Introduction

Establishment

1.1

On 11 October 2016, the Senate established the Select Committee on Red

Tape (committee) to inquire into and report on the effect of restrictions and

prohibitions on business (red tape) on the economy and community, by 1 December

2017, with particular reference to:

- the

effects on compliance costs (in hours and money), economic output, employment

and government revenue, with particular attention to industries, such as

mining, manufacturing, tourism and agriculture, and small business;

- any

specific areas of red tape that are particularly burdensome, complex, redundant

or duplicated across jurisdictions;

- the

impact on health, safety and economic opportunity, particularly for the

low-skilled and disadvantaged;

- the

effectiveness of the Abbott, Turnbull and previous governments' efforts to

reduce red tape;

- the

adequacy of current institutional structures (such as Regulation Impact

Statements, the Office of Best Practice Regulation and red tape repeal days)

for achieving genuine and permanent reductions to red tape;

- alternative

institutional arrangements to reduce red tape, including providing subsidies or

tax concessions to businesses to achieve outcomes currently achieved through

regulation;

- how

different jurisdictions in Australia and internationally have attempted to

reduce red tape; and

- any

related matters.[1]

1.2

On 28 November 2017, the Senate extended the reporting date to 3

December 2018.[2]

1.3

The committee decided to conduct its inquiry by focusing on specific

areas. This interim report presents the committee's findings and conclusions

about the effect of red tape on health services (health services inquiry).

Conduct of the health services inquiry and acknowledgement

1.4

The committee advertised the health services inquiry on its website and

wrote to a number of organisations, inviting submissions by 22 January 2018. The committee

continued to accept submissions received after this date. In total, the committee

received 11 submissions, which are listed at Appendix 1.

1.5

The committee held a public hearing in Canberra on 9 February 2018. The witnesses

who appeared before the committee are listed at Appendix 2.

1.6

The committee thanks the organisations who made submissions and who gave

evidence to assist the committee with its health services inquiry.

Scope of the report

1.7

Chapter one provides broad background information to set the regulatory

context for the health services inquiry. Chapter two then examines some of the information

presented to the committee, which may be drawn upon in the committee's final

report.

Regulatory framework for health services

1.8

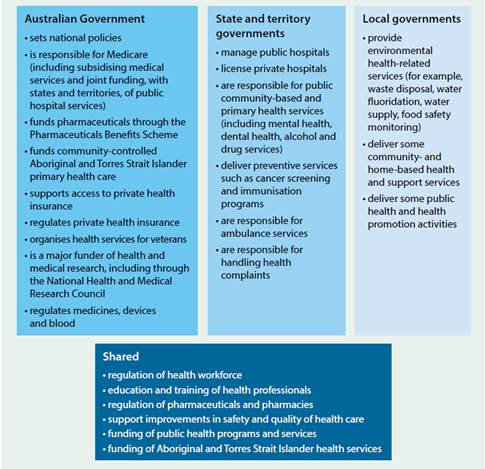

The health services inquiry encompasses Commonwealth, state, territory

and local government responsibilities. Accordingly, there are a number of

regulatory regimes upon which submitters and witnesses could comment. In this

report, the committee focussed primarily upon Commonwealth responsibilities.

Figure 1 illustrates the responsibilities of each level of government.

Figure 1.1: Government responsibilities, Australian

health system

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare,

Australia's Health 2016, 2016, p. 24.

Australian Government responsibilities

1.9

The Department of Health (Department) has a diverse range of

responsibilities which reflect a common purpose—better health and ageing

outcomes for all Australians.[3]

In total there are 10 outcomes including: access to medical and dental services;

primary health care; private health; and health infrastructure, regulation,

safety and quality. Specific agencies—such as the Australian Commission on

Safety and Quality in Health Care and the National Health and Medical Research

Council—are responsible for a further 20 outcomes in the Health portfolio.[4]

Regulatory Reform Agenda

1.10

In 2013, the Australian Government introduced the Regulatory Reform

Agenda (Agenda): to reduce the burden of regulation across government;

to coordinate red tape reduction efforts; and to set clear expectations

that regulation should not be the default option for government policy makers.[5]

1.11

Key elements of the Agenda include:

-

cutting regulatory compliance costs to businesses, community

organisations and individuals by at least $1 billion a year;

-

requiring all major regulatory decisions to be informed by a Regulation

Impact Statement (RIS) that sets out the benefits/costs of regulation;

-

introducing the Regulatory Burden Measurement framework to

calculate the regulatory costs of current/proposed policies or regulation;

-

undertaking an assessment of the regulatory burden imposed by the

Commonwealth stock of regulation; and

-

introducing the Regulator Performance Framework for over 80

regulatory authorities, to encourage regulators to:

-

reduce regulatory burden;

-

communicate clearly with stakeholders;

-

take risk‑based and proportionate approaches to regulation;

-

operate efficiently and transparently; and

-

undertake continuous improvement.[6]

Performance under the Regulatory

Reform Agenda

1.12

By 31 December 2015, the Australian Government reported having made

decisions to reduce regulation compliance costs by $4.8 billion.[7]

Of this total, the Department reported it had achieved net savings of $249

million, with significant reductions in red tape, notwithstanding the

introduction of new regulation.[8]

1.13

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PMC), which is

responsible for coordinating the regulatory policy priorities across all

portfolios, has not published up‑to-date information for 2016, 2017

or 2018.[9]

The Department was not able to advise its regulatory savings since 2015, instead

referring the committee to PMC.[10]

1.14

In addition to regulatory savings, the Department advised that it

continually tests the relevance and effectiveness of existing regulation, and

explores opportunities to reduce red tape.[11]

A major deregulatory measure was the 2015 Review of Medicines and

Medical Devices Regulation. This review focussed on the regulatory

framework and processes of the Therapeutic Goods Administration.[12]

1.15

As part of best practice regulation, the Department also conducts

regulatory impact analysis in the form of RISs.[13]

In 2014–2015, six statements were developed, however it is not clear from the

Department's website if any RISs have been developed since 2015.[14]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page