Bills Digest No. 20, 2022–23

PDF Version [598KB]

Ian Zhou

Economic Policy Section

28 September 2022

|

Key points

- The Financial Sector Reform Bill 2022 deals with three separate policy measures:

- the Financial Accountability Regime

- the Compensation Scheme of Last Resort

- consumer credit law reforms.

- The Financial Accountability Regime (FAR) aims to increase transparency and accountability across the financial services industry.

- The Compensation Scheme of Last Resort (CSLR) will provide compensation to victims of financial misconduct who have not been paid, typically because the financial institution involved in the misconduct has become insolvent.

- The Financial Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy Bill 2022 and the Financial Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy (Collection) Bill 2022 support the CSLR by forming the levy framework to fund the CSLR.

- Consumer credit law reforms aim to enhance consumer protections for people taking out small amount credit contracts (SACCs, also known as payday loans) and consumer leases.

- Opinions about the three policy measures are divided. While some stakeholders argue the measures will protect consumers, others say they impose unnecessary red tape on the financial services industry. In particular, attitudes toward consumer credit reforms vary widely.

- There have been several attempts by parliamentarians to reform consumer credit laws regarding SACCs and consumer leases.

- The Bills bear some resemblance to the Bills introduced by the previous Government in the 46th Parliament. The previous Bills lapsed at the dissolution of the 46th Parliament.

|

Contents

Glossary

Purpose and structure of the Bills

History of the Bills

History of SACC and consumer lease

law reforms

Committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Schedules 1 and 2 of the FSR Bill

2022 – Financial Accountability Regime

Schedule 3 of the FSR Bill 2022 –

Compensation Scheme of Last Resort

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 –

SACCs and consumer leases

Commencement date

Concluding comments

Annexure 1 – recommendations of the

2016 SACC Review

Annexure 2 – major differences

between the 2020 Bill and the FSR Bill 2022

Date introduced: 8 September 2022

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: various dates as set out in the body of this Bills Digest.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the home

pages for the Financial

Sector Reform Bill 2022, the Financial

Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy Bill 2022 and the Financial

Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy (Collection) Bill 2022, or

through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at September 2022.

Glossary

Purpose and

structure of the Bills

The Financial

Sector Reform Bill 2022 (the FSR Bill 2022) gives legislative effect to

three separate policy measures.

Schedules 1 and 2 of the FSR Bill 2022 provide

transitional arrangements for the Financial Accountability Regime (FAR).[1]

Schedule 3 of the FSR Bill 2022 establishes a financial

services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort (CSLR).[2]

The Financial

Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy Bill 2022 and the Financial

Services Compensation Scheme of Last Resort Levy (Collection) Bill 2022 support the CSLR by forming the levy framework to

fund the CSLR.[3]

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 proposes to amend the National

Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (the NCCP Act) to implement the

Government’s response to the 2016

Review of Small Amount Credit Contract Laws (SACC Review). Put

simply, Schedule 4 imposes new obligations and requirements for providers of small

amount credit contracts and consumer leases.

As each of the three measures set out in the various

Schedules to the FSR Bill 2022 are independent of each other, the relevant

background on the measures and analysis of provisions are set out under each

Schedule number.

History of the Bills

Lapsed 2021

Bills

The Morrison Government introduced the following four

Bills into the House of Representatives on 28 October 2021:

The four 2021 Bills intended to establish the FAR and the

CSLR and they were packaged together because they represented the final tranche

of legislation to implement the recommendations made by the Banking Royal

Commission.[4]

The four 2021 Bills were not debated and they lapsed at the dissolution of the

46th Parliament on 11 April 2022.

The Albanese Government introduced the following four

Bills to the House of Representatives on 8 September 2022:

In addition to the FAR and the CSLR, consumer credit

reforms regarding SACCs and consumer leases have been packaged into the FSR

Bill 2022 (discussed further below).

A separate Bills

Digest has been prepared with respect to the Financial Accountability

Regime Bill 2022. The latter three Bills (the Bills) are the focus of this

Bills Digest.

What are

the similarities and differences between the lapsed 2021 Bills and the 2022

Bills?

The Financial Accountability Regime Bill 2022 is almost

identical in content to its lapsed 2021 counterpart.

Schedules 1 and 2 of the FSR Bill 2022 (FAR-related

provisions) are also drafted in almost identical terms to the lapsed, Financial

Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response No. 3) Bill 2021, though the

FSR Bill has obviously been retitled.[5]

Schedule 3 of the FSR Bill 2022 (CSLR-related provisions),

the Levy Bill, and the Collection Bill also bear strong resemblance to the

lapsed 2021 Bills. Nevertheless, there are some minor differences between the

2022 Bills and the lapsed Bills with respect to the CSLR (discussed further

below).

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 (SACC and consumer lease

law reforms) has no counterpart in the lapsed 2021 Bills. Put simply, the

lapsed 2021 Bills did not deal with SACC or consumer lease law reforms.

Although Schedule 4 has no counterpart in the 2021 Bills,

the Schedule bears strong resemblance to Bills introduced in 2019 and 2020

(discussed below).

Why are

three separate policy measures packaged together into the FSR Bill 2022?

The Government (for example, Treasury ministers)

determines the Bill packaging process and what policy measures that go into a

Bill. It is not uncommon for a Bill to deal with several different measures.

All three policy measures (FAR, CSLR, and consumer credit

law reforms) are financial sector reform measures.

History of

SACC and consumer lease law reforms

Unsuccessful

attempts to reform consumer credit protection laws

There have been several unsuccessful attempts by some parliamentarians

to reform the laws governing SACCs and consumer leases.

Consumer advocacy groups have long held the view that the laws

governing SACCs and consumer leases should be reformed to strengthen consumer

protections. In August 2015, the Coalition Government announced an independent Review

of the Small Amount Credit Contract Laws (the SACC Review). The final

report of the SACC Review was published in March 2016.

The final report made 24 recommendations relating to the

SACC and consumer lease laws.[6]

On 28 November 2016, the Government formally responded to the report

and accepted many of the recommendations. The recommendations and the

Government’s response are set out in Annexure 1 of this Bills Digest.

In October 2017, the Government released an exposure draft

of the National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2017 (exposure draft 2017 Bill) for stakeholder

consultation.[7]

The exposure draft was designed to implement the Government’s response to the SACC

Review.[8]

However, once the consultation process was completed, the Government did not

introduce an equivalent Bill into the Parliament.

Some non-government members (for example, Rebekha Sharkie

MP and Madeleine King MP) were vocal supporters of the exposure draft 2017 Bill.[9]

They criticised the Government for its ‘failure to reform payday lending’.[10]

On four occasions between February 2018 and September

2019, Bills that replicated the provisions of the exposure draft were introduced

to the House of Representatives by non-government members.[11]

Those Bills were not debated.[12]

In December 2019, Senator Stirling Griff (of Centre Alliance)

and Senator Jenny McAllister (of ALP) co-sponsored the National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2) (the 2019 Bill) as a private Senators’ Bill.[13]

The 2019 Bill was in equivalent terms to the Government’s exposure draft that had

previously been the subject of consultation in October 2017.

The Senate referred the 2019 Bill to the Senate Economics

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report, and the Committee (chaired by

Senator Brockman) recommended the Senate not pass the Bill.[14]

ALP and Centre Alliance senators made a dissenting report and recommended the 2019

Bill be passed.[15]

The Bill lapsed at the dissolution of the 46th Parliament.

In November 2020, Andrew Wilkie MP introduced the National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2020 (the Wilkie Bill) as a private member’s Bill. The Wilkie

Bill was in similar terms to the 2019 Bill and its predecessors. The

Independent Member argued it was ‘Time to crack down on payday lending’.[16]

The Bill was not debated.[17]

In December 2020, the Coalition Government introduced the National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Supporting Economic Recovery) Bill 2020 (the 2020

Bill).[18]

Measures to repeal responsible lending laws and measures to reform the SACC

regulations were packaged together into the 2020 Bill.

Consumer advocacy groups criticised the Coalition

Government for attempting to ‘water down’ the recommendations of the SACC

Review:

Key ‘protections’ in the [2020] Bill are merely watered-down

versions of recommendations of the SACC Review, with some of these changes

directly contradicting specific findings of the report. The protections in the Bill

are not sufficient, and will continue to see people pushed into financial

hardship through expensive, predatory payday loans and consumer leases.[19]

Although the 2020 Bill was debated in and passed by the

House of Representatives then subsequently introduced in the Senate, the 2020

Bill lapsed at the end of the 46th Parliament.[20]

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 bears strong resemblances

to most of the lapsed Bills noted above. Nevertheless, there are some minor

differences between the FSR Bill 2022 and 2020 Bill and the differences are set

out Annexure 2 of this Bills Digest.

Why do

stakeholders disagree about consumer credit law reforms?

While there is consensus to protect consumers from falling

into unsustainable debt, stakeholders often disagree about consumer credit law

reforms because they disagree about how much credit/debt consumers should have

access to.

In economics, credit and debt are two sides of the same

coin. More credit in the economy goes hand in hand with more debt. The

efficient flow of credit is vital to the proper functioning of the Australian

economy as credit is necessary for many consumers to fund expenses.

The Government and the Reserve Bank seek to influence the

availability of credit in the economy through fiscal policy, monetary policy,

and regulations.

If consumer credit protection laws are too restrictive,

then consumers will not have accessible credit (for example, payday loans) to

fund emergency expenses; lenders will struggle to survive. If the laws are too

loose, then consumers get too much credit and may take on more debt than they

can sustain; lenders may target vulnerable Australians.

Because stakeholders often disagree about the

restrictiveness of Australian credit laws, they adopt different policy

positions.

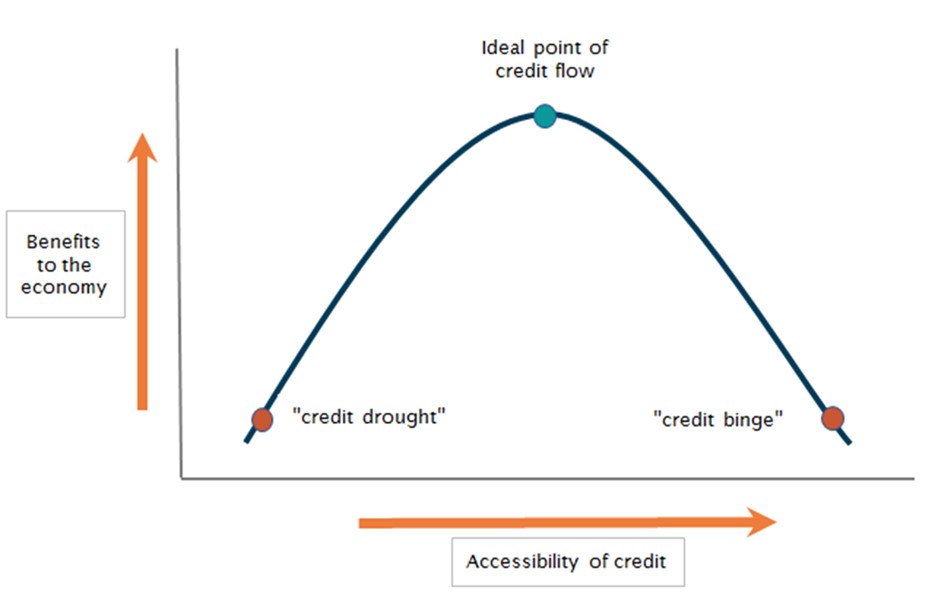

Figure 1 below shows the impact of credit on the Australian economy

from a macroeconomic perspective.

Figure 1: credit accessibility and its impact on the economy

Source: Parliamentary Library

Source: Parliamentary Library

Committee

consideration

Senate

Selection of Bills Committee

On 8 September 2022, the Senate Selection of Bills

Committee deferred consideration of the Bills to its next meeting.[21]

Senate Standing Committee

for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

has yet to consider the Bills.[22]

The Committee raised scrutiny concerns regarding the

lapsed 2020 and 2021 Bills.[23]

Senate Economics

Legislation Committee

At this stage it is not clear whether the Bills will be

referred to the SELC for inquiry and report.

The SELC conducted inquiries into the lapsed 2019, 2020

and 2021 Bills.

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Liberal Party of Australia

At the time of writing, the Liberal Party of Australia has

not commented publicly on the Bills.

Australian Greens

At the time of writing, the Australian Greens have not

commented publicly on the Bills.

Financial

implications

In relation to the FAR and consumer credit reforms, the

Explanatory Memorandum states there are no financial implications arising from

the Bills.[24]

In relation to the CSLR, the Explanatory Memorandum states

there will be some financial cost in setting up and maintaining the CSRL:[25]

| 2022-23 |

2023-24 |

2024-25 |

2025-26 |

| -$2.7m |

$0.5m |

-$0.1m |

-$1.6m |

Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bills are compatible.[26]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights has yet to consider the Bills. The Committee had no comments

with respect to the lapsed 2021 Bills.[27]

Schedules 1

and 2 of the FSR Bill 2022 – Financial Accountability Regime

Background

– what is the FAR?

The FAR is an accountability framework that imposes four

fundamental sets of obligations on the financial services industry. Senate

committees’ consideration and stakeholders’ view of the FAR are discussed in a

separate Bills Digest for the Financial

Accountability Regime Bill 2022.

What the FSR

Bill 2022 does?

Schedules 1 and 2 of the FSR Bill makes

consequential amendments to the following legislation to support the FAR and

enable transitional arrangements from the existing Banking Executive

Accountability Regime to the FAR:

Schedule 3 of

the FSR Bill 2022 – Compensation Scheme of Last Resort

What is the

CSLR?

The CSLR is a proposed scheme that will provide

compensation to eligible victims of financial misconduct who have not been

paid, typically because the financial institution involved in the misconduct

has become insolvent.

The CSLR arose from the Government’s commitment to

implement Recommendation 7.1 of the final report of the Royal

Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial

Services Industry (known

as the Banking Royal Commission or Hayne Royal Commission).

Who will be

covered by the scheme?

As the name suggests,

the CSLR will provide compensation to consumers as a last resort in specific

circumstances—when the Australian Financial Complaints

Authority (AFCA) has

made a determination in favour of the consumer who experienced financial

misconduct, and the financial institution in dispute has not paid in accordance

with the AFCA determination (typically because of insolvency).[29]

The proposed

scheme is limited in its scope:

- the

CSLR will only apply to unpaid AFCA determinations. Unpaid victims of

financial misconduct as determined by court and tribunal rulings will not be

covered by the CSLR

- the

CSLR’s maximum compensation for each AFCA determination is capped at $150,000

- the

CSLR will consider claims for unpaid AFCA determinations when the financial

complaint is made to AFCA after 1 November 2018 (the date that AFCA commenced

operations)

- according

to a policy proposal paper released by the Treasury

in July 2021, the CSLR was intended to provide compensation to unpaid consumers

who experienced financial misconduct in relation to five types of financial

products and services

- however,

under the FSR Bill 2022, the CSLR applies to unpaid determinations about one or

more of the following (proposed section 1065 of the Corporations Act 2001, at item 3 of

Schedule 3

to the FSR Bill 2022):

- engaging

in credit activity as a credit provider or other than as a credit provider

- providing

financial product advice that is personal advice provided to a person as a retail

client about at least one financial product

- dealing

in securities for a person as a retail client other than issuing

securities.credit provision

Speaking in respect of the Bills, Assistant Treasurer

Stephen Jones said:

The scope of the CSLR reflects financial products that have a

history of unpaid determinations and have been subject to significant

regulatory reform which have reduced the risk of misconduct. This is an

important point. The government will continue to consider potential enhancements

to the regulatory framework of managed investment schemes.[30]

How will

the CSLR be funded?

Annual levy

The proposed CSLR will be industry-funded.[31]

In other words, when victims of financial misconduct are unpaid due to a

financial institution’s insolvency, it is up to the rest of the financial

services industry to meet the shortfall via an annual levy to fund the CSLR.

For the scheme’s first levy period, the Australian Government

will provide funding to the CSLR operator to meet the initial estimate of

claims, fees, and costs. From the second year onwards, the CSRL will be

industry-funded.[32]

The Collection Bill will establish the power for the

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to issue levy notices

and collect levies from relevant financial firms for the purpose of funding the

scheme (clauses 13 and 16 of the Collection Bill).

The annual levy will be payable by entities that provide

financial products and services which are within the scope of the CSLR (that

is, those products and services which are authorised to be provided by

Australian financial services licence and Australian credit licence holders who

are required by legislation to be AFCA members).

The annual levy that can be raised by the CSLR is subject

to a cap of $250 million (clause 17 of the Levy Bill).[33]

According to the Treasury’s CSLR proposal paper:

The amount is considered high enough to fund claims for

compensation in circumstances where there has been a large or ‘black swan’

event relating to a financial firm providing an in-scope financial product or

service. Additionally, the amount is also considered low enough to support the

sustainability of the scheme by limiting its potential yearly impact on

leviable financial firms throughout the life of the scheme.[34]

The amount of levy that may be imposed in any particular

subsector is capped at $20 million (clause 17 of the Levy Bill). This is one of the

major changes between the lapsed 2021 Bills and the 2022 Bills. The lapsed 2021

Bills proposed that the subsector cap should be at $10 million, this has been

raised to $20 million.

The sub-sector cap is intended to provide assurance to

sub-sectors about the maximum amount expected to be levied against each

sub-sector in a levy period, absent Ministerial involvement. Practically,

raising the sub-sector cap reduces the likelihood that a sub-sector cap would

be exceeded in any given levy period and therefore reduces the likelihood of

the need for Ministerial involvement.[35]

The CSLR levy framework will

align with the ASIC industry funding model/cost recovery framework to ease the

regulatory burden on the industry.[36]

One-off

levy and special levy

In addition to the annual levy, a one-off levy will be

imposed in the 2023–24 financial year. The one-off levy will be payable by the

ten largest financial firms, excluding private health insurers and

superannuation trustees (clause 10 of the Levy Bill).

The Bills also prescribe that the Minister (the Treasurer)

can impose a special levy to respond to unexpected events or cost outlays (proposed section 1069H

of the Corporations

Act 2001, at item 3 of Schedule 3 to

the FSR Bill 2022).

Delegated

legislation

The Bills provide power to make Regulations about the

CSLR. For example, details of the levy calculations will be prescribed in the

Regulations (clause

8 of the Levy Bill). On 8 September 2022, the

Government released an Exposure Draft of the

Regulations for consultation process.

Policy

position of major interest groups

In August 2021, eight financial

industry associations issued a joint media release

to oppose the proposed CSLR, claiming that the scheme will add unnecessary red

tape and increase costs to the financial advice sector. The eight financial

industry associations said:

The draft legislation establishes a CSLR operator as a

subsidiary of AFCA. This adds unnecessary red tape by requiring the

ASIC to administer invoices and payments and significantly increases the Governments [sic] administration costs

of the financial advice sector with little benefit to consumers.

ASIC fees for financial advisers have increased by more than 230 per cent over

the past three years. Most financial advisers are sole traders or small

businesses who cannot afford the rising costs associated with increased

regulation…

Responsibility for consumer

losses and complaints should be shared evenly across the sector. However, the

proposed scheme does not apply to some industry participants, such as product

manufacturers.[37]

[emphasis added]

The belief that the CSLR will

increase costs to the financial advice sector is based on the argument that the

scheme penalises good performers to fund the mistakes of bad performers (that

is, imposing a levy on the industry to fund the mistakes of insolvent firms).

Based on publicly available information, the financial

industry associations have not changed their policy position with the

introduction of the 2022 Bills.

Consumer

advocacy groups

Broadly speaking, consumer advocacy groups support the

establishment of the CSLR.[38]

However, they recommend the Government expand the scope of CSLR. Specifically,

they believe a CSLR should:

- cover

victims of financial misconduct as determined by court and tribunal rulings

- cover more financial products and services such as managed

investment schemes

- increase the proposed individual payment compensation cap

of $150,000 because ‘this cap is too low for some people who have suffered

losses from financial advice scandals’

- have more options available in the event of a funding

shortfall and

- the Minister should have the power, by Regulations, to

increase the annual scheme cap above $250 million.[39]

Schedule 4 of

the FSR Bill 2022 – SACCs and consumer leases

What are

SACCs?

Small amount credit contracts (SACCs) are unsecured loans

of up to $2,000, where the term of the contract is between 16 days and 12

months (in other words, borrowers have between 16 days and 12 months to repay

the loan).[40]

SACCs are also known as ‘payday loans’ because they are typically advertised as

a quick-fix solution for a person to fund unexpected purchases that could arise

a few days before a payday, when the person needs cash.

Compared with traditional personal loans that consider a

borrower’s entire credit history and financial situation, SACCs are more

accessible because their approval process is quicker as they mostly focus on

the borrower’s income.[41]

Under the current consumer credit laws, there is a cap on fees

for payday loans. Licensed lenders cannot charge interest on payday loans, however

lenders can and do typically charge high fees including:

- a

maximum of 20% establishment fee calculated on the amount being borrowed

- a maximum

of a 4% monthly fee

- default

fees and enforcement costs.[42]

According to the Government, SACCs are generally used by

consumers with lower incomes or those who are unable to access cheaper

mainstream sources of credit.[43]

Opinions regarding SACCs are divided: while consumer

advocacy groups believe SACCs are ‘debt traps’ that target vulnerable

Australians,[44]

SACC lenders argue the loans facilitate financial inclusion for customers that

would otherwise be excluded from the banking sector.[45]

Policy

position of major interest groups

Consumer

advocacy groups

Consumer advocacy groups have persistently argued that the

laws governing SACCs and consumer leases should be strengthened. In August

2019, they formed the Stop the Debt

Trap Alliance to campaign for consumer credit law reforms.

Consumer advocacy groups have welcomed the introduction of

the FSR Bill 2022. They argue the Bill will enhance ‘long overdue consumer

protections for high-cost payday loans and consumer leases’.

For example, the CEO of Financial Counselling Australia

said:

Financial counsellors are delighted that this long-awaited

legislation has finally been introduced to the Parliament. Every day we see

clients with high-cost payday loans and consumer leases that they struggle to

pay.

The most important part of this [FSR] Bill will be in the

accompanying regulations that will cap the amount a person can pay for each

product to 10% of income. This will make it less likely that people will end up

trapped in a never-ending cycle of debt.[46]

SACC

lenders

SACC lenders have not publicly commented on the FSR Bill

2022. Judging from their previous comments on the lapsed Bills, they tend to

adopt a more nuanced position regarding consumer credit law reforms.

While they supported most provisions in the 2019 Bill,

they criticised some specific provisions for being overly restrictive. Criticisms

of specific provisions are discussed below in the ‘Key issues and provisions’

section.

In its submission to the 2019 Bill, the National Credit

Providers Association (NCPA, a peak body representing SACC lenders) said:

The consumer activists ‘stop the debt trap’ campaign is

misleading and uses false statements to misrepresent legitimate and highly

regulated Australian businesses…

The NCPA has worked with governments since the introduction

of the NCCP Act 2009 to ensure responsible lending obligations are the

basis for consumer protections and have long called on the government to do

more in areas where some credit operators provide less regulated products.[47]

Cash Converters, one of Australia’s largest SACC lenders,

said:

Cash Converters will continue to support sensible legislation

that provides meaningful protection for its customers, but it will not support

legislation that has arbitrary cap (10% PEA) applied that… can create financial

exclusion and impinges on personal choices of employed Australians.[48]

Key issues

and provisions regarding SACC reforms

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 implements the

Government’s response to the recommendations of the SACC review by:

- providing

a new regulation-making power that can be used to ensure that all consumers are

covered by a protected earnings amount, for example by reducing the existing loan

repayment cap from 20% of a person’s gross income to 10% of a person’s net

income (item 12 of Schedule 4)

- requiring

SACC providers to have equal repayments and equal repayment intervals over the

life of the loan to prevent providers from artificially extending the life of a

loan (item 14, proposed section 133CD of the NCCP Act)

- prohibiting

SACC providers from charging monthly fees in respect to any residual term of

the loan where a consumer repays the loan early (item 15, proposed section

31C of the National Credit Code)

- prohibiting

unsolicited offers to prompt certain consumers to apply for a SACC (item 14,

proposed section 133CF)

- introducing

a new prohibition on SACCs providers making referrals under certain

circumstances (items 57–59 in Part 3 of Schedule 4)

- requiring

SACC providers to give information to consumers about SACCs in accordance with

ASIC requirements (item 14, proposed section 133CE).

Key issue 1

– Extending ‘Protected Earnings Amount’ protection to all consumers and

reducing repayment cap from 20% to 10%

The FSR Bill 2022 introduces a new regulation-making power

that can be used to ensure that all consumers are covered by a protected

earnings amount.

PEA is the amount of a consumer’s income that can be used

for payday loan repayments. Currently, PEA protection only applies to a class

of consumers who receive at least 50% of their gross income from social security

payments.[49]

These consumers are perceived as more vulnerable and therefore the payday loan

repayment cap for these consumers is set at 20% of the consumer’s gross income.[50]

In other words, SACC licensed lenders are prohibited from entering into a SACC with

these vulnerable consumers that would require them to commit more than 20% of

their gross income into repaying the loan.

Part 1 of Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 amends the

NCCP Act to enable the Government (through the National Consumer

Credit Protection Regulations 2010) to set a PEA on SACC repayments for all

consumers, not just these vulnerable consumers who receive at least 50% of

their gross income from social security payments.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

It is expected that the regulations will provide a protected

earnings amount of 10 per cent of a person’s net income for all consumers,

meaning that a licensee cannot enter into a contract if the total repayments

would exceed 10 per cent of the consumer’s net income.[51]

Stakeholders’ commentary regarding reducing repayment cap from 20% to 10%

The National Credit Providers

Association (NCPA) made a submission in respect of the lapsed 2019 Bill and

criticised the potential reduction in repayment cap as regulatory

over-reach:

Ordinary Australians who are

unable to access credit from a mainstream lender such as a bank should be

free to choose the best credit option available, rather than be told they

can only access 10% of their net income for repayments. The latest CoreData research on small loans indicates

that 64.4% of customers are working Australians. Lowering the PEA to 10%

will have significant consequences for the 3 million Australians who are

unable to or choose not to access credit through main-stream financing.

The NCPA and Cash Converters are

not aware of another financial services sector that are subject to such

extreme over-reach where the government effectively controls how employed

consumers can spend their own money. The effects of lowering the PEA to 10%

of net income for all Australians also renders responsible lending

obligations null and void because they are not required under such a

prescriptive legislative model…

The NCPA proposes no change

to Section 133CC of the NCCP Act

2009 as the protected earnings amount

is working as intended following the reforms of 2013. [emphasis added][52]

|

Put simply, if passed the FSR

Bill 2022 and associated changes to regulations will extend PEA protection to

all consumers. Furthermore, the FSR Bill 2022 will enable regulations to reduce

the existing loan repayment cap from 20% of a consumer/borrower’s gross income

to 10% of the person’s net income (after tax and other deductions).[53]

Stakeholders’

commentary regarding reducing repayment cap from 20% to 10% (continued)

In contrast to the policy

position taken by the NCPA, the Consumer Action Law Centre (a consumer

advocacy group) suggested that the repayment cap should be lower than 10%:

… the 10% protected earnings

amount for consumer leases and payday loans are critical reforms that would

provide much needed protections for borrowers. We have strongly opposed more

lenient caps, which would fail to address the harm caused by these products…

Research by the Pew Trust in the

United States found that in order to fit the budgets of typical payday loan

borrowers, payments should not exceed 5% of monthly income, making the 10%

cap proposed by the SACC Review a very generous compromise.[54]

|

Key issue 2 – Requirements

for equal repayments over the life of a loan

The SACC Review identified that some SACC providers were

engaging in a practice of ‘front loading’ a consumer’s repayments. ‘Front

loading’ means extending the life of a loan to generate extra revenue for the

provider from monthly fees charged to the consumer.

To address this problem, item 14 in Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 inserts proposed section 133CD into Part 3-2C of the NCCP Act. The proposed section 133CD provides that a SACC must have equal repayments over the life of the loan.

Explainer: what is ‘front loading’ and why is it a problem for

borrowers?

From a borrower’s

perspective, paying off a loan as fast as possible is usually in his or her

best financial interest because the longer a loan is, the more fees it

accumulates.

On the other hand, SACC

lenders typically want their loans to last longer to maximise fees. However,

lenders must also consider that a longer loan potentially carries a higher

default risk because unforeseen circumstances can happen to the borrower.

To give a hypothetical

example, Peter has signed a 12-month loan with a SACC lender in January

2022. While the lender gets to charge 12 months’ worth of fees on Peter from

January to December 2022, the lender is also concerned that Peter may suffer

an accident in July and be unable to repay the remainder of his loan.

To get the best of both

worlds, the SACC lender can stipulate that Peter must repay the bulk of his

loan from January to June 2022, and then make smaller repayment amounts from

July to December. This way the lender still gets to charge 12 months’ worth

of fees, but if some accident does befall Peter in July, the lender would

still have recovered most of the loan amount.

The practice of making Peter

repay the bulk of a loan early on is called ‘front loading’. This practice

can be banned if legislation requires that payday loans must have equal

repayment amounts over equal intervals. In other words, the laws can require

SACC lenders to ensure Peter pays the same monthly repayment amount from

January to December 2022.

Note that most SACC lenders

supported the requirement for equal repayments and repayment intervals when

the lapsed 2019 Bill proposed this measure.

|

To address this problem, item 14 in Schedule 4 of

the FSR Bill 2022 inserts proposed section 133CD into Part 3-2C of the NCCP

Act. The proposed section 133CD provides that a SACC must have equal

repayments over the life of the loan.

Key issue 3 – Ban on unsolicited

SACC communications

Item 14 in Schedule 4 inserts proposed section

133CF to the NCCP Act 2009. The proposed section prohibits SACC providers

from making unsolicited invitations to people who:

- have

a current payday loan with the provider or another credit provider, or

- have

at any time applied (whether successfully or unsuccessfully) for a payday loan

with the provider or another credit provider, and the provider ought to be

aware of this.[55]

An unsolicited communication to a consumer occurs when:

- the

consumer has made no prior request to the SACC provider for that communication

- the

consumer has made a prior request to the SACC provider, but that prior request

was solicited by the provider

- circumstances

prescribed by the Regulations.[56]

The ban on unsolicited SACC communications would not apply

to the general advertising of SACCs that are directed towards consumers at

large.[57]

Stakeholders’

commentary regarding the proposed ban on unsolicited SACC communications

In its submission in relation

to the lapsed 2019 Bill, Cash Stop Financial Services (a SACC lender) said

the provisions regarding a ban on unsolicited SACC communications are overly

restrictive:

This is the most restrictive

type of legislation ever proposed in a democratic country were [sic] freedom

of expression and speech are seen as an icon of our Australian system of

democracy.

It appears the legislation was

penned with the prohibitions related to unsolicited Credit Card limit

increases and or a pre-approved Credit Cards in mind.

This is totally misguided, and

unnecessary, as every Small Amount Credit Contract loan must progress

through a vigorous assessment process to ensure it is not an unsuitable

loan, where as a Credit Card limit increase or a Line of Credit product are

not, these products allow for redraws without assessment unlike a Small Amount

Credit Contract loan.[58]

Note that the ban proposed by

the 2019 Bill is more restrictive than its counterpart in the FSR Bill 2022.

For example, the 2019 Bill proposed to ban SACC lenders from making

unsolicited invitations to people who have had a payday loan with lenders in

the past two years.[59]

This specific provision does not appear in the FSR Bill 2022.

SACC lenders have not made comment

publicly about the (less restrictive) ban proposed by the FSR Bill 2022.

|

Key issue 4 – Ban on monthly fees for repaid loans

Item 15 in Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 inserts

proposed section 31C into the National Credit Code to prohibit a licensee

from requiring or accepting payment of an unexpired monthly fee from a debtor

under a small amount credit contract.

Put simply, item 15 specifies that SACC providers

will be prohibited from charging monthly fees if a consumer/borrower pays off

the loan early. Currently, SACC providers are not restricted in structuring the

loan contracts in a way that consumers are required to pay monthly fees for the

full contract term, even if the loan is discharged early.

What are consumer leases?

A consumer lease is a contract where a person rents an

item (for example a fridge, TV, sofa or iPad) from a rental company for a set period

of time.[60]

Under a consumer lease, a person must make regular payments to have use of the

item. In most instances, a person must continue to make payments even when the

item has been broken or needs replacing.[61]

The Australian Government’s MoneySmart

webpage warns that although consumer leases generally have low weekly or

fortnightly payments, over time these costs add up. A consumer could end up

paying more than double what it would cost to buy the item outright in a store.[62]

Consumer leases are regulated under Part 11 of the

National Credit Code.

Key issues

and provisions regarding consumer lease reforms

Part 2 in Schedule 4 proposes key changes to

consumer lease laws and these changes include:

- capping

the costs of consumer leases

- establishing

a method to ensure consumers are only charged early termination fees that

reflects the appropriate and reasonable loss of the lessor in the event of an

early termination of a lease

- introducing

the concept of ‘consumer leases for household goods’.

Additionally, for both SACCs and consumer leases, the

reforms improve the information that must be obtained and used in affordability

checks, enhance disclosure and warnings requirements and strengthen

recordkeeping obligations.

Key issue 1

– capping the costs of consumer leases

Item 50 in Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 inserts proposed

sections 175AA–175AC into the National Credit Code. In particular, proposed

section 175AA imposes a cap on fees and charges for consumer leases.

The permitted cap for a consumer lease is the total

of the following amounts:

- the

base price of the goods hired under the consumer lease

- the

permitted delivery fee (if any) for the consumer lease

- the

permitted installation fees (if any) for the consumer lease

- the

amount worked out by multiplying the sum of those amounts by,

- in

the case of a consumer lease for a fixed term—0.04 for each whole month of the

consumer lease to a maximum of 48 months or

- in

the case of a consumer lease for an indefinite period—1.92.[63]

The Explanatory Memorandum to the FSR Bill 2022 provides several

examples of how to calculate the maximum amount that a consumer can be charged

on a consumer lease.[64]

Key issue 2

– definition of ‘consumer lease for household goods’

Item 20 in Schedule 4 inserts new definitions into

both the NCCP Act and the National Credit Code. Put simply, Part 2 of

Schedule 4 of the FSR Bill 2022 proposes to introduce the concept of ‘consumer

leases for household goods’ to which the following applies:

- limiting

the portion of a consumer’s net income that can be committed to payments on

consumer leases of household goods, broadly consistent with the approach being

adopted for SACCs

- requiring

lessors to disclose the base price of goods hired under the lease and the

difference in total amount payable under the lease and the base price of the

leased goods

- prohibiting

door-to-door selling of consumer leases for household goods and the unsolicited

selling of these leases outside their standard business premises

- requiring

lessors to document in writing their assessment that a consumer lease for

household goods is not unsuitable.[65]

Other provisions

For both SACCs and consumer leases, the reforms aim to

improve the information that must be obtained and used in affordability checks,

enhance disclosure and warning requirements and strengthen recordkeeping

obligations.

The Bill also introduces general anti-avoidance measures that

will prohibit schemes designed to avoid SACCs and consumer leases law restrictions,

and product intervention orders under the NCCP Act.[66]

Additionally, there are enhanced civil penalties for breaches of these reforms.

Indefinite term leases will also be brought within the scope of credit

regulation.[67]

Commencement

date

Part 1 of Schedule 1 and Schedule 2 to the FSR Bill 2022

commence at the same time as the Financial Accountability Regime Bill 2022.

Part 2 of Schedule 1 to the FSR Bill 2022 commences on the date the Regime

begins to apply to the banking industry, six months after the commencement of

the Financial Accountability Regime Bill 2022.[68]

The establishment of the CSLR and the supporting levy framework

commences on the day after Royal Assent.[69]

The Collection Bill 2022 commences at the same time as the Levy Bill to ensure

that all aspects of the levy framework start on the same day. If the Levy Bill

does not commence, the Collection Bill 2022 does not commence.[70]

Provisions relating to consumer credit reforms commence on

various dates outlined in the Explanatory Memorandum.[71]

Concluding comments

The Bills package together three separate policy measures

(the FAR, the CSLR, and consumer credit law reforms).

While all three measures have been broadly welcomed by

consumer advocacy groups, the measures have also attracted some criticisms from

industry stakeholders.

Consumer credit law reforms have been a particularly

divisive issue judging by previous attempts to introduce the changes. The

Government is seeking a balance between providing adequate consumer protection

and ensuring that consumer credit laws do not become too restrictive and strangle

the flow of credit.

Annexure 1 – recommendations of the 2016 SACC

Review

The recommendations from the Review

of Small Amount Credit Contract Laws and the relevant Government response

are set out below.[72]

| Recommendation |

Government response |

Recommendation 1—affordability

Extend the protected earning amount regulation to

cover SACCs provided to all consumers. Reduce the cap on the total amount of all SACC

repayments from 20 per cent of the consumer’s gross income to 10 percent of

the consumer’s net income. Subject to these changes being accepted, retain the

existing 20 per cent establishment fee and four per cent monthly fee

maximums.

Recommendation 2—suitability

Remove the rebuttable presumption that a loan is

presumed to be unsuitable if either the consumer is in default under another

SACC, or in the 90 day period before the assessment, the consumer has had two

or more other SACCS. This recommendation is made on the condition that it

is implemented together with Recommendation 1. |

The Government accepts these recommendations in

full.

The Government supports the panel’s direction to

promote financial inclusion by ensuring that consumers do not enter into

unaffordable SACCs whose repayment absorbs too large a proportion of their

net income. The Government notes that these recommendations

directly target the harm associated with repeat borrowing, rather than repeat

borrowing per se, by reducing the likelihood of a debt spiral occurring,

while still enabling consumers to access further SACCs if the repayments are

affordable. The Government notes that it is unusual to have such

prescriptive requirements regarding the amount that a consumer can devote to

a particular form of finance; however, the panel’s report highlighted the vulnerable

customer base of SACCs. The panel noted that the principles based responsible

lending obligations appear insufficient alone to prevent observed harm; a

more strict affordability test is warranted. The Government accepts this

proposal. To assist SACC providers in complying with this

obligation, the Government will provide a safe harbour allowing providers to

rely on a consumer’s bank statements when determining a consumer’s average

income for the purposes of the protected earnings amount, unless there is

evidence suggesting that it is inappropriate to do so. The Government supports removing the current

rebuttable presumption that a SACC is considered unsuitable if a consumer has

had two or more SACCs in 90 days.

|

Recommendation 3—short term credit contracts

Maintain the existing ban on credit contracts with

terms less than 15 days.

|

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

Currently there is an outright ban on a provider

offering a credit contract which has a term of 15 days or less irrespective

of whether the credit contract is secured. The Government supports the

panel’s recommendation to maintain this ban. Loans of less than 15 days consume a disproportionate

amount of a consumer’s income due to large repayment amounts in a short period

of time. These loans are more likely to trap consumers in a debt spiral than

loans with longer durations. |

Recommendation 4—direct debit fees

Direct debit fees should be incorporated in the

existing SACC fee. |

The Government notes this recommendation.

This recommendation is the responsibility of ASIC, as

the independent regulator. In response to the recommendation, ASIC announced

on 4 November 2016 that it would remove ASIC Class Order [CO

13/818] Certain small amount credit contracts. The class order

allowed SACC providers to charge a separate fee for direct debit processing. The removal ensures that consumers are not charged

direct debit fees when taking out a SACC. The change will apply to any SACC

provided from 1 February 2017. Loans that commence before 1 February 2017

will continue to operate under the existing rules and third-party direct

debits will be able to be charged on those loans. |

Recommendation 5—equal repayments and sanction

In order to meet the definition of a SACC, the credit

contract must have equal repayments over the life of the loan. Where a contract does not meet this requirement the

credit provider cannot charge more than an annual percent rate (APR) of 48

per cent. |

The Government partially accepts this recommendation.

The Government supports the panel’s recommendation

that SACCs should have equal repayments over the life of the loan as it will

stop SACC providers artificially extending the term of the loan. ASIC will have the power to allow limited exceptions

where appropriate. However, the Government does not support the panel’s

recommendation that, where a contract does not meet the equal repayment

requirement, a credit provider cannot charge more than an annual percentage

rate (APR) of 48 per cent. This would effectively create a specific penalty

regime for this requirement, and the Government would prefer a consistent

approach to penalties across the SACC regime. |

Recommendation 6—SACC database

A national database of SACCs should not be

introduced. Rather, the major banks should be encouraged to participate in

the comprehensive credit reporting regime at the earliest date. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

This does not preclude the industry from developing

its own database. |

Recommendation 7—early repayment

No four per cent monthly fee can be charged for a

month after the SACC is discharged by its early repayment. If a consumer

repays a SACC early, the credit provider cannot charge the monthly fee in

respect of any outstanding months of the original term of the SACC after the

consumer has repaid the outstanding balance and those amounts should be

deducted from the outstanding balance at the time it is paid. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

This will allow consumers, if their loan is

discharged early, to only pay fees for the new shorter length of the loan. |

Recommendation 8—unsolicited offers

SACC providers should be prevented from making

unsolicited SACC offers to current or previous consumers. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government agrees with the principle that

consumers should only apply for a SACC when they pro-actively choose to do

so, rather than being prompted by a SACC provider. |

Recommendation 9—referrals to other SACC providers

SACC providers should not receive a payment or any

other benefit for a referral made to another SACC provider. |

The Government does not accept this recommendation.

The panel considered that it would be inappropriate

for SACC providers to refer a customer to another SACC provider after

determining that the customer is unsuitable to receive a SACC. During the

consultations undertaken following receipt of the final report, it became

apparent that there are legitimate instances where it may be appropriate for

a referral to occur. For example, some SACC providers only target specific

geographical locations. If such a SACC provider receives an application from

a consumer from another location, they may wish to refer that consumer to

another SACC provider. In addition, paying for referrals may be less

expensive than other means of attracting customers, who are in any case

subject to a cap on costs (a 20 per cent establishment fee and a 4 per cent

monthly fee). |

Recommendation 10—default fees

SACC providers should only be permitted to charge a

default fee that represents their actual costs arising from a consumer

defaulting on a SACC up to a maximum of $10 per week. The existing limitation of the amount recoverable in

the event of default to twice the adjusted credit amount should be retained. |

The Government does not accept this recommendation.

The Government will maintain the existing default cap

of twice the adjusted credit amount. Evidence provided by the SACC industry suggests that

the $10 per week default fee does not cover the costs of managing a

defaulting borrower. The Government considers the existing cap provides

sufficient restrictions to prevent SACC providers from over-charging a

consumer. |

Recommendation 11—cap on cost to consumers

A cap on the total amount of the payments to be made

under the consumer lease of household goods should be introduced. The cap

should be a multiple of the base price of the goods, determined by adding

four per cent of the base price for each whole month of the lease term to the

amount of the base price. For a lease with a term of greater than 48 months,

the term should be deemed to be 48 months for the purposes of the calculation

of the cap. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports this recommendation. The SACC

review identified the high cost of consumer leases, particularly to

vulnerable consumers. This will provide, for example, a cap of 1.48 times

of the Base Price of the goods for a 12 month lease and a multiple of 1.96

times the Base Price of the goods for a two year lease. Leases of four years

or more would be subject to a cap of 2.92 times the Base Price of the goods. For example, a two year lease for a TV valued at $500

would be limited to total payments of $980. This recommendation will make the regulation of

consumer leases more consistent with that of credit contracts, which are

subject to a 48 per cent APR cap. However, in recognition of the different

costs facing consumer lease providers, the Government supports a higher cap

on costs for consumer leases. |

Recommendation 12—base price of goods

The base price of new goods should be the recommended

retail price, or the price agreed in store, where this price is below the recommended

retail price. Further work should be done to define the Base Price

for second hand goods. |

The Government accepts this recommendation with an

amendment.

The Government supports this recommendation for new

goods. To provide a clear understandable process for

applying the cap to second hand goods, second hand goods will be subject to

the same cap as new goods, with a 10 per cent discount to the original Base

Price per annum, up to a maximum of 30 per cent. For example, a $500 TV re-leased after two years

would have a new base price of $400 for the purposes of calculating the cap. |

Recommendation 13—add-on services and features

The cost (if any) of add-on services and features,

apart from delivery, should be included in the cap. A separate one-off delivery

fee (limited to the reasonable costs of delivery of the leased goods) should

be permitted. That fee should be limited to the reasonable costs of delivery

of the leased good which appropriately account for any cost savings if there

is a bulk delivery of goods to an area. |

The Government accepts this recommendation with an

amendment.

The Government accepts that certain leased goods may

necessarily have significant installation costs, and is therefore allowing

installation of some items to be excluded from the cap. The Government will provide ASIC with the ability to

exempt the installation costs of certain leased goods from inclusion in the

cap on costs where ASIC considers it appropriate to do so. |

Recommendation 14—consumer leases to which the cap applies

The cap should apply to all leases of household goods

including electronic goods. Further consultations should take place on

whether the cap should apply to consumer leases of motor vehicles. |

The Government accepts this recommendation with an

amendment.

Following further consultation after the release of

the final report, the Government will apply the cap on costs to all consumer

leases. The Government notes that novated leases and small

business leases are not covered by the Consumer Credit Act, and will

not be affected by any changes. |

Recommendation 15—affordability

A protected earnings amount requirement be introduced

for leases of household goods, whereby lessors cannot require consumers to

pay more than 10 per cent of their net income in rental payments under

consumer leases of household goods, so that the total amount of all rental

payments (including under the proposed lease ) cannot exceed 10 per cent of

their net income in each payment period. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government notes that it is unusual to have such

prescriptive requirements regarding the amount that a consumer can devote to

a particular form of finance; however, the panel’s report highlighted the

vulnerable customer base of consumer leases. The panel noted that the principles based responsible

lending obligations appear insufficient alone to prevent observed harm; a

more strict affordability test is warranted. The Government accepts this

proposal. Capping the amount of income that can be devoted to

lease payments will ensure that consumers do not get locked into long term

lease contracts they cannot afford, while still enabling consumers to lease a

wide range of goods. To assist lessors in complying with this obligation,

the Government will provide a safe harbour allowing lessors to rely on a

consumer’s bank statements when determining a consumer’s average income for

the purposes of the protected earnings amount, unless there is evidence

suggesting that it is inappropriate to do so. |

Recommendation 16—Centrepay implementation

The Department of Human Services consider making the

caps in recommendations 11 and 15 mandatory as soon as practicable for

lessors who utilise or seek to utilise the Centrepay system. |

The Government supports this recommendation

in-principle.

The Government supports this recommendation

in-principle. Action in response to the recommendation will take account of

the outcome of litigation between The Aboriginal Community Benefit Fund Pty

Ltd and the Chief Executive Centrelink. |

Recommendation 17—early termination fees

The maximum amount that a lessor can charge on

termination of a consumer lease should be imposed by way of a formula or

principles that provide an appropriate and reasonable estimate of the

lessors’ losses from early repayment. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports this recommendation

in-principle and will undertake further consultation to finalise the formula

or principles. |

Recommendation 18—ban on the unsolicited marketing of

consumer leases

There should be a prohibition on the unsolicited

selling of consumer leases of household goods, addressing current unfair

practices used to market these goods. |

The Government partially accepts this recommendation.

The Government will prohibit door to door selling of

consumer leases. The final report highlights the concerns that sales

through unsolicited approaches are unfair and have the capacity to cause

financial harm irrespective of the target market. However, difficulties with

distinguishing between unsolicited selling and marketing mean that the

Government will only prohibit door to door sales. |

Recommendation 19—bank statements

Retain the obligation for SACC providers to obtain

and consider 90 days of bank statements before providing a SACC and introduce

an equivalent obligation for lessors of household goods. Introduce a prohibition on using information obtained

from bank statements for purposes other than compliance with responsible

lending obligations. ASIC should continue its discussions with software

providers, banking institutions and SACC providers with a view to ensuring

that ePayment Code protections are retained where consumers provide their

bank account log-in details in order for a SACC provider to comply with their

obligation to obtain 90 days of bank statements, for responsible lending

purposes. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports retaining the requirement for

SACC providers to collect 90 days of bank statements before providing a SACC

as well as introducing a requirement that lessors must also collect 90 days

of bank statements. Evidence from the final report shows that lessors are

not making sufficient inquiries when providing a lease and may be in a

position to make a more accurate assessment of consumers’ circumstances if

they collected at least 90 days of bank statements, in addition to their

responsible lending obligations. The Government also supports introducing a

prohibition on using information obtained from bank statements for purposes

other than compliance with responsible lending obligations. |

Recommendation 20—documenting suitability assessments

Introduce a requirement that SACC providers and

lessors under a consumer lease are required at the time the assessment is

made to document in writing their assessment that a proposed contract or

lease is suitable. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

This recommendation strengthens the responsible

lending obligations |

Recommendation 21—warning statements

Introduce a requirement for lessors under consumer

leases of household goods to provide consumers with a warning statement,

designed to assist consumers to make better decisions as to whether to enter

into a consumer lease, including by informing consumers of the availability

of alternatives to these leases. In relation to both the proposed warning statement

for consumer leases of household goods and the current warning statement in

respect of SACCs, provide ASIC with the power to modify the requirements for

the statement (including the content and when the warning statement has to be

provided) to maximise the impact on consumers. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports lessors being required to

provide consumers with a warning statement to assist consumers in making more

informed decisions. The Government considers that giving ASIC the

flexibility to modify the requirements for the statement will likely result

in a more effective warning over time. |

Recommendation 22—disclosure

Introduce a requirement that SACC providers and

lessors under a consumer lease of household goods be required to disclose the

cost of their products as an APR. Introduce a requirement that lessors under

a consumer lease of household goods be required to disclose the Base Price of

the goods being leased, and the difference between the Base Price and the

total payments under the lease. |

The Government partially accepts this

recommendation.

The Government supports disclosing the base price of a

lease and the difference between the base price and the total cost of a

consumer lease. The Government does not consider it appropriate to

require disclosure of an APR for consumer leases as in order to calculate an

APR it is necessary to treat the lease as a sale by instalment and assume

that the consumer owns the good at the end of the lease. This is not the

case. In addition, the Government does not consider it

appropriate to require disclosure of an APR for SACCs. While the APR does

accurately reflect their high cost nature, this is partly a reflection of the

short term nature of SACCs. |

Recommendation 23—penalties

Encourage a rigorous approach to strict compliance by

extending the application of the existing civil penalty regime in Part 6 of

the National Credit Code to consumer leases of household goods and to SACCs,

and, in relation to contraventions of certain specific obligations by SACC

providers and lessors, provide for automatic loss of the right to their

charges under the contract. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports this recommendation as it

will encourage SACC providers and lessors to comply with the Consumer

Credit Act. |

Recommendation 24—avoidance

The Government should amend the Consumer Credit Act

to regulate indefinite term leases, address avoidance through entities using

business models that are not regulated by the Consumer Credit Act, and

address conduct by licensees adopting practices to avoid the restriction on

the maximum amount that can be changed under a consumer lease of household

goods or a SACC, or any of the conduct obligations that only apply to a

consumer lease of household goods or a SACC. |

The Government accepts this recommendation in full.

The Government supports regulating indefinite term

leases. As these products are currently exempted from the consumer

protections in the Consumer Credit Act, providers are not required to

hold an Australian Credit Licence or meet responsible lending obligations.

This has resulted in opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and has been

relied upon by fringe providers of short-term and indefinite leases to avoid

regulation, including where the consumer may be disadvantaged by the use of

an unregulated lease relative to a consumer lease. The introduction of an anti-avoidance provision will

assist in avoiding a drift to non-compliance where providers who are

complying with the Consumer Credit Act are losing business to those

who are not complying and are, therefore, under financial pressure to lower

their own standards. It will also minimise consumer detriment resulting from

businesses which are avoiding compliance with cost caps and additional

responsible lending and conduct requirements. |

Source: The Treasury, Review

of the Small Amount Credit Contract Laws, final report, Treasury,

Canberra, March 2016.

Kelly O’Dwyer (former Minister for Revenue and Financial

Services), ‘Government

response to the final report of the review of the small amount credit contract

laws’, media release, 28

November 2016.

Annexure 2

– major differences between the 2020 Bill and the FSR Bill 2022

With respect to consumer credit law reforms, the major differences

between the 2020 Bill

and the FSR Bill 2022 are set out below.[73]

| National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Stronger Economic Recovery Bill) 2020

(the 2020 Bill) |

Financial

Sector Reform Bill 2022

(the 2022 Bill) |

| SACCs |

| The 2020 Bill (via

regulations) set higher thresholds than recommended by the 2016

SACC Review for protected earnings amounts (the amount of net income a

consumer can spend on a SACC or a consumer lease). It set different thresholds

for those mainly on social security (10 per cent) or not (20 per cent), and

provided consumer leases more generous thresholds than SACCs. The Review

recommended that there be a 10% threshold for each of SACCs and consumer

leases, with no differentiation between borrower on social security or not. |

The 2022 Bill introduces a new

regulation-making power that can be used to set a PEA cap of 10% (of net

income) for SACC borrowers and consumer lessees. Note that the 2022 Bill does

not contain provisions setting the 10% PEA cap. The Bill merely provides the

legislative authority (via regulations) to set the PEA cap. |

| SACCs providers would be

prohibited from making unsolicited communications with current or former

consumers. |

The 2022 Bill extends the

prohibition to include other consumers under specified circumstances (for

example, those who have unsuccessfully applied for a SACC and whose details

are still held by the SACC provider). |

| No prohibitions on referrals. |

The 2022 Bill provides that

referrals can only be made by regulated consumer credit providers to other

regulated credit providers. Referrals to unregulated credit providers are

prohibited. |

| Consumer Leases |

| The 2020 Bill allowed for the

charging of establishment fees and includes installation and delivery fees in

the base amount used to calculate the four per cent monthly fee cap on

consumer leases. Delivery and installation fees

would be allowed to be charged separately.

|

The 2022 Bill does not include

delivery or installation fees as part of the base amount for calculating the

permitted monthly fee cap for a consumer lease. Delivery and installation fees

are still allowed to be charged separately. The 2022 Bill does not allow

for the separate charging of establishment fees. |

| The 2020 Bill banned the

door-to-door selling of consumer leases. |

The 2022 Bill extends the ban

on door-to-door sales to include unsolicited contact situations where first

contact is made with a person in a non-standard business premises (for example, a

market stall, park, or other public space). |

| Combined |

| The 2020 Bill required lessors

to obtain 90 days of bank statements for use in their responsible lending assessments. |

The 2022 Bill allows the

regulations to extend the requirement to include Centrelink documents. The Bill also allows for

lenders to comply with the requirements to obtain these banking and other

documents in a technologically neutral manner. |

There was a requirement for a

court order or finding of guilt by a court, to determine if breaches of

certain of the laws would result in a credit provider losing their

entitlement to the fees and charges under the credit contract.

|

The 2022 Bill removes the

requirement for a court order or finding of guilt by a court for the loss of

charges provisions to apply. It also extends the loss of charges provisions

to unsolicited selling prohibitions specified in the Bill. |

| Anti-avoidance provisions

apply in situations where a scheme or contract was more complex or costly to

the consumer than the alternative for avoidance purposes. |

The 2022 Bill extends the

anti-avoidance provisions to include schemes created to avoid a product

intervention order made under Part 6-7A of the National Consumer Credit

Protection Act 2009. |

[1]. Stephen

Jones, Second

Reading Speech: Financial Sector Reform Bill 2022, House of

Representatives, Debates, (proof), 8 September 2022, 6.

Detailed information regarding the FAR is

provided in the Financial

Accountability Regime Bill 2022.

[2]. Stephen

Jones, Second

reading speech: Financial Sector Reform Bill 2022, 7.

[3]. Stephen

Jones, Second

reading speech: Financial Sector Reform Bill 2022, 7.

[4]. J

Frydenberg (Treasurer) and J Hume (Minister for Superannuation, Financial

Services and the Digital Economy), ‘Government

meets legislative commitments in response to Hayne Royal Commission’,

media release, 28 October 2021.

[5]. Kate Hilder and Siobhan Doherty, ‘Financial

Accountability Regime: Bills (re)introduced’, MinterEllison post

(blog), 8 September 2022.

[6]. Review

of the Small Amount Credit Contract Laws, Final

Report, (Canberra: Treasury, March 2016), vii–xi.

[7]. Treasury,

‘Small Amount

Credit Contract and Consumer Lease Reforms’, consultations, October 2017.

[8]. Treasury, ‘Small Amount Credit

Contract and Consumer Lease Reforms’.

[9]. Rebekha Sharkie, ‘Payday

lending reform: time to vote on it and move on’, media release, 16 September 2019.

[10]. Madeleine

King, Matters

of Public Importance: Payday Lending, House of Representatives, Debates,

10 October 2018, 10742.

Rebekha Sharkie, ‘Pressure

mounting for payday lending protections’, media release, 3 December 2019.

[11]. Senate

Economics Legislation Committee (SELC), National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2), (Canberra: The Senate, 2020), 2.

The National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 is one example of the Bills that were not debated.

[12]. Australian

Parliament, National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019, homepage.

[13]. Australian

Parliament, National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2), homepage.

[14]. SELC,

National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2), 59.

[15]. SELC,

National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2), 65.

[16]. Andrew

Wilkie, ‘Time

to crack down on payday lending’, media release, 30 November 2020.

[17]. SELC,

National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019 (No. 2), 2.

Australian Parliament, National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Small Amount Credit Contract and Consumer

Lease Reforms) Bill 2019, homepage.

[18]. Australian

Parliament, National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Supporting Economic Recovery) Bill 2020, homepage.

[19]. Financial Rights Legal Centre, Joint submission to Senate Economics

Legislation Committee, 2.

[20]. SELC,

National

Consumer Credit Protection Amendment (Supporting Economic Recovery) Bill 2020

[Provisions], (Canberra: The Senate, 2021), 55.

[21]. Senate