platform Building

a more resilient Australia called for greater investment

in disaster mitigation measures as the only way to sustainably reduce natural

peril insurance premiums long term. The ICA also called for federal–state–local

government collaboration on land planning and development reform in

consideration of worsening extreme weather risk.

In disaster management, mitigation refers to steps to lessen or minimise the adverse impacts of foreseeable hazardous events, such as building a flood levee, cyclone-proofing a house or creating a fire break. The word is used in that sense in this article. In the context of combatting climate change, mitigation refers to ‘making the impacts of climate change less severe by preventing or reducing the emission of greenhouse gases’. Since the UK’s landmark 2006 Stern Review, experts have recommended an economic strategy of both reducing global emissions as fast as possible and investing early in climate change adaptation and/or disaster mitigation, to manage locked-in climate change impacts. Recent Australian Government-funded mitigation programs include the Preparing Australia Program, the Disaster Risk Reduction Package, the Future Drought Fund and the National Flood Mitigation Infrastructure Program.

Climate adaptation

governance arrangements

The former Council of Australian Governments agreed a federal

framework on climate change adaptation roles and responsibilities in 2012. Under this framework, the Australian Government’s role and

responsibilities include:

-

providing leadership on national adaptation

reform

-

managing Australian Government assets and

programs

-

providing national science and information

-

maintaining a strong, flexible economy and a

well-targeted social safety net.

Australia’s National climate resilience

and adaptation strategy 2021–2025 was

updated and released in October 2021,

prior to COP26 (see the article ‘Climate change and emissions reduction’ in this Briefing book). The strategy’s 3

main objectives are to:

-

drive investment and action through

collaboration

-

improve climate information and services

-

assess progress and improve over time.

Critics have said the strategy lacks

substance, citing its lack of specific policies, detailed targets and

funding. Other commentators have conceded its limitations, but see it as ‘a good start’.

The national adaptation strategy’s second objective will largely

be met by the Australian Climate Service,

established in July 2021.

The service functions by compiling Australian

Government climate and natural hazard research into one platform,

which can be used to increase the capacity to plan and prepare for natural

disasters and ‘build a more resilient Australia’.

The service was provided with $209.7 million over 4 years

(and $37.3 million annually ongoing) in the 2021–22

Budget (p. 66).

Natural disaster expenditure

in the Australian Government Budget

Extreme weather is already resulting in significant unplanned Budget

expenditure, although budgetary reporting conventions make monitoring the

overall picture challenging.

The Morrison Government’s 2022–23 Budget anticipated significant

expenditure from past natural disasters. For example, Budget paper

no. 2: 2022–23 included:

-

the multi-billion dollar cross-portfolio ‘Flood

Package’ measure in response to the east coast floods (pp. 61–63)

-

an additional $116.4 million over 3 years from

2021–22 for Black Summer Bushfire Recovery Grants (p. 155)

-

at least $20.1 million for ‘Disaster Support’,

including the establishment of a national emergency management stockpile,

mental health support for first responders and support following flood and

storm events in 2021, to be delivered jointly with the states (p. 159).

Forward estimates in the Budget for ‘natural disaster relief’ in

aggregate only show the expected future expenditure due to past disasters.

This is consistent with the funding mechanism by which payments to

the states are contingent on an eligible trigger event (see ‘Federal disaster

response arrangements’ above). The Budget does not make guesses as to whether

and when future trigger events might occur, or how big the funding quantum will

be.

Given this approach, it is unsurprising that Australian Government

natural disaster relief has consistently exceeded previous ‘estimates’ in

recent years (see Table 1), as new widespread disasters occur on the heels

of previous ones.

Table 1 Spending on natural disaster relief: forward estimates and actual expenditure

| $ million |

Forward estimate(a) |

Budgeted amount(b) |

Actual expenditure(c) |

| 2022–23 |

253 |

763 |

TBC |

| 2021–22(d) |

832 |

327 |

5,176 |

| 2020–21 |

2 |

482 |

748 |

| 2019–20 |

10 |

11 |

1,863 |

| 2018–19 |

2 |

17 |

775 |

(a) The

forecast expenditure for the year in the first column according to the

Budget for the year prior.

(b) The expenditure listed for that year in the Budget of the same year.

(c) The expenditure listed for that year in the following year’s Budget.

(d) The figures for this year include funding for the establishment of the

National Recovery and Resilience Agency.

Sources: Australian Government, Budget Paper No. 1: 2022–23, 171–2; Budget Paper No. 1: 2021–22, 191; Budget Paper No. 1: 2020–21,

6–52; Budget Paper No. 1: 2019–20, 5–42; Budget Paper No. 1: 2018–19, 6–43; Budget Paper No. 1: 2017–18, 6–44.

This makes it difficult to use the Budget’s forward estimates to

project the future fiscal burden of natural disaster costs relating to climate

change.

In addition, the ‘Statement of Risks’ in recent

Budgets has been silent with regard to climate-related fiscal risk. This is arguably

at odds with recent prudential advice from the Australian

Prudential Regulation Authority and the Actuaries

Institute.

In contrast, recent Budgets have had a

dedicated section on ‘climate spending’, to clarify the implications of spending

on environmental action for the national debt.

Albanese Government disaster readiness commitments

The Albanese Government's election platform included policies to

implement the Productivity Commission recommendation to invest ‘up to $200

million per year on disaster prevention and resilience’ (to be matched by the

states and territories) through a Disaster

Ready Fund, on top of existing arrangements. (The

Productivity Commission’s 2014 Inquiry into Natural Disaster Funding

Arrangements had reported that ‘Australian Government

mitigation spending was only 3 per cent of what it spent post-disaster’,

p. 9.)

Labor also committed

to establishing a sovereign aerial firefighting fleet, in partnership with

the National Aerial Firefighting Centre

(NAFC) and state and territory governments, and to funding

Disaster Relief Australia to expand its national veterans-led

volunteer corps.

Australia’s National Aerial Firefighting Centre (NAFC) ‘provides a cooperative national arrangement for the provision of aerial firefighting resources for combating bushfires’ (emphasis added). While the NAFC contracts aerial firefighting resources on a national basis, state and territory land management agencies may directly contract resources.

The NAFC recently released the National aerial firefighting strategy 2021–26, which provides an overview of the current NAFC fleet, consideration of the RCNNDA recommendations on national aerial firefighting capabilities and arrangements, and the costs of and opportunities for further aerial firefighting roles.

Traditionally, fire seasons in Australia and North America have been well separated, which allowed for aircraft and personnel sharing. However, fire seasons in both the northern and southern hemispheres are lengthening, placing pressure on resource-sharing and leading to calls from prominent serving and former emergency managers for boosts to our national aerial firefighting fleet capability. In contrast, NAFC’s National aerial firefighting strategy 2021–26 states that Australia already possesses ‘good sovereign fleet capability … albeit largely contracted’, with the exceptions of Large Air Tanker aircraft and - to some extent - Type 1 Rotary Wing aircraft (p. 17).

Other high-level Labor

election commitments included:

-

reducing red tape around accessing disaster resilience funding

-

improving the efficiency of disaster recovery processes

-

assisting with rising insurance premiums in disaster-prone regions

by reducing the risk of expensive damage; that is, through mitigation.

Intense media and community scrutiny is likely to continue as the

new Albanese Government and 47th Parliament navigate the legacy of recent

disasters and federal reforms, and seek to improve the nation’s position to

manage future disasters in a changing climate.

Further reading

Tessa Satherley, ‘Treasury Laws Amendment (Cyclone and Flood Damage Reinsurance Pool) Bill 2022’, Bills Digest, 54, 2021–22 (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2022).

Michael Klapdor, Income Support for Households Affected by Natural Disasters: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2019–20 (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2020).

Karen Elphick, National Emergency and Disaster Response Arrangements in Australia: a Quick Guide, Research paper series, 2019–20 (Canberra: Parliamentary Library, 2020).

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.