Bills Digest No. 115,

2016–17

PDF version [708KB]

Jaan Murphy and Andrew Cameron

Law and Bills Digest Section

19

June 2017

Contents

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Repeal of

the four-yearly reviews of modern awards by the FWC

Current law

2012 review of the Fair Work Act

Changes proposed by the Productivity

Commission

What is an enterprise agreement?

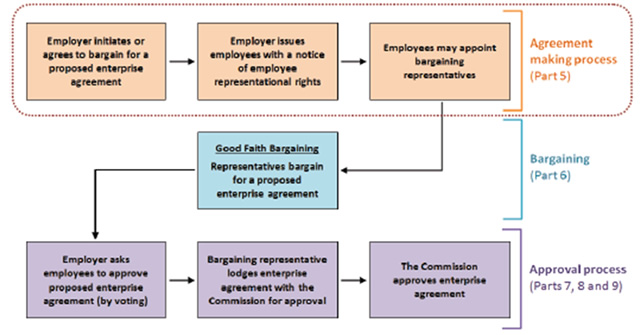

How is an enterprise agreement made?

Figure 1: making an enterprise

agreement

Factors considered by the FWC when

approving an enterprise agreement

Handing alleged misconduct or

incapacity of FWC Members

Committee consideration

Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee

Additional comments by Opposition

Senators

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions—Schedule 1

Issues with the four-yearly review

model

Proposed replacement model

Model proposed by the Bill

Repeal of requirement to conduct

four-yearly reviews

Alterations to modern award powers of

the FWC

Powers of the Full Bench and single

members of the FWC to vary or revoke modern awards

Only Full Bench can revoke a modern

award

Variation of modern awards by a

single Member of the FWC

Key issues and provisions—Schedule 2

Key issues and provisions—Schedule 3

Background to incapacity and

misbehaviour of judicial officers and equivalent offices

Current process for terminating or

suspending a Member of the FWC

Gaps in current system for

terminating or suspending certain Members of the FWC

Amendments related to complaints

against FWC Members

Extending the JMIPC Act to FWC

Members

Key issues and provisions—Schedule 4

Incomplete 4-yearly reviews of modern

awards

Approving enterprise agreements

Retrospective extension of the JMIPC

Act to FWC Members

Date introduced: 1

March 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Employment

Commencement: Schedule

1 will commence on 1 January 2018. Schedules 2, 3 and 4 will commence the

day after the Bill receives Royal Assent.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at June 2017.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4

Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend the

Fair Work

Act 2009 (the FW Act) and the Fair Work

(Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Act 2009 (the

FW Transitional Act) to:

- repeal

the requirement for the Fair Work Commission (FWC) to conduct four-yearly

reviews of modern awards from the beginning of 1 January 2018

- allow

the FWC to overlook ‘minor procedural or technical errors’ when approving an

enterprise agreement, where those errors were not likely to have disadvantaged

employees, including errors related to the Notice of Employee Representational

Rights (NERR) requirements

- ensure

that the existing complaint-handling powers of the Minister for Employment and

the President of the FWC apply to FWC Members who formerly held office in the

Australian Industrial Relations Commission (AIRC) and

- apply,

in a modified form, the Judicial

Misbehaviour and Incapacity (Parliamentary Commissions) Act 2012 (the

JMIPC Act) to FWC Members.[1]

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill’s measures are contained in four Schedules:

- Schedule

1 deals with the repeal of the four yearly reviews of modern awards by the FWC

- Schedule

2 deals the factors considered by the FWC when approving an enterprise

agreement

- Schedule

3 deals with the modified application of the JMIPC Act to FWC Members

and application of the FW Act to FWC Members who formerly held

office in the AIRC and

- Schedule

4 provides for application and transitional provisions in relation to the

amendments made by Schedules 1 to 3 of the Bill.

Background

As the Bill deals with three broad areas of reform, the

background to each is provided separately below.

Repeal of

the four-yearly reviews of modern awards by the FWC

Current law

Currently section 156 of the FW Act requires the

FWC to review all modern awards every four years. The reviews may result in the

FWC making new modern awards, or varying or revoking (cancelling) modern

awards.[2]

When reviewing or varying a modern award, section 134 of

the FW Act provides that the FWC must take into account the modern award

‘objective’. Relevantly, this includes ‘relative living standards’, the need to

provide additional remuneration for employees working on weekends and public

holidays, and the likely impact on productivity and employment costs.[3]

In relation to a four-yearly review of a modern award, the

FWC may only make a determination to vary a modern award’s minimum wage where

it is satisfied that the variation is justified by ‘work value’ reasons—that is

reasons related to the nature of the work, the skill and responsibility

attached to it and the conditions under which it is performed.[4]

Given the large number of modern awards, four-yearly

reviews of modern awards are often complex, protracted and controversial

processes involving large numbers of participants and submissions for various

interest groups, including employee organisations, industry groups and

employers.

2012 review

of the Fair Work Act

In relation to the four-yearly review of modern awards,

the Labor Government’s 2012 Fair Work Act Review noted:

On recommendations for amendment to the provisions relating

to award variations, the Panel notes the Government’s policy intention of

establishing a stable safety net, including by only providing for

four-yearly reviews and otherwise limited capacity for variation. Given

that the first four-yearly review of modern awards is still some time away and [Fair

Work Australia] FWA’s interim award review has yet to be finalised, the

Panel is unable to justify making recommendations that would upset arrangements

for general reviews of modern awards.[5]

(emphasis added)

In relation to ‘calls for increased ability to seek

variations outside of general reviews’ the Expert Panel stated ‘such a move

would be counter to the policy of maintaining a stable safety net’ and would be

‘likely to result in increased speculative claims to deal with short-term

concerns of both employers and employees’ and therefore did not recommend any amendments

in that area.[6]

Changes

proposed by the Productivity Commission

The Productivity Commission’s Report on Australia’s Workplace

Relations Framework (the PC Report) examined the role of modern awards

within Australia’s workplace relations framework. The Productivity Commission

noted that:

... awards are an Australian idiosyncrasy with some undesirable

inconsistencies and rigidities, but they are an important safety net and a

useful benchmark for many employers.[7]

The Productivity Commission recommended that the FW Act

be amended to:

- remove

the requirement for continued four yearly reviews of modern awards

(recommendation 8.1)

- add

the requirement that the wage regulator review and vary awards as necessary to

achieve the revised modern awards objective specified in recommendation 8.3,

namely that modern awards, together with the National Employment Standards,

provide a minimum safety net of terms and conditions, which promote the overall

wellbeing of the community, taking into account:

- the

needs of the employed

- the

need to increase employment

- the

needs of employers

- the

needs of consumers and

- the

need to ensure modern awards are easy to understand.[8]

The Government argues the Bill ensures that the framework

for the making, varying and revoking of modern awards outside of the four-yearly

reviews will continue to provide ‘a balanced, fair and sensible safety net of

terms and conditions of employment’.[9]

As the FW Act already provides that the FWC ‘must ensure that modern

awards, together with the National Employment Standards, provide a fair and

relevant minimum safety net of terms and conditions’.[10]

Schedule 1 of the Bill gives partial effect to the Productivity

Commission’s recommendation 8.1, because the Bill does not replace the current

modern awards objective in section 134 of the FW Act with the recommended

revised modern awards objective specified in recommendation 8.3 (as set out

above).

What is an

enterprise agreement?

An enterprise agreement is a collective agreement dealing

with certain permitted matter (such as wages) made between employees and an

employer made at the enterprise level. They are enforceable under the FW Act,

and set out terms and conditions of employment, as well as the rights and

obligations of the employees and the employer covered by the agreement.[11]

An enterprise agreement must meet a number of requirements

under the FW Act before it can be approved by the FWC.

How is an

enterprise agreement made?

The process for making enterprise agreements is set out in

Part 2-4 of the FW Act. The diagram below sets out this process in

simplified form.

Figure 1: making an enterprise agreement

Source: Fair Work Commission,

Benchbook:

enterprise agreements, Fair Work Commission website, 3 April

2017, p. 68.

Importantly, an enterprise agreement does not operate, and

has no legal force, until it is approved by the FWC.[12]

Factors

considered by the FWC when approving an enterprise agreement

Section 188 of the FW Act deals with when an

enterprise agreement (EA) has been genuinely agreed to, a prerequisite

for any EA being approved by the FWC.[13]

As noted in the figure above, one important step in the

process of making an enterprise agreement is the employer issuing a Notice of

Employee Representational Rights (NERR) within 14 days of the commencement of

bargaining.[14]

As the name suggests, a NERR notifies each employee of his or her bargaining

rights.[15]

The content of the NERR is prescribed by regulation.[16]

NERRs are intended to inform employees of their right to appoint a bargaining

representative to negotiate on their behalf during the making of an enterprise

agreement, and where an employee is a union member, to advise them that the

union will be their bargaining representative by default (unless the employee

appoints another representative).[17]

Importantly, the FWC and courts have strictly interpreted

certain procedural requirements imposed by the FW Act, especially in

regards to the issuing of a NERR.[18]

This had led to criticism that ‘form’ unduly dominates over the substance of

key steps in negotiating and ultimately, approving an EA.[19]

For example, the Productivity Commission noted one infamous case where an

employer:

... provided three pages — stapled together — to all of the

employees to be covered by a proposed enterprise agreement. Some bargaining

ensued, an agreement was struck and the agreement was lodged with the FWC.

However, by attaching the three documents together, the employer contravened

requirements about the form of notice to be given to employees. The FWC had no

real discretion in the matter, and was obliged by the Fair Work Act to

reject the agreement. So, absurdly, the employer had to recommence the

agreement process. There is a convincing variety of similar examples.[20]

As a result, the Productivity Commission recommended that

the FW Act be amended to:

- allow

the FWC wider discretion to overlook minor procedural or technical errors when

approving an agreement, as long as it is satisfied that the employees were not

likely to have been placed at a disadvantage because of an unmet procedural

requirement and

- extend

the scope of this discretion to include minor errors or defects relating to the

issuing or content of a notice of employee representational rights.[21]

Schedule 2 of the Bill gives effect to this recommendation.

Handing

alleged misconduct or incapacity of FWC Members

On 19 October 2015, Peter Heerey was appointed to inquire

into and report on complaints about FWC Vice President Michael Lawler.[22]

The review was to inquiry into and report on complaints about

Vice President Lawler, and related issues, including:

- the

processes of the FWC to investigate complaints and allegations made against

members of the FWC, including those appointed under previous workplace

relations legislation

- the

appropriateness of any process in the FWC to manage conflicts of interest and

- whether

there was a reasonable basis for both Houses of Parliament to consider

requesting the Governor-General to remove Vice President Lawler from the FWC on

the grounds of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.[23]

Relevantly to this Bill, the Inquiry report (the Heerey

Report) found:

- the

complaint investigation processes of the FWC are adequate, and are consistent

with those recently provided by statute for other comparable federal judicial

and quasi-judicial bodies and

- the

current arrangements in the FWC for managing conflicts of interest are

appropriate.[24]

However, Mr Heerey recommended that the provisions of the JMIPC

Act ‘should be extended to apply to termination proceedings against persons

who are not judges but hold office subject only to termination by the

Governor-General on addresses of both Houses of Parliament’.[25]

This recommendation was not made in response to identified deficiencies with

the current processes of the FW Act, but to create consistency between Chapter

III judges under the Australian Constitution and FWC Members in response

to the policy developments that had applied to the former since the

introduction of the JMIPC Act in 2012.

The amendments proposed by the Bill give effect to that

recommendation, but also deal with the issues identified by Mr Heerey regarding

sections 581A and 641A (and related provisions) of the FW Act.

Section 581A empowers the President of the FWC to deal

with a complaint about the performance of another FWC Member, and ultimately

allows for each House of the Parliament to consider whether to present to the

Governor-General an address praying for the termination of the appointment of

the FWC Member. Section 641A provides the same power to the Minister. Mr Heerey

identified that sections 581A and 641A probably did not apply to FWC Members

who were appointed to the AIRC pursuant to the Workplace Relations Act 1996

(like Vice President Lawler), although they were subject to preserved

provisions that essentially provided both the President and the Minister (when

read together with sections 61 and 64 of the Constitution)

with the same powers.[26]

As of 2 December 2016 there were 12 serving FWC Members who were appointed

under the Workplace Relations Act.[27]

Mr Heerey recommended:

... because of the uncertainty surrounding the applicability of

sections 581A and 641A to former AIRC Members, there would be some utility in

amending the present legislation to ensure (so far as is constitutionally

possible) that these provisions apply to all Members of the FWC, irrespective

of when they were appointed.[28]

The Bill gives effect to that recommendation.

Committee

consideration

Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee

The Bill was referred to the Senate Education and

Employment Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 22 May 2017. Further

details of the inquiry and the Committee’s report are available on the inquiry

homepage.

The Committee received 14 submissions, primarily from industry

bodies and unions.[29]

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry made concise submissions

outlining its support for the Bill, while the Australian Council of Trade

Unions (ACTU) supported only the provisions in Schedule 3 of the Bill, which relate

to the investigation of alleged misconduct by FWC Members. The ACTU’s

opposition to the repeal of the four yearly reviews was based on concerns

regarding the transitional provisions, as well as opposition to the default

requirement for variations to modern awards to be made by the Full Bench of the

FWC only. However, the ACTU supports the repeal of the four yearly reviews in

principle.[30]

The FWC also made submissions to the Committee and

primarily addressed the proposed discretion to be granted to the FWC to approve

enterprise agreements where there have been minor procedural or technical

errors in complying with procedural requirements of the FW Act. The FWC

identified that Schedule 2 would not apply retrospectively to applications made

before its commencement. The FWC proposed that significant delay, inconvenience

and expense could be avoided if the Bill were amended to apply the Schedule 2

items retrospectively to applications made prior to its commencement.[31]

The Queensland Law Society (QLS) made brief submissions in

relation to proposed section 641B identifying several concerns with the

approach taken by the Bill in modifying the JMIPC Act to apply to FWC

Members. It recommended that instead a separate Bill be introduced to amend the

JMIPC Act to extend its application to quasi-judicial officers.[32]

On 22 May 2017 the Committee published its report on the

Bill.[33]

The Committee recommended that the Bill be passed, subject to amendments to the

Bill to ‘provide for the new approval discretion to apply to applications made

prior to the commencement of Schedule 2’.[34]

This is a reference to proposed item 2 of Schedule 2 of the Bill that expands

the definition of ‘genuinely agreed’ under the FW Act to include cases

where there have been ‘minor procedural or technical errors’ in complying with

the FW Act’s procedural requirements for the approval of enterprise

agreements. The amendment recommended by the Committee was sought by the Fair

Work Commission in its submission to the Committee.[35]

Additional

comments by Opposition Senators

Whilst ‘expressing in-principle support for improvements to

the enterprise bargaining process’ proposed by the Bill, the Opposition

Senators raised three concerns about the Bill.

First, it was argued that whilst the purpose of item

26(1) of Schedule 4 of the Bill (a transitional provision) is to allow

incomplete four yearly reviews ‘to be completed if they are still on foot at

the time the abolition comes into effect’, the provision appears only to apply

to the ‘award stage’ of such reviews and not the ‘common issues’ stage.[36]

Second, the Opposition Senators noted:

... the requirement for a Full Bench of the Fair Work

Commission to be constituted to make, vary or revoke a modern award is

unnecessarily cumbersome. Given the government's enthusiasm for reducing the

burden on resources of the FWC and bargaining parties, this provision should be

amended so that only a single member is required.[37]

Third, the Opposition Senators noted that the use of the

term ‘disadvantaged’ in the provision allowing the FWC to disregard minor

technical or procedural issues when approving enterprise agreements does not

reflect the ‘intent of the procedural requirements, which is to ensure the

enterprise agreement is genuinely agreed to’.[38]

As a result, the Opposition Senators recommended that the

Senate amend the Bill to address the three issues discussed above.[39]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of

Bills considered the Bill and noted that the JMIPC Act establishes a

framework for the conduct of investigations by a Parliamentary Commission, with

powers to hold hearings and take evidence on oath, require the production of

documents and issue search warrants.[40]

It noted that proposed section 641B, at item 1

of Schedule 3 to the Bill, would apply the JMIPC Act to FWC

Members in a modified form to allow a Parliamentary Commission to be

established by the Houses of Parliament to investigate and report on alleged

misbehaviour or incapacity of a FWC Member. The application of the JMIPC Act

to FWC Members follows Peter Heerey’s recommendation in the Heerey Report for

the provisions of the JMIPC Act to ‘be extended to apply to termination

proceedings against persons who are not judges but hold office subject only to

termination by the Governor-General on addresses of both Houses of Parliament’.[41]

Practically, section 641B introduces a third mechanism for the investigation

and handling of alleged misbehaviour or incapacity of FWC Members (the other

mechanisms being the FWC President’s powers under section 581A and the

Minister’s powers under section 641A).

The Committee noted that it had raised a number of concerns

in relation to the Judicial

Misbehaviour and Incapacity (Parliamentary Commissions) Bill 2012 (JMIPC

Bill) when it was before the Parliament.[42]

The Committee noted that as the Bill ‘seeks to expand the ambit of the JMIPC

Act to include FWC Members’, the Committee referred to its previous

comments about the JMIPC Bill in relation to:

- the

power of a Commission to issue search warrants

- balancing

privacy and reputational interests of persons subject to investigation by a

Parliamentary Commission

- the

reversal of the evidential burden of proof where a person wishes to use a

'reasonable excuse' defence to offences relating to failure of a witness to

appear or failure of a witness to produce a document or thing and

- the

abrogation of the privilege against self-incrimination.[43]

The Committee concluded that whilst the provisions in

Schedule 3 ‘may be considered to trespass unduly on personal rights and

liberties’, it left consideration of ‘the appropriateness of expanding the

ambit of the JMIPC Act to include FWC Members’ to the Senate as a

whole.[44]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

The Opposition appears to support the Bill in general

terms, but recommended three amendments to the Bill.[45]

As the Greens Senators on the Senate Education and Employment Legislation

Committee inquiry into the Bill did not issue a dissenting report or make

additional comments, it would appear that the Greens support the Bill, subject

to the recommendations made by the Committee.

At the time of writing, the policy position of other non-government

Members and Senators was not known.

Position of

major interest groups

The Government advises that in November 2016 the

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), the Australian Industry

Group (AIG) and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) jointly wrote to

the Minister for Employment, asking the government to abolish the four-yearly reviews

of modern awards.[46]

The Government states that this suggests ‘there is broad support for reforms to

repeal four-yearly reviews’.[47]

In their submissions to the Senate Education and

Employment Legislation Committee inquiry into the Bill, the ACCI and AIG both expressed

general support for the Bill, although the ACCI suggested various technical

amendments.[48]

The ACTU expressed support for Schedules 1 and 3 of the Bill (whilst suggesting

various technical amendments) but opposed Schedule 2 of the Bill on the basis

that ‘the provisions run counter to the objective that bargaining is inclusive,

fair and well informed’.[49]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum advises that the financial

impact of the Bill to government is nil.[50]

However, the Government has stated:

Employee groups, employer groups and the Fair Work Commission

spend an enormous amount of time and money in undertaking these reviews. Their

abolition will save employers and unions about $87 million over the next 10 years.

This amount represents a significant regulatory burden.[51]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the

Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared

in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[52]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considers

that the Bill does not raise human rights concerns.[53]

Key issues

and provisions—Schedule 1

As noted above, currently Division 4 of Part 2-3 of the FW

Act requires the FWC to review all modern awards every four years, and provides

that the FWC can only vary modern award minimum wages for ‘work value’ reasons.

Issues with

the four-yearly review model

The Productivity Commission noted that in practice the ‘current

four yearly review appears to be an expensive exercise requiring extensive

investment from interested parties’[54]

due in part to the fact that ‘the FWC is required to review every clause in every

award’.[55]

Further, the Productivity Commission noted:

... due to the breadth of the issues before the FWC, the

current review is likely to take at least two years to be completed. After

this, the system should remain relatively ‘stable’ for two years before the

next review is due to commence.[56]

Proposed

replacement model

The Productivity Commission recommended that instead of four-yearly

reviews of modern awards, the FW Act should be amended to use a more

targeted approach to reviewing awards, with efforts focused on aspects of

awards that are the source of greatest problems.[57]

In essence the Productivity Commission suggested that the four-yearly award

reviews be replaced with a process for reviewing modern awards that can be

initiated by affected parties or by the FWC itself.

Model

proposed by the Bill

Because of the substantial demands placed on parties by

the system of four-yearly reviews, the Government argues that the current four-yearly

award review process ‘does not meet the Act’s objective to create a simple,

easy to understand, sustainable award system’.[58]

Accordingly, the Bill would remove the four-yearly reviews of modern awards and

amend the FW Act to allow affected parties to apply to vary a modern

award on a case by case basis. This will allow the FWC to not only focus

efforts on aspects of awards that are the source of the greatest problems (as

identified by the parties bringing such applications), but it will also allow

the FWC to conduct its own reviews where it considers it appropriate to do so.

Repeal of

requirement to conduct four-yearly reviews

Item 8 of Schedule 1 of the Bill will repeal

Division 4 of Part 2-3 of the FW Act and therefore remove the

requirement for the FWC to conduct four-yearly reviews of modern awards. Items

1–7 of Schedule 1 of the Bill make consequential amendments to reflect the

repeal of the requirement to conduct four-yearly reviews.

Alterations

to modern award powers of the FWC

Division 5 of Part 2-3 of the FW Act deals with how

the FWC can exercise its powers in relation to modern awards outside of the four-yearly

review process. Currently section 157 of the FW Act allows only a Full

Bench of the FWC to make modern awards outside of the four-yearly review

process (a single Member can vary awards outside of the four-yearly review

process).

Proposed subsection 157(2A) inserts an identical

definition of ‘work value reasons’ to that used in current subsection 156(4)

(which will be repealed by item 8). Read with existing subsection 157(2)

(as amended by item 12 of Schedule 1 to the Bill), this amendment

will ensure that variations to the minimum wages paid under modern awards can

only occur for ‘work value’ reasons, namely ‘reasons justifying the amount that

employees should be paid for doing a particular kind of work’ related to:

- the

nature of the work

- the

level of skill or responsibility involved in doing the work or

- the

conditions under which the work is done.[59]

Powers of

the Full Bench and single members of the FWC to vary or revoke modern awards

As noted above, currently only a Full Bench of the FWC is

able to make a modern award. In contrast, a single member of the FWC may vary

or revoke a modern award outside of the four-yearly review process.[60]

Only Full

Bench can revoke a modern award

Proposed subsection 616(3B), at item 18 of

Schedule 1, provides a default rule that any determination to revoke a modern

award must be made by a Full Bench. This is a change from the existing

framework under which a single FWC Member could revoke a modern award.[61]

Variation

of modern awards by a single Member of the FWC

Proposed paragraphs 582(4)(ab) and (e), at items

15 and 16 of Schedule 1, along with proposed subsections 616(3C)

and (3D) at item 18 of Schedule 1, will allow the President of

the FWC to direct a single FWC Member to conduct a variation matter for a

modern award in various circumstances, as discussed below.

Proposed subsection 616(3C) provides that by default,

a determination to vary a modern award must be made by a Full Bench. This is a

change from the existing framework, under which a single FWC Member can vary a

modern award outside of the four-yearly review process. The Government argues:

In the absence of the 4 yearly review mechanism, where

reviews were conducted by a Full Bench, it is appropriate for a Full Bench to

consider such matters before making any determinations to vary modern awards.[62]

However, proposed subsection 616(3D) will allow the

President of the FWC to direct a single FWC Member to conduct a variation

matter for a modern award when it relates to the exercise of a power under:

- section

159 (variation to update or omit name of employer, organisation or outworker

entity)

- section

160 (variation to remove ambiguity, uncertainty or correct error) or

- section

161 (variation on referral by Australian Human Rights Commission).

The Government notes that the above reflects that ‘some

modern award variations may relate to routine matters’, and hence ‘it would be

appropriate for a single FWC Member to perform that function’.[63]

Proposed paragraph 616(3D)(b) will also allow the

President to direct a single FWC Member to conduct a variation under section

157 where the President considers it appropriate to do so in relation to:

- a

single award or

- two

or more awards relating to the same industry or occupation.

The Government notes that an example of when proposed

paragraph 616(3D)(b) might be used is when an application is ‘made with the

support of all stakeholders to repeal redundant references from a single modern

award’ but also notes:

Where applications to vary modern awards may relate to more

significant or contentious matters, or may potentially present a ‘test case’

that could emerge as a common issue across awards, the default position for

Full Bench consideration will prevail.[64]

The Government also notes that appeal and review rights to

the Full Bench from single Member decisions to vary a modern award will

continue to be available.[65]

Items 10, 12, 14, and 17 are consequential

amendments reflecting the above proposed changes.

Key issues

and provisions—Schedule 2

Section 188 of the FW Act sets out a list of

matters for the FWC to consider when determining whether an EA has been

genuinely agreed to by the employees covered by the agreement. An EA must have

been genuinely agreed to before the FWC can approve it.[66]

As noted above, the FWC and courts have strictly

interpreted certain procedural requirements imposed by the FW Act,

especially in regards to the issuing of a NERR, that must be considered under

section 188.[67]

This had led to criticism that ‘form’ unduly dominates over the substance of

key steps in negotiating and ultimately, approving an EA.[68]

Proposed subsection 188(2), at item 2 of

Schedule 2, provides that an enterprise agreement will also have been genuinely

agreed to if the FWC is satisfied that the agreement would have been genuinely

agreed to but for any minor procedural or technical errors made in relation to:

- the

requirements referred to in paragraph 188(1)(a) or (b), namely:

- the

access period during which employees are provided with a copy of the proposed

agreement for consideration before voting

- notification

of the time, place and method of the vote for the proposed EA and

- ensuring

that the terms of the proposed EA and the effect of those terms are explained

to relevant employees in an appropriate manner (taking into account the

particular circumstances and needs of the relevant employees)

- the

requirement that employees are not requested to approve the proposed EA until

21 days after the last NERR was given

- the

agreement was made in accordance to relevant procedures for the type of

agreement (single or multi‑enterprise non-greenfields agreement) or

- the

requirements related to the NERR under sections 173 and 174.

However, even where the FWC is satisfied that the

agreement would have been genuinely agreed to but for any of the minor

procedural or technical errors noted above, proposed paragraph 188(2)(b)

provides that the FWC must also be satisfied that the employees covered

by the proposed EA ‘were not likely to have been disadvantaged by those

errors’.

The effect of proposed subsection 188(2) is that an

enterprise agreement will have been genuinely agreed to (and therefore able to

be approved by the FWC) despite any minor procedural or technical error if the

employees were not likely to have been disadvantaged by those errors. This will

prevent the types of cases identified by the Productivity Commission as being

‘absurd’ from occurring in the future.[69]

Key issues

and provisions—Schedule 3

Schedule 3 responds to issues identified in how incapacity

and misbehaviour of FWC Members is dealt with under the FW Act

identified by Peter Heerey in the Heerey Report.[70]

Background

to incapacity and misbehaviour of judicial officers and equivalent offices

Currently sections 641 and 642 of the FW Act allow

for the termination (section 641) and suspension (section 642) of Members

of the FWC by the Governor-General on the grounds of ‘proved misbehaviour’ or

being ‘unable to perform the duties of his or her office because of physical or

mental incapacity’. As such, they reflect the wording of section 72 of the Constitution

(which deals with, amongst other things, the removal of judicial officers).

Current

process for terminating or suspending a Member of the FWC

Section 581 of the FW Act provides that the

President is responsible for ensuring that the FWC performs its functions and

exercises its powers in a manner that is efficient and adequately serves the

needs of employers and employees throughout Australia.

In turn, section 581A empowers the President to deal with

complaints about the performance of another FWC Member, and to take any

measures that the President believes are reasonably necessary to maintain

public confidence in the FWC, including (but not limited to) temporarily

restricting the duties of the FWC Member. Importantly, a complaint will only

trigger section 581A if it about the performance by a FWC Member of his

or her duties (performance being decisions or conduct in relation to cases,

although it can also extend to non‑performance of duties).[71]

The President must refer a complaint about a FWC Member to

the Minister if they are satisfied:

- one

or more of the circumstances that gave rise to the complaint have been

substantiated and

- each

House of the Parliament should consider whether to present to the

Governor-General an address praying for the termination of the appointment of

the FWC Member.[72]

Subsection 581A(5) provides that the Minister must then

‘consider whether each House of the Parliament should consider the matter’,

with section 641A providing the necessary powers to the Minister to ‘handle’

the complaint for the purpose of:

- considering

whether the Houses of Parliament should consider whether to present to the

Governor-General an address praying for the termination of the appointment of

the FWC Member and

- considering

whether to advise the Governor-General to suspend the FWC Member.[73]

Section 641 then provides that the Governor-General may

terminate the appointment of an FWC Member if an address praying for the

termination is presented by each House of the Parliament on one the following

grounds:

- proved

misbehaviour or

- the

Member being unable to perform the duties of his or her office because of

physical or mental incapacity.

Section 642 allows the Governor-General to suspend the

appointment of an FWC Member (other than the President) on the advice of the

Minister.[74]

Suspension can only occur (subject to the process outlined below) on the basis

of one the following grounds:

- misbehaviour

or

- the

Member being unable to perform the duties of his or her office because of

physical or mental incapacity.

As such, the process leading to the suspension or

termination of a FWC Member (other than the President) is as follows:

- the

Minister makes a recommendation to Governor-General to suspend a FWC Member

under paragraph 641A(b) or the FW Act

- the

Governor-General may suspend the FWC Member at this time, on the basis

of the advice provided

- if

the Governor-General does suspend the FWC Member, the Minister must, within seven

sitting days of suspension, table a statement identifying the Member and setting

out grounds for suspension in each House of Parliament

- if

both Houses resolve that the appointment of the FWC Member should be terminated,

then the Governor-General must terminate the appointment of the FWC

Member and

- if

one of the Houses of Parliament does not pass a resolution to terminate within

15 sittings days, the suspension of the FWC member ends.[75]

This means that both the House of Representatives and the

Senate must agree in order for the appointment of a FWC Member to be

terminated. If one House disagrees or fails to pass the resolution calling for

the termination of the FWC Member, subsection 642(4) provides that the

suspension terminates.

Note that there is no requirement to suspend an FWC member

before termination. The Minister may decide to proceed directly to termination

under section 641 of the FW Act, the difference being that the

Governor-General does not have discretion to refuse the resolution of the Parliament

calling for the appointment of a suspended FWC member to be terminated.

Gaps in

current system for terminating or suspending certain Members of the FWC

The Heerey Report identified gaps in the current system

for terminating or suspending certain Members of the FWC, specifically Members

appointed to the AIRC under the Workplace Relations Act.[76]

Mr Heerey noted:

Section 581A of the Fair Work Act probably does not

apply to FWC Members like Vice President Lawler who had been appointed to the

AIRC under the Workplace Relations Act. While there is some doubt about

this matter, the better view is that s 581A cannot properly be viewed as a mere

supplementary or machinery provision which can sit together with the preserved

terms and conditions of former AIRC Members. As such, it would be unsafe for

the President to utilise powers under the section against a former AIRC Member unless

the Fair Work Act were amended to make the position clear.[77]

(emphasis added)

After examining the options for dealing with complaints

about FWC Members appointed under previous legislation, Mr Heerey concluded that

although FWC Members appointed under the Workplace Relations Act have

‘the rank and status of a Federal Court judge’ such persons are not ‘a Chapter

III judge’ and hence the JMIPC Act could not (in its current form) apply

to investigations involving them. Nonetheless:

... there would seem to be logic in extending the provisions of

the Judicial Misbehaviour and Incapacity Act to cover termination

proceedings against persons like Vice President Lawler who are not judges but

hold office on Act of Settlement terms. Further, because of the uncertainty

surrounding the applicability of sections 581A and 641A to former AIRC Members,

there would be some utility in amending the present legislation to ensure (so far

as is constitutionally possible) that these provisions apply to all Members of

the FWC, irrespective of when they were appointed.[78]

The amendments proposed in Schedule 3 of the Bill give

effect to the two issues identified above, namely:

- doubt

about the applicability of sections 581A, 641, 641A and 642 of the FW Act

to FWC Members appointed under the Workplace Relations Act and

- the

inapplicability of the JMIPC Act (in its current form) to investigations

of persons ‘who are not judges but hold office on Act of Settlement terms’,

including FWC Members.

Amendments related

to complaints against FWC Members

Item 2 of Schedule 3 to the Bill inserts proposed

clause 6A into Schedule 18 to the Fair Work

(Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Act 2009 (the FW

Transitional Act).

Proposed clause 6A will ensure that the powers of

the FWC President and the Minister under sections 581A and 641A of the Act

(described above) will apply in relation to complaints made about an FWC Member

who was appointed to the AIRC under the Workplace Relations Act 1996.

Currently sections 82 and 86 of the Workplace Relations

Act 1996 (preserved by clause 2 of Schedule 18 of the FW Transitional

Act in relation to AIRC Members who transferred to the FWC) provide for the

‘removal from office’ of such FWC Members on the grounds of proved misbehaviour

or incapacity.[79]

The Heerey Report raised doubts about the powers of Minister and

President in relation to Members of the FWC appointed to the AIRC under the Workplace

Relations Act, based on the apparent inability of the preserved terms under

the Workplace Relations Act to ‘sit together’ with the corresponding FW

Act provisions (namely, sections 581A and 641A).[80]

Proposed clause 6A of Schedule 18 of the FW

Transitional Act will apply sections 581A and 641A of the FW Act as

if they were amended to refer to preserved provisions of the Workplace

Relations Act that govern the removal from office of a Presidential Member

(section 82) or a Commissioner (section 86) who was an AIRC Member who

transferred to the FWC. This ensures that the terms and conditions of

appointment for and other arrangements pertaining to former AIRC Members

(including termination) are dealt with together under the new framework.[81]

Extending

the JMIPC Act to FWC Members

The JMIPC Act only applies to Chapter III judges.

It provides for the appointment of ad hoc commissions to investigate and report

to Parliament on the alleged misbehaviour or incapacity of a ‘Commonwealth

judicial officer’ so that Parliament may be ‘well informed to consider’ whether

to pray for removal of the officer under section 72(ii) of the Constitution.[82]

The JMIPC Act enables the Parliament to establish a

Commission of inquiry, comprised of members nominated by the Prime Minister and

appointed by both Houses of Parliament.[83]

Whilst Commissions appointed under the JMIPC Act are given various

coercive investigative powers,[84]

section 20 of the JMIPC Act contains detailed natural justice

provisions. However, as noted in the Explanatory Memorandum, a Commission

constituted under the JMIPC Act:

... does not determine whether facts are proved or make

recommendations to the Parliament about the removal of a judge. A Commission

only considers the threshold question of whether there is evidence of conduct

by a judicial officer that may be capable of being regarded as misbehaviour or

incapacity, and reports on these matters to the Parliament. It is for the

Houses of Parliament to determine whether they regard particular conduct as

proved misbehaviour or incapacity.[85]

(emphasis added)

As noted by Mr Heerey, the definition of ‘Commonwealth

judicial officer’ used in the JMIPC Act ‘in effect is confined to judges

appointed under Chapter III of the Constitution’.[86]

Mr Heerey noted that although the Workplace Relations Act provided

Members of the AIRC ‘the rank and status of a Federal Court judge’, such

persons are ‘not a Chapter III judge’ and the JMPIC Act cannot apply to

investigations of such persons.[87]

Nonetheless Mr Heerey formed the view that there was ‘some

logic’ in extending the JMIPC Act to cover persons ‘who are not judges

but hold office on Act of Settlement terms’.[88]

The proposed amendments would align the preparatory

procedures for removal under section 641 of the FW Act more closely

with those in the JMIPC Act.

Proposed section 641B of the FW Act, at item

1 of Schedule 3 to the Bill, would apply a modified version of the JMIPC

Act to FWC Members, regardless of when they were appointed to the FWC. Paragraphs

56 to 59 of the Explanatory Memorandum contain a detailed explanation of how

the JMIPC Act will be modified to apply to FWC Members. In summary,

however, the effect of proposed section 641B will be that the Parliament

can establish a Commission to investigate and report on alleged misbehaviour or

incapacity of an FWC Member, with a view to considering whether to request the

Governor-General to either:

- remove

a FWC Member appointed under the Workplace Relations Act or

- terminate

the appointment a FWC Member appointed under the FW Act.

The amendments are consistent with the recommendations of

the Heerey Report that the FW Act should adopt (in modified form)

the procedures under the JMIPC Act. Consequently, the interpretation of

terms and concepts in the FW Act that are (or are proposed to be) shared

with section 72(ii) of the Constitution and the JMIPC Act (such

as ‘proved misbehaviour’ and ‘incapacity’) can be informed by existing constitutional

jurisprudence and jurisprudence on the interpretation of the JMIPC Act. However,

this jurisprudence will only be of persuasive value only, since the

constitutional and JMIPC Act provisions are not of direct application.[89]

In its submission to the Senate Committee’s inquiry into

the Bill the Queensland Law Society (QLS) expressed concern with proposed

section 641B and the approach of applying modified provisions of the JMIPC

Act to FWC Members. The QLS stated that the approach:

- arguably makes the precise legal position difficult to identify as it

requires reference to two Acts in order to determine the law;

- means that when subordinate legislation is proposed, it will be

necessary for Parliamentary drafters to refer to both the JMIPC Act and

this legislation to ensure that any subordinate legislation is appropriate for

both Acts and considers all issues; and

- generally complicates the statute book.[90]

The QLS also stated that the approach appeared to increase

the risk of unintended consequences such as inconsistent interpretations of the

two pieces of legislation. Despite the criticism the QLS did not express

opposition to the reform generally, and suggested that a separate amendment to

the JMIPC Act to apply it to FWC Members would be appropriate to avoid

the problems it had identified.

Key issues

and provisions—Schedule 4

Schedule 4 provides for application and transitional

provisions in relation to the amendments made by Schedules 1 to 3 of the Bill.

Incomplete

4-yearly reviews of modern awards

Item 1 of Schedule 4 inserts proposed Part 5

into Schedule 1 of the FW Act, consisting of proposed clauses 25 to 29.

Proposed clause 26 provides that if the FWC has active four-yearly

review matters that have commenced but have not yet been concluded when Schedule

1 to the Bill commences (1 January 2018), current Division 4 of Part 2-3 of the

FW Act (which deals with four-yearly reviews) and necessary related provisions

will continue to apply in relation to those matters. This will ensure that

reviews that are on foot when the amendments commence are able to be completed.

Approving

enterprise agreements

Proposed clause 28 of Schedule 1 to the FW Act

provides that proposed subsection 188(2) (at item 2 of Schedule 2 to the

Bill), which avoids minor procedural or technical errors in EA processes

automatically resulting in the rejection of the EA, will apply to applications

for approval of an EA that are made to the FWC after the commencement of

Schedule 2 to the Bill. This means that minor errors occurring before

commencement that relate to an EA that is submitted for approval after

commencement can benefit from the more relaxed approach provided in the Bill.

Retrospective

extension of the JMIPC Act to FWC Members

Proposed clause 29 of Schedule 1 to the FW Act

provides that proposed section 641B (at item 1 of Schedule 3

to the Bill, which extends a modified version of the JMIPC Act to all

FWC Members) will apply in relation to alleged misbehaviour or incapacity of a

FWC Member that occurred before or after the commencement of Schedule 3. This

means that a FWC Member may be subject to scrutiny by a commission appointed by

the Houses of Parliament in relation to the FWC Member’s conduct at a time when

they were not aware that they could be subject to scrutiny in this way. (FWC

members would, however, have been aware that their conduct could be scrutinised

by the President, Minister and Houses of Parliament under the current

provisions.)

No justification is given in the Explanatory Memorandum

for the retrospective application of proposed section 641B.

Although laws that retrospectively alter the rights of individuals are not

necessarily unjust, and the Parliament undoubtedly has the power to make laws

with retrospective application, justification for such measures is usually

explicitly provided.

[1]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other

Measures) Bill 2017, p. i.

[2]. Fair Work Act 2009,

subsections 156(2).

[3]. Ibid.,

subsection 134(1).

[4]. Ibid.,

subsections 156(3)–(4).

[5]. RC

McCallum, Towards

more productive and equitable workplaces: an evaluation of the Fair Work

legislation, (Fair Work Act review), Department of Education,

Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR), Canberra, 15 June 2012, p. 112.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Productivity

Commission (PC), Workplace

relations framework, Inquiry report, vol. 1, 76, PC, Canberra, 30

November 2015, p. 3.

[8]. Ibid.,

p. 53 (recommendations 8.1 and 8.3).

[9]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other

Measures) Bill 2017, p. i.

[10]. Fair

Work Act 2009, subsection 134(1).

[11]. Fair

Work Commission, Benchbook:

enterprise agreements, Fair Work Commission website, 3 April

2017, pp. 22, 26-36.

[12]. FW

Act, section 54.

[13]. Ibid.,

subsection 186(1).

[14]. Ibid.,

section 173.

[15]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, Inquiry report, 1(76), op. cit., p. 652.

[16]. FW

Act, section 174.

[17]. See

for example: Fair Work Commission, Notice

of employee representational rights (from 3 April 2017), Fair Work

Commission website, p. 1: ‘If you are a member of a union that is entitled to

represent your industrial interests in relation to the work to be performed

under the agreement, your union will be your bargaining representative for the

agreement unless you appoint another person as your representative or you

revoke the union’s status as your representative.’

[18]. See

for example: Peabody Moorvale Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and

Energy Union (2014) 242 IR 210, [2014]

FWCFB 2042; Serco Australia Pty Limited v United Voice and the Union of

Christmas Island Workers [2015] FWCFB

5618; Cement Australia Pty Limited [2011] FWA 6917

and Re Transit (NSW) Services Pty Ltd T/A Transit Systems [2016] FWC

2742.

[19]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, op. cit., pp. 34–35, 663–667.

[20]. Ibid.,

p. 34.

[21]. Ibid.,

p. 667 (recommendation 20.1).

[22]. M

Cash (Minister for Employment, Women and Minister Assisting the Prime Minister

for the Public Service), Appointment

of the Hon Peter Heerey AM QC to undertake independent review, media

release, 19 October 2015.

[23]. P

Heerey, Report

of inquiry into complaints about the Honourable Vice President Michael Lawler

of the Fair Work Commission and related matters, (Heerey Report),

February 2016, pp. 1–2.

[24]. Heerey

Report, op. cit., pp. 10–12.

[25]. Ibid.,

pp. 10–11.

[26]. Ibid.,

pp. 47–48; the Workplace Relations Act 1996 became the Fair Work

(Registered Organisations) Act 2009.

[27]. This

figure has been calculated by comparing the list of AIRC members as at 15

October 2009 and published on the AIRC website and the list of FWC members as

at 26 May 2017 and published on the FWC website.

[28]. Heerey

Report, op. cit., p. 51.

[29]. Submissions

to Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into the

Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 yearly reviews and other measures) Bill 2017.

[30]. Australian

Council of Trade Unions, Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into

the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill

2017, 7 April 2017, pp. 4–5.

[31]. Fair

Work Commission, Submission

to Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into the

Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 yearly reviews and other measures) Bill 2017,

12 May 2017.

[32]. Queensland

Law Society, Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into

the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill

2017, 20 April 2017, p. 2.

[33]. Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry

into the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 yearly reviews and other measures)

Bill 2017, The Senate, Canberra, May 2017.

[34]. Ibid.,

p. vii.

[35]. Fair

Work Commission, op. cit.

[36]. Labor

Senators, ‘Labor Senators' Additional Comments’, additional comments, Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry

into the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 yearly reviews and other measures)

Bill 2017, op. cit., pp. 17–18.

[37]. Ibid.,

p. 18.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. Ibid.

[40]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 3, 2017, The Senate, 22 March 2017, p. 23.

[41]. Heerey

Report, pp. 10–11.

[42]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Alert

digest, 4, 2012, The Senate, 21 March 2012, pp. 8–11.

[43]. Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny

digest, 3, 2017, The Senate, 22 March 2017, pp. 23–24.

[44]. Ibid.,

p. 24.

[45]. Labor

Senators, ‘Labor Senators' Additional Comments’, additional comments, Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry

into the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 yearly reviews and other measures)

Bill 2017, op. cit., p. 18.

[46]. P

Dutton, ‘Second

reading speech: Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other

Measures) Bill 2017’, House of Representatives, Debates, 1 March

2017, p. 1875.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Australian

Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into

the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill

2017, April 2017, p. i; Australian Industry Group (AIG), Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into

the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill

2017, 10 April 2017, p. 3.

[49]. Australian

Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Inquiry into

the Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures) Bill

2017, 7 April 2017, p. 3.

[50]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other

Measures) Bill 2017, p. i.

[51]. P

Dutton, ‘Second

reading speech: Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other

Measures) Bill 2017’, op. cit., p. 1875.

[52]. The

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at pages i to ix of

the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill.

[53]. Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights, Report,

2, 2017, 21 March 2017, p. 57.

[54]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, op. cit., p. 346.

[55]. Ibid.,

p. 339.

[56]. Ibid.,

p. 346.

[57]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, op. cit., pp. 339 and 346.

[58]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures)

Bill 2017, p. iv.

[59]. Proposed

subsection 157(2A) at item 13 of Schedule 1; Fair Work Act 2009,

subsection 156(4).

[60]. Section

616 of the FW Act.

[61]. Fair

Work Act 2009, sections 157, 12 (definition of FWC) and 575; Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures)

Bill 2017, p. 5.

[62]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures)

Bill 2017, p. 5

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. Ibid.,

p. 6.

[65]. Ibid.,

p. 6.

[66]. Fair

Work Act 2009, subsection 186(2).

[67]. See

for example: Peabody Moorvale Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and

Energy Union (2014) 242 IR 210, [2014]

FWCFB 2042; Serco Australia Pty Limited v United Voice and the Union of

Christmas Island Workers [2015] FWCFB

5618; Cement Australia Pty Limited [2011] FWA 6917 and Re Transit

(NSW) Services Pty Ltd T/A Transit Systems [2016] FWC

2742.

[68]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, op. cit., pp. 34–35, 663–667.

[69]. PC,

Workplace

relations framework, op. cit., p. 34.

[70]. Heerey

Report, op. cit., pp. 10–12.

[71]. Ibid.,

p. 46.

[72]. Subsection

581A(4) of the FW Act.

[73]. Whilst

not explicitly stated, the definition of ‘handle a complaint’ in section 12 of

the FW Act (which includes considering and investigating) would appear

to imply an ability to receive a complaint. As such, it would appear that the

Minister can also receive a complaint directly.

[74]. FW

Act, sections 641A and 642 generally.

[75]. FW

Act, sections 641, 641A and 642.

[76]. Heerey

Report, op. cit., p. 47.

[77]. Ibid.,

pp. 47–48.

[78]. Ibid.,

p. 51. The Act of Settlement 1701 (Imp) arose from the constitutional

battles in England in the 17th Century. It provided the essential foundations

of judicial independence, namely that that judges hold office, not at the

pleasure of the King (or in the Australian context, at the pleasure of the

Executive or Governor-General), but rather held office on the basis of good

behaviour (that is, misbehaviour was the only grounds for the Executive

removing a judicial officer, not the pleasure of the Crown). However, the Act

of Settlement provided that upon the address of both Houses of Parliament

it maybe lawful to remove a judicial officer. This preserved the supremacy of

the Parliament whilst ensuring the Executive could not summarily dismiss

judicial officers, and therefore ensured the independence of the judiciary.

See: J King, ‘Removal

of judges’, Flinders Journal of Law Reform, 2003, 6(2), pp. 169–172;

The Hon Chief Justice Brian Martin AO, MBE, ‘Parliamentary government

under threat from the courts?’, Paper presented to the Australasian Study

of Parliament Group, Northern Territory Chapter, Annual Conference 18-19 July

2003, pp. 10-15; H Evans (ed), Odgers’

Australian Senate Practice, 14th edn, 2016, The Senate, pp. 679–683.

[79]. See

sections 82 and 86 of the Workplace Relations

Act 1996, as at 30 June 2009.

[80]. Heerey

Report, op. cit., pp. 47–48.

[81]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures)

Bill 2017, p. 11.

[82]. Section

3 of the JMIPC

Act.

[83]. Sections

13 and 14 of the JMIPC Act.

[84]. Part

3 of the JMIPC Act.

[85]. Explanatory

Memorandum, Fair Work Amendment (Repeal of 4 Yearly Reviews and Other Measures)

Bill 2017, p. 9.

[86]. Heerey

Report, p. 50.

[87]. Ibid.,

p. 50.

[88]. Ibid.,

p. 51. For an explanation of ‘Act of settlement terms’ see the discussion above

in footnote 78 above.

[89]. This

is because the source of the power in relation to FWC Members would be proposed

subsection 641B(2), that is, the provisions of the JMIPC Act applied

to FWC Members, with the modifications provided for in the table, rather than

section 72 of the Constitution or the JMIPC Act itself.

[90]. Queensland

Law Society, Submission

to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee, op. cit., p. 2.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.