Bills Digest no. 88, 2017–18

PDF version [462KB]

Liz Wakerly, Economics Section

Paula Pyburne, Law and Bills Digest Section

19 March 2018

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Personal insolvency

Operation of the Bankruptcy Act

Declaration of intention

Bankruptcy

Personal insolvency agreement

Debt agreements

Concerns with the debt agreement

framework

Committee consideration

Senate Legal and Constitutional

Affairs Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Treasury consultation

ASIC report

Committee inquiry

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 1–Debt agreement proposals

Part 1–Persons who may be authorised

to deal with debtor’s property

Commencement and application

Part 2—Reimbursement of expenses

Commencement and application

Part 3—Value of debtor’s property

Commencement and application

Part 4—Payment to income ratio

Commencement and application

Part 5—Undue hardship to debtor

Commencement and application

Part 6—Other matters

Schedule 2—Debt agreements

Part 1—Length of debt agreements

Commencement and application

Part 2—Proposals to vary debt

agreements

Key issue—Sustainability

Key issue—Conflicts of interest

Key issue—Valuable consideration

Commencement and application

Part 3—Proposals to terminate debt

agreements

Commencement and application

Part 4—Court orders to terminate debt

agreements

Part 5—Voiding debt agreements

Commencement and application

Part 6—Debt agreement administrators

to refer evidence of offences

Commencement and application

Part 7—Reporting requirements for

debtors in arrears

Commencement and application

Part 8—Alignment of offences

Separate bank accounts

Sufficient records

Commencement and application

Part 9—Time for submitting annual

returns

Commencement and application

Schedule 3—Registered debt agreement

administrators

Part 1—Applications for registration

Insurance

Interview

Evidence

Registration renewal

Commencement and application

Part 2—Conditions of registration

Commencement and application.

Part 3—Ongoing obligation to maintain

insurance

Commencement and application

Part 4—Cancellation of registration

Commencement and application

Part 5—Trust accounts

Commencement and application

Part 6—Functions of Inspector-General

Commencement and application

Other provisions

Schedule 4—Registered trustees

Commencement and application

Schedule 5—Unclaimed money

Application and saving provisions

Appendix 1: Personal insolvencies,

Australia

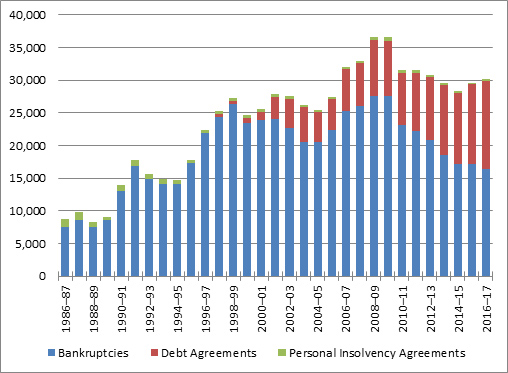

Figure 1: Personal insolvencies,

Australia 1986–87 to 2016–17

Appendix 2: Formal options for

insolvency

Date introduced: 19 February 2018

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Attorney-General

Commencement: Various dates as set out in the body of this Bills Digest.

Links: The links to the Bill, its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the Bill’s home page, or through the Australian Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as at March 2018.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

The Bill amends the Bankruptcy Act 1966

to effect a comprehensive reform of Australia’s debt agreement system in the

following manner:

- Schedule

1 – Debt agreement proposals modifies the requirements for and treatment

of, debt agreement proposals

- Schedule

2 – Debt agreements sets standards for the operation of debt agreements

- Schedule

3 – Registered debt agreement administrators modifies the standards that

registered administrators must satisfy

- Schedule

4 – Registered trustees contains technical amendments and

- Schedule

5 – Unclaimed money modifies the requirements for registered personal

insolvency practitioners to pay unclaimed moneys to the Commonwealth.

Background

Debt agreements were introduced in 1996 as a form of

insolvency administration outside bankruptcy for persons with low levels of

debt, few assets and low incomes. In 2016–17, debt agreements accounted for

more than 45 per cent of all personal insolvencies. Commentators have expressed

concerns that debt agreements may be causing harm, particularly to those vulnerable

debtors on low incomes for whom they were originally intended. Key concerns

relate to the use of inappropriate sales techniques by debt agreement

administrators, inadequate understanding by firms of the relevant law and risks

of particular strategies, opaque and often high administrator fees and costs, and

inflexible repayment plans.

Key issues and provisions

The Bill:

- sets

stricter practice standards for debt agreement administrators (including

compulsory registration), tougher penalties for wrongdoing and grants the

Inspector-General additional investigative powers to address misconduct

- requires

debt agreement administrators to: hold and maintain professional indemnity and

fidelity insurance as a requirement of registration; and to be fit and proper

persons

- clarifies

the types of expenses that debt agreement administrators can recover

- links

debt agreement repayments to a specified percentage of income, with the

percentage determined by legislative instrument

- limits

the length of a debt agreement proposal to three years (in line with bankruptcy

provisions)

- doubles

the current asset eligibility threshold to be eligible to propose a debt

agreement

- provides

the Official Receiver with the ability to reject proposed debt agreements that

would cause undue financial hardship to the debtor

- reduces

the potential for conflicts of interest in the proposal, variation and

termination of debt agreements, and aligning offences with those applicable to

bankruptcy trustees and

- extends

the possibility of voiding a debt agreement to the situation where a debt

agreement administrator has breached conditions or duties.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Bankruptcy Amendment (Debt Agreement

Reform) Bill 2018 (the Bill) is to amend the Bankruptcy Act 1966

(the Bankruptcy Act) to effect a comprehensive reform of Australia’s

debt agreement system. Significant measures in the Bill make provision for:

- the

types of practitioners authorised to be debt agreement administrators

- registration,

deregistration and obligations of debt agreement administrators

- formation,

administration, variation and termination of debt agreements

- protections

against debt agreements that cause financial hardship or have other defects and

- powers

of the Inspector-General in Bankruptcy (the Inspector-General) with respect to

debt agreements and debt agreement administrators.

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill comprises five Schedules:

- Schedule

1 – Debt agreement proposals modifies the requirements for and treatment

of, debt agreement proposals. Amendments include:

- limiting

the types of practitioners authorised to be debt management agreement

administrators

- the

types of information the debtor must record in a debt agreement proposal

- the

certifications the proposed administrator must make

- the

standards for how the Official Receiver must handle proposals

- Schedule

2 – Debt agreements sets standards for the operation of debt agreements

covering:

- the

length of debt agreements

- mechanisms

for varying, terminating and voiding debt agreements

- an

administrator’s duties in the administration of debt agreements

- Schedule

3 – Registered debt agreement administrators modifies the standards that

registered debt agreement administrators must satisfy, including:

-

prerequisites

and conditions for registration

- ongoing

obligations

- grounds

for deregistration

- trust

accounts

- functions

of the Inspector-General

- Schedule

4 – Registered trustees contains technical amendments

- Schedule

5 – Unclaimed money modifies the requirements for registered personal

insolvency practitioners to pay unclaimed moneys to the Commonwealth, and the

process to apply for unclaimed moneys.

Background

Personal

insolvency

The Australian

Financial Security Authority (AFSA), which is an executive agency in the

Attorney-General’s portfolio, manages the application of bankruptcy and

personal property securities law through the delivery of personal insolvency

and trustee, regulation and enforcement and personal property securities

services.[1]

Under the Bankruptcy Act, there are four options

for individuals facing unmanageable debt:

- a

declaration of intention (DOI) to present a debtor’s petition which provides

temporary relief while being pursued by creditors (Division 2A in Part IV of

the Bankruptcy Act)

- bankruptcy

which includes a debtor’s petition (voluntary bankruptcy) (Division 3 in Part

IV of the Bankruptcy Act) and a creditor’s petition (Division 2 in Part

IV of the Bankruptcy Act)

- personal

insolvency agreements (Part X of the Bankruptcy Act) and

- debt

agreements (Part IX of the Bankruptcy Act).[2]

Appendix 1 to this Bills Digest contains a chart

illustrating the number of new administrations of personal bankruptcies, debt

agreements and personal insolvency agreements in Australia for the period 1986–87

to 2016–17. Debt agreements have become increasingly popular: in 2016–17, debt

agreements accounted for more than 45 per cent of all personal insolvencies, up

from less than two per cent in 1997–98.

The AFSA website provides comparison

tables for the three agreement options, looking at eligibility, income

payments, restrictions on employment, the treatment of assets and the nature of

debts, personal restrictions, and fees and charges. These tables are shown in Appendix

2 to this Bills Digest.[3]

Operation

of the Bankruptcy Act

Declaration

of intention

A DOI provides a 21-day protection period where unsecured

creditors cannot take further action to recover debts.[4]

Details of the DOI do not appear on the National Personal Insolvency Index

(NPII). A DOI does not automatically make a debtor bankrupt, but creditors can

use the fact that a DOI has been lodged to apply to the court to make a debtor

bankrupt.[5]

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy brings a definite end to debt problems, with

creditors dealing exclusively with the bankruptcy trustee.[6]

A bankrupt must provide details of debts, income and assets to the trustee who

can sell certain assets to help pay debts. If a bankrupt’s income exceeds a set

amount, the bankrupt may need to make compulsory payments to the trustee. A

bankruptcy may impose restrictions on employment and overseas travel, may

affect a bankrupt’s ability to obtain future credit and appears permanently on

the NPII.[7]

Currently, a bankrupt will automatically be discharged

from bankruptcy if three years and one day have passed since a statement of

affairs was filed.[8]

Personal

insolvency agreement

A personal insolvency agreement (PIA), also known as a

Part X, is a legally binding agreement between a debtor and his or her

creditors. The PIA involves the appointment of a trustee to take control of

property and make an offer to creditors. The offer may be to pay all or part of

debts by instalments or a lump sum. There are no debt, asset or income limits

to be eligible for a PIA and the length of the PIA will depend upon

negotiations with the trustee and creditors. Fees apply to propose, lodge and

manage a PIA.[9]

A PIA is an act of bankruptcy with debtor details

appearing on the NPII permanently. Debtor details will appear on a credit file

for up to five years (or longer) and consent of the controlling trustee is

required before dealing with property. Under a PIA, a debtor cannot manage a

corporation until the terms of the agreement have been finalised.

Debt

agreements

A debt agreement is a legally ‘binding agreement between

an insolvent debtor and his or her creditors under which the creditors agree to

accept a sum of money the debtor can afford to pay’.[10]

Debt agreements were introduced into Australian law in 1996, and were intended

to offer a more flexible, less onerous and socially stigmatising alternative to

bankruptcy.[11]

A debt agreement begins with a proposal, put by the debtor

to his or her creditors. This proposal must satisfy specific conditions set out

in Part IX of the Bankruptcy Act, and must be lodged with AFSA

using prescribed forms.[12]

To be eligible to propose a debt agreement, unsecured debts and assets must be

less than $111,675.20, and annual after-tax income must be less than

$83,756.40.[13]

A debt agreement requires a debtor to negotiate a

percentage of the combined debt that can be repaid over a period of time

(usually between three and five years); repayments are made to a debt agreement

administrator; and once payments are complete and the agreement ends, creditors

cannot recover any outstanding monies owed.[14]

Debt agreements are subject to the oversight of the

Official Receiver, AFSA. If the Official Receiver is satisfied that the debt

agreement proposal is in accordance with regulatory requirements and

eligibility criteria have been met, the proposal is distributed to creditors.

The proposal becomes a binding agreement if enough creditors vote to accept it.[15]

Fees are charged for lodging a debt agreement proposal with

AFSA and for proposing and managing a debt agreement.[16]

Debt agreements cover most unsecured debts, or a debt not tied to specific

property.[17]

Proposing a debt agreement is an act of bankruptcy. The

key difference between bankruptcy and a debt agreement is that a debtor with

significant assets will lose those assets under bankruptcy but can retain them

with a debt agreement.[18]

The amount of time a debt agreement appears on the NPII

varies with the type of agreement and how it ends (ranging from one year to

five years from the date the debt agreement was made or the date the

obligations are complete, whichever is longer).[19]

If a debtor is unable to make payments as agreed, he or

she may seek to vary the terms of the debt agreement by lodging a proposal with

the Official Receiver.[20]

Any variation is subject to the consent of a majority of creditors. Debt

agreements may be terminated if the debtor defaults on payments for six months

or more, or becomes bankrupt; by an order of the Court; or where a proposal to

terminate the agreement is accepted by a majority in value of creditors.[21]

Concerns

with the debt agreement framework

Commentators have expressed concern that debt agreements

may be causing harm, particularly to vulnerable debtors on low incomes.[22]

There is no uniform regulatory framework applying to the

activities of debt management firms in Australia. Firms are not required to

hold a credit licence or an Australian Financial Services Licence to provide

debt management services.[23]

Not all debt agreement administrators are registered. A

debt agreement administrator is only required to be formally registered if: the

debt agreement administrator intends to lodge new debt agreement proposals

after 1 July 2007; and if the debt agreement administrator is already

administering more than five active agreements.[24]

Inspector-General

Practice Statement 2 outlines the requirements on a debt agreement

administrator to become registered.[25]

Currently, this includes passing a basic eligibility test and an examination of

their capability to perform the duties. As at 30 June 2017, there were 78

registered debt agreement administrators.[26]

Critics argue that some debt agreement administrators fail

to inform debtors of the full implications of signing a debt agreement,

maintaining that many debtors would be better off attempting to negotiate

repayment arrangements or debt waivers through financial hardship schemes or

external dispute resolution.[27]

For many low-income debtors, debt agreements prolong financial hardship;

bankruptcy would offer immediate relief.

The Inspector-General in Bankruptcy, AFSA’s Chief

Executive, has powers to regulate bankruptcy trustees and debt agreement

administrators (registered and unregistered), review decisions of trustees and

investigate allegations of offences under the Bankruptcy Act.[28]

Eight registered debt agreement administrators were inspected in 2016–17, along

with 49 of their administrations. Sixteen errors were identified, of which

seven concerned ‘failure to comply with certification duties’.[29]

It has been argued that some administrators encourage

low-income debtors to enter into agreements that are unsustainable.[30]

In 2015, a group of researchers at the Melbourne Law School undertook a national

online survey of financial counsellors, consumer solicitors and other

advocates who specialise in helping financially distressed individuals.[31]

The survey found that many of these advocates were ‘highly sceptical about the

value of debt agreements’. In particular, several advocates reported that debt

agreements often require clients to make regular repayments that they cannot

afford resulting in ‘continual hardship’. Some debt agreement administrators

were found to adopt inappropriate sales techniques, including failing to

disclose all relevant information to potential clients.[32]

When the debt agreement framework was established, it was

not expected that private, profit-making institutions would assume a prominent

role. In particular, it was ‘not proposed that there would be any fees or

administrative charges associated with debt agreements’.[33]

Critics of the current system maintain that high administrator fees result in

lower returns for creditors. In its online survey, Melbourne Law School

researchers reported criticism of the high administrative costs built into debt

agreements (in some cases greater than the original debt) and the inflexibility

of the repayment plans.[34]

Committee

consideration

Senate

Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee

The Bill has been referred to the Senate Legal and

Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee (the Committee) for inquiry and

report by 19 March 2018. Details of the inquiry are available here.

The Bill was referred to provide relevant stakeholders with the opportunity to

provide feedback and to allow for consideration of expert views on potential

impacts.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, the Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had not commented on the Bill.

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Speaking in relation to the Bill, the Shadow

Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, stated that the Australian Labor Party would support

the Bill, ‘subject to any necessary amendments arising as recommendations from

the ongoing Senate inquiry’—in particular with reference to the three-year time

limit for debt agreement repayments.[35]

Mr Dreyfus expressed concern that the percentage cap on a debtor’s after-tax

income that can be repaid in the repayment schedule is subject to Ministerial

discretion, preferring this percentage be given a statutory footing.[36]

Position of

major interest groups

Treasury

consultation

The improvement of the bankruptcy and insolvency regimes

is part of the Government’s National

Innovation and Science Agenda which was announced by the Prime Minister, Mr

Turnbull on 7 December 2015.[37]

In conjunction with that announcement, Treasury circulated a consultation paper

entitled National

Innovation and Science Agenda – Improving bankruptcy and insolvency laws, and

sought public comment about ways in which to improve the relevant laws. In

their submissions to the Treasury, Financial Counselling Australia (FCA), the

Financial Rights Legal Centre and the Consumer Action Law Centre all advocated

for a full review of debt agreements.[38]

The Financial Rights Legal Centre argued that consumers are frequently misled

about the nature and consequences of debt agreements: ‘advantages are

consistently oversold and the disadvantages downplayed’.[39]

Common misperceptions about debt agreements include:

- it

is a debt consolidation rather than an insolvency option

- there

will be no effect on the ability to obtain credit

- there

will be no effect on the debtor’s trade licence or ability to continue in their

profession

- there

are no other options available to deal with financial difficulty and

- payments

made up from for the preparation of the debt agreement will ultimately be set

off against the debts (the payment is for the preparation of the debt agreement

and is not set off against anything. It is rarely refunded if the debt

agreement is rejected and many clients put themselves into default on their

credit obligations in order to make these payments).[40]

The Financial Rights Legal Centre recommended:

- debt

agreements be limited to potential debtors with a material divisible asset to

protect

- advertising

is not misleading and makes it clear that debt agreements are an act of

insolvency under the Bankruptcy Act, and

- AFSA

publish more comprehensive statistics on debt agreements.[41]

The Consumer Action Law Centre also proposed a minimum

standard of entry for debt agreements, including an income above the income

threshold in the Bankruptcy Act, and an asset that could be

seized under bankruptcy.[42]

ASIC report

In a 2016 report, the Australian Securities and

Investments Commission (ASIC) presented the findings of research into debt

management firms in Australia.[43]

Using both qualitative and quantitative techniques, the report presents some

key findings:

- a

growing number of debt management firms offer a wide range of services to

consumers including representing consumers at external dispute resolution (EDR)

- fees

and costs were opaque, often high and heavily ‘front loaded’

- some

sales techniques created a high pressure sales environment

- little

information was given about risks

- some

firms had a poor understanding of the relevant law and consequences of

particular strategies

- firms

rarely referred consumers in financial hardship to free, alternative sources of

help or advised consumers that they could resolve the problem themselves at no

cost

- most

disputes brought to EDR schemes by debt management firms relate to arguments

about the removal of default listings on consumer credit reports

- while

an increasing number of consumers are being represented at EDR by debt

management firms, that is not leading to more credit reporting related disputes

being found in favour of consumers.

Committee inquiry

In its submission to the Committee Inquiry, the Personal

Insolvency Professionals Association (PIPA) argued that ‘a near perfect regime

of Debt Agreement is now being amended to create unforeseen implications for

debtors and the economy at large’.[44]

PIPA represents Registered Debt Agreement Administrators (RDAAs) whose members

are required to abide by a Code of Conduct.

PIPA argues for exempting the value of the family home

from the asset eligibility threshold (Schedule 1, Part 3, item 17 of the Bill),

on the grounds that, under the National Consumer

Credit Protection Act 2009, if a consumer could only comply with their

financial obligations by selling their principal place of residence, or the

consumer could only comply with those obligations with substantial hardship

(contrary to the intent in Schedule 1, Part 5, item 23 of the Bill).[45]

PIPA also had some concerns about the introduction of a percentage-based

payment to income ratio where the Minister has the power to determinate the

percentage by legislation instrument (Schedule 1, Part 4, item 21 of the

Bill);[46]

and on the three-year limit to debt agreements (Schedule 2, Part 1, item 1

of the Bill).[47]

These concerns largely relate to the imposition of a ‘one rule fits all’

approach which is too rigid. PIPA proposes automatic approval for debt

agreements which have an assured return to creditors; and, if zero votes are

received at the initial proposal, the debt agreement proposal be accepted as

proposed.

On the other hand, the Australian Restructuring Insolvency

and Turnaround Association (ARITA), considers that ‘the measures contained in

the Bill will improve trust and confidence in the debt agreement system’.[48]

ARITA raised some concerns with:

- the

proposal to double the debt agreement access threshold which applies to a

debtor’s property, while leaving threshold amounts for debts and income

unchanged[49]

- capping

the length of debt agreements to three years, to align with the period of

income contributions in bankruptcy[50]

- the

potential outcomes with the concurrent introduction of the Bill and the Bankruptcy

Amendment (Enterprise Incentives) Bill 2017 (which is proposing a reduction

in the default bankruptcy period to one year).[51]

The Australian Banker’s Association (ABA) does not support

the proposed reduction in the maximum term of a debt agreement, arguing that,

with more stringent requirements, longer term plans could be more successful.[52]

The additional requirements include a review of AFSA’s framework for debt

agreement proposal assessments, the establishment of an independent complaint

and dispute resolution mechanism for debtors, a re-examination of the impacts

of doubling the assets threshold for debtors combined with an ‘unseen

regulatory calibration methodology’, and a request to deal with ‘step ups’

whereby debtor payments increase in the final two years of an agreement.[53]

The Institute of Public Accountants (IPA) noted that the

overall benefits of the proposed amendments to the debt agreement legislation

may be ‘substantially affected’ if the proposed one-year bankruptcy term is

introduced.[54]

In particular:

- given

a choice between a debt agreement and bankruptcy, a debtor is more likely to

choose the administration with the shortest timeframe to completion[55]

and

- if

fewer debt agreements are entered into, the overall return to creditors may

fall (as the number of bankruptcies increase).[56]

In his submission, Professor Christopher Symes, a

bankruptcy law academic, expressed support for the Bill, and in particular, for

the three-year maximum term for debt agreements.[57]

He suggested publication of criteria to establish ‘fit and proper person’ in

the assessment of debt agreement administrators.[58]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory

Memorandum states that the Bill will have no direct financial impact.[59]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[60]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, the

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had not commented on the Bill.

Key issues

and provisions

This section examines the key provisions in Schedules 1 to

3, which contain the main amendments relating to debt agreements. Schedule 4

(which contains technical amendments) and Schedule 5 (which is concerned with

unclaimed money procedures) are addressed in the following section.

Schedule

1–Debt agreement proposals

Part

1–Persons who may be authorised to deal with debtor’s property

The amendments in Schedule 1 to the Bill modify the

requirements for, and treatment of, debt agreement proposals.

Currently subsection 185C(1) of the Bankruptcy Act

provides that a debtor who is insolvent may give the Official Receiver a

written proposal for a debt agreement. Subsection 185C(2) specifies the matters

which must be included in the debt agreement proposal. Items 1

and 2 amend subsection 185C(2) of the Bankruptcy Act so that only

a registered debt agreement administrator, registered trustee or the Official

Trustee can be authorised to administer a debt agreement. Currently, a

registered trustee, the Official Trustee or ‘other person’ can administer a

debt agreement, where ‘other person’ must pass a basic eligibility test (subsection

185E(2A) and cannot administer more than five debt agreements at a time

(subsection 185E(2B). Item 3 of Part 1 in Schedule 1 to the Bill makes

consequential amendments to section 185E of the Bankruptcy Act to repeal

these requirements.

Commencement

and application

Items 1–3 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Bill

commence six months after Royal Assent.

The amendments will apply to debt agreement proposals

given to the Official Receiver on or after commencement.[61]

Item 5 is a transitional provision which allows the

Official Trustee to replace an unregistered administrator, 12 months after

Royal Assent. This gives an unregistered administrator an opportunity to register

as a debt agreement administrator or trustee if they wish to keep administering

the debt agreement(s) they are currently administering. If the Official Trustee

replaces an unregistered administrator and the replacement results in an

acquisition of property from the administrator otherwise than on just terms,

the Commonwealth is liable to pay compensation to the administrator.

Items 6–11 of Part 1 in Schedule 1 to the Bill are

minor consequential amendments which commence 12 months after Royal Assent.

Part 2—Reimbursement

of expenses

According to the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill:

Currently it is not clear what debt agreement administrators

can claim as expenses, how they may recover the expenses, and who bears the

cost of the expenses. Most debt agreement administrators recover expenses

directly from the funds held in trust for the administration of the debt

agreement. Debt agreement administrators take expenses in priority to creditors

which are party to the debt agreement, which reduces the creditors’ expected

return.[62]

Subsection 185C(3) of the Bankruptcy Act allows a

debt agreement proposal to provide for the remuneration of a debt

administrator—other than the Official Trustee. Subsection 185C(3A) provides

that the debt proposal agreement must specify the total remuneration of the

debt administrator, worked out as a percentage of the total amount payable by

the debtor.

Item 13 of Part 2 in Schedule 1 to the Bill provides

that a debt agreement proposal must detail the types of expenses the debt

agreement administrator can recover.[63]

Items 14 and 15 provide that the debt agreement administrator has

a duty to not reimburse themselves for expenses that were not specified in the

new subsection.[64]

Commencement

and application

The amendments in item 13 will apply to debt

agreement proposals given to the Official Receiver six months after Royal

Assent (item 16). Items 14 and 15 will apply to debt agreements

that come into force on or after commencement of item 16.

Part 3—Value

of debtor’s property

Currently, a debtor is prevented from giving the Official

Receiver a debt agreement proposal if, at the proposal time, the value of their

property that would be divisible among creditors if the debtor were bankrupt

(the assets threshold) is more than the threshold amount.[65]

As of 31 January 2018, this amount was $111,675.20.[66]

Item 17 amends subsection 185C(4) so that a debtor

cannot give the Official Receiver a debt agreement proposal if, amongst other

things, the value of the debtor’s divisible property is double the threshold

amount. According to the Explanatory

Memorandum, ‘recent rises in Australian property prices means that the

current threshold amount prevents a significant proportion of Australians from

accessing the debt agreement system’.[67]

Commencement

and application

The higher assets eligibility threshold will apply to debt

agreement proposals given to the Official Receiver six months after Royal

Assent (item 18).

Part 4—Payment

to income ratio

Currently there is no specific restriction on the size or

frequency of a debtor’s proposed payments under a debt agreement. Rather the Bankruptcy

Act requires that a debt agreement proposal given to the Official Receiver

must be accompanied by a certificate, signed by the debt agreement administrator

that he, or she, has reasonable grounds to believe that the debtor is likely to

be able to discharge the obligations created by the agreement as and when they

fall due.[68]

This does not always prevent debt agreements that could cause a debtor undue

financial hardship.

Item 20 amends the Bankruptcy Act to insert

another circumstance in which a debtor cannot give the Official Receiver a debt

agreement proposal, being if the total payments under the agreement exceed the

debtor’s income by a certain percentage.[69]

Item 21 provides that the Minister can determine this percentage by

legislative instrument.[70]

The Minister cannot delegate this legislative instrument

making power (item 19).

Commencement

and application

These provisions will apply to debt agreement proposals

given to the Official Receiver six months after Royal Assent (item 22).

Part 5—Undue

hardship to debtor

Item 23 provides that the Official Receiver can

refuse to accept a debt agreement proposal for processing if the Official

Receiver reasonably believes that complying with the debt agreement would cause

undue hardship to the debtor.[71]

The Bankruptcy Act does not define hardship or undue

hardship. Instead, it is up to the Court or the Official Trustee to

determine on a case by case basis.[72]

Commencement

and application

This amendment will apply to debt agreement proposals

given to the Official Receiver six months after Royal Assent (item 24).

Part 6—Other

matters

Item 25 inserts a new definition into section 185

for a proposed administrator, in relation to a debt agreement

proposal.[73]

Opaqueness of a proposed administrator’s relationships can

be problematic if an affected creditor under the proposed debt agreement is a

related entity of the proposed administrator.[74]

Section 5 of the Bankruptcy Act defines the term related

entity, in relation to a person, as any of the following:

(a) a relative of the

person

(b) a body corporate of

which the person, or a relative of the person, is a director

(c) a body corporate

that is related to the body corporate referred to in paragraph (b)

(d) a director, or a

relative of a director, of a body corporate referred to in paragraph (b) or (c)

(e) a beneficiary under a

trust of which the person, or a relative of the person, is a trustee

(f) a relative

of such a beneficiary

(g) a relative of the

spouse, or de facto partner, of such a beneficiary

(h) a trustee of a trust

under which the person, or a relative of the person, is a beneficiary

(i) a member

of a partnership of which the person, or a relative of the person, is a member.

Item 33 of Part 6 in Schedule 1 to the Bill amends

the Bankruptcy Act to require the proposed administrator to record

details of any broker or referrer information and to declare whether an

affected creditor is also a related entity.[75]

The Official Receiver will be required to send this information to affected

creditors (item 38), permitting them to review an administrator’s

relationships and help to ensure that the voting process (on whether to accept

a debt agreement proposal) is ‘fair and transparent’.[76]

To avoid potential conflicts of interest, item 39 of

Part 6 in Schedule 1 to the Bill provides that the Official Receiver should not

request a vote from a proposed administrator that is an affected creditor or

from a related entity to the proposed administrator.[77]

To ensure that the results of a vote are not impacted by

potential conflicts of interest, item 40 amends the acceptance rule to

require the Official Receiver to disregard any votes received from the proposed

administrator or related entity of the proposed administrator.[78]

The conflict of interest concerns underlying amendments in

items 39 and 40 do not apply where a debtor proposes to self-administer

their own debt agreement and an affected creditor is a related entity.

Item 41 creates a criminal offence where a proposed

administrator gives, agrees, or offers to give an affected creditor an

incentive for voting a certain way on a debt agreement proposal.[79]

The maximum penalty is three months imprisonment.[80]

The Explanatory

Memorandum states that ‘this punishment is appropriate to deter fraudulent

conduct in the financial sector which can have severe consequences for both

affected creditors and debtors’.[81]

Schedule 2—Debt

agreements

The amendments in Schedule 2 to the Bill set standards for

the operation of debt agreements, covering their length, and arrangements for

termination and voiding. The amendments also cover an administrator’s duties in

their administration of debt agreements.

Part 1—Length

of debt agreements

There is currently no limit on the proposed timeframe for

making payments under a proposed debt agreement. Item 1 inserts proposed

subsection 185C(2AA) into the Bankruptcy Act so that a debt

agreement proposal must not provide that the debtor may make payments under the

agreement for a period longer than three years. This three year timeframe

aligns with the length of income contributions under bankruptcy. This

limitation does not prevent a debt agreement from running longer than the

proposed timeframe, if the obligations have not been discharged three years

after the day the agreement was made.[82]

Item 2 inserts a reference to this amendment into

paragraph 185E(2)(a) to ensure that the Official Receiver does not accept a

debt agreement proposal for processing if it proposes to make payments under

the agreement for a timeframe longer than three years.

Under subsection 185M(1) of the Bankruptcy Act, a

debtor or creditor who is a party to a debt agreement may give the Official

Receiver a written proposal to vary the debt agreement. Item 3 ensures debtors

and creditors under existing debt agreements cannot propose a variation if the

timeframe for making payments under the agreement would be longer than three

years from the day the agreement was made.[83]

Item 4 of Part 1 in Schedule 2 to the Bill inserts a reference to this

amendment into subsection 185M(2) to ensure that the Official Receiver does not

process the variation if the proposed timeframe for making payments would be

longer than three years from the day the agreement was made.

Commencement

and application

The amendments under items 1 and 2 apply to debt

agreement proposals given to the Official Receiver on or after six months after

Royal Assent. The amendments relating to debt agreement variations (under items

3 and 4) will apply in relation to debt agreements that come into force on

or after six months after Royal Assent where the debt agreement proposals were

given on or after that commencement.

Part 2—Proposals

to vary debt agreements

The proposed amendments outlined above mean that a debtor

cannot give the Official Receiver a debt agreement proposal if the total

payments under the agreement exceed the debtor’s income by a certain

percentage,[84]

with the percentage determined by the Minister.[85]

Limiting the proposed timeframe for making payments under a debt agreement to

three years,[86]

allows the Minister to calibrate the percentage to a three-year payment

schedule.

Key issue—Sustainability

As stated above, the Bankruptcy Act requires a debt

agreement proposal given to the Official Receiver to be accompanied by a

certificate, signed by the debt agreement administrator that he, or she, has

reasonable grounds to believe that the debtor is likely to be able to discharge

the obligations created by the agreement as and when they fall due.[87]

No such requirement exists in relation to a variation proposal made under

section 185M of the Bankruptcy Act. Item 7 inserts proposed

subsections 185M(1E) and (1F) into the Bankruptcy Act so that a

certificate in equivalent terms is provided where a proposal is made to vary a

debt agreement. The variation proposal is required to meet the same percentage

constraint as the initial debt agreement proposal.

Item 9 inserts proposed amendments which provide:

- the

Official Receiver can refuse to accept a debt agreement variation proposal if he

or she reasonably believes that complying with the debt agreement (as proposed

to be varied) would cause undue hardship to the debtor[88]

- if

the Official Receiver decides not to proceed with a variation proposal (as

above), he or she must give notice of the decision and the reasons for it,[89]

and the debtor or affected creditors may apply to the Administrative Appeals

Tribunal for a review of the decision.[90]

Key issue—Conflicts

of interest

Item 10 deals with conflicts of interest that may

arise if the debt agreement administrator is a creditor in a debt agreement

variation proposal. It inserts amendments which relate to the procedures

for dealing with proposals to vary debt agreements: the Official Receiver

should not request a vote on a debt agreement variation proposal from a debt

agreement administrator that is an affected creditor,[91]

or, who on becoming an affected creditor, is a related entity of the

administrator.[92]

These restrictions do not apply if the debtor is self-administering their debt

agreement.[93]

Currently section 185MC sets out the rule for acceptance

of a proposal to vary a debt agreement. Item 11 inserts proposed

subsections 185MC(1A) and (1B) into the Bankruptcy Act to amend the acceptance

rule by requiring the Official Trustee to disregard any votes from the proposed

administrator or a related entity of the proposed administrator.[94]

Key issue—Valuable

consideration

Item 12 creates a criminal offence where a debt

agreement administrator gives, agrees or offers to give to an affected

creditor, any valuable consideration with a view to securing the affected

creditor’s acceptance or non-acceptance of the proposal to vary a debt

agreement.[95]

The maximum penalty for contravention of this subsection is three months

imprisonment, with the Explanatory

Memorandum stating that ‘[t]his punishment is appropriate to deter

fraudulent conduct in the financial sector which can have severe consequences

for both creditors and debtors’.[96]

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Bill apply

to debt agreements which are proposed six months after Royal Assent.

Part 3—Proposals

to terminate debt agreements

Items 14 and 15 deal with conflict of

interest concerns in the voting of a proposal to terminate a debt agreement.[97]

The provisions mirror those in items 10 and 11 in Part 2 of Schedule 2 as

discussed above.

Item 16 creates a criminal offence where a debt

agreement administrator gives, agrees or offers to give to an affected

creditor, any valuable consideration with a view to securing the affected

creditor’s acceptance or non-acceptance of the proposal to terminate a debt

agreement.[98]

The maximum penalty for the offence is three months imprisonment.

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 3 of Schedule 2 to the Bill apply

to debt agreements proposed six months after Royal Assent.

Part 4—Court

orders to terminate debt agreements

Currently, the Court can make an order to terminate a debt

agreement in certain circumstances, including:

- failure

of a debtor to carry out the term of the agreement, or

- if

carrying out the agreement would cause injustice or undue delay to the

creditors or debtor, or

- if

it is in the creditors’ interests to do so.[99]

Item 18 amends the Bankruptcy Act to expand

the list of reasons for which the Court may make an order to terminate a debt

agreement. The additional reasons are that the administrator has contravened

any of the proposed subsections which make it an offence for the agreement

administrator to give, agree or offer to give to an affected creditor, any

valuable consideration (for a vote on a proposal to accept, vary or terminate a

debt agreement) with a view to securing the affected creditor’s acceptance or

non-acceptance of the proposal.[100]

Part 5—Voiding

debt agreements

Section 185T of the Bankruptcy Act provides that a

debtor, creditor or the Official Receiver may apply to the Court for an order

declaring that all, or a specific part, of a debt agreement is void. This is

currently limited to two circumstances:

- if

all or part of the debt agreement was not made in accordance with, or in

compliance with Part IX of the Bankruptcy Act, or

- if

the statement of affairs lodged with the debt agreement omitted a material

particular or was incorrect.[101]

If an application under section 185T is successful, the

Court may make an order to declare a debt agreement void.[102]

In that case, the Court may also make ancillary orders including an order

directing a person to pay another person compensation.[103]

This enables the Court to put a debtor into a similar position as they would

have been had the debt agreement not been entered into.

Items 19–21 in Part 5 of Schedule 2 to the Bill

amend subsection 185T(2) to extend the grounds on which an application can be

made to the Court for an order declaring that a debt agreement is void to

include instances where an administrator:

- has

committed a breach of duty in relation to the agreement, or

- has

breached a condition in an instrument under registration provisions either as

an individual or as a company, or

- has

breached a condition imposed under registration requirements.[104]

These amendments ensure that a debtor can be put into a

similar position they would have been had the debt agreement not been entered

into. This includes removing the debtor’s name from the NPII, awarding damages,

and declaring that the debtor has not committed an act of bankruptcy.

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 5 of Schedule 2 to the Bill apply

to debt agreements that come into force six months after Royal Assent.

Part 6—Debt

agreement administrators to refer evidence of offences

Section 19 of the Bankruptcy Act, sets out the

duties of the trustee of the estate of a bankrupt including, amongst other

things, the duty to consider whether the bankrupt has committed any offences

under the Bankruptcy Act, and if so, the duty to refer any

evidence of the offence to the Inspector-General or to relevant law enforcement

authorities.[105]

Item 23 amends section 185LA of the Bankruptcy

Act to extend the duties of a debt agreement administrator to reflect those

duties conferred on a bankruptcy trustee, which are discussed above.[106]

Commencement

and application

The amendments made in Part 6 of Schedule 2 to the Bill apply

in relation to debt agreements that come into force six months after Royal

Assent.

Part 7—Reporting

requirements for debtors in arrears

Section 185LB of the Bankruptcy Act requires the administrator

of a debt agreement to notify creditors of a three-month arrears default by a

debtor in certain circumstances. This obligation applies regardless of the

amount in arrears.

Items 25–27 amend subsection 185LB(3) of the Bankruptcy

Act to increase the threshold by which an administrator is obliged to

report a three-month arrears default. The proposed amendments provide that

administrators are only required to report to creditors if:

- the

value of the arrears exceeds either 20 per cent of the payment due for the

period or $300, whichever is higher, or

- the

value of all due payments was $300 or less, and no payment was made in that

period.[107]

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 7 of Schedule 2 to the Bill apply

in relation to debt agreements that come into force six months after Royal

Assent.

Part 8—Alignment

of offences

Separate

bank accounts

Schedule 2 to the Bankruptcy Act is the Insolvency

Practice Schedule (Bankruptcy). One of the primary objects of the Schedule is

to regulate the administration of regulated debtors’ estates consistently,

unless there is a clear reason to treat a matter that arises in relation to a

particular kind of estate differently.[108]

In particular, Division 65 of Schedule 2 deals with funds handling.

The purpose of the amendments in Part 8 of Schedule 2 to

the Bill is to align the provisions relating to debt agreements with those in

Schedule 2.[109]

Subsection 185(LD)(1) of the Bankruptcy Act requires a debt agreement

administrator who is the administrator of one or more debt agreements to pay

all monies received from debtors into a single trust account in the debt

agreement administrator’s own name. Item 29 inserts proposed

subsection 185LD(2A) into the Bankruptcy Act to prohibit debt

agreement administrators from paying any money out of that bank account, other

than for purposes of administration of the debt agreement, in accordance with

the Bankruptcy Act, or by direction of the Court.

Failure to comply with provisions relating to payments

into and out of administration accounts gives rise to an offence of strict

liability, the maximum penalty for which is 50 penalty units.[110]

Item 30 inserts a new strict liability offence provision of 50 penalty

units for contravention of existing subsections relating to maintenance of a

separate bank account for debt agreement money and payments made to the bank

account, and the proposed amendment relating to payments made out of said bank

account.[111]

The Explanatory

Memorandum states that ‘[s]trict liability offences are appropriate ... as it

is necessary to strongly deter misconduct that can have serious consequences

for affected parties’.[112]

Sufficient

records

Division 70 of Schedule 2 to the Bankruptcy Act

provides that bankruptcy trustees and debt agreement administrators are

required to keep sufficient records as are necessary to give a full and correct

account of either the administration of the estate or the administration of the

debt agreement, respectively, and to make such records available to the

Inspector-General if so required. Failure to comply with these provisions

currently attaches a strict liability offence of five penalty units for

bankruptcy trustees.[113]

Item 31 aligns existing section 185LE with Schedule 2 in that it creates

an offence of strict liability with a maximum penalty of five penalty units for

debt agreement administrators, consistent with the provision relating to

bankruptcy trustees.[114]

As an alternative to prosecution, a penalty can be imposed

through an infringement notice. The amount payable in respect of an

infringement notice for a breach of a specific section of the Bankruptcy Act

is set out in table form in subsection 277B(2). Item 32 amends the table

so that a breach of the requirement to keep sufficient records and make the

records available for audit can, where appropriate, be addressed by way of an

infringement notice with an amount payable to the value of one penalty unit.

This aligns with the penalty amounts set out for the equivalent section

relating to trustees.

Commencement

and application

The amendment in item 29, prohibiting money to be

paid out of the trust account in certain circumstances, will apply in relation

to debt agreement proposals that come into force on, after, or were in force

immediately before the period six months after Royal Assent. As noted in the Explanatory

Memorandum, ‘[t]he retrospective application of this duty reflects the

seriousness of breaching it’.[115]

Items 30, 31 and 32 will apply in relation to debt agreements that come

into force on or after six months after Royal Assent.

Part 9—Time

for submitting annual returns

Currently, section 185LEA provides that a debt agreement

administrator must give the Inspector-General an annual return detailing

information on active debt agreements managed by the administrator within 35

days after the financial year. The corresponding deadline for registered

bankruptcy trustees is 25 business days.[116]

Item 34 amends section 185LEA of the Bankruptcy

Act so that the applicable deadline for annual return submissions for debt

agreement administrators is reduced to 25 business days after the end of the financial

year.

Commencement

and application

The amendment made in Part 9 of Schedule 2 to the Bill applies

in relation to financial years ending six months after Royal Assent.

Schedule 3—Registered

debt agreement administrators

The amendments in Schedule 3 to the Bill modify the

standards that registered debt agreement administrators must satisfy.

Part 1—Applications

for registration

Insurance

Registered bankruptcy trustees are required to take out

professional indemnity insurance and fidelity insurance to qualify for

registration.[117]

There is no current similar requirement for debt agreement administrators.

Items 6–13 insert provisions that require debt

agreement administrators to obtain adequate and appropriate professional

indemnity and fidelity insurance, in order to have their applications for

registration and renewal of registration approved by the Official Receiver.

Section 185 provides definitions for Part IX of the Bankruptcy

Act. Item 1 of Part 1 in Schedule 3 to the Bill inserts proposed

definitions of adequate and appropriate fidelity insurance and adequate

and appropriate professional indemnity insurance into that section. Item

2 provides that the Inspector-General may determine, in a legislative

instrument, what constitutes adequate and appropriate insurance.[118]

This aligns with the equivalent provision for bankruptcy trustees.[119]

Interview

To become a registered bankruptcy trustee, a person must

lodge an application with the Inspector-General, who will then convene a

committee to consider the application. The committee must interview the

applicant and decide within 45 business days after interviewing the applicant whether

the applicant should be registered as a trustee or not.[120]

Item 3 amends the Bankruptcy Act to require

the Inspector-General to interview applicants for debt registration ‘as soon as

practicable after receiving the application’.[121]

Item 4 amends the Inspector-General’s deadline for making a decision to

45 business days after the date of interview (rather than 60 days after

receiving the application).[122]

These provisions are designed to align the obligations for

the assessment of registrations for debt agreement administrators and

bankruptcy trustees.

Evidence

Currently, subsection 186C(2) of the Bankruptcy Act

sets out the matters about which the Inspector-General must be satisfied in

deciding whether to approve the registration of a debt administrator. Items

5 and 6 expand the list of matters to include:

- written

evidence that the applicant has taken out adequate and appropriate professional

indemnity insurance and fidelity insurance[123]

- the

applicant is a fit and proper person.[124]

These requirements align with the equivalent provisions

for bankruptcy trustees.[125]

Items 8–12 contain similar provisions for

registration applications by companies. Item 12 requires the company

applicant to be a fit and proper person, and each director of the company to be

a fit and proper person, in order for the Inspector-General to approve an

application for registration as a debt agreement administrator.[126]

Registration

renewal

Currently, the Inspector-General must approve an

individual debt agreement administrator’s application for registration renewal.[127]

The corresponding registered bankruptcy trustee renewal system imposes a

restriction: a trustee’s registration must not be extended if they owe more

than $500 (being the current prescribed amount) of notified estate charges.[128]

To align with the equivalent provisions for registration

renewal for bankruptcy trustees, item 7 repeals and replaces subsection

186C(3) of the Bankruptcy Act to require the Inspector-General to

approve an application for debt agreement administrator registration renewal if,

amongst other things, there is evidence of adequate and appropriate insurance

and the applicant does not owe more than the prescribed amount of notified

estate charges. Proposed subsection 186C(5A) which is inserted

by item 13 of Part 1 in Schedule 3 to the Bill provides that a person

owes a notified estate charge if:

- the

person owes either a charge under the Bankruptcy (Estate

Charges) Act 1997 or a penalty under section 281 (late payment penalty)

under the Bankruptcy Act, and

- the

Inspector-General has notified the person of the unpaid estate charge at least

one month and 10 business days before the person’s registration as a debt

agreement administrator ceases to be in force.

Note that, unlike the requirement for bankruptcy trustee

registration renewal, any amount of notified estate charges owing applies to

debt agreement administrator renewals.

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 1 of Schedule 3 to the Bill apply

in relation to applications for registration and renewal of registration as a

debt agreement administrator made on or after six months after Royal Assent.

Part 2—Conditions

of registration

Section 105-1 of Schedule 2 to the Bankruptcy Act

provides the Minister with the power to create practice standards for

registered bankruptcy trustees. Currently the Minister has no power to set

industry standards for registered debt agreement administrators.

Items 16–18 provide that the registration of

individual and company debt agreement administrators is subject to conditions

determined in a legislative instrument.[129]

The Minister will be given the power to make the associated legislative

instruments for the purposes of determining the conditions.[130]

Subsection 10(1) currently provides that the Minister may

delegate any or all of the Minister’s powers under the Bankruptcy Act,

other than the power of delegation. Item 15 amends subsection 10(1) to

provide that the Minister cannot delegate the legislative instrument-making

powers which are created as set out above.[131]

Existing subsection 186H(1) provides that a debt agreement

administrator may apply to the Inspector-General to have any conditions on

their registration changed or removed. Item 19 inserts proposed

subsection 186H(1A) into the Bankruptcy Act to ensure that

conditions determined in a legislative instrument (under items 16 and 17)

cannot be removed upon application by a debt agreement administrator.[132]

Commencement

and application

Item 20 provides that the amendments in Part 2 of

Schedule 3 to the Bill apply to all registered debt agreement administrators

regardless of whether they became registered before or after six months after

Royal Assent.

Part 3—Ongoing

obligation to maintain insurance

Item 21 inserts proposed Subdivision

BA—Insurance into Division 8 of Part IX of the Bankruptcy Act. Within the

new Subdivision, proposed section 186HA mandates that registered debt

agreement administrators must maintain adequate and appropriate professional

indemnity and fidelity insurance, and that failure to do so amounts to an

offence. In the case of intentional or reckless failure, a penalty of 1,000

penalty units will apply;[133]

otherwise, failure to comply is considered a strict liability offence with a

penalty of 60 penalty units. Registered bankruptcy trustees are subject to

similar provisions.[134]

Commencement

and application

The obligation for debt agreement administrators to

maintain insurance applies to registered debt agreement administrators who

applied for registration on or after six months after Royal Assent (item 22).

Part 4—Cancellation

of registration

Section 186K of the Bankruptcy Act sets out the

circumstances in which the Inspector-General may cancel an individual’s

registration as a debt agreement administrator. The equivalent provisions for

company debt agreement administrators are set out in section 186L.

Items 23 and 24 amend those sections to expand the

grounds under which the Inspector-General may request a written explanation

from the debt agreement administrator to justify their continued registration.[135]

These include:

- a

failure to have adequate and appropriate professional indemnity or fidelity

insurance, or

- the

administrator (or company or director of the company) is not a fit and proper

person.

These amendments will enable the Inspector-General to

cancel a debt agreement administrator’s registration if:

- the

debt agreement administrator does not respond to the written request within 28

days, or

- an

explanation is received, but the Inspector-General is not satisfied with it.

Commencement

and application

The obligation for debt agreement administrators to

maintain insurance and be a fit and proper person applies to registered debt

agreement administrators who applied for registration six months after Royal

Assent (item 25).

Part 5—Trust

accounts

Subsection 186LA(1) of the Bankruptcy Act sets out

the conditions under which the Inspector-General may obtain information about

debt agreement administration trust accounts. Currently, if the

Inspector-General reasonably believes that a debt agreement administrator is

misusing trust money, he or she is empowered to give notice to the bank

requiring that specified information about the relevant account is provided in

the manner and within the time specified in the notice. Item 26 inserts proposed

subsection 186LA(1A) into the Bankruptcy Act empowering the

Inspector-General to give notice to the bank to obtain information if the

Inspector-General ‘reasonably suspects’ that the debt agreement administrator

has:

- contravened

a provision of the Bankruptcy Act

- failed

to properly carry out the duties of an administrator in relation to the debt

agreement or

- contravened

a condition of the person’s registration as a registered debt agreement

administrator.[136]

Commencement

and application

The amendments in this part will apply to debt agreements

that come into force on or after six months after Royal Assent.

Part 6—Functions

of Inspector-General

Section 12 of the Bankruptcy Act sets out the

functions of the Inspector-General. The Explanatory

Memorandum states that the Inspector-General’s powers to investigate and

inquire into a debt administrator’s conduct, applies only once a debt agreement

is made.[137]

However, subsection 12(1BA) states:

[t]he Inspector‑General may make an inquiry or

investigation under paragraph (1)(b), (ba), (bb) or (bc) at any time,

whether before or after the end of the bankruptcy, composition, scheme or

agreement or administration concerned

The reference to paragraph (bb) is a reference to the

conduct of an administrator of a debt agreement.

Item 28 inserts proposed paragraph 12(1)(bd)

into the Bankruptcy Act to put beyond doubt that the Inspector-General’s

investigation and inquiry powers extend to any conduct of a debt

agreement administrator. This permits the Inspector-General to investigate or

inquire into the conduct of a debt agreement administrator even if an agreement

is not ultimately made, and into a debt agreement administrator’s advertising

or other methods used to attract debtors.

Commencement

and application

The amendments in Part 6 of Schedule 3 to the Bill provide

that the Inspector-General will be able to investigate the conduct of a debt

agreement administrator that has occurred on or after six months after Royal

Assent, regardless of whether the administrator was registered before, on or

after then.

Other provisions

Schedule 4—Registered

trustees

The amendments in Schedule 4 are technical amendments.

They also clarify that the Minister’s power to make rules under the Insolvency

Practice Rules extends to registered trustees administering debt agreements.

Item 1 moves the Minister’s inability to delegate

its power to make Insolvency Practice Rules by legislative instrument from

subsection 105-1(6) in Schedule 2 of the Bankruptcy Act to subsection

10(1).

To ensure that the Insolvency Practice Rules reflect

similar industry conditions for registered bankruptcy trustees administering

debt agreements, item 2 clarifies that the Minister’s power to amend the

Insolvency Practice Rules extends to amendments for the purposes of imposing

conditions on registered bankruptcy trustees administering debt agreements.[138]

Commencement

and application

The amendments contained in this schedule will apply to a

person who becomes a registered trustee, or registered trustees who are

registered immediately before, six months after Royal Assent.

Schedule 5—Unclaimed

money

The amendments in Schedule 5 to the Bill modify the

requirements for registered personal insolvency practitioners to pay unclaimed

moneys to the Commonwealth, as well as the process for persons to apply for

unclaimed moneys.

A bankruptcy is annulled if the trustee is satisfied that

all the bankrupt’s debts have been paid in full.[139]

If money is paid to the Official Receiver because the creditor cannot be found

or identified, it is taken to be paid in full to the creditor. Currently, if

money is paid to the Official Receiver, a person who claims to be entitled to

any moneys is required to make an administrative claim to the Court.[140]

Item 1 amends subsection 153A(5) of the Bankruptcy

Act to enable a person to make an administrative claim to the Official

Receiver rather than the Court. The Explanatory

Memorandum notes that, in many instances, the costs of seeking a court

order would exceed the amount of money that is being sought. Item 4 repeals

existing subsections 254(3) and (4) and inserts proposed subsections

254(3)–(9) which set out the processes for making, assessing and giving

notice of the outcome of an application as well as a mechanism for review of

the Official Receiver’s original determination by the Court.

If the trustee of a deceased person’s estate is satisfied

that all the debts of the estate have been paid in full, the order for the

administration of the estate under Part IX of the Bankruptcy Act is

annulled.[141]

Item 2 enables a person to make an administrative claim to the Official

Receiver rather than the Court.[142]

A trustee or debt agreement administrator must pay to the

Commonwealth any unclaimed dividends or moneys. The requirement for a debt

agreement administrator to pay unclaimed dividends or moneys should only apply

where the debt agreement administrator has identified the person entitled to

the moneys.

Item 3 ensures that this requirement—to pay any

unclaimed dividends or money to the Commonwealth—applies where the person

entitled to the money has been identified but is unable to be located despite

the debt agreement administrator making ‘all reasonable efforts’.[143]

Application

and saving provisions

Item 5 provides that:

- a

person can apply to the Official Receiver for unclaimed moneys paid to the

Commonwealth on or after six months after Royal Assent

- a

person can apply to the Official Receiver for unclaimed moneys paid to the

Commonwealth before six months after Royal Assent, where an application had not

previously been made to the Court and

- where

a person has applied to the Court for an order for moneys owing before six

months after Royal Assent, the subsections as in force immediately before six

months after Royal Assent shall continue to apply.

Appendix 1: Personal insolvencies, Australia

Figure 1: Personal insolvencies, Australia 1986–87 to 2016–17

Source: AFSA, ‘Time series’, AFSA

website.

Appendix 2: Formal options for insolvency

Table A1: Eligibility

|

|

Bankruptcy

|

Debt agreements

|

Personal insolvency

agreements

|

|

Australian connection

|

Must have a residential

or business connection.

|

No residential or

business connection required.

|

Must have a residential

or business connection.

|

|

Previous insolvency

|

While previous insolvency

does not by itself make a person in eligible, the Official Receiver may not

accept the petition if the debtor was previously bankrupt and some other

conditions are met.

|

Must not have been a

bankrupt, proposed a personal insolvency agreement or made a debt agreement

in the previous 10 years.

|

Must not have proposed

another personal insolvency agreement in the previous six months.

|

|

Income threshold

|

No

|

A person cannot propose a

debt agreement if their after tax income for the year is more than $83,756.40.

|

No

|

|

Asset threshold

|

No

|

A person cannot propose a

debt agreement if their divisible property is more than $111,675.20.

|

No

|

|

Debt threshold

|

No

|

A person cannot propose a

debt agreement if their unsecured debts are more than $111,675.20.

|

No

|

Source: AFSA, ‘Compare

the formal options’, AFSA website.

Table A2: Income, employment and trade

|

|

Bankruptcy

|

Debt agreements

|

Personal insolvency

agreements

|

|

Payments from income

required?

|

Yes, mandatory payments

required if income exceeds the statutory threshold—these are on the AFSA

website.

|

Yes, if the terms of the agreement

require payments from income—this occurs in most cases.

|

Only if the terms of the

agreement require payments from income.

|

|

Ability to continue to

operate a business

|

It depends on the nature

of the business and if the trustee sells the business assets. Key points

include:

- when a partner becomes bankrupt

it dissolves an existing partnership

- if trading under a business or

assumed name after the date of bankruptcy, a bankrupt must disclose their

bankruptcy to people dealing with the business. This will include bankrupts

trading alone or jointly.

|

Yes, unless the terms of

the agreement provide otherwise. If trading under a business name or assumed

name (whether alone or in partnership) the debt agreement must be disclosed

to all people dealing with the business.

|

Yes, if the agreement

allows for the debtor to continue to operate the business.

|

|

Ability to be a

director of, or otherwise manage, a corporation

|

No

|

Yes

|

Not until the terms of

the agreement are fully complied with.

|

|

Other employment

restrictions

|

Professional bodies

and/or trade associations may have certain conditions of membership for the

duration of the bankruptcy. There may be restrictions on holding some

statutory positions during the period of bankruptcy.

|

Professional bodies

and/or trade associations may have certain conditions of membership for the

duration of the agreement. There may be restrictions on holding some

statutory positions during the period of the agreement.

|

Professional bodies

and/or trade associations may have certain conditions of membership for the

duration of the agreement. There may be restrictions on holding some

statutory positions during the period of the agreement.

|

Source: AFSA, ‘Compare

the formal options’, AFSA website.

Table A3: Assets

|

|

Bankruptcy

|

Debt agreements

|

Personal insolvency

agreements

|

|

Ability to retain

assets

|

No, unless it is exempt

property (for example household furniture, tools of trade up to a certain

value).

|

Yes, unless terms of the

agreement provide otherwise.

|