Dr Emily Gibson, Science, Technology, Environment and Resources

Key issue

Integrated and sustainable management and use of Australia’s water resources is essential for national water security.

The Murray-Darling Basin, Australia’s most important river system, continues to face critical threats to its health. The Basin Plan, to be jointly implemented by the Australian and Basin state governments, still needs to be implemented in full to secure environmental, social, and economic outcomes for the benefit of all Australians.

Australia is the world’s

driest inhabited continent and experiences high variability in rainfall. Around

10% of annual rainfall reaches waterways, water storages or groundwater

aquifers, while the rest evaporates, mainly through vegetation (p. 2). Much of the country is vulnerable to drought, which affects agriculture, natural ecosystems, human health,

communities and our national economy.

The Millennium drought affected most of southern Australia (other than parts of central Western

Australia) over the period 1997 to 2009, while the return of drought conditions

over much of the country during 2017–19 culminated in severe bushfires in the summer of 2019–20. Conversely, while drought conditions currently

persist in parts of Tasmania, the Northern Territory, South

Australia, and Victoria, southern

Queensland and NSW received a year’s worth of rainfall from

February to early April 2022 and were impacted by severe flooding.

The variability in

Australia’s rainfall is strongly influenced by climate drivers including El Niño, La Niña, the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode. However, the State of the climate report 2020 identifies concerning long-term trends in Australia’s

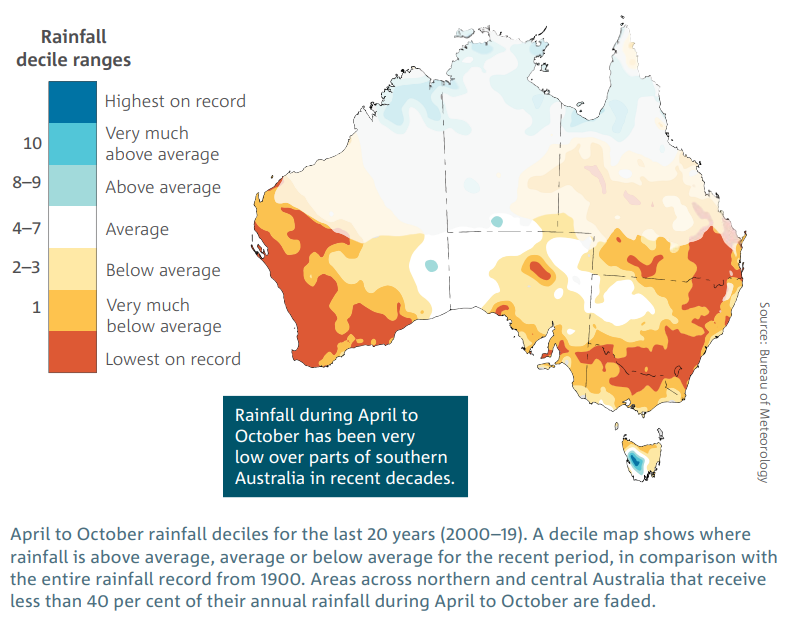

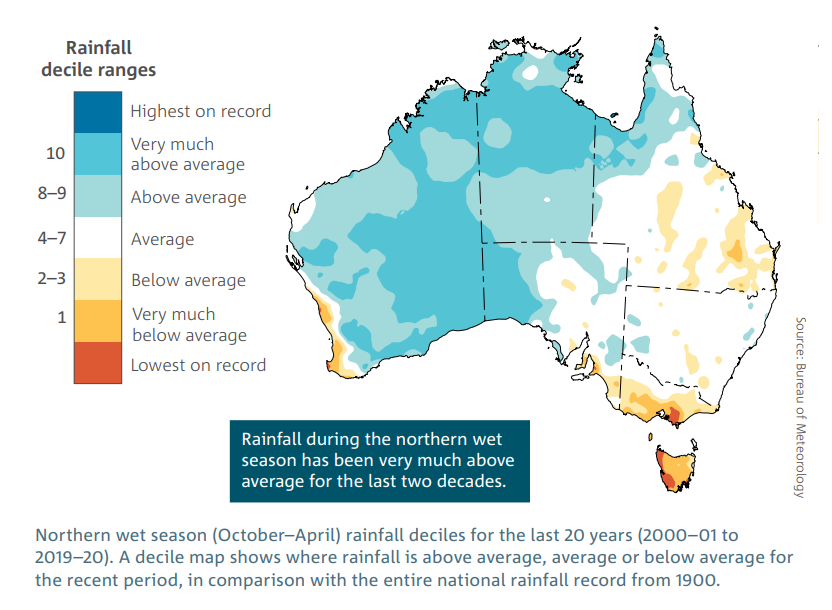

rainfall record (see Figure 1):

There has been a

shift towards drier conditions across the southwest and southeast, with more

frequent years of below average rainfall, especially for the cool season months

of April to October. In 17 of the last 20 years, rainfall in southern Australia

in these months has been below average. This is due to a combination of natural

variability on decadal timescales and changes in large-scale circulation caused

by increased anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. (p. 6)

Figure 1 Rainfall

deciles over the last 20 years

(a) April to

October

(b) the Northern

wet season

Source:

CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology, State of the Climate 2020, (Canberra: Australian Government, 2020),

6–7; reproduced by permission of the Bureau of

Meteorology, © 2022 Commonwealth of Australia.

According to the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth assessment report, climate change projections indicate there will be

less winter and spring rainfall in southern Australia, more winter rainfall in

Tasmania, less autumn rainfall in south-western Victoria and less summer

rainfall in western Tasmania, with uncertain rainfall changes in northern

Australia (p. 11 – 4).

Management of Australia’s

water resources is often viewed solely through the prism of its production

value. For example, 67% of water taken for consumptive use in 2019–20 was

used for agriculture (p. 5). In that

year, the gross value of Australia’s agricultural production was

$61 billion, with $16.5 billion generated from irrigated agriculture. Around 70% of agricultural production is exported, contributing 12% of Australia’s total goods and

services exports (pp. 2; 7). In 2019–20, water markets in Australia had an estimated turnover of $7 billion (p. 4), while the value of water entitlements in the

southern Murray-Darling Basin doubled from $13.5 billion to $26.3 billion in the

5 years to 2019–20 (p. 30).

However, water’s value is not limited to economic impacts. Integrated and sustainable management of Australia’s

water resources underpins broader concerns about water security and ecological significance. Observing that water

security involves complex and interconnected challenges, UN-Water defines water security as:

the capacity of a

population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable

quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic

development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and

water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace

and political stability. (p. 1)

The Australian Government does not have direct constitutional powers for managing water resources; these powers lie with

the states and territories. However, the Australian Government still has an

important role in water policy. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) water reform framework was agreed in 1994, followed by the National water initiative in 2004, and the Howard Government’s $10 billion National plan for water security in 2007.

There remains, however, no

nationally agreed definition of water security in Australia and, over the past

decade, Australian Government engagement in water policy has been oriented to

the augmentation of supply (that is, developing dams) and

reducing the impact of existing regulation on private sector water users (p. 33). The Productivity Commission’s report, National water reform 2020, which recommends renewal and modernisation of the National

water initiative, identifies several opportunities for adopting a more

holistic approach to water security. These include (among others) (pp. 9–12):

- the adoption of best practice water

planning, which takes into account all water uses (including floodplain

harvesting) and provides for the rebalancing of environmental and consumptive

uses as a result of climate change

- improved arrangements to make the best use

of environmental water to achieved agreed (or where possible, better)

environmental outcomes

- securing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ interests in

water, supporting the achievement of the 2020 National Agreement on Closing the Gap, including adopting management measures to achieve cultural flows

and economic outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

- the adoption of best practice urban water

system planning, supported by community-driven objectives for water security,

and additional support to ensure small rural water utilities provide acceptable

levels of service.

Urban and rural water use

Urban uses account for 22% of Australian water consumption. Households paid an average of $3.46 per kilolitre and

industry $0.46 per kilolitre in

2019–20, with the difference driven by factors including the cost of treating

water so that it is suitable for human consumption. Most water, especially for

supply to major urban areas, is sourced from surface water sources such as

rivers and lakes (75%), with the remainder sourced from groundwater (aquifers),

desalination plants, recycling (including groundwater replenishment) and stormwater harvesting.

Water scarcity may become

an increasing issue for urban water supplies in the future. For example, groundwater provides two-thirds of all water used in

urban Western Australia. However, winter

rainfall has declined 28% since 2000, with reduced groundwater recharge, while demand is increasing due to population growth.

This is prompting a focus on water-sensitive urban design and climate-resilient water sources, including

desalination in some areas. Perth, along

with other state capitals (Adelaide, Brisbane–Gold Coast, Melbourne and Sydney) now have large seawater desalination plants.

The quality of drinking

water in urban areas is usually high, but can be more variable in regional and

remote areas due to the presence of natural-occurring contaminants (such as nitrates and uranium) and more limited capacity

to treat the water. Water service provision in regional and remote

communities can

be more complex, and costly, due to poor water quality sources, water

distribution and treatment challenges, and fragmented arrangements for delivery

(p. 162).

Independent

audits have found that water service provision in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

communities often fails to meet the Australian Water Quality

Guidelines. Poor standards of water and wastewater services compound

historical hardships and reinforce disadvantage, can worsen

existing health issues and increase

risks of disease and infection. Infrastructure

Australia states ‘there is clear evidence that services in many … remote

communities do not meet United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6:

clean water and sanitation for all’ (p. 619).

Urban waterways, and their

associated ecosystems, also provide important habitat for native animal and

plant species as well as a myriad of recreational opportunities. The Australian

Labor Party (ALP) has committed $200 million to an Urban Rivers and Catchments Program that will provide community grants supporting wetland

restoration, naturalisation of riverbanks, and revegetation.

Water storage and irrigation schemes

With over 500 major water storages, several thousand small

storages, and in excess of 2 million farm dams (p. 21), Australia has the highest per capita

surface water storage capacity in the world. According to the Bureau of

Meteorology, the capacity of Australia’s accessible storage capacity is about

81,000 GL. At the end of May 2022, they were 69.3% full.

Water harvesting, storage

and distribution schemes have been central to urban and regional development in

Australia. While dams and associated irrigation schemes have increased water

availability, infrastructure and works interrupt natural flow regimes, waterscape

connectivity and the operation of aquatic ecosystem processes that require the

run of the river.

Water resources assessments have suggested that a combination of groundwater,

large dam and farm-scale water storages have the potential to support the

development of irrigable agriculture in some areas across Australia’s north.

However, large-scale developments face significant hurdles, including economic

viability, environment sustainability, and heritage concerns.

Over the last decade the

Australian Government has announced numerous initiatives to support regional

water infrastructure, including the:

In May 2020, the NWGF

replaced the NWIDF, with the $2 billion in unspent funding from the Loan Facility transferred

to the NWGF (p. 140). The Morrison

Government’s 2022–23 Budget

provides an additional $6.9 billion over 12 years for investments through the

NWGF (p. 147). This includes commitments for water infrastructure projects such

as the Hells Gate

and Urannah dams

in Queensland and the Dungowan Dam

in NSW. This brings total investment available under the NWGF to $8.9

billion.

The ALP’s Water for Australia plan includes re-establishing

a National Water Commission, supporting renewal of the National water

initiative, and broadening the National Water Grid Investment Framework (which

sets out how

investment from the NWGF will be targeted) to allow it to fund a wider

range of water supply projects (rather than only agriculture projects). The ALP has indicated water infrastructure projects

will only proceed if they provide value for money.

Murray-Darling Basin

The Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) covers an area of 1

million km², is home to more

than 40 First Nations, and hosts a wider population of 2.3 million

people. The MDB produces

food and fibre worth $22 billion and provides tourism services worth $11

billion each year. Two-thirds

of Australia’s irrigation water is used in the MDB. However, evaporation

rates in the MDB are high, with 94%

of rainfall used by plants or evaporating. The demand for water has

resulted in significant pressures on freshwater ecosystems and degradation

of water quality. Water storage levels across the MDB increased from 58% to 90% between May 2021 and

May 2022.

In January 2007, in the midst of the Millennium

drought, the Howard Government announced

a $10 billion National plan for water security to improve water

efficiency and address the over-allocation of water in rural Australia,

including in the MDB. In August 2007, the Australian Parliament passed the Water Act 2007

which establishes the legislative framework for managing water in the MDB in

the national interest and for providing information on Australia’s water

resources. The Basin states (Qld, NSW, Vic, ACT

and SA) subsequently referred limited powers to the Commonwealth to allow for new arrangements in the MDB to take

effect, including the establishment of the Murray-Darling

Basin Authority (MDBA).

The Basin Plan

The Water Act is

implemented through the Basin Plan 2012, which was legislated in November 2012 following a multi-year

negotiation process. The Basin Plan specifies the surface water and groundwater

long-term average sustainable diversion limits (SDL) for the entire MDB, as well as for each surface

water and groundwater unit and water resource plan area.

The SDLs are essentially

the maximum amount of water that can be extracted in a year. The original surface water SDL for the whole basin was set at

10,873 gigalitres per year (GL/y). In July 2018, the SDL was increased by 70

GL/y to 10,945 GL/y after the Northern

Basin review. The SDLs came into operation

on 1 July 2019, along with a mechanism for their adjustment.

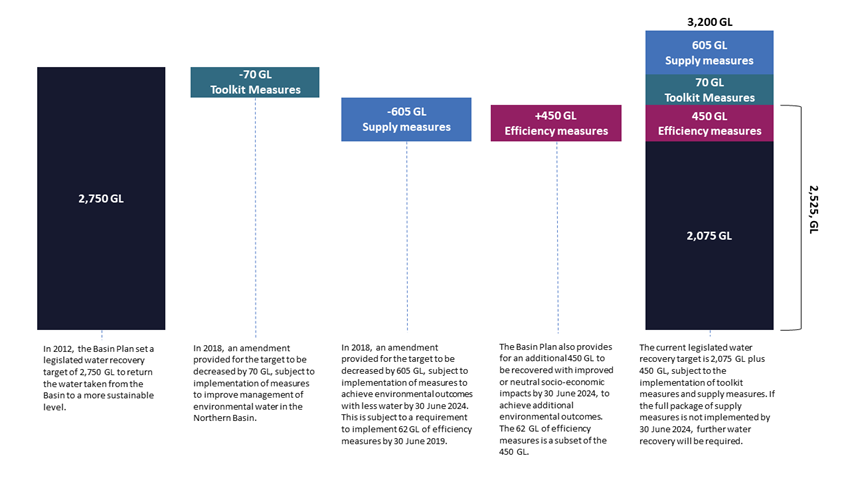

The establishment of the SDL was accompanied by the

setting of a water

recovery target of 2,750 GL/y (also referred to as the ‘bridging the gap’

target). This represented the gap between the water being used prior to

implementation of the Basin Plan and the SDL.

Under the Basin Plan, the

Basin states manage water resources within their jurisdiction using their own respective

water legislation. States were required to prepare water resource plans (WRPs) for specific areas that are consistent with the Basin Plan and

relevant SDLs by 30 June 2019. WRPs set out how water will be used, how much water will be made

available for the environment, how water quality standards will be met, and how water resources will be managed in extreme dry periods.

The WRPs of all Basin states- other

than NSW- have been accredited by the MDBA. The MDBA and NSW have entered into a bilateral agreement to ensure that key elements of the Basin Plan are

implemented while NSW’s WRPs are being prepared. In June 2022, the

Inspector-General for Water Compliance (IGWC) argued

that the Commonwealth Water Minister should utilise ‘step-in powers’ in the

Water Act to ensure that NSW’s WRPs are completed as soon as possible. In

August 2021, the compliance and enforcement powers of the MDBA were transferred

to the IGWC. This followed numerous reviews, including the Five-year assessment

of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan (see Box 12.1 at p. 301), to assess water

management compliance across the Basin.

The Basin Plan also

provides for:

The Basin Plan will not be fully implemented until 30 June 2024, when the agreed constraints measures and ‘supply’ and ‘efficiency’ measures under the SDL

Adjustment Mechanism are completed.

Figure 2 Water

recovery under the Basin Plan

Source: Parliamentary Library adaptation

from Sally Farrier, Simon Lewis and Merran Kelsall, First Review of

the Water for the Environment Special Account, Report to the

Commonwealth Minister for Water Resources as required under Section 86AJ of the

Water Act 2007, (Canberra: Australian Government, March 2020), Figure 1,

10.

SDLs and water buybacks

The establishment of SDLs- at an environmentally sustainable level of water use or take- has

been one of the most contentious elements of the Basin Plan. The 2010 Guide

to the proposed Basin Plan considered that water recovery ‘needed to

ensure a sustainable level of take, is between 3,000 GL/y and 7,600 GL/y, on a

long-term average basis’ (Volume 2, p. 166). This became politically

untenable: South Australia argued for at least 3,200 GL/y to be recovered

as environmental water, while NSW and Victoria wanted less than 2,750 GL/y to

be recovered.

As a compromise, the Australian Government

established 2 mechanisms:

Australian Government funding is supporting 3 types

of measures or projects in the MDB. Supply

measures deliver water for the environment more efficiently so less water

is needed. Efficiency

projects change water practices, such as improved irrigation methods, and

save water for the environment. Constraints

projects overcome some of the physical barriers that impact water delivery.

In January 2018, the Basin Plan was amended to

provide for the implementation

of supply projects to allow 605 GL/y of additional water to remain

available in the system (altering the water recovery target to 2,075 GL/y),

while still achieving the same or better environmental outcomes. This was

dependent on the recovery of a minimum of 62 GL/y through efficiency

projects by 30 June 2019. The

62 GL/y is a subset of the larger 450 GL/y target.

Progress on water recovery

Substantial progress towards

water recovery targets has been made, however, as at 30 April 2022, there was

a

significant shortfall in the recovery of water for the environment. Only 2

GL of the required 450 GL/y water

recovery for enhanced environmental outcomes has been delivered, although

23.9 GL/y has been contracted.

The MDBA’s annual

progress reports for the SDL Adjustment Mechanism and the First review of

the water for the environment special account indicate that it is

unlikely the full amount of 450 GL will be recovered by 30 June 2024, putting

the overall SDL adjustment at risk. The Water Act makes provision for

the MDBA to

recalculate (reconcile) an appropriate adjustment amount and prepare an

amendment to the Basin Plan in these circumstances. The Australian Government would

then need to consider the best options for bridging the water recovery gap to

ensure the outcomes of the Basin Plan are achieved.

The Australian Government initially purchased water

entitlements directly from landholders (‘buybacks’) to support the achievement

of the 2,075 GL/y water recovery target; 1,227 GL had been

purchased by the Commonwealth at a cost of $2.7 billion by October 2017 (p.

4). In September

2015, the Water Act was amended to cap the volume of water that

can be purchased at 1,500 GL (subject to exceptions). The relevant provisions

will cease

to operate when the first 10-year review of the Basin Plan is completed (p.

7). In September 2020, the Morrison Government ruled

out further buybacks; however, a substantial

shortfall in water recovery raises the prospect that the targets will not be met

by 2024 and further action will be required.

Policy commitments

The Morrison Government

had committed to delivering the Basin Plan in full, including the 450 GL

water for the environment. However, in July 2021, National

Party senators attempted to move amendments to the Water Act that would have removed a requirement to deliver the

450 GL of water for the environment, prohibited further water buybacks,

and extended the deadline for delivery of water recovery projects.

The incoming Albanese

Government’s Water for Australia plan includes a ‘five-point plan to safeguard the Murray-Darling

Basin’. This includes:

- delivering on water

commitments- including the 450 GL for environmental water

- increasing compliance,

and improving metering and monitoring

-

restoring transparency,

integrity and confidence in water markets and water management

- increasing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' ownership and involvement in decision-making, including delivering the $40 million of cultural water

-

updating the science,

including data on climate change, evaporation and inflows.

Further reading

Infrastructure Australia, An Assessment of Australia’s Future Infrastructure Needs- The Australian Infrastructure Audit, (Infrastructure Australia, 2019).

Productivity Commission, Murray-Darling Basin Plan: Five-Year Assessment, Inquiry Report no. 90, (Canberra: Productivity Commission, 19 December 2018).

Productivity Commission, National Water Reform 2020, Inquiry Report no. 96, (Canberra: Productivity Commission, 28 May 2021).

Back to Parliamentary Library Briefing Book

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.