Bills Digest No. 51, 2019–20

PDF version [1017KB]

Dr Hazel Ferguson, Dr Shannon Clark and Dr James

Haughton

Social Policy Section

14

November 2019

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Background

Committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Policy positions of major interest

groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Key issues and provisions: HELP debt

relief for very remote teachers

Other provisions

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 16

October 2019

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Education

Commencement: Schedules

1 and 2 commence on 1 January 2020. Part 1 of Schedule 3 commences on 1 January 2019.

The remainder of the Bill commences on the day the Act receives Royal

Assent.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2019

Purpose of the Bill

The primary purpose of the Education

Legislation Amendment (2019 Measures No. 1) Bill 2019 (the Bill) is to amend

the Higher

Education Support Act 2003 (HESA) to give effect to the

commitment, in the Indigenous Youth Education Package in the 2019–20 Budget, to

‘extinguish Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) debt incurred for recognised

teaching qualifications after teachers have been placed in very remote

locations of Australia for four years’.[1]

This commitment was first announced in the Prime

Minister’s Closing the Gap speech of 14 February 2019.[2]

The scheme proposed in the Bill would allow school and

early childhood education teachers employed in very remote locations of

Australia from 1 January 2019 to apply to:

- have

the indexation of their HELP debt frozen while they work in a remote area and

- have

HELP debt for their initial teacher education (ITE) course remitted, following

the completion of four years (or part-time equivalent) in a remote area.

To give effect to the policy commitment, the above applies

retrospectively from 1 January 2019.[3]

The Bill also proposes to:

- amend HESA to give effect to a second 2019–20 Budget commitment to increase

the HELP loan limit for people studying specified high cost aviation courses,

to bring it into line with the limit for medicine, dentistry and veterinary

science students[4]

and

- amend HESA and the VET Student Loans

Act 2016 (VSL Act) to expand information sharing provisions.

A number of minor technical and consequential amendments

have also been included in the Bill. These are not discussed in this Bills

Digest.

Background

Initial

teacher education

The Bill addresses HELP debt associated with teachers’ ITE

courses. An ITE course is ‘a higher education program that is accredited to

meet the requirements for registration as a school teacher in Australia’.[5]

Programs are accredited by each state and territory’s teacher regulatory

authority. Registration of early childhood teachers is required under some

state and territory legislation.[6]

The national Accreditation Standards and Procedures set

out the structure and content requirements for ITE programs.[7]

Graduates undertake a four-year or longer full-time equivalent higher education

qualification that is structured in one of the following ways:

- a

three-year undergraduate degree providing the required discipline knowledge,

plus a two-year graduate entry professional qualification (for example, a

Bachelor of Arts plus a Master of Teaching)

- an

integrated degree of at least four years comprising discipline studies and

professional studies (for example, a Bachelor of Education: Primary; Bachelor

of Education: Early Childhood)

- combined

degrees of at least four years comprising discipline studies and professional

studies (for example, a Bachelor of Education: Secondary and a Bachelor of Arts)

or

- other

combinations of qualifications proposed by the provider and approved by the

Authority in consultation with Australian Institute for Teaching and School

Leadership (AITSL) as equivalent to the above that enable alternative or

flexible pathways into the teaching profession.[8]

In 2018 in Australia, there were 84,426 students enrolled

in ITE courses, of which 67,902 were enrolled at undergraduate level and 16,524

at postgraduate level.

Each year, around 17,000 students complete their ITE

course (see Table 1).

Table 1: enrolments

and completions by course level, initial teacher education courses, domestic

higher education students, 2013–2018

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

| Enrolments |

79,120 |

83,127 |

84,787 |

88,941 |

84,426 |

| Postgraduate |

16,348 |

17,232 |

17,338 |

18,044 |

16,524 |

| Undergraduate |

62,772 |

65,895 |

67,449 |

70,897 |

67,902 |

| Commencements |

29,317 |

29,833 |

28,786 |

29,940 |

25,835 |

| Postgraduate |

9,400 |

8,949 |

8,689 |

8,650 |

7,507 |

| Undergraduate |

19,917 |

20,884 |

20,097 |

21,290 |

18,328 |

| Completions |

17,708 |

17,231 |

16,985 |

17,604 |

16,461 |

| Postgraduate |

7,148 |

6,635 |

6,284 |

6,531 |

5,661 |

| Undergraduate |

10,560 |

10,596 |

10,701 |

11,073 |

10,800 |

Source: Department of Education, Higher Education

Statistics Data Cube (uCube) which is based on the student and staff data

collections.

Note: Undergraduate includes Bachelor's Graduate Entry,

Bachelor's Honours, Bachelor's Pass, Associate Degree, Advanced Diploma (Australian

Qualifications Framework), Diploma (AQF) and other Award courses.

Of all students completing ITE

qualifications in 2016, the proportion of students completing primary and

secondary qualifications was similar, with both at 33 per cent of completions.

Completions in early childhood qualifications comprised 13 per cent of

completions, with the remaining 21 per cent of completions in combined

primary/secondary/early childhood or unspecified ITE qualifications.[9]

Completions in early childhood qualifications have risen steadily, from 1,948

in 2007 to 4,018 in 2016.[10]

Course costs

A domestic student enrolling in a four year undergraduate

ITE degree would currently be in a Commonwealth Supported Place (CSP), which

means their student contribution is capped by the Government.[11]

In 2020, this cap is $6,684 per full time year, equating to costs of around

$26,736 for four years study.[12]

Some Master of Teaching students also receive CSPs, equating to $13,368 for a

two year course.[13]

However, CSPs are not available for all postgraduate

coursework qualifications, which often means students pay full fees, which are

more costly than the ‘student contribution’ required in a CSP. As some

examples:

- the

University of Canberra’s two year Master of Secondary Teaching is $32,000 for

domestic full-fee-paying students, based on 2019 fees[14]

and

- Deakin

University’s Master of Teaching (Primary) is $44,800 for domestic

full-fee-paying students, based on 2020 fees.[15]

The Higher

Education Loan Program

Eligible students can defer the up-front cost of their

student contribution or course fee through HELP. HELP comprises income

contingent loans that are repaid through the Australian Taxation Office (ATO)

once a person’s income reaches a minimum repayment threshold, which is $45,881

with a repayment rate of one per cent for the 2019–20 financial year.[16]

The repayment rate increases according to the taxpayer’s income, to a maximum

of ten per cent on incomes of over $134,573.[17]

A number of different HELP schemes are available depending

on a student’s circumstances.[18]

For eligible higher education students, the schemes to defer course fees are:

- HECS-HELP,

which is used by Commonwealth supported higher education students (that is,

students with a CSP in a course), typically domestic undergraduate students

studying at Australian public universities.[19]

In 2018, 826,572 higher education students used HECS-HELP (97.3 per cent of 849,108

Commonwealth supported students).[20]

- FEE-HELP,

which is used by domestic full fee-paying higher education students.[21]

In 2018, 136,869 higher education students used FEE-HELP (70.5 per cent of

194,237 domestic fee-paying students).[22]

The average time to repay HELP debt is increasing, and

reached 9.2 years in 2018–19, up from 9.1 years in 2017–18.[23]

Educational

issues facing students in very remote locations

Reviews and research over a long period show persistent educational

issues in regional, rural and remote (RRR) settings. A paper presented to the

Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) Conference 2014 stated:

Forty years ago, in the report to the Australian Schools

Commission, Karmel identified several aspects of educational disadvantage

experienced by schools in country areas – including high teacher turnover, low

retention rates, less confidence in the benefits of education, limited cultural

facilities in the community, lack of employment opportunities for school

completers, and a less relevant curriculum – that led to lower levels of

attainment (Karmel, 1973). These issues are still relevant today.[24]

Performance outcomes for students on a range of indicators

worsen with remoteness. There are also substantial overlaps

between remoteness and other sources of educational disadvantage, such as

socio-economic status, and students’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

status.

Students from very remote schools have poorer results on

national and international standardised tests, such as National Assessment

Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) and Programme for International Student

Assessment (PISA).[25]

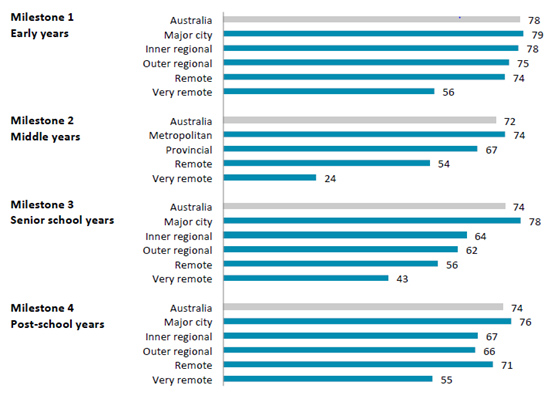

The Mitchell Institute’s report, Educational

Opportunity in Australia 2015: Who Succeeds and Who Misses Out, examined young people’s progress on four key educational milestones:

early years (school readiness), succeeding in the middle years (measured at

entry to secondary schooling), completing school by age 19, and engaged in

education, training or work at age 24.[26]

The report showed that the

proportion of very remote students who met the requirements at each milestone was

between 19 and 48 percentage points lower than for the

Australian population as a whole and that the

achievement gaps between young people in metropolitan and non-metropolitan

areas widened as they progressed through their education (Figure 1).[27]

Figure 1: proportion of students meeting

educational milestones by location

Source: Mitchell Institute, Young people in rural and remote communities frequently

missing out, Equal Opportunity in

Australia 2015, fact sheet 6, Mitchell Institute, Melbourne, 2015.

Remote

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students

Like the non-Indigenous population, the majority of the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population live in non-remote areas.

However, a much higher proportion of the population and hence the school

students in very remote areas are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In the 327 very remote schools which the Minister indicated would be covered by

this measure, approximately 68 per cent, or nearly 20,000, of the students are

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander students, and approximately 189 or 57

per cent of the schools have a student body which is more than 80 per cent

Indigenous.[28]

Poor educational outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander children and students in remote and very remote schools are a major

contributor to the ‘gap’ in overall Indigenous educational outcomes. Despite

some significant improvements over the last decade, Indigenous early childhood

attendance rates in very remote areas were below 80 per cent in 2017, compared

to 95 per cent in urban and inner regional areas.[29]

In the first semester of 2018, Indigenous school attendance rates in very remote

areas were at 63 per cent, compared to 86 per cent in inner regional areas.[30]

NAPLAN results also vary by remoteness; in 2017, 88 per cent of Indigenous Year

3 students in major city and inner regional areas met or exceeded the national

minimum standard for reading, but only 46 per cent of those in very remote

areas met or exceeded the standard.[31]

Early

childhood education

As highlighted in the 2017 Lifting our

Game: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian

Schools through Early Childhood Interventions (ECE Review),

participation in high quality early childhood education (ECE) can improve

students’ performance on tests like NAPLAN and PISA, as well as having a

positive impact on students throughout their subsequent schooling and life,

including school readiness, Year 12 completion, levels of employment and health

outcomes.[32]

These positive effects are greater for vulnerable and disadvantaged children.[33]

Under the National

Partnership Agreements on Universal Access to Early Childhood Education,

governments have committed to the goal of 95 per cent of children being

enrolled in a quality early childhood education program for 600 hours per year

in the year before full-time school.[34]

In 2018, all states and territories exceeded the benchmark.[35]

However, children experiencing disadvantage, including

Indigenous children and children from remote areas, are disproportionately less

likely to be enrolled than the general population.[36]

Additionally, the proportion of children enrolled versus attending the target

600 hours of ECE in the year before fulltime school is lower for children in

very remote areas, and particularly Indigenous children in very remote areas,

than Australian children overall (Table 2).

Table 2: Children

enrolled and attending ECE program (600 hours) in year before school

|

|

Enrolled

|

Attending

|

Percentage

|

|

Children in very remote areas

|

2,492 |

1,575 |

63.2% |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in very

remote areas

|

1,453 |

752 |

51.8% |

|

Total Australian children

|

286,641 |

243,298 |

84.9% |

Source: Parliamentary Library calculations; figures drawn from Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Preschool education, Australia, 2018,

cat. no. 4240.0, ABS, Canberra, 2019. Remoteness area is that of the providers.

Potential attendance barriers

can include costs, service operating hours and location, cultural issues,

distrust of government and early childhood services and staffing issues, such

as recruiting and retaining Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff.[37]

Teachers in

very remote schools

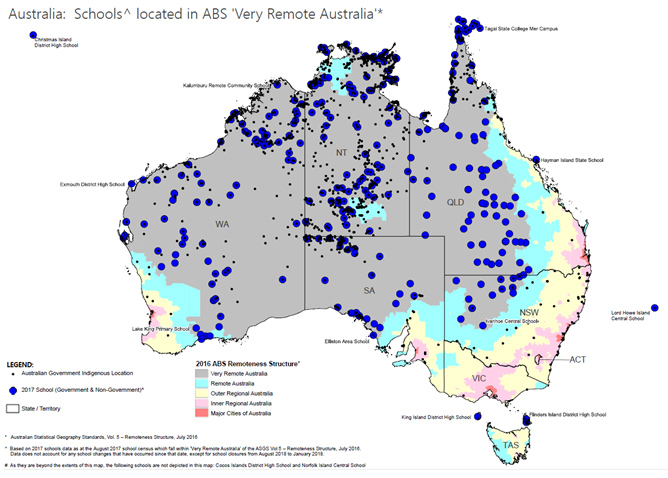

One of the key challenges faced by schools and early

childhood education providers in remote areas is attracting and retaining

teachers. Currently, approximately 3,500 teachers are employed across 327 very

remote schools and 250 early childhood education and care services.[38]

Map 1 shows the location of schools classified as very remote, as well as Australian

Government Indigenous Locations, which are the locations where Australian

Government policies, programs or grants have been, are being, or will be dispersed

for Indigenous persons. Figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

indicate there were nearly 30,000 full time equivalent (FTE) students in very

remote schools in 2018.[39]

There were 2,701 children aged four or five years enrolled in preschool

programs in very remote areas.[40]

A survey of staff in Australian schools last conducted in 2013 found that

remote schools have a higher proportion of early career teachers, the teaching

workforce is less experienced, and teachers and leaders have been at their

current school for a shorter period of time than their metropolitan

counterparts.

- Early

career teachers made up 45 per cent and 30 per cent of the primary and

secondary teacher workforce respectively in remote area schools, compared with

22 per cent of the primary teacher workforce and 18 per cent of the secondary

teacher workforce overall.[41]

- Teachers

in remote schools had on average about 3–5 years less experience than teachers

in metropolitan and provincial schools.[42]

- Primary

teachers in remote areas spent an average of 6.2 years at their current school,

compared with 8.3 years in metropolitan locations, while secondary teachers

spent an average of 5.4 years at their current school in remote areas compared

with 9.3 years in metropolitan areas.[43]

For reasons noted below, the above would appear to suggest

that the Bill will provide financial incentives rewards for early career teachers

rather than experienced teachers. As such, it may result in ‘a windfall gain to

graduates who find out about it’,[44]

rather than acting as a significant incentive that shapes the career decisions

of experienced teachers. In addition, as the four-year qualifying period is

less than the average time spent by primary teachers in remote schools the Bill

may not provide an effective incentive for teachers to remain longer in remote

schools than is currently the case.

Research into remote education consistently identifies

particularly acute challenges for the remote and very remote schools attended

by these Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, including low teacher

retention and high staff churn. The Independent

Review into Regional, Rural and Remote Education (IRRRRE), released in

January 2018 stated:

The fifth critically important matter that needs to be

addressed in regard to teachers is reducing their turnover rate in remote

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander schools and increasing the overall

experience of those who are appointed... Beginning teachers have historically

been one of the main sources of staffing for remote Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander schools. While some succeed and make a very significant

contribution to the children they teach, as I saw at the Soapy Bore Homeland

School in the Northern Territory, there is more that can be done to build the

capacities and experiences of early career teachers before they are

appointed to remote schools. [45]

Map 1: location of schools classified as very remote

Source: Material used 'as supplied': Australian Bureau of

Statistics; StreetPro © 2018 Pitney Bowes Software Pty Ltd. All Rights

Reserved. Derivative material: Based on material supplied by: Dept. of

Education and Training; Dept. of Human Services; Geoscience Australia;

Australian Bureau of Statistics; Australian Electoral Commission. Maps have

been prepared using school data as at the August 2017 school census and do not

account for any changes (such as new schools, name changes, school mergers or

school closures) that have occurred since that date, except for school closures

from August 2017 to January 2018. Australian Government Indigenous Locations

(AGIL) data is current as at 8 February 2019 and contains the names (preferred

and alternate) for the locations where Australian Government policies, programs

or grants have been, are being or will be dispersed for Indigenous persons at

this location. Except as required by law, the Commonwealth will not be liable

for any loss, damage, expense or cost (including any incidental or

consequential loss or damage) incurred by any person or organisation arising

out of use of, or reliance on, this map.

The practical effects of these issues are illustrated in

the 2018 evaluation of the Flexible

Literacy for Remote Primary Schools Program (FLRPSP), which included 35 remote

and very remote, predominantly Indigenous, primary schools across the NT, WA

and QLD, and found:

- average

staff retention in any given year was 42 per cent (that is, on average more

staff left during any given year than stayed for at least one full year), with

some schools reporting staff retention of less than 20 per cent[46]

- 38

per cent of teachers who responded to a staff survey had been at a school for

less than two years and another 42 per cent had been at a school for between

two to five years[47]

and

- high

turnover significantly impacted the schools’ ability to deliver both the normal

curriculum and the specialised Explicit/Direct Instruction curriculum of the

FLRPSP, as there was little continuity of student instruction and mentoring,

and staff training had to be frequently re-delivered to bring new teachers up

to speed.[48]

The above suggests that the provision of financial

incentives of the form proposed by the Bill will largely reward early career

teachers rather than experienced ones.[49]

In addition as the four-year qualifying period is less than the average time

spent by primary teachers in remote schools, the Bill may not provide enough of

an incentive to encourage teachers to remain longer in remote schools than is

currently the case.

In a Statement

to Parliament on Remote Indigenous Education on 6 December 2018, then

Special Envoy for Indigenous Affairs Tony Abbott recommended a scheme similar

to that proposed in the Bill, stating that HELP debts should be waived for ‘teachers

who, after two years of experience in other schools, teach in a very remote

school and stay for four years’.[50] This

recommendation was subsequently cited in the Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap

speech which introduced this measure.[51]

However, Mr Abbott’s statement also pointed to the complexities of the

challenge facing governments in this area, and the need for action on multiple

fronts:

A key factor [in remote school

attendance and performance] is the high turnover of teachers, who are often

very inexperienced to start with. In the Northern Territory's remote schools,

for instance, most teachers have less than five years experience, and the

average length of stay in any one school is less than two years ...

I am much more confident than I

expected to be that, left to their own devices, the states and territories will

manage steady, if patchy, progress towards better attendance and better

performance, but what will be harder to overcome, I suspect, is communities'

propensity to find excuses for kids' absences and school systems' reluctance to

tailor credentials and incentives for remote teachers. This is where the

federal government could come in to back strong, local Indigenous leadership

ready to make more effort to get their kids to school and to back state and

territory governments ready for further innovation to improve their remote

schools.

While all states and territories

provide incentives and special benefits for remote teachers, sometimes, I

regret to say, these work against long-term retention. In one state, for

instance, the incentives cease once a teacher has been in a particular school

for five years. In others a remote teaching stint means preferential access to

more-sought-after placements, so teachers invariably leave after doing the bare

minimum to qualify.

There should be special literacy

and numeracy training, as well as cultural training, before teachers go to

remote schools where English is often a second or third language, and there

should be substantially higher pay in recognition of these extra professional

challenges. Because it takes so long to gain families' trust, there should be substantial

retention bonuses to keep teachers in particular remote locations. We need to

attract and retain better teachers to remote schools and we need to empower

remote community leadership that is ready to take more responsibility for what

happens there. The objective is not to dictate to the states their decisions

about teacher pay and staffing but to work with them so that whatever they do

is more effective ...[52]

One key message from this statement, and the other

research cited above, is that teachers who have more training and support, and

are more experienced, are likely to be better able to work effectively over the

longer term in remote schools, including schools with a high proportion of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. It is also interesting to note

that the Bill differs from the key recommendations put forward by Tony Abbott,

which were subsequently cited in the Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap speech,

that HELP debts should be waived:

- for

teachers with more than two years of experience in other schools who move to teach

in a very remote school and

- who

subsequently stay at the school stay for four years.[53]

As such, there would seem to be a significant risk that the

Bill will not provide a substantial enough incentive for experienced teachers

to take up remote teaching positions. This is because experienced teachers will

have lower HELP balances than graduate teachers or less experienced teachers, and

are a likely to have higher incomes. These factors will combine to potentially

reduce the financial attractiveness of HELP debt waivers as a teacher becomes

more experienced and their income increases over time.

Policy

responses

State and

territory initiatives

In the past teacher recruitment and retention in regional

and remote areas has usually been regarded as a policy issue for state and

territory governments.[54]

State and territory governments have implemented strategies, programs and

incentives to attract teachers into remote schools, such as:

- financial

benefits, such as extra pay and bonuses

- relocation

assistance

- travel

allowances

- additional

leave entitlements

- subsidised

housing or rental concessions and

- additional

professional development opportunities.[55]

However, evidence suggests that incentives such as those

noted above may not be sufficient to overcome the perceived disincentives of

teaching in remote area schools, such as isolation, limited school resources,

and lack of access to support.[56]

The

HECS-HELP benefit

From 2008 to 2017, the Australian Government sought to use

HELP ‘benefits’ to address skill shortages in priority areas.

A 50 per cent reduction in students’ HECS-HELP payments

was announced for selected courses as part of the 2008–09 Budget, with the aim

of encouraging:

- more

students to study maths and science and pursue related careers, including

teaching in those fields[57]

and

- early

childhood teachers to work in regional, remote or high disadvantaged areas.[58]

The discounts commenced in second semester 2008 for

mathematics and science graduates, and second semester 2009 for education and

nursing graduates, and were known as the HECS-HELP benefit.[59]

In part, this Commonwealth involvement was in response to

increased attention to Commonwealth funding and support of disadvantaged and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students through the Closing the Gap

partnerships, as well as the Early Childhood Education Workforce Strategy, the

then National

Partnership Agreement on Early Childhood Education and the Closing the Gap

target of universal access for Indigenous four year olds to preschool

education.[60]

In 2012, the Productivity Commission raised questions

about the effectiveness of reducing student contribution amounts as an incentive

for enrolment in teacher education courses, quoting Chris Evans, then Minister

for Tertiary Education, Skills, Jobs and Workplace Relations stating that

students are ‘predominantly motivated not by price but by their interests,

abilities and career preferences when selecting courses.’[61]

In 2014, the Review of the Demand Driven Funding System

(the Review) recommended the discounts be discontinued.[62]

It found ‘little evidence that HECS‑HELP benefits for graduates in some

courses make a difference’, with benefits going predominantly to people in

occupations with already high uptake, meaning it was likely ‘a windfall gain to

graduates who find out about it, rather than something that shapes their

decisions on courses and careers’.[63]

The Review identified a number of key limitations to the

program:

- course

costs in Australia are not high enough to dissuade students from enrolling,

meaning changes to student contributions tend not to significantly increase

demand for the cheaper disciplines

- low

awareness of the program, resulting in low uptake of less than 2,500 in 2011–12

and 7,220 in 2012–13

- small

financial effects compared with lifetime implications of course choices and

- the

long wait for the financial benefit, which came in the form of a reduced

repayment period after undertaking their course and repaying the 50 per cent

loan they still needed to take out.[64]

In the 2014–15 Budget, in response to the Review, the

Government announced the cessation of the HECS-HELP benefit.[65]

HECS-HELP benefit ceased on 30 June 2017.[66]

In part, the challenges of such programs can be attributed

to the design of HELP itself. The research literature suggests that, by

removing the up-front cost barriers to enrolment and making repayments

contingent on the borrower’s capacity to repay the debt, income contingent

loans make students less responsive to course fee levels.[67]

Response to

the Independent Review into Regional, Rural and Remote Education

The IRRRRE was commissioned in 2017, signalling a renewed

interest in Australian Government efforts to address educational disadvantage in

rural, regional and remote (RRR) settings across education sectors.[68]

The final report of the IRRRRE included 11

recommendations, and in relation to the teaching workforce recommended that the

contexts, challenges and opportunities of RRR schools be explicitly included in

the selection and pre-service education of teachers, for example through

careful selection of candidates, placements during training, subjects in

teacher education dedicated to RRR education, and salary and conditions

packages to encourage experienced teachers to teach in RRR schools for fixed

terms without losing their originating non-RRR positions.[69]

The Government accepted all recommendations of the IRRRRE

report.[70]

The 2018–19 Budget provided $96.1 million over four years to implement the

Government’s response to the IRRRRE, but initial budget announcements focused

on support young people from RRR areas to transition to further education,

training and employment.[71]

The National

Regional, Rural and Remote Tertiary Education Strategy continues the

tertiary education focus of the response.[72]

Key components of the response to the IRRRRE, including in

relation to the teacher workforce, require collaboration with the states and

territories. The IRRRRE report was presented to the Council of Australian

Governments (COAG) Education Council in 2018 and informed—alongside other key

reviews and the ‘Closing the Gap’ agenda—the National

School Reform Agreement, which commenced on 1 January 2019. Under the

reform agreement, governments committed to ‘[r]eviewing teacher workforce needs

of the future to attract and retain the best and brightest to the teaching profession

and attract teachers to areas of need’.[73]

AITSL is leading the developing of the National

Teacher Workforce Strategy and will provide a draft strategy to education ministers

in early 2020.[74]

Committee

consideration

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing, the Senate Standing Committee for

the Scrutiny of Bills had not considered the Bill.[75]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

At the time of writing, no non-government

parties/independents have commented on the measures proposed in the Bill.

Policy

positions of major interest groups

Very remote

HELP debtors

John Halsey of Flinders University, who conducted the IRRRRE,

stated:

The announcement by the Australian Government to encourage

teachers to stay longer in very remote settings by wiping up to five years'

worth of their HELP debt is welcome news.

This additional financial incentive must be carefully

implemented to ensure that teacher quality and expertise remains a top

priority.

As I argued in my report for the Australian Government into

regional, rural and remote education released in 2018, attracting and retaining

top educators for RRR schools and communities needs greater importance and

resourcing being given to all stages of undergraduate preparation, appointing

and supporting a teacher to become a highly competent professional.

Extending the new scheme to include school principals and

positions of additional responsibility such as curriculum coordinators should

also occur.

As well, systems will need to provide tailored, professional

support for teachers and leaders who stay longer in very remote locations than

they might have originally planned to do so.[76]

The Regional Universities Network Secondary

Teacher Education: A View from the Regions, released just after the

Bill was tabled, on 29 October 2019, recommends a range of actions in this area

(as outlined above) but does not identify HELP debt remission for ITE as a

priority.

HELP loan

limit for aviation courses

The Australian Aviation Associations Forum (TAAAF)

chairman Jeff Boyd has been quoted as welcoming the increased loan limit:

This increase will now ensure that pilots will be able to

complete their training with not only bare minimum qualifications, but relevant

and employable qualifications thereby helping to ease Australia’s pilot

shortage.[77]

Information

sharing provisions

At the time of writing, no stakeholder comments on this

aspect of the Bill could be located.

Financial implications

According to the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill:

The measure in Schedule 1 to the Bill (higher HELP loan limit

for certain aviation courses) delivers a positive impact of $45.9 million in

fiscal balance terms over the period from 2019–20 to 2023–24. In underlying

cash terms, the measure provides a minor saving of $1.7 million over the same

period.

The measures in Schedule 2 to the Bill (HELP debt indexation

reduction and HELP debt remittal for teachers working in very remote locations)

have a cost of $94.0 million in fiscal balance terms over the period from

2019–20 to 2023–24. In underlying cash terms, the measures come at a cost of

$28.7 million over the same period.

The measures in Schedule 3 to the Bill do not have financial

implications.[78]

Statement of

Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[79]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights had not considered the Bill.[80]

Key issues

and provisions: HELP debt relief for very remote teachers

Schedule 2 of the Bill deals with HELP debt relief

for very remote teachers. Currently, HELP debt can be cancelled only when:

- a

student is unable to complete a course or unit because of provider or course

closure, and the student has already incurred the debt but cannot be enrolled

in a replacement course[81]

or

- ‘special

circumstances’ apply, meaning a student is unable to complete a unit for which

they incurred a HELP debt in circumstances that were:

- beyond

their control and

- did

not make their full impact known until on or after the census date (at which

point the debt is incurred)[82]

or

- if

the debt was incurred improperly because the person did not provide a tax file

number.[83]

Otherwise, when a person with a HELP debt earns above the

minimum repayment threshold, they must make a repayment through the ATO for that

income year, based on their taxable income.[84]

The repayment rate commences at a rate of one per cent for income over $45,881

and increases according to the taxpayer’s income to a maximum of ten per cent

on incomes of over $134,573.[85]

Under provisions proposed in Schedule 2, a person who is a

very remote HELP debtor will:

- not

have indexation applied to their HELP debt while they teach in a very remote

location and

- have

the HELP debt they incurred in training to be a teacher waived after spending four

years’ full-time equivalent teaching in a very remote location.

However, as noted above evidence from the operation of

previous schemes and research into using various incentives to attract and

retain teachers in remote schools raises questions as to the likely

effectiveness of the regime proposed by Schedule 2 of the Bill. This is

discussed below.

Who is

eligible for reduced HELP debts?

Under the arrangements proposed at item 11, a person

who:

- carries

out work as a teacher at a school located in an area that is

classified as very remote Australia under the ABS Remoteness Structure

- has

completed a course of study in education and

- incurred

a HECS-HELP or FEE-HELP debt in relation to that course of study[86]

will be a very remote HELP debtor and

eligible for the HELP waiver and/or reduced debt indexation (the ‘incentives’).

Each of these elements is discussed below.

What schools

will be covered by incentives?

For the purposes of determining a teacher’s eligibility

for the incentives a school is defined as any of the following:

- an

early childhood education and care service that includes a preschool education

program

- a

preschool

- a

school providing primary or secondary education.[87]

As noted above, to be eligible for the incentives the

school must be in an area that is classified as very remote Australia under the

ABS Remoteness Structure―defined as the most recent update to the

Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) published by the Australian

Statistician.[88]

What courses

of study will be covered by the incentives?

A teacher will only be eligible for the incentives if they

have completed an appropriate course of study in education, defined

as:

- a

course of study, completion of which would satisfy the minimum academic

requirements for registration as a teacher by an authority of a state or

territory or

- a

course of study specified in the Very Remote HELP Debtor Guidelines.[89]

What types

of work will be covered by the incentives?

As noted above, only a person who carries out work as a teacher

in a remote school who has completed an appropriate course of study in

education will be eligible for the incentives. The Bill provides that the Very

Remote HELP Debtor Guidelines (Guidelines) may set out circumstances in

which a person is taken, or taken not, to:

- carry

out work as a teacher on a day or

- carry

out such work at a school located in an area that is classified as very remote

Australia under the ABS Remoteness Structure.[90]

As such, the Guidelines can provide for when a person is

or is not a very remote HELP debtor for particular periods, and

hence eligible for the incentives.

Application

process

A person will need to make an application in writing, in

the form specified, for their HELP debt to be reduced under these arrangements.[91]

The application will need to include the person’s tax file number, and meet any

requirements specified in the Guidelines for the purposes of the application.[92]

The application will be approved if the Secretary is satisfied the person:

- has

been a very remote HELP debtor for a period of four years, or for

periods within a continuous six year period that total to four years

- has

met any other requirements specified in the Guidelines for the purposes of

assessing the application and

- has

not previously had HELP debt for a course of study in education waived under

these provisions.[93]

That is, the application will need to be made to the

Secretary after a person has completed the four years equivalent full-time

teaching at a school in a remote location.

The Secretary will be required to advise the person of the

outcome of their application in writing, including the amount by which the debt

will be reduced, within 28 days of the application being received.[94]

However, if the Secretary does not notify the person, the application will be

taken to have been rejected.[95]

The application and transitional provisions at item 15

mean any time teaching at a school located in an applicable area before 1

January 2019 would not be included for the purposes of assessing whether a

person meets the requirements to be a very remote HELP debtor. However

any time teaching at an eligible remote school from 1 January 2019 will count,

due to the retrospective operation of the relevant provisions in the Bill.

Debt relief

aspect of the incentive

Where an application is approved the person’s HELP debt will

be reduced by:

- the

amount of HECS-HELP or FEE-HELP debt incurred for up to five years full time

study (or equivalent) for a course of study in education or

- the

amount of accumulated HELP debt at the start of their four years as a

very remote HELP debtor, if that amount is less than the above.[96]

The amount the accumulated debt is reduced by is to be

known as the very remote HELP debtor reduction.[97]

Provisions relating to indexation are dealt with separately, as discussed

below.

The proposed arrangements include provision for the effect

of reducing the person’s HELP debt to result in a balance of less than zero.[98]

If this occurs, and the amount below zero is not owed as part of the person’s

primary tax debts, then the additional amount will be refunded.[99]

These arrangements are consistent with current arrangements for people who make

voluntary repayments which exceed their total HELP and tax debts.[100]

The effect of this is that although teachers will be required to wait until

after completing four years as a very remote HELP debtor to make

an application for their debt to be waived, any repayments made during this

time could be refunded.

Arrangements

for reducing HELP debt indexation

Currently, accumulated HELP debts that have remained

unpaid for more than 11 months are indexed on 1 June each year according to the

Consumer Price Index (CPI), to retain the real value of borrowings over time.[101]

In 2019, this was 1.9 per cent, amounting to approximately $426 indexation

added to the average outstanding debt of $22,425.[102]

Indexation

relief aspect of the incentives

Proposed section 142-10 at item 11 would

reduce the indexation of accumulated HELP debts for very remote HELP debtors.

Applications will need to be made to the Secretary in

writing in an approved form (if specified), and accompanied by any required information,

including the person’s tax file number.[103]

Applications will be approved if the Secretary is satisfied a person with an

accumulated HELP debt was a very remote HELP debtor at any time

during the calendar year, and has met any requirements specified in the Very

Remote HELP Debtor Guidelines for the purposes of the application.[104]

If approving an application, the Secretary will be required to determine how

many days the indexation is to be reduced for.[105]

Unlike the requirements for remitting the HELP debt of very remote HELP

debtors outlined above, the application for reducing HELP debt

indexation will be possible during a teacher’s four years’ equivalent as a very

remote HELP debtor, amounting to an indexation pause during this time.

The Secretary will be required to advise the person of the

outcome of their application in writing, including the number of days the

reduction will apply to, within 28 days of the application being received.[106]

However, if the Secretary does not notify the person, the application will be

taken to have been rejected.[107]

Items 6 and 7 have the effect of updating

the definition of HELP debt indexation factor at section 140-10

to reflect these provisions.

Effect of

indexation relief incentive

The effect of the provisions relating to the indexation

relief aspect of the incentive is that a teacher’s HELP debt indexation factor

is reduced in proportion to the number of days in the preceding calendar year

that the Secretary has determined they were a very remote HELP debtor.

Where a teacher has worked the entire previous calendar

year in a very remote location, their accumulated HELP debt will not be indexed

at all that financial year.[108]

The effect

of the incentives

The Bill proposes measures designed to attract and retain

teachers in very remote schools by providing HELP debt reductions for ITE

degrees. In focusing on HELP debt remittance, the proposed initiative is likely

to be relatively more attractive to early career teachers.

In summary, the available research outlined above, shows:

- teachers

in remote schools are on average less experienced than teachers in metropolitan

areas, with this having been identified as a challenge in the IRRRRE[109]

- HELP

debt relief does not seem to significantly impact on career decisions and

instead may result in ‘a windfall gain to graduates who find out about it’

rather than acting as a significant incentive that shapes the career decisions

of experienced teachers[110]

- a

long wait period for HELP debt reduction may act to undermine the

attractiveness of such incentives[111]

and

- other

factors such as candidate selection, training for remote teaching and specific

salary and condition-related incentives, rather than debt relief, may offer more

effective ways to ensure teachers are supported in their work in remote schools.[112]

The proposed initiative will sit alongside work on the

teaching workforce overseen by the COAG Education Council, and existing state

and territory incentives. It leaves open the question of how to address

longer-term sustainability and experience in the remote teacher workforce.

Other provisions

HELP loan

limit for aviation courses

In addition to the higher education HELP loans discussed

above, VET Student Loans (VSL) is an income contingent loan scheme used by vocational

education and training (VET) students studying an approved course at an

approved training provider.[113]

In 2018, 57,874 students used VSL.[114]

VSL has been administered separately from HELP since 1 July 2019.[115]

The HELP

loan limit

Currently, a lifetime limit applies to FEE-HELP and VSL

borrowing. This is known as the ‘FEE-HELP limit’, while the amount a person has

remaining that they can borrow is known as the ‘FEE-HELP balance’.[116]

In 2019, the FEE-HELP limit is $150,000 for medicine, dentistry and veterinary

science students and $104,440 for other students.[117]

At 30 June 2019, 22,514 people had outstanding

HELP debts of above $100,000 (out of a total of almost three million debtors).[118]

Changes already passed by the Parliament provide that from

1 January 2020, the FEE-HELP limit will be replaced by a ‘HELP loan limit’ at

section 128-20 of HESA.[119]

The HELP loan limit will apply to FEE-HELP, VSL, and HECS-HELP. [120]

Unlike the current lifetime limit, the new HELP loan limit will be renewable,

allowing students to increase their HELP balance for future use by repaying

their HELP debt.[121]

VET Student

Loans caps

Students using VSL also have borrowing limits at course

level, as set out in the VET Student Loans

(Courses and Loan Caps) Determination 2016. There are three loan caps,

which are indexed annually and are $5,171, $10,342 and $15,514 in 2019.[122]

Due to the high cost of delivery, the cap for certain specified

aviation-related courses is set at a higher level, $77,571 in 2019.[123]

However, a corresponding higher overall borrowing cap for aviation courses was

not implemented when VSL was introduced in 2017. As discussed below, this means

that many students are unable to afford to complete high-cost qualifications

that are required by industry.

Aviation

Skills and Training in Australia

In June 2018, the Report of the Expert Panel on

Aviation Skills and Training in Australia identified a ‘severe’ and

‘worsening’ skill shortage of aviation personnel in Australia.[124]

The Report identified a range of interacting factors driving the shortage, and

recommended the VSL borrowing limit:

... be raised to $150,000 as the present limit does not support

a student undertaking the full suite of courses needed to progress through to

the basic Commercial Pilot with Instrument Rating and certainly not to instructor

level.[125]

The Report stated that graduates spend at least $100,000

to gain the minimum qualifications for the industry. Fee information for 2018 is

provided in Table 2 below.

Table 2: tuition

fees for pilot licences and ratings, 2018

| Civil Aviation Safety Authority Licence / Rating |

Tuition Feesa |

Explanation of Requirement |

| Commercial Pilot Licence |

$75,000 |

All pilots |

| Multi Engine Command Instrument Rating |

$30,000 |

>99.9% of pilots |

| Flight instructor Rating |

$30,000 |

Specialist requirement, high demand |

| Agricultural Rating |

$15,000 |

Specialist requirement, low demand |

| Multi Crew Co-Operation |

$7,500 |

All airline pilots |

Source: Expert Panel on Aviation Skills and Training in

Australia, Report

of the Expert Panel on Aviation Skills & Training, July 2018, p.

11.

The Report explains:

The implication of the FEE HELP Loan Limit of $102,392 is that

student pilots from a poorer socio-economic background can access funding for

only the Commercial Pilot Licence and the Multi Engine Command Instrument

Rating. This is leading to severe shortages in the industry for pilots with

Flight Instructor Ratings and Agriculture Ratings.[126]

The proposed

HELP loan limit for aviation courses

Schedule 1, item 1 of the Bill proposes to

repeal and replace section 128-20 of HESA, with the effect of adding a course

of study in aviation to the courses with the higher HELP loan limit in

section 128‑20―currently these are courses in medicine, dentistry

and veterinary science.[127]

For the purposes of these arrangements, a course of

study in aviation will be specified in the FEE‑HELP Guidelines, a

legislative instrument made under section 238-10 of HESA.[128]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, the

specified courses will be those that ‘enable a person to qualify for a

Commercial Pilot Licence, and will be based on the courses specified in

Schedule 2 to the VET Student Loans (Courses and Loan Caps) Determination

2016’.[129]

Currently, the specified aviation courses are:

- Diploma

of Aviation (Air Traffic Control)

- Diploma

of Aviation (Commercial Pilot Licence – Aeroplane)

- Diploma

of Aviation (Commercial Pilot Licence – Helicopter)

- Diploma

of Aviation (Instrument Rating)

- Diploma

of Aviation (Flight Instructor)

- Diploma

of Aviation (Aviation Management)

- Advanced

Diploma of Aviation (Chief Flight Instructor) and

- Advanced

Diploma of Aviation (Pilot in Command).[130]

The number of students accessing VSL for each of these

courses in 2018 (latest full year data available) is outlined in Table 3 below.

Diploma of Aviation (Air Traffic Control) and Advanced Diploma of Aviation

(Chief Flight Instructor) are not included in Table 3 as no enrolments in these

programs were recorded in the relevant data sources for 2018.

The application and transitional provisions at item 4

mean the higher limit will apply to anyone studying on or after 1 January 2020;

not only people who enrol after the commencement of the Schedule.

Table 3: Aviation

courses by VSL assisted students and total enrolments, 2018

| Rank (of all VSL

courses) |

Course name |

Total enrolments |

students using VSL |

Loans per enrolment |

Total loans paid |

| 9 |

Diploma of Aviation

(Commercial Pilot Licence - Aeroplane) |

4,331 |

976 |

$31,910 |

$31,144,288 |

| 53 |

Diploma of Aviation

(Instrument Rating) |

1,114 |

171 |

$22,590 |

$3,862,940 |

| 84 |

Diploma of Aviation

(Commercial Pilot Licence - Helicopter) |

436 |

70 |

$57,614 |

$4,032,973 |

| 94 |

Diploma of Aviation (Flight

Instructor) |

274 |

62 |

$20,229 |

$1,254,219 |

| 128 |

Advanced Diploma of

Aviation (Pilot in Command) |

31 |

28 |

$7,602 |

$212,847 |

| 189 |

Diploma of Aviation

(Aviation Management) |

46 |

5 |

$3,895 |

$19,474 |

Source: Department of

Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business, VSL

annual report Jan-Dec 2018 - Table 1 to Table 6 addendum, August 2019,

Table 4; National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), Total

VET students and courses, program enrolments 2015–18, accessed via VOCSTATS, 22 October 2019.

Information

sharing

Part 2 of Schedule 3 of the Bill proposes amendments

to HESA and the VSL Act to expand information sharing and

disclosure provisions to:

- enable

the sharing of personal information in circumstances where an individual gives their

consent for the disclosure of personal information and

- enable

the Secretary of the Department of Education (DoE) and the Secretary of the Department

of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business (DESSFB), to share higher

education and VSL information with Services Australia (formerly the Department

of Human Services (DHS)), and the Department of Social Services (DSS) for the

purposes of implementing the Transforming the

Collection of Student Information (TCSI) initiative.

These amendments do not propose changes to the kind of

information that can be collected under HESA or the VSL Act.

Section 19-70 of HESA currently gives the Minister (currently

the Minister with responsibility for the DoE) wide powers to request, in

writing, statistical and other information related to higher education providers’

provision of higher education and compliance with HESA. Section 53 of

the VSL Act gives the Secretary (currently of DESSFB) similar powers to

request, in writing, that approved VSL providers provide information or

documentation relating to their provision of VET, or compliance with the VSL

Act.

Data requirements are issued each reporting year, and

generally cover student and course information for the calendar year, including

HELP loans, and, for higher education providers, staff and applications and

offers data.[131]

Both VET and higher education providers use the Higher Education Provider

Client Assistance Tool (HEPCAT) to report to the Higher Education Information

Management System (HEIMS).[132]

Provisions

relating to the disclosure of personal information

The Bill proposes to amend HESA and the VSL Act

to allow the disclosure of personal information if an individual’s consent has

been obtained.

It also proposes to amend HESA to allow the

disclosure of personal information where:

- another

Commonwealth law or state or territory law relating to the administration,

regulation, or funding of education requires or authorises such disclosure or

- in

circumstances specified in the Administration Guidelines made for this purpose.

Such provisions are already in the VSL Act.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, ‘offence

provisions need to be amended to recognise the capacity for an individual to

provide consent for the use or disclosure of their information.’[133]

This is consistent with other privacy and information sharing related

legislation.

Under the VSL Act, personal information has

the same meaning as in the Privacy Act 1988.[134]

That is:

- information

or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is

reasonably identifiable:

- whether

the information or opinion is true or not and

- whether

the information or opinion is recorded in a material form or not.[135]

For the purposes of HESA, the information must also

be:

- obtained

or created by an officer for the purposes of Chapter 2 (which

deals with grants for higher education providers) or Chapters 3 and 4

(which deal with HELP loans to students and repayment of loans).[136]

Currently, under section 179-10 of HESA, an officer

commits an offence if they disclose or copy or record personal information

acquired in the course of their employment, except if that disclosure was made

in the course of their official employment.[137]

A penalty of two years imprisonment applies for contravening the section.

Item 10 proposes to add exceptions to these

arrangements to section 179-10 for circumstances where:

- the

person to whom the personal information relates has consented to the disclosure

- the

disclosure is required or authorised by Commonwealth law or

- the

disclosure is required or authorised by state or territory law relating to the

administration, regulation, or funding of education, or is specified in the

Administration Guidelines made for this purpose.[138]

Provisions for the disclosure of VET personal

information are in near identical terms in clauses 73 and 74 of

Schedule 1A. Item 16 proposes to add the same exemptions to these VET

arrangements as are proposed for the higher education arrangements at item

10.[139]

Disclosure of personal information is also dealt with in Part 9 of the VSL

Act. Currently:

- a

VET officer commits an offence if they disclose information obtained in their

capacity as a VET officer and they use or disclose the information, unless that

disclosure is authorised or required under Commonwealth law, or state or

territory law listed in rules made for these purposes[140]

- a

person commits an offence if the person uses personal information disclosed to

an agency, body, or person for purposes permitted under the VSL Act, for

a purpose that is not permitted under the VSL Act.[141]

In each case, a penalty of two years imprisonment applies

for contravention of the sections. Items 21, 22 and 23 propose to

add exceptions to these provisions, that the offence does not apply if the

person to whom the disclosure relates has consented to the use or disclosure.[142]

Provisions

relating to information sharing between Government departments

The more substantive information sharing changes proposed

in the Bill are concerned with enabling the implementation of a single data

reporting point for higher education and VET providers, with access for the

DoE, DESSFB, Services Australia, and the DSS, for the purposes of

administration under their respective Acts.[143]

The proposed changes rely on the Secretary of the relevant

department or departments (currently DoE and DESSFB) authorising the use of

information collected under HESA and the VSL Act for the purposes

of social security administration. Importantly, HESA and VLS Act

information can include personal information.[144]

This means that the information sharing provisions proposed in the Bill will

expand the circumstances in which personal information collected by tertiary

education providers can be lawfully disclosed to the agencies noted above, with

or without the consent of the person(s) to which the information relates.

No changes to social security law are proposed in the

Bill. According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, no amendments to

social security law are required, as, where required, ‘the intention is to

utilise the existing mechanisms in the social security law’.[145]

The Transforming

the Collection of Student Information initiative

In December 2012, the Review of

Reporting Requirements for Universities identified the

university sector as facing particularly burdensome reporting requirements,

stating that, in addition to reporting under HESA, universities also

report to the higher education and VET regulators, relevant state and territory

governments, the Australian Research Council, Department of Home Affairs (then

Immigration and Citizenship), the Department of Defence, Attorney-General’s

Department, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, health regulators,

Centrelink, a range of professional accreditation bodies, the Australian Bureau

of Statistics, and various bodies producing university rankings.[146]

The Government response

to the review agreed to a range of actions to support streamlined data

collection and reduce duplication.[147]

The latest component of work to improve higher education

data collection is the TCSI initiative, which aims to address duplication in

reporting between the DoE’s HEPCAT and Services Australia’s Centrelink Academic

Reassessment Transformation (CART).[148]

CART enables Services Australia to conduct weekly checks of their records

against those of higher education providers to ensure recipients of student

allowances are studying the required 75 per cent of a full time study load.[149]

If discrepancies are identified, a review is conducted, focusing on:

- recipients who have reduced their study load (Part-time)

- recipients who are no longer enrolled (Withdrawn)

- recipients who are unable to be matched with the

institution (No-match)

- recipients who are studying unapproved courses.[150]

According to the DoE:

In November 2017, the Department of Education partnered with

the Department of Human Services (DHS) to redevelop the existing submission

technologies to enable simpler, more flexible reporting processes and better support

data exchange and availability. The Transforming the Collection of Student

Information (TCSI) project is also facilitating the restructuring of the

student data collection, to remove duplication across submissions, simplify

validation processes and improve data quality and timeliness.

The department has engaged in extensive consultation

throughout 2018 and into 2019 to implement changes to data collection. This

commenced in January 2018 with the release of the discussion paper

Redevelopment and Audit of the Higher Education Data Collection and the

establishment of the TCSI co-design group. We have continued to work with the

sector through webinars, the TCSI newsletters and the DHS Service Hub, in

reaching an understanding of your needs and how the TCSI project can meet them.

Reflecting these consultations, we will transition to the new reporting

arrangements by 31 May 2020.[151]

The DoE states that TCSI will reduce duplication, be

simpler to use, and resolve system deficiencies for providers and make DHS

claims simpler, and improve payment accuracy for students.[152]

HESA

information

Division 180 of HESA deals with the disclosure or

use of HESA information. HESA information is defined at section

180-5 as:

- personal

information

- VET

personal information

- information

obtained or created by a Commonwealth officer as a result of a survey of staff, students or former students of

higher education providers or VET providers for the purposes of:

- improving the provision of higher education or VET or

- research relating to the provision of higher education

or VET

- any

other information obtained or created by a Commonwealth officer for the

purposes of HESA or administering HELP.[153]

Currently, the following disclosures are allowed:

- disclosure

of HESA information between Commonwealth officers in the course of their

official employment[154]

- the

Secretary may disclose HESA information to the national higher education

regulator, Tertiary Education Quality and

Standards Agency (TEQSA),[155]

or a member of TEQSA staff, for the performance of duties under HESA[156]

- the

Secretary may disclose HESA information to the National VET Regulator,

the Australian Skills Quality Authority

(ASQA),[157]

or an ASQA staff member, for the performance of duties under HESA[158]

- the

Secretary may disclose HESA information to a person employed or engaged

by a state or territory agency, a higher education provider, a VET provider, or

another body determined by the Minister by legislative instrument, for the

purposes of improving the provision of higher education or VET, or research

relating to higher education or VET[159]

and

- certain

disclosures of HESA information and VET information under the VSL Act

may occur between the Commonwealth officers, the Secretary, and the Commissioner

of Taxation for the purposes of administering HELP under HESA or the VSL

Act.[160]

Item 12 inserts proposed section 180-23,

which would allow the Secretary to disclose HESA information to a person

employed or engaged by an agency under:

Proposed subsection 180-23(3) would allow the

information to be used for the purposes of exercising powers, or performing

functions or duties, of the agency the information is disclosed to.

Currently, the listed Acts are

administered in the Social Services Portfolio. The Human Services

(Centrelink) Act 1997 is the responsibility of the Minister responsible

for Services Australia and the Social Security Act

1991 and Student

Assistance Act 1973 are the responsibility of the Minister responsible

for the Department of Social Services.[161]

VET

information

The VSL Act contains provisions for sharing VET

information for the purposes of the VSL Act or HESA that are in

similar terms to the HESA provisions outlined above, albeit with no

mention of information sharing for higher education purposes. However, the

following additional disclosures are specifically allowed:

- officers

of tuition assurance schemes, and approved dispute resolution schemes may use

VET information[162]

- the

Secretary may disclose VET information to the Australian Competition and

Consumer Commission, and approved external dispute resolution schemes[163]

and

- the

Secretary may disclose VET information to a department, agency or authority of

the Commonwealth, a state or territory, or an enforcement body, if they believe

on reasonable grounds that the disclosure is necessary the purposes of law

enforcement.[164]

Item 19 proposes to add provision for VET

information to be disclosed to a person employed or engaged by an agency under

the same Acts listed in relation to item 12 above.[165]

Item 20 makes the same allowance that the disclosed information be used

for the purposes of the body the information is disclosed to.[166]

Concluding

comments

The main purpose of the Bill is to introduce HELP debt

forgiveness for teachers for ITE courses following the completion of four years

(or part-time equivalent) teaching in a remote area.

The initiative goes some way towards addressing

limitations identified in the literature on previous HELP debt remittance

programs, in that it is directed toward employment choices following graduation

rather than course choice, where it has been shown students are not generally

very responsive to cost. However, some issues still remain in the considerable

gap between the intended choice of employment, and the subsequent financial

benefit (four to six years), and the potential attractiveness of the financial

benefit (most often around $26,736) compared with a teacher’s other

considerations, such as overall career goals, and lifetime earnings.

Despite the new measures being welcomed by Professor

Halsey (author of the IRRRRE), it is worth noting that the proposed scheme

differs from the recommendations of Mr Abbott and the IRRRRE report. Both of

these stressed the recruitment of experienced teachers, with knowledge of the

conditions and needs of remote education, for RRR schools. The measure put

forward offers the greatest incentive to inexperienced teachers who enter very

remote schools immediately after graduating, as any HELP debt they have paid

while gaining additional experience prior to moving to a very remote school

will not be refunded to them; repayments only apply to HELP debt still owed

when a teacher commences a very remote placement. The measures thus offer less

incentive to move to a very remote school the longer a teacher has been in the

workforce. Nor do they offer any particular incentive to teaching students to

do specialised placements or training in remote education, or encourage people

from remote communities to become teachers.

If the legislation is intended to build on Mr Abbott’s and

the IRRRRE’s recommendations, consideration could be given to enabling a

teacher to become a very remote HELP debtor while still undergoing a course of

study in education (for example by completing a placement in a very remote

school while still a student) and/or backdating the date at which a teacher

becomes a very remote HELP debtor for the purposes of determining the amount of

ITE HELP debt that could be remitted, to capture teachers who gain non-remote

experience before working at a remote school.

If implemented, ITE HELP debt remittance will sit

alongside work on the teaching workforce overseen by the COAG Education

Council, and existing state and territory incentives, and its effectiveness may

be shaped by how well-supported teachers in remote areas are through these

other areas of work.

[1]. Australian

Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2019–20, p. 153.

[2]. S

Morrison, ‘Ministerial

statements: Closing the Gap’, House of Representatives, Debates,

14 February 2019,

pp. 13396–13401.

[3]. Education

Legislation Amendment (2019 Measures No. 1) Bill 2019, proposed Schedule

2, Part 1, Schedule 2, Part 2, item 15; Explanatory

Memorandum, Education Legislation Amendment (2019 Measures No. 1) Bill

2019, pp. 18 (example 1), 23–24.

[4]. Australian

Government, Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2019–20, pp. 71–72.

[5]. Australian

Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), InSights: initial

teacher education: data report 2018, AITSL, Melbourne, 2018.

[6]. Australian

Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA), ‘Early

childhood teacher registration and accreditation’, ACECQA website, n.d.

[7]. AITSL,

Accreditation

of initial teacher education programs in Australia: standards and procedures,

AITSL, Melbourne, 2018.

[8]. Ibid.,

p. 13.

[9]. Ibid.,

p. 13. These figures are the latest available breakdown of this kind, and

include both domestic and international students.

[10]. Ibid.,

p. 10.

[11]. Department

of Education (DoE), ‘Commonwealth

supported places (CSPs)’, StudyAssist website.

[12]. DoE,

‘Student

contribution amounts’, StudyAssist website. Specific costs will be based on

the mix of units the student takes. For 2020, units in humanities, behavioural

science, social studies, education, clinical psychology, foreign languages,

visual and performing arts, and nursing are capped at $6,684 per full time

year; units in computing, built environment, other health, allied health,

engineering, surveying, agriculture, mathematics, statistics, and science, are

capped at $9,527 per full time year; and units in law, dentistry, medicine,

veterinary science, accounting, administration, economics, and commerce are

capped at $11,155 per full time year. These amounts are indexed each year.

[13]. For

example, see Southern Cross University (SCU), ‘Master

of Teaching’, SCU website; The University of Queensland (UQ), ‘Teaching

(Secondary)’, UQ website; Deakin University, ‘Master of

Teaching (Primary)’, Deakin University website; Australian Catholic

University (ACU), ‘Master

of Teaching (Secondary)’, ACU website; University of Melbourne (UoM), ‘Master

of Teaching (Primary)’, UoM website; University of Adelaide, ‘Master

of Teaching (Middle and Secondary)’, University of Adelaide website.

[14]. University

of Canberra (UC), ‘Master

of Teaching - 246JA’, UC website.

[15]. Deakin

University, ‘Master

of Teaching (Primary)’, op. cit.

[16]. Higher

Education Support Act 2003 (HESA), subsection 154(1); Australian Tax

Office (ATO), ‘Study

and training loan repayment thresholds and rates’, ATO website, last

modified 4 June 2019.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. An

introduction to the HELP loans is available from C Ey, Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide,

Research paper series, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2 May 2017.

[19]. DoE,

‘HECS-HELP’,

StudyAssist website.

[20]. DoE,