Bills Digest No. 96, 2017–18

PDF version [3MB]

Dr Hazel Ferguson

Social Policy Section

26 March 2018

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Background

Income contingent student loan

programs

Higher Education Loan Program

Figure 1: Total outstanding Higher

Education Loan Program debt, 2010–11 to 2015–16 ($m)

Figure 2: Higher Education Loan

Program total estimated outstanding debt, 2016–17 to 2020–21 ($m)

Figure 3: Higher Education Loan

Program proportion of debtors by size of debt, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Student Start-up Loans

Trade Support Loans

Student Financial Supplement Scheme

Figure 4: SFSS total estimated

outstanding debt, 2016–17 to 2020–21, at 2017–18 Budget ($m)

The sustainability of student loan

programs

Committee consideration

Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

The HELP minimum repayment threshold

The lifetime HELP borrowing limit

Other issues

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Changes to repayment thresholds and

indexation

Changes to repayment thresholds and

rates under HESA

Changes to SFSS repayment thresholds

Table 2: 2017–18 repayment income

thresholds and rates for SFSS and proposed transitional arrangements for

2018–19

Changes to indexation under HESA

Changes to order of repayment of

debts

Introduction of a combined HELP loan

limit

Concluding comments

Appendix 1: Average Weekly Earnings

(AWOTE), HELP repayment rates and thresholds: 1988–89 to 2016–17

Date introduced: 14 February 2018

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Education and Training

Commencement: At various dates, as set out in the digest.

Links: The links to the Bill, its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the Bill’s home page, or through the Australian Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as at March 2018.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Higher Education Support Legislation

Amendment (Student Loan Sustainability) Bill 2018 (the Bill) is to amend the Higher Education

Support Act 2003 (HESA), to:

- revise

the Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) repayment thresholds and rates,

including introducing a lower minimum repayment threshold of $45,000 per annum with

a repayment rate of one per cent

- introduce

a combined lifetime HELP loan limit, across all HELP loans for course fees, of

$150,000 for students studying medicine, dentistry and veterinary science

courses, or $104,440 for all other students that is indexed to the Consumer

Price Index (CPI) and

- change

the indexation factor for HELP repayment thresholds from Average Weekly

Earnings (AWE) to the CPI.[1]

The Bill also:

- proposes

to amend the Social

Security Act 1991, Student Assistance

Act 1973 and Trade

Support Loans Act 2014 to add Student Financial Supplement Scheme

(SFSS) debts to the repayment arrangements already in place for other

student loan programs, ensuring SFSS debts are no longer repaid concurrently

with HELP, Student Start-up Loan (SSL) and Trade Support Loan (TSL) debts, and

a single, shared set of repayment thresholds and rates are applied across the

four programs and

- proposes

consequential amendments to the VET Student Loans

Act 2016 to include Vocational Education and Training (VET) Student

Loans in the HELP loan limit.[2]

Background

Income

contingent student loan programs

Student loan programs have proliferated since their

introduction in the form of the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) in

1989, and are now administered in the Education and Training, Human Services, and

Social Services portfolios.

While these programs are all income contingent, meaning

they are repaid through the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) only when a

debtor’s income is more than the minimum repayment threshold, they are

distinguished by their purpose, repayment arrangements, and the fees, discounts

and caps applied under some programs. This section briefly sets out these key

features for each student loan program.

Higher

Education Loan Program

The largest of the student loan programs, HELP, in the

Education and Training portfolio, is comprised of four sub-schemes and VET

Student Loans, which replaced VET FEE-HELP from 1 January 2017.[3]

HELP debt is repaid first if debtors owe under multiple programs, and a four per

cent minimum repayment rate applies from the minimum repayment threshold of $55,874

in 2017–18 (see Table 1 below for the full list of current repayment thresholds

and rates).[4]

From 1 July 2018, a lower repayment rate of two per cent will apply at a new minimum

repayment threshold of $51,957.[5]

HECS-HELP, which replaced HECS in 2005, is available for

Commonwealth supported higher education students (typically domestic

undergraduate students studying at Australian public universities) to pay their

student contribution amounts—the part of the course fee not paid by the

Commonwealth.[6]

According to the Department of Education and Training (DET), ‘[i]n 2015 and

2016, 88 per cent of Commonwealth supported students deferred their

payment through HECS-HELP.[7]

FEE-HELP is available for domestic full fee-paying higher

education students to pay course fees up to a lifetime FEE-HELP borrowing limit

of $127,992 for medicine, dentistry and veterinary science students and $102,392

for other students.[8]

In 2016, 77,778 FEE-HELP loans were issued.[9]

A 25 per cent loan fee is added to the balance of the loan when FEE-HELP is

used for undergraduate study.[10]

In 2016, the equivalent of approximately 28,050 full-time students deferred tuition

costs through FEE-HELP for courses where the loan fee would apply.[11]

SA-HELP is available to students wishing to defer payment of

the student services and amenities fee, which higher education providers charge

for non-academic student services and amenities such as counselling services.[12]

The 2018 fee is capped at $298 per student, with those studying part-time

charged up to 75 per cent of the full-time fee.[13]

483,803 SA-HELP loans were issued in 2016.[14]

OS-HELP is available for eligible Commonwealth-supported higher

education students undertaking part of their course overseas. Unlike other HELP

loans, OS-HELP is paid to the student (rather than the higher education

provider, which is the case for the other schemes) and can be used for living

costs, including airfares and accommodation.[15]

Students must be approved for the loan by their higher education provider, may

take out only two OS-HELP loans—each to be expended for a six-month study period—over

the course of their studies, and can borrow only up to a set cap, which is $6,665

(if not studying in Asia) or $7,998 (if studying in Asia) in 2018.[16]

14,861 OS-HELP loans were issued in 2016.[17]

OS-HELP was introduced with a 20 per cent fee, however this was removed in

2009.[18]

Introduced in 2007 for study from 2008, VET FEE-HELP was

replaced by VET Student Loans from 1 January 2017.[19]

VET Student Loans are available to VET students studying an approved course at

an approved training provider, to defer their course costs.[20]

The FEE-HELP lifetime borrowing limit also applies to and includes VET Student

Loans, meaning borrowings under both loans contribute to the total available

balance.[21]

Like FEE-HELP, a loan fee also applies to VET Student Loans—a 20 per cent fee

is applied unless the student is enrolled in a place that is subsidised by

their state or territory government.[22]

Although the lifetime borrowing limit and loan fee applied to borrowings under

VET FEE-HELP, the introduction of VET Student Loans also saw the introduction

of course borrowing limits in response to rapidly increasing debt.[23]

In 2017, course borrowing limits of $5,000, $10,000 and $15,000 applied depending

on the course, with a $75,000 limit available for specified aviation courses.[24]

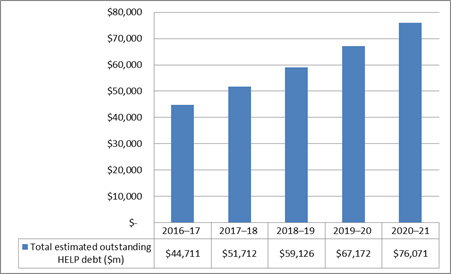

The size of the HELP loan portfolio has grown

substantially in recent years (Figure 1 below). The most recent available forward estimates

for HELP, shown in Figure 2 below, project the total HELP debt owing will reach

approximately $75 billion by 2020–21.[25]

At 30 June 2017, the estimated the proportion of debt not expected to be repaid

(DNER) was 25 per cent.[26]

However, this estimate drops to 18 per cent if VET loans are not included.[27]

Figure 1: Total outstanding Higher Education Loan Program debt, 2010–11 to

2015–16 ($m)

Source: Australian Tax Office

(ATO), Taxation Statistics 2014–15, ‘Summary – Table 5’, 2017.

Figure 2: Higher Education Loan Program total estimated outstanding debt,

2016–17 to 2020–21 ($m)

Source: Australian Government, ‘Statement

10: Australian Government financial budget statements’, 2017–18 Budget:

Budget paper no. 1: 2017–18, p. 29.

Notes: 2017–18 Budget forward estimates were based on policy

settings at May 2017, which included measures from the Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (A More Sustainable, Responsive and

Transparent Higher Education System) Bill 2017, which have since been

replaced by the 2017–18 mid-year economic and fiscal outlook

‘Higher Education Reforms—revised implementation’ measure.[28]

Growth in the overall size of the HELP loan portfolio is

also reflected in the rising average outstanding debt ($20,300 in 2016–17) and

time to repay (8.9 years in 2016–17).[29]

However, as shown in Figure 3 below, the proportion of debtors owing

above $30,000 is, while rising, still below 20 per cent.

Figure 3: Higher Education Loan Program proportion of debtors by size of debt,

2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: Australian Tax Office (ATO), Taxation

Statistics 2014–15, ‘Summary – Table 5’, op. cit.

Student Start-up

Loans

The SSL, administered in the Human Services portfolio,

replaced the Student Start-up Scholarship from 1 July 2017.[30]

According to the Department of Social Services (DSS), ‘[t]he SSL aims to

increase participation in higher education by assisting students with the costs

of commencing study, including the purchase of text books, computers and

internet access.’[31]

The SSL is available to eligible higher education students receiving Youth

Allowance (student), Austudy or ABSTUDY Living Allowance in addition to their

income support payments.[32]

At 1 January 2018, $1,055 can be paid to approved students twice per

year, generally at the beginning of each semester.[33]

For SSL debtors who also have debt under other programs, SSL debt is repaid

second (after HELP is fully repaid), and shares the same repayment threshold

and rates as HELP (see Table 1 below for the full list of current

repayment thresholds and rates).[34]

Trade

Support Loans

According to DET, ‘[t]he Trade Support Loans (TSL) program,

which commenced in July 2014, aims to increase completion rates among

Australian Apprentices in priority areas by providing financial support to

assist them with the costs of living and learning while undertaking an

apprenticeship.’[35]

Similar to the SSL and OS-HELP, the TSL is paid directly to the apprentice, and

can be spent on everyday costs.[36]

The TSL provides up to a $20,420 lifetime limit (indexed annually on 1 July) for

eligible apprentices completing a qualification on the Trade Support Loans

Priority List 2014.[37]

Apprentices opt in for six monthly periods, and receive monthly payments. The

amount available in each six-monthly period decreases over the four-year term

of a typical apprenticeship, from up to $8,168 in the first year, to up to $2,042

in the fourth year. Once the apprenticeship is complete, a 20% discount is

applied to the outstanding TSL debt. Repayments are made according to the same

arrangements as HELP and the SSL, outlined in Table 1 below, and TSL

debt repaid third if debtors owe under the other programs.[38]

The first evaluation of the TSL is due to be completed in 2017–18.[39]

Student

Financial Supplement Scheme

The SFSS was first introduced in January 1993 as the

AUSTUDY/ABSTUDY Supplement, and operated under that name until the introduction

of Youth Allowance in July 1998, at which time it moved from the education

portfolio into the then Department of Family and Community Services, and

renamed the SFSS.[40]

The SFSS operated until 31 December 2003, and outstanding debts continue to be administered

in the Social Services portfolio and collected through the tax system under

arrangements similar to that for HELP, SSL and TSL.[41]

Under the SFSS scheme as it operated just before its closure, eligible tertiary

students could trade in all or part of their student income support payment for

twice the amount in the form of a loan.[42]

For example, a student trading in $100 of their income

support payment would receive $200 for everyday expenses, and $200 would be

recorded as an SFSS debt. In explaining the scheme’s closure, then Minister for

Children and Youth Affairs, Larry Anthony, said the loan was a ‘debt trap’,

which had resulted in high levels of debt among the poorest students, and high

rates of debt not expected to be repaid (DNER).[43]

At the time, an unpublished report from the Australian Government Actuary (AGA)

put SFSS DNER at fifty per cent.[44]

Unlike other student loan debts, SFSS has specific repayment thresholds and

rates, and is repaid concurrently with other loans listed above, as

outlined in Table 2 below.

According to the 2017–18 Budget papers, total estimated

outstanding SFSS debt in 2016–17 was $367 million, but projected to be

less than half this in 2020–21 (Figure 4 below).

Figure 4: SFSS

total estimated outstanding debt, 2016–17 to 2020–21, at 2017–18 Budget ($m)

Source: Australian Government, ‘Statement

10: Australian Government financial budget statements’, op. cit., pp.

10–29.

The

sustainability of student loan programs

The key measures in this Bill (the lower minimum HELP

repayment threshold and rate, and HELP borrowing limit) were announced in the Mid-year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2017–18 (MYEFO).[45]

The MYEFO ‘Higher Education Reforms—revised implementation’ measure replaces

the previous unlegislated higher education reform measures from the 2017–18

Budget, which had been brought forward in the Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (A More Sustainable, Responsive and

Transparent Higher Education System) Bill 2017 (the HESLA Bill).[46]

In turn, the HESLA Bill was a post- consultation replacement for the

unsuccessful Higher

Education and Research Reform Bill 2014, an amended version of the Higher

Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill 2014, which proposed to

legislate the far-reaching 2014–15 Budget higher education reform announcements,

including the deregulation of undergraduate higher education fees, an average

20 per cent cut to funding through the Commonwealth Grant Scheme (CGS), a real

interest rate for HELP debts and a lower income threshold for repayment.[47]

This Bill is more narrowly focused than its predecessors

partly because the other key elements of the MYEFO higher education reform

announcements, that CGS funding for 2018 and 2019 would be frozen at 2017

levels, and future funding growth from 2020 would be linked to performance

targets, could be achieved without legislation.[48] However, it continues the

framing of higher education funding in terms of sustainability. One DET

fact sheet about the current reform package explains:

These reforms are necessary to ensure Australia’s generous,

income-contingent loan system remains sustainable so future generations of

Australians, regardless of their background or their financial means, can

continue to access higher education without upfront fees.

Outstanding HELP loans now total more than $50 billion, and

if reform is not pursued around a quarter of new debts are not expected to be

repaid. Some students have borrowed excessively against the student loan

schemes and amassed more debt than can be repaid during their working life.[49]

While there is no agreed definition of ‘sustainability’ in

respect to student loans, according to DET’s performance criteria, HELP loans

should be ‘affordable for both students and the community’.[50] For the community (via

the Commonwealth), outstanding HELP debt is a financial asset on the

balance sheet which incurs costs in two ways:

- as

there is no interest paid on the debt and the debt is indexed to inflation (which

is usually lower than the Commonwealth’s borrowing costs) there is an implicit

subsidy consisting of the difference between borrowing costs and what the

debtor pays and

- some

‘doubtful’ HELP debt is never repaid due to death of the debtor or the income

threshold for repayment not being met.[51]

The key consideration in proposals to improve the

sustainability of HELP is therefore balancing measures to recover or avoid these

costs with the expectations of students, prospective students, their parents,

and higher education providers, who are concerned with access to education and

repayment affordability.

Some lending costs are currently recovered through the FEE-HELP,

VET FEE‑HELP, and VET Student Loans loan fees discussed in the

previous section. Analysis in a higher education context suggests that when

individual HELP debt levels are low, as is the case for most HECS-HELP debt

where fees are capped, then the subsidy is low, but when individual debt levels

are high, such as in the upper limits of FEE-HELP debt, then taxpayer subsidies

range from 20 to 30 per cent—hence the fees are applied to loans which risk

higher subsidies, rather than across all HELP loans.[52]

The 2008 Review of Australian Higher Education chaired by Professor Bradley

(the Bradley review) reiterated that the FEE-HELP loan fee was ‘intended to

recover some of the costs to the Commonwealth associated with the repayment

subsidies.’[53]

However, because the design of HELP does not include any

credit risk management akin to commercial credit arrangements, loan fees

essentially transfer the risk of non-payment from government to the individuals

who do repay their debt. Mark Warburton, Honorary Senior Fellow at the LH

Martin Institute, argues:

There is a policy intention/objective that some people will

not be required to repay their loan. This is in stark contrast to the usual

arrangements of lending financial institutions where the objective is that all

of a loan and all of its interest is repaid.[54]

When a student has a combined debt in different categories, targeted

cost recovery through existing loan fees also appears to be less appropriate:

Students who go onto FEE-HELP courses while they still have a

HECS-HELP debt will have larger overall HELP debts than students who just do

one undergraduate FEE-HELP course... the surcharge should be adjusted to the

total existing HELP debt, rather than being based on undergraduate/postgraduate

distinctions that entrench unfair anomalies in the system.[55]

Additionally, since borrowing for each course paid for through

VET Student Loans is capped, the modelling of subsidies based on the FEE-HELP

borrowing limit is less likely to apply to newer borrowers undertaking VET

qualifications.

However, alternatives such as the proposal in the unsuccessful

Higher

Education and Research Reform Amendment Bill 2014 to abolish the FEE-HELP

loan fee and change HELP debt indexation from CPI to the 10-year government

bond rate, capped at six per cent, also have inequitable outcomes.[56]

Analysis of the 2014 bond rate proposal suggested a higher indexation rate

would have a disproportionate impact on lower income professions such as

teaching and nursing, and would have a greater impact on women across all

professions, with debts continuing to grow in real terms during times outside

the workforce.[57]

To resolve these tensions, the Grattan Institute’s Andrew

Norton and Ittima Cherastidtham have proposed a 15 per

cent loan fee across all HELP loans to equalise government cost recovery across

loan schemes.[58] Bruce Chapman, one of the designers of HECS,

has also supported this proposal.[59]

Nevertheless, recently legislated changes to improve the

sustainability of HELP have focused on reducing the amount of unpaid HELP debt.

Recent changes include the lower repayment rate of two per cent and minimum

repayment threshold of $51,957 due to commence from 1 July 2018, and HELP

repayments for overseas debtors which commenced 1 July 2017.[60]

The question of how best to recover the lending costs associated with HELP is

not directly addressed in this Bill.

Committee consideration

Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee

The Bill was referred to the Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee. The Committee reported on 16 March 2018, recommending

that the Government ‘consider amending schedule 3 of the [B]ill to introduce a

cap on outstanding HELP debts, rather than a lifetime loan limit’, but

otherwise pass the Bill.[61]

Details of the inquiry are available from the inquiry

homepage.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee

for the Scrutiny of Bills had no comment on the Bill.[62]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The Labor

Senators' Dissenting Report in the Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee report on the Bill recommends the Bill not be supported,

and states ‘Labor Senators oppose the Higher Education Support Legislation

Amendment (Student Loan Sustainability) Bill 2018... Labor believes the changes

to HELP repayment thresholds are simply driven by budget cuts.’[63]

During her speech to the Universities Australia (UA) conference

on 1 March 2018, Labor’s Shadow Minister for Education and Training, Tanya

Plibersek, spoke against the higher education savings measures announced in MYEFO.[64]

The speech also detailed plans for National Inquiry into the architecture of

post-secondary education to inform policy approaches, if Labor is elected to

government.[65]

The Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) welcomed the announcement of

the proposed National Inquiry, which reflects the NXT commitment to a ‘comprehensive

review [of post-secondary education], akin to the Gonski-led review of

education.’[66]

The Greens’ higher education spokesperson, Senator Sarah

Hanson-Young, also responded to the MYEFO announcements by focusing on the impact

of the funding freeze on Commonwealth supported places (which did not need to

be legislated) stating ‘the Government must guarantee that all students offered

a place at university will have their study funded, following billions of

dollars in cuts that puts at risk 10,000 places this year alone, according to

Universities Australia.’[67]

The Australian

Greens Senators' Dissenting Report also recommends the Senate oppose

the Bill.[68]

Position of

major interest groups

The HELP

minimum repayment threshold

A number of submissions to the Senate Committee Inquiry

raise concerns about the possible impact of a lower HELP minimum repayment

threshold on access to higher education and graduate living conditions.[69]

The National Union of Students and Council of Australian Postgraduate

Associations have collaborated on a campaign called Bury the Bill to

oppose the Bill, stating it ‘condemns lower-earning graduates to pay back their

student loans when barely earning minimum wage.’[70]

UA argues that HELP repayment should begin at around

average earnings.[71]

The Australian Council of Deans of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (DASSH)

argues the measure will have a disproportionate impact on graduates of

humanities, arts and social science courses, who often take longer to establish

their careers and are more likely to be women, resulting in periods of lower

earnings.[72]

In contrast, the Grattan Institute argues that HELP

repayment arrangements should be more closely aligned with protections in place

to prevent and alleviate poverty, rather than average wages:

Although the high threshold was politically understandable in

the late 1980s, it is anomalous within the broader Australian income protection

system. A lower initial threshold would bring HELP more into line with other

forms of income protection for working-age adults ...

Using the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia

(HILDA) survey, Grattan previously estimated the effect of lowering the initial

threshold from about $56,000 to $42,000 and found that about half of debtors

who would start repaying have a partner. Nearly a third of those with a partner

have a combined disposable household income of at least $100,000 and nearly

three quarters have household disposable incomes of at least $80,000. [73]

The

lifetime HELP borrowing limit

The possible impacts of the combined lifetime HELP

borrowing limit are addressed in a number of submissions. The University of

Canberra stated it:

... strongly supports the encouragement of lifelong learning in

order to meet the changing demands of the world of work. The university does

not agree that there should be a limit on student loans for education.[74]

EPHEA suggests the limit ‘may impact negatively on

students who incurred a VET student debt as a pathway to higher education. In

addition, the method of determining the loan limit is not explained, and may

have implications for students accessing Start-up loans.’[75]

Likewise, Science and Technology Australia raises concerns about the impact on

those entering university from VET pathways and then undertaking further

training to become teachers, especially in science, technology, engineering and

mathematics.[76]

Bond University (Bond), a private not-for-profit

institution whose domestic students would generally be eligible to defer their

course costs through FEE-HELP but not HECS-HELP, is particularly concerned

about the impact of the limit:

Bond University strongly advocates for a system which

supports life-long learning. We also understand the need for policy settings

that are fiscally responsible and sustainable, and we accept that cap on the

total loan value provides a viable way of mitigating the risk of ballooning

debt. We propose a refreshable loan as a responsible balance between these two

objectives. Students who have accessed HELP loans repaid

their debt, in part or in full, should be able to access the scheme again to

fund further study so long as their outstanding debt does not exceed the loan

cap. [77]

The University of Melbourne, which under the ‘Melbourne

model’ offers more generalist undergraduate degrees with professional

specialisations at postgraduate level, likewise recommends against the limit,

and proposes if adopted the Senate consider amendments including a higher borrowing

limit, exceptions for long term unemployed or primary carers of children

returning to work, and the option of refreshing the limit by making debt

repayments.[78]

Other

issues

Bond also raises the issue of loans fees, which as

discussed earlier in this digest only apply to some loans under the FEE-HELP

and VET Student Loans (and previously VET FEE-HELP) loans. Bond argues ‘[t]he

harmonisation of HELP schemes proposed by this legislation needs to go one step

further to set equal terms for the student borrowers by introducing a

consistent approach to loan fees’.[79]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill:

- changes

to HELP repayment thresholds and indexation will deliver savings of $345.8

million from 2017–18 to 2020–21

- changes

to SFSS repayment thresholds and order of repayment of debts will have nil

fiscal balance impact and

- the

introduction of the combined HELP loan limit will cost $22.9 million from

2017–18 to 2020–21.[80]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[81]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Bill had not been considered

by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights.

Key issues

and provisions

Changes to repayment

thresholds and indexation

As discussed above, for the 2017–18 financial year, HELP,

SSL, TSL and SFSS debtors must begin making repayments through the tax system

once their income reaches $55,874 per annum, although apart from this

commonality, SFSS-specific repayment thresholds and rates currently apply. New

HELP, SSL and TSL thresholds and repayment rates, due to commence 1 July 2018 for

the 2018–19 financial year, were given effect by the Budget Savings

(Omnibus) Act 2016.

Schedule 1 proposes changes to repayment thresholds

and rates for all four loan programs including a lower minimum repayment

threshold of $45,000 per annum with a repayment rate of one per cent,

commencing 1 July 2018 for the 2018–19 income year, with SFSS

repayment arrangements proposed to come under HESA from 2019–20. It also

proposes to change how the repayment thresholds are indexed.

While the appropriate level for repayments to begin is in

some respects always open to debate, one consequence of the proliferation of

loans programs is a debtor population with weaker earnings potential than was

anticipated in the original design of HECS, meaning higher repayment thresholds

pose a greater risk of unpaid debt.[82]

In particular, in light of the introduction and expansion

of VET FEE-HELP, now VET Student Loans, the Australian literature on

educational attainment and earnings consistently shows higher lifetime earnings

among higher education graduates compared with those with vocational

post-school qualifications. For example, a report prepared by National Centre

for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) using data from the 2009–10

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Survey of Income and Housing

Confidentialised Unit Record File shows a Bachelor degree holder was likely to

earn around $2.9 million over their lifetime (in 2010 dollars) compared with

$2.1 million for a person with Year 12 or Certificate qualifications, and $2.4

million for someone with a Diploma.[83]

According to the ABS, in 2017, median weekly earnings stood at $1,035 for

people with a Certificate III or IV, $1,026 for people with an Advanced Diploma

or Diploma, and $1,280 for those with a bachelor degree.[84]

However, the tighter controls on lending introduced with VET Student Loans may

already be going some way toward addressing the higher risk of HELP loans for

VET qualifications.[85]

The latest graduate employment outcomes from DET’s Quality

Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) shows that in 2017, 71.8 per cent

of undergraduate, 80.4 percent of postgraduate research graduates, and 86.1 per cent

of postgraduate coursework graduates were in full-time employment four months

after completing their degree.[86]

19.7 per cent of undergraduates were in part time employment and seeking more

hours, although the majority of these were seeking more hours because they were

still studying.[87]

The median starting salary for the full-time employed graduates was 60,000 for

undergraduates, 81,000 for postgraduate coursework graduates, and 87,800 for

postgraduate research graduates.[88]

Despite this, even among bachelor degree holders the

lifetime earnings premium varies by gender and field of education. Medicine,

law and dentistry graduates achieve substantially higher earnings premiums than

those with humanities, agriculture and performing arts degrees.[89]

Meanwhile, a median male bachelor degree holder has lifetime additional

earnings of $1.4 million, compared with $1 million for the median female

bachelor-degree holder.[90]

While there is limited research on the labour market outcomes of graduates from

disadvantaged backgrounds in Australia, available analysis suggests that for

some groups—namely graduates from non-English speaking backgrounds and female

graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics

fields—disadvantages persist in the labour market.[91]

As such, since introduction of HECS, efforts to recover

government costs by increasing students’ costs—either by increasing fees or

changing repayment arrangements—have been a recurring concern. However, the

evidence that students are dissuaded from study by less generous payment

arrangements is mixed.

In 2002, Chapman and Ryan surveyed the research literature

and analysed data from the Youth in Transition Survey, and concluded that the

introduction of HECS (which introduced student contributions where government

had previously paid the full cost) did not adversely affect participation.[92]

For students from low socio-economic (SES) backgrounds, 2009 research suggested

factors relating to leveraging school performance for university entry may be

of more consequence and ‘policy interventions that rectify the credit

constraint problem that faces individuals at the time they make university

entrance decisions are not sufficient to equalize university participation

across social groups’.[93]

However, 2011 analysis by Deloitte Access Economics for

the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations found

modest reductions in demand, measured by number of applications, among low SES

students, and people aged 21 and over, directly following some previous

HECS/HELP policy changes, as well as some inconsistent effects by field of education.[94]

However, participation rates have continued to increase over the longer term,

suggesting these effects may be relatively short lived.[95]

If the overriding policy aim of HELP is to increase access

to tertiary education, debt write-down is a necessary feature to achieve the

social policy goals of the program. However, if reducing government costs is

the overriding concern, then it is notable that payment arrangements for HELP

are much more generous than those applied in some other social policy areas.

Andrew Norton outlines:

If risk management is HELP’s core function, fairness

considerations suggest that a lower threshold is needed. Students should expect

to repay their debts, except when they experience financial hardship. The

threshold should not be set with reference to average weekly earnings, but

should instead use benchmarks of low income. While some social security

benefits are arguably too low, threshold reform should aim for greater

alignment among government income protection programs.[96]

Changes to

repayment thresholds and rates under HESA

As set out in Table 1 below, part 1, item 1 proposes

to replace the minimum repayment income at paragraph 154–10(a) of the HESA

with an amount of $44,999 for the 2018–19 income year. Item 2 proposes

to repeal and replace the table at section 154–20 of HESA, which sets

out repayment income thresholds and rates.

As can be seen in the table, the new arrangements add to

those due to commence 1 July 2018 to create a more gradual transition from nil

to four per cent repayments, requiring repayments to begin at lower incomes and

avoiding the ‘cliff’ currently in place at four per cent, where someone earning

$55,874 in 2017–18 makes no repayment, but someone earning $55,875 pays four

per cent of their total income, or $2,235, unless they qualify for an

exemption. The DET submission to the Senate Committee Inquiry into the Bill

makes the point that under these arrangements there appears to be ‘a group of

debtors with their reported income just below the current minimum repayment

threshold. This suggests that the current repayment rates create incentives for

some debtors to minimise their reported HELP repayment income to deliberately

avoid repayments.’[97]

However, in recent years the CPI indexation rate applied to outstanding

HELP, SSL, TSL and SFSS debts that are at least 11 months old on 1 June each

year has varied between 3.0 per cent and 1.5 per cent.[98]

This means repayments at the lower end of the proposed rates are likely to fall

below indexation growth, with debtors continuing to see their HELP balance grow

even as they make repayments.

Additionally, the proposed changes would see some repaying debtors

move between repayment rates. Currently, someone earning $60,000, the median

starting salary for a full-time employed graduate from an undergraduate degree

in 2017, would repay 4.0 per cent in 2017–18, and remain at that rate in 2018–19.[99]

Under the proposed changes, they would move down to a 3.0 per cent repayment

rate in 2018–19.

At higher incomes, a number of new thresholds apply. In 2017–18,

an eight per cent repayment rate applies to incomes of $103,766 and above. In 2018–19,

the eight per cent rate will apply to incomes of $107,214 and above. Under the

proposed changes, eight per cent will apply from $104,548 to $110,820, with new

rates at 0.5 per cent increments up to 10 per cent for incomes of $131,989

and above.

However, at a minimum repayment threshold of $45,000 for

2018–19, exemptions under section 154–1 of HESA, which

exempts debtors from making repayments if, under section 8 of

the Medicare

Levy Act 1986, they do not have to pay the full Medicare Levy, would

likely apply to more people.[100]

According to the ATO:

In 2016–17 your Medicare levy is reduced if your family

taxable income is equal to or less than $45,676 ($59,587 if you are entitled to

the seniors and pensioners tax offset) plus $4,195 for each dependent child you

have.[101]

Therefore, under current arrangements and at 2016–17

rates, a family with three children (and not entitled to the seniors and

pensioners tax offset) would not make HELP repayments until their family

taxable income was above $58,261. Using the available 2016–17 rates for

Medicare Levy exemption from the ATO, a family with one child (and not entitled

to the seniors and pensioners tax offset) would be exempt up to a family

taxable income of up to $49,871 per annum.[102]

Table 1: 2017–18 and 2018–19 repayment income thresholds

and rates for HELP, SSL, and TSL and proposed new arrangements

| Repayment income thresholds 2017–18 |

Repayment rates 2017–18 |

Repayment income thresholds 2018–19 |

Repayment rates 2018–19 |

Repayment income thresholds 2018–19 as proposed in the

Bill |

Repayment rates 2018–19 as proposed in the Bill |

| |

|

|

|

Below $44,999 |

Nil |

| |

|

Below $51,956 |

Nil |

$45,000 – $51,956 |

1% |

| Below $55,874 |

Nil |

$51,956 –$57,729 |

2% |

$51,957 – $55,073 |

2% |

| $55,874 – $62,238 |

4% |

$57,730 – $64,306 |

4% |

$55,074 – $58,378 |

2.5% |

| $62,239 – $68,602 |

4.5% |

$64,307 – $70,881 |

4.5% |

$58,379 – $61,881 |

3% |

| $68,603 – $72,207 |

5% |

$70,882 – $74,607 |

5% |

$61,882 – $65,594 |

3.5% |

| $72,208 – $77,618 |

5.5% |

$74,608 – $80,197 |

5.5% |

$65,595 – $69,529 |

4% |

| $77,619 – $84,062 |

6% |

$80,198 – $86,855 |

6% |

$69,530 – $73,701 |

4.5% |

| $84,063 – $88,486 |

6.5% |

$86,856 – $91,425 |

6.5% |

$73,702 – $78,123 |

5% |

| $88,487 – $97,377 |

7% |

$91,426 – $100,613 |

7% |

$78,124 – $82,811 |

5.5% |

| $97,378 – $103,765 |

7.5% |

$100,614 –

$107,213 |

7.5% |

$82,812 – $87,779 |

6% |

| $103,766 and above |

8% |

$107,214 and above |

8% |

$87,780 – $93,046 |

6.5% |

| |

|

|

|

$93,047 – $98,629 |

7% |

| |

|

|

|

$98,630 – $104,547 |

7.5% |

| |

|

|

|

$104,548 – $110,820 |

8% |

| |

|

|

|

$110,821 – $117,469 |

8.5% |

| |

|

|

|

$117,470 – $124,517 |

9% |

| |

|

|

|

$124,518 – $131,988 |

9.5% |

| |

|

|

|

$131,989 and above |

10% |

Source: Recreated from ATO, ‘HELP,

SSL, ABSTUDY SSL, TSL and SFSS repayment thresholds and rates’, op. cit.;

Schedule 1 of the Budget

Savings (Omnibus) Act 2016; Parliament of Australia, Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (Student Loan Sustainability) Bill 2018

homepage, item 2 of Schedule 1.

Changes to SFSS

repayment thresholds

Part 1, items 3 to 5 of

Schedule 1 to the Bill propose to amend the Social Security Act 1991

to repeal current Section 1061ZZFD, which sets out the SFSS-specific repayment

thresholds and rates, and replace it with proposed section 1061ZZFD to apply

the repayment thresholds and rates under section 154–20 of the HESA from

2019–20, and establish transitional SFSS repayment rates and thresholds for

2018–19, as set out in Table 2 below. Proposed section 12ZLC of

the Student Assistance Act 1973, at item 6, has the same

effect.

Table 2: 2017–18 repayment income thresholds and

rates for SFSS and proposed transitional arrangements for 2018–19

| Repayment income thresholds 2017–18 |

Repayment rates 2017–18 |

Proposed transitional repayment income thresholds 2018–19 |

Proposed transitional rates 2018–19 |

| Below $55,874 |

Nil |

Below $57,730 |

Nil |

| $55,874 – $68,602 |

2% |

$57,731 – $70,881 |

2% |

| $68,603 – $97,377 |

3% |

$70,882 – $100,613 |

3% |

| $97,378 and above |

4% |

$100,614 or more |

4% |

Source: Recreated from ATO, ‘HELP,

SSL, ABSTUDY SSL, TSL and SFSS repayment thresholds and rates’, op. cit.;

Item 3, Parliament of Australia, Higher

Education Support Legislation Amendment (Student Loan Sustainability) Bill 2018

homepage, Australian Parliament website.

Changes to

indexation under HESA

Part 2 of Schedule 1 to the Bill proposes amendments

to change the indexation of repayment thresholds under HESA from AWE to CPI. The

application provisions in Part 3 propose to give effect to these changes

from the 2019–20 income year.

Currently, the repayment income thresholds are indexed by

the change in AWE for that income year under section 154–25 of the HESA.

Items 8 and 9 propose to repeal and replace the AWE indexation formula

in this section with the change in the index number for the

income year.

Index number is currently defined in clause 1

of the Dictionary at Schedule 1 to the HESA, as having, for the purposes

of Part 4–1 of HESA, the meaning given by section 140–15 and for the

purposes of Part 5–6, the meaning given by section 198–20. Item 14 proposes

to amend this definition by providing that for the purposes of Parts 4–1

and 4–2 of HESA, index number has the meaning given by proposed clause 2

of Schedule 1 to HESA, which is inserted by item 16 of Schedule 1

to the Bill.[103]

Proposed clause 2 provides that, for the purposes of Parts 4–1 and 4–2,

‘the index number for a quarter is the All Groups Consumer Price

Index number, being the weighted average of the 8 capital cities, published by

the Australian Statistician in respect of that quarter’. This mirrors the

definition of index number in section 198–20 of the HESA.

The effect of these changes is that the same indexation

formula currently applied to other HESA funding under Part 5–6

would apply to the loan repayment thresholds.[104]

As can be seen in the table at Appendix 1: Average Weekly Earnings (AWOTE), HELP repayment rates and thresholds: 1988–89 to 2016–17,

the minimum repayment threshold has generally remained around Average Weekly

Ordinary Time Earnings (AWOTE). Under section 154–25 of HESA, the repayment thresholds are subject to

indexation each year by the increase in average weekly earnings.[105]

As a consequence, the thresholds have tended to increase over time in real

terms until lower thresholds have been legislated. Andrew Norton, Higher Education Program Director for the

Grattan Institute, has recommended a shift to CPI indexation of the thresholds

to avoid this tension.[106]

However, it is important to note that during periods of slow wage growth below

CPI, such a change would see HELP repayment thresholds increase more quickly

than wages, creating more generous repayment arrangements over time—the

opposite to the intended effect.

Changes to

order of repayment of debts

As discussed above, debtors with borrowings under both SFSS

and other student loan schemes are currently required to make SFSS repayments concurrently

with the other student loan repayments once their income reaches the minimum

repayment threshold.

Referring to Table 1 and Table 2 above, this

would mean a debtor with SFSS and HELP borrowings and an income of $60,000 per

annum in 2017–18 would make HELP repayments of 4.0 per cent at the same time as

SFSS repayments of 2.0 per cent, bringing their repayment responsibilities up

to the 6.0 per cent level that would otherwise only apply to HELP debtors with

an income at least $17,619 higher—between $77,619 and $84,062.

Schedule 2 proposes amendments to the Social

Security Act 1991, Student Assistance Act 1973, and Trade Support

Loans Act 2014 to specify SFSS debts are to be paid after HELP, followed by

SSL, ABSTUDY SSL, and TSL. The application provisions contained in Part 2

of Schedule 2 specify that the amendments are to apply from the 2019–20

financial year. This commencement would be at the same time as the proposed

change to bring SFSS debts under the HELP repayment thresholds and rates in HESA.

Item 1 proposes amendments to the Social Security Act

1991 to repeal and replace subsection 1061ZVHA(1), which sets out the compulsory

SSL repayment liability. Under current subsection 1061ZVHA(1), compulsory

repayments must be made once a person’s income reaches the minimum repayment

threshold and the person has finished repaying any accumulated HELP debts. Proposed

subsection 1061ZVHA(1) adds accumulated SFSS debt, meaning SSL debt would

be repaid after HELP and SFSS, but before ABSTUDY SSL and TSL, if a person owes

under all programs.

Item 2 proposes amendments to the Student Assistance

Act 1973 to repeal and replace subjection 10F(1), which sets out the

compulsory ABSTUDY SSL repayment liability. Under current subjection 10F(1),

compulsory repayments must be made once a person’s income reaches the minimum

repayment threshold and the person has finished repaying any accumulated HELP and

SSL debt. Proposed subsection 10F(1) adds accumulated SFSS debt, meaning

ABSTUDY SSL debts would be repaid after HELP and SSL debts, but before TSL, if

a person owes under all programs.

Item 3 proposes amendments to the Trade Support Loans

Act 2014 to repeal and replace subsection 46(1), which sets out the

compulsory TSL repayment liability. Under current subsection 46(1), compulsory

repayments must be made once a person’s income reaches the minimum repayment

threshold and the person has finished repaying any accumulated HELP, SSL, or

ABSTUDY SSL debt. Proposed subsection 46(1) adds accumulated SFSS debt,

meaning TSL debts would be repaid last if a person owes under all student loan

programs.

Each of the proposed replacement subsections include debts

under section 154–16 of HESA as HELP debts. This means HELP repayments

charged as a levy under the Student Loans

(Overseas Debtors Repayment Levy) Act 2015 are treated as HELP

repayments for the purposes of repayment order.[107]

Introduction

of a combined HELP loan limit

As discussed above, under section 104–20 of HESA, a

lifetime borrowing limit, the FEE-HELP limit, currently applies to FEE‑HELP,

VET FEE-HELP and Vet Student Loans. In comparison, no borrowing limits

currently apply for HECS‑HELP, although a limit on the length of

Commonwealth supported study time available applied between 2005 and 2011.[108]

In 2018, the FEE-HELP lifetime borrowing limit is $127,992 for medicine,

dentistry and veterinary science students and $102,392 for all other students.[109]

Schedule 3 of the Bill proposes amendments to extend

the FEE-HELP limit, which would be renamed the ‘HELP limit’ to include all HELP

loans, and increase the loan limit for students undertaking medicine, dentistry

or veterinary science to $150,000. The application provisions outlined in Part

2 of Schedule 3 mean amendments would apply from 1 January 2019. No

changes are proposed to indexation of the loan limits, which are currently

indexed by CPI under Part 5-6 of HESA. The note to proposed section 128-20

(at item 54 of Schedule 3) confirms that loan limits are indexed.

Currently, a student who undertakes a Commonwealth

supported undergraduate degree and then continues their education by enrolling

in a postgraduate full fee-paying course only begins accruing debt towards the FEE-HELP

balance (and hence, borrowing limit) when they start using FEE-HELP, or, if

undertaking a VET qualification, VET Student Loans. The effect of the proposed

changes is that the HELP loan most often taken out by domestic undergraduate

students at public universities (HECS-HELP) will count towards the loan limit,

leaving a reduced HELP balance available for any further study.

According to Peter Dawkins, Vice-Chancellor of Victoria

University, income contingent loan caps ‘have a similar effect to a fee cap.’[110]

An effective cap limits fees in a deregulated market (such as currently exists

for domestic students studying postgraduate higher education courses, most

courses at non-university higher education providers, and many VET courses) as

the majority of students will be unable to pay above the set limit.

According to DET’s fact sheet on this measure ‘[t]he

limits are reasonable and sufficient, in most cases, to cover almost nine years

of study as a Commonwealth supported student.[111]

However, while Commonwealth supported fees are capped, some deregulated postgraduate

university course fees are already above the FEE-HELP loan limit, meaning this

assessment cannot be extended to the entire HELP portfolio. For example, Macquarie

University’s newly launched ‘Macquarie MD’ has an indicative annual fee of $64,000

for domestic students (who, under this program, are not eligible for a

subsidised ‘Commonwealth Supported Place’ or HECS-HELP), totalling approximately

$256,000 over the course of the four-year program.[112]

However, this is at the upper end of fees charged by Australian universities.

By comparison, the Australian National University Master of Laws annual

indicative fee for domestic students is $30,096, and consists of one year

full-time study.[113]

Item 54 of Schedule 3 inserts proposed Part 3–6 at the end of chapter 3 of HESA, to specify how the

HELP balance is to be worked out. Proposed section 128–15 sets out that a person’s HELP balance is comprised of the HECS-HELP,

FEE-HELP, VET FEE-HELP and VET student loans assistance provided to the person.

OS-HELP and SA-HELP are not included, although as discussed above spending

under these sub-schemes is already separately capped. The transitional

provisions set out at subitem 144(2) in Part 2 of Schedule 3 mean

that HECS-HELP assistance would not be applied to the HELP balance if the

census date for the unit is before 1 January 2019. Proposed subsection

125-15(2) specifies that for the purpose of working out the HELP balance,

it is immaterial whether the amounts provided have been repaid.

Proposed section 128–20

specifies that the HELP loan limit is $150,000 for students studying medicine,

dentistry and veterinary science courses, or $104,440 for all other students,

and that the HELP loan limit is indexed under Part 5–6.

Proposed section 93–20 at item 5 sets out the

limits of HECS-HELP, FEE-HELP, and VET FEE‑HELP assistance that may be

provided. Proposed subsection 93–20(2) specifies that if the sum of the

amounts to which the student would be entitled would exceed the student’s

available HELP balance on the census date, then the total amount of assistance

provided can only be up to the HELP balance.[114]

This means a student enrolling in a unit, or units with the same census date,

which cost more than the available HELP balance, would be liable to pay the

outstanding amount to the provider. Proposed subsection 93–20(3)

specifies that if a student is enrolled in units with more than one higher

education or VET provider, the student must notify each provider of the

proportion of the HECS–HELP, FEE-HELP, and VET FEE-HELP that is to be payable

for the units.

Item 6 will insert proposed Division 97, which

sets out the circumstances in which a person’s HELP balance is to be

re-credited in relation to HECS-HELP assistance. Currently under HESA,

providers must repay HELP loan amounts in certain circumstances, to avoid the

student incurring a debt improperly.[115]

These proposed amendments apply the conditions currently in place for

re-crediting the FEE-HELP balance in relation to FEE-HELP and VET FEE-HELP, in

light of the proposal to apply the borrowing limit currently in place for these

loans to HECS-HELP.

- Proposed

subsection 97–25(2) specifies that the provider must re-credit the

HECS-HELP assistance if special circumstances apply.

- Proposed

section 97–30 defines special circumstances for the purposes of the Division,

consistent with the definition currently at section 36–21 of HESA.

- Currently

under section 193–5 of HESA, a person is not entitled to HECS-HELP assistance

if they do not have a tax file number. Proposed section 97–27 specifies

that if a person’s enrolment is cancelled consistent with the provisions of

section 193–5, the HELP balance must be re-credited by the provider.

- Proposed

section 97–35 specifies that the student’s application for re-crediting

must be made within 12 months of the student’s withdrawal from the unit,

or if that does not apply, within 12 months of when the student undertook, or

was to undertake, the unit. Proposed section 97–40 specifies that the

provider can waive the requirement for the application to be made within the 12

month period if it was not possible for the application to the made during that

time.

- Proposed

section 97-42 specifies that a person’s eligible HELP balance must be

re-credited if the provider ceases to provide the course of which the unit is a

part.

- Proposed

subsections 97–25(3), 97–27(2) and 97–42(2) specify that the

Secretary of the relevant Department (currently DET) may act if the provider is

unable to re-credit the balance in the circumstances outlined in sections

97–25, 97–27 and 97–42.

The Bill does not contain any proposal to alter the OS-HELP

semester borrowing limit of $6,665 (if not studying in Asia) or $7,998 (if

studying in Asia), which can be expended twice during a course of study, or the

VET Student Loans course borrowing limits of $5,000, $10,000, $15,000 and

$75,000.

Items 122 to 143 of Schedule 3 deal with consequential

amendments to the VET

Student Loans Act 2016 to include VET Student Loans in the HELP loan

limit—changes largely consist of replacing ‘FEE-HELP balance’ with ‘HELP

balance’. The exception is item 123, which repeals the definition of

FEE-HELP balance as it is no longer needed, and item 124, which inserts

at section 6 the definition of HELP balance, specifying that it ‘has the same

meaning as in the Higher Education Support Act 2003’.

Concluding comments

This Bill presents a set of more narrowly focused higher

education reforms aimed to improve the sustainability of HELP. The lower

minimum repayment threshold and rate continues efforts to reduce the amount of

unpaid HELP debt, and the HELP loan limit extends arrangements currently in

place for VET Student Loans (previously VET FEE-HELP) and FEE-HELP to

Commonwealth supported students, returning domestic undergraduate students to

limited allocation similar to what was in place prior to the introduction of

the demand driven system. However, as Mark Warburton, Honorary Senior Fellow at

the LH Martin Institute, states:

There will always be a policy question

about the appropriate income level at which repayments should commence... Regardless

of where the repayment threshold is set, there will always be an amount of debt

that is ‘expected’ not to be repaid.[116]

In this way, these proposals, coupled with the other 2017–18

MYEFO higher education reform announcements, raise questions about the future

of the demand driven funding system and the role of HELP in increasing access

and participation in tertiary education.

Appendix 1: Average Weekly Earnings (AWOTE), HELP

repayment rates and thresholds: 1988–89 to 2016–17

1988–89 to 2003–04

| Income year |

AWOTE

($ pa)(a) |

Repayment rate and repayment threshold ($ pa)(b) |

| |

|

Nil |

1% |

2% |

3% |

3.5% |

4% |

4.5% |

5% |

5.5% |

6% |

| 1988–89(c) |

26

057 |

21

999 |

24

999 |

34

999 |

35

000+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1989–90 |

27

318 |

23

582 |

26

798 |

37

518 |

37

519+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1990–91 |

29

026 |

25

468 |

|

28

941 |

40

519 |

|

40

520+ |

|

|

|

|

| 1991–92 |

30

319 |

27

097 |

|

30

793 |

43

112 |

|

43

113+ |

|

|

|

|

| 1992–93 |

30

800 |

27

747 |

|

31

532 |

44

146 |

|

44

147+ |

|

|

|

|

| 1993–94 |

31

764 |

26

402 |

|

|

30

004 |

|

42

005 |

|

42

006+ |

|

|

| 1994–95 |

33

236 |

26

852 |

|

|

30

516 |

|

42

722 |

|

42

723+ |

|

|

| 1995–96 |

34

710 |

(d)19

999 |

|

27

674 |

31

449 |

|

44

029 |

|

44

030+ |

|

|

| 1996–97(e) |

35

942 |

(d)20

593 |

|

28

494 |

30

049 |

32

381 |

37

563 |

43

335 |

47

718 |

51

293 |

51

294 |

| 1997–98(e) |

37

344 |

20 700 |

|

|

21

830 |

23

524 |

27

288 |

32

934 |

34

665 |

37

262 |

37

263 |

| 1998–99(e) |

38

922 |

21

333 |

|

|

22

498 |

24

244 |

28

123 |

33

942 |

35

726 |

38

402 |

38

403 |

| 1999–00(f) |

40

037 |

21

983 |

|

|

23

183 |

24

982 |

28

980 |

34

976 |

36

814 |

39

572 |

39

573 |

| 2000–01(f) |

42

039 |

22

345 |

|

|

23

565 |

25

393 |

29 456 |

35

551 |

37

420 |

40

223 |

40

224 |

| 2001–02(f) |

44

270 |

23

241 |

|

|

24

510 |

26

412 |

30

638 |

36

977 |

38

921 |

41

837 |

41

838 |

| 2002–03(f) |

46

667 |

24

364 |

|

|

25

694 |

27

688 |

32

118 |

38

763 |

40

801 |

43

858 |

43

859 |

| 2003–04(f) |

48

571 |

25

347 |

|

|

26

731 |

28

805 |

33

414 |

40

328 |

42

447 |

45

628 |

45

629 |

2004–05 to 2016–17

| Income year |

AWOTE ($pa)(a) |

Repayment rate and repayment threshold

($ pa)(b) |

| |

|

Nil |

4% |

4.5% |

5% |

5.5% |

6% |

6.5% |

7% |

7.5% |

8% |

| 2004–05(f) |

50

929 |

35

000 |

38

987 |

42

972 |

45

232 |

48

621 |

52

657 |

55

429 |

60

971 |

64

999 |

65

000 |

| 2005–06(g) |

52

978 |

36

184 |

40

306 |

44

427 |

46

762 |

50

266 |

54

439 |

57

304 |

63

062 |

67

199 |

67

200 |

| 2006–07(g) |

55

143 |

38

148 |

42

494 |

46

838 |

49

300 |

52

994 |

57

394 |

60

414 |

66

485 |

70

846 |

70

847 |

| 2007–08(g) |

57

673 |

39

824 |

44

360 |

48

896 |

51

466 |

55

322 |

59

915 |

63

068 |

69

405 |

73

959 |

73

960 |

| 2008–09(g) |

60

991 |

41

598 |

46

333 |

51

070 |

53

754 |

57

782 |

62

579 |

65

873 |

72

492 |

77

247 |

77

248 |

| 2009–10(h) |

64

399 |

43

151 |

48

066 |

52

980 |

55

764 |

59

943 |

64

919 |

68

336 |

75

203 |

80

136 |

80

137 |

| 2010–11(h) |

67

077 |

44

911 |

50

028 |

55

143 |

58

041 |

62

390 |

67

750 |

71

126 |

78

273 |

83 407 |

83

408 |

| 2011–12(h) |

69

662 |

47

195 |

52

572 |

57

947 |

60

993 |

65

563 |

71

006 |

74

743 |

82

253 |

87

649 |

87

650 |

| 2012–13(h) |

73

239 |

49

095 |

54

688 |

60

279 |

63

448 |

68

202 |

73

864 |

77

751 |

85

564 |

91

177 |

91

178 |

| 2013–14(h) |

75

169 |

51

308 |

57

173 |

62

997 |

66

308 |

71

277 |

77

194 |

81

256 |

89

421 |

95

287 |

95

288 |

| 2014–15(h) |

76

963 |

53

345 |

59

421 |

65

497 |

68

939 |

74

105 |

80

257 |

84

481 |

92

970 |

99

069 |

99

070 |

| 2015–16(h) |

78

429 |

54 125 |

60

292 |

66

456 |

69

949 |

75

190 |

81

432 |

85 718 |

94

331 |

100 519 |

100 520 |

| 2016–17(h) |

|

54 868 |

61

119 |

67

368 |

70

909 |

76

222 |

82

550 |

86

894 |

95

626 |

101

899 |

101

900 |

| 2017–18(h) |

|

55

873 |

62

238 |

68

602 |

72

207 |

77

618 |

84

062 |

88

486 |

97

377 |

103

765 |

103

766 |

(a)

Average weekly ordinary time

earnings for adults working full time (calculated as average weekly ordinary

time earnings for the two quarterly survey estimates multiplied by 52 weeks)

(b)

Highest income level at which rate

is payable, except for top repayment rate, which commences at income level

specified

(c)

As HECS was only introduced on 1

January 1989, repayment rates for 1988–89 were at half the level of later years

(that is, 0.5%, 1.0% and 1.5%)

(d)

Repayment at 2% rate was voluntary

(e)

Taxable income plus net rental

losses

(f)

As per (e) plus total reportable

fringe benefits amounts

(g)

As per (f) plus exempt foreign

employment income

(h)

As per (g) plus any total

investment loss (which includes net rental losses), and reportable super

contributions.

Sources: Australian Taxation Office (ATO), ‘HELP, SSL, ABSTUDY SSL, TSL and SFSS repayment

thresholds and rates’, op. cit., Earlier years sourced from ATO

websites now archived at National Library of Australia, Australian Government web archive; ABS, Average weekly earnings, Australia, ‘Table

3’, cat. no. 6302.0, ABS, Canberra, 23 February 2017.

Members, Senators and Parliamentary staff can obtain

further information from the Parliamentary Library on (02) 6277 2500.

[1]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Higher Education Support Legislation Amendment (Student Loan

Sustainability) Bill 2018, p. 1.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. A

more detailed outline of the HELP loans is available from C Ey, Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide,

Research paper series, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra 2017.

[4]. Australian

Tax Office (ATO), ‘HELP,

SSL, ABSTUDY SSL, TSL and SFSS repayment thresholds and rates’, ATO

website, last modified 9 May 2017.

[5]. See

Schedule 1 of the Budget

Savings (Omnibus) Act 2016. This Act also discontinued the HECS-HELP

benefit, which reduced HELP repayments for graduates of particular courses who

chose to take up related occupations or work in specific locations, from 1 July

2017 (Schedule 3). Both of these measures were in the 2014–15 Budget. Australia

Government, Portfolio

budget statements 2014–15: budget related paper no. 1.5: Education Portfolio,

p. 23.

[6]. Ey,

Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide, op.

cit., p. 2.

[7]. Department

of Education and Training (DET), Annual

report 2016–17: opportunity through learning, DET, [Canberra], 2017, p.

45.

[8]. DET,

‘FEE-HELP’,

StudyAssist website.

[9]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 53.

[10]. DET,

‘FEE-HELP’,

op.cit. The fee does not contribute to debts under the cap, or apply to

postgraduate study, including higher degrees by research, enabling courses,

courses undertaken through Open Universities Australia, or bridging study for

overseas-trained professionals.

[11]. DET,

‘2016 liability status

categories’, Table 5.1: actual student load (EFTSL) for all students by

liability status and broad level of course, full year 2016, DET website, 11

September 2017. 28,050 EFTSL includes all undergraduate student load under

‘deferred all or part of award or enabling course tuition fee’, except that for

enabling courses. This may be a slight over-estimation as it may include Open

Universities Australia or bridging study students.

[12]. Ey,

Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide,

op. cit., p. 3.

[13]. The

fee is capped and indexed each year. DET, ‘Student

services and amenities fee’, DET website.

[14]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 53.

[15]. Ey,

Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide,

op. cit., pp. 2–3.

[16]. DET,

‘OS-HELP

loans and overseas study’, StudyAssist website.

[17]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 53.

[18]. Australian

Government, ‘Part

2: expense measures’, Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2009–10, p.

152. See ‘An Innovation and Higher Education System for the 21st Century—remove

the loan fee on OS‑HELP

loans’.

[19]. Ey,

Higher

Education Loan Program (HELP) and other student loans: a quick guide,

op. cit., p. 3.

[20]. DET,

‘VET student loans’,

DET website, last modified 18 December 2017. Approved courses are only from

higher-level VET qualifications, including diploma, advanced diploma, graduate certificate

or graduate diploma, according to DET, ‘VET

student loans’, StudyAssist website.

[21]. DET,

‘VET

student loans’, StudyAssist website.

[22]. DET,

VET

student loans: information for students applying for VET student loans,

June 2017, p. 19. Under the National

Partnership Agreement on Skills Reform, the states and territories agree to

pay half of the debt not expected to be repaid and half of the concessional

loan cost for VET-FEE HELP loans (now VET student loans) for subsidised

students. This is ‘paid annually in arrears based on actuarial assessments

undertaken by the Commonwealth’ (Schedule 4). These arrangements were

established as an alternative to applying a loan fee to state and territory

Government subsidised VET courses. The lack of loan fee charge for these

purposes is established under part 3 of the VET Student Loans

Rules 2016, for the purposes of paragraph 137-19(2)(b)

of HESA.

[23]. This

is discussed in further detail in J Griffiths, VET

Student Loans Bill 2016 [and] VET Student Loans (Charges) Bill 2016 [and] VET

Student Loans (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2016,

Bills digest, 41, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2016. According to

DET, a ‘Review

of the VET student loans approved course list and loan caps methodology’

was undertaken in 2017, finding ‘[t]here was no compelling evidence to warrant

significant change to the loan cap amounts at this early stage of the program.’

The most recent available data on VET Student Loan uptake is available from DET,

VET

student loans: six-monthly report: 1 July 2017 to 31 December 2017,

DET website.

[24]. Under

the VET Student

Loans (Courses and Loan Caps) Determination 2016, these amounts are indexed

each year from 2018.

[25]. The

size of the HELP loan portfolio can be estimated in two ways: the nominal value

and the fair value. The nominal value is the total face value of outstanding

HELP loans, which increases as new loans are issued and indexation is applied,

and decreases as loans are repaid. The fair value accounts for ‘losses’— that

is, debt not expected to be repaid and the difference between the indexation

applied to the loan and market interest rates. Therefore, while the fair value

is lower than the total amount of outstanding debt, it is considered to more

accurately reflect its future impact on Government cash flows. See

Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Higher

Education Loan Programme: Impact on the Budget, Report no. 2, 2016, p.

5 for more information.

[26]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 45.

[27]. Ibid.

[28]. Relevant to HELP estimates, the Higher Education Support Legislation Amendment (A More

Sustainable, Responsive and Transparent Higher Education System) Bill 2017 included: from 2018, increased student contributions

of 7.5 per cent, to be phased in through an annual 1.8 per cent

increase over four years from 2018; an efficiency dividend of 2.5 per cent

applied to the Commonwealth Grant Scheme (CGS) in 2018 and 2019; a new set

of HELP repayment thresholds from 1 July 2018, including a minimum repayment

threshold on annual income in 2018–19 of $42,000 with a one per cent repayment

rate, and a maximum income threshold of $119,882 with a repayment rate of ten

per cent; from 1 July 2019 onwards, all HELP thresholds indexed by the Consumer

Price Index (CPI), instead of Average Weekly Earnings (AWE).

[29]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 45.

[30]. DSS,

‘5.1.7.45

Student start-up scholarship – current rate’, Guide to Social Security

Law, 20 March 2018.

[31]. DSS,

‘1.2.7.165

Student start-up loan (SSL) – description’, Guide to Social Security Law,

20 March 2018.

[32]. Department

of Human Services (DHS), ‘Student

start-up loan’, DHS website, last updated 27 October 2017.

[33]. Ibid.

[34]. DSS,

‘6.9 SSL

repayment arrangements’, Guide to Social Security Law, 20 March

2018.

[35]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 65.

[36]. Unless

otherwise indicated, information in this paragraph is from DET, ‘Trade

support loans’, Australian Apprenticeships website.

[37]. DET,

‘Trade

support loans priority list’, Australian Apprenticeships website.

[38]. Trade Support Loans

Act 2014 subsection 46(1).

[39]. DET,

Annual

Report 2016–17, op. cit., p. 65.

[40]. D

Daniels, Family