Nuttall’s now lesser-known monotone painting was unveiled on 19 June 1902 and sent to Paris to be reproduced in photogravure. Copies of Nuttall’s work, featuring 344 identifiable ‘heads’ were hung in homes, lobbies and state schools throughout the country.17

Nuttall, a popular illustrator, was also commissioned by a Melbourne business syndicate, the Historical Picture Association, to capture in detail the grand opening.

In line with the brief to represent as many recognisable ‘heads’ as possible, Nuttall managed to capture 344 portraits of various dignitaries, many of which involved private sittings so that the artist could make his preparatory sketches. A further challenge was the inclusion of as many dignitaries as possible, hence Nuttall’s arrangement of parliamentarians in curved, rather than straight rows.

Shortly after its completion in 1902, the painting was sent to Paris and a large photogravure edition made by the well-known firm Goupil & Cie. The image was sold with the slogan ‘No Australian Home will be complete without a Copy’. In the first half of the 20th century, the popular print hung in many homes and public buildings across Australia. However, as time passed, its popularity declined, and the Tom Roberts version of the opening became the symbolic image of Federation.18

The first federal election and composition of the Parliament

Australia’s first federal election on 29 and 30 March 1901 returned 75 members to the House of Representatives and 36 members to the Senate. As there was no federal electoral Act, the election took place as six separate elections, held according to each state’s own legislation ‘for the more numerous House of the Parliament’.19 This led to significant differences in electoral procedure and franchise across the new nation.

Neither enrolment nor voting was compulsory, with the latter introduced federally in 1924.20 Of Australia’s population of some 3.7 million, only around 988,000 people were enrolled to vote; of these, only 56.7 per cent cast their ballot for the House of Representatives.21

Six lower House seats had candidates elected unopposed, including three members of the first government ministry. In contrast, SA saw 17 candidates stand in its single electorate ballot, with the top seven candidates elected. Tasmania was also defined as a single electorate, with five of its nine candidates duly elected. While women were eligible to stand for election in SA and WA (having had the franchise since 1895 and 1899 respectively), none did.22

One hundred and eighty-one candidates stood for the House of Representatives, and 127 in the Senate.23 Party structures were embryonic, and selection processes were many and varied.24 Most candidates were associated with one of three loose political groupings: the Protectionists, the Free Traders, and Labor. However, few voters were faced with a choice of three parties in the House of Representatives elections. Of the 63 single-member electorates, there were only seven in which all three parties fielded candidates.25

None of the three parties won a necessary majority. Barton and the Protectionists held 33 seats, so his minority Government relied upon the support of Labor members. George Reid and the Free Traders formed the official Opposition. The 1901 election set the pattern for the Commonwealth Parliament’s first decade, with minority governments continuing until the Labor Party secured 42 of the 75 seats in 1910.

Of the 111 Commonwealth parliamentarians elected in 1901, 87 (78 per cent) had previously served in a colonial parliament: 29 of the 36 senators (81 per cent) and 58 of the 75 members (77 per cent). John Forrest26, Frederick Holder27, William Lyne and George Turner28 had all been sitting Premiers, while another 10 had previously served in such a role.29

Just over half of the first Parliament were Australian born; of the rest, all but four were born in the UK or Ireland.30 The average age was 48, with the youngest being Tasmanian Senator John Keating31 at 28 years of age, and 71-year-old Member for Tasmania Edward Braddon32 the oldest. Forty-one per cent were educated overseas, a little over a third were known to have been tertiary educated, and three per cent had no formal schooling at all.33 In terms of their occupations, 44 per cent were professionals, 25 per cent had worked in commerce/business, 19 per cent were tradesmen, five per cent were primary producers and two per cent were union or party officials.34

Notable among the members was William Groom, elected to the House of Representatives after a long career in the Queensland Legislative Assembly.35 Groom was a tangible link between the new nation and its convict origins, having been transported from England to Australia in 1849 for stealing.36 Groom died in August 1901. His son, Littleton Groom, was elected in his place in the first Commonwealth by-election on 14 September 1901.

Although overseas during the campaign, John Ferguson was elected to represent Queensland in the Senate. (At the time, he was also a member of the Queensland Legislative Council.) Ferguson’s Senate seat was declared vacant on 6 October 1903 owing to his two-month absence without leave. He remains the only senator to lose his seat in this manner.37 The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1902 (section 96) would prevent such dual representation by prohibiting current members of state parliaments nominating for federal Parliament.

Not until Stanley Bruce in 1923 would Australia have a Prime Minister who had not first served at colonial/state level and in the first federal Parliament.38

Swiss Studios Melbourne, Members of the first Parliament 1901, 1901, Official Gifts Collection, Parliament House Art Collection.

The portraits of the individual members of the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia were produced in May 1901 during the first sitting of Parliament in Melbourne. Taken by Swiss Studios it comprises individual portrait studies of each parliamentarian, plus the Governor-General Lord Hopetoun located in the centre.

Commemorative sitting of federal Parliament at the Royal Exhibition Building

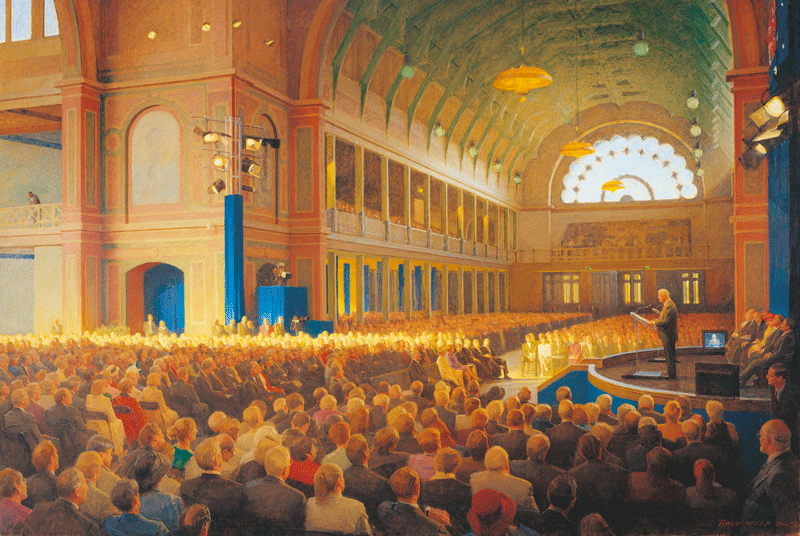

In 2001, Australia celebrated the centenary of Federation. On 9 May, a commemorative sitting of the federal Parliament was held in Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building. The 7,000 attendees included federal, state and territory parliamentarians, the full diplomatic corps, and representatives from ‘every sector of Australian society’.39 Proceedings were led by Governor-General Sir William Deane, Prime Minister John Howard, and Leader of the Opposition Kim Beazley. It was followed by a ceremony featuring performances, speeches and awards for outstanding achievement.40 Speakers included former Olympian Betty Cuthbert, supported by fellow athlete Nova Peris, and 15-year-old Hayley Eves, chosen to represent Australian youth. In advocating for Australian republicanism, greater political representation of women, and multiculturalism, Hayley’s speech was celebrated by observers.

Robert Hannaford (born 1944), Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sitting of federal Parliament, Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne, 9 May 2001, 2003, Historic Memorials Collection, Parliament House Art Collection.

The painting, commissioned to document the Parliament’s commemorative sitting for the Centenary of Australia’s Federation in 2001, was intended to be a companion piece to Tom Roberts’s ‘Big Picture’. Robert Hannaford was selected to undertake this commission with the Historic Memorials Committee proposing that the completed work be displayed alongside the ‘Big Picture’. It was not intended that the artist ‘be obliged to produce a modern equivalent of Roberts’ painting’ but ‘an agreed list of minimum inclusions’ was supplied by the Committee to ensure that he included recognisable likenesses of all 219 federal parliamentarians in attendance, as well as senior members of the official party.

Hannaford finished the study for the painting in 2001. In 2002, to fulfil the commission’s requirements, Hannaford painted some 77 individual portraits in Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, and Australian Parliament House, Canberra, where a makeshift studio was set up for him in the Senate Spouses’ Lounge. During a sitting week the artist completed around 17 portraits a day, with each portrait the result of a short 15-minute sitting. The final painting, similar in size and proportions to the ‘Big Picture’, was completed in 2003.

References

1. ‘George V (r. 1910–1936)’ Royal Family, accessed 9 July 2021.

2. ‘Edward VII (r. 1901–1910)’, Royal Family, accessed 9 July 2021.

3. D Saunders, ‘Reed, Joseph (1823–1890)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed 9 July 2021.

4. ‘Research Guides: Melbourne International Exhibition 1880–81’, State Library of Victoria, accessed 9 July 2021.

5. ‘The Commonwealth of Australia’, The Argus, 10 May 1901, p. 5, accessed 9 July 2021.

6. ‘Opening of the Commonwealth Parliament’, The Argus, 10 May 1901, p. 7, accessed 6 July 2021.

7. His Royal Highness the Duke of Cornwall and York, His Majesty’s High Commissioner, ‘Opening of parliament’, JN Dunn letter to Alfred Deakin, NLA MS 1540/ item 7/12–13.

8. M Kerley, ‘Baker, Sir Richard Chaffey (1841–1911)’, The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate Online Edition, Department of the Senate, Parliament of Australia, published first in hardcopy 2000, accessed 9 July 2021.

9. H Manning, ‘Holder, Sir Frederick William (1850–1909)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 2021, accessed 9 July 2021.

10. ‘Museums Victoria Collections: Item MM 54388’, Museums Victoria, accessed 21 October 2021.

11. V Isaacs, ‘Parliament in Exile’, Australian Parliamentary Review, Autumn 2002, vol. 17(1), pp. 79–96.

12. Isaacs, op. cit.; M Rutledge, ‘Barton, Sir Edmund (Toby) (1849–1920)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1979; R Norris, ‘Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981. Websites accessed 12 July 2021.

13. H Topliss, ‘Roberts, Thomas William (Tom) (1856–1931)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1988, accessed 9 July 2021.

14. S Palmer, ‘Nuttall, James Charles (1872–1934)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed 9 July 2021.

15. Tom Roberts, ‘The Big Picture: Icon of Federation’, Parliament of Victoria, accessed 24 July 2021.

16. A McCulloch, The Golden Age of Australian Painting: Impressionism and the Heidelberg School, Landsdowne Press, Sydney, 1969; R Russell and P Chubb, One Destiny: the Federation Story – How Australia Became a Nation, Penguin Books, Ringwood, Vic, 1998; K Scroope, ‘Faithful Representations: 100 Years of the Historic Memorials Collection’; A Mackenzie, ‘In the Artist’s Footsteps’. Websites accessed 5 August 2021.

17. ‘Painting – “The Opening, Commonwealth Parliament”, Charles Nuttall, Oil, 1901–1902’, Museums Victoria Collections, accessed 24 July 2021.

18. Palmer, op. cit.; ‘Painting – The Opening’, op. cit.

19. ‘Commonwealth of Australia Constitution’, section 31; M Simms, ‘Election Days: Overview of the 1901 election’, in M Simms, ed., 1901: The forgotten election, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 2001, pp. 28–31; ‘1901: The forgotten election’, Papers on Parliament, 37, Department of the Senate, November 2001. Websites accessed 27 July 2021.

20. M Healy and J Warden, ‘Compulsory Voting’, Research Paper series, 1994–95, no. 24, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, accessed 27 July 2021.

21. S Barber, ‘Federal election results 1901-2016’, Research Paper, Research Paper Series 2016-17, Parliamentary Library, 31 March 2017, pp. 16 and 61; Australian Electoral Commission, ‘Voter turnout – previous events’, AEC, accessed 24 July 2021.

22. G Souter, ibid p. 33.

23. Ibid., p. 31.

24. Simms, op. cit., p. 6.

25. Rydon, ‘Electorial Methods’, in Simms, 1901: The forgotten election, op. cit., p. 26.

26. F Crowley, ‘Forrest, Sir John (1847–1918)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed 9 July 2021.

27. H Manning, ‘Holder, Sir Frederick William (1850–1909)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 2021, accessed 1 December 2021.

28. G Serle, ‘Turner, Sir George (1851–1916)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1990, accessed 9 July 2021.

29. Those who had previously served in colonial parliaments were: Richard Baker; John Barrett; Edmund Barton; Egerton Batchelor; Robert Best; Edward Braddon; Thomas Brown; Donald Cameron; John Chanter; Austin Chapman; David Charleston; Francis Clarke; James Cook; Joseph Cook; Samuel Cooke; George Cruickshank; Andrew Dawson; Alfred Deakin; Henry Dobson; John Downer; James Drake; Norman Ewing; Thomas Ewing; John Ferguson; Andrew Fisher; John Forrest; Simon Fraser; George Fuller; Philip Fysh; Thomas Glassey; Patrick Glynn; Albert Gould; Arthur Groom; William Groom; Robert Harper; William Hartnoll; Henry Higgins; William Higgs; Frederick Holder; William (Billy) Hughes; Isaac Isaacs; Thomas Kennedy; Charles Kingston; William Knox; William Lyne; Thomas MacDonald-Paterson; James McCay; James McColl; Charles McDonald; Gregor McGregor; , Charles MacKellar; Allan McLean; Francis McLean; William McMillan; Alexander Matheson; Samuel Mauger; Edward Millen; John Neild; Richard O’Connor; King O’Malley; Pharez Phillips; Frederick Piesse; Thomas Playford; Alexander Poynton; Edward Pulsford; John Quick; George Reid; Charles Salmon; Frederick Sargood; Henry Saunders; William Sawers; Arthur Smith; Sydney Smith; Elias Solomon; Vaiben Solomon; William Spence; James Stewart; James Styles; Josiah Symon; Josiah Thomas; Dugald Thomson; George Turner; David Watkins; John (Chris) Watson; James Wilkinson; William Wilks; William Zeal.

30. Department of the Senate, ‘For peace, order and good government – The first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia: members of the first Parliament’, Department of the Senate. The four were: James Cook (NZ), Simon Fraser (Canada), Chris Watson (Chile), and King O’Malley (USA). See IR Hancock, ‘Cook, James Newton Haxton Hume (1866–1942)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1981; EM Redmond, ‘Fraser, Sir Simon (1832–1919)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1972; B Nairn, ‘Watson, John Christian (Chris) (1867–1941)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1990; A Hoyle, ‘O’Malley, King (1858–1953)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1988. Websites accessed 1 December 2021.

30. Q Beresford, ‘Keating, John Henry (1872–1940)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed 27 July 2021.

31. Bennett, ‘Braddon, Sir Edward Nicholas Coventry (1829–1904)’, op. cit.

32. J Rydon, A federal legislature: the Australian Commonwealth Parliament, 1901–1980, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp. 146–47.

33. Ibid., p. 168.

34. DB Waterson, ‘Groom, William Henry (1833–1901)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1972, accessed 6 December 2021.

35. ML Simpson, From convict to politician, Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2014.

36. D Carment, ‘Groom, Sir Littleton Ernest (1867–1936)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed July 2021.

37. ‘Ferguson, John (1830–1906)’, The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, online edition, accessed 1 December 2021.

38. H Radi, ‘Bruce, Stanley Melbourne (1883–1967)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed 9 July 2021.

39. Centenary of Federation Victoria, Victoria Celebrates, 2001, p. 35.

40. Centenary of Federation Victoria, A Nation United – 9 May 2001, 2001; Centenary of Federation Victoria, Victoria Celebrates, 2001.