Bills Digest No.

41, 2020–21

PDF version [787KB]

Clare Murdoch

Science, Technology, Environment and Resources Section

Jonathan Mills

Law and Bills Digest Section

20

January 2021

Contents

List of abbreviations

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

Background

Committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Key issues and provisions

Other provisions

List of abbreviations

| AEMO |

Australian Electricity Market Operator |

| ARENA |

Australian Renewable Energy Agency |

| CCS |

Carbon capture and storage |

| CEFC |

Clean Energy Finance Corporation |

| CEFC Act |

Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 |

| CER |

Clean Energy Regulator |

| DER |

Distributed energy resources |

| DISER |

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

| ESOO |

Electricity Statement of Opportunities |

| GRF |

Grid Reliability Fund |

| GW |

Gigawatt |

| ISP |

Integrated System Plan |

| MW |

Megawatt |

| MWh |

Megawatt hour/s |

| NEM |

National Electricity Market |

| NWIS |

North West Interconnected System |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| SWIS |

South West Interconnected System |

| UNGI |

Underwriting New Generation Investments |

| VRE |

Variable renewable energy |

The Bills Digest at a glance

The purpose of the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation Amendment (Grid Reliability Fund) Bill 2020 (the Bill) is

to amend the Clean

Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 (CEFC Act) to establish a

$1 billion Grid Reliability Fund (GRF), and to allow the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation (CEFC) to administer it by:

- enabling

regulations to be made that allow the CEFC to make new types of investments,

including loss-making investments

- expanding

the functions of the CEFC

- establishing

a new category of CEFC ‘GRF investment’ for:

- energy

storage

- electricity

generation, transmission and distribution, and

- grid

stabilisation technologies

- expanding

the definition of low-emission technology under CEFC complying

investment technologies to also include the above categories of technology and

- excluding

the GRF from the CEFC’s requirement to invest at least half of its funds in

renewable energy projects.

While the Bill will allow for the CEFC to make investments

in a broad range of technologies, much of the discussion around the Bill has

focused on the potential for the changes to enable further CEFC investment in

gas powered generation.

Purpose of the Bill

The purpose of the Clean Energy Finance Corporation

Amendment (Grid Reliability Fund) Bill 2020 (the Bill) is to amend the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation Act 2012 (CEFC Act) to establish a

$1 billion Grid Reliability Fund (GRF), and to allow the Clean Energy

Finance Corporation (CEFC) to administer it by:

- enabling

regulations to be made that allow the CEFC to make new types of investments for

the purposes of the GRF, including loss-making investments

- expanding

the functions of the CEFC

- establishing

a new category of CEFC investment—grid reliability fund investments—for

energy storage, electricity generation, transmission and distribution, and grid

stabilisation technologies

- expanding

the definition of low-emission technology, as applicable to all CEFC

investments, under CEFC complying investment technologies and

- excluding

the GRF from the CEFC’s requirement to invest at least half of its funds in

renewable energy projects.[1]

Background

In recent years there have been a number of inquiries into

energy and electricity in Australia.[2]

These inquiries were catalysed by: rising wholesale and retail prices; concerns

around network reliability following the rapid uptake of variable renewable

energy sources and closure of Hazelwood power station; and concerns around

network security following the state‑wide blackout in South Australia in

September 2016.[3]

The Government’s ‘A Fair Deal on Energy’ policy, announced

on 23 October 2018, aims to deliver reliable, secure and affordable

energy, including by:

- maintaining

and increasing supply of reliable electricity

- increasing

domestic gas supplies and

- promoting

efficient investment in energy infrastructure.[4]

On 30 October 2019, as part of this policy, the Government

announced a new $1 billion GRF to be administered by the CEFC.[5]

The GRF would support ‘investment in new energy generation, storage and

transmission infrastructure, including eligible projects shortlisted under the

Underwriting New Generation Investments (UNGI) program.’[6]

(The UNGI is discussed further later in this Digest.)

The Clean Energy Finance

Corporation

The CEFC is a Commonwealth statutory authority established

in 2012 under the CEFC Act.[7]

The object of the CEFC Act and the CEFC is to facilitate increased flows

of finance into the clean energy sector.[8]

The CEFC’s current corporate plan further outlines:

Our purpose of increasing the flows of finance into the clean

energy sector is directed at contributing to Australia’s efforts to reduce

emissions. The scale of the emissions challenge suggests Australia requires

significant new investment across the economy.[9]

The CEFC manages a $10 billion special

account that co-finances and invests in clean energy technologies.[10]

The CEFC Board has statutory responsibility

for decision-making and managing the CEFC’s investments.[11] The CEFC Act

requires investments by the CEFC to be complying investments—investments

that are:

- in clean energy technologies, that is renewable energy, energy

efficiency and low-emission technologies

- solely or mainly Australian-based and

- not in a prohibited technology, that is carbon capture and storage

(CCS) technology, nuclear technology or nuclear power.[12]

The CEFC Board operates and makes its

investment decisions independently of government; however, the CEFC must also

comply with an Investment Mandate,[13] which is issued by the responsible Ministers[14] to give guidance to the

CEFC. The Investment Mandate includes direction on return, risk, financial

instruments, priority investment areas and allocation of investments.[15] The Investment Mandate must

not be inconsistent with the CEFC Act and must not require the CEFC

Board to make any particular investment.[16]

From its election in September 2013 to early 2016, the

Coalition Government maintained a policy to abolish the CEFC.[17]

However, two abolition Bills were rejected by the Senate in 2013 and 2014,

while a third abolition Bill lapsed in April 2016.[18]

The plan to abolish the CEFC was formally abandoned in March 2016.[19]

Since then, the Government has issued a number of new Investment Mandates to

the CEFC and established five programs (listed below) to be funded out of the

CEFC’s $10 billion allocation.

Investment Mandates in force between 2015 and 2018

directed the CEFC to focus on ‘emerging and innovative’ renewable

energy technologies and energy efficiency technologies, such as large-scale

solar, storage, offshore wind and energy efficiency in the built environment.[20] During this time the

Government also introduced a Bill to remove the prohibition on the CEFC

investing in CCS technologies, which lapsed in April 2019.[21]

Since December 2018, the responsible

Ministers have made three more Investment Mandates.[22] The most recent Investment

Mandate, made in May 2020, directs the CEFC to focus on technologies and

financial products as part of the development of a market for firming

intermittent sources of renewable energy generation, as well as supporting

emerging and innovative clean energy technologies.[23] The current Investment

Mandate also encourages the CEFC to prioritise investments that support

reliability and security of electricity supply, and to take into consideration the

potential effect on reliability and security of supply when evaluating

renewable energy generation investment proposals.[24]

The Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction and the

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) have both

indicated an intention to update the Investment Mandate once the Bill is

passed.[25]

In addition, five Government programs are funded out of the CEFC’s $10 billion allocation:

The CEFC Board also formulates written

investment policies which outline its investment strategy, benchmarks and

standards as well as the risk management approach for the CEFC and its

investments.[32]

The CEFC is considered to have been ‘effective in directly

and indirectly facilitating increased flows of finance into a range of clean

energy projects across a number of sectors.’[33]

As at 30 June 2020, the CEFC has committed $8.2 billion in investments with a

total investment value of $27.8 billion, meaning that every CEFC dollar

invested had catalysed additional private investment at a rate of $2.30.[34]

In 2019–20, the CEFC reported a record $942 million in repaid or recouped CEFC

finance, with total repayments over the CEFC’s lifetime amounting to $1.66

billion.[35]

The CEFC estimates the lifetime carbon abatement for CEFC investment

commitments since 2012 to be 220 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent

greenhouse gas (Mt CO2-e).[36]

The CEFC was established alongside ARENA, which provides

grant funding to renewable energy technology projects. Currently, the two

agencies have clearly delineated roles which ‘enable ARENA to develop new and

emerging … technologies to the stage where the CEFC can provide investment

support to accelerate further commercialisation and deployment.’[37]

What is the grid?

The electricity network, or the grid, comprises the

transmission and distribution infrastructure that transports electricity from

generators to homes and businesses (see Box 1). Due to the country’s large size

and concentrated population distribution, Australia does not have a national

interconnected electricity grid. The main electricity grid is the National

Electricity Market (NEM), which consists of 13 distribution networks fed by

five state-based transmission networks in Queensland, New South Wales (NSW)

including the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Victoria, South Australia and

Tasmania, linked by cross-border interconnectors.[38]

The NEM delivers around 80 per cent of all electricity consumed in Australia.[39]

The Northern Territory has three separate grids—the

Darwin-Katherine, Alice Springs and Tenant Creek electricity networks—and

Western Australia has two main grids—the South West Interconnected System

(SWIS) and the North West Interconnected System (NWIS).[40]

Throughout Australia, electricity may also be delivered to localised areas via

small, non-interconnected systems, or microgrids.[41]

Box 1: Electricity supply chain[42]

Generators produce

electricity from a range of sources, such as coal, gas, solar, wind and water. The

generation sector is a competitive market. Generators sell electricity to large

industrial energy users and local retailers via wholesale spot and contract

markets.

Transmission networks

comprise transformers, large towers, high-voltage lines and cables, and

interconnectors that transport electricity large distances across and between

states. Private and state government-owned Transmission Network Service

Providers operate the transmission networks, which are regulated natural

monopolies.[43]

Distribution networks

comprise transformers, poles and wires, and substations that transport and

deliver low-voltage electricity to homes, offices and factories for lighting,

heating and to power appliances. Distribution Network Service Providers operate

the distribution networks, which are also regulated natural monopolies.

Retailers, or

electricity providers, purchase electricity from the wholesale market and

network services from transmission and distribution network service providers,

and then sell them as a package to residential, commercial and industrial

customers. Retail is a competitive market.

Distributed energy resources (DER) are generally small-scale generation units embedded within

the distribution network and behind the meter, such as rooftop solar

photovoltaic (PV) units and home battery systems. DER enables consumers to

generate and/or store electricity for use and to sell excess electricity back

to retailers or offer demand response.

Microgrids enable

local generation and storage, typically at a community scale, and are not

connected to the main grid.

|

Grid transformation

Most of Australia’s electricity infrastructure was built

in the 20th century, designed to generate electricity in a few large power

stations, and distribute it via high capacity transmission lines.[44]

But Australia’s electricity systems are now undergoing a major transformation,

from centralised one‑way systems dominated by fossil fuel generation at

large power stations to dispersed, diverse two-way systems that incorporate

utility-scale and behind-the-meter renewable energy sources.[45]

Australia’s energy system is considered by some to be

undergoing the fastest transformation in the world,[46]

driven by factors such as community concern around climate change, federal and

state government policies, renewable technology improvements and cost

reductions, an aging coal fired generation fleet, and high coal and gas fuel

costs.[47]

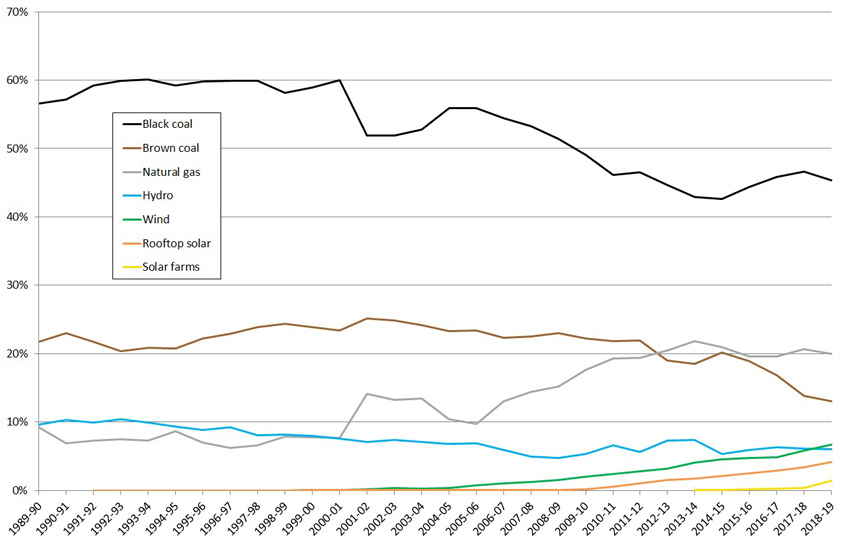

Coal fired generation remains the dominant supply source

in Australia’s electricity system; however, this is changing (see Figure 1). In

the past decade, the contribution of coal fired generation to overall

electricity generation has fallen from more than 71 per cent to just over

58 per cent, while the contribution of wind generation has tripled and the

combined contribution of utility-scale and rooftop solar has gone from

negligible to more than five per cent.[48]

Since 2014, more than 4 GW of coal fired generation left the market, while more

than 7 GW of new renewable generation came online.[49]

Overall the contribution of fossil fuel sources to electricity generation in

Australia has declined more than ten per cent, being replaced by renewable

energy sources.[50]

This trend is expected to continue, with around two-thirds of coal fired

generating capacity in the NEM announced for closure over the next 20 years,

and much of the committed new generation capacity comprising large-scale

renewable energy.[51]

Similarly, recent modelling of the SWIS predicts that, in any scenario, over 70

per cent of generation capacity will be met by renewables by 2040.[52]

Electricity emissions

This transition is an important factor in greenhouse gas

emissions reduction efforts to meet Australia’s Paris

Agreement commitments (to reduce emissions by 26 to 28 per cent below 2005

levels by 2030).[53]

So far, the transition towards renewable energy generation in Australia has

resulted in an 18.3 per cent reduction of emissions generated by the

electricity sector since 2009,[54]

representing around 44 per cent of all emissions reductions over that period.[55]

However, electricity generation is still the highest emitting sector in

Australia, accounting for 32.7 per cent of emissions recorded in Australia’s

National Greenhouse Gas Inventory in the year to March 2020.[56]

The electricity sector now has a number of mature and

demonstrated low- and zero-emissions technologies, including distributed

rooftop solar PV, large-scale wind and solar renewables, large- and small-scale

battery storage, and pumped hydro storage, with large-scale renewables now the

least expensive form of generation capacity to construct and operate.[57]

The CEFC has played an important role in supporting the entrance of renewable

energy sources into the grid, having financed 31 utility-scale solar projects

and 12 wind farms since 2012, totalling more than 3 GW of energy.[58]

The maturity of zero emissions technologies in the grid, the fact that

electricity is utilised for energy supply across the economy, and additional

opportunities for electrification, mean that the electricity sector has the

potential to continue to deliver more than a proportional share towards meeting

emissions reduction targets.[59]

Ongoing decarbonisation of the electricity sector is also considered a

precondition for the decarbonisation of other high emitting sectors, such as

the transport, manufacturing and building sectors.[60]

Figure 1: share of electricity generation by technology, 1989–90 to 2018–19

Source: Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources

(DISER), Australian

energy statistics 2020: Table O, DISER, Canberra, 2 October 2020.

The case for grid investment

The energy transition has created challenges in delivering

critical power system needs of maintaining reliability and security, while

enabling consumer affordability and meeting emissions outcomes.[61]

Reliability and security

A reliable power system has the generation, demand

response and transmission network capacity to supply enough electricity to meet

customer demand to a high probability.[62]

A secure power system operates within technical limits and can withstand faults

and disturbances, such as the loss of a transmission line or the unexpected

disconnection of a large generator.[63]

A power system that breaches operating limits may pose a risk to the safety of

individuals, damage equipment and lead to blackouts.[64]

Maintaining both reliability and security requires the

power system to be in balance by continuously matching supply with demand, and

constantly managing technical parameters such as voltage and frequency.[65]

As energy is not generally stored in the grid, this is done in real-time. In

the NEM, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) maintains this balance

via a five‑minute generation dispatch cycle, as well as through markets

and agreements for ancillary services, which can be directed to rapidly

increase or decrease output to maintain system security.[66]

Operating the system in this way requires dispatchability and predictability.[67]

Historically, demand followed a predictable pattern, and

electricity supply has been provided by dispatchable, synchronous generators,

such as large coal fired, gas powered and hydro-electric generators.

Dispatchable generators can be directed to operate on demand, with

fast-response options able to respond to, or ‘firm’, sudden changes in demand

or supply. Synchronous generators have large turbines that rotate in

synchronism with grid frequency. This provides grid stability services such as

inertia and system strength, [68]

which increase resilience to disturbances and help maintain a stable and secure

power system.[69]

The energy transition means that supply and demand

conditions are projected to become more volatile, which presents challenges to

maintaining system reliability and security.[70]

For example:

- the

reliance of wind and solar generation on weather patterns can result in sudden

changes in output and demand, requiring fast-response dispatchable generation

to fill supply gaps when light levels or wind speeds are low[71]

- recent

and expected closures of Australia’s ageing fossil fuel plant fleet, as well as

existing plants becoming more prone to outages due to plant breakdown,

deteriorating performance, and maintenance and repair work, has raised concerns

of potential generation shortfalls[72]

- an

increased proportion of wind and solar generation, which connects to the grid

via non-synchronous inverters, has created concerns around the possibility of

increased system disturbances due to inertia shortfalls and weak system strength[73]

and

- the

popularity of rooftop solar PV and other DER is resulting in major changes to

demand patterns and, in some cases, presents capacity and security concerns for

the distribution grid.[74]

Further challenges to reliability and security are

presented by the ‘increasing frequency, extremity and scale of climate-induced

weather events and other emerging threats’ that affect generation and

transmission infrastructure.[75]

The increasing volatility of supply and demand conditions

has resulted in an increased need for flexible management of the grid to

maintain system reliability and security. Since 2017, AEMO has increasingly had

to intervene in the NEM to manage reliability and security events. These

interventions have included, for example, deploying contracted standby

strategic reserves, issuing directions to dispatchable generators to increase

output, constraining renewable generation or transmission lines, or, as a last

resort, shutting down parts of the network (load shedding).[76]

However, based on current and committed generation and transmission investment

alone, the NEM is not expected to experience reliability risks until 2029–30

(when the Vales Point coal fired power station is scheduled for closure).[77]

Integrating renewables

Current grid infrastructure is considered a major

impediment to further investment in grid-scale renewables. The optimal location

requirements of grid-scale wind and solar generation, as well as their rapid

uptake and distributed nature, have resulted in integration issues as a result

of weak proximate transmission network capacity.[78]

The NEM transmission grid also has a weak level of interconnections, reducing

the ability of the grid to provide reliability and security services between

regions, and meaning disruption of an interconnector can quickly lead to the

isolation of a region.[79]

The Clean Energy Regulator (CER) considers ‘the ability of

Australia's electricity grid to transmit renewable electricity from production

to areas of demand is currently the major limiting factor to further growth’ in

renewable generation investment.[80]

The Clean Energy Council’s regular survey of investment confidence within the

clean energy industry has identified grid connection, network access and

transmission concerns as consistently the top challenge cited by businesses

since July 2019.[81]

Improved transmission and distribution network capacity

will be critical in supporting increased variable renewable energy (VRE)

sources, by reducing transmission losses and congestion costs, and allowing

more reliable and improved levels of transfer of electricity between regions.[82]

This would mean that power from geographically diverse renewable energy

resources could be transferred from regions where the weather is favourable to

regions where it is not, at a given time, thus reducing, or smoothing, the

overall variability of renewable electricity supply.[83]

Network investment must be balanced with costs, as over-investment in some

regions in Australia has resulted in significant increases in electricity

prices.[84]

However, AEMO notes:

If … VRE is coordinated with strategic investments in the

transmission network, the greater resource diversity and competition will

reduce the costs of supply. This in turn should result in downward pressure on

electricity bills, assuming effective wholesale and retail markets.[85]

Grid technologies

AEMO’s

Integrated System Plan (ISP) provides a roadmap for NEM future generation and

grid infrastructure investments. The most recent ISP modelling, published in

June 2020, suggests that the optimal grid is one dominated by renewable energy

sources and supported by a diverse range of complementary technologies:

… the least-cost and least-regret transition of the NEM is

from a system dominated by centralised coal-fired generation to a highly

diverse portfolio of behind-the-meter and grid-scale renewable energy

resources. These must be supported by dispatchable firming resources and

enhanced grid and service capabilities, to ensure the power system remains

physically secure.[86]

Dispatchable generation and storage

AEMO’s Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO)

identifies an additional 1,480 MW of firm capacity will be needed to enter the NEM

in the next decade to meet the existing reliability standard.[87]

The ISP predicts that, over the next 20 years, 6–19 GW of new dispatchable

resources will be required to firm a grid increasingly dominated by

intermittent renewable energy resources.[88]

Fast-response dispatchable technologies considered in the ISP include

utility-scale pumped hydroelectricity (pumped hydro) and battery storage,

demand response and small-scale distributed batteries, and gas powered

generation.

Grid-scale electricity storage technologies such as

batteries and pumped hydro are expected to comprise a significant proportion of

new investment in dispatchable resources.[89]

Battery storage is becoming increasingly economically viable as technology

costs reduce, with at least five batteries now operating in the NEM.[90]

Pumped hydro is the most mature form of electricity storage in Australia, with

schemes in NSW and Queensland in operation since the 1970s.[91]

The Australian Government has committed support to new pumped hydro storage,

including the Snowy 2.0 project and the Tasmanian ‘Battery of the Nation’

proposal.’[92]

The Government’s recent First Low

Emissions Technology Statement identifies grid-scale storage as ‘a

critical element of Australia’s future electricity system.’[93]

Storage has the potential to deliver significant emissions reductions by

enabling a greater penetration of renewable energy in the grid, and offsetting

higher emitting dispatchable generation sources.[94]

Demand-side participation, where customers reduce or shift

electricity use from high demand and price periods, is also predicted to play

an increasing role in the grid in coming years.[95]

Technologies include automated home energy management systems and appliances

with smart grid technologies, home battery systems, virtual power plants (where

DER from numerous homes are aggregated and operated as a single system), and

electric vehicles (which, in the future, are expected to provide

‘vehicle-to-grid’ storage, providing electricity back to the grid at periods of

high demand).[96]

Hydrogen technologies, although at an emerging stage, may also

have future potential for electricity storage and dispatchable generation.[97]

Hydrogen has also been proposed as a potential alternative to diesel generators

in microgrids, and as a blended fuel with gas, which could lower the emissions

profile and extend the economic life of gas powered generators[98]

(although the emissions intensity of hydrogen is affected by production

method).[99]

The First Low Emissions Technology Statement considers hydrogen to

present a competitive option for firming electricity at $2 per kilogram.[100]

Gas powered generators typically provide ‘flexible’ or

‘peaking’ power, ramping up quickly to cover supply shortfalls during high

demand periods, or to provide longer-term firming overnight or during long

periods of low wind.[101]

The AEMO ISP considers that existing gas powered generators will play a

critical role in complementing VRE and storage, particularly once significant

amounts of coal fired generation capacity is retired.[102]

However, the ISP considers new gas powered generation to present an

economically viable dispatchable resource option only if gas prices are low and

battery costs remain high.[103]

Efficient gas powered generation has typically been considered to be less than

half as emission intensive as coal fired generation.[104]

However, this is controversial, with recent studies suggesting this could be a

significant underestimation.[105]

The Australian Government has shown considerable support for gas powered

generation (see sections below).[106]

Grid stabilisation technologies

The dispatchable technologies listed above also provide

various services to help maintain grid stability and security. For example, gas

powered generators and pumped hydro plants are synchronous and thus inherently

provide inertia and system strength.[107]

Grid-scale battery storage can provide rapid, accurate ancillary services to

help stabilise technical issues in the grid, such as frequency control

services.[108]

The ability of large-scale battery storage to provide virtual inertia, which

emulates services provided by synchronous generators, through new inverter

technology is currently being developed, with two demonstration projects

recently completed in South Australia.[109]

Additional technologies are also being deployed to help

stabilise the grid and maintain system security. For example, synchronous

condensers (large rotating electric machines that closely resemble synchronous

generators) are a mature technology that presents a solution to bolster grid

stability as large synchronous generators leave the market.[110]

In South Australia, the installation of four synchronous condensers is

currently underway.[111]

The capability of wind and solar farms to provide stability services is also

evolving, with improvements in inverter based generation technology allowing

rapid response to changes in supply and demand, and making a limited

contribution to system strength.[112]

Network investment

The ISP outlines an optimal development pathway for the

NEM transmission network, which includes nine near-term critical projects and

nine longer-term projects to augment the transmission grid.[113]

Projects include upgrades of existing infrastructure, as well as new

interconnectors, cables and network augmentations to support the development of

renewable energy zones (REZs), which are ‘high-resource areas … where clusters

of large-scale renewable energy projects can capture economies of scale as well

as geographic and technological diversity in renewable resources.’[114]

The ISP considers:

As long as augmentation costs are kept to an efficient level,

strategically placed interconnectors and REZs, coupled with energy storage,

will be the most cost-effective way to add capacity and balance variable

resources across the whole NEM.[115]

The Government has committed funding to a number of ISP

transmission projects, including the HumeLink transmission upgrade in NSW, the

Queensland-NSW Interconnector (QNI) project, the Project EnergyConnect

interconnector between South Australia and NSW, the Victoria-NSW Interconnector

(VNI) West project, and the Marinus Link transmission cables between Victoria

and Tasmania.[116]

The

Underwriting New Generation Investments (UNGI) program

On 23 October 2018, the Government announced plans to

introduce the UNGI program to underwrite investment[117]

in new power generators.[118]

The program aims to support new dispatchable energy generation projects for the

NEM to lower prices and increase reliability.[119]

According to the Government, the UNGI was developed in response to

recommendation four of the ACCC Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry.[120]

The inquiry found that an entrenched lack of competition in NEM generation

markets was a primary driver of high electricity prices in Australia, and

recommended, among other things, that the Government enter into low fixed-price

energy offtake agreements for new generation projects that met qualifying criteria.[121]

The Government undertook an 18 day period of consultation

on the program, including the release of a consultation

paper which outlined a number of possible mechanisms for attracting

investment.[122]

The Government received 66 submissions for projects during a six week

Registrations of Interest period, and in March 2019 announced that 12 projects

had been shortlisted. This consisted of six pumped hydro projects, five gas

projects and one coal upgrade project.[123]

Initial support terms to underwrite two of the shortlisted

gas projects were announced in December 2019.[124]

Funding for the coal upgrade project was also slated in the 2020–21 Budget,

although the exact funding amount was not for publication.[125]

According to the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER),

the other shortlisted projects are still under consideration for UNGI support.[126]

DISER also notes:

The government will continue to engage with proponents of

projects that have not made the shortlist, but may meet the program’s

objectives and eligibility criteria. This will support the development of a

pipeline of mature projects that the government can work with over the life of

the program.[127]

On 23 April 2020, independent MP Zali Steggall referred

the UNGI program to the Auditor‑General, based on concerns around the

program’s legislative basis, lack of assessment guidelines or criteria, and

lack of clear process in the program’s development and implementation.[128]

Following this, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) included the UNGI

program as a potential topic in the 2020–21 Annual Audit Work Program.[129]

Since the announcement of

the GRF, and intentions for it to fund UNGI projects, DISER states:

The government will only refer

UNGI projects to the Grid Reliability Fund that reflect the CEFC’s legislative

mandate. The CEFC will not invest in coal projects.

Further announcements on shortlisted UNGI projects will be

made as the government reaches agreements with individual project proponents.

In the longer term, the intention is for the CEFC to be the

lead UNGI delivery agency – with the exception of coal projects. When the

legislation allows, UNGI projects will be referred to the CEFC. The government

will manage this transition to ensure no impact on program delivery.[130]

Related energy announcements and gas-led recovery

In the weeks following the introduction of the Bill, the

Government made a number of energy announcements, which provide further context

for the Bill. These announcements included:

- plans

for a gas-led economic recovery from the recession caused by the COVID-19

pandemic, including a commitment to identify priority gas pipelines and

critical infrastructure, and to develop an Australian Gas Hub in Queensland[131]

- a

target for the private sector to deliver 1,000 MW of new dispatchable energy to

the NEM by the 2023–24 summer (coinciding with the expected closure of the

coal-fired Liddell power station), with a promise that, if final investment

decisions are not made by April 2021, the Government will progress plans for

Commonwealth-owned company Snowy Hydro Ltd to build a gas-fired generator[132]

- a

commitment to work with state governments to accelerate three priority

transmission projects identified in the AEMO Integrated System Plan: the

Marinus Link, and the Project EnergyConnect and VNI West interconnectors[133]

- a

$1.9 billion package in low emissions technologies, primarily delivered to

ARENA as baseline funding, but also including $50 million towards a Carbon

Capture Use and Storage Development Fund, $70.2 million to set up a hydrogen

export hub, and $67 million to install microgrids in regional and remote

communities[134]

- $28.5

million to fund energy infrastructure in Western Australia, including

investment in a 100 MW/200 MWh battery for the SWIS and extension of

Western Australia’s microgrids program[135]

and

- a

commitment to introduce NEM market reforms, to be developed by the National

Cabinet Energy Reform Committee, to ‘take account of the increasingly

distributed nature of generation and better recognise the critical stabilising

role played by dispatchable generation’.[136]

Additionally, in the 2020–21 Budget, the Government

committed to fund or underwrite a number of transmission, storage and

generation projects as part of the JobMaker Plan, including to:

- provide

loan funding to progress the Marinus Link project

- provide

funding for the CopperString 2.0 transmission project to connect the North West

Minerals Province in Queensland to the NEM

- provide

funding for the SWIS Big Battery project in Western Australia

- underwrite

early works associated with the Project EnergyConnect and VNI West transmission

projects and

- underwrite

upgrades to the Vales Point coal fired power station—a project shortlisted for

the UNGI program.[137]

The Government also released the First

Low Emissions Technology Statement, which identified five priority

technologies for Government investment: clean hydrogen; electricity from

storage; low carbon steel and aluminium; CCS; and soil carbon.[138]

In support of this statement, the Government has flagged that, among other

things, it will:

- require

the CEFC, as well as ARENA and the CER, to focus on accelerating the five

priority technologies and

- introduce

legislative reforms to ensure the CEFC, as well as ARENA, is able to invest in

the priority technologies.[139]

These intentions align somewhat with recommendations of

the Report of the Expert Panel Examining Additional Sources of Low Cost

Abatement (King Review). In September 2019, the Expert Panel, chaired by

former President of the Business Council of Australia and Managing Director of

Origin Energy, Mr Grant King, was appointed to provide advice to the Government

on how best to incentivise low cost emissions reduction opportunities across

the economy.[140]

The King Review recommended that the CEFC (as well as ARENA) be provided ‘with

an expanded, technology-neutral remit so they can support key technologies across

all sectors’.[141]

As outlined earlier in this Digest, the CEFC Act

currently prohibits the CEFC from investing in CCS technology. The Bill does

not change that prohibition. As such, enabling the CEFC to invest in CCS would

require the introduction of further amendments to the CEFC Act. The

Department indicated in October 2020 that it was in the early stages of

preparing this additional legislation.[142]

Committee consideration

Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee

The Bill was referred to the Senate Environment and

Communications Legislation Committee (the Committee) for inquiry and report.

The Committee received 45 unique submissions, as well as approximately 700 form

letters and more than 4,500 short statements. A public hearing was also held in

Canberra (see ‘Position of major interest groups’ section).[143]

The Committee’s majority report recommended the Bill be

passed.[144]

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) and the Australian Greens (Greens) both

provided dissenting reports that recommended amendments to the Bill (see

‘Policy position of non-government parties/independents’ section).[145]

Further details of the inquiry can be found at the inquiry

homepage.

Senate Standing Committee for

the Scrutiny of Bills

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee (Scrutiny Committee)

considered the Bill in its report dated 2 September 2020.[146]

The Scrutiny Committee raised concerns and requested further advice from the

Minister in relation to the use of non-disallowable delegated legislation for

significant matters. The Scrutiny Committee noted particular concern ‘that

details of the investment criteria for the Fund are being left to

non-disallowable delegated legislation and will therefore not be subject to

effective parliamentary oversight.’[147]

The Scrutiny Committee questioned whether the Bill could be amended to set out

the criteria that a GRF investment must meet in the primary legislation, or

provide that Investment Mandates made by the Minister are subject to the

disallowance process.[148]

Minister’s response

In response to the Scrutiny Committee, the Minister

stated:

- the

non-disallowable Investment Mandate has been a feature of the CEFC Act

since its introduction and its use for the proposed GRF replicates the existing

role of the Investment Mandate in relation to the CEFC’s original fund

- the

legislative concept of grid reliability investment is bounded by the

definition of clean energy technologies contained in the Act and the

Investment Mandate cannot be used to expand that statutory limitation

- it

is long-standing practice that Ministerial directions to government bodies are

non‑disallowable

- Investment

Mandate directions provided under a wide range of similar Commonwealth

legislation are also non-disallowable

- the

evolving nature of challenges to grid reliability and security necessitate the

Investment Mandate to ensure that issues can be considered and updated as

necessary, without requiring amendment of the Act

- the

Investment Mandate cannot override the operational independence of the CEFC,

nor require the CEFC to make, or not make, a particular investment and

- the

Investment Mandate is an essential tool for the Government to give direction to

the CEFC in the performance of its legislative functions.[149]

The Scrutiny Committee noted and responded to the

Minister’s comments in its report dated 7 October 2020.[150]

The Scrutiny Committee left to the Senate as a whole further consideration of the

appropriateness of leaving criteria for which investments can be funded from

the GRF to be determined in non-disallowable delegated legislation. This issue

is addressed further in the ‘Key issues and provisions’ section of this Digest.

Policy position of

non-government parties/independents

ALP

On 1 September 2020, the ALP indicated that it ‘supports

the expansion of the CEFC to help deliver a modern electricity grid, but not

for gas generation investments’.[151]

The ALP foreshadowed proposed amendments to the Bill to ensure the CEFC retains

the requirement to invest in projects that provide a return, and said it would

block attempts to establish additional Ministerial powers.[152]

Shadow Minister for Climate Change and Energy Mark Butler said that, if these

amendments are unsuccessful, the ALP will vote against the Bill.[153]

This position is reiterated in the ALP Senators’

dissenting report to the Committee inquiry into the Bill.[154]

The dissenting report proposed the Bill be amended to remove the power to

define new investment types through regulation and retain the current

definition of low-emissions technology in the CEFC Act:

While Labor supports those parts of the bill that are purely

focused on increasing energy security and reliability through network and

storage investment, two features of the current bill are sufficiently

problematic to warrant amendment in Labor’s view. Put most broadly, as well as

encouraging more transmission and security investment, this bill dilutes both

the CEFC’s focus on emissions reduction and its financial independence. These

two characteristics—a clear commercial investment focus with a clear commitment

to financial independence, and a focus on genuine emissions reduction—are the

defining characteristics of the CEFC and as both are severely undermined by

this bill, Labor Senators cannot support the bill in its current form.[155]

The Greens

The Greens do not support the Bill in its current form,

describing ‘subsiding [sic] gas through the green energy bank [as] like pouring

money from the health budget into asbestos.’[156]

Greens Leader Adam Bandt has reportedly described the Bill as a ‘Trojan horse

for coal and gas’ and stated ‘[r]edefining gas as a “low-emissions technology”

would let gas corporations access $billions in public funding intended for

renewables.’[157]

The Greens dissenting report raised concerns as to the

Bill’s impact on the CEFC’s independence:

Supporting this bill as currently drafted will weaken the

independence of the CEFC with the Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister able

to insert himself in the middle of investment decisions. Furthermore, the

creation of a legislated definition of ‘low-emissions technology’ will allow

the Minister to overrule the current CEFC Board’s control over what it

considers to be eligible investments in non-renewable technologies.[158]

The Greens recommended:

- UNGI

projects be funded through separate legislation, rather than the CEFC Act

- changes

to the definition of low emissions technology be removed from the Bill

- the

current definition of investment in the CEFC Act be retained

- additional

amendments be made to make the Investment Mandate disallowable by parliament

- the

proposed amendment to exclude GRF investment earnings from being able to be

transferred to ARENA at the request of the CEFC be removed from the Bill and

- additional

amendments be made to include ‘fossil gas’ and ‘coal’ as prohibited

technologies.[159]

Zali Steggall

Independent MP Zali Steggall has criticised the Bill in

numerous social media posts,[160]

and has stated that, if the Bill is enacted, ‘it will pollute Australia's clean

bank by allowing it to invest in gas and loss-making projects.’[161]

As noted above, Ms Steggall has referred the UNGI program to the Auditor-General,

over concerns as to a lack of transparency and accountability around the

program.[162]

Centre Alliance/Senator Griff

Centre Alliance Senator Stirling Griff reportedly

supported referral of the Bill to inquiry, noting:

At first glance I don’t see any significant issues with it,

but the [Environment and Communications Legislation Committee] inquiry is

important to understand the full range of effects. [The] CEFC is one of the

most effective government agencies. Centre Alliance absolutely prefers

investments are made by an independent agency at arm’s length from government

...[163]

Katter’s Australian Party

Katter’s Australian Party MP Bob Katter has not formally

stated a position on the Bill, although, in April 2020, he called on the

Government to expand the investment remit of the CEFC, to include ‘all types of

infrastructure and industry’.[164]

Position of major interest

groups

A number of interest groups made submissions to the

Committee’s inquiry, including conservation and community services

organisations, investment and industry groups, and academics, as well as former

Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the CEFC Oliver Yates. Many supported

additional funding for the CEFC or the overall policy objective of the GRF, but

raised concerns over various aspects of the Bill.[165]

The Bill was generally viewed in the context of the Government’s wider energy

announcements, particularly its plans for a gas-led economic recovery. Many

submissions understood the Bill’s intention to be to allow and, ultimately

direct, the CEFC to invest in gas powered generation and fossil fuel projects.[166]

Most submissions opposed this intention, with the exception of the Australian

Pipelines and Gas Association (APGA), Australian Petroleum Production and

Exploration Association (APPEA), and the Australian Industry Group (Ai Group).[167]

Another key concern raised by a number of submissions was

that the Bill would impact on the CEFC’s independence, by providing additional

powers to the Minister to direct CEFC investments.[168]

This was disputed by the Ai Group, which considered:

… that independence would be preserved—that the CEFC would

have greater scope to choose individual investments that might not in fact have

a return, but the minister would remain unable to direct it to make particular

investments.[169]

An overview of additional key concerns raised in

stakeholder submissions is outlined in Table 1 below. Further detail is

included in the ‘Key issues and provisions’ section of this Digest.

Table 1: Key issues

raised in major stakeholder submissions to the Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee

| Issue |

Stakeholder/s |

| Opposed/Expressed concern |

Supported/Not concerned |

|

Exempting the GRF from the CEFC requirement to invest at

least half its funds in renewable energy.

|

Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF), 350.org,

Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens, Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of

Victoria and Tasmania and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Australia

Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS)

The Australia Institute

|

Australian Pipelines and Gas Association (APGA)

Ai Group

|

|

Changing the definition of low-emissions technology.

Concerns included:

- that it

is intended to require the CEFC to invest in fossil fuel projects and

- that

the expanded definition is unnecessary as the CEFC can already invest in grid

technologies.

Stakeholders that supported this change commended a

technology-neutral approach.

|

ACF, 350.org, Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens,

Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania and WWF Australia

Associate Professor Elizabeth Thurbon, Dr Sung-Young Kim,

Emeritus Professor John Mathews and Associate Professor Hao Tan

Mr Oliver Yates

ACOSS

The Australia Institute

Climate Council of Australia (Climate Council)

Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR)

|

APGA

Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration

Association (APPEA)

|

|

The new term low emissions energy system (as added

to the definition of low-emissions technology) is not defined by the

Bill. Concerns included:

- that

this introduces excessive ambiguity and opacity

- that

the term low emissions energy system could be determined by the

non-disallowable Investment Mandate rather than the CEFC Board.

|

ACF, 350.org, Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens,

Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania and WWF Australia

Ai Group

The Australia Institute

Climate Council

Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC)

|

|

|

Expanding the definition of investment to include

new types of investment as per new regulations—particularly that this could

include loss-making investments. Concerns, included:

- that

this could result in the CEFC underwriting loss-making fossil fuel projects

- that

this provides unnecessary additional Ministerial powers

- that

this will undermine the investment skills of CEFC staff and

- that

this is the remit of ARENA in providing grants.

|

ACF, 350.org, Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens,

Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania and WWF Australia

Mr Oliver Yates

The Australia Institute

Climate Council

ACCR

|

Ai Group

|

|

Transfer of the UNGI program to the CEFC.

|

ACF, 350.org, Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens,

Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania and WWF Australia

ACOSS

The Australia Institute

|

|

|

Expansion of the CEFC’s functions.

|

The Australia Institute

|

IGCC

|

The CEFC, as well as DISER and the CER, also made

submissions to the Committee in regards to the Bill, with the CEFC stating it

‘stands ready, willing and able to administer the GRF including UNGI elements

which may fit within the CEFC Act and Investment Mandate’.[170]

In evidence to the Committee, a representative of DISER argued that many of the

concerns with the Bill arose from ‘a number of misconceptions about the effect

of this bill’.[171]

The Northern Territory Department of Industry, Tourism and

Trade also made a submission, welcoming funding opportunities for projects

located in the Northern Territory.[172]

After the release of the Committee’s report it was reported

that Mr Yates and four other former board members and executives of the CEFC

and ARENA—former CEFC chair Jillian Broadbent, former CEFC board member

Professor Andrew Stock, former ARENA chair Greg Bourne, and former ARENA chief

Ivor Frischknecht—had written to MPs recommending they vote against the Bill in

its current form.[173]

The letter, also signed by energy experts Simon Holmes à Court, Geoff Cousins

and Miles George, states:

We support additional funding for the CEFC, including the $1

billion proposed through the CEFC Amendment Grid Reliability Fund Bill 2020

(the Bill), however this funding is not currently critical and should not come

at the expense of the CEFC’s core mission or commercial success.

We do not support changes to the CEFC’s legislation that

undermine its independence, low emissions remit, commitment to profitability,

or its avoidance of fossil fuels as part of a clear commitment to assist in the

reduction of Australia’s climate emissions.[174]

Financial implications

The Bill will increase the CEFC’s appropriation by $1

billion through the establishment of a GRF special account, which may be

increased through regulations. The GRF must also be credited with the CEFC’s

surplus money related to GRF investments that is returned under section 54

of the CEFC Act. The money appropriated to the GRF is to be accounted

for separately to the CEFC’s original $10 billion appropriation. The

Explanatory Memorandum states that money appropriated to the GRF will not be a

reallocation of the CEFC’s original appropriation.[175]

While the Bill provides for expanding the definition of

investment through regulations to include activities that may not make a

return, the Explanatory Memorandum states that it is expected that the GRF, as

a whole, provides a return.[176]

The Bill:

… has a financial impact, both actual and prospective, in

relation to the CEFC. However, the impact on the budget is positive because the

investments made through the GRF will create a return for the Commonwealth over

the long-term.[177]

Under section 50 of the CEFC Act, the CEFC is able

to request that ARENA receive payment of a specified amount, paid out of the

earnings of the CEFC. The Bill inserts an amendment to exclude GRF investment

earnings from this arrangement.[178]

Administrative funding for the GRF is appropriated

separately to the CEFC by DISER.[179]

Special appropriations

The GRF will be established as a special account for the

purposes of the Public

Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act).

A special account is a limited special appropriation that notionally sets aside

an amount that can be expended for specific purposes.[180]

Under the PGPA Act, if an Act establishes a special account and

identifies the purposes of the account, then the Consolidated

Revenue Fund is appropriated for expenditure for those purposes, up to the

balance of the special account at the time.[181]

Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth) (Parliamentary Scrutiny Act),

the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and

freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in

section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[182]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights stated

that it had no comment on the Bill.[183]

Claim of

incompatibility

The Environmental Defenders Office, acting on behalf of

Greenpeace Australia Pacific (Greenpeace), has written to the Committee, as

well as the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR) and the Minister

for Energy and Emissions Reduction. The letter argues that the Bill’s Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights fails to consider the impacts on human

rights that will be affected by climate change, which are relevant based on

Greenpeace’s view:

… that the effect of the CEFC Amendment Bill is to redirect

funds away from renewable energy, and instead to fossil fuel projects,

particularly gas. In this way, our client considers that the CEFC Amendment

Bill is likely to result in an increase of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions

at a time when immediate and deep cuts in emissions are required in order to

meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and avoid the most dangerous impacts of

climate change.[184]

On this basis, the letter requests the Bill be remitted

back to Parliament for reconsideration of its compliance with the Parliamentary

Scrutiny Act, and/or for reconsideration by the PJCHR.[185]

Key issues and provisions

The Bill introduces amendments to the CEFC Act to

establish a $1 billion GRF special account and to establish some rules

around how the CEFC can administer investments under the fund. The amendments

also make clear that the GRF is in addition to the existing $10 billion CEFC

funds, and is excluded from the requirement that at least half of those funds

must be invested in renewable energy technologies. An amendment also expands

the scope of the definition of low-emission

technology that the CEFC Board may invest in.

New definition of ‘investment’

Item 3 replaces the existing definition of investment

in section 4 of the CEFC Act. At present an investment is defined

by section 4 as ‘any mode of application of money or financial assets for the

purpose of gaining a return’, including giving a guarantee. This definition

applies to all investments made by the CEFC under its investment function in

Part 6 of the CEFC Act.

The proposed definition maintains the applications made

for the purpose of gaining a return in the same terms as the existing

definition, but adds as an alternative any relevant thing prescribed by

regulations, in the following terms:

(c) doing a

thing prescribed by the regulations for a purpose related to making a grid

reliability fund investment.

A definition of grid reliability fund investment is

also inserted by the Bill and discussed further below.

As some submissions (summarised above) to the Environment

and Communications Legislation Committee noted, the ability to prescribe a

‘thing’ by regulation could significantly broaden the scope of the investment

function of the CEFC. DISER has stated that the new ‘prescribed investment

types may not necessarily provide a return in the short term, could be revenue

neutral, or could create a contingent liability for certain risks which allows

a clean energy investment to proceed.’[186]

In particular, the regulations could be used to permit GRF

related investments that do not make a return. The Explanatory Memorandum

states that such an expansion of the investment function may be necessary to

implement the GRF, for example through a particular type of revenue floor

arrangement underpinning a GRF investment, but that it is intended that such

things would be defined narrowly so that ‘the GRF as whole provides a return to

the Government.’[187]

As any new investment type prescribed as a thing under

this definition would be made by regulations, changes would be subject to the

standard parliamentary disallowance

process.[188]

Investment instruments

Currently, CEFC investments are made in accordance with

the CEFC Act, the Investment Mandate, and a set of investment policies

formulated by the Board under section 68 of the Act. Investment instruments the

CEFC can currently use include: senior debt; subordinated debt; preferred

equity/convertible debt; common equity; interests in pooled investment schemes,

trusts and partnerships; and net profits interests, royalty interests, and

entitlements to volumetric production payments.[189]

The CEFC is able to provide concessional loans and guarantees, although this is

limited by the Investment Mandate.[190]

The CEFC must carry out its investment activities while

seeking to achieve a target performance in accordance with the portfolio

benchmark return and risk profile established in the Investment Mandate. The current Investment Mandate, issued in May

2020, requires the Board to target an average return of the five-year

Australian Government bond rate +3 to +4 per cent per annum over the medium to

long term as the benchmark return of the portfolio.[191]

However, the targeted rate of return is different for investments made under

the Clean Energy Innovation Fund and the Advanced Hydrogen Fund, which both

have a target average return of at least the five-year Australian Government

bond rate +1 per cent per annum.[192]

Rationale for new investment types

DISER’s submission outlines the rationale for expanding

the types of investments that can be made by the CEFC:

Such instruments may be necessary to support the development

of new transmission links and the establishment of Renewable Energy Zones. For

example, CEFC may need to underwrite the early feasibility works, fill a

financing gap where other investors are not willing to accept deferred returns,

or carry the risk of delays in new generation being deployed to support the

revenue requirements of a Renewable Energy Zone.

The amendment will also facilitate the CEFC’s involvement in

the Underwriting New Generation Investments (‘UNGI’) program and similar

initiatives into the future. The UNGI program … addresses an identified market

failure that there are insufficient long-term offtake agreements available in

the market to underwrite new generation projects.[193]

DISER also notes the CEFC will retain its discretion, with

the proposed change ‘simply increasing the number of support tools at the

CEFC’s disposal.’[194]

The CEFC’s submission notes:

… that the Explanatory Memorandum of the GRF Bill states

that, “overall, it is important that the GRF as a whole provides a return to

the Government”. In doing so, the CEFC will continue to invest the GRF funds

responsibly and manage risk prudently.[195]

Key issue—investments without a return

Stakeholders raised significant concerns in regards to the

CEFC being able to make loss-making investments. For example, Mr Yates strongly

opposed amendments to enable the CEFC to make investments without a return,

raising concerns that this will ‘threaten the CEFC’s successful business model

by undermining its commerciality, independence, culture, staffing and highly

specialised skills.’[196]

Mr Yates also argued that ARENA, as a grant making body, is better placed to

make such investments.[197]

The Climate Council also argued that the CEFC ‘is not an appropriate vehicle

for providing financial support to loss-making endeavours.’[198]

The Ai Group, however, considered the amendment to be

‘appropriate’:

… the ability to offer one-sided support may be useful in

supporting more innovative, and risky, projects. The continuing requirement to

achieve portfolio returns serves as a firm constraint on the overall scope of

risk and non-return arrangements that CEFC could contemplate.[199]

Key issue—additional Ministerial powers through

regulations

A number of submissions raised concerns that this

amendment could be used by the Minister to direct CEFC investments. For

example, a joint submission by the Australian Conservation Foundation, 350.org,

Greenpeace Australia, Solar Citizens, Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of

Victoria and Tasmania and World Wildlife Fund (ACF and other organisations)

raised concerns that this would infringe on the CEFC’s independence and

credibility:

Loss-making investments are contrary to the core mission of

the CEFC, and such ministerial direction to fund particular loss-making

activities would be a clear infringement on the independence of the CEFC and its

Board.

By allowing loss-making investments directed by the

designated Minister, there is a clear risk that the Grid Reliability Fund could

be mis-used to fund the Minister's personally preferred projects. At the very

least these proposed changes would unnecessarily put public funds at risk and

jeopardise the CEFC’s investment reputation, which is critical to the

credibility, trust and partnerships the CEFC has built across the investment

community.[200]

The Climate Council expressed similar concerns, stating:

… there is no reason that the Minister should have the unfettered

power to determine how and where loss-making ‘investments’ should be made.[201]

The Australia Institute considered:

There is some logic behind this (for example, the amendment

may allow investment in transmission lines – that alone may not make a return

on investment). However, by providing the Minister with the power to direct

which loss-making profits can be made, the Bill also opens up the possibility

of the CEFC becoming a loss-making underwriter of fossil fuel projects.[202]

However, the CEFC submission notes:

As set out in the CEFC Act, Investment Mandate and the PGPA

Act, the Board is accountable for investment decisions, independent of

Government. As such, it has responsibility for overseeing the efficient and

effective operation of the CEFC, including prudent oversight and governance of

investment decisions and risk management.

The CEFC notes that, with respect to the GRF Bill, the

Explanatory Memorandum states that it, “will not change the CEFC’s ability to

make individual investment decisions independent of Government”.[203]

A representative of DISER also addressed these concerns

during the Committee hearing:

… at a portfolio level the CEFC must still show a positive

return on the Grid Reliability Fund. This is a similar type of obligation that

the CEFC holds for the $10 billion fund where the overall rate of return is

specified at a portfolio level, not at an individual project level. The use of

regulations that is also in the bill to prescribe the additional form of

investment is subject to the normal disallowance procedures of each house of

parliament under the Legislation Act 2003. There's been some misconception that

there's no further control … from parliament over the regulations that the

minister might make under the amendments to the act.[204]

Expanded CEFC functions

Item 5 inserts a new corporate function for the

CEFC:

(ba) at the

request of a responsible Minister, to assist Commonwealth agencies in the

development or implementation of policies or programs relating to supporting

the reliability of energy grids.

This is in addition to the CEFC’s current functions in

section 9 of the CEFC Act, which are its investment function, and to

liaise with relevant persons and bodies, including ARENA, the Clean Energy

Regulator, other Commonwealth agencies and state and territory governments, for

the purposes of facilitating its investment function.[205]

Stakeholder comments

This amendment was not widely commented on by

stakeholders, although the Australia Institute raised concerns that ‘this

appears to be set up to facilitate the UNGI program, bleeding the roles of

Government and independent financing institution’.[206]

Indeed, DISER’s submission to the Committee notes that this amendment:

… will allow the Government to draw upon the CEFC’s expertise

when structuring finance or settling terms and conditions in relation to any

shortlisted UNGI projects not taken on by the CEFC. It will also allow the CEFC

to provide advice to the Government on any of its other initiatives to improve

and support grid reliability.[207]

The Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) considered:

In principle this is an appropriate expansion of the CEFC’s

function and will allow the Government's broader policy suite to include

greater financial sector expertise in how the government policies can be rolled

out.[208]

Establishing

the Grid Reliability Fund

Items 23 to 32 introduce provisions into the CEFC

Act to establish a Grid Reliability Fund and to permit the CEFC to

administer investments under that fund in addition to the existing general CEFC

investment functions.

Item 23 inserts proposed Division 1A—Grid

Reliability Fund Special Account, into Part 5 of the CEFC Act, which

deals with the CEFC’s financial arrangements. Proposed Division 1A consists of proposed

sections 51A to 51E. Proposed section 51A will establish a

GRF Account and proposed section 51B will credit the account with

$1 billion on the day the Act commences.[209]

Proposed section 51C provides that the purpose of

the GRF Account is to make payments to the CEFC as authorised by the Minister. Proposed

sections 51D and 51E provide for the CEFC to request payments, and for the

Minister to provide authorisation for payments to the CEFC.

Section 53 sets out how the CEFC can spend its money. Proposed

subsection 53(2A) provides that GRF money must only be used by the CEFC in

performing its investment function in relation to GRF investments; paying or

discharging the costs, expenses and other obligations of its GRF functions; and

returning surplus money to the Commonwealth under section 54.[210]

Item 32 inserts proposed section 58A to set

out the qualifying criteria for a grid reliability fund investment. As

well as requiring that such an investment must be made for the purposes of the CEFC’s

investment function, the investment must be made to support:

- energy

storage

- electricity

generation, transmission or distribution or

- electricity

grid stabilisation.

Proposed paragraph 58A(c) further requires that a grid

reliability fund investment must meet ‘the criteria (if any) set out in the

Investment Mandate relating to its role in supporting the security or

reliability of the energy system in Australia.’

The Explanatory Memorandum states that ‘(i)t is intended

that the Investment Mandate will provide detailed criteria for what will

constitute supporting the reliability or security of the electricity grid and

what investments should be prioritised.’[211]

In the absence of any additional criteria, the categories

of investment listed under proposed section 58A are quite broad and

appear to include most technologies related to the energy market. For some

discussion of the issues related to leaving detailed qualification criteria to

be set out in a non-disallowable instrument, see the section below.

Key issue—additional Ministerial

powers through the Investment Mandate

As noted above, the new category of GRF investment must

meet criteria set out in the Investment Mandate. The Explanatory Memorandum

states:

It is intended that the Investment Mandate will provide

detailed criteria for what will constitute supporting the reliability or

security of the electricity grid and what investments should be prioritised.[212]

According to DISER, this will be in the form of a separate

GRF Investment Mandate that will be issued following passage of the Bill.[213]

Concerns have been raised that, through the Investment

Mandate, the Minister could direct the CEFC to invest a given proportion of the

GRF in gas powered generation. During the Committee hearing a representative of

DISER addressed this concern, confirming that ‘there is some prospect’ that the

Investment Mandate could ‘have some sense’ of a proportion of funding towards

gas, but noted that the Minister could not direct the CEFC to invest in a

specific gas project.[214]

Some submissions made note of the fact that the Investment

Mandate is a non-disallowable instrument, and expressed concerns that leaving

investment criteria to be defined by the Investment Mandate provides excessive

and inscrutable power to the Minister.[215]

This issue was also raised by the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of

Bills, and addressed by the Minister (see ‘Committee Consideration’ section).

Key

issue—UNGI program

Since its announcement the Government has made it clear

that the GRF is intended to fund eligible shortlisted projects under the UNGI

program.[216]

This intention is reiterated in the Explanatory Memorandum.[217]

However, the CEFC Act provides that the Minister must not give direction

‘that has the purpose, or has or is likely to have the effect, of directly or

indirectly requiring the Board to, or not to, make a particular investment.’[218]

The ACF and other organisations consider the transfer of

pre-selected UNGI projects to the CEFC to impact the CEFC’s independence and

commercial rigour:

Transferring the UNGI program to CEFC is a form of direction,

since there are already 12 short-listed projects. Most (i.e. the five gas

projects and one coal project) would not meet the current CEFC guidelines for

low emissions investment, and they may also be loss making propositions that

CEFC would not otherwise consider.

What is clear is that CEFC has not had the opportunity to

apply its current level of risk management and investment scrutiny to these

projects, the process of choosing them has been extremely opaque and the UNGI

program itself has never been fully defined. While it is possible that some of

the UNGI projects (i.e., the six pumped hydro projects) would be good

candidates for CEFC investment, none of them should be forced on the CEFC.[219]

The Australia Institute has also raised concerns in

regards to the UNGI, noting in its submission:

The legal advice commissioned by the Australia Institute

suggests that Federal Government has no other way of funding the UNGI program,

and specifically the coal-fired power plant upgrade.

…

The GRF media release states that ‘the Government will only

refer UNGI projects that reflect the CEFC’s legislative mandate for

consideration under the Fund’. Given the Bill proposes expanding the

legislative mandate, there is little stopping the CEFC from proceeding with the

UNGI shortlisted coal-fired power plant.[220]

DISER’s submission states:

It will also remain at the CEFC’s discretion which, if any,