Chapter 3

Identification and disclosure of mental ill-health

Introduction

3.1

This chapter considers the mental health strategies for ADF members and

veterans; identification and disclosure policies in the ADF in relation to

mental ill-health; and recordkeeping for mental ill-health for ADF members.

ADF Mental Health Strategies

3.2

In 2002 the Department of Defence (Defence) developed its first Mental

Health Strategy (MHS), seeking to promote mental health and wellbeing as well

as raise awareness of suicide and the misuse of alcohol, tobacco, and other

drugs. In 2009, the Review of Mental Health Care in the ADF and Transition

through Discharge (commonly referred to as the Dunt Review)

was published. The Dunt Review praised the ADF finding that its MHS compared

favourably to mental health strategies from militaries in other countries:

The establishment of the MHS by the ADF in 2002 was

far-sighted. The Strategy compares favourably with mental health strategies in

other Australian workplaces. It also compares favourably with what exists in

military forces in other countries. Some of these military forces have mental

health policies and programs in place, particularly in relation to PTSD. Others

have individual mental health programs in place however they do not have the

suite of programs at a whole of forces level that exists in the ADF. The

enthusiasm and commitment of ADF members in delivering these programs adds to

the ongoing achievement of the MHS. This has meant that programs are well

received by members.[1]

3.3

The Dunt Review noted that, despite its achievements, the ADF's Mental

Health Strategy needed further improvement 'for it to truly be a Strategy,

rather than a small number of small programs as at present'.[2]

The Dunt Review made 52 recommendations.[3]

ADF Mental Health Reform Program

3.4

Defence commenced the Mental Health Reform Program in 2010, based

substantially on the findings and recommendations of the Dunt Review.[4]

Defence invited a number of external mental health experts, clinicians, policy

advisors and researchers (including Professor Dunt) to form the Mental Health

Advisory Group, together with representatives of Joint Health Command (JHC),

single Services, Defence Community Organisation, Defence Families Association,

Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) and the Veterans and Veterans Families

Counselling Service (VVCS). The Group has met seven times.[5]

3.5

In 2011, Defence released its Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy

(MHWS) and in 2012 released the supporting Mental Health and Wellbeing Action

Plan (MHWAP).[6]

The MHWAP lists six strategic objectives and the priority actions that need to

be taken to achieve them (see Table 1.1). The MHWAP also outlines the goals and

deliverables and describes 'what success will look like', for each of the

objectives.[7]

The Chief of the Defence Force (CDF), Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC,

outlined Defence's achievements in the area of mental health since 2009:

...we have upskilled and increased our mental health workforce

as well as strengthened our resilience training and prevention strategies,

which now begin at recruitment. We have improved the screening programs used to

identify problems and we have also undertaken world-class mental health

research and surveillance. As a result, we know more now than at any point in

our history about the impact military service can have on the mental, physical

and social health of current and ex-serving personnel. We have a comprehensive

body of data about the causes and prevalence of mental health issues in the

Australian Defence Force population.[8]

3.6

Defence advised the committee that it has implemented all 52 of the

recommendations from the Dunt Review, investing $146 million in mental health

services and support (as at 30 March 2015). Defence has improved policy and

training for Defence health professionals; increased mental health research and

surveillance; and strengthened resilience training and prevention strategies.[9]

3.7

The Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL) commented on the

MHWAP, stating that its priority actions, whilst positive, are far from

achieved:

These hoped for outcomes have at best been only partially

obtained at this point in time and a great deal more work is yet to be

undertaken in order to achieve them. Too many individuals are suffering in

poorly managed circumstances at the present time without the necessary care and

supervision that's required from a number of appointed agencies.[10]

3.8

Consultations for the development of the ADF Mental Health and

Wellbeing Strategy 2016-2020 commenced in March 2015. The consultations are

being led by Joint Health Command and 'will involve engagement with a broad

range of stakeholders, both internal and external to Defence'.[11]

Table 3.1 – Strategic objectives

and priority actions of the ADF Mental Health and Wellbeing Plan 2012-15

|

Strategic

Objectives

|

Priority Actions

|

|

Promote and support mental fitness within the ADF

|

Addressing stigma and barriers to care

Strengthening the mental health screening continuum

Improving pathways to care

Developing e-mental health approaches

Developing a comprehensive peer support network

|

|

Identification and response to mental health risks of

military service

|

|

Delivery of comprehensive, coordinated, customised mental

health care

|

Improving pathways to care

Enhancing service delivery

Upskilling service providers

|

|

Continuously improve the quality of mental health care

|

|

Building an evidence base about military mental health and

wellbeing

|

|

Strengthening strategic partnerships and strategic

development

|

Strengthening the mental health screening continuum

Enhancing service delivery

|

Department of Defence, ADF

Mental Health & Wellbeing Plan 2012-15, p. 11.

Requirement for ADF members to be 'medically fit'

3.9

Defence has an obligation to ensure that ADF member's duties do not

detrimentally affect their health, that ADF members can undertake their duties

without compromising the safety of themselves or others, and that the ADF as a

whole maintains its operational capability. As outlined in the 2013 Review

of Health Information Practices in Defence, Defence must balance the health

of the individual ADF members with the effect that an individual's health issue

may create within an operational situation:

The requirement that a member be fit for the performance of

their duties is of paramount concern to the ADF. A member's employability and

deployability goes to the very reason for being of the ADF; its operational

capability. Members must be fit to undertake their duties without compromising

the safety of themselves or others. Defence has an obligation to ensure that

the undertaking of their duties does not have detrimental effects on the

member's health. Accordingly the seeking of health treatment by a member, the

provision of health treatment to the member by the Commonwealth, and, the

requirement by the ADF that a member undergo a health examination or treatment,

renders the provision of such a service as being outside the normally

understood relationship of health practitioner and patient. The relationship

becomes a 'three cornered' relationship with the ADF having a clear interest

not only in the effect of a member's current health statement vis-à-vis the

individual but also the greater effect that any health issue may create within

an operational situation.[12]

3.10

The Defence Act 1903 provides for regulations to be made in

relation to medical treatment of ADF members and cadets. It a condition of an

ADF member's service that they be physically and mentally capable of performing

the duties required of them and, if determined to be medically unfit (including

unfitness because of incapacity due to mental ill-health), a member's service

may be terminated under the provisions of the Defence (Personnel)

Regulations 2002.[13]

3.11

ADF members may be ordered to submit to medical examination. Part 6 of

the Australian Military Regulations 1927 provides for compulsory medical

examination of an Army member where directed by a superior officer to so

attend, including the requirement that the member provide the person conducting

the examination with all information and do anything required by the examiner

for the purpose of such an examination.[14]

Part 4 of the Air Force Regulations 1927 also provides that an Air Force

member may be examined in a way approved by the Chief of Air Force to determine

a member's level of medical fitness.[15]

The Navy operates similarly, however without such a legislative provision.[16]

Screening and early identification of mental ill-health

3.12

The Chief of the Defence Force stated that 'we are looking for early

recognition of a mental health injury and then looking to get early

rehabilitation to be able to get people back to work'.[17]

Defence advised the committee that it has implemented a comprehensive Mental

Health Screening Program to identify and provide assistance to individuals who

have been exposed to potentially traumatic events through activities such as

deployments, Border Protection operations, humanitarian and disaster relief

missions or training accidents.[18]

Referral pathways

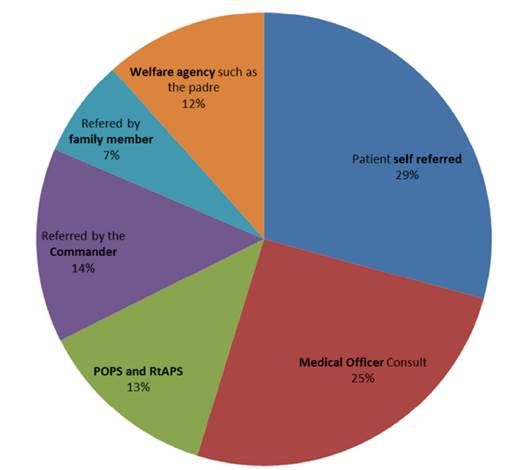

3.13

Aspen Medical found that the most common referral pathway for ADF

members seeing a mental health professional was self-referral (29 per cent),

closely followed by referral by a Medical Officer (25 per cent) (See Figure

3.1). Aspen Medical noted that this suggests that ADF mental health policy

regarding the shared responsibility between commanders, individuals, and

clinicians for the identification and early treatment of mental ill-health is

working:

This success is evident in the high self-referral rate. It is

possible that another person such as a commander, padre, family member or

friend encouraged a patient to self-refer. However, the high rate of

self-referral indicates that many individuals are willing to seek treatment. It

also suggests that the stigmatism, once attached to [ADF members] mental

health, is changing at the individual level.[19]

Figure 3.1 – Referral Pathway for

Mental Health

Aspen Medical, Submission

38, p. 15.

3.14

Some submissions questioned the effectiveness of screening in the early

identification of mental ill-health.[20]

Walking Wounded acknowledged that ADF mental health evaluation screening has

'improved markedly over recent years', but noted that it can be circumvented by

ADF members who do not wish to be identified as struggling with mental

ill-health:

The concept of post-operational psychological screening

(POPS) is good but can often be "gamed" by soldiers who are keen to

go on leave, etc, rather than be delayed by admitting to stress disorders.

While not widespread, there are many who feel that once they go on leave, they

will return to normal. Sadly, we know this isn't always the case.[21]

3.15

However, Dr Kieran Tranter informed the committee of a recent study,

using participants from the MHPWS, which considered the diagnostic accuracy of the

screening tests used by the ADF—the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10),

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and the Post-traumatic

Checklist (PCL)—in a population-based military cohort. [22]

The study found that 'all three scales showed that good to excellent levels of

overall diagnostic validity' and 'could sensitively detect disorder whilst

maintaining good specificity'.[23]

3.16

Aspen Medical noted that it has found that screening activities are

'useful at identifying early some [members] who need help'. Aspen Medical

commented that the number of referrals to medical health professionals from

Post Operational Psychological Screening and Return to Australia Psychological

Screening indicates that screening is effective at early identification of

deployed member's mental ill-health and that 'this suggests that the policy and

conduct of these mandatory screens are achieving the effect that they were

designed to achieve'.[24]

3.17

Currently, there are a number of time points or key events that trigger

mental health screening within the ADF, with approximately 8,000 members being

screened every year. The majority of mental health screening is connected to

deployment and after critical incidents. ADF member's participation in

psychological screening, both on deployment and after returning from deployment,

is mandated by each operation's Operational Health Support Plan (OHSP). Routine

physical health checks, which occur every three to five years, also include an

alcohol use screen.[25]

3.18

Defence advised that mental health support and screening may also be

tailored to meet the requirements of a particular operation, giving the example

of the program for Operation RESOLUTE, which aims to provide psychoeducation,

surveillance and early identification and referral of members who require

follow-up mental health support.[26]

Types of screens

Return to Australia Psychological

Screening (RtAPS)

3.19

Return to Australia Psychological Screening (RtAPS) is provided to all

deployed ADF members nearing the end of their deployment. The aims of the RtAPS

are to document traumatic exposure; document and manage current psychological

status; provide advice and education to facilitate a smooth post-deployment

transition; and provide information to Command on the psychological health of

the deployed force. Further, in addition to identifying individuals at risk and

arranging referral for more detailed assessment, the data gained from the RtAPS

is used by the senior psychologist to brief the deployed element commander and

to enable trend analysis.[27]

The RtAPS comprises:

-

group psycho-education brief on:

-

the RtAPS and its aims and process (including confidentiality

issues and data use);

-

readjustment to family life (including reactions of partner,

children, and friends);

-

readjustment to work (including relationships with peers and

career decisions); and

-

health issues (including post-deployment fitness, and tobacco and

alcohol use).

-

a questionnaire, comprising the:

-

Deployment Experiences Questionnaire (including data on

operational temp and unit climate);

-

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10);

-

Traumatic Stress Exposure Scale – Revised (TSES–R);

-

Major Stressors Inventory – Revised (MSI–R); and the

-

Posttraumatic Checklist (PCL).

-

one-on-one semi-structured screening interview, which covers the

following (as a minimum):

-

introduction;

-

deployment experiences;

-

potentially traumatic events;

-

coping strategies;

-

current symptoms;

-

homecoming and adjustment issues;

-

screening questionnaire summary; and

-

psychoeducation.[28]

Post-Operational Psychological

Screening (POPS)

3.20

Post Operational Psychological Screening (POPS) is mandatory for all ADF

members who were eligible to receive RtAPS (regardless of whether they did or

not) and is usually conducted within three to six months of a member's return

to Australia from an overseas deployment. The POPS process aims to identify

individuals who have not reintegrated into occupational, familial, or social

functioning and/or are demonstrating signs of adverse post-trauma responses. The

POPS questionnaires and write-up are placed on the ADF member's psychology file

and Unit Medical Record. The POPS process comprises:

-

a questionnaire, comprising the:

-

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10);

-

Posttraumatic Checklist (PCL);

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT); and

-

additional Command and research questionnaires as approved by the

senior psychology asset for the services.

-

a one-on-one semi-structured psychological screening interview

that includes:

-

introduction;

-

review of the member's deployment experience;

-

homecoming;

-

reintegration;

-

current symptoms; and

-

psychoeducation.[29]

Special Psychological Screen (SPS)

3.21

A Special Psychological Screen (SPS) may be provided to individuals and

groups 'whose operational role routinely exposes them to intense operational

stressors, critical incidents, and/or potentially traumatic events while on

deployment'. The aim of the SPS is to aid the monitoring of the mental health

status of such individuals and groups. The SPS may be administered regularly

(every two to three months) and comprises:

-

a psycho-educational briefing;

-

a questionnaire comprising the:

-

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10); and the

-

Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS); and

-

a one-on-one psychological screening interview.[30]

3.22

The need for SPS is negotiated between commanders and mental health

professionals, and the completion of SPS does not negate the necessity for

RtAPS or POPS. Furthermore, the SPS can only be conducted by a mental health

professional.[31]

Critical Incident Mental Health

Support (CIMHS)

3.23

Critical Incident Mental Health Support (CIMHS) is initiated when a

'critical incident' has occurred, such as deployed members being exposed to

potentially traumatic events.[32]

The activation and timing of the CIMHS is determined by the Commanding Officer

in consultation with the CIMHS coordinator (the most senior CIMHS-trained

mental health professional available). The CIMHS process comprises a number of

activities across three stages:

-

provision of social support, and psychological first aid (PFA) if

necessary;

-

provision of psychoeducation and administration of psychological

screens (Acute Distress Disorder Scale and Mental Status Examination) to

facilitate the identification of individuals at risk of psychological injury

and initiation of referral for further assessment and treatment;

-

follow-up (Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10),

Posttraumatic Checklist (PCL) and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).[33]

3.24

The timing of the follow-ups generally take place between three and six

months after the initial screen. According to the CIMHS database, a total of

354 individuals received a CIMHS initial screen between March 2012 and March

2014, with the majority of those 354 individuals also having completed a

follow-up screen.[34]

Informal screening

3.25

The Australian Defence Force Mental Health Screening Continuum Framework

Repot (MHSCF Report), conducted by the Australian Centre for Posttraumatic

Mental Health in 2014, highlighted the importance of informal screening for

mental ill-health and noted that formal screening is not intended to replace

informal processes, but rather, to complement them:

These informal processes may include families, friends, and

peers helping the member identify that he or she has a problem. This type of

informal screening is of great relevance in organisations such as the ADF that

place a high emphasis on "looking after your mates". A commander,

manager, or representative can also order a member to undergo psychological

assessment or gain psychological support through administrative referral.

Additionally, a Medical Officer (MO) can refer a member for psychological

support or assessment through medical referral. Of course, members may also

self-identify that they are experiencing mental health difficulties and request

assistance. These informational processes of identifying members who are

struggling with psychological adjustment issues are of primary importance in

early detection and access to care.[35]

3.26

Aspen Medical emphasised the importance of maintaining multiple ways to

identify and bring ADF members to treatment, noting that 'the multi-faceted

strategy taken by the ADF appears to be working'. It noted that in the ADF 'if

one method does not identify a case an alternative method is highly likely to'.[36]

Family involvement in

identification and screening

3.27

The importance of involving the ADF member's family in the

identification and treatment of mental ill-health was raised by a number of submissions.[37]

Australian Families of the Military Research and Support Foundation (AFOM)

asserted that families of ADF members are often the first to become aware of

signs of mental ill-health and called for family to be involved in

post-deployment screening processes.[38]

3.28

Aspen Medical noted that its practitioners strongly supported greater

involvement of a supportive family member in the treatment of mental health

conditions for ADF members.[39]

Furthermore, it found that seven per cent of referrals for ADF members to

mental health professionals were from a member's family, commenting that 'the

involvement of family also suggests that the ADF and JHC messaging to members'

partners, spouses and the broader community are having an effect'.[40]

3.29

The Australian Association of Social Workers highlighted the importance

of family involvement and assessment of family dynamics in the identification

and assessment of mental ill-health, noting that 'without a clear understanding

of family dynamics, including stresses and strengths, mental health assessments

will miss important information relevant for treatment and counselling

outcomes':

An early family assessment is not only crucial in

understanding the impact of a psychological diagnosis on the service personnel

and their family, but also means that important supports can be mobilised

early. It also alerts the clinician of areas in which clinical treatment might

be undermined by family dynamics. Often treatment is disrupted by events in the

external environment. Social work assessments that include a family assessment

and an assessment of other psychosocial factors are highly valued in mental

health teams.[41]

3.30

In 2011, the Family Sensitive Post Operational Psychology Screens

(FSPOPS) were trialled with Mentoring Taskforce-2 (MTF-2) in Darwin and with

MTF-3 in Townsville in 2012. The FSPOPS project involved training Defence

psychology staff in family sensitive practices that can be applied to the POPS

process. ADF members undertaking their POPS in Darwin and Townsville were invited

to bring an adult family member to their POPS to 'provide an opportunity to

discuss issues and challenges that may arise post-deployment'. This opportunity

was promoted by Regional Mental Health Teams and Command elements.[42]

3.31

Defence informed the committee that only a very small number of the

hundreds of ADF members deployed with MTF-2 and MTF-3 brought family members to

their POPS during the trial period. The majority of ADF members who did not

bring a family member to their POPS indicated that they 'felt no issues existed

that warranted discussion with a family member' or 'simply did not want to

bring a family member'. However, those family members who did participate

indicated that the experience was 'very good' and that they would participate again

if offered.[43]

3.32

Defence advised that the outcome of the trial 'suggests that this

initiative was not one that appealed to the wider ADF audience' and that, as

such, the trial was not extended or developed into business as usual. However,

Defence assured the committee that it remains committed to a family sensitive

approach to screening and mental health and rehabilitation service delivery:

The trial has not been extended or developed into business as

usual, but the concept of ensuring that family related matters and family

sensitive questions are raised during Post Operational Psychology Screens by

psychology staff has been adopted. This has resulted in a more family focussed

approach to operational mental health screening of ADF members.

Defence recognises the importance of engagement with and

support to families of members who are ill or injured. Defence is focusing on

developing services and processes that support a family sensitive approach to

mental health and rehabilitation service delivery, to promote positive outcomes

for members and families. These processes include inviting family attendance at

health assessments (where appropriate and with member consent), inviting

attendance at psychosocial workshops and information sessions, and referral to

available programs and services as appropriate. Resources available to family

members are also reinforced through unit family days and direct communications

from support services such a Defence Community Organisation or Veterans and

Veterans Families Counselling Service.[44]

Privacy

3.33

Some submissions noted that, linked to the stigma associated with mental

ill-health, many ADF members were not comfortable disclosing mental health

issues due to concerns that their privacy would not be respected and they would

be subject to ridicule.[45]

The Australia Psychological Society noted that:

Members report that stigmatisation may occur during service

within the immediate base community and the larger organisation. This stigma

and issues with confidentiality reportedly create difficulties particularly at

the lower level of command where information about confidential disclosures [of

mental ill-health] reportedly is disclosed to others in the base community.[46]

3.34

Defence assured the committee that it is required to comply with the

provisions of the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act) and the Australian

Privacy Principles. Health Directive 610 Privacy of health information of

Defence members and Defence candidates outlines the policy regarding

the collection, use, and disclosure of health information in Defence by health

professionals, commanders, managers, and members. A Health Information Privacy

Notice, which details how health information is collected, used, and disclosed,

is available to all ADF members on the Defence Intranet.[47]

3.35

ADF members must give consent for their personal health information to

be used or disclosed in all but exceptional circumstances (as defined by the Australian

Privacy Principles).[48] Exceptional circumstances include when use

or disclosure is necessary to lessen or prevent a serious threat to an ADF member's

life, health, or safety; or a serious threat to public health or public safety,

including in military workplaces and safety critical areas such as deployment.[49]

3.36

Defence informed the committee that health information is primarily

collected by Defence health practitioners 'in order to clinically manage and

treat a Defence member's health on an ongoing basis'. This health information

is shared between all treating health professionals in order to provide

coordinated health care services, particularly when ADF personnel are receiving

mental health care. Health information can also be shared with external health

care providers with the consent of the ADF member.[50]

3.37

Defence stated that Defence health professionals are obliged to keep

commanders and managers informed of the health status of ADF personnel to

enable them to manage the workplace and operational impact of an ADF member's

health condition. The health information provided is limited to information

'that enables a member's administrative management to be coordinated with their

health support and rehabilitation management plans', unless the ADF member

consents to more information being provided.[51]

Commanders' need to know and

members' right to privacy

3.38

Some submissions highlighted the conflict between commanders' need to

know about the mental health of their personnel and ADF members' right to privacy.[52]

The Inspector General of the Australia Defence Force (IGADF) noted that

compliance with Privacy Act requirements and the confidentiality obligations of

members of the medical profession can 'sometimes impede the reasonable sharing

of medical and psychological information concerning a member that may be

important for their better management by their chain of command or other

Defence agencies with responsibilities for members' welfare and safety'.[53]

3.39

The Alliance of Defence Service Organisations (ADSO) asserted that

commanders 'should surely have the right to know, and medical professionals the

right to inform [them]', regarding any medical (mental or physical) problems

that could compromise a mission or the safety of other ADF members. Further,

the ADSO called for the application of the Privacy Act, as it applies to ADF

members, to be reviewed:

The bargain struck between the ADF and the individual should

be that the ADF provides comprehensive health care free of charge because it

has to have a solid base of confidence that the individual meets the fitness

standards demanded by the mission. This should mean that the individual

surrenders that part of the right to privacy that is relevant to the mission,

as he does in other areas, such as military security. Indeed it could be argued

that physical and mental fitness is, at least in part, a security matter. ADSO

urges that this aspect of the application of the Privacy Act to members of the

ADF to be reviewed as a matter of urgency.[54]

3.40

The IGADF advised the committee that some ADF members will choose to

seek assistance from sources outside of the ADF for mental ill-health to

prevent the chain of command from accessing information about the member's

mental health. Such members fear putting their career, job categorisation, or

deployment opportunities at risk. The IGADF described this as a 'catch-22

situation for Defence', for any attempts to relax patient confidentiality

requirements to better identify and address mental ill-health might further discourage

members from seeking assistance/treatment for mental ill-health within the ADF:

...the reluctance of some members who are aware they may have a

medical or mental health problem to advise their chain of command or seek help

from Service health authorities for fear of putting their career, job

categorisation, or deployment opportunities in jeopardy. This can sometimes

create a catch-22 situation for Defence where members may be minded to seek

assistance from private sources in order to preserve confidentiality of their

condition. The catch-22 arises where any relaxing of patient confidentiality

requirements within Defence might potentially have the unintended effect of

encouraging members to seek help outside the Service system.[55]

3.41

The RSL also commented on ADF members' reluctance to disclosing mental

health concerns, noting that some members choose not to disclose symptoms to

avoid medical downgrading, which may interfere with their deployment or result

in discharge. The RSL stated that 'members are well aware of the financial

incentives associated with deployment and the need to be physically fit and

mentally fit to deploy'.[56]

The RSL, pointing to an opinion expressed in an interview with Dr Andrew Khoo,

asserted that:

...encouraging Defence members to seek early treatment for

mental ill-health will not be successful until Defence allows members to be

treated and continue in their career with Defence. Until then, serving members

will continue to believe disclosure of mental ill-health will threaten their

Defence career.[57]

3.42

Defence acknowledged that there are times when 'despite all the best

efforts on rehabilitation...people will end up inevitably being discharged',[58]

but that 'of the 869 individuals with a mental illness who completed a rehabilitation

program, a total of 420 or 52 per cent are recorded as having a successful

return to work at the end of their rehabilitation program'.[59]

3.43

The adequacy of mental health services is discussed in greater detail in

Chapter 4 of this report. Stigma surrounding mental health and other barriers

to disclosure is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5.

Family access to members and

veterans mental health records

3.44

Slater & Gordon Lawyers called for a review of the Privacy Act,

asserting that details of mental health records should be released to families

if the ADF member or veteran presents symptoms of mental illness that pose an

immediate risk to personal safety, such as self-harm and suicide attempts.

In such situations, the ADF must have the authority to

release certain details of a serviceman or woman's mental health record to

their families in order for them to assist in providing support...the Committee

must do everything in its power to ensure that families do not have to endure

the heartbreak of losing a loved one from a potentially treatable mental

illness.[60]

3.45

Slater & Gordon pointed to the family of 27 year-old Navy Sailor

Stuart Addison, who took his own life in 2002. His family have been campaigning

for the next of kin to be contacted immediately by a member's commanding

officer in circumstances where suicide attempts or self-harm is evident.[61]

3.46

One submitter called for families to be notified of suicide attempts.

The submitter told the committee of their experiences strugglingly with mental

ill-health and suicide, stating that their first attempted suicide took place

while still a serving member. The submitter noted that 'suicide prevention

takes inside information' and called for the introduction of a 'Family in

Crisis Action Plan' to be triggered in the case of a suicide attempt:

...when a Veteran attempts Suicide, that contact is immediately

made with the Veteran Family. Implementation of an Action Plan should include

ESO Contact, Family Social Worker Contact to be able to assist any needs of the

family during the Crisis. Also emergency Crisis care for children should be

initialised and paid for by DVA whilst the Veteran is hospitalised and in

treatment so that the partner or designated carer or eldest child can

participate in the support and information process with the Veteran. "It

must not be a journey taken alone by the Veteran."[62]

3.47

Defence acknowledged these concerns but asserted that its focus is on ensuring

ADF members are 'afforded appropriate privacy protections' while encouraging

them to involve families and support networks in their mental health safety

plan, treatment and recovery:

Defence recognises that there have been concerns expressed by

family members about what information can be disclosed to them and how

disclosing certain health information could have resulted in better mental

health outcomes, or in extreme situations prevented a death by suicide.

Defence's focus is on ensuring that ADF personnel are afforded appropriate

privacy protections while encouraging the member to involve their families and

support networks in their mental health safety plan, treatment and recovery by

sharing their health information should they wish to do so.[63]

Recordkeeping for ADF members

3.48

Defence informed the committee that 'health-related record keeping is

managed in accordance with the Defence Records Management Policy and the

relevant legislation'. Defence also advised that it is currently reviewing its

health records management policy to provide a 'single policy for all ADF

personnel that receive health services from Defence'.[64]

However, the management of ADF mental health records has been criticised for a

number of decades and have been the subject of a number of inquiries and

audits.[65]

3.49

The committee received a number of submissions commenting on the

difficulties with accessing health records and the complications that can arise

when a veteran is making a claim if health records are incomplete or

inaccurate.[66]

Furthermore, comprehensive health records of veterans can be even more

challenging, as noted by Mr Robert Shortridge: 'maintaining records of those

ex-service personnel once they have left the ADF will be very difficult as

there is no compulsion for them to identify themselves as ex-service personnel

or veterans'.[67]

3.50

Walking Wounded described ADF recordkeeping as a 'weak area', noting

that, despite good recordkeeping policies, 'human error, tiredness, inattention

and carelessness' lead to incidents being reported 'badly or not at all':

Anecdotally, all soldiers have stories of how a particular

incident was recorded badly or not at all, including events where injuries

occurred. This often leaves the record incomplete or disjointed, particularly

where operational imperatives take precedence. In addition, the retrieval of

records pertaining to a specific incident some years in the past is often

almost impossible, owing to personnel turnover and the reasons cited above.

When an ADF member is no longer an ADF member, the task gains a further degree

of difficulty.[68]

3.51

One submitter noted that a complete and accurate record of a member's

mental health is dependent on the member disclosing their mental ill-health,

something that many may be reluctant to do.[69]

Defence e-Health System

3.52

In 2009, Defence launched the Defence eHealth System (DeHS) (originally

called the Joint eHealth Data and Information System). The key features of the

DeHs include:

-

Primary Care System (PCS): an eHealth care system used to record

all clinical, dental, mental health, and allied health consultations,

treatments and findings;

-

DeHS Access: an online patient- accessible summary of each

patient's eHealth record; and

-

DeHS Reporting: a suite of reporting tools available to report on

individual or corporate information requirements.[70]

3.53

These three features are intended to provide a clinical management tool

'that enables safe and quality health care for the ADF member'. The DeHS

business case noted that the system would:

-

inform ADF Commanders of the readiness for operational

deployments of individuals and Force Elements;

-

contribute to the generation of health performance and work

health and safety metrics to support the management of resources as well as

planning and accountability; and

-

provide for effective health management after an ADF member's

discharge by facilitating the transfer or access of an ADF member's health

record by DVA as part of ongoing care and/or to inform compensation

determinations.[71]

3.54

Furthermore, the DeHS is intended to complement the civilian National

e-Health Strategy and link with the national Personally Controlled Electronic

Health Record:

The Joint eHealth Data and Information (JeHDI) Project [now

called DeHS] will facilitate the provision of one electronic health record for

ADG personnel, from recruitment to discharge, then through to management in

other agencies...[DeHS] is building the capability to interact with the National

Personal Controlled Electronic Health Record (PCEHR) for the interchange of

health information across private and public health systems. Members will be

able to consent to participation in the PCEHR system while in Defence or when

they discharge.[72]

3.55

Defence advised that the DeHS was implemented within all Joint Health

Command Garrison health centres on 11 December 2014 and that the DeHS project

to implement the system on-board ships is scheduled for implementation on the

"First of Fleet" by June 2016, with subsequent roll out to the

remainder of the fleet in accordance with the Fleet schedule.[73]

3.56

Defence informed the committee that it is expected that ADF members will

be able to access their e-Health record via the internet portal from the

second-half of 2015. ADF members will be able to view a summary of their health

record, view recent and scheduled appointments, and complete health

questionnaires in preparation for a mental health consultation. ADF members will

be able to access routine mental health questionnaires and screening tools

online, which, Defence advised, will notify mental health professionals if the

results of a questionnaire need to be responded to urgently.[74]

3.57

Defence explained that the data analysis and reporting functions of DeHS

will allow Defence to 'target reporting for specific mental health

presentations and disorders and that the DeHS system has minimised the use of

paper records, with the majority of ADF members receiving primary health care

treatment through a Garrison Health Organisation'. All mental health and

psychology records created prior to the implementation of DeHS will continue to

be available. In addition, as legacy systems are decommissioned, all pertinent

records will be transferred to Objective (the approved restricted Defence

electronics records management system).[75]

3.58

Aspen Medical reported that it received a number of positive comments in

its initial survey regarding the benefits of the new DeHS, with 39 per cent of

respondents agreeing that the DeHS has improved the availability of relevant

documents and only 18 per cent disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Aspen

Medical noted that many positive comments also expressed a degree to

frustration with DeHS.[76]

Hospital admissions, external

referrals, and fatalities

3.59

Defence explained that the DeHS incorporates ADF members' external

mental health provider reports, ensuring that a member's health record reflects

a continuous view of their mental health care that can be monitored by Defence:

The Defence e-Health System allows for the timely monitoring

of external mental health provider reports by the local Mental Health and

Psychology Section, and these reports are reviewed at the regular

multidisciplinary Case Review meetings to ensure that treatment is meeting the

needs of the member, and that the member remains engaged with the external

provider. The external reports are then electronically appended to the member's

health record via Defence e-Health System in order to provide a continuous view

of the member's mental health care.[77]

3.60

If an ADF member requires admission to an external treatment facility as

an inpatient, either as an emergency or planned admission, the referral is

noted in the member's e-Health record and a Notification of a Casualty

(NOTICAS) and a Medical Casualty (MEDICAS) are raised. The NOTICAS and MEDICAS

notifications allow command, health, and welfare agencies to ensure that the

member's occupational, health, and domestic needs are met and that the member's

family is supported during the admission. Once discharged, a discharge summary

report is provided to the treating garrison health facility and uploaded into

DeHS. Defence advised that the admission of an ADF member to an external

treatment facility for mental health in-patient treatment is regularly followed

up by the local Mental Health and Psychology Section.[78]

3.61

Defence advised that, following the death of a serving ADF member, the

e-Health record is moved from the DeHS to Objective, the approved restricted

Defence electronic record management system for archival purposes. The archived

record can be accessed by Defence health care professionals and member's

families can request access 'using normal Defence record access request

processes'.[79]

Suspected or confirmed suicide

3.62

Defence informed the committee that the release of post mortem results

and coronial inquiry outcomes remains at the discretion of the coroner and are

not routinely provided to Defence unless pursued by the ADF Investigative

Service. Defence noted that post mortem updates can be made to an ADF member's

DeHS record upon receipt of a death certificate or coronial record but that

this is not mandated:

Clinicians do not currently update the record regarding

speculative diagnosis or causal finding. The finding of suicide has to be a

post mortem update and this is permitted to be added to the record by

authorised users. The content of these updates/entries are not mandated in any

way. If Defence does receive a death certificate or coronial record it will be

added to the record.[80]

3.63

Defence advised that Joint Health Command maintains a database, separate

to the DeHS, of suspected or confirmed deaths as a result of suicide since 1

January 2000. Suspected or confirmed deaths as a result of suicide are included

in the database on the advice of the ADF Investigative Service and/or the

findings of State/Territory Coroner Reports.[81]

Medical records during deployment

3.64

Aspen Medical reported that that it 'is rarely easy to find relevant

clinical information collected or recorded in-theatre' regarding mental

ill-health or potentially traumatic incidents:

Just over 75 per cent of respondents found that it is usually

not easy to find clinical information on incidents that occurred in theatre. In

many instances the trigger event for a mental health condition may not have an

immediate impact on the [member], so in effect there is no clinical record of

the event occurring.[82]

3.65

Aspen Medical noted that some clinicians suggested that Medical Officers

(MO) and Mental Health Professionals (MHP), when treating a member, should be

given access to the member's commander when the traumatic event occurred which

might have caused mental health problems. This would allow the MO and MHP to

understand the events without forcing the member to 'relive' them.[83]

3.66

A number of submissions highlighted the importance of accurate and

detailed records when lodging a claim with DVA.[84]

This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5 of this report.

Identification and screening of mental ill-health during transition

3.67

The ADF does not currently conduct post-transition screening. The

Defence Community Organisation emails a post-separation survey to all ADF

members who have been discharged for at least three months. The post-separation

survey asks questions regarding the separation experiences, the member's chosen

post-transition occupation, and their perceptions of support received around

transition.[85]

3.68

The MHSCF Report noted that screening at discharge was challenging due

to transitioning members' concerns that identification of mental health

problems might delay their discharge:

During the discussions about timing, the process at

transition was raised. Both senior leaders and health professionals noted that

screening at transition was challenging as members may be concerned that

identifying mental health problems may delay their discharge. There were some

suggestions that, if screening were to be included in the transition process,

it should occur around six months prior to transition in order to be able to address

any concerns without the risk of delaying the member's leave.[86]

3.69

Discharge and transition from the ADF to civilian life with be discussed

in greater detail in Chapter 6 of this report.

Veteran Mental Health Strategy

3.70

The Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) is responsible for the

development and implementation of programs to assist the veteran and defence

force communities. It provides administrative support to the Repatriation

Commission and the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission. It is

responsible for advising the Commissions regarding policies and programs for

beneficiaries as well as for administering these policies and programs. Mr Shane

Carmody, the Chief Operating Officer for DVA, advised the committee that mental

health is a priority for DVA:

Mental health is a priority for DVA and any suicide is a

tragedy, so we must do all we can to prevent it. As the committee knows,

funding for mental health treatment is demand-driven and is not capped. We

spend around $182 million annually on veteran mental health services, but our

focus remains on early intervention. If people are worried about how they are

feeling or how they are coping we encourage them to seek help early. There are

services and there is support ready and waiting to help.[87]

3.71

The Veteran Mental Health Strategy 2013-2023 outlines the

strategic framework to support the mental health and wellbeing of veterans. The

strategy lists six strategic objectives to guide mental health policy and

programs:

-

ensure quality mental health care, which puts the client at the

centre, is evidence-based, efficient, equitable, and timely;

-

promote mental health and wellbeing, addressing the diverse needs

of clients and barriers to help-seeking such as stigma;

-

strengthen DVA workforce capacity, ensuring a strong

understanding of military and ex-military experience, and knowledge of best

practice mental health interventions;

-

enable a recovery culture, reducing the stigma surrounding mental

health in the veteran and ex-service community and encouraging help-seeking and

support recovery;

-

strengthen partnerships, leading to improved service systems,

enhanced communication and coordination, efficient use of resources, and

opportunities for continuous feedback and improvement; and

-

build the evidence base, building capacity within the mental

health provider community and informing policy and program development.[88]

3.72

DVA described the focus of its mental health policy as 'firmly on early

intervention':

The benefits of early intervention are clear, both for the

veteran and their family. Recent Government budget initiatives further

highlight the commitment to treating mental health conditions. Over recent

years, significant funding has been invested in new initiatives aimed at

improving the mental health of veterans, from improved access to treatment and

counselling, through to improvements in the Department's management of clients

with complex needs, including those with mental health conditions. Further, the

Government is very focussed on improvements to reduce the time taken to process

compensation claims, a key early initiative.[89]

3.73

Mr Carmody reiterated this, stating that 'DVA's major focus is on early

intervention. This is the critical step in identifying and meeting the mental

health needs of the veteran community'.[90]

Identification of mental ill-health in veterans

3.74

Unlike ADF members, veterans are not required to be screened for mental

ill-health and veterans cannot be 'ordered' to seek treatment or assistance

when they display symptoms of mental ill-health. However, veterans can access

the ADF Post-discharge GP Health Assessment, a 'comprehensive health

assessment from their General Practitioner (GP)'. The scheme provides GPs with

screening tools for alcohol use, substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) and psychological distress 'to help GPs identify and diagnose the early

onset of physical and/or mental health problems'. The scheme is funded under

the health assessment items on the Medicare Benefits Schedule.[91]

3.75

Generally, DVA is made aware of a veteran's mental ill-health once a

veteran has lodged a claim. A number of submissions noted that this puts the

impetus for recognising and seeking treatment for mental ill-health on the

veteran.[92]

Walking Wounded commented that 'once a Defence member leaves the service, the

responsibility for overarching care falls foremost onto the individual and, if

he or she is lucky, close family members'.[93]

The Australian Psychological Society described this as a critical barrier to

identifying the scope of veterans' health needs:

Post discharge, veterans are unable to be identified by DVA

where they do not seek entitlements to pensions, compensation or treatment.

This creates critical barriers to identifying the scope of service-related

health and welfare issues and the demand for associated services. While DVA

advocates that there should be service pathways which operate under the 'no

wrong door policy' approach and maintains registration information about

veterans and current serving personnel who seek entitlements, in the absence of

such registration, there is little chance that ex-service personnel will seek

or receive the DVA funded treatment to which they are entitled.[94]

3.76

The Royal Australian Regiment Association (RARA) noted that 'many

veterans leave the ADF without lodging any claims for disability but they

develop problems later in life and who are, or consider themselves to be

healthy, may feel a little embarrassed about seeking help'. The RARA asserted

that 'DVA is the appropriate sponsor for embracing these people' and called for

a review of the processes for identifying and monitoring veterans mental

health:

There needs to be a major conversation and paradigm shift in

the mindset of the Government and Parliament, Defence Department that includes

DVA, veterans, and the broader community as to how we can best keep track of

all our veterans well after their service and not just those who have become

DVA clients.[95]

3.77

The RSL also noted that many veterans are reluctant to respond to early

symptoms of mental ill-health, stating that 'ignoring symptoms and not seeking

help can sometimes go on for eight to 10 years after discharge':

We are told by many veterans and their families that symptoms

are ignored for a variety of reasons, including pride, learned responses in

Defence to ignore emotions and keep going, the financial incentives associated

with deployment, a belief that they are not the problem, and a lack of

knowledge of the symptoms of mental ill-health.[96]

3.78

DVA acknowledged these concerns, noting that 'the challenge for DVA is

to encourage clients to seek help early if they are worried about how they are

coping or feeling, and not wait until the symptoms become overwhelming'.[97]

Mr Carmody advised the committee that DVA is working to raise awareness of its

services, assisting transitioning members, and encouraging the early lodgement

of claims:

To ensure that people know about our services and the support

that we can provide, the department secretary now writes to all 6,000 or so ADF

personnel who separate each year. This letter outlines what DVA can do for them

and that we are here to help them if and when required. Even so, around 25 per

cent of separating ADF personnel opt out of receiving information from DVA.

DVA's on-base advisory service has developed into a very important service,

providing advice and support as well as encouraging the early lodgement of

claims. DVA now has an on-base presence at over 44 bases around the country. In

2013-14, our on-base service responded to over 13½ thousand inquiries—an

increase of over 4½ thousand on the previous year.[98]

3.79

DVA asserted that it is using 'new and innovative ways' to reach out to

contemporary veterans and encourage them to take action early to address any

mental health concerns. DVA provides a single mental health online portal, known

as 'At Ease', which brings together all of its online products. These include:

self-help and supportive phone apps; videos of veterans talking about their

mental health recovery; and information about professional support and

treatment options.[99]

3.80

DVA advised that it also works in partnership with the ex-service

community to implement health and wellbeing programs, which focus on seeking

help when needed and healthy lifestyle behaviours such as healthy eating, social

connectedness and physical activities.[100]

The RSL stated that it is working together with DVA and other ex-service

organisations (ESOs) to reach out to veterans who are struggling with mental

ill-health:

The RSL, other Ex-Service Organisations (ESOs) and DVA are

working hard to 'pick up the pieces' and intervene as soon as anyone in

difficulty is brought to our attention. Informal networks of support, both

face-to-face and online are extensive. There is a collective goodwill and

concern for mates that characterises this sector (among both current and

ex-serving members) and together many veterans have saved the lives of others

in trouble.[101]

3.81

However, the RSL warned that 'relying on informal networks alone can be

fraught with potential problems'.[102]

Veterans identification system

3.82

The RARA and the Alliance of Defence Service Organisations called for

the introduction of a veteran identification number or identification card to

assist in the collection of data regarding the health and wellbeing of veterans

who are not DVA clients.[103]

The RARA noted that:

In recent times, the media has highlighted the incidence of

veterans being incarcerated and sadly self-harm and suicide. These three issues

raise the possibility that many of the homeless, veterans in the prison system

and self-harm are invariably in this state due to mental health issues. Too many

veterans are falling through "the cracks" because we don't know who

or where they are.[104]

3.83

The Veterans Care Association noted that the provision of a veteran

identification card would 'add dignity and honour the service of all veterans'.[105]

The ADSO asserted that the introduction of a veteran identification card would

allow support services such as medical, ambulance, police and government

agencies to better identify veterans:

One of the principle requirements of support is being able to

identify veterans. The need for a single identifier to follow and ADF through

service and into post ADF life is becoming more evident. It has the support of

the AMA [Australian Medical Association]. It should cover all serving and

former ADF members.

A National Veteran Identity Card could fulfil this need and

would allow support agencies (medical, ambulance, police, government agencies,

etc.) to identify and allocate veterans to the appropriate assistance needed.[106]

3.84

Mr Carmody advised the committee that DVA is working with Defence to

implement a single identification number but that there are a number of

complications including non-ADF DVA clients (such as war widows) and privacy

issues:

We are also trying to work with Defence on this single number

but, as I have said, we have 340,000 clients and a large number of our clients

do not have ADF service; they are war widows. So 60,000 to 70,000 people do not

have a Defence number. We also have the situation where, particularly, our

World War II and or Korean veterans had different prefixes on the numbers that

they were allocated when they were in service, by state. There were different

prefixes by gender. Our history of engagement with the numbering system is a

very long one, and there is a range of very different numbers. We are in the

process of working with Defence to try and resolve that in looking forward;

however, in terms of all of our current client base, we need a very complex

system of cross-referencing the various numbers that they might have been

given, including DVA numbers. It is not a straightforward matter of just giving

everyone a number, because as I said, a large number of our clients will not

have one to start with.[107]

3.85

The records required for DVA claims, and the systems under which these

records are stored and accessed, is discussed in Chapter 5 of this report.

Committee view

3.86

The committee acknowledges the challenge of ensuring that ADF members'

duties do not detrimentally affect their health; that ADF members can undertake

their duties without compromising the safety of themselves or others; and that

the ADF as a whole maintains it operational capability. The committee commends

the ADF for its mental health and wellbeing strategy and acknowledges the

significant achievements that it has made since the introduction of its first

Mental Health Strategy in 2002. Early identification and treatment of mental

ill-health is crucial for ADF members struggling with mental ill-health to

achieve the best possible outcomes as well as ensuring that the ADF maintains

operational capability.

Identification of mental ill-health

in the ADF

3.87

The committee is satisfied that the RtAPS, POPS, SPS, and CIMHS

screening processes, together with informal screening, are useful tools for the

early identification of mental ill-health among ADF members who have been

deployed. However, the committee is concerned that similar care is not taken to

identify mental ill-health among ADF members who have not been deployed. As

discussed in

chapter 2 of this report, the findings of the MHPW study indicated that there is

no significant link between deployment and an increased risk of developing

PTSD, anxiety, depression or substance abuse disorders. Yet, despite this, mental

health screening appears to focus primarily on identifying mental ill-health in

members who have been deployed.

3.88

The committee is encouraged by the referral pathways reported by Aspen

Medical and the high percentage of self referrals and referrals from medical

officers, which indicate that mental health policy regarding the shared

responsibility between commanders, individuals, and clinicians for the

identification and early treatment of mental ill-health is working. However,

the committee believes that regular formal and informal screening of ADF

members, regardless of their deployment status, will improve the early

identification and treatment of mental ill-health in the ADF.

3.89

The committee acknowledges that ADF members may be concerned about the potential

impact that the discovery of mental ill-health may have on their careers.

Nonetheless, the committee believes that the early identification and treatment

of mental ill-health is significantly less likely to negatively impact a

members' career, both within and beyond the ADF, than mental ill-health that is

left untreated. Furthermore, annual screening would provide a regular

opportunity for ADF members to pause and consider their mental health as well

as providing a forum to express concerns that they might have without the

member needing to initiate an appointment with their medical officer or

psychologist.

Recommendation 1

3.90

The committee recommends that Defence conduct annual screening for

mental ill-health for all ADF members.

Privacy and disclosure of mental

ill-health

3.91

The committee acknowledges ADF members' right to privacy and the stigma

and concerns regarding career prospects that might cause ADF members to conceal

mental ill-health from their commanders and colleagues. However, the committee

recognises that the ADF members' right to privacy must be carefully balanced

with commanders' responsibilities to ensure that ADF members' duties do not

detrimentally affect their health, that ADF members can undertake their duties

without compromising the safety of themselves or others, and that the ADF as a

whole maintains it operational capability.

3.92

The committee is satisfied that the provisions of the Privacy Act and

the Australian Privacy Principles appropriately govern the collection, use, and

disclosure of health information in the ADF. The committee notes the concerns

raised by the IGADF and the calls from ADSO and Slater & Gordon Lawyers for

the Privacy Act, as it applies to ADF members, to be reconsidered. However, as the

root of these concerns appears to be ADF members' reluctance to disclose mental

ill-health, the committee does not believe that stricter disclosure laws or a

lessening of ADF members' rights regarding privacy will assist in the early

identification and treatment of mental ill-health. More effort should be given

to addressing the stigma of mental ill-health in the ADF than tampering with

privacy laws.

Recordkeeping

3.93

The committee commends the goals of the DeHS, which, once fully

implemented and integrated with the civilian National e-Health Strategy, will

provide ADF members and veterans with an accurate, easily accessible, and

continuous health record. The committee also notes that Defence is currently

undertaking a review of its health records management policies to consolidate a

'single policy for all ADF personnel that receive health services from

Defence'.

3.94

Accurate health records are vital in ensuring that ADF members receive

informed and targeted treatment for mental ill-health as well as being a

crucial element in the DVA claims process. As such, the committee is concerned

by evidence from medical officers and mental health professionals that it

remains difficult to find relevant clinical information collected or recorded

during deployment.

3.95

The committee acknowledges that there are a range of factors that can

impact accurate recordkeeping, especially on deployment, and that accurate

recordkeeping of ADF members' mental health may also be inhibited by reluctance

to report mental ill-health. However, it is essential that mental ill-health

and potentially traumatic events are accurately recorded during deployment and

that medical officers and mental health professionals can easily access these

records when treating ADF members. It is also important to ensure that veterans

and DVA can easily and quickly access these records when assessing claims.

Recommendation 2

3.96

The committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office

conduct an audit into the scope and accuracy of recordkeeping of relevant

clinical information collected or recorded during deployment regarding mental

ill-health or potentially traumatic incidents.

Identification of mental ill-health

in veterans

3.97

The committee commends DVA for its 'At Ease' online portal, which

provides comprehensive information regarding mental ill-health to ADF members,

veterans and their families. The committee recognises that veterans are private

individuals who, unlike ADF members, cannot be ordered to undergo mental health

screening or ordered to seek treatment or assistance when they display symptoms

of mental ill-health. DVA is limited in its ability to identify or monitor

mental ill-health in veterans to those veterans who have sought assistance or

made a claim with DVA.

3.98

The committee acknowledges these limitations and notes the calls for DVA

to monitor the health of veterans who have not made a claim. However, any move

to monitor veterans without their consent would constitute a significant breach

of privacy. Nonetheless, whilst engagement with DVA must be initiated by the

veteran, the committee acknowledges that more must be done to encourage

veterans to seek assistance early and to make the process for seeking

assistance simple and swift.

3.99

The committee is very concerned regarding the piecemeal identification

systems for veterans; more must be done to ensure continuity of identification

of veterans, regardless of whether they are clients of DVA. The committee

acknowledges that DVA is working with Defence to implement a single

identification number between the two departments, however the committee

believes that all veterans should be provided with a universal identification

number and identification card that can be linked to the veteran's service and

medical records and utilised by both Defence and DVA, as well as other services

such as the those offered by the Department of Health and Department of Human

Services. All ADF members should be issued with a veteran identification number

and identification card upon discharge. All current and future clients of DVA

should be issued with this number and card and veterans who are not currently

clients of DVA should be actively encouraged to register for the veteran

identification number and identification card.

Recommendation 3

3.100

The committee recommends that all veterans be issued with a universal

identification number and identification card that can be linked to their

service and medical record.

3.101

The ADF Post-discharge GP Health Assessment scheme is an

important tool for the early identification and treatment of mental ill-health;

however it too relies on the veteran to initiate. The DeHS (once fully

implemented and integrated with the civilian National e-Health Strategy) should

provide veterans with an accurate, easily accessible, and continuous health

record. This should ideally allow GPs and other health professionals to

identify that their patient is a veteran as well as allowing them to view

records regarding any mental ill-health concerns or exposures to potentially

traumatic events that may have occurred during the veterans' service.

3.102

Furthermore, annual reminders through the e-health system prompting GPs

to suggest the veteran undergo ADF Post-discharge GP Health Assessment

would encourage veterans to engage with the scheme or even simply provide an

opportunity for veterans to discuss any mental health concerns with their GP. In

the meantime, GPs should be encouraged to promote the ADF Post-discharge GP

Health Assessment to all veterans.

Recommendation 4

3.103

The committee recommends that the Department of Health and the

Department of Veterans' Affairs ensure that e-health records identify veterans

and that GPs are encouraged to promote annual ADF Post-discharge GP Health

Assessment for all veterans.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page