Assistance and support for veterans

Introduction

4.1

An area of unanimous agreement in this inquiry is the utmost importance

of individuals who are unwell being able to access appropriate support and

assistance. The role of both the Department of Defence (Defence) and the

Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) in offering and providing support and

assistance was a key focus in much of the evidence received by the committee.

4.2

The committee spoke with some veterans who were clearly in need of

immediate assistance and many of these individuals had been trying to access

support for some time. As noted earlier in the report, the committee was pleased

that representatives from DVA were in attendance at hearings and available to

provide assistance and support to individuals and families in immediate need if

they wished to speak with them.

4.3

This chapter discusses the matters raised with the committee in relation

to the provision of assistance to veterans, with particular reference to

assistance with their health concerns. It covers the actions taken to date by

Defence and DVA; veterans' experiences with accessing assistance; barriers to

accessing assistance; the assistance and support being sought; and addressing

veterans' concerns moving forward.

Summary of Government actions to date

4.4

As noted in Chapter 1, this committee tabled the report, titled Mental

health of Australian Defence Force members and veterans, on 17 March 2016. The

report included two recommendations in relation to mefloquine.[1]

4.5

Responding to the committee's recommendations from the report, on 15 September

2016, the Minister for Veterans' Affairs, the Hon Dan Tehan MP announced that

the government would:

-

establish a formal community consultation mechanism to provide an

open dialogue on issues concerning mefloquine between the Defence Links

Committee and the serving and ex-serving ADF community;

-

develop a more comprehensive online resource that will provide

information on antimalarial medications;

-

establish a dedicated DVA mefloquine support team to assist our

serving and ex-serving ADF community with mefloquine-related claims, which will

provide a specialised point of contact with DVA; and

-

direct the inter-departmental DVA-Defence Links Committee to

examine the issues raised, consider existing relevant medical evidence and

provide advice to the Government by November 2016.[2]

4.6

With particular reference to these actions identified by the Minister

for Veterans' Affairs, the committee asked witnesses at its public hearings in

Brisbane and Townsville for their perspective on the progress of

recommendations. While noting that witnesses would likely be unaware of the

DVA-Defence Links Committee action, it was disappointing to note that several

witnesses indicated they were completely unaware of the other actions.[3]

4.7

Following the hearing, Senator Alex Gallacher wrote to the Minister for

Veterans' Affairs, the Hon Darren Chester MP, seeking advice on the progress of

the announcements from the Government.

4.8

On 18 September 2018, the Minister wrote to the committee and included

the following update:

With respect to the commitments made by the then Minister for

Veterans' Affairs, the Hon Dan Tehan MP, I can advise these have either been

met or are ongoing. I draw the Committee's attention to the submission to the

inquiry from DVA which provides more information about services and supports

available to veterans and their families; and the future action plan involving

further outreach, communications and research in this area.[4]

4.9

While it is disappointing that there was little awareness of the response

to the recommendations within the community the actions were designed to assist,

the committee is aware that Defence and DVA have both undertaken a series of key

actions in response to the issues and concerns raised about antimalarial use

which are outlined below and throughout the chapter.

Department of Defence response

Key message

4.10

Defence has indicated that its response to concerns about the use of

antimalarial drugs has 'been designed to provide current and former serving

members with information about the medications of concern, detail on the

studies, and to encourage them to seek help'.[5]

A key message from Defence has been to encourage individuals with concerns to

consult their treating medical practitioner and to consider putting in a claim

with DVA.[6]

4.11

On 30 November 2015, Defence issued a statement on the use of mefloquine

in the ADF and advised that 'if any ADF member, past or present is concerned

that they might be suffering side-effects from the use of mefloquine defence

encourages them to raise their concerns with a medical practitioner so they may

receive a proper diagnosis and treatment'.[7]

Comprehensive website

4.12

In February 2016, VADM Griggs told the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence

and Trade Legislation Committee about the need for their actions to balance the

provision of information with the need to avoid causing undue concern for

people who are well:

I would like to make the point that we are now in about month

7 of a pretty sustained media campaign about mefloquine. What we have been

trying to do is to get out as much information as possible in as transparent a

manner as possible to allay the fears of serving and former serving members of

the ADF about the use of this drug, because the nature of the reporting and the

nature of this campaign has elevated concern levels amongst people who do not

need to be as concerned as they now are. We are actually quite concerned about

that. One of the things we have just completed is a series of web pages, which

is now available on the Defence internet site, which I think is a very

comprehensive and transparent articulation of all the issues around

antimalarials, not just mefloquine, in use in the ADF.[8]

4.13

In order to provide information to concerned veterans and their

families, Defence developed a comprehensive external website on malaria,

mefloquine and the ADF and established an email address where individuals can

request further information.[9]

Information for families

4.14

Defence advised that information for families concerned about

antimalarial use continues to be available by contacting the dedicated email

address as well as accessing information from their website.[10]

4.15

In its submission Defence also described other support services

available to families for a variety of reasons and not specifically related to

concerns about antimalarial use such as the ADF Family Health Program, the

All-hours Support Line, the Defence Family Helpline and the Veterans and

Veterans Families Counselling Service (VVCS).[11]

Research

4.16

To inform its ongoing response to these issues, Defence has undertaken

or commissioned research into a number of matters relating to its use of

antimalarials and in particular mefloquine, including:

-

a review of Medical Employment Classification outcomes of those

who participated in the Timor-Leste trials. This has shown no significant

differences in the incidence of becoming medically unfit for service, or

diagnosis of PTSD between those who were prescribed mefloquine and those

prescribed other anti-malarial medications;[12]

-

a comprehensive literature review on mefloquine commissioned from

Professor Sandy McFarlane AO, Director of the University of Adelaide Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies;[13]

and

-

commissioned (jointly with DVA) the University of Queensland to

undertake a research study involving the re-analysis of health study data on

anti-malarial use from the 2007-2008 Centre for Military and Veterans' Health

deployment health studies.[14]

Further information on this is outlined below.

Department of Veterans' Affairs

response

Mefloquine support team

4.17

In accordance with the government commitment announced in September

2016, DVA established a dedicated mefloquine support team within their claims

area to respond to inquiries about mefloquine. DVA advised the committee that

the team 'did not receive many calls' and that team was subsequently put onto

other duties within the claims area. In September 2018, DVA added information

to their phone line, prompting callers to dial zero to speak to someone in

relation to mefloquine but again they did not receive many calls.[15]

Support for GPs

4.18

DVA has provided information to general practitioners (GPs) to assist them

to provide support to veterans who may have concerns about mefloquine:

-

DVA's Principal Medical Adviser wrote to all GPs on 30 September

2016 and to the Primary Health Network in October 2016 to bring information about

mefloquine to their attention;[16]

and

-

DVA organised and hosted a briefing with GPs in Townsville on 29

November 2016.[17]

Information event

4.19

In December 2016, DVA held an event, referred to as an 'outreach program',[18]

in Townsville which was attended by more than 90 members of the community

concerned about antimalarial medications such as mefloquine. Defence supported this

event.[19]

As noted earlier, the government committed to establishing a formal community

consultation mechanism on issues concerning mefloquine and the Townsville 'outreach

program' was the first step.[20]

Support for families

4.20

DVA provides support to veterans' partners and families through funding

a range of health services as well as the front line mental health services

provided through Open Arms—Veterans and Families Counselling (formerly VVCS).[21]

DVA's Future Action Plan

4.21

In its submission, DVA noted it has 'prepared an action plan to address [veteran]

community concerns about potential effects of mefloquine that includes outreach

activities, communications and research'.[22]

Following the outreach program conducted in Townsville in December 2016 (in

collaboration with the Repatriation Medical Authority (RMA), VVCS and with the

support of Defence), DVA is conducting consultation forums across other capital

cities. The submission noted that these will be publicised through

advertisements in newspapers and services newspapers, as well as direct

invitations to relevant organisations, and individuals where possible.[23]

4.22

Ms Liz Cosson AO CSC, Secretary, DVA, provided further detail about

these consultation sessions at the hearing in Canberra. A series of sessions

were planned in different locations throughout October and November. Further

sessions in different locations would be considered should there be sufficient

demand.[24]

These consultation forums are further discussed later in the chapter.

DVA funded health treatment and

compensation claims

4.23

The support provided to veterans who have been injured or suffered

illness as a result of their service (including illness or injuries related to antimalarial

medication) fall broadly into three categories—compensation, income support and

health treatment. To access compensation and income support, a veteran needs to

make a claim and show to the relevant standard of proof that they have suffered

an illness or injury, and demonstrate that this condition was related to their

service.[25]

4.24

In relation to health treatment, there are two pathways by which

veterans may access DVA-funded services:

-

Under the non-liability pathway, veterans can apply for

access to treatment for mental health conditions without the need to show that

the condition is related to service.

-

Under the liability pathway, veterans can make a claim

which DVA will then assess to establish whether the condition was related to

service. If the claim is accepted, the veteran's entitlement to compensation

and income support will then be assessed, and the veteran will be eligible for

DVA-funded health treatment for the condition.[26]

4.25

In addition, all former serving personnel can access a comprehensive

health assessment from their GP.[27]

Independent of the claims process, mental health services are also available

from Open Arms—Veterans and Families Counselling to all current and former

serving personnel.[28]

4.26

Serving and ex-serving ADF members can claim compensation at any time

for medical conditions they believe are related to their service. For DVA to

accept liability for compensation there has to be a causal link determined

between the person's service and their medical conditions. Under the Veterans'

Entitlements Act 1986 (VEA) and the Military Rehabilitation and

Compensation Act 2004 (MRCA) the potential link between a medical condition

and service is assessed using Statements of Principles (SOPs).[29]

SOPs are discussed later in this chapter.

Veterans' experiences with accessing assistance

4.27

The committee explored with individuals their experiences of accessing

assistance; whether they had tried to access assistance, and if so, the details

of that experience. The committee also spoke to veterans who had not accessed

assistance and explored the reasons why not, as well as the assistance they are

seeking.

Veterans who are accessing services

and receiving help

4.28

Some individuals appeared to be accessing assistance. While

acknowledging it had taken some time to access, Mr Mark Armstrong

described the services he is receiving:

I have access to a neurologist and a neuropsychologist, a

psychiatrist and a psychologist because of my PTSD tag, so I'm able to get

certain treatments through that. Other things like my brain injury—my eighth

cranial nerve is 31 per cent more damaged on my right-hand side than on my

left-hand side. As I was walking, I'd fall to my right, so I went and got that

tested. That was through the PTSD as well. I suppose I'm one of the lucky

ones—because I have a TPI [Totally and Permanently Incapacitated] gold card I

have access to a lot of different medical things that other people don't.[30]

4.29

Another submitter explained their experience as follows:

My health conditions are accepted by DVA and I consider I

have been well looked after with treatment, hospitalisation and incapacity

payments. My military super was converted to an invalidity pension at

discharge. None of my accepted conditions contain reference to Mefloquine

although my medical documents do so.[31]

Families/partners

4.30

A small number of partners and family members also advised that they

have accessed some support services through DVA, including counselling services

from Open Arms.[32]

While some indicated that support had been of some assistance, others reported

that the experience had not been helpful.[33]

4.31

However, Mrs Susan Armstrong spoke positively about her participation in

the Female Veterans and Families Forum. While she noted there is limited

opportunity to discuss personal circumstances in detail due to the number of

issues in these forums, it did provide an opportunity 'to get to [speak to] someone

in a meeting break'.[34]

Veterans who are getting assistance

but believe it is not working

4.32

Some veterans explained that while they are receiving help, their

current treatment and support has not been very successful in improving their

health.[35]

4.33

Mr Stuart McCarthy explained that although some of his claims to DVA for

issues such as depression and anxiety have been accepted, the available

treatment predominately consisted of medication which has not been of great benefit.[36]

4.34

Mr Aaron King advised that he was classified as Totally and Permanently

Incapacitated (TPI) some years ago and been diagnosed with PTSD but that the

treatment he has received to date has not been effective:

I'm TPI. I was made TPI years ago, not as a part of this [use

of antimalarials]. We only just found out about this a couple of years ago,

about the symptoms. It was put down to PTSD for me. I've got lots of side

effects and problems. It's always just been put down to PTSD. Treatment-wise,

there's Ward 17 at Heidelberg. Now they don't really want me to go, because

they've exhausted all avenues. There's no treatment. I've had [Electroconvulsive

Therapy and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation] ECT, TMS [Transcranial Magnetic

Stimulation] and pretty much every medication. I've been in and out of psych

wards. I've been thrown in jail because they felt there was no other safe place

for me at times.[37]

4.35

Mrs Naomi Kruizinga explained that the medications given to her husband,

Mr Michael Kruizinga, have not helped:

Many times before, Michael has been given a bandaid, or a

temporary fix, to stop his suicidal ideation—more mood stabilisers under the

PTSD umbrella—with most of his network of psychologists and psychiatrists

linking it to just severe depression. Yet he suffers from the neurotoxic

properties of these drugs that were given. None of the medications have worked

since he commenced them over a year ago. If anything, they have made him worse.[38]

Veterans who are not receiving or

seeking assistance

4.36

Worryingly, some veterans told the committee that they are not accessing

help from DVA. In some cases, this was due to a lack of trust in the process.

In other cases, it was suggested that veterans do not have a diagnosis and/or

have not been able to access treatment and support because the effects of

antimalarial medications are not recognised under a single SOP. This is further

discussed later in the chapter.

4.37

Ms Anne-Maree Baker explained:

I have not used the phone lines and made claims for

compensation with DVA because I am undiagnosed. None of my illnesses are

attributed or connected to this trial because nothing has been reported

correctly.[39]

4.38

Mr Stuart McCarthy told the committee

that he has submitted claims for cognitive impairment which have not been

accepted. Further to this, Mr McCarthy stated:

...What's not happening—we are being

refused the support (a) that we need and (b) that we have actually asked for.

And that's exactly the situation that I'm in.[40]

4.39

Other veterans also discussed this issue. Mr Wayne Karakyriacos reported

that '[a] lot of veterans have gone bush and a lot of them are hiding'.[41]

Mr Desmond Rose told the committee that 'most of us don't contact DVA about

tafenoquine anyway...'.[42]

4.40

One veteran, Mr Brian Carlon, is receiving assistance but reported that

dealing with DVA is difficult:

Everything I've done with DVA is a fight, and that fight

takes its toll. I have nothing to do with DVA except: when they send me a

letter, I will send it back. I don't ring them. I don't contact them. It's too

hard on me, because it is a fight.[43]

Barriers to accessing assistance

4.41

As the committee was told that assistance is available and some

witnesses described their experiences of positive support, the committee

explored the reasons why some veterans are not accessing support. These

include: ADF cultural issues, lack of information and difficulties navigating

the claims process.

Cultural issues

4.42

As briefly noted in Chapter 3, some veterans suggested that the nature

of the ADF environment means it is difficult to report health concerns or to

question authority for fear of showing weakness and the potential impact on

career progression.

4.43

On a similar theme, some veterans reported that it is difficult to ask

for assistance. Colonel Ray Martin (Rtd) explained as follows:

Certainly in my experience, and you've heard it today, men

and women in the ADF are self-reliant and very well trained. They're kind of

tough on the outside. As soon as they admit there's a mental health issue, even

though the system says 'come seek help', the reality is you think that if you

put up your hand there's a career detriment to that.[44]

4.44

Mr Rose told the committee that he has only recently started to seek support

for PTSD due to the challenges of seeking help:

It's something you don't like to admit. It's a bit hard,

being a man and saying you've got mental problems. It's not the best.[45]

4.45

Mr Kruizinga acknowledged these cultural issues and suggested that there

needs to be more assistance when a soldier transitions to civilian life.[46]

Lack of information

4.46

Mr Colin Brock reported that information about the trials has not been

shared between Defence and DVA:

I guarantee DVA doesn't know that we were on mefloquine or tafenoquine.

How does DVA know? Defence hasn't told them. We haven't told them.[47]

Mefloquine support line

4.47

As outlined earlier in the chapter, DVA established a dedicated

mefloquine support line to assist veterans who were concerned about

antimalarials. Veterans and their families told the committee about their

difficulties getting advice from this dedicated team.[48]

4.48

Mr Mark Armstrong explained his experience seeking information via the

DVA dedicated mefloquine line:

They [DVA] told me that they didn't have a list of mefloquine

users and to contact the Department of Defence. They did give me a number for

that, and the Department of Defence told me to contact DVA. So I contacted DVA,

and we went back and forth a few times. There was supposed to be some special team

that looked after it. Then, after a while, a lady rang me back, and she was in

a special team—I think they call it a special team or something along those

lines—who don't just look after mefloquine; they look after anything special.[49]

4.49

In a supplementary submission from the Australian Quinoline Veterans and

Families Association (AQVFA), Mr McCarthy described his experience contacting

the dedicated mefloquine support team in DVA. Mr McCarthy details two phone

calls he made to the dedicated number in August and September 2018 seeking

information about the ADF use of tafenoquine. On both occasions, officers were

unable to provide responses to questions. He reported:

The 'dedicated mefloquine support team' was announced by DVA

in 2016. The DVA Secretary has stated that this dedicated team and toll free

number are part of her focus 'on the treatment for veterans who need

assistance', however the staff of the 'dedicated mefloquine support team' do

not hold contact information for healthcare providers and are unaware of the

most basic, factual information regarding the ADF's use of mefloquine and

tafenoquine.[50]

4.50

Following feedback from veterans, the committee was told that DVA made

additional changes to the support line in October this year. The mefloquine

support line is now answered by a team in Canberra that comprises:

...some higher-level staff that actually understand the

detailed nature of our SOPs and who can help any veteran that phones that

dedicated line to assist with their claims—particularly to assist them to

access treatment. [51]

DVA claims process

4.51

The committee heard about the difficulties experienced by some submitters

trying to navigate the DVA claims process, and that some veterans and their

families found it daunting or demoralising.[52]

Some witnesses explained that they were assisted to submit their claims by an

advocate but even with such assistance, veterans provided examples of the

claims process taking up to 10 years.[53]

4.52

The committee heard that support is available to assist to navigate the

claims process. For example, Ms Cosson, Secretary of DVA, told the committee:

We're happy to sit down with a veteran and help them put

forward what they are claiming. Certainly in the...consultation—that we had in

Adelaide and we propose having around the country, where a veteran does

present, which happened in Adelaide, we're able to sit down with them and help

them through the claiming process.[54]

4.53

Professor Nick Saunders AO, Chairperson of the Repatriation Medical

Authority (RMA), emphasised the importance of using an advocate to help

navigate the system:

...there are a lot of veterans who actually could establish a

causal link between their service and their health today if they actually went

through it in a systematic way with their advocate and looked at a range of

statements and principles and a range of conditions that they might have. For

example, we have a statement of principle for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Indeed, the people who are advocating for chronic brain injury being caused by

mefloquine say that there is significant overlap in the symptoms and there's

confusion in the system. Well, if one does have post-traumatic stress disorder,

it almost certainly will be able to be related to the service, and it will be

able then to related to access to appropriate treatment and

compensation—although...access to treatment is less of an issue now [that the

non-liability pathway has been established].[55]

Liability and non-liability pathways

4.54

As previously noted, veterans may access DVA-funded services through two

pathways. DVA stressed to the committee that there is help available to

veterans in need under the non-liability pathway which does not need to be

connected to service-related activities:

In relation to any treatment for anything that's part of the [Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition] DSM-5, which is

anything to do with a mental health condition, which includes brain injury, our

veterans are eligible for free treatment. There are two pathways to get

treatment with the Department of Veterans' Affairs. The first is through that

non-liability line, where you don't need to prove your condition is related to

service, and we will get you straight into treatment.[56]

4.55

Mr Kruizinga was positive about the establishment of the non-liability

pathway:

In recent times, DVA have added a new strain of help that

they call 'non-liability health care'. I believe this is a great step

forward—it means that any soldier can then go and find help for their mental

health—but I think that's a DVA umbrella trying to hide the issue that we are

talking about today.[57]

4.56

Mrs Kruizinga described how this change made a difference to the

circumstances of her husband and family:

When he was admitted into psychiatric in February for a

month, he was only on the white card at that stage. I had to fight tooth and

nail to keep him there, and they were wanting us to pay the cost, which was

quite exorbitant. I was going to have to pull him out, because there is no way

we could afford that. I think a week into his stay, this non-liability kicked

in, which was great...otherwise I would have had to pull him out.[58]

4.57

Alternatively, veterans can submit claims through the liability pathway.

DVA assesses these claims to establish whether the condition was related to the

claimant's service. Claims are also assessed against Statements of Principles

(SOPs). These inform decisions regarding claims for compensation or liability

for service injuries, diseases and death under the legislation relevant to DVA.[59]

SOPs are set out by the RMA, which noted that SOPs 'state the factors which 'must'

or 'must as a minimum exist if service is to be accepted as contributing to a

particular kind of disease, injury or death'.[60]

Professor Saunders emphasised that:

If an exposure can be causally related to a disease or injury

then it can become a factor within a statement of principles, but we do not

make statements of principles relating to exposures to drugs, toxins or those

sorts of things.[61]

4.58

DVA explained that when a veteran makes a liability claim in relation to

the use of antimalarials, it is necessary for DVA to establish that:

-

the claimant had a diagnosable condition answering the claim;

-

the claimant had taken a relevant antimalarial medication;

-

the relevant SOPs (if one has been determined by the RMA)

includes a causal factor relating to the use of that medication;

-

any other requirements set out in the SOP factor are met; and

-

the use of the antimalarial medication was related to the

person's service.[62]

Statements of Principles with

factors relating to mefloquine or tafenoquine

4.59

DVA advised that the RMA has included mefloquine and tafenoquine, either

by name or in more general terms, as a potential causal factor in the SOPs for

a total of sixteen conditions: 16 for mefloquine and six for tafenoquine.[63]

The RMA told the committee that they:

...are confident that we have included mefloquine or

tafenoquine in statements of principle for all diseases or injuries which could

be linked to taking these drugs based upon sound medical scientific evidence

that meets standard epidemiological criteria when examining things for

causation.[64]

4.60

The RMA noted that 'the wording of the mefloquine- or

tafenoquine-related factors in these SOPs requires a close temporal link

between the taking of the drug and the onset of the condition...reflecting the

well-accepted evidence that these agents can have acute neuropsychiatric

effects'.[65]

Ms Cosson suggested that if a trial participant reported an adverse event

during the trial, DVA may be able to use Defence's records to assist with

establishing this temporal link required by the SOPs.[66]

4.61

As noted in Chapter 2, Professor Saunders emphasised that the RMA takes

a very generous view of evidence when they write the SOPs.[67]

Therefore in his view the key for many veterans is getting assistance from an

advocate for example to establish a causal link between their service and their

current health conditions as:

...when the department has conducted reviews in the past about

claims that have been turned down or groups of claims being turned down for a

particular injury, when one looks through the list, there are many other

factors whereby those people could have legitimately claimed and got access to

compensation through the standard route. So there is access to the system. The

statements of principles cover 94 per cent of the claims that are made in the

department, and there is a higher rate of success for claims based on a

statement of principle than for those six or so per cent of claims that are

made, really, not based on statements of principle but relying upon medical

opinion, and the like. So the system is there for people to be able to gain

access to the outcomes of the system and assessment.[68]

4.62

Acknowledging the chronic and complex symptoms being presented to the

committee, Professor Saunders also raised the SOP concerning 'chronic

multisymptom illness' determined in 2014:

We have a statement of principle on an illness called chronic

multisymptom illness. This arose out of an inquiry that we conducted in

relation to Gulf War syndrome. Although this did not satisfy the Gulf War

advocate group that was presenting to us, it became quite clear to us that

there were a significant number of veterans who had quite debilitating symptoms

that fitted into particular patterns of illness, but this wasn't related just

to serving in the Gulf War. In fact, it was related more broadly to deployment

into hazardous environments. So we wrote a statement of principle called

'Chronic multisymptom illness'. That statement of principle is available today

for those people who were deployed to, say, East Timor, took antimalarial drugs

and now have debilitating symptoms that are broad-ranging.[69]

Antimalarial-related claims

4.63

DVA 'has maintained a record of specific claims relating to antimalarial

medications since September 2016'.[70]

As of 30 July 2018, 42 veterans had lodged 53 claims since reporting commenced.[71]

As at 15 October 2018, DVA had received claims from 44 veterans from a total of

71 conditions 'that have been contended as relating the use of antimalarial medications'.[72]

DVA detailed the outcome of the 71 conditions considered:

-

29 have been accepted either consistent with the original claim

or as relating to a different SOP;

-

24 have been rejected as either not meeting the requirement of

the SOP or there being no diagnosed condition as claimed;

-

six have been withdrawn by the veteran; and

-

12 are in progress.[73]

4.64

The veterans who made these claims were deployed to a range of locations

as follows: East Timor (30 veterans), South East Asia (four veterans),

Australia-Pacific region (five veterans), Middle East (two veterans), Africa

(one veteran) and two veterans from an unspecified location.[74]

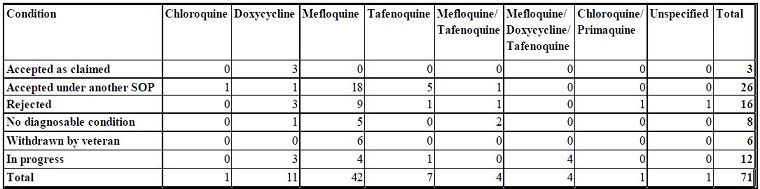

The following table shows which antimalarial medications were being attributed

by the veteran as the cause of the condition being claimed, and the outcome of

the claim.[75]

Table 2: Outcome of claimed condition by antimalarial

medication

Source: DVA, Response to

questions on notice from 11 October 2018 public hearing (received 1 November

2018), [p. 6].

Further investigation of claims by

DVA

4.65

At the hearing on 11 October 2018, Ms Cosson noted that DVA are 'looking

at each individual client claim to understand what the claim was that they were

seeking and to try and understand a little bit further about why they were not

accepted'.[76]

Claims team

4.66

On notice, DVA provided information about the composition of the claims

team:

The dedicated Complex Case Team in the Melbourne office

consists of seven delegates (three APS6 and four APS5) supported by an EL1

Assistant Director, a contracted medical advisor and two social workers. The

team previously consisted of four delegates and was increased to seven

delegates when combined with the Mefloquine Claims Team. The delegates in the

team are experienced and have expertise across the Veterans' Entitlements

Act 1986, the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation (Defence-related

Claims) Act 1988 and the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Act

2004. Mefloquine or other anti-malarial drugs claims receive a higher level

of priority and all calls relating to these claims are handled by the Complex

Case Team.[77]

4.67

DVA further advised that of the seven delegates processing claims, five

have been in the team for greater than 12 months. The team also processes

claims relating to physical and sexual abuse in the ADF and 'given the nature

of these claims delegates are rotated after about 12 months'.[78]

What assistance and support are veterans seeking?

4.68

Given the range of challenges highlighted by veterans and their

families, the committee explored what other assistance and support is being

sought in relation to their health. A range of suggestions were put forward

throughout the inquiry including: acceptance that use of mefloquine and

tafenoquine are the primary cause of the veterans' health issues, improved response

times by Defence and DVA, information and support for families, a proactive

outreach program and tailored treatment programs.

Acceptance of antimalarials as the

cause of health issues

4.69

A number of witnesses called for the use of mefloquine and tafenoquine

to be recognised as the sole or primary cause of the veterans' ill health. Mr Kruizinga

distinguished this from the current situation:

...although DVA have added mefloquine and tafenoquine as the

basis for several SOPs, as a contributing factor, I do not believe yet that DVA

have acknowledged that mefloquine can be a sole factor.[79]

4.70

The AQFVA submission similarly advocated:

That an SOP be established for chemically acquired brain [injury],

quinolone poisoning or similar, to facilitate claims and compensation for

veterans and their families exposed to these drugs during ADF clinical trials

or general military service.[80]

4.71

Lieutenant General John Caligari AO DSC (Rtd), a commanding officer

during the tafenoquine prevention trial, also stated:

In my view, there is sufficient evidence to acknowledge that

mefloquine and tafenoquine are the cause of significant suffering among them. I

believe much more can be done, and needs to be done, to help them...I would like

to see four outcomes from this inquiry: acknowledgement that it is possible

that mefloquine and tafenoquine have an adverse effect on the mental health of

some service personnel and that the treatment may be different to the common

treatments for PTSD; commencement of suitable research to understand how best

to treat those who have experienced adverse effects from the use of mefloquine

and tafenoquine; initiation of a program to identify every service person who

has been prescribed mefloquine and/or tafenoquine and has been adversely

affected by those drugs; and alerting the treating GPs and mental health

practitioners of these individuals that these people need to be dealt with

under a common protocol as directed by DVA and not automatically treated with

PTSD.[81]

4.72

Dr Remington Nevin told the committee:

[A] veteran can derive a significant amount of relief simply from

learning that it's not all in their head; that they're actually sick from a

disease with a name that doctors recognise. I don't think the amount of relief

that comes from simply having their lifelong concerns finally validated can be

understated. Many veterans have suffered with this problem for 25 years. To be

finally told that what they suspected all along is true, that their government

unintentionally or unwittingly poisoned them, can itself be deeply therapeutic.[82]

4.73

Associate Professor Jane Quinn provided her view

...until that acknowledgement is there, it doesn't really

matter what we put in place—that system is still going to ignore that it

exists, and that's always going to be a problem.[83]

4.74

Some of the family members of veterans participating in the inquiry also

highlighted their desire to see the antimalarials publicly recognised as the

primary or sole cause of the ill health experienced by veterans. Mrs Susan

Armstrong, the wife of veteran Mr Mark Armstrong, explained to the committee

that while they were not interested in assigning blame or looking for financial

compensation, they hoped the inquiry could provide:

...acknowledgement and acceptance of the existence of the

permanent adverse health effects of mefloquine; education of medical doctors

and specialists so they understand the permanent adverse health effects that

can arise; funding for long-term studies and research into methods or tests for

detection of toxicity and how to treat to mitigate the adverse health effects;

real and practical support for the veterans and their families; and legislation

prohibiting the testing of drugs on ADF personnel.[84]

4.75

At the public hearing in Melbourne, Mrs Raelene King cautioned:

I find that if this isn't acknowledged—that tafenoquine and

mefloquine have caused this problem—this is not going to move forward. It needs

to be acknowledged that this is the cause of our problem. Without

acknowledgement, it's not going to move forward.[85]

Improving response times

4.76

The committee also heard the view that Defence and DVA should respond

more quickly when contacted by concerned veterans. Mr Benjamin Whiley explained

that he waited two months to receive information from ADFMIDI about the

medication he had taken and then several months to get an appointment with a

doctor and then another four months for the recommended brain injury

rehabilitation program to be approved and commence. Mr Whiley was concerned

about the impact this sort of timeframe can have on veterans' health.[86]

4.77

The need for a timely response to assist veterans was noted by Mr Kel

Ryan, National President, Defence Force Welfare Association:

I have quite a deal to do with DVA in another capacity, and I

would agree that DVA is becoming a lot more responsive than it was 10 or 15

years ago. But the fact that we're only now addressing this very issue, 15 or

30 years after the event, means, to me, we have to become a lot more agile with

the way we deal with these issues. I know enough about soldiers and soldiering

to say that people present with issues, often, many years after they've left

the service, and they present because of triggers that might not have occurred

20 or 30 years ago that have suddenly occurred. So somehow or other we need to

get a more agile process to deal with these issues.[87]

4.78

As noted above, some claims, even with the assistance of an advocate,

have taken up to 10 years to be finalised. Some individuals the committee spoke

to were clearly in need of more immediate assistance.

Information and support for

families

4.79

As has been raised in other inquiries undertaken by this committee,

support from the partners and family members of veterans is very important.

Several veterans who provided evidence to this inquiry did so alongside

partners, parents and other support people. Similar to the experiences of the

veterans themselves, family members reported difficulties accessing information

about the ADF trials, veterans' health records and any support that may be

available.

4.80

Mrs Naomi Kruizinga, wife of a veteran, outlined some challenges her family

experienced when in crisis.

I was completely overwhelmed. I had three children trying to

make sense of what had happened and unable to give their dad a hug at night. I

had to keep going, and I was the only bread winner. There was no assistance

from DVA. They couldn't do anything. Except offer a one-time payment of 900

[dollars] to tide us through. We have had to get food vouchers from RSL and

bravery trust to get us [by]. Hock personal belongings to help us through. Why

is there no help from your government for this? I am not the only family who is

going through this right now.[88]

4.81

In addition to providing counselling services, Mrs Kruizinga asked that

more coordinated support be available for families:

Especially for the children as well—they do give us

counselling, but there needs to be sort of a team involved that will come out

and help assess each family individually and try and find out what supports

they need, whether it's financial assistance, other things as well. There's

no-one out there like that. We have to make the calls. When you're so busy

dealing with him in hospital—I don't have the time and I have three children

whose needs I have to look after as well. Having that team come in and help me

would be highly beneficial, just to take that load off.[89]

4.82

The role of ex-service organisations was also discussed. Mr and Mrs

Kruizinga explained that their children had attended 'highly beneficial'

support programs with Legacy and also accessed some services from the RSL. Mrs

Kruzininga explained that because there is no coordination between ex-service

organisations, as well as with DVA, family members must approach each service

individually to find out what assistance is available.[90]

4.83

When describing her experience, Mrs Raelene King also advocated for more

support for children to be available:

I would also perhaps like to see a quinoline support group for

all children of affected trial participants to establish what the impact these

psychological effects have had on them. My children are adolescents and adults

now. Personally, seeing my husband go through this has affected me deeply in so

many ways. So try to imagine seeing this through the eyes of my children.[91]

Proactive outreach program

4.84

Several submissions and witnesses advocated for a proactive outreach program

to be initiated whereby all trial participants are contacted individually to

inquire about their health and to check whether support or assistance is

required.[92]

For example, Mr Benjamin Fleming, a veteran who participated in the

mefloquine prevention trial, was supportive of a broad outreach program

because:

...there are a lot of people out there who don't know they have

got the issue....Defence and DVA, et cetera, have in their means the ability to

contact every individual who has consumed these drugs. The first step is very

much to reach out to them and help educate.[93]

4.85

He called for a program 'funded to speak with every Defence Force member

who consumed these drugs—not just one that focuses on sufferers in Townsville'.[94]

Also appearing at the public hearing in Brisbane, Mr Whiley agreed that an

'outreach program is vital' and that such a program 'needs to occur at a faster

priority'.[95]

4.86

The AQFVA called for the establishment of a working group:

...encompassing veterans advocates experienced in the effects

of quinoline toxicity with appropriate, independent advisers sourced from the

military mental health community, family services, occupational health

practitioners, brain injury rehabilitation specialists, neurologists,

psychologists, cognitive and behavioural experts and psychiatrists, to

establish a recommended assessment and treatment program for those affected by

mefloquine and tafenoquine during their military service.[96]

4.87

It further suggested that such a group 'be appropriately resourced to

deliver a national outreach and rehabilitation program for quinoline veterans

and families in Australia'.[97]

The AQVFA submitted a proposal to then Minister for Veterans' Affairs, the Hon

Dan Tehan and DVA in December 2016 to direct a pilot outreach, rehabilitation

and research program for quinolone veterans and families.[98]

The AQVFA's outreach program proposal was supported by other participants in

the inquiry.[99]

Mrs Kruizinga emphasised that a broad ranging outreach program would also be

able to provide assistance for families and advise about other support

services:

This is where having this outreach program that can do the

advocacy and the support and all that for the families is really beneficial,

because it's just too overwhelming. I'm just so focused on the children and my

husband that I just don't get the time to do that.[100]

4.88

Associate Professor Quinn told the committee that when responding to the

proposal from the AQVFA, Minister Tehan did not support the proposal and noted

that there are existing services available through DVA, or through Defence for

serving members.[101]

4.89

Dr Remington Nevin noted that the American Quinism Foundation has recommended

that all recent American veterans be screened for a history of symptomatic

mefloquine exposure.[102]

Tailored treatment programs

4.90

The committee heard views from veterans that current treatment options

are not sufficient to meet their health needs. Veterans reported that the difficulty

in obtaining a definitive diagnosis covering the complexity of their health

issues also makes it more difficult to access treatment.

4.91

Mr Kruizinga explained that the DVA process is one of exclusion or

elimination to reach a diagnosis, which in his case, after numerous tests, has

not been reached.[103]

4.92

The Defence Force Welfare Association also expressed concern about the

effect of an incorrect diagnosis:

The absence of effective diagnostic routines, referral

protocols and dedicated rehabilitation programs is leading to very poor health

care. Affected individuals are commonly wrongly diagnosed with posttraumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) or other mental health disorders and subsequently

subjected to treatments which fail to improve their condition and may

inadvertently make it worse. The patient's neurological and psychological

difficulties arise not from a functional brain problem as current treatment

follows but from a structural change problem, drug mediated, that will require

a different treatment approach. Here in lies the reason for these individual

patient's failure to thrive. And for their on-going treatment.[104]

4.93

Associate Professor Quinn noted she has received reports from veterans

that address a 'common theme':

That certainly seems to be the common theme that runs through

the experience of the people that I talk to. They have ease of access to

psychiatry and they have ease of access to counselling, but if they ask for

something that sits outside any of those particular domains then all of a

sudden [their] SOP and their claim doesn't fit, and accessing that treatment

becomes almost impossible.[105]

Treatment for neurocognitive issues

4.94

As outlined in Chapter 2, the AQVFA has argued that mefloquine has

caused 'lasting or permanent brain damage, with chronic symptoms typically

misdiagnosed as PTSD or other psychiatric disorders'.[106]

4.95

Dr Nevin indicated that in his view that treatment 'is a little

premature to discuss'.[107]

However, veterans who provided evidence to the inquiry supported the view that

additional treatments needed to be available that address potential brain injury

and other neurocognitive issues.[108]

4.96

Associate Professor Quinn explained that treatments for brain injuries acquired

from taking antimalarials are not currently available:

I think the treatments that are lacking at the moment are

those that are applied to an actual brain injury as opposed to those that are

applied to a psychiatric condition. In the vast majority of cases of people who

have suffered long-term side effects from these drugs, what we see is the

profile of, essentially, a brain injury.[109]

4.97

Furthermore, Associate Professor Quinn explained that in her view, should

someone be incorrectly diagnosed with PTSD, they will be unresponsive to that

treatment:

What we see is that people who are treated for post-traumatic

stress disorder without having that as an absolute formal diagnosis that is 100

per cent correct—when that post-traumatic stress disorder is present as an

accumulation of symptoms caused by that underlying brain disorder, they're

actually non-responsive to the treatments for PTSD, and that's extremely common

in this group.[110]

How can the concerns raised by veterans be addressed?

4.98

While acknowledging the actions already undertaken by Defence and DVA to

date, the challenges and barriers reported by veterans demonstrate that these

actions are not meeting the needs of all veterans. The committee heard a number

of suggestions from veterans about the assistance and support they would like. Noting

the challenges of coming to an agreed position on the cause/s of their symptoms

between the veterans and their advocates and the medical community, the

committee discussed how best to address their health concerns.

Improving connections with the veteran

community

4.99

The committee heard various suggestions for how to improve the

connections between veterans and service providers, to ensure that veterans are

accessing the support to which they are entitled. It appeared that while

submitters agreed on this general point, views varied on how this could be

achieved. While many in the veteran community were calling for a proactive

outreach program, other evidence to the inquiry highlighted concerns with that

approach.

Ethical and practical concerns regarding proactive outreach

4.100

The committee was told that this kind of 'active outreach program' could

cause additional and unnecessary suffering to veterans and 'could also

undermine measures being applied more broadly to address the mental health of

veterans'.[111]

Associate Professor Harin Karunajeewa cautioned that it is:

...hard to see how such a program could be implemented without

implicitly suggesting to recipients of the outreach that their symptoms are

indeed related to previous drug exposure. This approach is therefore highly

susceptible to an important and very well characterised phenomenon known as

'recall bias'. It effectively becomes a 'self-fulfilling prophecy' and one

which I believe would contribute significantly to anxiety and other

psychological morbidity in these veterans.[112]

4.101

Defence has on a number of occasions indicated it does not support

undertaking a proactive outreach program as it is concerned that this approach

could potentially cause veterans undue harm. VADM David Johnston AO, Vice Chief

of the Defence Force explained:

Defence has considered whether individual follow-up of all

those who were involved in the antimalarial studies in the late nineties and

early 2000s is warranted. The vast majority of individuals who have taken these

medications are unlikely to have ongoing health problems. Our view has been

that contacting this majority might cause more harm than good. It may cause

unnecessary worry to individuals who have no reason to be concerned. The

significant profile of this issue now and the confusion that may now exist

amongst study participants mean that we need to keep this approach under

review.[113]

4.102

Defence suggested that there may be benefit in future outreach

activities being:

...focused more broadly on encouraging all veterans with any

health concerns to seek help, rather than specifically focussing on this group.

It remains pivotal that veterans and their families understand the services

available to them regardless of their diagnosis, many of which can be accessed

through DVA or through their GP, who are best placed to investigate, manage and

if necessary refer patients for specialist advice.[114]

New consultation program

4.103

An important issue is enhancing trust with this group of veterans as the

committee heard some have lost trust in the system, such as Ms Anne-Maree

Baker, who told the committee 'I have a real distrust in the government, the

military and any institutions because of my experiences since 2001 when my

health started to decline'.[115]

Mr Stuart McCarthy similarly said 'I have zero trust and zero faith in any

democratic institution in this country, because the culture of those

institutions is denial, at best'.[116]

4.104

As outlined above, DVA will be holding a series of consultation forums.

The consultation forum mechanisms may present an opportunity to enhance trust by

facilitating greater collaboration and fostering connections between veterans,

families, advocates and service providers, particularly DVA.

Improving cooperation

4.105

Ms Cosson, Secretary of DVA, acknowledged that there has been differing

views on what should be regarded as 'outreach' and, as a result, DVA is

undertaking what they are referring to as 'consultation'.[117]

Ms Cosson observed that, among the attendees at the recent Adelaide consultation

forum, there was not a strong level of awareness about what services are

available generally to veterans:

Recently we had a consultation session in Adelaide and we

talked with our veteran community. Forty of our veterans and families

participated in that consultation. What seemed to be a gap in understanding is

that when we introduced non-liability health care in the budget last year we

extended that free treatment for any condition that's listed in the DSM-5.[118]

4.106

Following the 11 October 2018 public hearing, DVA provided more detail

about the Adelaide forum including a summary of areas discussed which included:

health experiences related to ADF service (including experience with

antimalarial medicines), a lack of awareness of what supports are available

through DVA or Defence and concerns about how to access the mental health

workforce eg. psychiatrists and psychologists in Adelaide and South Australia.[119]

4.107

A number of suggestions came out of the public forum held in Adelaide. DVA

advised that attendees were invited to provide feedback via a short survey and

that overall, attendees reported that the 'forum provided helpful information

and a good opportunity to openly discuss their concerns'. However:

...some felt that the discussion became too emotional and that

a smaller group might help facilitate a more focused and comfortable discussion

for attendees. Attendees also identified that additional information on

available supports and services, including non-liability health care

arrangements, would be helpful.[120]

4.108

Regarding the forum in Adelaide, Associate Professor Quinn noted the

need to build on the information provided:

The other thing that did seem to be a deficit in the way the

first one [session in Adelaide] was carried out was that there really wasn't

any provision of information about what the next step for those people needed

to be other than 'put in your claims'. So we always give effect to this

circular—whatever you want to do, put in your claims.[121]

4.109

Associate Professor Quinn also suggested that DVA could proactively

contact groups such as the AQVFA to inform them of upcoming consultation or

information-sharing activities. She noted that in relation to the DVA sessions

held in Adelaide:

...what was interesting was that we [the AQVFA] weren't

informed of any of them directly. We found about the dates of all of them

through ex-service organisation members who have been on the mailing lists for

them, which is odd because I have Liz Cossin's personal email address and Tracy

Smart's mobile number and either of them could have given me a call and told me

when they were.[122]

Ensuring GPs have access to

relevant information

4.110

One of the key messages from Defence has been for those concerned to

seek assistance from medical practitioners. GPs are therefore central to

ensuring veterans have access to a range of health services and ongoing

support. Dr Penny Burns, representing the Royal Australian College of General

Practitioners (RACGP) explained the organisation's role:

The role of the RACGP in this discussion is around ensuring

general practitioners are available to provide ongoing support to veterans

affected by mental health symptoms and/or physical symptoms, whatever the

cause. Their aim is to continue to update GPs so they can provide the best

evidence based treatment on an ongoing basis. The aim is to decrease the level

of dysfunction experienced with symptoms and get people back to more normal

lives. In practice, when people present with symptoms—mental health issues, for

example—it's sometimes not possible to definitely define a cause, but, in most

cases, we're still able to look at managing symptoms to improve the conditions.[123]

4.111

Furthermore, Dr Burns emphasised:

In summary: the RACGP is keen to ensure easy access by

veterans to GPs for any support needed—be it for mental health symptoms and/or

physical symptoms, or just general distress; whatever the cause—and to ensure

that GPs are educated to provide the best possible evidence based support,

diagnosis and treatment for veterans.[124]

4.112

Evidence to the inquiry has reported varying levels of awareness among

GPs of the mefloquine and tafenoquine antimalarial drugs and it was suggested

that more needs to be done to better educate GPs about the issues being

reported by veterans.[125]

4.113

Officials from DVA recognised the important role of GPs to provide

assistance to veterans as well as the role that DVA has to support and educate

GPs:

...What we are very aware of, as I've looked into this and I've

worked with my colleagues and I've worked across the last year, is that we need

to find ways to educate our GPs better so that, when veterans present with this

type of disorder, there is a very clear, signposted way for people to get to

these specialists—because it is a specialist area.[126]

4.114

Dr Burns said most GPs would have a reasonable understanding of

mefloquine due to the fact that mefloquine 'has been used for quite some time'.

She spoke about the resources that have been made available to increase awareness

about mefloquine:

My understanding of most of the GPs who I know is that they

would have a reasonable understanding of that. There have also been clinical

guidelines brought out by the Joint Health Command. Recently, I think that the

Gallipoli Medical Research Foundation and the Returned Services League of

Australia put out a comprehensive brief on some PTSD stuff. And there has also

been some stuff coming out recently about mefloquine as well. So there's a lot

of education that comes out continually to GPs around that.[127]

4.115

Dr Burns noted that as tafenoquine is new, GPs would not typically have

received information about that yet:

Tafenoquine, no. I hadn't actually heard of it before or seen

it before the invitation to this inquiry. So, if I'm an example of the average

GP, I would presume that they don't have much information around that.[128]

4.116

Mr Karl Herz, Biocelect, informed the committee about the information

they will be providing to GPs leading up to the official release of

tafenoquine. As well as the information that is already provided on the TGA

website, Biolcelect is finalising a 'Dear Doctor' letter which will provide

information about the medication with a focus on explaining the

contraindications.[129]

Ensuring information sharing

between health professionals and DVA

4.117

As noted earlier in the chapter, DVA has undertaken activities to

increase GPs' awareness of the use of antimalarials in the context of the

veterans' community. Dr Burns noted that the clinical guidelines for GPs

produced by DVA and Defence 'are fantastic' and the importance of ongoing

information sharing and promotion across GP groups:

I think that one of the things that need to happen is that it

needs to be promoted through all the GP groups continually, and workshops and

webinars are the ways that GPs are now accessing information. I think having

the GP groups involved—so the AMA [Australian Medical Association], the

college, ACRRM [Australia College of Rural and Remote Medicine], the various

groups, promoting it. I think webinars, workshops, guidelines particularly—GPs

love guidelines and workshops. At the moment, there's a big conference, the

annual GP conference, GP18. That's another way of getting information out to

GPs.[130]

4.118

Dr Burns suggested that the provision and promotion of this sort of

information was particularly relevant around major bases as well as in other

locations where there is high volume of 'travel back and forth between malarial

areas'.[131]

4.119

On notice, the RACGP explained that a RACGP representative attends the

DVA Health Providers Partnership Forum[132]

meetings three or four times a year to provide advice to DVA about developing

information resources for veterans. Attendance at these meetings also

facilitates information sharing back to the RACGP about DVA programs.

Furthermore, the RACGP 'helps to distribute DVA information and resources

through RACGP publications' and has endorsed a number of resources that provide

information and support for veterans.[133]

Additional research underway

4.120

Professor Sandy McFarlane AO, Director of the Centre for Traumatic

Stress Studies, stressed the need for research which is independent in order to

provide reassurance to veterans about the findings.[134]

The committee is aware that Defence and DVA have jointly commissioned the

University of Queensland to undertake a research study on 'Self-reported health

of ADF personnel after use of antimalarial drugs on deployment'[135]

using 'de-identified data extracts from the Bougainville, Timor-Leste, and

Solomon Islands deployment health studies'.[136]

4.121

In its submission, DVA explained the new research will:

...focus specifically on the health outcomes of deployed

veterans who took anti-malarial medications. It is anticipated that this

research will be completed in the second half of 2018.[137]

4.122

Defence added that this research will examine the following research

questions:

- Did deployed veterans who reported taking mefloquine have

different rates of mental and general health outcomes compared to veterans who

reported taking doxycycline or other antimalarials?

- Did deployed veterans who reported taking primaquine on

return to Australia have different rates of mental and general health outcomes

compared to veterans who did not?

- Did deployed veterans report a significant reaction to

specific medications received during their deployment or raise use of

antimalarial drugs as an area of concern in response to open ended questions?[138]

4.123

At the time of the hearing in October 2018, there was no further

information available about the ongoing research. It was confirmed that the

research will be finalised later in 2018 and that the report will be published.[139]

The need for a multi-disciplinary

approach

4.124

The health issues identified by veterans in this inquiry are complex

with several individuals submitting long lists of symptoms and documenting a

range of conditions. Some had been diagnosed with particular conditions by a

health professional while others were still undergoing various tests and

consults to determine a diagnosis.

4.125

It was noted that responding to such varied and complex health needs

requires a multi-disciplinary approach. One veteran described the range of

supports he needs as follows:

One of my recommendations moving forward is that sitting in

front of a psychiatrist and being prescribed medication is not going to help or

do anything for my brain injury. What I need is psychosocial support...I've got

to the point where I need to start re-learning how to do things. I've managed

to get access to a social worker and I'm basically learning how to schedule a

day and tasks—things like that—and that's the support that we need.[140]

4.126

The RACGP has defined 'multidisciplinary care' as occurring:

...when professionals from a range of disciplines with

different but complementary skills, knowledge and experience work together to

deliver comprehensive healthcare aimed at providing the best possible outcome

for the physical and psychosocial needs of a patient and their carers'.[141]

4.127

Health professionals may include community health professionals, general

practitioners, and medical specialists. This approach is often used to treat

and support people with conditions such as cancer, and systematic approaches to

team based care are also emerging in 'primary care clinical areas such as

diabetes, aged care, mental health and disability'.[142]

4.128

Associate Professor Quinn emphasised the importance of including a broad

support network when providing treatment:

Managing those [people with brain injuries] isn't just a

matter of giving somebody a script with an antipsychotic or a sedative drug and

expecting them to go away and get better. There is also a whole family support

network that needs to be drawn up around somebody with a long-term brain

injury. If we were looking at somebody who had been brain injured in a car

accident and was going to be anticipated to have long-term neurological and

cognitive deficits, there's no way that we would be suggesting that that person

was going to manage their environment, manage their work-life balance or manage

their employment prospects without having a network of support around them and

their family. This is the thing that is missing when we have a situation with a

system that doesn't recognise this as a brain injury.[143]

4.129

Dr Stephanie Hodson CSC, National Manager, VVCS, DVA, acknowledged that

it can be challenging to confirm a diagnosis when individuals present with a

range of complex symptoms. The symptoms reported by veterans are wide ranging:

concerns about the 'neurocognitive element', anxiety, PTSD as well as other

'somatic symptoms' including digestive issues and skins problems. She

acknowledged that the complexity of these issues requires a holistic response:

All of this means that we've got to get to person-centred

care. We've got to have a way that we assess comprehensively the individual for

all those domains and then assist them to get to pathways. Just saying, 'Go to

your local GP,' doesn't necessarily mean that you're going to get the sort of

wraparound assessment you need. We need to help GPs actually identify the more

complex individuals who we need to put into a signposted pathway where we can

link them to the right professionals.[144]

4.130

Dr Hodson spoke further about the recognition by DVA that some

individuals need tailored, wrap around assistance which needs to include

neurocognitive aspects:

Across this journey, we've reached back into the department.

We hadn't, when we first started, thought a lot about rehab. With the pathways

to care that [Mr Stuart McCarthy] talked about, we are now figuring out how

someone gets there from maybe turning up in a VVCS office. We do the right

assessment and say, 'We do think there are some problems here that are not down

the anxiety end of the spectrum, or PTSD; they're actually in the

neurocognitive end,' and we now need to get those people to rehab specialists,

to speech pathology, and we are working for the first time ever with rehab

occupational therapists. There's a whole specialty here.[145]

Neurocognitive Health Program

4.131

In addition to offering existing treatments and support through DVA's

non-liability pathway, DVA advised that they are developing a new Neurocognitive

Health Program to assist veterans who may indicate symptoms of a neurocognitive

disorder (NCD). This program has been developed following feedback from

veterans that they have been unable to access appropriate support to address some

of the concerns they have attributed to mefloquine use.

4.132

Dr Hodson advised that:

The DSM-5 [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders] made quite a big step forward around the fact that we all do tend to

forget the brain and psychology. Mental health is all interconnected, and it

starts with the brain. There is an area in the whole diagnostic continuum which

is about neurocognitive disorders, which can be caused from a range of issues.

It can be exposures, it can be playing sport, it can be mild traumatic brain

injury and it can be long-term life alcohol use. All of these can result in

impacts that are about a loss in memory, speech, neurocognitive functioning.[146]

4.133

Dr Hodson explained that a number of veterans from the 'mefloquine

cohort' had raised concerns that when they have tried to access DVA services to

discuss a possible brain injury, the response was to discuss PTSD.[147]

This experience reported by Dr Hodson is consistent with the evidence to the

committee's inquiry.

4.134

Dr Hodson explained that DVA had reflected on those representations and

acknowledged that the response to veterans' concerns may need to change:

We acknowledged, about a year ago, that we were not well

equipped to be able to do those assessments. It's actually a very specialised

area within the community. Over the last 12 months, we've been working really

hard to look at whether this is an area we can measure. The good news is that

we've we talked to Westmead Hospital and we've talked to people like Professor

Richard Bryant and Dr Ian Baguley, who do specialist work in this area, and

they've said that the science has really moved forward. A lot of it has come out

of the US to do with mild traumatic brain injuries. In fact, we've now got much

better neurocognitive screening that we can do. Importantly, there is

remediation we can do to bring about better outcomes.

What we're trying to do at the moment is develop a pathway so

that, if you come in, we can baseline where your functioning is. For anyone who

has served in the military, that's super important. If you've had a 20-year

career, you may have been around exploding ordnance, you may have played a lot

of rugby, you have potentially had toxic exposures, you may have drunk a bit of

alcohol—there are a whole range of reasons why your cognitive functioning would

be putting you at risk for early onset Alzheimer's down the track. We want to

be able to assess functioning baseline for anyone who is worried about

functioning. Where we find there is a problem, we have to have pathways to

care.[148]

4.135

It is envisaged that the program will be accessible to veterans assessed

as requiring treatment from anywhere in Australia. The assessment of current

functioning and provision of treatment will not be linked to any possible

cause.[149]

4.136

Dr Hodson further reported to the committee advice she has received from

a neuroscientist:

...it doesn't really matter whether the inflammation in the

brain was caused by PTSD or it came from a toxic exposure; at the end of the

day we've got to work with the inflammation of the brain.'[150]

4.137

This program is being developed 'initially through a Discovery Phase of

consultation and co-design to establish what the service would need to

provide'.[151]

In his submission, Professor McFarlane, noted that he has been asked by DVA to

advise on the development of the Neurocognitive Health Program. Mr Stuart

McCarthy also advised the committee that the AQVFA was invited to 'co-design

this program with them, in consultation with ABI rehabilitation specialists

already experienced in providing health care to affected veterans...'.[152]

4.138

Associate Professor Quinn also discussed the development of the Neurocognitive

Heath Program and in particular focused on the benefits of the co-design model

being used for its development as an example of different groups working

together in a cooperative manner:

I think we're beginning to work on that with the