Coordinating law enforcement across jurisdictions

2.1

Cybercrime is a global challenge, and any effective response requires

close coordination between law enforcement agencies across multiple international

jurisdictions. As the International Association of Prosecutors—Global Prosecutors

E-Crime Network (GPEN) stated, the central problem for law enforcement relates

to the problem of jurisdiction and the borderless nature of the internet:

Nearly every cybercrime will involve more than one jurisdiction

and therefore require some form of international cooperation. In cybercrime

cases you can have parallel or competing jurisdictions. There is the need for

clarity regarding jurisdiction some countries have domestic laws with

extrajurisdictional effect; and will limit the assistance they will give to

another country on a matter if they have a jurisdictional claim or interest. If

you look also at the different legal, investigative and prosecution systems and

the fact that some countries will not extradite their own nationals. It can

become very complicated and you can understand why countries require rules on

negotiating jurisdiction.[1]

2.2

This borderless nature of cybercrime means that no country can fully

protect itself against cybercrime without the help of law enforcement in other

countries. It is therefore necessary for all countries to have law enforcement

agencies, prosecutors and judges who understand the nature of cybercrime and

are able to cooperate on investigations and prosecutions of these crimes. As

GPEN noted:

ICT criminals typically hide in countries that are less

developed, where the law enforcement personnel, prosecutors and judges are less

efficient in the investigation and prosecution of ICT offences.[2]

International law enforcement arrangements

2.3

Australia is party to several inter-jurisdictional treaties, alliances

and other mechanisms that aim to facilitate international cooperation in

relation to the investigation of criminal activity enabled by new and emerging

technologies.

Council of Europe Convention on

Cybercrime (Budapest Convention)

2.4

Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest Convention) is the

leading, binding international instrument directed at cybercrime. It sets out

offences that criminalise ICT-offending, and encourages effective international

cooperation which is needed not only between governments but also with

industry. The Australian government announced in 2010 that it would take steps

to accede to the Budapest Convention. It came into force in Australia on 1

March 2013.[3]

2.5

Australia's accession to the Budapest Convention helps to improve the

ability of Australian law enforcement agencies to work effectively with their

overseas counterparts. The Budapest Convention aims to:

-

harmonise domestic legal frameworks on cybercrime;

-

provide for domestic powers to investigate and prosecute

cybercrime; and

-

establish an effective regime of international legal cooperation.[4]

2.6

Ms Esther George, Lead Cybercrime Consultant, International Association

of Prosecutors, noted how many non-European countries, including Australia,

have now adopted the Budapest Convention, increasing its effectiveness in

establishing principles for cybercrime offences:

...the Council of Europe cybercrime convention, which, although

it began in Europe, has actually spread and taken over quite a few countries.

They have about 56 countries as signatories now, and that includes Australia,

US, Turkey, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Israel, Japan, Mauritius, Senegal,

Sierra Leone, Tonga and the Philippines. I understand that Tunisia has recently

been invited to join....The reason that I think this convention is very good is

not just because I'm a Council of Europe expert...but also because the Council of

Europe convention is the only treaty you have that actually deals with [it].

It's been around since 2001 and it covers what I think are the main pillars

that need to be covered. It sets out the offences, and you've got countries

that have not signed up to the convention that actually have taken on board the

principles in their legislation and they've actually criminalised the

offences.... It brings back the idea that what you need for international

cooperation is for every country to criminalise the same offences.[5]

Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties

2.7

Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) are agreements between

governments that facilitate the exchange of information relevant to an

investigation occurring in at least one of those countries. They impact on the

way that a user's data is shared with foreign governments for criminal

investigations and prosecutions. MLATs are designed to facilitate cooperation

in addressing serious cases of criminal activity including cybercrime. This

international standardised process allows a court or judge to review each

request before data is accessed.[6]

2.8

MLATs present a number of challenges to law enforcement agencies; some

of these challenges are discussed in subsequent chapters.

Five Eyes Alliance

2.9

The Five Eyes Alliance is an intelligence alliance involving the United

Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. It was formally

founded on 5 March 1946

as a multilateral post-war agreement for cooperation in signals

intelligence known as the UKUSA Agreement, and subsequently expanded to include

Canada (1948) and Australia and New Zealand (1956). After more than 70 years,

its scope continues to expand in response to security concerns associated with

the emergence of new technologies.[7]

Australian law enforcement policy framework

2.10

In Australia, there has been a concerted national effort to develop a

coordinated response to cybercrime, including the implementation of a high

level policy framework to guide government, including law enforcement,

contributions to a safer and more secure online environment.[8]

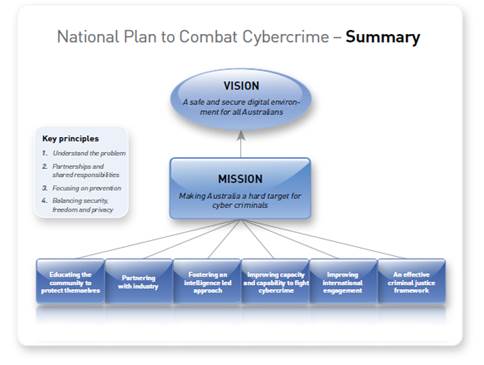

National Plan to Combat Cybercrime

2.11

In 2013 the Australian government released the first National Plan to

Combat Cybercrime.[9]

The National Plan provides a coordinated national response across

jurisdictions, based on six key principles (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Overview of National Plan

to Combat Cybercrime

2.12

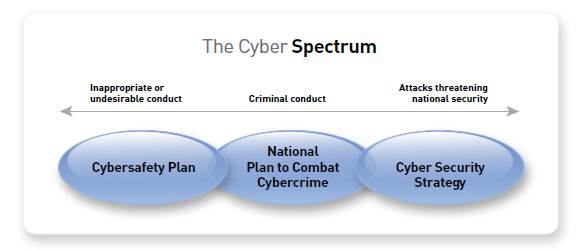

The Plan notes that cybercrimes are part of a 'cyber spectrum' of

activities ranging from broader social and personal risks associated with the

use of the internet and computers on the one hand, to attacks that threaten

national security on the other. The Plan focuses on the centre of this

spectrum: criminal conduct (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Cyber Spectrum[10]

Australia's Cyber Security Strategy

2.13

In 2016 the Prime Minister launched Australia's Cyber Security

Strategy as a 'roadmap for creating a "cyber smart nation"'. The

Strategy sets out the Australian government's philosophy and program for 'meeting

the dual challenges of the digital age—advancing and protecting our interests'

online between 2016 and 2020.[11]

2.14

It recognises that Australia needs to innovate and diversify its

economy, and embrace 'disruptive technologies' that open up new possibilities for

innovation and growth.[12]

2.15

The Strategy recognises that digital technologies bring risks, and that

strong cyber security is a 'fundamental element of our growth and prosperity in

a global economy' and vital to national security requiring partnerships between

governments, the private sector and the community:[13]

As people and systems become increasingly interconnected, the

quantity and value of information held online has increased. So have efforts to

steal and exploit that information. Cyberspace, and the dynamic opportunities

it offers, is under persistent threat.[14]

2.16

The objectives of the Strategy include:

-

the creation of jointly operated cyber threat sharing centres and

an online threat sharing portal;

-

partnering internationally to prevent cybercrime and other

malicious/nefarious cyber activity; and

-

helping to build capacity and awareness within Australia's public

and private sectors by developing a highly-skilled workforce and raising

citizens' awareness of the risks and benefits of the cyber realm.[15]

2.17

The Strategy includes a commitment to increasing the capabilities of the

Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC); a new multi-use facility for the

ACSC; additional funding for the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Australian

Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC); and engaging our regional partners to

shut down 'safe havens' for cyber criminals.[16]

It also recognises the importance of government working with the business

sector to address cyber threats.[17]

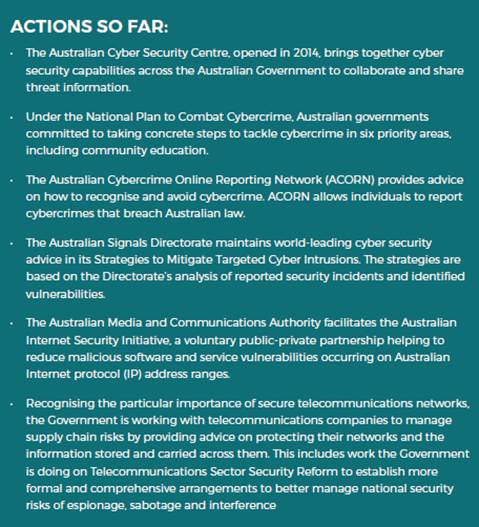

The Strategy also outlines a number of cyber security initiatives that have

been implemented in relation to building strong cyber defences (see Figure 4).

2.18

Mr Andrew Colvin, Commissioner, AFP has remarked that the Strategy

requires constant monitoring in order to keep pace with the changing cyber

security environment:

The government is constantly reviewing that strategy, and

that's because, in cybercrime, of all the crimes we deal with, two years ago is

a very long time and things have changed enormously, both in the threat actors

that we are dealing with but also in the technologies—the targets that they're

attacking.[18]

Figure 4: Australian cyber security

initiatives as at 2016[19]

A new National Plan to Combat

Cybercrime

2.19

On 19 May 2017, the Council of Australian Governments Law, Crime and

Community Safety Council, comprising ministers with responsibilities for law

and justice, police and emergency management, agreed to develop a new National

Plan to Combat Cybercrime 'to ensure a strong national approach to tackling

the increasing risks to business and individuals posed by cybercrime'.[20]

2.20

The National Cybercrime Working Group, comprising representatives from

state and territory police and justice agencies, the ACIC and the Australia New

Zealand Policing Advisory Agency, is currently overseeing the development of the

new Plan.[21]

Australia's International Cyber

Engagement Strategy[22]

2.21

In October 2017, the Australian government released Australia's

International Cyber Engagement Strategy aimed at fostering relationships

between Australia and Asia-Pacific nations, such as China, New Zealand, South

Korea and India, and improving connectivity, collaboration, and access

throughout the region, especially in areas such as cyber security and internet

governance.[23]

2.22

The Strategy has led to the formation of the Asia Pacific Computer

Emergency Response Team (APCERT), a combination of CERTs from several nations

that monitor and protect cyberspace in the region. It is also anticipated that overall

regional cyber security capability will be strengthened as a result of the

establishment of the Pacific Cyber Security Operational Network (PaCSON) to

provide operational points of contact.[24]

Australian law enforcement agencies

2.23

Within Australia, responsibility for dealing with the different forms of

cybercrime is shared between national, state and territory law enforcement and

security agencies.[25]

Department of Home Affairs

2.24

The government established the portfolio of Home Affairs in December

2017. It includes the ACIC, AFP, Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), Australian

Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC), Australian Border Force

(ABF), and Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), representing

an amalgamation of national security, emergency management and criminal justice

functions from across government.[26]

The portfolio also encompasses the Commonwealth Ombudsman which remains an

independent statutory authority.[27]

2.25

The Department of Home Affairs (DHA), Attorney-General's Department

(AGD) and Australian Border Force (ABF) stated that strong cyber security is

'fundamental to our economic growth and is vital for our national security'.

They noted that the Home Affairs portfolio established in December 2017 is

designed to be a central policy agency providing coordinated strategy and

policy leadership.

Strong oversight and accountability is important to give the

public confidence that our agencies not only safeguard our nation's security,

but do so respecting the rights and liberties of all Australians.[28]

Australian Commission for Law

Enforcement Integrity

2.26

The Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) is a

statutory authority established by the Law Enforcement Integrity

Commissioner Act 2006 (the LEIC Act).

2.27

ACLEI is the only Commonwealth agency dedicated to the prevention,

detection and investigation of corrupt conduct. It forms part of the

Australian government's anti-corruption framework, focusing on agencies

with law enforcement functions operating within a high-corruption risk

environment.[29]

Much of the information gathered by ACLEI occurs covertly—including through lawful

access to digital records, and by using electronic surveillance capabilities.

Often, ACLEI uses covertly-obtained material as a basis to collect additional

information using its other investigatory tools—such

as by issuing a summons for a person to attend a private hearing to give

evidence, or corroborating information in another way (including by issuing

notices to produce documents, or by conducting a search of premises under

warrant).[30]

2.28

ACLEI works closely with other agencies subject to the

Integrity Commissioner's jurisdiction to share information and insights to

identify vulnerabilities in the agencies' practices and procedures and help

strengthen anti-corruption policies and arrangements. It also publishes case

studies, investigation reports and articles on its website to assist corruption

prevention practitioners.[31]

Australian Criminal Intelligence

Commission

2.29

The ACIC is Australia's national criminal intelligence agency. It

commenced operations on 1 July 2016, bringing together the Australian Crime

Commission (ACC) and CrimTrac to form Australia's national criminal

intelligence agency equipped with intelligence, investigative and information

delivery functions.

2.30

The ACIC 'works with partners on the serious and organised crime threats

of most harm to Australians and the national interest'.[32]

One of the agency's key priorities is to explore the future of crime and

justice, including the emergence of new technologies and potential impacts.[33]

2.31

The ACIC is the system administrator responsible for the operation of the

Australian Cybercrime Online Reporting Network (ACORN). In 2018−19, the Australian

government allocated $59.1 million to the ACIC to develop the National Criminal

Intelligence System (NCIS) as a whole of government capability to share criminal

information and intelligence. The NCIS is discussed further in Chapter 6.

Australian Cyber Security Centre

2.32

The Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), established by the

Australian government in November 2014, brings together law enforcement and

security agencies from across the nation and leads the Australian government's

efforts to improve cyber security.

2.33

ACSC is located within the ASD. Its role is to continuously monitor

cyber threats across the globe, and provide advice and information about how

Australians can protect themselves and their businesses online.

2.34

ACSC also works with government, business and academic partners and

experts in Australia and overseas to investigate and develop solutions to cyber

security threats through a national network of Joint Cyber Security Centres.[34]

2.35

The Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT), based in the ACSC, was launched

in 2010 to provide Australian businesses, Australia's critical infrastructure

and other systems of national interest (rather than individuals or small

businesses) with advice and support in mitigating cyber threats.[35]

Australian Federal Police

2.36

The AFP plays a pivotal role in enforcing federal criminal law and

protecting the Australian national interests from crime by operating in the

evolving digital and law enforcement landscape.

2.37

The AFP Corporate Plan 2017–18 lists a key focus of the AFP's capability

development in continuously building on the ability to strengthen information

on demand as well as detect, prevent and predict serious crime through deep

data exploration. Other key focuses identified in the Corporate Plan include

the ongoing partnerships with industry to invest in innovation to combat

serious and organised crime.[36]

Australian Signals Directorate

2.38

The single biggest concentration of national cyber expertise lies within

the ASD. The Cyber Security Research Centre (CSRC) noted that the central role

and expertise of the ASD will be critical in future in ensuring an effective cooperative

national effort on cybercrime.[37]

Australian Transaction Reports and

Analysis Centre

2.39

The Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) is

Australia's financial intelligence unit and anti-money laundering and

counter-terrorism financing regulator. Its purpose is to protect the integrity

of Australia's financial system and contribute to the administration of justice

through its expertise in countering money laundering and the financing of

terrorism:

AUSTRAC works closely with law enforcement and national

security intelligence agencies, primarily on counter-terrorism and

counter-terrorism financing matters, as well as other national security

priorities. AUSTRAC's intelligence has played an important role in identifying

new suspects linked to terrorism in Australia and overseas, and has improved

Australia's understanding of high-risk funds flows to Syria, Iraq and

surrounding countries.[38]

Other agencies

2.40

Other Australian government agencies with existing cybercrime and cyber

security responsibilities also include:

-

the Australian Digital Health Agency, which is responsible for

the Australian government's digital health program, and Digital Health Cyber

Security Centre;

-

the Australian Taxation Office and Department of Social Services,

which work to ensure a more secure cyber environment for Australians;

-

the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), which is

responsible for counter-intelligence activities overseas; and

-

the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), which

is part of the Home Affairs portfolio and responsible for issues relating to

cyber espionage in Australia.[39]

2.41

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner was established in July 2015.[40]

The role of the office is to promote online safety for all Australians by

coordinating online safety efforts of government, industry and the

not-for-profit community. The office has 'a broad remit' including:

-

a complaints service for young

Australians who experience serious cyberbullying

-

identifying and removing illegal

online content

-

tackling image-based abuse.

The Office also provides audience-specific content to help

educate all Australians about online safety including young people, women,

teachers, parents, seniors and community groups.[41]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page