Chapter 5

Issues—governance

Instead of a “mental health system”...we have a collection

of often uncoordinated services that have accumulated spasmodically over time,

with no clarity of roles and responsibilities or strategic approach that is

reflected in practice.[1]

National Mental Health Commission

National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services

Introduction

5.1

The committee has heard much evidence about mental health issues over

the course of its 38 hearings. As a result, the committee agreed to hold three

hearings on mental health issues, with a key focus on the findings of the

National Mental Health Commission and the government's consideration of its

response.

5.2

At the committee's public hearings on 26 and 28 August, and 18 September

in Canberra, Sydney, and Brisbane respectively, the committee heard from a

diverse range of mental health groups, carers, consumers, service providers and

others, including the National Mental Health Commission and the Mental Health

Commissioners of Queensland and New South Wales.

5.3

This chapter sets out the issues raised with the committee during its

hearings, and in the submissions received from groups and individuals, in

relation to governance and funding in mental health service and programme

delivery. These issues include:

-

Fifth National Mental Health Plan;

-

Mental Health Service Planning Framework;

-

Outcomes focussed funding with reporting; and

-

Policy and funding uncertainty.

5.4

The committee has examined each of these issues from three perspectives:

the evidence it received from witnesses; the findings of the Commission; and,

where it exists, Government reaction to the Commission's findings. The

committee summarises its findings and makes its recommendation towards the end

of this chapter. Issues relating to delivery of services and programmes, and

the committee's recommendations, are in Chapter 6.

Fifth National Mental Health Plan

5.5

In the 2015-16 Budget, the Government committed to work in collaboration

with States and Territories to develop the fifth national mental health plan.[2]

5.6

The Fourth National Mental Health Plan set:

...an agenda for collaborative government action in mental

health for five years from 2009, offers a framework to develop a system of care

that is able to intervene early and provide integrated services across health

and social domains, and provides guidance to governments in considering future

funding priorities for mental health.[3]

5.7

The Fourth National Mental Health Plan was developed to guide reform and

actions as part of the implementation of the National Mental Health Policy,

which was endorsed by Australian Health Ministers in 2008.[4]

The National Mental Health Policy sits within the National Mental Health

Strategy, endorsed in April 1992 by the then Australian Health Ministers'

Conference as a framework to guide mental health reform.[5]

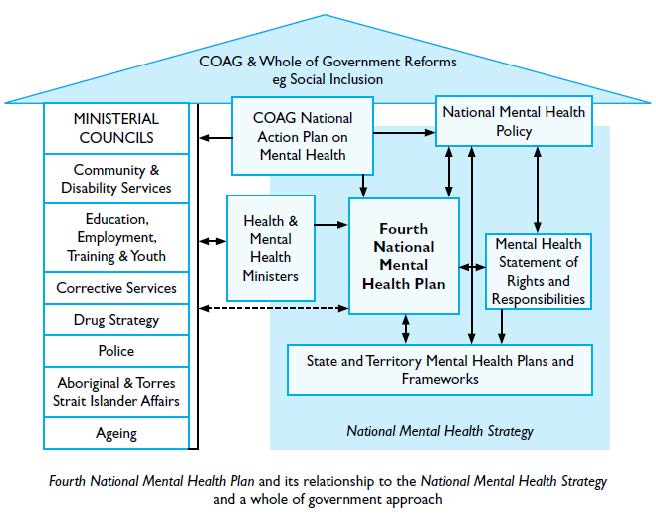

5.8

Figure 5 below shows the relationship of the Fourth National Mental

Health Plan to the National Mental Health Policy, the National Mental Health

Strategy, and the other elements of mental health within the COAG framework.

Figure 5—Fourth

National Mental Health Plan in context[6]

5.9

Mr Cormack told the committee that work on Fifth National Mental Health

Plan is in its early stages:

...the Fifth National Mental Health Plan was a decision taken

by the COAG health council to progress that work. It is really just in its

early stages. It has been assigned to be led by Tasmania under the Mental

Health and Drug and Alcohol Principal Committee of AHMAC [the Australian Health

Ministers' Advisory Council] auspices, and a working group has been established

to progress that work. Through the course of the development of the Fifth

National Mental Health Plan there will be extensive consultation with a wide

range of stakeholders within the Commonwealth and also within state and

territory governments, the NGO sector and the private sector. At this stage...I

think there have been two meetings of the working group. It is hitting its

straps, but it is certainly not into the level where they would be ready for

wide-scale consultation with the sector. That has always been the process for

previous national mental health plans. There is extensive consultation, and

that will be the case with the Fifth National Mental Health Plan.[7]

5.10

Witnesses generally felt that the development of the Fifth National

Mental Health Plan should be considered in light of the findings of the

Commission's review. For example, Mr David Meldrum, the Executive Director of

the Mental Illness Fellowship of Australia argued that to be successful the

Fifth National Mental Health plan needed accountability and evaluation

mechanisms:

The First National Mental Health Plan...had a little bit of

bite because of its newness and, in fact, it came out of a fair bit of argument

between people on which direction we should be heading. In that sense, it was

quite influential.

With the last couple [of five year mental health plans], in

my view, you have been able to read them and say, 'That's about right,' but

that is about the end of the conversation. There has been nobody made

accountable to do something about those, particularly in the Commonwealth-state

divide. You have mental-health plans in every state and territory being

developed, as we speak. They either have just been released or are about to be

released or are starting to be formulated. That is the situation at any given

time. Most of them are the same. Most of them do not have any sort of a

timetable or accountability for implementation. This one needs state ministers

and the Commonwealth minister and key departmental heads not only to be saying,

'This looks like the way mental-health services ought to look' but also 'It

contains some specific accountabilities for outcomes that will lead to some

implementation.'[8]

5.11

Professor Malcolm Hopwood, President of the Royal Australian and New

Zealand College of Psychiatrists maintained that the Fifth National Mental

Health Plan was an opportunity to organise the government's response to the

Commission's findings, in a way which included both a national and regional

perspective:

I would support the idea that, both at a regional level and a

national-plan level, a national mental-health plan is an opportunity to say:

'What are the kinds of elements that we really need in a service response that

are going to give us the best chance of solving these kinds of difficult

problems?' Of course, there are going to be local variables within that. One of

our challenges...is that we need a diverse sector to meet the needs of the people

we work with. But that can end up being confusing, difficult to approach and,

at times, more competitive than is helpful. A national mental-health plan is a

great opportunity for us to say a little bit more clearly how we want these

elements to fit together, how we are going to govern that niche region and

really tell if it is having the impact...We really want to make the best of that

opportunity.[9]

Mental Health Service Planning Framework

5.12

The National Mental Health Service Planning Framework (the Framework)

was an initiative of the Fourth National Mental Health Plan for:

...the development of a national service planning framework

that establishes targets for the mix and level of the full range of mental

health services, backed by innovative funding models.[10]

5.13

The aim of the Framework was to:

...better estimate service demand across the service spectrum

and across different care environments and will allow jurisdictions to identify

service areas requiring investment. This project will reform mental health

planning in both Australia and internationally and will provide the mental

health planning community with a solid tool from which to establish creative

resource solutions.[11]

5.14

The Framework was to be guided by the following principles:

-

Nationally consistent – The NMHSPF will provide an 'Australian

average' estimate of need, demand and resources for the range of agreed mental

health services required across the lifespan and across the continuum of care

from prevention to tertiary treatment.

-

Flexible and portable – The NMHSPF will be flexible to

jurisdictional adaptation, and will be presented in a user friendly format.

However, some technical aspects cannot be altered or the validity of the

product will be compromised.

-

Not all, but many – To ensure national viability, the NMHSPF will

not account for every circumstance or service possibly required by an

individual or group, but will allow for more detailed understanding of need for

mental health service across a range of service environments.

-

Not who, but what – The NMHSPF will capture the types of care

required, but will not define who is best placed to deliver the care. Decisions

about service provision will remain the responsibility of each state/ territory

and the Australian Government.

-

Evidence and expertise – The NMHSPF will identify what services

'should be' provided in a general mental health service system. Contemporary

mental health practice, epidemiological data and working with key stakeholders

with diverse expertise will underpin the technical, clinical and social support

mechanisms that will form the content of the framework.[12]

5.15

Consultation with a range of mental health sector stakeholders was built

into the Framework structure. The project was to be supported by an executive

group comprising of mental health representatives from all Australian

jurisdictions, and a modelling group with three expert groups:

-

Primary Care / Community / Non Hospital Expert Working Group

-

Psychiatric Disability Support, Rehabilitation and Recovery

Expert Working Group; and

-

Inpatient / Hospital Based Service Expert Working Group.[13]

5.16

The modelling group also included a consumer and carers reference group

and consumers and carers could participate through the three expert groups.[14]

5.17

Funding for the Framework was provided by the Commonwealth, through the

Department of Health and Ageing (now the Department of Health) and the project

was led by the NSW Ministry of Health in partnership with Queensland Health and

other jurisdictions. The timeframe for the project was two years, with the

project to be completed by 2013.[15]

5.18

Mr David Butt, CEO of the National Mental Health Commission told the committee

that when the Commission began its review, it requested a copy of the Framework

from the Department of Health, but it was not provided:

No, we were not [provided with a copy of the NMHSPF]. I think

we have commented previously that it would have been useful to have it, because

what it does is model the staffing and the services to respond to particular

assessed needs. So that would have been a very useful tool, and it probably is

a very useful tool. My understanding—and you really would need to check this

with the department again—is that it has been distributed across all the states

and territories and they are all looking at the implications and whether it is

in fact a good model...[16]

5.19

Mr Butt's understanding was that the Framework was still under consideration

by the federal and state governments:

I think some concern has been raised by some states—not all

states—that the potential implications of implementing that model would be

quite expensive, but the resourcing issue is a separate issue from the planning

tool, from our perspective. Governments have to make decisions about how much

investment they will put into particular services and obviously there are

finite resources available. So we would certainly be eager to see that services

planning framework finalised and released.[17]

5.20

Other witnesses told the committee that the Framework was eagerly

awaited by the mental health sector. Mr Quinlan, CEO of Mental Health Australia

advised that:

It is fair to say that those across the sector who invested a

lot of time—and it is true to say that there were some hundreds of people

across the sector—in developing that model [the NMHSPF] have been somewhat

frustrated by the fact that it has not yet managed to come out the other end of

the process. This is because it is likely to give us some of the answers to the

questions that David Meldrum [Executive Director, Mental Illness Fellowship of

Australia] alluded to—what are the numbers [of mental health consumers and

mental health services]?—and gives us a platform where we can have a sensible

debate about who is in what group and where the sorts of services for them

should rest.[18]

5.21

According to representatives of the Department of Health, the Framework

is still under development. Mr Cormack described the current situation relating

to the Framework as 'a collaborative piece of work that is being progressed

through the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council. It is well advanced.'[19]

5.22

Ms Janet Anderson, First Assistant Secretary of the Health Services

Division of the Department of Health expanded on Mr Cormack's answer:

...the framework exists now, but it is what is known as a beta

version. It has had some testing in several jurisdictions, including New South

Wales, WA and Queensland. The Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol Principal

Committee of AHMAC [the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council] has

agreed to establish a steering committee to take forward the framework into its

further and final stages of development. They are aware of a number of areas

where further work is required. It does need some further effort. Apparently

there are some technological bugs, which I do not presume to know much about,

but they also want to look more closely at some elements of the design model

such as the way the care packages are put together. There are further

considerations to be given to rural and remote residents in terms of mental

health and also to Indigenous communities, and at the far end of all of that

there is the need to seek state and territory sign-off to the framework in

order for it to be a genuinely national product.[20]

5.23

Ms Anderson explained that the 'beta version' was 'a testing model':

It is something which is recognised as not yet fully

developed but has enough of the moving parts to see how it might apply in real

life but in a piloted way. It is not currently being used as a planning model,

but it is being tested as if it could be used and to identify things that might

need further development. Indeed, that list which I partially rendered is still

being developed. There is still the need for further identification of the

issues to be worked on to move it from its current testing phase into a

framework which nine jurisdictions can agree to.[21]

5.24

Ms Anderson's understanding of the timeframe for progressing the

Framework to completion was that approximately another year would be required:

My understanding is that the expectation of the time frame is

that it will take at least 11 or 12 months—probably to the middle of the next

calendar year—before this work is completed. A steering committee is being

established that is chaired by the Commonwealth and has representation from a

number of jurisdictions. It has not yet met, and I think its first meeting will

be in September. There is work now underway to establish its specific terms of

reference and a work plan which will guide its efforts over the coming 12

months.[22]

5.25

The fact that the Framework was in 'beta version' was the Department's

reason for the framework not being provided to the Commission during its

review. Mr Cormack argued that:

[The Framework] is a Commonwealth/state piece of work. It

obviously has very significant implications for the way services are planned,

designed, delivered and resourced. Any endeavour that requires collaboration

across the Commonwealth, state and territory governments on matters that would

potentially require changes or increases in their levels of resourcing do

require a significant degree of scrutiny within the budget processes of nine

jurisdictions. Accordingly, there are appropriate safeguards on the release of

unfinished, unapproved work. So it is not unusual for something that is in its

development stage within this governance context not to be made more broadly

available, particularly as it is subject to change. Whatever version they might

have been access at that point in time may not even have been the beta version;

it may have been an earlier version. Clearly, things have moved on.[23]

5.26

Although the Framework is being progressed towards completion, the

committee notes that there is limited publicly available information about this

fact. The committee gained information about the progress of the Framework

through its public hearing on 26 August 2015. The Department of Health's

website, which provides information about the Fourth National Mental Health

Plan, does not mention the Framework, its history or its current progress.

Information about Framework, which does not include its current status, is only

available through the National Library of Australia, Australian Government Web

Archive.

Outcomes focussed funding with reporting

5.27

It was the Commission's view that 'much of the funding from the

Commonwealth is neither particularly effective nor efficient.'[24]

Professor Fels told the committee:

Eighty-seven and a half per cent of the spending is downstream

on income support and crisis response, basically—the Disability Support

Pension, carer's payments, payments to states for hospitals, Medicare and

pharmaceutical benefits. So, much of the Commonwealth spending is for failure

to treat the problems early and cost effectively. It is payment for failure. We

have made recommendations about how that heavy expenditure could be reduced

with a much greater emphasis on and investment in prevention, early detection,

recovery for mental ill health and the prevention of suicide.[25]

5.28

Ms Jacqueline Crowe, a National Mental Health Commissioner observed that

without the proper identification of outcomes, and monitoring of those

outcomes, mental health funding could not properly benefit those with mental

ill-health:

...the key to all change initiatives is to ensure that change

means we do better—and we must do better for the people who are caring and our

families. To do this, Australia must consistently and rigorously be monitoring

and reporting publicly on outcomes. We do not currently do that well—and not

just outputs but outcomes for people, which includes human rights issues, the

effectiveness and quality of services, service system impacts, immigration,

performance and coordination, the reform process and, importantly, what people,

families and communities think of those systems.[26]

5.29

Ms Jaelea Skehan, the Director of the Hunter Institute of Mental Health

told the committee that a further impediment on the effectiveness of funding

for mental health was the current government funding being provided on a

year-by-year basis. Ms Skehan pointed out that this situation meant that early

intervention, prevention and health promotion was effectively de-prioritised:

...around funding, apart from the fact that prevention and

promotion is deprioritised compared to the more costly treatment ends of the

funding cycle,...I would really like to see some transparency about how funding

decisions are made, particularly in certain areas. We have seen a reduction in

funding in some areas and an increase in funding in others, and I am not sure

that there is a vision statement or a clear plan that makes it really clear to

the sector why certain priorities were made.[27]

5.30

Professor Hopwood, the President of the Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Psychiatrists outlined a further funding and outcomes issue. He

argued that no future work could be planned without first setting in place

mechanisms for targeted research:

...a really important element of any development in the mental

health sphere is research to improve what we do. The risk that we continue to

do what we do because we do it will be obviated if we measure the outcome

better, but common sense says we would still like to improve on what we can do.

So the very best we can do at the minute still could do with a lot of

improvement. A significant commitment for research is an important factor—and

that includes funding we currently receive from organisations like the NHMRC

while a specific allocation from potential new funds like the medical research

fund would be something we would like to support.[28]

Policy and funding uncertainty

5.31

As mentioned briefly in Chapter 4, mental health policy and funding has

been 'on hold'[29]

since February 2014 when the Government tasked the Commission to review of

mental health services and programme delivery.

5.32

While the Government has deferred major policy decisions until after the

review was completed, and subsequently on completion of the outcome of the ERG

and COAG processes (paragraph 4.22 Chapter 4), recent Budgets have made cuts to

mental health service funding.

5.33

The 2014-15 Budget included a $53.8 million cut to the Partners in

Recovery programme. The Budget also introduced the $7 GP co-payment,

much-criticised for creating a barrier to those seeking to access primary

health care, including mental health care.[30]

5.34

The 2015-16 Budget included 'savings' of $962.8 million to be achieved

over five years by 'rationalising and streamlining' funding across the Flexible

Funds, which include funding for mental health, drug and alcohol dependency and

preventative health services and programmes.[31]

5.35

Minister Ley's April 2015 announcement of additional funding of

$300 million to mental health services has gone some way to temporarily

ameliorating the problem. However, as the funding extension is for a 12 month

period, it is at best a stop‑gap measure.[32]

5.36

The mental health sector is waiting for the Government response to the

Commission's recommendations for sector-wide reform. In the meantime, the

uncertainty about future direction and funding means that the sector is facing

a crisis.

5.37

In addition to the funding crisis, the mental health sector is waiting

to see how the government's response to the Commission's recommendations will

link with the transition of mental health programmes to the NDIS. The NDIS

transition will be examined in Chapter 7, while this section focuses on the

uncertainty caused by the delay in Government decision making.

5.38

Witnesses told the committee of the difficulties of operating services

and programmes in the current uncertain environment. Mr Ivan Frkovic, the Deputy

Chief Executive Officer, National Operations of Aftercare told the committee

that mental health service clients were greatly concerned about the

continuation of existing services:

People are really concerned that existing services, such as

Personal Helpers and Mentors and Partners in Recovery, which are helping them

to maintain lives in the community to some level and degree, will disappear... This

is creating uncertainty at the moment and increasing anxiety and levels of

relapse amongst people, because they do not know, as I think has been said. A

lot of these programs are due to finish in June next year: 'What happens beyond

June? Where do I go?' So, it is creating problems for the participants

themselves—the individual consumers—families and carers. They are saying, 'What

do we do in this situation?'[33]

5.39

Ms Ka Ki Ng,

Senior Policy Officer, Mental Health and Wellbeing Consumer Advisory Group

BEING, explained that from the point of view of consumers and carers, the uncertainty

around policy and funding may have resulted in service disruptions:

We want to particularly highlight some of the recent

proposals and changes that have happened that may have caused some disruptions

to mental health service provisions which have had a flow-on impact on mental

health consumers as well as family and carers. For example, we are aware that

at the moment there are a lot of uncertainties within the community or

non-government mental health services sector. We know that things like the national

review into mental health programs and services have caused a lot of anxiety in

the sector with rumours of our services potentially being defunded or having

their budget reduced or possibly being severely restructured.

We have heard that the transition from Medicare Locals to

Primary Health Networks has not been a particularly smooth transition in some

areas and has led to loss of services or at least disruptions. There are

funding uncertainties with regard to ATAPS, Partners in Recovery and also the NDIS

rollout—what services may be available to mental health consumers who are not

going to be eligible for the scheme. All of these are snowballing into a big

mass of uncertainty that is impacting on the wellbeing of the people working in

the sector as well the people that are actually trying to access support and

services.[34]

5.40

In particular Ms Ng observed that the change from the Medicare Locals to

the PHNs had resulted in loss of staff and relationships between consumers and

health care professionals:

For example, people not being referred on by GPs because GPs

are not sure where to go to, not knowing whether that particular Medicare Local

in their region is going to survive. There is also loss of staff. Often what we

have found in the mental health sector, and I would imagine it is the same in

many other human services sectors, is that relationships are built between

individuals. I may have a really good relationship with a particular staff

member in the Medicare Local and I may not know many other people beyond that

relationship, or I may not have a lot of trust—it is a particularly profound

relationship for consumers and carers. If there is such an uncertain

environment at a service, what has been pointed out is that if there is staff

turnover, then people will naturally try to find alternatives and those

relationships are lost. For a GP it might be a case of, 'Okay, let's find

another relationship', but for consumers and carers, it might actually mean

that they have to consider whether they want to make the effort to build a

relationship again, especially if there have been previous relationships where

it was negative. It can be really traumatic. I think people mentioned some of

those issues this morning. [35]

5.41

As discussed above, the government's response to the concerns of

the mental health sector about the uncertainty around mental health policy is a

12 month funding extension. The government is considering advice from the ERG,

and other processes, before it will make its response to the Commission's

recommendations.[36]

Committee view

5.42

As noted in Chapter 4, the government received the Commission's

completed review in early December 2014. The government then delayed releasing

the review until mid-April 2015, when forced to do so when parts of the

Commission's report were leaked. In October 2015, ten months after the

completion of the Commission's review, the government has still not responded

to the Commission's recommendations. As a result, the mental health sector struggles

with ongoing funding uncertainty and indecision about the future direction of mental

health policy in Australia.

5.43

The committee heard the concerns of mental health groups, advocates,

service providers, and consumers and carers in relation to the uncertain future

direction of mental health funding and policy. These groups all gave the

committee similar evidence: the government needs to respond positively to the

Commission's recommendations and it needs to do so before the end of 2015.

5.44

The Commission's review has been delivered at a strategic time for the

implementation of change in funding and governance of mental health policy. A

number of complementary processes are currently in play:

-

the Fourth National Mental Health Plan expired in 2014 and work

is beginning on the Fifth National Mental Health Plan;

-

according to the Department of Health, the National Mental Health

Service Planning Framework has approximately one year of development remaining

before it is ready for release; and

-

with the PHNs newly established in July 2015, witnesses argued that

a further 12 months is needed for PHNs to become fully operational and

connected in their regions.

5.45

The committee believes that by making a response to the Commission's

review now, the government will set the mental health policy agenda for the

foreseeable future and provide much needed certainty for mental health groups,

service providers, carers, and consumers.

5.46

The Minister for Health has stated that the $300 million extension of

funding for mental health services and programmes provided in April 2015 will

provide 12 months for the government to develop its response to the

Commission's findings.

5.47

To provide much needed clarity to the mental health sector, the

committee urges the government to conclude its deliberations by the end of

2015. Mental health service and programme providers, carers, and consumers, are

keenly awaiting the government's future policy direction. State and territory

governments also await the government's response for their planning of the

Fifth National Mental Health Plan. And all stakeholders, including the

Commission, are awaiting the release of the National Mental Health Services Planning

Framework.

Recommendation 1

5.48

The committee recommends that the government:

-

immediately publish the Expert Reference Group report;

-

urgently respond to the National Mental Health Commission's

review; and

-

guarantee funding for mental health groups and service providers

for the 12 months after the announcement of the government response to the National

Mental Health Commission's review.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page