Bills Digest No.

53, 2019–20

PDF version [1293KB]

Karen Elphick

Law and Bills Digest Section

November 2019

Contents

Bills Digest at a glance

History of the Bill

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Outline of position of major interest

groups

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Financial implications

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO GENERAL

SENTENCING AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

Revocation of parole

Criminal procedure—evidence of

vulnerable persons

Reasons for granting bail to be

recorded in certain circumstances

Schedule 8, items 1 and 2—Additional

general sentencing factors

Residential treatment orders as a

sentencing option

PROPOSED AMENDMENTS SPECIFICALLY

APPLYING TO CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE OFFENCES

Background

Proposed definitions inserted in the Crimes

Act

Additional child sex abuse offences

and broader application for existing offences

Schedule 5—Increased penalties

Schedule 7, Part 2—Presumption against

bail

Schedule 8—Objective of rehabilitation

must be considered when sentencing child sex abuse offenders

Schedule 9—Additional sentencing

factors—Criminal Code

Schedule 10—Cumulative sentences

Schedule 11— Conditional release of

offenders after conviction

Date introduced: 11 September 2019

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Attorney-General

Commencement: The

formal provisions of the Bill commence on Royal Assent.

The commencement date for each schedule is set out in

this Digest in the discussion of that schedule.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2019.

Bills Digest at a glance

The Crimes Legislation Amendment (Sexual Crimes Against

Children and Community Protection Measures) Bill 2019 (the Bill) passed the

House of Representatives on 15 October 2019. The key measures in the Bill amend

the Crimes Act

1914 and the Criminal

Code Act 1995 (Criminal Code) to:

- increase protections for vulnerable witnesses in relation to

giving evidence, especially through the use of video evidence

- amend the sentencing factors for all federal offenders to provide

that the seriousness of an offence will be aggravated where a person uses their

community standing to facilitate the crime

- emphasise the importance of access to rehabilitation and

treatment when sentencing child sex offenders

- create a new offence of providing electronic services to

facilitate dealings with child abuse material

- create new offences of ‘grooming’ a third party—using the post, a

carriage service or outside Australia—to facilitate sexual activity with a

child

-

increase maximum penalties across the spectrum of child sex

offences

- introduce presumptive minimum sentences for the most serious

child sex offences and for perpetrators convicted of second and subsequent

offences with lower penalties

- introduce a presumption against bail for persons accused of

offences which could result in a minimum sentence of imprisonment and

- introduce presumptions in favour of cumulative sentences and

actual imprisonment for child sex offenders.

Committee reports

The Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee and

the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights expressed concern about provisions

in Schedules 6, 7 and 11 of

the Bill.

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation

Committee published a report recommending that the Senate pass the Bill; however,

Australian Labor Party (Labor) Senators issued a Dissenting Report that

recommended the Bill be amended, including to remove mandatory

minimum sentencing, and that the Government provide appropriate undertakings to

conduct further inquiry. The Australian Greens Senator on the Committee also

issued a Dissenting Report recommending that the Bill be

withdrawn and redrafted without mandatory minimum sentencing, and with

consideration of the technical concerns raised in various legal submissions.

Key Issues

Most interest groups support protections for vulnerable

witnesses and agree that current sentences for child sex abuse offences do not

reflect community expectations.

Interest groups generally support an increased emphasis on

treatment and rehabilitation; however, several questioned the resourcing and

availability of relevant programs.

While several interest groups representing child sexual

abuse survivors expressed support for mandatory minimum sentencing and

presumptions against bail, some preferred alternative measures, and many

interest groups expressed strong opposition to those measures.

History

of the Bill

A substantially similar Bill, the Crimes

Legislation Amendment (Sexual Crimes Against Children and Community Protection

Measures) Bill 2017 (the 2017 Bill), was introduced on 13 September 2017.[1]

The 2017 Bill passed the House of Representatives but lapsed at the end of the

last Senate term on 1 July 2019, after its introduction to the

Senate. A Bills Digest was published for the 2017 Bill.[2]

This Bills Digest uses the research sources of the earlier Digest and repeats

some of the commentary; however, it is a fresh consideration of the Bill.

Purpose of the Bill

The purpose of the Crimes

Legislation Amendment (Sexual Crimes Against Children and Community Protection

Measures) Bill 2019 (the Bill),[3]

is to amend the Crimes

Act 1914 and the Criminal Code Act

1995 (Criminal Code). The purpose of the amendments is described

in the Explanatory Memorandum:

This Bill better protects the community from the dangers of

child sexual abuse by addressing inadequacies in the criminal justice system

that result in outcomes that insufficiently punish, deter or rehabilitate

offenders. The Bill targets all stages of the criminal justice process, from

bail and sentencing through to post‑imprisonment options.

This Bill combats the evolving use of the internet in child

sexual abuse and addresses community concern that the sentencing for child sex

offences is not commensurate to the seriousness of these crimes.[4]

Key measures proposed by the Bill will: [5]

- increase protections for vulnerable witnesses in relation to

giving evidence, especially through the use of video evidence

- amend the sentencing factors for all federal offenders to provide

that the seriousness of an offence will be aggravated where a person uses their

community standing to facilitate the crime

- emphasise the importance of access to rehabilitation and

treatment when sentencing child sex offenders

- create a new offence of providing electronic services to

facilitate dealings with child abuse material

- create new offences of ‘grooming’ a third party—using the post, a

carriage service or outside Australia—to facilitate sexual activity with a

child

- increase maximum penalties across the spectrum of child sex

offences

- introduce presumptive minimum sentences for the most serious

child sex offences and for perpetrators convicted of second and subsequent

offences with lower penalties

- introduce a presumption against bail for persons accused of

offences which could result in a minimum sentence of imprisonment and

- introduce presumptions in favour of cumulative sentences and

actual imprisonment for child sex offenders.

Structure of the Bill

The Bill proposes amendments in 14 schedules which can be

grouped together by purpose as follows:

Amendments of general application to Commonwealth

sentencing and criminal procedure

- Revocation of parole order or licence—Schedules 1 and 13

- Criminal procedure for dealing with vulnerable persons—Schedules

2 and 3

- Courts must provide reasons for bail in certain circumstances—Schedule

7, Part 1

- Additional factors to be taken into account on sentencing—Schedule

8, items 1 and 2

- Residential treatment orders as a sentencing option—Schedule

12.

Amendments relating specifically to child sexual abuse

offences

- Definitions in the Crimes Act—Schedule 14

- New child sex abuse offences in the Criminal Code—Schedule

4

- Sentencing law for child sexual abuse offences

- Increased

penalties—Schedule 5

- Minimum

sentences—Schedule 6

- Presumption

against bail—Schedule 7, Part 2

- Matters

court has regard to when passing sentence—Schedule 8, item 3

- Additional

sentencing factors for certain offences—Schedule 9

- Cumulative

sentences—Schedule 10

- Conditional

release of offenders after conviction—Schedule 11.

Background

Royal Commission into

Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse

The Gillard Labor Government appointed a

six-member Royal Commission to investigate ‘Institutional Responses to Child

Sexual Abuse’ in 2012 (the Royal Commission).[6]

The Royal Commission’s research report, Criminal

Justice, was released on 14

August 2017.[7]

In a summary document, Final Report: Recommendations, the Commission

made 85 recommendations aimed at reforming the Australian criminal justice

system in order to provide a fairer response to victims of institutional child

sexual abuse.[8]

The Australian Institute of Criminology prepared a special

report for the Royal Commission, Historical Review

of Sexual Offence and Child Sexual Abuse Legislation in Australia: 1788–2013.[9]

The report provides information on all sexual offence and child sexual abuse

legislation in Australian jurisdictions and changes in attitudes to sexual

offences and policy over time.

The Bill is consistent with some of the recommendations

made by the Royal Commission; however, the Explanatory Memorandum is not

explicit about which recommendations the Bill is implementing.[10]

Scrutiny of 2017 Bill

The 2017 Bill passed the House but lapsed on 1 July 2019

after its introduction to the Senate.[11]

The Bill was referred to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Legislation Committee which issued a report on 16 October 2017.[12]

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills (the

Scrutiny Committee) reported on the Bill in Scrutiny Digest 12 of 2017

and asked the Minister to provide more information. The Minister’s response and

the Scrutiny Committee’s further comments are published in Scrutiny Digest

13 of 2017.[13]

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR)

considered the 2017 Bill in Human Rights Scrutiny Report 11 of 2017 and

also asked the Minister for more information. The Minister’s response and the

PJCHR’s further comments are in Human Rights Scrutiny Report 13 of 2017.[14]

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Scrutiny Committee considered the Bill on 18 September

2019 in Scrutiny Digest 6 of 2019.[15]

The Scrutiny Committee referred to its comments on the

2017 Bill in Scrutiny Digest 13 of 2017,[16]

and noted it did not have any additional comments regarding:

- procedural fairness and broad discretionary power (Schedule 1,

proposed paragraph 19AU(3)(ba)) and

- reversal of legal burden of proof (Schedule 4, items 20, 22,

40 and 42).

- The Scrutiny Committee made additional comment on the

following matters:

- mandatory minimum sentences (Schedule 6, items 1 and 2)

- right to liberty—presumption against bail (Schedule 7, items

1, 3 and 4) and

- right to liberty—conditional release (Schedule 11, items 1, 2

and 3).

The Scrutiny Committee’s comments are further discussed

below under the relevant schedule. The Scrutiny Committee did not request

further advice from the Minister.

Senate

Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee

On 12 September 2019, the Bill was referred to the Senate Legal

and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee (the LCA Committee) for

inquiry following the recommendation of the Selection of Bills Committee.[17]

Submissions to the inquiry closed on 30 September 2019.[18]

The Bill was debated in the House of Representatives on 15 October 2019, before

the LCA Committee had issued its report.[19]

The LCA Committee published its report (LCA Committee Report) on 7 November

2019 recommending that the Senate pass the Bill.[20]

Australian Labor Party (Labor) Senators issued a

Dissenting Report that recommended the Bill be amended, and that

the Government provide appropriate undertakings to implement the following

recommendations:

- Schedule 6 should be deleted from the bill.[21]

- The bill should be amended to include a

comprehensive statutory review of Commonwealth sentencing practices for child

sex offences. The findings of that review should be reported to the Parliament

within three years of the bill coming into effect.

- The Government should commence an urgent

inquiry into the adequacy of the resourcing that:

- is currently available to

state and territory authorities, including courts, to implement the measures

introduced by this bill; and

- is currently available to

authorities across Australia for the detection and apprehension of those who

commit crimes against children, especially online,

and report to the Parliament within 6 months.[22]

The Australian Greens (the Greens) also issued a

Dissenting Report that recommended that the Bill be withdrawn and

redrafted without mandatory minimum sentencing, and with consideration of the

technical concerns raised in various legal submissions to this inquiry.[23]

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Labor is broadly supportive of many aspects of the Bill.

In debate in the House of Representatives, the Shadow Attorney-General Mark

Dreyfus noted that the LCA Committee had not yet reported on the Bill and

indicated that, out of respect for the process of the Committee and the

organisations and individuals engaging with it, Labor ‘will not finalise its

position on the majority of measures introduced by this bill until that inquiry

has concluded’.[24]

Mr Dreyfus stated:

Labor are committed to doing what we can to protect children

from harm and abuse ... To the extent that there is disagreement between us and

the government on this subject matter, it will only ever be about the means and

not the ends ... there are clearly many aspects of this bill that should enjoy

broad support across this parliament, subject to working through the detail.

The introduction of measures to protect child and other

vulnerable witnesses in court proceedings, the creation of aggravated offences

where a child victim has a mental impairment and requiring judges to consider a

range of additional factors, including aggravating factors, at the time of

sentencing are potential examples.

I would also add that Labor does not, as a matter of

principle, oppose increasing maximum penalties in appropriate circumstances.

Where there is evidence that offenders are consistently being given sentences

that are, on any view, inadequate, it is appropriate for the parliament to

respond by increasing maximum penalties. Doing so sends a clear signal to

judges that sentences should be higher, a signal that as a matter of law and

established sentencing practices cannot be ignored. That is why when a version

of this bill was brought before the previous parliament, Labor called for

amendments to further increase maximum sentences for some child sex offences

over and above the increases originally proposed by the government.

...

Labor opposes mandatory sentencing and detention regimes;

they are often discriminatory in practice, conflict with the role of the

judiciary as an independent arm of government, and have not proved effective in

reducing crime or criminality.[25]

A number of other members of Labor also expressed

opposition to mandatory sentencing during the second reading debate.[26]

A Labor amendment to the second reading motion, which noted

that the Opposition supported the objectives of the Bill and sought to work

with the Government on alternative approaches to sentencing to achieve the

Bill’s objects, did not pass the House.[27]

The Bill passed the House of Representatives without a division.[28]

Senator Nick McKim stated in the Greens Additional

Comments to the Committee inquiry into the 2017 Bill that:

- the Greens were supportive of legislative measures that address

protecting children against sexual abuse and harm

- the Greens have consistently opposed mandatory minimum sentences

- the 2017 Bill should have been shaped by the final reports of the

Royal Commission and the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) inquiry into

Incarceration Rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

- the inclusion of the presumption against bail within the 2017 Bill

was inconsistent with the presumption of innocence

- the presumption in favour of cumulative sentences contained

within the 2017 Bill would lead to unfair and unjust outcomes.[29]

In their Dissenting Report to the Committee inquiry on the

2019 Bill, the Greens stated they considered:

... sexual offences committed against children to be extremely

serious, and believe serious sex offenders should receive appropriate sentences

that are, ... in line with increasing societal understanding of the seriousness

of [sexual crimes against children] and the enduring impact of such offences on

survivors.[30]

The Greens recommended that the Bill be

withdrawn and redrafted without mandatory minimum sentencing, and with

consideration of the technical concerns raised in various legal submissions to

this inquiry.[31]

The Greens did not speak during the second reading debate

in the House of Representatives.[32]

Outline of position of major

interest groups

Twenty two submissions by interest groups were made to the

LCA Committee inquiry into the Bill.[33]

This section contains only a summary of the positon of major interest groups.

Their positions are discussed further under the relevant schedule.

Bravehearts

Bravehearts is an agency that works with and advocates for

survivors of child sexual harm. It broadly supports the proposed amendments as

promoting justice for survivors. Bravehearts additionally advocates for minimum

standard non-parole periods (NPP) as preferable to the proposed amendments

setting mandatory minimum sentences with the minimum NPP set by the court. The

effect would be to legislatively impose a minimum time served in custody rather

than a minimum head sentence.[34]

Knowmore

Knowmore is a nation-wide free legal service for victims

and survivors of child abuse. Knowmore is generally supportive of the Bill’s

objects, however, is concerned that some of the proposed amendments depart from

the findings and recommendations of the Royal Commission. In particular

Knowmore advocated for the Bill to introduce further amendments to Part IAD of

the Crimes Act to include adult victims and survivors of child sexual

abuse within the definition of ‘vulnerable adult complainant’.[35]

Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Psychiatrists

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of

Psychiatrists (RANZCP) is the principal organisation representing the medical

specialty of psychiatry in Australia and New Zealand and is responsible for

training, educating and representing psychiatrists on policy issues.[36]

The RANZCP broadly supports the amendments as reflecting

community expectations and responding to emerging trends. The RANZCP supports

the Bill’s focus on community safety, especially the addition of community

safety as a factor in granting bail, and the presumption against bail.[37]

The RANZCP stated: ‘[r]esearch has demonstrated that

treatment can reduce rates of recidivism in sexual offenders’.[38]

The RANZCP believes that the requirement for the courts to consider

rehabilitation when sentencing an offender, and the courts’ ability to impose

treatment conditions, is an important balance to increased maximum penalties

and mandatory sentencing:

The RANZCP is pleased to see that the Bill distinguishes the sentencing

and rehabilitation options for intellectually disabled offenders from offenders

more broadly, acknowledging that options may need to be modified to be

effective for that population.[39]

Sexual Assault Support Service

Sexual Assault Support Service (SASS) provides free and

confidential counselling, crisis support, case management and advocacy for

people of all ages who have been affected by any form of sexual violence. SASS also

provides counselling to children and young people who are displaying problem

sexual behaviour or sexually abusive behaviour, along with support and information

for their family members and/or carers, and delivers a Redress Scheme Support

Service to survivors of institutional child sexual abuse.[40]

SASS broadly supports the measures proposed in the Bill;

however, SASS does not support mandatory minimum sentencing on the basis that

there is not sufficient evidence to suggest it is an effective response. SASS

would prefer to see presumptive minimum NPPs and guideline judgments.[41]

Carly Ryan Foundation

The Carly Ryan Foundation is a not-for-profit, registered

harm prevention charity created to promote internet safety and prevent crime

against children under the age of 18 years.

The Carly Ryan Foundation broadly supports the proposed

amendments, including the proposed offences, however expressed concern that

courts retain the capacity to set low minimum NPP.[42]

Justice Action

Justice Action works to defend and advocate for those

detained in Australian prisons and hospitals. It supports individualised

justice in criminal trials. Justice Action did not support the amendments

proposed in the Bill on the basis that:

- general deterrence is a discredited sentencing principle[43]

- imposing harsh and mandatory penalties undermines the sentencing

principle of proportionality

- a better approach is to increase resources directed to

rehabilitation programs

- harsh sentences make children less likely to report abuse by

close family members[44]

Justice Action advocated for the creation of a specialist

Sexual Offences Court.[45]

Submissions from legal

representative bodies

The Law Council of Australia (Law Council)

supported the broad policy intent of the Bill but raised concerns about several

provisions.[46]

The Law Council was particularly concerned:

- that the mandatory minimum sentencing provisions may apply to

conduct between teenagers using the internet

- that the Bill would place additional strain on the criminal

justice system without committing additional resources

- the presumption against bail is ‘inconsistent with the presumption

of innocence and established criminal law principles’ and

- the presumption in favour of cumulative sentences, and

presumption in favour of an actual sentence being served may result in unjust

outcomes.

The Law Council recommended the Bill should not be passed

in its current form.[47]

Legal Aid NSW expressed a number of concerns with

the drafting of the Bill, particularly in relation to increases in sentences

and hampering of judicial discretion.[48]

Legal Aid Western Australia did not support several

of the proposed amendments including those relating to mandatory sentencing,

presumption against bail and cumulative sentencing.[49]

Shine Lawyers have extensive experience

representing survivors of abuse in plaintiff litigation and seeking redress

from every institutional redress scheme in Australia.[50]

They note:

Our clients often express difficulty in coming to terms with

what they feel are inadequate sentences for perpetrators of child sexual abuse.

As a general proposition we agree tougher penalties ought to be imposed and the

increased sentences in Schedule 5 of the bill are one such way.

We do not, however, support the implementation of mandatory

minimum sentences for child sexual abuse offenders. Our view is that imposing

mandatory minimum sentences is unlikely to deter offenders.[51]

The Australian Lawyers Alliance (ALA) is a national

association of lawyers, academics and other professionals dedicated to

protecting and promoting justice, freedom and the rights of the individual.[52]

The ALA commented solely on the mandatory sentencing provisions in Schedule 6

and strongly opposed both the provisions themselves and the ‘associated

implication (which is false in our experience) that it is necessary because of

judicial incompetence’.[53]

Statement

of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[54]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR)

considered the Bill on 17 September 2019 in Human Rights Scrutiny

Report 5 of 2019.[55]

The PJCHR reiterated its views as set out in its previous reports on the 2017

Bill.[56]

The PJCHR did not request further advice from the Minister. In Human Rights

Scrutiny Report 13 of 2017, the PJCHR expressed concerns with respect to

several provisions.

Mandatory

minimum sentencing provisions in Schedule 6

The PJCHR found there is a risk that the mandatory minimum

sentencing provisions in Schedule 6 of the Bill may operate in ‘individual

cases in a manner which is incompatible with the right to liberty and the right

to be free from arbitrary detention’ because:[57]

- some sentencing discretion is retained by the court as they are

able to set the minimum NPP, however it is ‘significantly limited’

- the grant of parole after a prisoner has served the minimum

sentence is a matter of discretion

- although the court can apply certain discounts ‘it is unclear

that the courts will be able to take fully into account the particular

circumstances of the offence and the offender in determining an appropriate

sentence’.[58]

The

presumption against bail in Schedule 7

The PJCHR found the presumption against bail in Schedule

7 of the Bill poses a risk that, if the threshold for displacing the

rebuttable presumption against bail is too high, it may result in loss of

liberty in circumstances that may be incompatible with the right to release

pending trial:

... a rebuttable presumption against bail remains a serious

limitation on the right to release pending trial. International

jurisprudence indicates that pre-trial detention should remain the exception

and that bail should be granted except in circumstances where the likelihood

exists that, for example, the accused would abscond, tamper with evidence,

influence witnesses or flee from the jurisdiction.[59]

Conditional

release of offenders after conviction in Schedule 11

The PJCHR found that the threshold of 'exceptional

circumstances' appears intended to operate as a significant hurdle to

sentencing a person to a suspended sentence rather than imprisonment in

custody. Whether this is a sufficient safeguard against the risk of arbitrary

detention will depend on how 'exceptional circumstances' are interpreted by the

courts.[60]

The PJCHR found that there is some degree of risk that the

measure could operate so as to be incompatible with the right to liberty if

incarceration is not reasonable, necessary and proportionate in all the

circumstances of the individual case.[61]

Financial implications

The Government does not expect any additional financial

cost to the Commonwealth. The Explanatory Memorandum notes: ‘[t]here will be

some increase in costs borne by state and Commonwealth agencies for

investigating and prosecuting new offences, and these costs will be absorbed’.[62]

The Explanatory Memorandum does not identify any costs

associated with proposed requirements that courts:

- specifically consider whether it is appropriate to make orders

that include conditions relating to rehabilitation or treatment options and whether

the custodial period provides sufficient time for the offender to undertake

rehabilitation, noting that programs are available both in custody and in the

community (Schedule 8)

- of summary jurisdiction keep a record of reasons for granting

bail in respect of certain serious offences and child sex abuse offences as

required by Schedule 7 and

- only order release of child sex offenders after serving a term of

imprisonment and on a recognizance release order subject to the supervision of

a parole officer as required by Schedule 11.

‘Negligible’ higher costs for

states and territories

The Government flags that the Bill may result in higher

costs for the states and territories due to a small rise in the number of

federal offenders incarcerated in state and territory prisons but observes:

Convicted federal offenders comprise approximately 3 percent

of Australia’s total prison population while convicted federal sex offenders

comprise approximately 0.4 percent of that population. As such, the overall

financial impact on states and territories will be negligible.[63]

The predicted number of prisoners involved and the

anticipated cost is not provided in the Explanatory Memorandum.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reports that during

the June quarter 2019, the average daily number of federal sentenced prisoners

in Australia was 854. Over three quarters of the federal sentenced prisoners in

the June quarter 2019 were held in New South Wales (NSW) (49 per cent or

417 persons) and Victoria (27 per cent or 228 persons).[64]

If the Explanatory Memorandum is correct, NSW would hold, on average,

approximately two federal sex offenders at any one time.

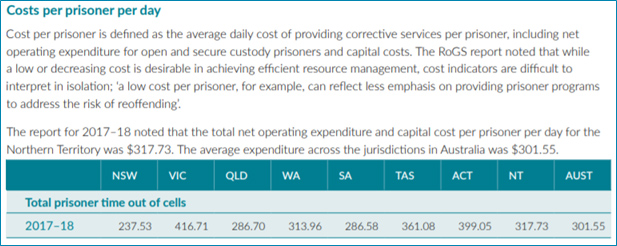

The Department of the Attorney-General and Justice (NT)

provided comparative figures for the cost of prisoners per day in the different

jurisdictions in its Annual Report reproduced at Figure 1

below.[65]

The data comes from the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services

(RoGS): ROGs most recent confirmed statistics are for 2017–18.[66]

The average expenditure across the jurisdictions in Australia was $301.55. The

lowest expenditure was in NSW at $237.53.

Figure 1: cost per prisoner per

day across Australia

Source: Northern Territory, Department of the Attorney-General and Justice (DAGJ), Annual

report 2018–19, DAGJ, 2019, p. 39.

Example of impact of increased

penalties—subsection 474.27(1) of the Criminal Code

Sentencing statistics for the offence of grooming a child

using a carriage service (subsection 474.27(1) of the Criminal Code)

between 1 February 2014 to 31 January 2019 were supplied by the Attorney-General’s

Department (AGD) and the Department of Home Affairs (DHA):[67]

- 80 convictions were recorded, with 44 sentences of imprisonment

handed down

- 12 offenders were sentenced to community service and one was

released on a non-conviction order; 23 offenders were released on recognizance

release orders (RRO) without spending any time in prison

- the longest head sentence was 3.5 years imprisonment and the

lowest two months; the most frequent head sentence was 18 months imprisonment.[68]

It is not clear how many offenders were involved; however,

if each recorded sentence of imprisonment was for a discrete offender, 44

offenders over a five year period spent at least some time in prison for this

offence. For the calculations below the time actually served is estimated

conservatively at 50 per cent of the head sentence.

Assume that 60 percent of those 44 offenders (26

offenders) had 18 month sentences, two offenders had a 3.5 year sentence and

the remainder (16 offenders) averaged four months; the total cost of

imprisonment in NSW (the cheapest jurisdiction) would be: ((26x365 daysx1.5

years)+(2x365 daysx3.5 years)+(16x120 days))x50% time served=9,355 prisoner

daysx$237.53 per day at a cost of $2.2 million over five years.

Schedule 5 would increase the maximum penalty for

an offence against subsection 474.27(1) of the Criminal Code from 12

years to 15 years imprisonment (an increase of 25 per cent). No minimum

sentence is proposed by the Bill for an offence against subsection 474.27(1) of

the Criminal Code for first offenders; however the minimum sentence

under proposed section 16AAB for a second or subsequent offence is four

years imprisonment.

It is not possible to accurately assess from the

statistics provided the increase in number of days served and therefore the

increased cost. However, for the sake of comparison, a conservative estimate

can be provided. Using the same offender numbers as above, assume that:

- the two longest sentences were for second offences and those

offenders were given the mandatory minimum four year sentences

- the 26 offenders with 18 month sentences had their head sentence

increased to 2.5 years as a result of the signal to increase sentences given in

Schedule 5 and the requirement to consider longer non-parole periods to access

rehabilitation and treatment options

- the average sentence for the remaining 16 offenders increased by

25 per cent to five months.

Now the calculation is: ((2x365 daysx4 years)+(26x365

daysx2.5 years)+(16x150 days))x50% time served=14,522.5 prisoner daysx$237.53

per day at a cost of $3.4 million over five years.

The amendments in Schedule 13 intended to ensure an

offender whose parole or licence is revoked would spend some time in custody

are also likely to increase total prisoner days. For the above prisoner cohort,

at least 67 of the offenders would spend time on an RRO, parole or release on

licence.

Even with a small prisoner cohort, and these estimates are

for only one offence, presumptive minimum sentences and increased penalties are

capable of rapidly driving up prison populations and costs. The Explanatory

Memorandum does not indicate whether the Government has consulted with the

states and territories on the effects of the proposed amendments.

Prison

overcrowding across Australia

As a result of rising rates of imprisonment there is a

significant jail overcrowding problem in every state and territory in

Australia.[69]

As at 30 June 2018, Victoria reported that ‘[t]here were 7,666 prisoners in the

Victorian prison system on 30 June 2018. This represents an increase of 81.5

per cent on the 30 June 2008 figure of 4,223.’[70]

The NSW Audit Office described the problem in NSW as

urgent.[71]

It reported in May 2019 that measures being taken to manage overcrowding in NSW

include doubling-up or tripling-up the number of beds in cells, reopening

previously closed facilities and using obsolete facilities. The Audit Office also reported that the

overcrowding is affecting placement of prisoners on programs to address sexual

reoffending:

A lack of sufficient bed capacity in metropolitan area

affects the specialist programs that are offered exclusively within that

region, including for violent and sex offenders ... more than 500 eligible

inmates were on extended waitlists for programs to address sexual reoffending. [72]

Position of major interest

groups

The following interest groups made submission to the LCA

Committee suggesting that additional funding would be required to implement the

requirements of the Bill:

- Legal Aid Western Australia and the Centre for Crime, Law and

Justice at the University of NSW in relation to availability of both custodial

and community rehabilitation[73]

- the Law Council in relation to the increased burden on the courts

and criminal justice system and specifically for the residential treatment

order regime.[74]

PROPOSED

AMENDMENTS TO GENERAL SENTENCING AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

Revocation of parole

Schedule 1—Revocation of parole

order or licence without notice to protect community

Schedule 1 is unchanged from the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 1

Section

19AU of the Crimes Act allows the Attorney-General, under certain

conditions, to revoke a parole order or licence at any time before the end of

the parole or licence period. The Attorney-General must usually give 14 days’

notice of his or her intention to revoke. There are already four exceptions

to the requirement to give notice.

Schedule 1 will insert an additional exception to

allow the Attorney-General to revoke the parole or licence without giving

notice to the person in the interests of ensuring the safety and protection

of the community or of another person.

|

Commencement

Schedule 1 will commence on the day after Royal

Assent.

Explanation of provisions

As part of standard sentencing practices, a court can use

its discretion to determine a non-parole period of the prison sentence, after

which time the offender can usually apply administratively for parole. In

relation to federal sentences of imprisonment, no application is needed—the

Attorney-General is required to consider whether to release a prisoner before

the end of their NPP.[75]

Parole may be allowed with conditions; for example, weekly reporting or limited

movement.

Section 19AU of the Crimes Act allows the

Attorney-General, by written instrument, to revoke a parole order or licence at

any time before the end of the parole or licence period if the person has

failed to comply with a condition of the order or licence, or there are

reasonable grounds for suspecting that the offender has failed to comply.

The general rule is that the Attorney-General must give 14

days written notice to the person advising them of the condition alleged to

have been breached and that the Attorney‑General proposes to revoke the

parole order or licence. This gives the offender an opportunity to provide

written reasons why the order or licence should not be revoked (subsection

19AU(2)).

Subsection 19AU(3) outlines four conditions that remove

the need for notice to be given to the person. In summary they are where the

person’s whereabouts are unknown, where it is urgent, where the

person is outside Australia or where it is necessary in the interests

of the administration of justice.

Schedule 1 will insert proposed paragraph

19AU(3)(ba) to allow the Attorney-General to revoke the parole order or

licence without giving notice to the person in the interests of ensuring the

safety and protection of the community or of another person.

The proposed amendment is broad and its general

application would mean that parole could be revoked without notice by the

Attorney-General for many federal offenders (including terrorist offenders,

drug offenders and trafficking offenders). If parole is revoked, the person will

be immediately detained in custody. The Explanatory Memorandum states:

Importantly, the person is still afforded procedural fairness

as they retain the opportunity under section 19AX of the Crimes Act to make a

written submission to the Attorney-General as to why the parole order should

not be revoked. However, during this time the person will be remanded in

custody, where they cannot cause harm. If, after considering the person’s

submission, the Attorney-General decides to rescind the revocation order, he or

she would be immediately released from prison.[76]

Position of major interest

groups

The Law Council described this amendment as 'objectionable

on procedural fairness grounds' and recommended its removal. AGD and DHA argued

that procedural fairness protections were incorporated. Legal Aid NSW opposed

the provision as unnecessary. SASS supported the provision but also suggested

it did not seem necessary.[77]

Schedule 13—Revocation of parole

order or licence—serving time in custody

Schedule 13 is substantially the same as Schedule 14 of

the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 13

Schedule 13 implements a federal policy for

calculating how much time a federal offender is liable to serve after parole

is revoked, instead of applying state and territory law to federal offenders.

It also removes the option for a court to make an

immediate Recognizance Release Order (RRO) where a person on parole is

sentenced for a new offence committed while on parole.

The amendments are intended to ensure that where a person

on parole is sentenced for a new offence, the Crimes Act will require

the person to serve a period of time in custody. |

Commencement

Schedule 13 will commence 28 days after Royal

Assent.

Key provisions

A parole order or licence will be automatically revoked

under section 19AQ if a person is sentenced to more than three months

imprisonment for a further federal, state or territory offence committed during

the parole period.

Calculation of credit for ‘clean

street time’

When an offender’s parole is revoked, the remainder of the

sentence to be served for the initial offence must be calculated. An offender

obtains some credit for the period of release without reoffending; this period

is referred to as ‘clean street time’. A person on parole or licence who has

their parole revoked is liable to serve the remainder of the outstanding

sentence less any clean street time.

Subsection 19AA(2) of the Crimes Act currently

applies state and territory laws for calculating clean street time to federal

offenders. However, not all states and territories allow credit for clean

street time and some credit clean street time up to the date of sentencing

rather than to the date of offending. According to the Explanatory Memorandum:

The effect of automatic revocation based on the date of

sentencing rather than at the time at which the further offence was committed

has led to offenders receiving credit for time during which they have not been

of good behaviour. Often it is also the case that the offender has no time left

to serve because of the lapse of time between the commission of the offence and

the date of sentencing.[78]

Proposed section 19AQ introduces a federal policy

intended to reduce the amount of clean street time that can be credited by a

court as time served against the outstanding sentence (item 5). Items

1–4 are consequential amendments implementing that policy.

The amendments will require the sentencing court to

determine the revocation time, which will be the time when the new

offence was: committed, most likely to have been committed, or began to be

committed (proposed subsection 19AQ(3)). The amount of the outstanding

sentence an offender is liable to serve after revocation of the parole order or

licence will then be either:

- the entire balance of the outstanding sentence or

- if the court considers it appropriate having regard to the

person’s good behaviour, that period reduced by the period of clean street time;

that is the entire balance of the sentence, less the period from the date of

release to the revocation time (proposed subsection 19AQ(4)).

Fixing non-parole period where

parole or licence automatically revoked

Section 19AR currently deals with fixing of non-parole

periods where a parole or licence is automatically revoked. Items 6-14

will amend section 19AR to require that a federal offender must usually serve a

period of time in custody where a parole or licence is automatically revoked.

Proposed subsection 19AR(1) applies to a person who

is sentenced to a term of imprisonment for a federal offence that was committed

when the person was on parole or licence for a previous federal offence (item

7). Proposed subsection 19AR(3) deals with situations where a person

is sentenced to a term of imprisonment for a state or territory offence that

was committed when the person was on parole or licence for a previous federal

offence (item 8). In each situation the sentencing court must not make a

recognizance release order and:

- if the person has been sentenced for a new federal offence,

must fix a single new non-parole period for the new sentence and the

outstanding sentence having regard to the total period of imprisonment the

person is liable to serve or

- if the person has been sentenced for a state or territory offence,

must fix a single new non-parole period for the outstanding sentence having

regard to the total period of imprisonment the person is liable to serve.

Exceptions to requirement to serve

a term of imprisonment

Proposed subsection 19AR(4) provides that a court

may decline to fix a non-parole period if the court is satisfied that doing so

is appropriate having regard to:

- the serious nature and circumstances of the offence or offences

and

- the antecedents of the person.

The amendments are subtle: proposed subsection 19AR(4) requires

the court to consider whether it is appropriate to decline to fix a

non-parole period rather than whether it is not appropriate to fix a

non-parole period. The court is also directed to the ‘serious’ nature and circumstances

of the offence’ rather than only the nature and circumstances of the offence.

Proposed paragraph 19AR(4)(b) adds a further

exception that a court may decline to fix a non-parole period if the person is

expected to be serving a state or territory sentence on the day after the end

of the federal sentence.

Criminal procedure—evidence of vulnerable persons

Schedule 2—Use of video

recordings

Schedule 2 is unchanged from the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 2

Items 1 and 2 of Schedule 2 will amend

section 15YM of the Crimes Act to allow a video recording of an

interview of a vulnerable person (a child witness, a vulnerable adult

complainant, or a person declared as a special witness under

section 15YAB, to be admitted as evidence in chief if the interview was

conducted by a constable or a person specified in the regulations.

|

Commencement

Schedule 2 will commence on the day after Royal

Assent.

Explanation of provision

The present position on the admission of pre-recorded

video evidence in criminal proceedings is that a court may grant leave

for a video recording of an interview conducted by police to be admitted as

evidence in chief (paragraph 15YM(1)(b) Crimes Act). Subsection 15YM(2)

prohibits the court from giving leave if satisfied that it is not in the

interest of justice for the person’s evidence in chief to be given by a video

recording.

The Government is concerned that the need to seek leave

for video evidence to be admitted ‘may have an adverse effect on the vulnerable

witness and is contrary to the intent of the vulnerable witness protections

more broadly’.[79]

In his second reading speech, the Attorney-General Christian Porter stated the

amendments would

... improve justice outcomes by limiting the re-traumatisation

of vulnerable witnesses by removing barriers to the admission of pre-recorded

video evidence and ensuring that they are not subject to cross examination at

committal and other preliminary hearings, thus allowing them to put their best

evidence forward at trial.[80]

Item 1 will amend section 15YM to allow a video

recording of an interview of a person (a child witness, a vulnerable adult

complainant, or a person declared as a special witness[81]

under subsection 15YAB(1)), in a proceeding to be admitted as evidence in

chief if a constable, or a person of a kind specified in the regulations,

conducted the interview.

Item 2 will repeal subsections 15YM(2)–(3). This

will remove a requirement in subsection 15YM(2) that a court must not give

leave if satisfied ‘that it is not in the interest of justice for the person’s

evidence in chief to be given by a video recording’. This provision is no

longer needed as the leave of the court will not be required. However, proposed

amendments maintain subsection 15YM(4) which provides that a person must be

available for cross-examination and re-examination if he or she gives evidence

in chief by a video recording.

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that removing the

requirement to seek leave ‘also brings the Commonwealth’s vulnerable witness

protections into line with the approach taken by states and territories’.[82]

The proposed amendments complement recommendations that

were made about police investigative interviewing in relation to reports of

child sexual abuse by the Royal Commission, which stated that police conduct

should accord with principles including:

The importance of video recorded interviews for children and

other vulnerable witnesses should be recognised, as these interviews usually

form all, or most, of the complainant’s and other relevant witnesses’ evidence

in chief in any prosecution.[83]

Position of major interest

groups

The Law Council noted that the removal of the requirement for

leave was best practice, but suggested training for the making and use of

pre-recorded testimony would be needed. Legal Aid NSW supported Schedule 2.[84]

Knowmore was concerned that the proposed provisions do not

fully implement the special measures recommended by the Royal Commission

relating to the prerecording and recording of the evidence of victims and

survivors:

Consistent with the views of the Royal Commission, these

measures should be made available for all complainants in child sexual abuse

proceedings, including adults in proceedings involving historical allegations

of child sexual abuse.

Currently, section 15YM(1A) limits the application of the

special measure to a child witness for a child proceeding; a vulnerable adult

complainant in a vulnerable adult proceeding; and a special witness for whom an

order is in force. As a result of the operation of sections 15Y(2) and 15YAA,

an adult complainant in a proceeding involving historical allegations of child

sexual abuse is not considered to be a vulnerable adult complainant under Part

IAD of the Act. Therefore, they are not eligible for this special measure, and

will not benefit from the use of video recordings unless a court makes specific

orders under the special witness provisions.[85]

Schedule 3—Cross-examination of

vulnerable persons at committal proceedings

Schedule 3 is unchanged from the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 3

Proposed subsection 15YHA(1) of the Crimes Act

prevents the cross-examination, at committal proceedings or proceedings of a

similar kind, of a child witness, a vulnerable adult complainant or a person

declared as a special witness under section 15YAB.

|

Commencement

Schedule 3 will commence 28 days after Royal

Assent.

Background

In its 2006 report, Uniform Evidence Law, the ALRC

found that child witnesses are particularly vulnerable in the adversarial trial

system. In their inquiry into children and the legal process, the ALRC and the

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (now the Human Rights Commission)

‘heard significant and distressing evidence that child witnesses, particularly

in child sexual assault cases, are often berated and harassed to the point of

breakdown during cross-examination’.[86]

Key provisions

Proposed subsection 15YHA(1) of the Crimes Act

prevents the cross-examination, at committal proceedings or proceedings of a

similar kind, of a child witness, a vulnerable adult complainant or a person

declared as a special witness under section 15YAB (item 5). Under

section 15YAB a court may declare a person to be a special witness in relation

to the proceeding if satisfied that the person is unlikely to be able to

satisfactorily give evidence in the ordinary manner because of a disability or intimidation,

distress or emotional trauma.

The Explanatory Memorandum outlines that the amendments in

Schedule 3 will achieve three things:

- vulnerable witnesses will be spared an additional risk of

re-traumatisation

- criminal justice processes will be streamlined by ensuring

lengthy cross-examination is reserved for trials and not committal proceedings

(or proceedings of a similar kind)

- the Commonwealth will be brought broadly into line with practice

in other Australian states and territories.[87]

Position of major interest

groups

Legal Aid NSW opposed the breadth of Schedule 3 and

submitted it should be predominantly targeted toward the sexual offences listed

in section 15Y of the Crimes Act. [88]

Shine Lawyers submitted:

... a rebuttable presumption against cross examination at a

committal hearing would be more flexible than banning cross examination. This

would allow judicial discretion to permit or prevent cross examination of a

vulnerable witness in committal proceedings where proper to do so rather than

imposing a blanket ban.[89]

The Law Council recommended:

The proposed ban on cross-examination of vulnerable witnesses

should be removed from the Bill and replaced by an approach which prevents

cross-examination of vulnerable witnesses unless 'exceptional circumstances'

can be demonstrated and for a defined set of offences only.[90]

AGD and DHA stated that the Bill did not propose a

complete ban on the appearance of vulnerable witnesses at committal hearings

and that the proposed amendments were valuable to prevent re-traumatisation of

vulnerable witnesses.[91]

Reasons for granting bail to be

recorded in certain circumstances

Schedule 7 Part 1—Court records

Schedule 7 Part 1 is in substantially the same terms as

the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 7 Part 1

When a person is charged with one of the serious offences

listed in section 15AA of the Crimes Act, a court is not to grant bail

unless exceptional circumstances exist. Proposed subsection 15AA(3AAA)

requires a court which grants bail to a person under subsection 15AA(1) to

state reasons and keep a record of the reasons.

|

Commencement

Part 1, Division 1 of Schedule 7 will commence on

the day after Royal Assent.

Part 1, Division 2 of Schedule 7 will commence on

the later of:

- immediately after the commencement of the provisions in Part 1,

Division 1 of Schedule 7 (the day after Royal Assent) and

- the commencement of Schedule 1 to the Counter-Terrorism

Legislation Amendment (2019 Measures No. 1) Act 2019.[92]

However, the provisions do not commence at all if the

event mentioned in paragraph (b) does not occur.

Key issue—the purpose of the

provision is not clear

When a person is charged with a Commonwealth offence,

section 15 of the Crimes Act allows a court of summary jurisdiction

to defer the hearing and either remand the defendant to custody until the

hearing, or order bail on condition to appear at the hearing.

Subsection 15AA(1) provides that a bail authority is not

to grant bail to a person charged with, or convicted of, an offence covered by

subsection 15AA(2) unless exceptional circumstances exist to justify bail.

Subsection 15AA(2) covers a range of serious offences such as terrorism

offences.

Item 1 inserts a requirement in proposed

subsection 15AA(3AAA) that if a court grants bail to a person under

subsection 15AA(1), the court must state its reasons and the reasons must be

entered in the court’s records.

The Explanatory Memorandum states that the giving of

reasons is important due to the seriousness of the offences and the potential

risk to the community if bail is granted. It is not clear how the court giving

reasons for granting bail would ameliorate any potential risk to the community.

The outcome of bail applications for serious offences is usually publicly

reported by journalists, especially unusual offences such as terrorism and

espionage. The prosecuting authority is present in court to hear and record the

order.

The Explanatory Memorandum does not indicate how the

additional administrative step would assist community safety.

Schedule 8, items 1 and 2—Additional general sentencing

factors

Schedule 8 is the same as the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 8, Items 1 and 2

Items 1 and 2 require a sentencing court to take into

account when sentencing:

- in addition to a guilty plea, the timing of that guilty plea

and the degree to which the plea resulted in any benefit to the community, or

to any victim or witness and

- whether a person’s professional or community standing has been

used to aid in the commission of an offence.

|

Commencement

Schedule 8 will commence 28 days after Royal

Assent.

Additional sentencing factors

Section 16A of the Crimes Act requires a court, in

determining a sentence to be passed for a federal offence, to impose a sentence

or make an order that is ‘of a severity appropriate in all the circumstances of

the offence’. Subsection 16A(2) outlines the matters to which a court is to

have regard when passing a sentence for a federal offence. The list of matters

includes:

- the nature and circumstances of the offence

- the personal circumstances of any victim of the offence

- the degree to which the offender has cooperated with law

enforcement and

- the need to ensure that the person is adequately punished.

Item 1 amends paragraph 16A(2)(g) which requires

the court to take into account a guilty plea when determining the severity of

sentence appropriate in the circumstances. Proposed paragraph 16A(2)(g)

will also require the court to consider: the timing of that guilty plea, and

the degree to which the plea resulted in any benefit to the community, or to

any victim or witness to the offence.

Item 2 inserts proposed paragraph 16A(2)(ma)

which provides that where a person’s professional or community standing has

been used to aid commission of an offence, that will be an aggravating factor

which might increase the sentence.

The Explanatory Memorandum states the intention of proposed

paragraph 16A(2)(ma):

It is intended that this will capture scenarios where a

person’s professional or community standing is used as an opportunity for the

offender to sexually abuse children. For example, this would cover a medical

professional using their professional standing as a medical practitioner, or a

person using celebrity status, to create opportunities to sexually abuse

children.[93]

The provisions as currently drafted apply to all

Commonwealth offences and are not restricted to Commonwealth child sex

abuse offences.

Residential treatment orders as

a sentencing option

Schedule 12—Additional

sentencing alternatives

Schedule 12 is unchanged from the 2017 Bill.

|

Quick Guide to Schedule 12

Schedule 12 updates the list of alternative

sentencing orders in the Crimes Act to allow Victorian courts to use

Victoria’s new residential treatment orders for federal offenders. The

provisions will also pick up any similar orders that are created by other

jurisdictions.

|

Commencement

Schedule 12 will commence on the day after Royal

Assent.

Residential treatment orders

Subsection 20AB(1) of the Crimes Act allows state

and territory courts to impose on federal offenders any of the alternative

non-custodial sentencing options that are available under the law of that state

or territory and listed in subsection 20AB(1AA). These options currently

include:

- a community correction order

- a drug or alcohol treatment order or rehabilitation order

- a good behaviour order

- an intensive supervision order

- a sentence of weekend detention or a weekend detention order.

Item 1 of Schedule 12 will add a residential

treatment order to the list at proposed subparagraph 20AB(1AA)(a)(viia).

The new order is proposed so that courts in Victoria can apply to federal

offenders the new orders available in Victoria under section 82AA of the Sentencing

Act 1991 (Vic).[94]

Detention of persons with mental illness or intellectual disability

The proposed residential treatment order is not, on the

face of section 20AB, limited in its application to particular offenders;

however, a court can only make such an order if it is empowered to make the

order under a state or territory law, which means that all the conditions that

apply to its use in relation to a state offender automatically apply to a

federal offender.

The Victorian order under section 82AA of the Sentencing

Act 1991 (Vic) is available only for offenders with an intellectual

disability. It allows a sentencing court to order that an intellectually

disabled offender be detained and treated for a period of up to five years if

the offender has been convicted of a ‘serious offence’ (including murder

and kidnapping) or a specified sexual assault offence.[95]

There is already a different type of federal order

available to the court for a person who is suffering from a mental illness or

intellectual disability and is charged with a federal offence.

Under section 20BQ of the Crimes Act, a court of

summary jurisdiction (that is, a local or magistrates court or equivalent) may:

- dismiss the charge and discharge the offender

- unconditionally

or

- into

the care of a responsible person for a maximum of three years (either

unconditionally or subject to conditions) or

- on

condition that the offender attend a certain place or person for assessment

and/or treatment for a maximum period of three years or

- do one or more of:

- adjourn

the proceedings

- remand

the person on bail

- make

any other order.

Where a court makes such an order:

- the order acts as a stay on further proceedings against the

person for that offence and

- the court may not also make certain other types of orders—item

2 of Schedule 12 excludes the proposed paragraph (viia)

residential treatment order from that list of orders.

The effect is that the court will be able to make an order

allowed under state or territory law via subparagraph 20AB(1AA)(a)(viiia) and

an order under section 20BQ of the Crimes Act.

Key differences between the two

orders

Note that the federal section 20BQ orders do not require a

conviction or any particular finding of fact before the court imposes the

order. Federal orders are only available for three years, whereas the Victorian

orders may be for a period of five years.

Interest group comment

The RANZCP is pleased to see that the Bill distinguishes the sentencing

and rehabilitation options for intellectually disabled offenders from offenders

more broadly, acknowledging that options may need to be modified to be

effective for that population.[96]

PROPOSED

AMENDMENTS SPECIFICALLY APPLYING TO CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE OFFENCES

Background

The amendments relating to child sex abuse offences

include proposals for new offences and increased penalties. This section

provides background on Parliament’s power to legislate those proposals and, to

assist Parliament in deciding the appropriate penalties, outlines how the

offences affect children, who commits these offences, and what sentencing

approaches might most effectively prevent reoffending.

Constitutional power to enact

laws relating to child sex abuse

The Australian Constitution leaves the general

legislative power with respect to criminal law with the states and territories.

The Commonwealth has legislative power to make criminal offences related to

subjects within federal legislative power.[97]

So, for example, the Commonwealth has power to make laws with respect to

‘postal, telegraphic, telephonic and other like services’ under section 51(v)

of the Constitution

and with respect to ‘external affairs’ under section 51(xxix).[98]

Constitutional power to impose

mandatory sentences

It is settled law that Parliament has the power to alter

sentencing principles, and can set mandatory minimum sentences and even a

mandatory sentence. In Palling v Corfield, Barwick CJ said that, although

mandatory sentences are undesirable, the court must obey a mandatory penalty

assuming it is valid in other respects:

It is both unusual and in general, in my opinion, undesirable

that the court should not have a discretion in the imposition of penalties and

sentences, for circumstances alter cases and it is a traditional function of a

court of justice to endeavour to make the punishment appropriate to the

circumstances as well as to the nature of the crime. But whether or not such a

discretion shall be given to the court in relation to a statutory offence is

for the decision of the Parliament. It cannot be denied that there are

circumstances which may warrant the imposition on the court of a duty to impose

specific punishment... It is not, in my opinion, a breach of the Constitution not

to confide any discretion to the court as to the penalty to be imposed.[99]

In Magaming v The Queen[100]

the majority of the High Court upheld the mandatory minimum sentences in sections

233C and 236B of the Migration

Act 1958 (Cth) despite an unusual comment in the lower court judgment

of the NSW Court of Appeal that the offender in this case, ‘an illiterate and

indigent deckhand ... pondering his incarceration for five years for a first

offence, could legitimately conclude that, at a human level, he or she had been

treated arbitrarily or grossly disproportionately or cruelly.’[101]

Justice Gageler gave a persuasive dissenting judgment and it is an argument

that may be brought back to the High Court in the future.[102]

Understanding child sex abuse

offending

The harm done by child sex abuse

offending

Volume 3 of the Final Report of the Royal

Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse dealt with the

impact of child sex abuse on victims:

‘As a victim, I can tell you the memories, sense of guilt,

shame and anger live with you every day. It destroys your faith in people, your

will to achieve, to love, and one’s ability to cope with normal everyday living’.

...

The impacts of child sexual abuse are different for each

victim. For many victims, the abuse can have profound and lasting impacts. They

experience deep, complex trauma, which can pervade all aspects of their lives,

and cause a range of effects across their lifespans. Other victims do not

perceive themselves to be profoundly harmed by the experience. [103]

...

Child sexual abuse can affect many areas of a person’s life,

including their:

- mental health

- interpersonal relationships

- physical health

- sexual identity, gender identity and sexual behaviour

- connection to culture

- spirituality and religious involvement

- interactions with society

- education, employment and economic security.

For some victims, child sexual abuse results in them taking

their own lives ... Of the survivors who provided information in private sessions

about the impacts of being sexually abused, 94.9 per cent told us about mental

health impacts. These impacts included depression, anxiety and post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD); other symptoms of mental distress such as nightmares

and sleeping difficulties; and emotional issues such as feelings of shame,

guilt and low self-esteem.[104]

After mental health, relationship difficulties were the

impacts most frequently raised by survivors in private sessions, including

difficulties with trust and intimacy, lack of confidence with parenting, and

relationship problems. Education and economic impacts were also frequently

raised.[105]

The nature of child sex abuse

Volume 2 of the Final Report of the Royal

Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse dealt with the

nature and cause of child sexual abuse.

The Royal Commission found:

Adult perpetrators may use a wide range of tactics and

strategies – including grooming, coercion and entrapment – to enable,

facilitate and conceal the sexual abuse of a child. Grooming can take place in

person and online, and is often difficult to identify and define. This is

because the behaviours involved are not necessarily explicitly sexual, directly

abusive or criminal in themselves, and may only be recognised in hindsight.

Indeed, some grooming behaviours are consistent with behaviours or activities

in non-abusive relationships, and can even include overtly desirable social

behaviours, distinguished only by the motivation of the perpetrator.

Perpetrators can groom children, other people in children’s lives, and

institutions.

Not all child sexual abuse involves grooming. Perpetrators

may also use physical force or violence as a tactic to overcome a child’s

resistance to sexual abuse. This may include coercion, threats and punishment.

This instils fear to enable or facilitate child sexual abuse and silence the

victim.

Child sexual abuse is often accompanied by other forms of

maltreatment, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. Survivors

often told us that they experienced multiple forms of abuse at the same time.[106]

No typical perpetrator

The Royal Commission found:

Despite commonly held misconceptions and persistent

stereotypes, there is no typical profile of an adult perpetrator. People who

sexually abuse children have diverse motivations and behaviours that can change

over time.[107]

Justice Action provided the LCA Committee with a paper

examining the characteristics of sex offenders in detail and which sourced much

of its information from the work of Dr Karen Gelb.[108]

They wished to emphasise:

... it is important for policy makers and community members

alike to realise that not all sexual offending— particularly that committed

within the family—is perpetrated by adults.[109]

Young people are the offenders in a significant number of known

child sexual abuse cases.[110]

In Young People Who Sexually Abuse: Key Issues, Cameron Boyd and Leah

Bromfield of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, observed:

It is unclear how much sexual abuse young people commit. It

is notoriously difficult to accurately measure the rates of sexual abuse of any

kind (Neame & Heenan, 2003). Most official figures are likely to be

underestimates ... Police statistics showing the

percentage of all sexual abuse committed by young people is relatively

consistent (between 9-16%, ... This is consistent with victim reports on

offenders from New South Wales counselling services ... This illustrates that

young people are the offenders in a significant number of known sexual abuse

cases.[111]

According to Boyd and Bromfield, ‘[t]he age of the

offender does not determine the degree of harm caused to the victim. Intrusive

acts of abuse by a school peer or sibling can be just as frightening and

serious as abuse by an adult’.[112]

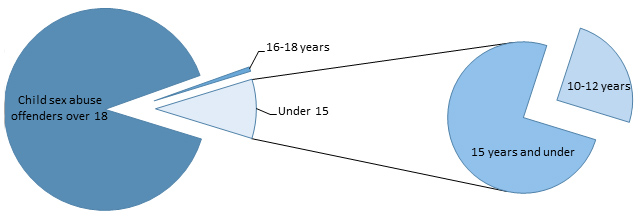

In Australia a child can be held criminally responsible

for their actions at 10 years of age and offenders in the youngest age

group certainly exist. Boyd and Bromfield cite Australian figures suggesting

that 23 per cent of young people who are in treatment for their sexually

abusive behaviours are aged 10–12 years and 70 per cent are 15 years or younger.[113]

The proportions of each group are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: proportion of young

child sex abuse offenders

Source: Parliamentary Library

Juvenile

offenders are different from adult offenders

The Royal Commission explained that children who exhibit

harmful sexual behaviours have often experienced trauma themselves, and require

protection and treatment:

While the sexual harm that children can inflict on other

children should not be minimised, children are not the same as adults in

terms of their sexual and emotional development and legal responsibility.

Children with problematic and harmful sexual behaviours exhibit behaviours that

can range from those that fall outside what is developmentally normal through

to behaviours that are coercive and abusive. Some children, particularly

younger children, may engage in inappropriate sexual interactions without intending

or understanding the harm it causes others.[114]

In their paper Sentencing and reatment of juvenile sex

offenders in Australia, Riddhi Blackley and Lorana Bartels, with the

Australian Institute of Criminology, commented:

Young people with sexually abusive behaviours are likely to

have experienced significant childhood trauma and have often been exposed to

neglect, physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse, had early exposure to sex and

pornography and have often experienced social isolation, as well as disengagement

from school. This does not limit the gravity of their offences.[115]

...

Juvenile offenders are also different from adult offenders in

their neurobiology. Rapid brain development in adolescence affects a youth’s

emotional regulation and response inhibition, making them more prone to taking

risks and particularly susceptible to the influence of peers. These factors

limit an adolescent’s psychosocial maturity, a deficit that has been shown to

contribute to their involvement in crime. Steinberg and Scott (2003) have

argued that psychosocial immaturity restricts a young person’s

decision-making capabilities so much that it may also reduce their criminal

culpability. In addition, young offenders have higher rates of