Bills Digest no. 69, 2017–18

PDF version [356KB]

Owen Griffiths

Law and Bills Digest Section

2 February 2018

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Background

Issues during 2016 federal and ACT

elections

Figure 1: example of bulk SMS text

messages sent on election day

Joint Standing Committee on Electoral

Matters

Electoral and Other Legislation

Amendment Bill 2017

Save Medicare websites

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committee on Legal

and Constitutional Affairs

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Scope of the offences

Freedom of expression

Freedom of political communication

Satire, academic and artistic

purposes

Figure 2: screenshot from Centrelink

Fail - Honest Government Advert video (The Juice Media)

Justification for new offences

Injunctions

Figure 3: extract of The NBN

tagline, translated (The Gruen Team)

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 13

September 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Attorney-General

Commencement: The

day after Royal Assent.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at February 2018.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a

Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend the Criminal Code Act

1995 (Cth) (Criminal Code) to introduce two offences for persons

who engage in conduct which results in a representation that the person is, or

is acting on behalf of, a Commonwealth body. The Bill also allows affected

persons to seek injunctions to prohibit or prevent this conduct under the Regulatory Powers

(Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) (Regulatory Powers Act).

Background

Issues

during 2016 federal and ACT elections

During the 2016 federal election, the Australian Labor

Party (ALP) campaign included a claim that the Coalition intended to privatise

Medicare. This claim was dubbed ‘Mediscare’ by the media and was judged to have

assisted the ALP position during the election period.[1]

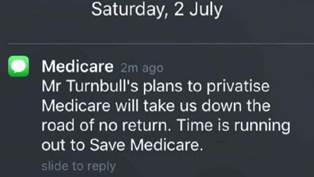

Aspects of the ‘Mediscare’ campaign included the distribution of cardboard

flyers containing messages which resembled Medicare cards, voice mail messages

and bulk SMS text messages.[2]

In particular, the bulk SMS text messages, sent by the

Queensland Labor Party on election day, appeared under the heading ‘Medicare’

(see Figure 1 below). Concerns were raised that the sender of the text messages

was not clearly identified and that the text messages could be confused as

originating from Medicare itself. A Queensland Labor Party spokesman confirmed

it was the origin of the text messages, but stated that the ‘message was not

intended to indicate that it was a message from Medicare, rather to identify

the subject of the message’.[3]

However, in his election night victory speech, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull

described the text messages as an ‘extraordinary act of dishonesty’ and

considered there was ‘no doubt the police will investigate’.[4]

Figure 1: example of bulk SMS text messages sent on election day

Source: D Lewis (@dlewis89), ‘Has anyone else received

this text message? Is Labor pretending to be Medicare?’, tweet, 2 July 2016, https://twitter.com/dlewis89/status/749077501276622848.

The matter was referred to and evaluated by the Australian

Federal Police (AFP), but no Commonwealth offences were identified.[5]

Currently, the Criminal Code makes it an offence for a person to impersonate

or falsely represent themselves to be a Commonwealth official, but not a

Commonwealth body.[6]

During the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) election in

2016, the Australian Government Solicitor wrote to the ACT Labor Party demanding

it cease distributing political pamphlets which resembled Medicare cards as the

cards were a breach of copyright.[7]

The ACT Labor Party apologised and agreed to withdraw the cards.[8]

Joint

Standing Committee on Electoral Matters

In the first interim report for its inquiry

into the 2016 Federal Election, the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral

Matters (JSCEM) considered concerns raised that ‘electoral materials were

disseminated by individuals or organisations claiming to be a Commonwealth

entity’.[9]

It noted that, when the AFP considered the matter of the ‘Mediscare’ text

messages, the AFP had found that there was no scope for a criminal prosecution because

there was no law against impersonating, or purporting to act on behalf of, a

Commonwealth entity.[10]

The JCSEM concluded that ‘impersonating, or purporting to act on behalf of, a

Commonwealth officer or an entity is unacceptable and that steps should be

taken to ensure that neither occurs in future’.[11]

It recommended that the JSCEM ‘conduct further inquiry and make recommendations

in early 2017 regarding the issues of impersonating a Commonwealth officer and

Commonwealth entity’.[12]

However, the introduction of the proposed amendments to the Criminal Code

appears to have pre-empted further inquiry into this issue.[13]

Electoral

and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017

The proposed offences contained in the Bill were initially

part of the Electoral

and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 (Electoral Bill) introduced into

the House of Representatives on 30 March 2017. However, during the

consideration in detail stage of the debate, the Government amended the

Electoral Bill to remove the schedule concerning the criminalisation of

impersonating a Commonwealth body. The Minister for Trade, Tourism and

Investment, Steven Ciobo, did not give a reason for the amendment but noted

that ‘the government remains committed to legislating to criminalise the

impersonation of a Commonwealth entity’ and that separate legislation would

deal with this issue.[14]

The Electoral Bill, as amended, was passed.[15]

Save

Medicare websites

In November 2016, it was reported that the Australian

Government Solicitor (AGS) on behalf of the Department of Human Services (DHS)

wrote to Mark Rogers who operates a website called savemedicare.org as well as an associated Facebook

subdomain and a Twitter account.[16]

The AGS letter reportedly stated that Mr Rogers’ use of the Medicare logo on

the website was ‘misleading or deceptive and infringes [DHS’s] copyright in the

MEDICARE logo’. It demanded Mr Rogers remove all instances of the Medicare

logo and branding, any ‘deceptively similar branding’ and cancel the domain

name of the website, Facebook subdomain, and Twitter handle.[17]

Following media attention, a Getup

petition and a question to Prime Minister Turnbull during Question Time,[18]

the AGS reportedly clarified that DHS had no intention of commencing legal

proceedings against Mr Rogers.[19]

The ALP operates a similarly named website savemedicare.org.au. Media reports

indicate that the AGS also sent a letter to the ALP requesting the Medicare

logo be removed from the website, however this request was rejected by Maurice Blackburn,

the law firm representing the ALP.[20]

Committee

consideration

Senate Standing

Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs

The provisions of the Bill were referred

to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs for inquiry

and report. The inquiry

received seven submissions and no public hearings were held. In the inquiry

report, tabled on 13 November 2017, the majority of the Committee

recommended the Bill be passed.[21]

The majority report of the Committee stated:

The committee has carefully considered the information

provided by submitters—that the proposed offence may violate Australia's human

rights obligations, that the offence may go beyond its stated intention, that

there may be unintended consequences such as limiting freedom of speech and

political satire, and that the exemption should be unambiguous.

The committee has weighed these concerns with the fact that

the proposed offences almost mirror the current offences for impersonating a

Commonwealth official, including the form in which the proposed exemption has

been articulated. Additionally, the committee notes that both the Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, and the Human Rights Committee,

reported that it had no scrutiny or human rights concerns. Ultimately, the

committee is of the view that the Bill is both proportionate and necessary and

therefore recommends that the Bill be passed.[22]

Senator Nick McKim, for the Australian Greens, made a

dissenting report which recommended the Bill ‘be opposed by the Senate’.[23]

The dissenting report stated:

The Australian Greens are concerned that the Chair [Senator

Ian Macdonald] has not appropriately responded to and addressed the concerns

raised by the submitters regarding this bill.

The amendments proposed are unnecessary, have not been

sufficiently justified, will unreasonably fetter freedom of political

expression and silence many satirists.[24]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills considered

the Bill and made no comment.[25]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

ALP members of the JSCEM inquiry did not dissent from its

characterisation of impersonating a Commonwealth body as ‘unacceptable’.

Further, ALP members of the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee

did not dissent from the majority report which recommended the Bill be passed.

However, in February 2017, the Shadow Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, was

reported as describing the efforts by the Government to criminalise tactics

like ‘Mediscare’ as ‘the longest dummy spit in Australian political history’.[26]

As noted above, the dissenting report to the Senate inquiry

into the provisions of the Bill outlined that ‘the Australian Greens believe

that this Bill is an unacceptable limitation on freedom of expression and could

potentially have a chilling effect on political communication and satire’.[27]

Position of

major interest groups

The submissions

to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee inquiry into the

provisions of the Bill contain a range of views. A number of submissions

expressed concerns regarding the scope of conduct covered by the new offences,

the potential impact on freedom of expression and the adequacy of the protection

of satirical, academic and artistic activities. Several, such as Electronic

Frontiers Australia, have suggested amendments to the definition of ‘conduct’

to clarify the exclusion of these activities.[28]

In contrast, the Legal Services Commission of South Australia supported the new

offences because of the harm ‘caused by scams where callers claim to represent

Commonwealth Government departments’.[29]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory

Memorandum states the Bill will have ‘no financial impact’.[30]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[31]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR) has

listed the Bill as one which does not raise human rights concerns.[32]

However, the provisions of the Bill were originally part of

the Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 (Electoral Bill). In

relation to this part of the Electoral Bill (prior to its amendment to remove

these provisions) the PJCHR highlighted that proposed subsection 150.1(4) of

the Criminal Code ‘provides that if the commonwealth body is fictitious,

these offence provisions do not apply unless a person would reasonably believe

that the commonwealth body exists’. The PJCHR considered that this ‘appear[ed]

to provide an exception to the relevant offence’. The PJCHR observed that

current subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code provides that ‘a

defendant who wishes to rely on any exception, exemption, excuse, qualification

or justification bears an evidential burden in relation to that matter’. It noted:

Article 14(2) of the [International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights] protects the right to be presumed innocent until proven

guilty according to law. Generally, consistency with the presumption of

innocence requires the prosecution to prove each element of a criminal offence

beyond reasonable doubt. Provisions that reverse the burden of proof and

require a defendant to disprove, or raise evidence to disprove, one or more

elements of an offence, engage and limit this right.[33]

The Minister’s response to the PJCHR clarified:

The Government considers that proposed subsection 150.1(4)

does not create an offence-specific defence. Rather, the condition of 'unless a

person would reasonably believe that the Commonwealth body exists' forms an

element of the offence and the burden of proof for proving that element will

sit with the prosecution. That is, there is no reversal of the onus of proof

with respect to this subsection.[34]

The PJCHR noted that ‘based on the information provided by

the minister, the measure appears to be compatible with the presumption of

innocence’. It recommended that the explanatory materials for the Electoral

Bill be amended to include this information.[35]

A statement to this effect has been included in the Explanatory

Memorandum for the Bill.[36]

Key issues

and provisions

Item 2 inserts new ‘Division 150 – False

representations in relation to a Commonwealth body’ at the end of Part 7.8

of the Criminal Code. This contains two subdivisions.

Subdivision A - Offences contains the offences of

false representations in relation to a Commonwealth body in proposed section

150.1. This includes a primary offence (proposed subsection 150.1(1))

and an aggravated offence (proposed subsection 150.1(2)).

Subdivision B - Injunctions provides that section

150.1 is enforceable under Part 7 of the Regulatory Power Act

(subsection 150.5(1)).

Scope of

the offences

As noted above, the Bill creates both a primary offence and

an aggravated offence. The primary offence in proposed subsection 150.1(1)

provides that a person commits an offence if they engage in conduct which

results in, or is reasonably capable of resulting in, a representation that the

person is a Commonwealth body or acting on behalf of, or with the authority of,

a Commonwealth body. The maximum penalty is two years imprisonment.

Under the Criminal Code offences generally consist of

physical elements (such as undertaking specified conduct) and fault elements

(such as intention, knowledge, recklessness or negligence).[37]

The offence at proposed subsection 150.1(1) does not specify fault elements. Section

5.6 of the Criminal Code sets out the fault elements that apply in such

situations. In this case, the primary offence will occur where:

- a

person intentionally[38]

engages in conduct (for example, sending an email or an SMS)

- the

person is reckless[39]

as to whether their conduct will result in, or is reasonably capable of

resulting in, a relevant false representation

- the

person is not a Commonwealth body and is not acting on behalf of or with the authority

of, the Commonwealth body, and the person is reckless in relation to

this circumstance.[40]

Section 5.4 of the Criminal Code provides that a

person is reckless with respect to a result or a circumstance if:

- he

or she is aware of a substantial risk that the result will occur or the

circumstance exists or will exist and

- having

regard to the circumstances known to him or her, it is unjustifiable to take

the risk.[41]

In relation to this issue, the Explanatory

Memorandum states:

[A] person must be reckless as to whether their conduct will

result in, or is reasonably capable of resulting in, a false

representation...This threshold captures conduct where a person does not

necessarily intend to create the relevant representation, or does not

necessarily believe the circumstance to be false, but where they are aware that

there is a substantial risk that such a representation will occur, or that the

circumstance is false, and it is unjustifiable for them to take that risk. This

threshold is necessary to ensure the offence covers false representations that,

whilst not intentional, are equally capable of undermining public confidence in

the integrity and authority of the Australian Government and are made in

circumstances where the accused is aware of a substantial risk of

misrepresentation.[42]

The aggravated offence in proposed subsection 150.1(2)

contains the same elements as the primary offence, but also requires that the

person engages in the conduct with the intention of:

(i)

obtaining a gain; or

(ii)

causing a loss; or

(iii)

influencing the exercise of a public duty or function.[43]

The maximum penalty is five years imprisonment.

A ‘Commonwealth body’ is broadly defined in proposed

subsection 150.1(7) as a Commonwealth entity, Commonwealth company[44]

or a service, benefit, program or facility for some or all members of the

public that is provided by or on behalf of the Commonwealth. The scope of the proposed

offences is further broadened through proposed subsection 150.1(3) which

provides that, for the purposes of the section, it is immaterial whether the

Commonwealth body exists or is fictitious. However, proposed subsection

150.1(4) provides the offence provisions do not apply ‘unless a person

would reasonably believe that the Commonwealth body exists’.

The Explanatory

Memorandum provides examples of ‘relevant conduct’ for the purposes of the

offences. These include:

- writing

of a letter on the letterhead (or purported letterhead) of a Commonwealth body

- sending

an electronic communication (including an email or text message) imputed to be

from or on behalf of a Commonwealth body

- taking

out an advertisement in the name of a Commonwealth body, or

- issuing

of a publication in the name of a Commonwealth body.[45]

Proposed subsection 150.1(6) provides that extended

geographical jurisdiction (Category C) applies to the offences in the new

section.[46]

Submissions to the Senate Committee inquiry into the Bill

criticised the scope of the proposed offences. In his submission, Professor

Jeremy Gans from the Melbourne Law School considered that the two proposed

offences are ‘significantly broader’ than the existing offences of

impersonating a Commonwealth officer in a number of aspects. He stated:

These extensions are especially significant in combination.

Rather than only criminalising people who deliberately impersonate a

Commonwealth body, proposed s150.1 criminalises any person who is simply aware

of a substantial risk that someone else would or could reasonably have the

impression that the person is acting on behalf of a real or fictitious

Commonwealth body, Commonwealth-controlled corporation or Commonwealth provided

service, benefit, program or facility ... The fundamental problem with s150.1 is

that it criminalises reasonable misunderstandings, rather than deception, in a

context where reasonable misunderstandings (about the role and reach of Australia’s

federal government) are absolutely commonplace (and are widely recognised as

such by all informed people.) Criminalising individuals who must operate within

that context, regardless of their intentions or honesty, is wholly

inappropriate.[47]

Similarly, Australian Lawyers for Human Rights argued that

the Bill exceeds its stated aims:

The new offence would allow imprisonment for up to 2 years

even where there is no intention to deceive and no mens rea[48] involved other than recklessness as to whether or not others may be misled.

The offence would also apply irrespective of whether or not harm has actually

been caused. It applies both in relation to actual Commonwealth entities and

fictitious Commonwealth entities. The proposed section 150.1 permits imprisonment

of persons who do not at any stage intend to persuade others that they are

acting on behalf of a Commonwealth body – and who do not necessarily mislead

anybody, particularly where the body is fictitious (as occurs in the case of

political satire)—but who might be argued to be reckless in that they were

aware of the risk that someone else could form that impression.[49]

Freedom of

expression

In the Bill’s Second Reading Speech, Michael Keenan, the Minister

for Justice, stated that ‘the Bill contains safeguards to ensure that neither

of these offences unduly limits the freedom of expression’.[50]

Despite this assurance, concerns were raised in the submissions to the Senate

Committee inquiry regarding the potential impact of the Bill on freedom of

political communication and conduct undertaken for satirical, academic and

artistic purposes.

Freedom of

political communication

Proposed subsection 150.1(5) provides that without

limiting existing section 15A of the Acts Interpretation

Act 1901 (Cth), the section ‘does not apply to the extent (if any) that

it would infringe any constitutional doctrine of implied freedom of political

communication’.[51]

A freedom of communication in relation to public and political discussion has

been found by Australian courts to be implied in the system of representative

and responsible government established by the Commonwealth Constitution.

The implied freedom operates as a constraint to legislative and executive

power, rather than as an individual right. Laws which burden this implied freedom

of political communication may be invalid if they are found not to be

compatible with the maintenance of the constitutionally prescribed system of

government.[52]

A number of submitters to the Senate inquiry highlighted the

potential burden of the new offences on political communication in Australia.

For example, Electronic Frontiers Australia stated:

Satire particularly is an essential element of public

discourse and can be a powerful tool for highlighting issues and in holding

governments to account. Any attempt by government to suppress satirical

expression is by definition an attack of freedom of expression, and may breach

the implied right to political speech, one of the few constitutional civil

liberties protections available to Australians. [53]

It is unclear to what extent the implied freedom of

political communication will prevent conduct from being treated as an offence

under the provisions of the Bill. The High Court’s interpretation of the

implied freedom of political communication has developed over time and there is

a lack of clarity concerning how it may be applied to offences in the Criminal

Code in the future.[54]

Satire,

academic and artistic purposes

As noted above, proposed subsection 150.1(7) provides

that within the section ‘conduct does not include conduct engaged

in solely for genuine satirical, academic or artistic purposes’.

In his submission, Professor Gans describes this subsection

as ‘lazy drafting’ which is ‘confusing and (perhaps) ambiguous as to which

party will bear the evidential burden on this issue’.[55]

The inclusion of ‘solely’ appears to limit the conduct that would be exempt

from the proposed new offences. Felicity Ruby’s submission to the Senate

inquiry made the point that ‘satire, like that of the Chaser and so many other

examples of Australian culture, is not “solely” for satire but also to stimulate

debate and discussion’.[56]

This point was also emphasised in the submission from

Giordano Nanni who produces a video series called Honest Government

Adverts which satirically impersonate government communications (Figure

2). He questioned:

Who decides what counts as "genuine" satire? There

is a dearth of case law on what "satire" even means in Australia and

it's hard enough to advise on the satire fair dealing exception for copyright

law, let alone when there is 2-5 years' imprisonment at stake.[57]

Mr Nanni recommended that, to ensure the Bill does not

unduly infringe on freedom of speech, the exemption in subsection 150.1(7)

should not be qualified by adjectives. He proposed it read ‘This section does

not apply to conduct engaged in for satirical, academic or artistic purposes’.[58]

Figure 2: screenshot from Centrelink Fail - Honest Government Advert video (The Juice

Media)

Source: The Juice Media, ‘Centrelink

Fail – Honest Government Advert’, online video, Facebook, 9 January 2017.

Justification for new offences

A fundamental issue in relation to the Bill is whether the proposed

criminal offences are the most appropriate regulatory approach. The Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill suggests that there is currently a gap in the criminal

law and the new offences will ‘put the criminalisation of such conduct beyond

doubt’. It states:

It is essential that the public can trust in the legitimacy

and accuracy of statements made by Commonwealth bodies. The amendments are

critical to ensure the public has confidence in the legitimacy of

communications emanating from Commonwealth bodies, thereby safeguarding the

proper functioning of Government.[59]

However, beyond this point of principle, there is a lack of

clarity concerning the immediate need for the new offences or why other

regulatory approaches could not have been pursued. The Attorney-General’s

Department’s A

Guide to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement

Powers recommends those proposing new criminal

offences consider a range of legislative options for imposing liability for

contravening a statutory requirement.[60] This issue was raised by Australian Lawyers for Human

Rights which submitted:

the Minister should provide some clear examples of why such a

Bill is necessary and what particular mischief it aims to confront because

neither the Explanatory Memorandum nor the Second Reading Speech provide any

such important information for such profound impositions on the freedom of speech.[61]

The Australian Government has shown that through its

copyright ownership over logos and branding (such as the Medicare logo) that it

can potentially take legal action to prevent inappropriate use, reproduction

and distribution.[62]

Notably, the Human

Services (Medicare) Act 1973 (Cth) already prohibits commercial

uses of the name ‘medicare’ or ‘Medicare Australia’ without appropriate

authorisation.[63]

This offence is punishable by a fine not exceeding 20 penalty units ($4,200),

or 40 penalty units ($8,400) in the case of a body corporate.[64]

Concerns regarding persons and organisations impersonating a

Commonwealth body have arisen in the context of recent election campaigns. The Commonwealth

Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) includes a number of offences in relation to

the conduct of persons during elections. In particular, the Commonwealth

Electoral Act provides an offence for printing, publishing or distributing

‘any matter or thing that is likely to mislead or deceive an elector in

relation to the casting of a vote’. A person convicted may face imprisonment

for six months or a fine not exceeding 10 penalty units ($2,100), or both. A

body corporate could face a fine not exceeding 50 penalty units ($10,500).[65]

Within the Commonwealth Electoral Act larger penalties (up to two years

imprisonment) are reserved for offences such as bribery.[66]

While it is not articulated in the Explanatory Memorandum, impersonating

a Commonwealth body is also a component of some instances of criminal fraud or

‘scams’. As noted above, the Legal Services Commission of South Australia

supported the Bill because of its experiences with ‘the harm caused by scams

where callers claim to represent Commonwealth Government departments’.[67]

The problem of scams, which often rely on persons being

deceived by communications which appear to be from a trusted source (such as a

Commonwealth body), has led the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

(ACCC) to establish a dedicated website ScamWatch

to increase consumer awareness and track reports of scams. In 2016, the ACCC

noted that there were ‘a variety of threat-based scams which impersonated

government agencies’ with the most commonly impersonated agencies including the

Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Australian Taxation Office

(ATO), DHS, Centrelink and the AFP.[68]

In particular, ‘ATO scams’ accounted for the majority of threats based scams

reported to the ACCC in 2016 with over 20,000 reported and nearly $1.5 million

reported as lost by victims.[69]

Injunctions

Subdivision B of proposed Division 150 of the Criminal

Code contains proposed section 150.5, which provides that the

offence created in section 150.1 is enforceable under Part 7 of the Regulatory

Powers Act. This creates a legal framework for the use of injunctions to

enforce provisions.

The injunctions provision in the Bill appears to be the

first time an injunctions power in relation to an offence has been included in

the Criminal Code. This is reflected in item 3 of Schedule 1

which amends the Dictionary in the Criminal Code to insert a definition

of the Regulatory Powers Act.

Under proposed subsection 150.5(2) ‘any person

whose interests have been, or would be, affected by conduct’ in either of the

offences is an ‘authorised person’. An authorised person will be able to apply

for an injunction from any of the courts listed in proposed subsection

150.5(3).[70]

It is not apparent in the Explanatory Memorandum why the

Bill would provide that any affected person could apply for an injunction

rather than limiting it to the Commonwealth entities being misrepresented. The

broad definition of an ‘authorised person’ for the purposes of seeking

injunctions could lead to unintended consequences. References to, and use of,

the names and logos of Commonwealth Government entities are a common component

of Australian public discourse (see for example – Figure 3 below). The

injunctions provision may create perverse incentives for ‘affected’ persons to

seek injunctions with secondary purposes.

Figure 3:

extract of The NBN tagline, translated (The Gruen Team)

Source: The Gruen Team (@GruenHQ), ‘The NBN’s tagline,

translated’, tweet, 13 September 2017, https://twitter.com/GruenHQ/status/907917947233955840.

Concluding

comments

The Bill will introduce two offences for persons who engage

in conduct which results, or is reasonably capable of resulting, in a

representation that the person is, or is acting on behalf of, a Commonwealth

body. The scope of the proposed offences appears broader than that of the

existing offences in the Criminal Code dealing with impersonating, or

falsely representing to be, a Commonwealth officer. In particular, the fault

element applying to most elements of the offences (recklessness) increases the scope

of conduct which may potentially be captured by the proposed offences.

Concerns have been expressed that the proposed offences

could negatively impact on freedom of expression. In particular, the definition

of ‘conduct’ may insufficiently safeguard conduct undertaken for satirical, academic

and artistic purposes. The proposed injunctions power may also be controversial

through permitting ‘any’ affected person to apply for an injunction to prohibit

or prevent conduct amounting to false representation of a Commonwealth body.

Members, Senators and Parliamentary staff can obtain

further information from the Parliamentary Library on (02) 6277 2500.

[1]. D

Muller, Electoral

and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017, Bills digest, 101, 2016–17,

Parliamentary Library, 2017, p. 3–5; P Coorey, ‘"Mediscare"

delivers poll boost for Labor’, The Australian Financial Review, 24 June 2016, p. 1.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. ‘Mediscare

text deceit denied’, Herald Sun, 5 July 2016, p. 7.

[4]. M

Turnbull, ‘Malcolm

Turnbull, Bill Shorten election night speeches in full’, Herald Sun,

3 July 2016.

[5]. M

Dunn, ‘Fake

texts police probe’, Herald Sun, 4 July 2016, p. 10. M Doran and U

Patel, ‘"Mediscare"

text message investigation dropped by Australian Federal Police’, ABC

News (online edition), 3 August 2016.

[6]. Section

148.1 of the Criminal Code.

[7]. H

Belot and K Lawson, ‘Fake

medicare cards and rates debate dominate final days of ACT election campaign’,

The Canberra Times (online edition), 13 October 2016.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Joint

Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, The 2016 Federal Election: interim

report on authorisation of voter communication,

9 December 2016, p. 5.

[10]. Ibid.,

p. 16.

[11]. Ibid.,

p. 17.

[12]. Ibid.,

p. 17.

[13]. The

JSCEM’s second

interim report (March 2017) and third

interim report (June 2017) for this inquiry have not addressed this issue

further.

[14]. S

Ciobo, ‘Second

reading speech: Electoral and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017’, House

of Representatives, Debates, 6 September 2017, p. 9415.

[15]. Parliament

of Australia, ‘Electoral

and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2017 homepage’, Australian Parliament

website.

[16]. M

Farr, ‘Activist

grandfather feels legal wrath for doing what politicians have been doing for

months’, news.com.au, 23 November 2016.

[17]. H

Aston, ‘Turnbull

government threatens to sue grandfather over “save Medicare” website’, The

Sydney Morning Herald, 23 November 2016.

[18]. T

Burke, ‘Questions

without notice – Intellectual Property’, House of Representatives, Debates,

23 November 2016, p. 4153.

[19]. P

Karp, ‘Government

backs down on threat to sue campaigner for use of Medicare logo’, The

Guardian, 15 December 2016.

[20]. ‘Lawyers

despatched over Medicare logo row’, The Age, 30 November 2016, p. 5.

[21]. Senate

Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, Criminal

Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 [Provisions],

The Senate, Canberra, November 2017, p. 8.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Australian

Greens, Dissenting report, Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation

Committee, Inquiry

into the provisions of the Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a

Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 [Provisions], The Senate, Canberra,

November 2017, p. 10.

[24]. Ibid.

[25]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 12, 2017, The Senate, Canberra, 18 October 2017, p. 17.

[26]. ‘Medicare

campaign ban a PM “dummy spit”’, SBS News, 16 February 2017.

[27]. Australian

Greens, Dissenting report, Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation

Committee, Inquiry

into the provisions of the Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a

Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 [Provisions], op. cit., p. 9.

[28]. Electronic

Frontiers Australia, Submission,

Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the Criminal

Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 [Provisions], 17

October 2017, p. 2.

[29]. Legal

Services Commission of South Australia, Submission,

Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the Criminal

Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017 [Provisions],

12 October 2017, p. 1.

[30]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body)

Bill 2017, p. 2.

[31]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at p. 3 of the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill.

[32]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Human

rights scrutiny report, 11, 17 October 2017, p. 60.

[33]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Human

rights scrutiny report, 8, 15 August 2017, p. 101.

[34]. Ibid.,

pp. 102–3.

[35]. Ibid.,

p. 103.

[36]. Explanatory

Memorandum, op. cit., p. 9.

[37]. Section

3.1 of the Criminal Code.

[38]. Subsection

5.6(1) of the Criminal Code provides that, if an offence does not

specify a fault element, intention is the fault element for a physical element

of an offence that is conduct. Subsection 5.2(1) of the Criminal Code provides

that a person has intention with respect to conduct if he or she means to

engage in that conduct.

[39]. Subsection

5.6(2) of the Criminal Code provides that, if an offence does not

specify a fault element, recklessness is the fault element for a physical

element of an offence that consists of a circumstance or result.

[40]. The

fault element of recklessness applies to this physical element by reason of

subsection 5.6(2) of the Criminal Code (summarised above).

[41]. Under

subsection 5.4(4) if recklessness is a fault element for a physical element of

an offence, proof of intention, knowledge or recklessness will satisfy that

fault element.

[42]. Explanatory

Memorandum, op. cit., p. 7.

[43]. ‘Obtaining’,

‘gain’ and ‘loss’ are defined at section 130.1 of the Criminal Code.

‘Obtaining’ includes obtaining for another person and inducing a third person

to do something that results in another person obtaining. The Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill provides that ‘the phrase “public duty or function”

should be interpreted according to its ordinary and natural meaning’ and ‘is

not intended to apply to so-called “civic duties” of private citizens, such as

voting’: Explanatory

Memorandum, op. cit., p. 8.

[44]. A

Commonwealth company as within the meaning of the Public Governance

and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth)—see subsection 89(1).

[45]. Explanatory

Memorandum, op. cit., p. 7.

[46]. Extended

geographic jurisdiction-Category C is set out in section 15.3 of the Criminal

Code. As the Explanatory Memorandum notes the offences will apply whether

or not the conduct or the result of the conduct constituting the alleged

offence occurs in Australia. A defence may be available if there is no

equivalent offence under the law of a foreign country where the conduct occurs.

The defence does not apply if the person charged is an Australian national.

[47]. J

Gans, Submission

to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the

Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017

[Provisions], 28 September 2017, pp. 2–3.

[48]. A

Latin legal term to describe the mental or fault element required for most

offences in order to establish criminal responsibility, Australian Law

Dictionary, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2011.

[49]. Australian

Lawyers for Human Rights, Submission

to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the

Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017

[Provisions], 12 October 2017, p. 2.

[50]. M

Keenan, ‘Second

Reading Speech: Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body)

Bill 2017’, House of Representatives, Debates, 13 September 2017, p.

10178.

[51]. Section

15A of the Acts Interpretation Act provides ‘[e]very Act shall be read

and construed subject to the Constitution, and so as not to exceed the legislative

power of the Commonwealth, to the intent that where any enactment thereof

would, but for this section, have been construed as being in excess of that

power, it shall nevertheless be a valid enactment to the extent to which it is

not in excess of that power’. The constitutional doctrine of implied freedom of

political communication is discussed further below.

[52]. Halsbury’s

Laws of Australia [online], ‘Freedom of Political Communication’,

Constitutional Law, Vol 90(VII)(7), [90-7200 - 90-7250]. A recent example was Brown

v Tasmania [2017]

HCA 43 where the High Court of Australia ruled that certain provisions of

the Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Act 2014 (Tas) were invalid

as they impermissibly burdened the implied freedom of political communication.

[53]. Electronic

Frontiers Australia, Submission,

op cit., p. 2.

[54]. For

example, in Monis v R (2013) 249 CLR 92; [2013]

HCA 4 the High Court divided evenly on the issue of whether section 471.12

of the Criminal Code (which created an offence to use postal services in

a way reasonable persons would regard as offensive) infringed the implied

freedom of political communication and was therefore invalid.

[55]. Gans,

Submission,

op. cit., p. 5.

[56]. F

Ruby, Submission

to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the

Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017

[Provisions], 13 October 2017, p. 1.

[57]. G

Nanni, Submission

to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the

Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017

[Provisions], 12 October 2017, p. 1.

[58]. Ibid.

[59]. Explanatory

Memorandum, op. cit., p. 2.

[60]. Attorney-General’s

Department, ‘A

guide to framing Commonwealth offences, infringement notices and enforcement powers’,

September 2011, pp. 12–13.

[61]. Australian

Lawyers for Human Rights, Submission,

op. cit., p. 7.

[62]. K

Bowrey and M Handler, ‘Medicare

logo case shows the urgent need to update Australia’s IP laws’, The Conversation,

30 November 2016.

[63]. Human Services

(Medicare) Act 1973, sections 41C and 41CA.

[64]. Section

4AA of the Crimes

Act 1914 provides that a penalty unit is currently equal to

$210.

[65]. Section

329 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

[66]. Section

326 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act.

[67]. Legal

Services Commission of South Australia, Submission

to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the

Criminal Code Amendment (Impersonating a Commonwealth Body) Bill 2017

[Provisions], op. cit., p. 1.

[68]. Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), Targeting

scams: report of the ACCC on scams activity 2016, May 2017, p. 17.

[69]. Ibid.

[70]. Section

119 of the Regulatory Powers Act. The relevant courts are the Federal

Court of Australia, the Federal Circuit Court of Australia, the Supreme Court

of a State or Territory and the District Court (or equivalent) of a State or

Territory.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth

Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party,

this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and

communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as

long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence

terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this

publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of

publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists

in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may

be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and

any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament.

They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available

in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do

not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor

do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the

relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments

or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official

status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be

directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are

available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members

and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or

the Library’s Central Enquiry Point for referral.