Bills Digest No. 73,

2018–19

PDF version [1162KB]

Karen Elphick

Law and Bills Digest Section

1

April 2019

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Key issues and provisions

Date introduced: 14

February 2019

House: Senate

Portfolio: Regional

Services, Sport, Local Government and Decentralisation

Commencement: On proclamation

or six months after Royal Assent, whichever occurs first.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at April 2019.

Glossary

| AAA |

Australian Athletes Alliance |

| AAF |

Adverse analytical finding |

| AAT |

Administrative Appeals Tribunal |

| ADRV |

Anti-doping rule violation |

| ADRVP |

Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel—a body created by the ASADA

Act |

| AFL |

Australian Football League |

| AGD |

Attorney-General’s Department |

| AOC |

Australian Olympic Committee |

| ASADA |

Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority |

| ASADA Act |

Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006 |

| ASADA CEO |

ASADA Chief Executive Officer |

| ASADA Regs |

Australian Sports

Anti‑Doping Authority Regulations 2006 |

| ASC |

Australian Sports Commission—now known by the brand name

Sport Australia |

| ASDMAC |

Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee—a body

created by the ASADA Act |

| ASWS |

Australian Sports Wagering Scheme |

| CAS |

Court of Arbitration for Sport |

| Code |

World

Anti-Doping Code 2015 (as amended in 2018). All NSOs must have

anti-doping rules and policies that comply with the Code. |

| COMPPS |

Coalition of Major Professional and Participation Sports |

| ESSA |

Exercise and Sports Science Australia – an accrediting

body |

| ICAS |

International Council of Arbitration for

Sport |

| ICCPR |

International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Australia ratified the ICCPR

in 1980 and it is in force, but it is not fully implemented domestically.[1] |

| Macolin Convention |

Council

of Europe Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions.

Australia signed the convention on 1 February 2019 but has not yet ratified it.[2] |

| NADO |

National Anti-Doping Organisation |

| NAD scheme |

National anti-doping scheme. Authorised by the ASADA

Act, the scheme is contained in Part 2 of the ASADA Regs. |

| NRL |

National Rugby League |

| NSIC |

National Sports Integrity Commission—a generic name for body

proposed in the Wood Review. The Government has said the body will be called

Sport Integrity Australia. |

| NSO |

National Sporting Organisation—a generic name for a peak

governing body for a sport |

| NST |

National Sports Tribunal—a tribunal proposed by the Wood

Review |

| PEIDS |

Performance and image enhancing drugs |

| SCB |

Sports Controlling Body |

| SIA |

Sport Integrity Australia |

| SportAus |

Sport Australia (the operating

brand name of the Australian Sport Commission) |

| WADA |

World Anti-Doping Authority |

| Wood Review |

Report of the review of Australia’s Sports Integrity Arrangements

2018 |

Purpose of

the Bill

The 2018 Report

of the Review of Australia’s Sports Integrity Arrangements (Wood

Review) recommended a range of reforms aimed at enhancing Australia’s

anti-doping capability to address contemporary and foreseeable doping threats.[3]

In Safeguarding

the Integrity of Sport—the Government Response to the Wood Review

(Government Response), the Government agreed or agreed in principle with most

of the recommendations and indicated an intention to take a two stage approach to

implementation.[4]

The Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment (Enhancing Australia’s Anti-Doping

Capability) Bill 2019 (the Bill) is one of a package of three Bills

implementing part of the first stage of the Government Response. The purpose of

this Bill is to strengthen and streamline the

anti-doping regime by:

- abolishing the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel (ADRVP) and the

right to appeal to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

- extending statutory protection against civil actions to National

Sporting Organisations (NSOs)

-

lowering the burden of proof threshold for the chief executive

officer of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA CEO) to issue a

disclosure notice and

- removing the privilege against self-incrimination in relation to

disclosure notices.

- The two other Bills in this first stage package are:

- the National

Sports Tribunal Bill 2019 and

-

the National

Sports Tribunal (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions)

Bill 2019.

Structure of

the Bill

The Bill has one schedule with four parts which amend the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006 (ASADA Act):

Part 1—Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel

Part 2—Protection from civil actions

Part 3—Disclosure to courts or tribunals and

Part 4—Disclosure notices.

Part 1 also makes minor consequential amendments to the Australian Sports

Commission Act 1989 (the ASC Act).

The National

Anti-Doping Scheme

The National Anti-Doping Scheme (NAD scheme) assists

sports to meet their anti-doping obligations, in particular those imposed by

the World

Anti-Doping Code 2015. The NAD scheme is contained in Schedule 1 to the Australian Sports Anti‑Doping

Authority Regulations 2006 (ASADA Regs). The ASADA CEO may amend the

NAD scheme by legislative instrument after public consultation.[5]

The NAD scheme may also be amended by regulation.

Division 2 of Part 2 of the ASADA

Act requires certain matters to be in the NAD scheme. The proposed

amendments in Part 1 make changes to the

requirements for the NAD scheme, rather than to the NAD scheme itself. Consequential

amendments to the ASADA Regs will be required.

The ASADA Act

establishes ASADA to assist the ASADA CEO with a variety of statutory duties

including those conferred by the NAD scheme.[6]

The ASADA Act also

creates the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel (ADRVP) and the Australian Sports

Drug Medical Advisory Committee (ASDMAC).[7]

The ADRVP has various functions, including those conferred by the NAD scheme.[8]

Currently the NAD scheme provides that the ADVRP’s functions include satisfying

themselves that there has been an anti-doping rule violation and requesting the

ASADA CEO to issue an infraction notice.[9]

Background

International

anti-doping obligations

In 1999 the International Olympic Committee convened a

conference in Lausanne to discuss anti-doping. This resulted in the World

Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) being established in late 1999 to promote and coordinate the fight against doping in

sport internationally.[10] WADA

developed the World Anti-Doping Code (the Code) which first came into force in

2004.[11]

[The Code] is the core

document that harmonizes anti-doping policies, rules and regulations within

sport organizations and among public authorities around the world.[12]

As governments were not bound by the [Code], in October 2005

the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

adopted the International Convention against Doping in Sport. Parties to

this Convention (of which Australia is one), are required to implement the

[Code].[13]

One of the intriguing effects of the [Code] and the NAD

scheme is the inclusion of Australian sports that are neither Olympic nor

international into an international anti-doping regimen. The same observation

can be made in respect to athletes who are ‘merely club-players’. The reason

for this inclusion lies in part with the aim of WADA to achieve a ‘unified and

harmonised’ system.[14]

The ASADA Act obliges the

NAD scheme to implement Australia’s international anti-doping obligations.[15]

The NAD scheme applies to all persons who compete in sport, if the sport has an

anti-doping scheme, and to all athletes.[16]

Sport bodies are subject to what has been called ‘soft’ coercion to adopt the

Code because sport bodies must have an anti-doping code before they can receive

government funding.[17]

Once the sporting bodies implement an anti-doping policy, athletes are required

to agree to it in their athlete contract or sporting body membership

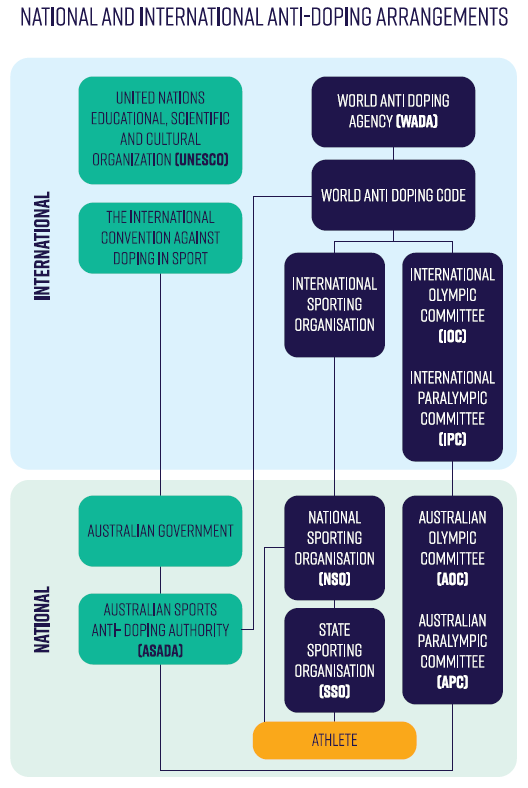

application to comply with the anti-doping policy. (See Flowchart 1

below).

Flowchart 1:

National and international anti-doping arrangements[18]

The net effect is that all

Australian athletes at state, national or international level, and many

athletes at club level (through membership of affiliated sporting bodies), are

subject to the Code.

The Wood

Review

The Wood Review was a comprehensive examination of sports

integrity arrangements, set up by the Government ‘in response to the growing

global threat to the integrity of sport’.[19]

It considered issues around prevention, investigation, and administrative

responses to match fixing and doping. The Wood Review consulted widely and made

52 recommendations.

The centrepiece of the Wood Review recommendations is the

formation of a National Sports Integrity Commission (NSIC) to manage sports

integrity matters at a national level. The Government has announced that it

will form the NSIC and it will be called Sport Integrity Australia (SIA).[20]

Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) President

John Coates, who is also President of the International Council of Arbitration

for Sport (ICAS) and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), described the

Integrity Review [Wood Review] and recommendations as ‘timely and the most

comprehensive national response of its kind I’ve read’.[21]

This Bill is focused on the parts of the

Wood Review dealing with improving anti–doping measures. The key findings of

the Review on this topic and a summary of recommendations can be found in the

introduction to Chapter 4 of the Wood Review at pages 104 to 107.

Government

response

Related to the NSIC, the Wood Review recommended:

That the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA) be

retained as Australia’s National Anti- Doping Organisation and that the current

requirement for all National Sporting Organisations (NSO) (including sports

with competitions only up to the national level) to have anti-doping rules and

policies that comply with the World Anti-Doping Code also be retained.[22]

The Government did not support ASADA remaining an

independent organisation and Australia’s National Anti-Doping Organisation

(NADO). It is the Government’s intention to incorporate ASADA into SIA at some

point in the future.[23]

Stakeholders appear to support this approach (see below).

The recommendation that all NSOs continue to comply with

the Code was not supported by all sports and their opposition is discussed

below under the heading ‘Positions of major interest

groups’. However, the Government agreed with the Wood Review that NSOs

should continue to have Code-compliant anti-doping policies.[24]

The Government agreed with 22 of the Wood Review

recommendations, agreed in-principle with 12 and a further 15 were agreed

in-principle for further consideration. Two recommendations were agreed in part

and one was noted.[25]

The most relevant portion of the Wood Review to this Bill is Chapter 4: The Capability of the Sports Anti-doping Authority and

Australia’s Sports Sector to Address Contemporary Doping Threats.[26]

The Government Response

indicated that it would take a phased approach: some of the important

recommendations will be implemented immediately while more complex

recommendations will be further considered and implemented at a later stage.[27]

This Bill is part of the first stage and implements Wood Review recommendations

17, 19, 23 and 24 in part or in full.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Bill was considered by the Senate Standing Committee

for the Scrutiny of Bills (Scrutiny of Bills Committee) on 28 March 2019. The

Committee reported two scrutiny concerns in Scrutiny Digest 2/19.[28]

Removal of

merits review

The Committee noted its scrutiny concerns regarding the

proposal to remove review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal of assertions

by the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel in relation to potential anti-doping

rule violations (consequential on the abolition of the Panel). The Committee

considered that the explanatory materials do not adequately address these

concerns, and drew this matter to the attention of the Senate.

This issue is discussed further below under the heading

‘Part 1—Abolishing the ADRVP and appeal to the AAT’.

Privacy

The Committee noted its scrutiny concerns regarding the

expansion of the basis on which persons may be required to disclose certain

information and the impact this may have on the right to privacy. The Committee

considered that the explanatory materials do not adequately address these

concerns, and drew this matter to the attention of the Senate.

This issue is discussed further below under the heading

‘Key issues and provisions’ and ‘Part 4—Lowering the burden of proof for issue

of a disclosure notice’.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

On 1 August 2018, Senator Don Farrell, Shadow Minister for

Sport, issued a media release stating that Labor welcomed the release of the

Wood Review and urging the Government to consult with national sporting

organisations and other key stakeholders.[29]

As at the date of writing this Bills Digest, it appears that no non-government

parties or independents have indicated a position on the Bill.

Position of major

interest groups

While there have been no statements from major interest

groups on the Bill as drafted, there was extensive consultation during the Wood

Review and some groups have issued statements about the Government Response.

ASADA

ASADA fully endorses the Government Response, including the

formation of SIA.[30]

Australian

Olympic Committee

The AOC supports all the recommendations of the Wood

Review, ‘As for Anti-Doping Rule Violation matters, the AOC fully

supports the establishment of a National Sports Tribunal and generally on the

basis proposed’.[31] It also commends the Government Response, while saying it would

continue to study it and questioning whether the Government had committed

sufficient funding.[32]

Paralympics

Australia

Paralympics Australia welcomes the Government Response. CEO

Lynne Anderson said:

Paralympics Australia also supports the concept of a new

National Sports Tribunal, which is proposed to hear anti-doping rule violations

and other sports disputes, and resolve them in a consistent, cost-effective and

transparent manner.[33]

Coalition of

Major Professional and Participation Sports

The Coalition of Major Professional and Participation

Sports (COMPPS) represents the major participation sports in Australia

including Australian football, rugby, football, cricket, rugby league, netball

and tennis. COMPPS submission to the Wood Review on funding levels for ASADA to

combat anti-doping states that, ‘Currently, ASADA is insufficiently funded and

resourced to provide the type, and level, of support being sought by the

Sports. Previously, ASADA had a strong detection and investigation arm’. [34]

It notes that each sport it represents has ‘now established its own integrity

unit with responsibility for managing [anti-doping rule violation] ADRV

processes’.[35]

Despite this ongoing allocation of resources, we submit that

current arrangements are not capable of adequately addressing the doping

threat. Specifically, we contend that the Sports are not being given the

support that they require by ASADA to effectively combat the current doping

threat ... Accordingly, ASADA has been unable to satisfactorily perform a number

of its vital functions that support the Sports’ ADRV processes.[36]

Exercise and

Sports Science Australia

Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) is an

accrediting body for professional support personnel and sports scientists. It

supports the findings in chapter 4 of the Wood Review.[37]

Australian

Athletes Alliance

The Australian Athletes Alliance (AAA) is the peak body for Australia’s elite professional

athletes, through eight major player and athlete associations that cover

professionals in cricket, AFL, netball, basketball, football, rugby league,

rugby union and horse-racing (jockeys).[38]

AAA asked the Wood Review to endorse sport-specific, differentiated,

anti-doping and sanction regimes – an approach which would result in those

regimes not being Code-compliant.[39]

The Wood Review saw no

merit in that approach:

In our view, there is no overall

benefit from changing the present policy and thereby creating a dual system in

Australia for national-level athletes. No evidence has been submitted to the

Review which would warrant such an amendment to current anti-doping

arrangements.

The independence and objectivity

inherent in applying the Code to all Australian sports makes for a simpler,

clearer and consistent anti-doping system, beyond the reach of internal sport

politics and collective bargaining.

Accordingly, we do not agree with

AAA’s argument regarding the reach of the Code in relation to sanctions or the

‘fit’ of the world anti-doping system overseen by WADA. Our view is that

penalties under the Code are sufficiently flexible to allow for effective

application in a professional team-sports environment. [40]

The approach of the Wood Review is consistent with the

aims of WADA:

An aim of the 2015 Code is to unify doping regulations

throughout the world, such that the Code might be considered similar to a body

of international law ... In respect to the [Code’s] reach into sports of

national, rather than international operation the Code describes a purpose, ‘To

ensure harmonized, coordinated and effective anti-doping programs at the

international and national level with regard to detection, deterrence and

prevention of doping.[41]

Commonwealth

Games Australia

Commonwealth Games Australia (CGA) supports the consolidation

of existing Federal Government functions in sports integrity under a new agency

– Sport Integrity Australia – and the conduct of a two-year pilot of a new

National Sports Tribunal. CGA also supports the signing of the Macolin Convention. CGA President Ben Houston said

the National Sports Tribunal will benefit Commonwealth Games member sports,

many of whom struggle with the resourcing in this area.[42]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, the Bill will

have no financial impact on the Commonwealth.[43]

The AOC and COMPPS both argued that a further commitment of Commonwealth

funding is necessary to ensure the NAD scheme is effective.[44]

In terms of the NSOs, some smaller sports see financial benefit in having

access to a nationally resourced sports tribunal.[45]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[46]

The Government acknowledges at page 2 of the Explanatory

Memorandum that the Bill engages the following rights:

- Article 2(3) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

– right to an effective remedy.

- Article 14(2) of the ICCPR –

right to presumption of innocence (which includes the right not to be compelled

to self-incriminate[47]).

- Article 17 of the ICCPR –

privacy and reputation.

The Explanatory Memorandum discusses the human rights

issues in detail in the Statement of Compatibility

with Human Rights at pages 2–7. The Bill removes two opportunities for

an athlete or support person to contest the evidence and process involved in

the imposition of an infraction notice for an ADRV. However, the recipient is

still given:

- an opportunity to be heard before the infraction notice is issued

and

-

the opportunity to contest the notice in an independent tribunal.

The Government considers that the rights to a fair hearing

and a presumption of innocence are, therefore, largely preserved. However, as

the Bill will lower the standard of proof for the issuing of a disclosure

notice, it would appear that the Bill engages the right not to be compelled to

self-incriminate under the ICCPR and also the

common law privilege against self-incrimination.[48]

Threshold for

issuing coercive disclosure notices and the privilege against

self-incrimination

Proposed amendments to paragraph 13(1)(ea) and paragraphs

13A(1A)(a) and (b) of the ASADA Act (at items

46 and 47 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) change

the standard of proof for the issue of a disclosure notice from ‘reasonably

believes’ to ‘reasonably suspects’. This change in

threshold, as well as the repeal by item 13 of Part 1 of the need for

three ADRVP members to agree with the notice, will result in a reduced

threshold for the issue of a coercive disclosure notice.

The Guide to

Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement Powers

(the Guide), published by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), says that a

document disclosure provision should normally impose a threshold of ‘reasonable

grounds to believe’ that a person has custody or control of documents,

information or knowledge which would assist the administration of the

legislative scheme.[49]

The proposed disclosure notice provisions and their

justification are discussed further under the ‘Key

issues and provisions’ and ‘Part 4’ headings

below.

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, the Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights had not yet reported on this Bill.

Key issues and provisions

Constitutional

basis for legislation

The Wood Review noted:

The anti-doping framework, both domestically and

internationally, is highly complex; it involves national and international governance,

private corporations and NGOs in a complicated web of contractual agreements,

private arbitration and government regulation which operates both coercively

and by way of moral imperative and reputational protectionism.[50]

While there is no express Commonwealth legislative power

for regulating sport or athlete drug use, section 3 of the ASADA Act identifies implementing Australia’s

international anti-doping obligations as the foundation for the Act. Australia

is a party to several international conventions which provide a basis in the external

affairs power for Parliament to legislate. The ASADA

Act and ASADA Regs implement the Council of Europe Anti-Doping Convention 1989,[51]

the UNESCO International Convention against Doping

in Sport,[52] and the Code. The Commonwealth is therefore able

to rely on the external affairs power as the primary source of its power to

legislate in this area.[53]

The voluntary submission to the Code and NAD scheme by

organisations, athletes and other personnel through contracts extends the effective

reach of the NAD scheme. Voluntary contractual submission to an anti-doping

code means that a constitutional challenge should never be effective on its own

to overturn an ADRV infraction.

Contractual submission is effectively coerced in three

ways:

1. International sporting organisations require regional and national

sporting organisations have a Code-compliant anti-doping policy in order to be

recognised as affiliated. If a body is not affiliated, athletes from that body

cannot compete in higher level events.[54]

2. Organisers of international competitions and major events require

participants to be subject to a Code-compliant anti-doping policy or they are

not permitted to compete.[55]

3. Government funding to national level sporting bodies is made conditional

on compliance with the Code. To be eligible for government funding a sporting

organisation must be recognised as an NSO by SportAus.[56]

To be recognised as an NSO, the organisation must have a Code-compliant,

ASADA-approved anti-doping policy.[57]

To achieve a compliant policy, the NSOs require:

- athletes

to submit to the policy to be eligible to compete

- support

personnel to submit to be allowed to work or volunteer and

- state

sporting organisations to submit to the policy in order to be affiliated.[58]

The Wood Review noted:

Anti-doping arrangements operate fundamentally on a ‘sport

runs sport’ basis, with the adoption of Code-compliant anti-doping policies

being a precondition for continued international recognition and government

support.

In Australia, this manifests in NSOs developing and

implementing Code-compliant, ASADA-approved policies; committing their athletes

and support persons, through contractual arrangements, to abide by these

policies; working with ASADA as the Australian NADO to implement effective

anti-doping activities; and, through referral of ADRVP assertions from ASADA,

being responsible for making the final decision on possible ADRVs. [59]

Part 1—Abolishing

the ADRVP and appeal to the AAT

History of

the Anti-Doping Review Panel

The ADRVP was created by amendments inserted in the ASADA Act in 2009.[60]

ASADA was set up in 2006 and assumed the functions of a variety of existing

agencies. It took over roles in drug testing, education and advocacy from the

Australian Sports Drug Agency; it took over the Australian Sports Commission’s

(ASC) policy development, approval and monitoring roles; it incorporated the

ASDMAC and was given the power to investigate all allegations of ADRV in the

Code. The CEO of the Australian Sports Drug Agency was appointed ASADA CEO and

a Board headed by the ASADA Chair was appointed.[61]

The Australia Olympic Committee (AOC) extensively

criticised the intertwined nature of the ASADA governance arrangements at the

time it was set up. AOC President, John Coates said ASADA would become

investigator, prosecutor, judge and jury.[62]

The AOC considered there was insufficient provision for

the separation of the ASADA‘s policy making, administrative, investigative and

prosecution functions. It particularly noted that there needed to be proper

protection of the rights and roles of Australian sports organisations, athletes

and athlete support personnel. The investigative regime to be put in place did

not require ASADA to put its case to an independent hearing before declaring an

athlete guilty, the AOC noted. And once an investigation was complete, ASADA

alone had the power to determine whether an athlete should be sanctioned.[63]

In response to a number of controversial doping

investigations, the governance arrangements were changed in 2009 to create a

marked distinction between the administrative and investigative functions and

the adjudication functions of ASADA.[64]

The ASADA Chair position was abolished and financial and administrative functions

concentrated in a new ASADA CEO position. Instead of the Board, a specialist

Advisory Group was formed solely to give advice to the CEO in relation to the

CEO’s functions. The group had no adjudicatory or administrative functions. The

ADRVP was established to take on the quasi-judicial role of deliberating on

rule violations. Day to day anti-doping policy issues were confined to the

administrative sector.[65]

In some respects, the Wood Review proposes undoing those

2009 changes. However, the AOC does not oppose the proposed amendments.[66]

The duplicated process was designed to provide an independent check on the

power of the ASADA CEO to issue infraction notices. Stakeholders agreed,

however, that this had not been the practical outcome of the system. Instead it

had resulted in a cumbersome, time wasting process that was of little

assistance to the sports tribunal.[67]

Wood Review

consideration of ADRV process

The Wood Review examined the current ADRV process and

found it was overly bureaucratic, inefficient and cumbersome.[68]

The Coalition of Major Professional and Participation Sports (COMPPS) told the

Wood Review:

The ADRV process is generally convoluted and confusing, and

difficult for athletes and other stakeholders to understand. It is too

bureaucratic, involving an inordinate number of procedural steps.[69]

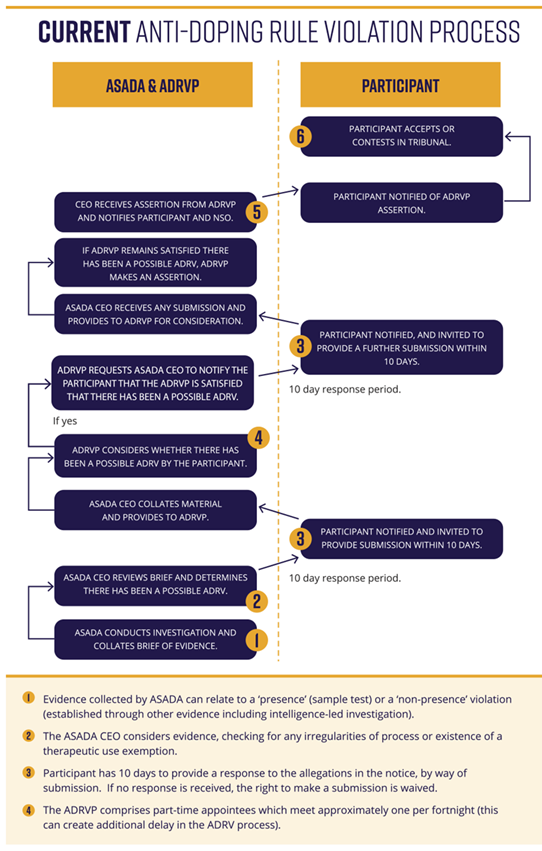

The current ADRV process requires:

- consideration of evidence by the ASADA CEO and

-

a second consideration by the ADRVP

before an infraction notice is issued. Flowchart 2 below shows the process visually.

ASADA estimates that the minimum time to pass from the

ASADA CEO ‘show cause notice’ through to the end of the ADRVP process is eight

weeks.[70]

The decision by the ADRVP to assert an ADRV (marked ‘5’ in Flowchart 2 below) can then be challenged in the

Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT). The WADA Code provides that anti-doping

decisions can be appealed to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS).[71]

Appeals can be made to the CAS Appeals Arbitration Division and the Swiss

Federal Tribunal.[72]

ASADA noted that the ADRVP has never once overruled the

ASADA CEO. The ADRVP Chair explained:

The threshold that the Panel applies is that there is a possibility that an ADRV has occurred. In practice

this has meant that the Panel hasn’t ever disagreed with the CEO, as the threshold that the CEO applies is higher in the first

instance.[73] [emphasis added]

Flowchart 2—Current ADRV process[74]

COMPPS recommended that the ADRVP be abolished.[75]

ASADA suggested that the opportunity for an athlete to respond to an ADRV

allegation be deferred until the infraction notice is received.[76]

However, the Wood Review considered that issuing the ‘show

cause notice’ had the merit of allowing the athlete the opportunity to engage

with the allegations prior to hearing and potentially avoid delays at the

hearing or avoid a hearing altogether if the athlete acknowledges the

infraction.[77]

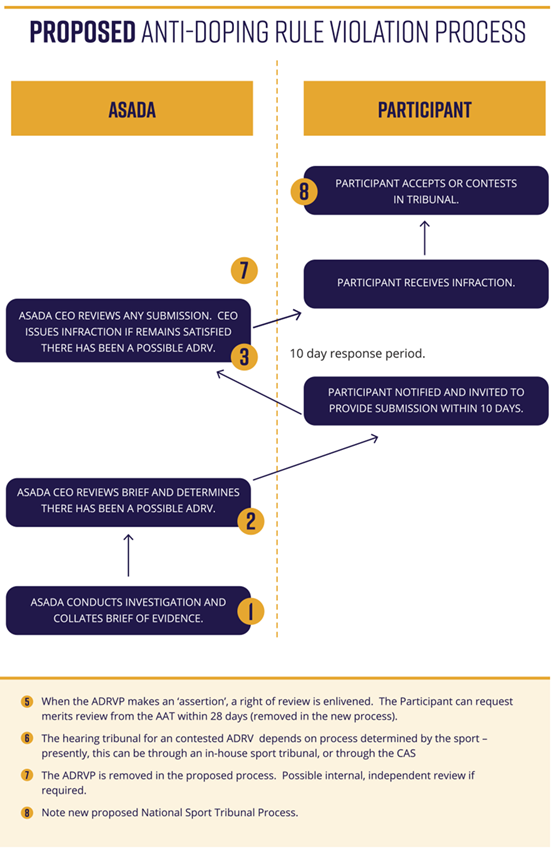

It therefore proposed removing the ADRVP but allowing the athlete an

opportunity to be heard before the ASADA CEO issues an infraction notice.[78]

The Wood Review also recommended abolition of appeals to

the AAT.[79]

For the purposes of procedural fairness, there is no need for

any aspect of the pre-hearing phase of the ADRV process to be subject to AAT

review.

In our view, so long as participants have the opportunity to

respond to allegations before the issue of an infraction notice – and have

access to an affordable, efficient, and effective tribunal to have their matter

heard should they elect – recourse to the AAT for a merits review of any aspect

of the pre-hearing ADRV process is unnecessary and potentially dilatory.[80]

Under the Wood Review proposals, the athlete would then

contest the notice in the proposed NST. Appeal to CAS Appeals Arbitration

Division will also still be available.[81]

It appears that the athlete’s right to a fair hearing and

an effective remedy are preserved under the proposed process. The amendments

proposed in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill appear to maintain compliance with

Australia’s international obligations under the ICCPR,

Council of Europe Anti-Doping Convention 1989

and the UNESCO International Convention against

Doping in Sport.

All major interest groups supported the recommendation.

The Government agreed with the recommendation and the recommended process (see Flowchart 3 below) is reflected in the Bill.

Item 16 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill repeals existing subsection

14(4) of the ASADA Act which requires the

NAD scheme to establish a right of appeal to the AAT. A consequential amendment

to the NAD scheme will be necessary to abolish the right to appeal to the AAT

for review of a decision of the ADRVP.[82]

Flowchart 3—Proposed

ADRV process[83]

Part 2—Protection

of NSO personnel from civil actions

The ASADA Act protects

the ASADA CEO and staff against civil action relating to the performance of the

powers and functions of the CEO provided they have acted in good faith.[84]

However, the NAD scheme requires NSOs to also perform some functions of the

ASADA CEO. The Wood Review recommended that the government extend statutory

protection against civil actions to cover NSO’s in their exercise of ADRV

functions.[85]

Protection may

be broader than intended

Proposed subsection 78(5)

of the ASADA Act (at item 43 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) will extend a

potentially much broader protection from civil action than currently applies to

ASADA:

(5) A national

sporting organisation of Australia, or a person performing work or services for

the organisation, is not liable to an action or other proceeding for damages

for or in relation to an act done or omitted to be done in good faith in

implementing or enforcing the organisation’s anti-doping policy.

The provision protecting ASADA staff is limited to action

pursuant to the CEO’s functions or powers. Proposed

subsection 78(5) covers all actions taken in implementing or enforcing

the organisations anti–doping policy. The actions are not limited to those

required or permitted by law generally or by the NAD scheme in particular. The

only requirement is that the action be implementing or enforcing the NSOs own

anti–doping policy and be done in good faith.

The clear policy intent is to encourage NSO commitment to

the NAD scheme, however, the provision goes beyond the recommendation of the

Wood Review. Neither the Government Response nor the Explanatory Memorandum

contain any indication that a broader provision than recommended was thought

necessary and it may be unintentional.

Parliament may wish to consider whether:

- proposed subsection 78(5) has

been drafted too broadly and

- whether protection for NSOs and staff should be limited to acts

taken or required under the NAD scheme, rather than under the NSOs own

anti-doping policy.

Exclusion of

negligence and incompetence

It is common for statutory duties to require that duty be

exercised with reasonable care. There is no such requirement here and indeed

the protection against civil suit allows a person or organisation who carries

out a duty or function under the NAD scheme negligently or incompetently to

avoid repercussions provided they have acted in good

faith.

The ASADA Act involves

a balancing of the rights of athletes, officials and the sport itself. Given

the very serious effect an ADVR can have on an athlete’s career and reputation,

and conversely, the very serious effect undetected doping can have on the

integrity of sport; Parliament might consider whether officials acting in good faith is sufficient protection for the athlete

and sport or whether grossly negligent action should be excluded from

protection.

Part 3—Enabling

wider sharing of protected information

Part 8 of the ASADA Act

provides for the management of information that comes into the possession of

ASADA, ASDMAC or the ADRVP. Under existing subsection 67(1), it is an offence

for an entrusted person[86]

to disclose protected information[87]

except in certain circumstances or to certain bodies specified in the Act.

Existing section 67(3) provides that a court or tribunal

may not require an entrusted person to

disclose protected information. In its

current form, the Act protects only specified persons from being required to

disclose protected information to a court or tribunal. NSO personnel, however,

are not specified.

The proposed amendment to subsection 67(3) by item 45 of Schedule 1 to the Bill will apply to a person instead of only to entrusted persons. This will allow ASADA to

share protected information with NSOs because NSO personnel will have:

- the same secrecy obligations as ASADA personnel and

- the same protection as ASADA personnel against being forced to

reveal, for example, a secret source of information to a court or tribunal.

This provision implements part of Recommendation 19 of the

Wood Review. Other elements of recommendation 19 are implemented in Parts 1 and

2 of the Bill.[88]

Part 4—Lowering

the burden of proof for issue of a disclosure notice

At present, three ADRVP members

and the ASADA CEO must reasonably believe that a person has information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme before the CEO can issue a disclosure notice.[89] The power of the ASADA CEO to issue a disclosure

notice is critical to intelligence-based investigations. To be effective, the

power must be available where doping is reasonably suspected but there is no

sample analysis to support the investigation.

The Wood Review found that the present threshold of reasonably believes resulted in disclosure

notices generally only being granted by the ADRVP in circumstances where ASADA

already had evidence to suggest that an ADRV has taken place – for instance, a

returned positive sample or adverse analytical finding (AAF). [90]

The Review therefore recommended that the threshold be changed to reasonably suspects.

Neither the Wood Review nor the Explanatory Memorandum

gives a clear reason why the ASADA CEO would only issue a disclosure notice

under the present legislation where evidence of an ADRV was already available.

That is not the effect of the ASADA Act on

its face.

The ASADA Act and the

NAD scheme do not require, except in the case of medical practitioners, that

the CEO hold a reasonable belief that any person has been involved in the

commission or attempted commission of an ADRV.[91]

The threshold of reasonable belief instead applies to whether ‘the person has

information, documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of

the NAD scheme’ – not whether any person has been involved in the commission or

attempted commission of an ADRV per se.

Note that the proposed amendment to paragraph 13(1)(ea) of

the ASADA Act (at item 46 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) will not change

this position, as the threshold of reasonable suspicion does not apply to

whether an ADRV has occurred, but to whether ‘the person has information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme’. However, in proposed amendments to paragraphs 13A(1A)(a) and (b) (at item 47 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) the threshold is then

linked to an additional requirement, for medical

practitioners only, that the ASADA CEO

reasonably suspects that the person has been involved, in that capacity, in the

commission, or attempted commission, of a possible ADRV.

As Middleton J observed in Essendon

Football Club v Chief Executive Officer of the ASADA (the Essendon FC case), the responsibilities of the

ASADA CEO in administering the NAD scheme are very wide and include all the

matters in clause 1.02 of the scheme.[92]

The proposed amendments to paragraphs 13(1)(ea) and

paragraphs 13A(1A)(a) and (b) change the standard of

proof for the issue of a disclosure notice from reasonably believes to reasonably suspects.

This change in threshold, as well as the repeal in item 13 of Schedule 1

to the Bill of the need for three ADRVP members to agree with the notice,[93] will result in a significantly reduced threshold for the

issue of a coercive disclosure notice.

Non-compliance

with Attorney-General’s Department Guide to Framing Offences

The AGD Guide says that

a document disclosure provision should normally:

-

impose a threshold of ‘reasonable grounds to believe’ that a

person has custody or control of documents, information or knowledge which

would assist the administration of the legislative scheme

- give a person 14 days to comply with the notice and

- impose a maximum penalty for non-compliance of six months

imprisonment or a 30 penalty unit fine.[94]

In contrast to the above, the amendments in Part 4 propose:

- a threshold of ‘reasonable suspicion’ the person has information,

documents or things that may be relevant to the administration of the NAD

scheme

-

no limit to the period that the ASADA CEO may specify in the

notice and

- a penalty for non-compliance of 60 penalty units but no penalty of

imprisonment is applied.[95]

Where draft provisions depart from the Guide, the

AGD website instructs Departments to consult with the Criminal Law Division in

AGD before proceeding with draft provisions.[96]

The Explanatory Memorandum does not indicate that there has been such consultation

with AGD.

However, it was a Wood Review recommendation that the

threshold for issue of a disclosure notice be changed to a reasonable suspicion.

The Review said the reasonable suspicion ‘threshold for the exercise of similar

powers is relatively commonplace in comparable statutory schemes and would be

appropriate in these circumstances’ – but did not provide any such examples.[97]

In light of:

- the broad responsibilities of the ASADA CEO

- the width of the phrase ‘relevant to the administration of the

NAD scheme’ and

- the proposed provisions non-compliance with the AGD Guide

Parliament may want to examine whether a change to the

legislation is necessary, or whether a change in the ASADA CEO’s practice in

issuing disclosure notices would be sufficient.

Part 4—Removing

self-incrimination as a defence to a disclosure notice

As noted above, both the common law and the ICCPR recognise a right to not be forced to

incriminate oneself – often referred to (in a common law context) as the

privilege against self-incrimination.

Currently subsection 13D(1) of the ASADA Act provides that an individual does not

have to answer a question or give information if that might incriminate the

person or expose them to a penalty. Existing subsection 13D(2) provides

that if a person does produces a document or information, it cannot be used

against them in criminal proceedings, or proceedings that might result in a

penalty, other than proceedings for an offence against the ASADA Act or ASADA Regs, or an offence of

providing false or misleading information under the Criminal Code Act

1995.

The AOC has long opposed the privilege against

self-incrimination in this context and its President, John Coates, welcomed

Wood Review recommendations that athletes and support people be compelled to

give evidence about doping:

I am particularly pleased that the legislation establishing

the Tribunal will include ‘the power to order a witness to appear before it to

give evidence, and/or to produce documents or things; and the power to inform

itself independent of submission by the parties’.

The AOC has long argued for this legislative support to the

fight against doping in sport and, having repeatedly been knocked back,

introduced similar requirements in its Anti-Doping Policy - making it a

condition for member National Federations nominating athletes for selection in

Australian Olympic Teams that they must include these requirements in their

Anti-Doping policies...

So very much better that this be by statute rather than

relying on contractual arrangements.[98]

Proposed subsections 13D(1) and (2) (at item 50 of

Schedule 1 to the Bill) abolishes the protection against answering questions or

producing information and substitutes an amended protection against use of that

information against the person in criminal proceedings. As currently, information

provided can be used in proceedings under the ASADA

Act or the ASADA Regs (and therefore the NAD scheme), and for

prosecution for providing false or misleading information (sections 137.1 and

137.2 of the Criminal Code). The information

cannot be used in a prosecution for any other offence.

Therefore, unlike the current situation, the amendment

would allow a person to be compelled to answer questions or give information

that could then be used in evidence against them in proceedings before the NST

(for example, in relation to an alleged ADRV).

[1]. International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, done in New York on 16 December

1966, [1980] ATS 23 (entered into force for Australia (except Art. 41) on 13

November 1980; Art. 41 came into force for Australia on 28 January 1994). See

also Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (JSCFADT), Legal

foundations of religious freedom in Australia: interim report, Chapter

6, JSCFADT, Canberra, 2017.

[2]. Council

of Europe Convention on the Manipulation of Sports Competitions, opened for

signature 18 September 2014, CETS No. 215 (not yet in force); Council of

Europe, Treaty Office website, Chart

of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 215.

[3]. J

Wood, D Howman and R Murrihy, Report

of the review of Australia’s sports integrity arrangements, (Wood

Review), Department of Health, Canberra, 1 August 2018.

[4]. Department

of Health, Safeguarding

the integrity of sport—the Government response to the Wood Review,

(Government Response), Department of Health, Canberra, 12 February 2019, p. 3.

[5]. Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Act 2006, section 10.

[6]. Ibid.,

section 21.

[7]. Ibid.,

Parts 5 and 7 respectively.

[8]. Ibid.,

section 41.

[9]. Australian Sports Anti‑Doping

Authority Regulations 2006, clauses 1.03A, 4.08 and 4.09 of Schedule

1.

[10]. World

Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), ‘The

Agency’s History’, WADA website.

[11]. World

Anti-Doping Code 2015. Some 2017 amendments to the Code took effect on 1

April 2018 and are included in the 2015 version.

[12]. World

Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), ‘The Code’, WADA

website.

[13]. R

Jolly, Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Bill 2014, Bills digest, 25,

Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 10 September 2014, p. 4.

[14]. D

Thorpe, A Buti, C Davies and P Jonson, Sports law, 3rd edn, South

Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 413

[15]. ASADA

Act, section 9.

[16]. ASADA

Regs, subclauses 1.06(1) and (1A).

[17]. Ibid.,

pp. 411–412, 415.

[18]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 209.

[19]. Department

of Health ‘Consultation

Hub: Review of Australia’s sports integrity arrangements – developing a Government

response,’ Department of Health website.

[20]. Government

Response, recommendation number 38, op. cit., p. 19. B McKenzie (Minister for

Sport), Strengthening

integrity in Australian sport, media release, 14 February 2019. B

McKenzie (Minister for Sport) and P Dutton (Minister for Home Affairs), Protecting

the integrity of sport, media release, 12 February 2019.

[21]. AOC,

AOC

welcomes integrity review and national sports plan, media release, 1

August 2018.

[22]. Wood

Review, recommendation 17, op. cit., p. 111.

[23]. Government

Response, op. cit., p. 12.

[24]. Ibid.

[25]. Government

Response, op. cit., p. 3.

[26]. Wood

Review, op. cit., pp. 102–139.

[27]. Government

Response, op. cit., p. 9.

[28]. Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny digest, 2, 2019, The Senate,

Canberra, 28 March 2019, pp. 10–13.

[29]. Sen

D Farrell (Shadow Minister for Sport), Sports

game plan a start but proof is in performance, media release,

1 August 2018.

[30]. ASADA,

ASADA

fully endorses the Federal Government’s sport integrity plan, media

release, 12 February 2019.

[31]. AOC,

AOC

welcomes integrity review and national sports plan, media release, 1

August 2018.

[32]. AOC,

AOC

commends government response to the Wood Review, media release, 12

February 2019.

[33]. Paralympics

Australia, Paralympics

Australia supports new integrity measures to safeguard Australian sport, media release, 13 February 2019.

[34]. M

Speed, Submission

to Review Panel on Australia’s Sports Integrity Arrangements, The Coalition

of Major Professional & Participation Sports Inc. (COMPPS), 2 October 2017,

p. 6. P Sakkal, Sports

spurn new national integrity body, The Age,

16 February 2019, p. 2.

[35]. COMPPS,

submission, op. cit., p. 8.

[36]. COMPPS,

submission, pp. 8–9.

[37]. Exercise

and Sports Science Australia (ESSA), ‘Review

of Australia's Sports Integrity Arrangements - Developing a Government Response’,

ESSA website.

[38]. Australian

Athletes Alliance (AAA), ‘Who

we are’, AAA website.

[39]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 110, citing Submission 25.

[40]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 110.

[41]. Thorpe,

et al, op. cit., pp. 411–412; citing the World Anti-Doping Code 2015, ‘Purpose

Scope and Organisation of the World Anti-Doping Program and the Code,’

p. 11.

[42]. Commonwealth

Games Australia, Integrity

initiatives welcomed by Commonwealth Games Australia, media release,

12 February 2019.

[43]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority

Amendment (Enhancing Australia's Anti-Doping Capability) Bill 2019, p. 1.

[44]. COMPPS,

submission, pp. 6, 8–9. AOC, AOC

commends government response to the Wood Review, media release,

12 February 2019.

[45]. Commonwealth

Games Australia, op. cit.

[46]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at page 2 of the

Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill.

[47]. Attorney-General’s

Department (AGD), ‘Presumption

of innocence’, AGD website.

[48]. Australian

Law Reform Commission (ALRC), Traditional

rights and freedoms—encroachments by Commonwealth laws, ALRC report,

129, December 2015, Chapter 11 generally.

[49]. AGD, A guide

to framing Commonwealth offences, infringement notices and enforcement powers,

AGD, Canberra, September 2011, p. 90.

[50]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 104.

[51]. Anti-Doping

Convention, done in Strasbourg, 16 November 1989, [1994]

ATS 33 (entered into force for Australia 1 December 1994).

[52]. International

Convention Against Doping in Sport, done at Paris 19 October 2005, [2007]

ATS 10 (entered into force generally and for Australia 1 February 2007).

[53]. Constitution,

section 51(xxix).

[54]. For

example, it a condition of recognition by the International Olympic Committee

that International Federations within the Olympic Movement are in compliance

with the Code. See Thorpe et al, op. cit., p. 412.

[55]. Thorpe

et al, Sports law, pp. 412–413.

[56]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 214.

[57]. SportAUS,

2014-2018

National Sporting Organisation Recognition Criteria, n.d. para. 6. The

policy is currently under review. A March 2019 draft policy retains the

requirement: SportAUS, 4.2

- DRAFT 2019-23 NSO/NSOD Recognition, Attachment A, 2019-23 NSO/NSOD

Recognition Criteria, n.d. para. 7.

[58]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 214.

[59]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 109.

[60]. Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Act 2009.

[61]. R

Jolly, Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Bill 2009, Bills digest, 41,

2009–10, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, pp. 4–5.

[62]. N

Jeffery, ‘Flaws

in anti-doping body: Coates’, The Australian, 13 January 2006, p. 3.

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Act 2009.

[65]. R

Jolly, Australian

Sports Anti-Doping Authority Amendment Bill 2009, Bills digest, 41,

2009–10, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, p. 9.

[66]. AOC

media releases, op. cit.

[67]. Wood

Review, op. cit., pp. 133–134.

[68]. Wood

Review, Chapter 4, Key finding 8, op. cit., p. 105.

[69]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 131.

[70]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 132.

[71]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 145.

[72]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 110, 144, 146.

[73]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 134.

[74]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 136.

[75]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 133.

[76]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 132.

[77]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 133.

[78]. Wood

Review, op. cit., pp. 134–135, recommendation 24.

[79]. Wood

Review, op. cit., pp. 131, 134.

[80]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 133.

[81]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 14, 152, 157, 161 and 162; recommendation 35.

[82]. See

clauses 4.11, 4.12, 4.17 and 4.22 of Schedule 1 to the Australian Sports

Anti-Doping Authority Regulations 2006.

[83]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 137.

[84]. Section

78 of the ASADA Act.

[85]. Wood

Review, recommendation 19, op. cit., pp. 113, 115.

[86]. Defined

in ASADA Act, section 69.

[87]. Defined

in ASADA Act, section 4.

[88]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 115.

[89]. ASADA

Act, subsection 13A(1A).

[90]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 129.

[91]. ASADA

Act, subsection 13A(1A). The ASADA Act provisions are repeated in

the NAD Scheme at clauses 3.26A and 3.26B in Schedule 1 to the ASADA Regs.

[92]. Essendon

Football Club v Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping

Authority (2014) 227 FCR 1, [2014] FCA 1019,

at para. [377].

[93]. Existing

paragraph 13A(1)(c) of the ASADA Act.

[94]. AGD,

A

guide to framing commonwealth offences, op. cit., pp. 90–93.

[95]. Item

49 of Schedule 1 to the Bill increases the maximum penalty available to 60

penalty units.

[96]. AGD,

A

guide to framing commonwealth offences, op. cit., p. 8.

[97]. Wood

Review, op. cit., p. 129.

[98]. AOC,

media release, 1 August 2018, op. cit.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.