Bills Digest no. 76,

2016–17

PDF version [1171KB]

Don Arthur, Anna Dunkley, Michael Klapdor, Matthew

Thomas

Social Policy Section

22

March 2017

Contents

Glossary

The Bills Digest at a glance

Scrutiny of Omnibus Bills

Purpose of the Bill

Committee consideration

Views on the Bill

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Schedules 1–3—Family payment measures

Purpose of the Schedules

Commencement

Background

Previous committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Concluding comments

Schedule 4—Jobs for Families Child

Care Package

Purpose of the Schedule

Commencement

Background

Key elements of the Jobs for Families

package

Impact of the changes

Stakeholder issues

Changed financial implications

Schedules 5–8—Proportional payment of

pensions outside Australia, cease pensioner education supplement, cease

education entry payment, indexation

History

Background

Previous committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Key issues and provisions

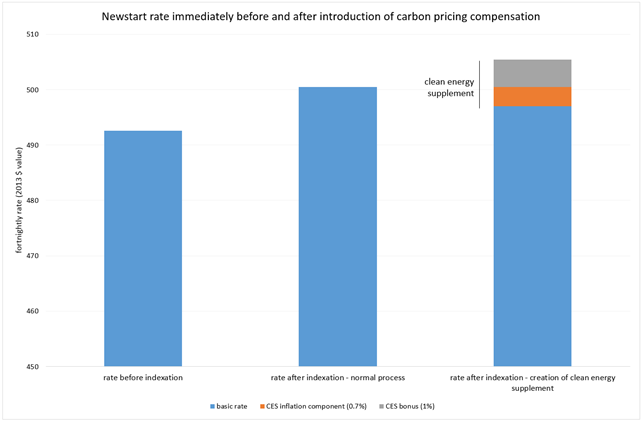

Schedule 9—Closing energy supplement

to new welfare recipients

Background

Rationale for closing off carbon tax

compensation

Previous committee consideration

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 10—stopping the payment of

pension supplement after 6 weeks overseas

Purpose and background

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 11—automation of income

stream review processes

Purpose and background

Policy position of non-government

parties/independent

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Schedule 12—Seasonal horticultural

work income exemption

Commencement

Background

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Key issues and provisions

Schedules 13–16—ordinary waiting

periods, age requirements for various Commonwealth payments, income support

waiting periods and other waiting period amendments (Rapid Activation of young

job seekers)

Schedule 13—ordinary waiting periods

Schedule 14—age requirements for

various Commonwealth payments

Schedule 15—income support waiting

periods

Schedule 16—other

waiting period amendments (Rapid Activation of young job seekers)

Date introduced: 8

February 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Social

Services

Commencement: Various

dates as set out in the table as clause 2 of the Bill (see also the analysis

of each Schedule in this Bills Digest)

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at March 2017.

Glossary

| ACCS |

Additional Child-Care Subsidy |

| ACOSS |

Australian Council of Social Service |

| ATI |

Adjusted taxable income |

| ATO |

Australian Taxation Office |

| AWLR |

Australian Working Life Residence |

| CCB |

Child Care Benefit |

| CCR |

Child Care Rebate |

| CCS |

Child Care Subsidy |

| CPI |

Consumer Price Index |

| DHS |

Department of Human Services |

| DVA |

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

| ECEC |

Early Childhood Education and Care |

| FA Act |

A New Tax System (Family Assistance) Act 1999 |

| FA Admin Act |

A New Tax System (Family Assistance) (Administration) Act

1999 |

| FTB-A |

Family Tax Benefit Part A |

| FTB-B |

Family Tax Benefit Part B |

| Gold Card |

Repatriation Health Card—For All Conditions |

| Greens |

Australian Greens |

| ITAA 1936 |

Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 |

| ITAA 1997 |

Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 |

| Labor |

Australian Labor Party |

| MRC Act |

Military Compensation and Rehabilitation Act 2004 |

| MTAWE |

Male Total Average Weekly Earnings |

| MYEFO |

Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook |

| NSSRN |

National Social Security Rights Network |

| NXT |

Nick Xenophon Team |

| PBLCI |

Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index |

| PES |

Pensioner Education Supplement |

| SS Act |

Social Security Act 1991 |

| SS Admin Act |

Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 |

| SWPP |

Seasonal Worker Preclusion Period |

| TA Act |

Taxation Administration Act 1953 |

| VE Act |

Veterans Entitlements Act 1986 |

The Bills Digest at a glance

The Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Omnibus Savings and Child Care Reform) Bill

2017 (the Bill) passed the House of Representatives on 1 March 2017.

The Bill contains

18 schedules across the Social Services, Education and Training, and Employment

portfolios. Most of the measures proposed are framed as budget savings measures

with some of the intended savings intended to fund the child care measures

proposed in Schedule 4.

This Bills Digest

provides background and analysis for each of the Schedules separately. Where

there are no significant changes from previously proposed provisions, the Bills

Digest provides references to previous Bills Digests or analysis in other

Parliamentary Library publications. Due to timing pressures related to

Parliamentary debate of the Bill, Schedules 17 and 18 are not analysed in this

Digest. It is intended that an updated Bills Digest that includes those schedules

will be provided shortly.

As shown in the

Table 1, many of the measures have been previously introduced to Parliament and

many are currently proposed in other Bills before the Parliament. Table 1 sets

out each of the Schedules and the most recent Bill in which the measures have

been proposed.

Table 1:

Schedules previously introduced

| Schedule |

Previously introduced (most recent Bill only) |

| 1—Payment rates |

Revised version of measures in the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures) Bill 2016, currently before the House of

Representatives. |

| 2—Family tax benefit Part B rate |

Revised version of measures in the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures) Bill 2016, currently before the House of

Representatives. |

| 3—Family tax benefit supplements |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures) Bill 2016, currently before the House of

Representatives. |

| 4—Jobs for families child care package |

Family

Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill

2016 currently before the House of

Representatives. |

| 5—Proportional payment of pensions outside Australia |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 6—Pensioner education supplement |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 7—Education entry payment |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 8—Indexation |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 9—Closing energy supplement to new welfare recipients |

Part of the Budget

Savings (Omnibus) Bill 2016, which passed both Houses on 15 September

2016 following Government amendments which removed these measures. |

| 10—Stopping the payment of pension supplement after 6

weeks overseas |

Not previously introduced to Parliament (announced in the Mid-Year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2016–17, p. 194). |

| 11—Automation of income stream review processes |

Not previously introduced to Parliament (announced in the Mid-Year Economic

and Fiscal Outlook 2016–17, p. 192). |

| 12—Seasonal horticultural work income exemption |

Not previously introduced to Parliament (announced in the Mid-Year Economic

and Fiscal Outlook 2016–17, p. 195). |

| 13—Ordinary waiting periods |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Youth Employment) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 14—Age requirements for various Commonwealth payments |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Youth Employment) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 15 –Income support waiting periods |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Youth Employment) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives. |

| 16—Other waiting period amendments |

Part of the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Youth Employment) Bill 2016, currently

before the House of Representatives |

| 17—Adjustment of parental leave pay for primary carer pay

and other amendments |

An earlier version of this measure was part of the Fairer

Paid Parental Leave Bill 2016 currently before the House of Representatives. |

| 18—Removal of parental leave pay mandatory employer role |

Part of the Fairer

Paid Parental Leave Bill 2016 currently before the House of

Representatives. |

The measures proposed in Schedules 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 13,

14 and 15 have their origin in the 2014–15 Budget. Schedules 4, 5, 16 and 17

have their origin in the 2015–16 Budget. Schedule 9 was included in the 2016–17

Budget and Schedules 10, 11 and 12 were announced in the 2016–17 Mid-Year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook. The Coalition has attempted to introduce a measure

similar to that proposed in Schedule 18 a number of times including whilst it

was in Opposition in 2010.[1]

Scrutiny of Omnibus Bills

The Bill proposes a wide range of amendments to various

statutes in the Social Services, Education and Training, and Employment

portfolios. Many of these amendments are complex. The measures proposed in

Schedule 4 are the most significant changes to child care fee assistance

arrangements in more than 16 years. The Bill bundles complicated, unrelated and

wide-ranging measures together. This may reduce the ability of the Parliament

to properly scrutinise and assess the proposed amendments.

While some of the measures have been proposed and

scrutinised previously, many of these have been revised and others are

completely new measures. Details of any revisions to previously proposed

provisions have not been explicitly identified in the Explanatory Memorandum or

in the joint departmental submission to the Senate Community Affairs

Legislation Committee’s inquiry into the Bill.[2]

The Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee has previously

recommended that the Explanatory Memorandum to an Omnibus Bill should identify

whether measures are new or whether they reflect a measure as it has been

previously introduced on the grounds that ‘this would enable Senators and

others with an interest in the matters covered in the Bill to quickly identify

which measures are completely new and have not yet been considered by the

Parliament’.[3]

The Explanatory Memorandum to this Omnibus Bill does not provide such

information.

Purpose of the Bill

The purpose of the Social Services Legislation Amendment

(Omnibus Savings and Child Care Reform) Bill 2017 (the Bill) is to amend

various Acts to:

- from 1 July 2018, increase the standard fortnightly rate of

Family Tax Benefit Part A (FTB-A) by $20.02 per child, and increase the rate of

Youth Allowance and Disability Support Pension for those aged under 18 years

and living at home by $19.37 (Schedule 1)

- from 1 July 2017, remove eligibility for Family Tax Benefit Part

B (FTB-B) for single parents from 1 January of the calendar year in which their

youngest child turns 17 (with parents aged 60 years or more and

grandparent/great-grandparent carers exempt) (Schedule 2)

- from 1 July 2016, phase out the FTB-A and FTB-B end-of-year

supplement amounts:

- the

FTB-A supplement will be reduced from $726.35 to $602.25 for the 2016–17

financial year; to $302.95 for the 2017–18 year; and abolished from 1 July 2018

- the

FTB-B supplement will be reduced from $354.05 to $302.95 for the 2016–17

financial year; to $153.30 for the 2017–18 year; and abolished from 1 July 2018

(Schedule 3)

- to introduce the following elements of the Government’s Jobs for

Families Child Care Package:

- a

new child care fee assistance payment, the Child Care Subsidy (CCS), replacing

two current payments: Child Care Benefit (CCB) and Child Care Rebate (CCR)

- a

new supplementary payment, the Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS), which

provides additional financial assistance for children at risk of abuse or

neglect, families experiencing temporary financial hardship, families

transitioning to work from income support, grandparent carers on income

support, and low income families in certain circumstances. The ACCS partly

replaces a number of current payments including Special Child Care Benefit,

Grandparent Child Care Benefit and the Jobs, Education and Training Child Care

Fee Assistance payment

- an

enhanced compliance framework.

The new payments are to commence

from July 2018, while some aspects of the new compliance framework will be

introduced from Royal Assent (Schedule 4)

- reduce the period a pensioner can spend overseas before their payment

may be reduced under the Australian Working Life Residence proportionality rules

from 26 weeks to six weeks (Schedule 5)

- cease payment of the Pensioner Education Supplement (Schedule

6)

- cease payment of the Education Entry Payment (Schedule 7)

- pause the indexation of income free areas for all working age

allowances (other than student payments) and for parenting payment single; and

pause the indexation of income free areas and other means test thresholds for

student payments, including the student income bank limits (Schedule 8)

- close off the Energy Supplement to new recipients of affected

payments from 20 September 2017, and cease payment of the Energy Supplement on

20 September 2017 for those who first received the Energy Supplement on or

after 20 September 2016. Those in receipt of the Energy Supplement prior to 20 September

2016 who continue to satisfy eligibility criteria will still receive the

payment after 20 September 2017 (Schedule 9)

- cease payment of the pension supplement once a pensioner has been

outside Australia continuously for six weeks, or when they leave Australia

if departing permanently (Schedule 10)

- allow the Department of Human Services to automatically collect

certain information from income stream providers on a regular basis in order to

conduct income reviews (Schedule 11)

- provide for a trial of an income test incentive aimed at

encouraging job seekers on income support to undertake seasonal horticultural

work and payment of a $300 travel allowance if they undertake horticultural work

that is more than 120 kilometres from their home (Schedule 12)

-

make the following changes to the ordinary waiting period

requirements:

- extend

the ordinary waiting period of seven days to recipients of Parenting Payment

and Youth Allowance (Other)

- provide

for the current exception to the ordinary waiting period to apply on the basis

that a person is in severe financial hardship and that

the person is experiencing a personal financial crisis, making it a more

stringent test and

- clarify

that the ordinary waiting period is to be served after certain other relevant

waiting periods or preclusions have ended (Schedule 13)

- raise, from 22 to 25 years, the eligibility age for Newstart Allowance

and Sickness Allowance (Schedule 14)

-

introduce a four-week waiting period for new claimants of Youth

Allowance (Other) and Special Benefit who are under 25 years of age (Schedule

15)

-

require people subject to the four-week waiting period to

participate in a RapidConnect Plus rapid activation strategy (Schedule 16)

- reduce or remove access to government-funded parental leave pay

for workers who receive paid primary carer leave from their employer (Schedule

17) and

-

remove any requirement for employers to administer

government-funded parental leave pay (Schedule 18).

Committee consideration

On 9 February 2017, the Bill was referred by the Senate to

the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 20 March

2017. The Committee was granted an extension and reported on 21 March 2017.[4]

Details of the inquiry are available from the inquiry

homepage.[5]

The Senate

Scrutiny of Bills Committee reported on some elements of the Bill,

specifically Schedules 3, 4, 9 and 13.[6]

In particular, the Committee reiterated previous concerns and comments it had

made in regards to elements of the child care changes in Schedule 4.[7]

Views on the Bill

Public debate on the Bill has largely focused on particular

Schedules, rather than the Bill as a whole. Information on the policy positions

of non-government parties, independents and major stakeholders relating to

particular measures is provided in the discussion of each Schedule.

Financial implications

Table 2 sets out the estimated impact of each measure on the

fiscal balance as detailed in the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill.

Table 2: financial impact of the

Bill over the forward estimates, 2016–17 to 2019–20 ($ million)

| Schedule |

Title |

Indicative

Financials |

| 1 |

Payment rates |

-2,373.5 |

| 2 |

Family tax benefit Part B rate |

440.6 |

| 3 |

Family tax benefit supplements |

4,653.0 |

| 4 |

Jobs for families child care package* |

-1,290.9 |

| 5 |

Proportional payment of pensions outside Australia |

213.9 |

| 6 |

Pensioner education supplement |

201.0 |

| 7 |

Education entry payment |

42.3 |

| 8 |

Indexation |

69.0 |

| 9 |

Closing energy supplement to new welfare recipients |

933.4 |

| 10 |

Stopping the payment of pension supplement after 6 weeks

overseas |

123.6 |

| 11 |

Automation of income stream review processes |

38.1 |

| 12 |

Seasonal horticultural work income exemption |

-27.5 |

| 13 |

Ordinary waiting periods |

189.4 |

| 14 |

Age requirements for various Commonwealth payments |

431.3 |

| 15 |

Income support waiting periods |

169.5 |

| 16 |

Other waiting period amendments |

-0.8 |

| 17 |

Adjustment of parental leave pay for primary carer pay and

other amendments |

491.2 |

| 18 |

Removal of parental leave pay mandatory employer role |

*Including measures not requiring legislation, the Jobs for

Families Child Care Package totals -$1,663.5.

Source: Explanatory

Memorandum, Social Services Legislation Amendment (Omnibus Savings and Child

Care Reform) Bill 2017, p. 6.

Information on the financial implications of particular

measures is provided in the discussion of each Schedule.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[8]

Information on the human rights implications of particular measures may be

provided in the discussion of each Schedule.

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing, the Parliamentary Joint Committee

on Human Rights had not reported on the Bill.[9]

Schedules 1–3—Family payment measures

Purpose of the Schedules

Schedules 1–3 propose amendments to the A New Tax System

(Family Assistance) Act 1999 (the FA Act), the A New Tax System

(Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 (the FA Admin Act),

the Social

Security Act 1991 (the SS Act) and the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Family Assistance Alignment and Other Measures) Act 2016

to implement the following measures:

- from 1 July 2018, increase the standard fortnightly rate of

Family Tax Benefit Part A (FTB-A) by $20.02 per child in the family aged up to

19, and increase the rate of Youth Allowance and Disability Support Pension for

those aged under 18 years and living at home by $19.37 (Schedule 1)

-

from 1 July 2017, remove eligibility for Family Tax Benefit Part

B (FTB-B) for single parents from 1 January of the calendar year in which their

youngest child turns 17 (with parents aged 60 years or more and

grandparent/great-grandparent carers exempt) (Schedule 2)

- from 1 July 2016, phase out the FTB-A and FTB-B end-of-year

supplement amounts:

- the

FTB-A supplement will be reduced from $726.35 to $602.25 for the 2016–17

financial year; reduced further to $302.95 for the 2017–18 year; and abolished

from 1 July 2018

- the

FTB-B supplement will be reduced from $354.05 to $302.95 for the 2016–17

financial year; reduced further to $153.30 for the 2017–18 year; and abolished

from 1 July 2018 (Schedule 3).

Commencement

Schedule 1 commences on 1 July 2018.

Schedule 2 commences on 1 July 2017.

Part 1 of Schedule 3 commences on 1 July 2016, Part 2 on 1

July 2017, Part 3 on 1 July 2018 and Part 4 on Royal Assent.

Background

FTB-A and FTB-B are the two main forms of direct financial

assistance the Commonwealth provides to families with children. Both payments

are means tested to target assistance at lower-income families. FTB-A is

available to all families who meet the care, residence and income test requirements.[10]

Different income test requirements for FTB-B restrict the payment to single

parent families and couple families where one parent has a low income or is not

in paid employment.[11]

Coalition

has been attempting to implement savings measures since 2014

Since the Coalition won Government in 2013, it has proposed

a range of savings measures targeting the Family Tax Benefit program. Some have

passed, others have been revised, and some have stalled in the Parliament. In

the 2015–16 Budget, the Government linked proposed Family Tax Benefit savings

measures from the 2014–15 Budget with its Jobs for Families Child Care Package.[12]

2014–15

budget measures

In the 2014–15 Budget, the Abbott Government proposed a

range of savings measures targeting Family Tax Benefit Part A (FTB-A) and

Family Tax Benefit Part B (FTB-B). These included:

- lowering the income cut-off point for FTB-B for single parents

and primary earners in a couple from $150,000 per annum down to $100,000 per

annum

-

limiting FTB-B to families with a child under six years

- introducing a new FTB allowance for single parents on maximum

rate of FTB-A who have a child aged six to twelve years, worth $750 per child,

to partially makeup for the loss of access to FTB-B

-

limiting the FTB-A Large Family Supplement to families with four

or more children (increased from three or more children)

-

maintaining FTB payments for two years, that is, they would not

be indexed

-

not indexing some of the FTB-A and FTB-B income test thresholds

for three years

- removing the FTB-A ‘per child add-on’, a component of the FTB

income test which reduced the payment withdrawal rate for those with more than

one child and

-

reducing the FTB-A and FTB-B supplements to their 2004 values

($600 per FTB-A child and $300 per FTB-B family).[13]

The Government attempted to enact these measures, together

with a range of other social security measures, in two Omnibus Bills: the

Social Services and Other Legislation Amendment (2014 Budget Measures No. 1)

Bill 2014 (the No. 1 Bill) and the Social Services and Other Legislation

Amendment (2014 Budget Measures No. 2) Bill 2014.[14]

Neither of these Bills proceeded beyond the second reading stage in the Senate,

most likely because the Government was unable to secure their passage due to

opposition to various measures from the Australian Labor Party (Labor), the

Australian Greens (the Greens), minor parties and independent senators. Both

Bills were discharged from the Notice Paper in the Senate on 28 October 2014.

On 2 October 2014, the Government reintroduced the

measures in four new Bills. The family payments measures were contained in the

Social Services and Other Legislation Amendment (2014 Budget Measures No. 4)

Bill 2014 (the No. 4 Bill) and the Social Services and Other Legislation

Amendment (2014 Budget Measures No. 6) Bill 2014 (the No. 6 Bill).[15]

The No. 6 Bill contained the measures that the Opposition had offered to

support. The No. 6 Bill passed both Houses on 17 November 2014. The family

payment measures it included were:

- the limit on the Large Family Supplement to families with four or

more children

- the removal of the FTB-A per child add-on and

- the lowering of the income cut-off point for FTB-B for single

parents and primary earners in a couple from $150,000 per annum down to

$100,000 per annum.

The remaining measures were included in the No. 4 Bill.

2015–16

Budget—measures linked to child care package

In its 2015–16 Budget, the Abbott Government included its

stalled measures and announced that it would move to abolish the Large Family

Supplement altogether.[16]

The Government also linked the savings from the 2014–15 family payment budget

measures with funding for its Jobs for Families Child Care Package.[17]

Measures

were revised at the same time as the child care package was revised

In October 2015, the proposed FTB savings measures were

revised, together with a revision of the proposed child care package. In

introducing the Bill containing the revised FTB measures, the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation

Measures) Bill 2015, the Minister for Social Services, Christian Porter, stated

that it would ‘supersede measures’ that had stalled in the Senate (the

remaining 2014–15 budget measures).[18]

The savings from the measures proposed in the Bill were

again linked with the 2015–16 Budget’s childcare measures.[19]

The revised FTB savings measures, as proposed in the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures) Bill 2015 were:

-

from 1 July 2018, increase the maximum fortnightly rate of FTB-A

by $10.08 and increase by $10.44 per fortnight the rate of Youth Allowance for

those aged under 18 and living at home, and the rates of Disability Support

Pension (DSP) paid to a single recipient aged under 18 who is living in their

parent’s home due to a medical condition

- from 1 July 2016:

- increase

the standard rate of FTB-B by $1,000.10 per year for families whose youngest

child is aged under one

- reduce

the rate of FTB-B for single parents with a youngest child aged 13–16 to $1,000.10

per annum (from the 2015–16 rate of $2,784.95 per annum) and remove FTB-B in

respect of children aged 17–18

- reduce

the rate of FTB-B for grandparent carer couples with a youngest child in their

care aged 13–16 to $1,000.10 per annum and remove FTB-B in respect of children

17–18 and

- remove

FTB-B for couple families (other than grandparent carers) with a youngest child

aged 13 or over

- phase out the FTB-A and FTB-B supplements by:

- reducing

the FTB-A supplement from the 2015–16 rate of $726.35 per child to $602.25 for

2016–17, to $302.95 for 2017–18 and removing the supplement from 1 July 2018

- reducing

the FTB-B supplement from the 2015–16 rate of $354.05 per family to $302.95 for

2016–17, to $153.30 for 2017–18 and removing the supplement from 1 July 2018.[20]

One measure

was passed with Labor support

After negotiations with Labor, the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation

Measures) Bill 2015 was amended to remove all of the measures except the

measure to remove FTB-B for couple families whose youngest child was aged 13

years or above (with grandparent and great-grandparent carers exempt).[21]

The amended Bill was passed on 30 November 2015 and the resulting Act received

Royal Assent on 11 December 2015.[22]

Remaining

measures stalled

On 2 December 2015, the measures were reintroduced with some

small amendments, in the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments

Structural Reform and Participation Measures) Bill (No. 2) 2015 (2015 No. 2

Bill).[23]

This Bill exempted single parents aged 60 years or over and grandparent carer

couple families from the FTB-B rate reduction measures (and allowed these

recipients to continue receiving FTB-B for children aged 17 or 18).

The 2015 No. 2 Bill passed the House of Representatives on 10 February

2016 and was introduced into the Senate on 22 February 2016. The No. 2

Bill was not debated in the Senate and lapsed on 17 April 2016, at prorogation

of the Parliament prior to the 2016 Federal election.

2016 Bill

On 1 September 2016, a new Bill, the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation

Measures) Bill 2016 (the 2016 Bill), was introduced into the Parliament.[24]

The 2016 Bill contained similar provisions to the 2015 No. 2 Bill except that

the commencement date was pushed back from 1 July 2016 to 1 July

2017.

This Bill has not been debated and remains before the House

of Representatives.

Budget

Savings (Omnibus) Act 2016 changes

As part of an agreement between the Government and Labor to

secure passage of the Budget Savings (Omnibus) Bill 2016, an income limit of

$80,000 was placed on the FTB-A supplement commencing 1 July 2016.[25]

This means that only families with adjusted taxable income below $80,000 are

eligible to receive the FTB-A supplement.

The Government stated that despite this new limit, it would

proceed with the proposal to phase out the supplements altogether via the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures) Bill 2016.[26]

Another element of the agreement to secure passage of the

Budget Savings (Omnibus) Bill 2016 was that the Government would not proceed

with the increase in FTB-B rates for families whose youngest child is aged less

than one year. This measure had been described as a new ‘baby bonus’.[27]

New

measures

The measures

proposed in Schedules 1–3 of the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Omnibus

Savings and Child Care Reform) Bill 2017 were announced on the day the Bill was

introduced. When compared with the 2016 Bill, the proposed measures essentially

double the fortnightly rate increase for FTB-A, remove the reduction in FTB-B

for single parents whose youngest child is aged 13–16, and no longer include

the increase in FTB-B for families whose youngest child is aged under one.

While the measures in the 2016 Bill were expected to save around $5.8 billion

over the forward estimates, the measures in Schedules 1–3 of this Bill are

expected to save around $2.7 billion.[28]

A significant part of the reduction in the fiscal impact between the two Bills

is due to the income limit on the FTB-A supplement that was introduced by the Budget Savings

(Omnibus) Act 2016 (which reduced the number of families eligible for

the supplement and which was expected to provide savings of $1.6 billion over

the forward estimates).[29]

The other major reason for the reduction in savings is the additional increase

in the maximum fortnightly FTB-A rate.

Previous committee consideration

The 2016 Bill, together with the Family Assistance

Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016, was

referred to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee for

inquiry. The Committee tabled its report on 10 October 2016.[30]

The report of the Committee noted the earlier inquiries

into the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments Structural

Reform and Participation Measures) Bill 2015 and the Social Services Legislation

Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation Measures) Bill

(No. 2) 2015 by the Senate Community Affairs Committee and that the key issues

held by stakeholders had been established by these inquiries.[31]

The Committee noted the concerns raised by stakeholders over the coupling of

the savings measures in the 2016 Bill with the additional funding for the Jobs

for Families Child Care Package but considered that this was justified.[32]

The Committee recommended both Bills be passed without amendment. Labor and

Greens Senators dissented from the majority report.[33]

The Bills Digest to the 2016 Bill provides a summary of

the previous committee inquiries into the related Bills.[34]

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Labor has stated that it is opposed to the measures in

Schedules 1–3. Shadow Minister for Families and Social Services, Jenny Macklin

stated:

Labor will not support these cuts to family tax benefits, we

think that the Government is going to hurt millions of Australian families with

these cuts. These cuts will see some of the poorest families in Australia lose

more money. If you’re a family on Family Tax Benefit Part A it will mean that

you are around $200 a year per child worse off. If you’re receiving Family Tax

Benefit Part B you’ll be around $350 a year worse off as a family. These are

real cuts to families. It will leave a million families worse off as a result

of these cuts.[35]

The Greens have made critical comments on the measures in

Schedules 1–3 but have not stated their position on the Bill per se.

Greens spokesperson on Community Services, Senator Rachel Siewert stated:

... the Government is claiming those on FTB A will get an

increase to their payment, that is not true. If you would have received the

full FTB A supplement, you lose out on $8 a fortnight.

Those on FTB B may also miss out, potentially losing up to

$13 a fortnight. To struggling families I would say: don’t let the Government

fool you.

The Government is unrelentingly going after young families,

and those relying on our social security safety net.

We will continue to scrutinise this legislation when it comes

through the Senate.[36]

The Greens made commitments in the 2016 Election to oppose

Coalition ‘cuts to family payments’ and to actually reverse cuts that had

already been made.[37] In

their Dissenting report to the Senate Education and Employment Committee’s

inquiry into the 2016 Bill, Greens Senators recommended that the 2016 Bill be

rejected.[38]

It is unclear what the position of the other crossbench

Senators is in regards to Schedules 1–3. Senators Xenophon and Lambie have both

stated concerns with the Bill in general.[39]

Position of major interest groups

The Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) has stated

that it is opposed to the Bill. In regards to the Family Tax Benefit measures,

ACOSS Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Cassandra Goldie stated:

The so-called concessions the Government has made will be

wiped out by other changes in the Bill, leaving many low-income people worse

off.

Of course we all want greater support for families to get

better quality childcare but it cannot be funded on the backs of some of the

most disadvantaged people in our country.

This is not the way to build a strong community – caring for

each other through all stages of our lives has served our nation well. This new

Bill risks weakening our social fabric.

The increase to the Family Tax Benefit Part A for families

with children by $10 a week does not make up for cuts to the supplements. A

sole parent with two children aged 13 and 15 will still lose between $14 and

$20 per week, or around $1,000 a year.

Although this is less of a hit than under the previous

proposal, it will still severely impact single parents, most of whom are

struggling to keep a roof over their heads and feed their children as well as

provide for them in the new school year.[40]

The National Social Security Rights Network (NSSRN) stated

that it was opposed to the measures:

The net impact of these changes is to reduce payments to

families. Although there is an increase to the fortnightly rate of FTB-A of

about $20 per fortnight for the majority of families, this is more than offset

by the loss of the FTB-A supplement from 1 July 2018, currently $726 per child

per year.

Single parents and single income families with pre-school and

primary school age children will lose more, as they also lose the FTB-B

supplement, currently $354 per year per family. Single parent families with

older children in year 11 or year 12 (depending on the child’s age) will lose

even more, as they lose eligibility for FTB-B entirely from the end of the year

their child turns 16.

For the majority of families receiving FTB, who have

household incomes under $80,000, this is a loss of income support of at least

$200 per year per child, more if they are a single parent. If this Bill

proceeds, the impact will be even harsher because other measures in it will

further cut the incomes of the poorest families in our community.

Close to half of all families receiving FTB also receive an

income support payment (such as parenting payment, carer payment or disability

support pension). The closure of the energy supplement to new social security

recipients will further cut the income of those households by between $228 and

$366 per year (at current rates).

The NSSRN opposes these cuts. They are harsh and unfair and

affect the poorest families in our community. Cuts of this kind need a very

strong rationale, which the Government has not provided.[41]

Other community sector groups have also criticised the measures.

Benevolent Society CEO, Jo Toohey, stated:

For those relying on the aged pension [referring to other

Schedules in the Bill] and family supports as their sole source of income,

these cuts will hurt. They will drive older people further into poverty and

will continue to entrench the disadvantage of Australia’s most vulnerable

families.[42]

Ms Toohey described the Bill as ‘appalling’ as it ‘pits

different groups in the community against each other’.

Financial implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, the

amendments in Schedules 1–3 will provide net savings of $2.7 billion over the

forward estimates 2016–17 to 2019–20.[43]

The measures will see increased expenditure of $2.4 billion for the increase in

the FTB-A standard rate and the related Youth Allowance/Disability Support

Pension rates. This will be offset by savings of $440.6 million for the FTB-B

eligibility changes, and $4.7 billion from the phasing out of the FTB-A

and FTB-B supplements.[44]

Key issues and provisions

While the measures in Schedules 1–3 are modified versions of

those previously proposed in the three ‘Family Payments Structural Reform and

Participation Measures’ Bills, the key issues remain the same as those

discussed in the Bills Digest for the Social Services Legislation Amendment

(Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation Measures) Bill 2015.[45]

The key issues are:

- the measures will see rate reductions for FTB-A and FTB-B

recipients, as the abolition of the end-of-year supplements more than offsets

the proposed fortnightly rate increases

-

it is unclear if the new income reporting system will make the

end-of-year supplements redundant and

- the measures will further complicate the family assistance

payment system, despite one of the rationales being the simplification of the

system.

Rate

reduction

All FTB-A recipients with family income under $80,000 and

all FTB-B recipients will, over time, receive reduced payments. This is because

the increase in maximum FTB-A rates (proposed by Schedule 1) are more than offset

by the soon-to-be-phased out FTB-A supplements (and the FTB-B supplement

withdrawal is not being offset by any rate increase). FTB-A recipients with

income over $80,000 have already lost eligibility for the FTB-A supplement as a

result of amendments by the Budget Savings (Omnibus) Bill 2016.

The increase in fortnightly rates is equivalent to around

$522 per child per annum if in receipt of the maximum rate. The FTB-A

supplement is currently worth $726.35 per child per annum. This will mean a

rate reduction of around $204 per child for those receiving the maximum rate.

FTB-B recipients (single parents and couple families with

one low-income earner) will lose the full amount of the FTB-B supplement. Most

FTB-B recipients also receive FTB-A so the impact of these measures on their

income will be compounded. Single parents whose youngest child is turning 17

will also lose eligibility for the payment altogether. Based on current rates,

this would amount to a loss of $3,186.45 in FTB-B for the financial year (including

the end-of-year supplement). The design of the measure means that single

parents would lose eligibility for FTB-B from 1 January of the year in

which their youngest child turns 17, even if the child’s birthday is on 31

December of that year.

The role of

the end-of-year supplements in minimising debts

The supplements were not included in the FTB program

introduced in 2000. They were introduced later (the FTB-A supplement in 2004

and the FTB-B supplement in 2005).[46]

While described at the time as an increase in the rates of FTB, the design of

the supplements as lump-sums paid at the end of the financial year was mainly

in response to the large number of FTB recipients who ended up with small

debts. Debts arose as the vast majority of FTB recipients choose to be paid by

way of fortnightly instalments during the year, rather than claiming a lump-sum

at the end of the year when they lodge their tax return. When an FTB recipient

is paid by instalment, they are required to estimate their adjusted taxable income

(ATI) for the year of payment and the rate of FTB paid is based on their

estimate. Once the financial year finishes and they lodge their tax return,

their actual ATI (as assessed) is reconciled against the FTB paid to them for

the year. As it is often difficult to estimate ATI over the year ahead, many

families end up either underpaid (and then paid their arrears) or overpaid

(thereby creating a recoverable debt).

While the supplements are included in an individual’s

total FTB entitlement calculation, the value of the supplement is not paid

until after the reconciliation process. As such, it can be used to offset any

debts (partly or in full). Tax return payments from the Australian Taxation

Office (ATO) can also be withheld to offset any debts. If any debt amount

remains, fortnightly payment rates for the following year can be reduced to

recover the outstanding amount (or other debt recovery actions can be taken if

the person is no longer entitled to FTB). If the reconciliation process finds

that a person has been underpaid, then any supplement entitlement will be added

to the amount outstanding and paid as a top-up payment.[47]

The Government holds that such debts will not be an issue

in the future as the ATO is introducing a ‘single touch payroll system’.[48]

This system is intended to automatically report payroll information to the ATO

that can be shared in ‘real-time’ with the Department of Human Services (DHS),

allowing DHS to make adjustments to an individuals’ FTB entitlements if there

are any discrepancies with the individual’s income estimate for the year. The

system is intended to be implemented from 1 July 2017, with employers with 20

employees or more required to use the system from 1 July 2018.[49]

There is an element of risk involved in removing the supplements

before it is clear that the system will work as intended to minimise debts.

Also, not all employers will be required to use the single touch payroll system

meaning that many families will still be reliant on the current arrangements.

Complicated

rate structure

In his second reading speech to the Bill, the Minister for

Social Services, Christian Porter, stated: ‘While the changes to family

payments in this Bill will pay for the Jobs for Families Child Care Package,

they will also simplify the Family Tax Benefit system ... ’.[50]

While removing the FTB supplements does simplify the system, the proposed

changes to FTB-B rates and the changes made via the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Family Payment Structural Reform and Participation

Measures) Act 2015 and the Budget Savings

(Omnibus) Act 2016 will add complexity to the rate structure and

eligibility conditions for family assistance payments:

- In 2015–16 there were two different FTB-B rates available to

eligible families, with a different income test applying to single parent and

couple families but with other eligibility conditions the same. As a result of

recent changes, there are now different eligibility conditions for couple

families and for single parent, grandparent and great-grandparent families:

couple families who are not grandparent or great-grandparent carers are no

longer eligible for FTB-B if their child is aged 13 or over.

-

As a result of the Budget Savings (Omnibus) Act 2016,

different payment rates are payable for FTB-A and FTB‑B depending on when

a person commenced receiving the payments. Those eligible for FTB-A or FTB-B on

19 September 2016 can receive the Energy Supplement and can continue to

receive it if they remain eligible for their FTB payment. Those who became

eligible for FTB-A or FTB-B between 20 September 2016 and 19 March 2017

are eligible to receive the Energy Supplement up to 19 March 2017—they will no

longer receive the Energy Supplement from 20 March 2017. Those who become

eligible for FTB from 20 March 2017 will not receive an Energy Supplement.

- Also as a result of the Budget Savings (Omnibus) Act 2016,

those in receipt of FTB-A with family income over $80,000 per annum will not be

entitled to the FTB-A supplement. This can mean a family with income just over

$80,000 can have an FTB-A entitlement hundreds (and potentially thousands) of

dollars less per annum than a family with income just under $80,000.

- The proposed changes in the Bill will add another eligibility

category so that couples, single parents and grandparent/great-grandparents and

those aged 60+ will each have different eligibility criteria based on the age

of their youngest child.

Key

provisions of Schedule 1—Payment rates

A New Tax

System (Family Assistance) Act 1999

Item 1 inserts proposed clause 7 at

Part 2 of Schedule 4 of the FA Act to provide for a one-off increase in

the standard per child rates of FTB-A of $521.95 (there are two rates: one for

an FTB child aged under 13 years and one for an FTB child who has reached 13

years). This will increase the maximum annual rate of FTB-A for 2018-19 on top

of the usual indexation to this rate that occurs on 1 July 2018 and is

equivalent to an additional increase of $20.02 per fortnight.

The standard rate is the maximum rate of FTB-A. The

increase does not apply to other FTB-A rates such as the base rate.

Social

Security Act 1991

Items 3 and 4 substitute the annual and fortnightly

maximum basic rates of Disability Support Pension (DSP) for recipients aged

under-18, with no dependent children, considered not independent and living at

home, currently set out in table item 1 of the table at Point 1066A-B1 of the SS

Act with references to ‘annual linked rate’ and ‘fortnightly linked rate’

respectively. The definitions of the linked rates are inserted by item 6

as proposed points 1066A-B2 and 1066A-B3. The annual linked rate

is the maximum FTB-A rate for an FTB child aged over 13 years (the amount

specified in column 2 of table item 2 in clause 7 of Schedule 1 of the FA

Act). The fortnightly linked rate is worked out by dividing the annual rate

by 365 and multiplying the result by 14. Currently, the DSP rate for those aged

under-18, not independent and living at home is $239.50 per fortnight compared

to the FTB-A rate for children over 13 years of $237.86 per fortnight.[51]

The amendments align the rates of the two payments to ensure these DSP

recipients also benefit from the proposed FTB-A rate increase.

Items 7–10 make similar amendments at point

1066B-B1 for blind DSP recipients aged under-18 in the same circumstances as

the above child, to link the DSP rate for these recipients with the FTB-A rate

for children over 13 years.

Items 11–16 make similar amendments at point

1067G-B2 and 1067G-B3 to link the Youth Allowance rates for those aged

under-18, not considered independent and still living at home and for those

aged under-18, considered independent and living in supported state care, with

the FTB-A rate for children over 13 years. These Youth Allowance rates are

currently the same as the rate for DSP recipients aged under-18, not

independent and living at home ($239.50).

Key

provisions of Schedule 2—Family Tax Benefit Part B rate

A New Tax

System (Family Assistance) Act 1999

Item 1 inserts proposed subparagraphs

22B(1)(a)(ia) and (ib) into the FA Act so that FTB-B will no longer

be payable for secondary school children of single parents in the calendar year

these children turn 17. Single parents aged 60 years or more, and grandparent

or great-grandparent carers of the relevant child are exempt from this

restriction and can continue to receive FTB-B for secondary school children

aged 16, 17 or 18.

Currently, for a parent/carer to be eligible for FTB-B in

respect of a child aged 16 or over, the child must meet the definition of senior

secondary school child at section 22B of the FA Act. This

definition currently allows FTB-B to be paid in respect of children aged 16, 17

or 18 (where the calendar year in which the child turned 18 has not ended) if

they meet the schooling requirements (also set out at section 22B). The new

subparagraphs will amend the definition of secondary school child so that it

refers to the different payment rate categories to be set out in clause 30 of

Schedule 1 to the FA Act (amended by item 7). These rate

categories will distinguish parents/carers of eligible children aged 13 years

or over who are not members of a couple and are aged at least 60 years of age

or are a grandparent/great-grandparent of the child, and parents/carers of

eligible children aged 13 years or over who do not fit these criteria. Proposed

subparagraphs 22B(1)(a)(ia) and (ib) will set different age limits for

the definition of secondary school child depending on whether the child is

under the care of a person aged at least 60 years or a

grandparent/great-grandparent, and those under the care of a single parent who

does not meet these criteria.

Item 7 substitutes proposed clause 30 into

Schedule 1 of the FA Act setting out the different rate categories for

FTB-B. There will be two different rates (one for children aged less than five

years and one for older children) and four family situations which can

determine eligibility for the rates:

1. family

with youngest child aged under five years

2. family

with youngest child aged at least five years but less than 13 years

3. single

parent/carer family with youngest child aged at least 13 years and the

parent/carer is aged 60 years or more; or, single/couple family where the carer

is a grandparent/great-grandparent of that youngest child

4. single

parent/carer family with youngest child aged at least 13 years but less than

17 years where none of the criteria in (3) apply.

Key

provisions of Schedule 3—Family Tax Benefit supplements

Schedule 3 contains four Parts, the amendments in which

will operate to gradually reduce the FTB-A and FTB-B supplements over two years

before abolishing the supplements from 1 July 2018. Items 1–9 make

amendments to the FTB-B supplement amount set out at subclause 31A(2) of

Schedule 1 to the FA Act and the FTB‑A supplement amount

at subclause 38A(3) of Schedule 1 of the FA Act,

and related provisions, to:

- reduce the FTB-B supplement from the current per family rate of

$354.05 to $302.95 on 1 July 2016 (the same rate as when it was introduced),

and then further reduce to $153.30 from 1 July 2017[52]

- reduce the FTB-A supplement from the current per child rate of

$726.35 to $602.25 on 1 July 2016, and then further reduce to $302.95 on

1 July 2017.[53]

From 1 July 2018, items 14 and 17 remove

references to the FTB-A supplement in the method statements at clauses 3 and 25

of Schedule 1 of the FA Act which are used to calculate an individual’s

FTB-A rate. Items 18–20 remove references to the FTB-B supplement

in the rules for calculating an individual’s FTB-B rates at clauses 29 and 29A

of Schedule 1. Items 15 and 16 remove references to the FTB-A supplement

used for calculating an individual’s maintenance income test ceiling, by

repealing a method statement step at clause 24N of Schedule 1 and repealing

clause 24R of Schedule 1. The maintenance income test ceiling is part of the

calculation of how child support payments affect an individual’s FTB rate where

there are both child support and non-child support children in the family, or

where the individual has two or more child support cases.[54] The

maintenance income test ceiling ensures that any child support received only

reduces the above base-rate amounts of FTB-A paid for the child support

children.[55]

Concluding comments

Schedules 1–3 are another attempt at presenting a more

palatable range of FTB savings measures than those previously proposed by the

Government, and those currently before the Parliament in a separate Bill.

Rather than reducing the rate of FTB-B for single parents

with children aged 13 or over by more than $2,000 per annum (as previously

proposed), the measures in Schedules 2 and 3 will allow these parents to

continue to receive the standard FTB-B rate (minus the supplement) until the

year in which their youngest child turns 17. This will still mean that these

single parents may lose eligibility for FTB-B in the final one or two years of

their youngest child’s schooling, but the cuts are smaller than those previously

proposed.

The increase in FTB-A rates proposed in Schedule 1 (double

those previously proposed) will partially offset the impact of phase out of the

end-of-year supplements (in Schedule 3) for many FTB-A recipients. Not all

FTB-A recipients will receive a benefit from the increase: those receiving less

than the base rate will not receive an increase.

Phasing out the supplements carries an element of risk due

to the uncertainty as to whether the ATO’s new income reporting system will

significantly reduce the number of debts that arise in the reconciliation

process.

Overall, the measures deliver significant savings to the

Government but further complicate the family assistance system.

Schedule 4—Jobs for Families Child Care Package

The Bills Digests for the Family Assistance Legislation

Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2015 and the Family

Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill

2016 provide a detailed background and analysis of the measures proposed in

Schedule 4.[56]

There are no significant differences between the provisions in Schedule 4 and

those proposed in the Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for

Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016.

This section of this Bills Digest will only provide a

brief summary of the measures, the legislative history, and a note on the

changed financial implications of the measures.

Purpose of the Schedule

Schedule 4 proposes amendments to the A New Tax System

(Family Assistance) Act 1999 (the FA Act), the A New Tax System

(Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 (the FA Admin Act),

the A New Tax

System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999, the Fringe Benefits

Tax Assessment Act 1986 and the Income Tax

Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) to introduce the following

elements of the Government’s Jobs for Families child care package:

- a new child care fee assistance payment, the Child Care Subsidy

(CCS), replacing two current payments: Child Care Benefit (CCB) and Child Care

Rebate (CCR)

- a new supplementary payment, the Additional Child Care Subsidy

(ACCS), which provides additional financial assistance for children at risk of

abuse or neglect, families experiencing temporary financial hardship, families

transitioning to work from income support, grandparent carers on income

support, and low income families in certain circumstances. The ACCS partly

replaces a number of current payments including Special Child Care Benefit,

Grandparent Child Care Benefit and the Jobs, Education and Training Child Care

Fee Assistance payment

- an enhanced compliance framework.

Commencement

The new payments are to commence from July 2018, while

some aspects of the new compliance framework will commence on the day after

Royal Assent.

Background

The Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for

Families Child Care Package) Bill 2015 was not debated following its

introduction in the House of Representatives on 2 December 2015 and lapsed when

the Parliament was prorogued on 15 April 2016. The Family Assistance

Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016, introduced

on 1 September 2016, has also not been debated.

The Jobs for Families Package was announced in the 2015–16

Budget and is based on recommendations from the Productivity Commission’s

inquiry into childcare and early childhood learning.[57]

The package, when announced, included an additional $3.5 billion in expenditure

on child care assistance over five years.[58]

In December 2015, the Turnbull Government announced that it had revised the

package following consultation with parents and stakeholders and following difficulties

in passing savings measures from the Family Tax Benefit program in the

Parliament (see Background to Schedules 1–3 above).[59]

Key elements of the Jobs for Families package

The new CCS payment provides a subsidy rate based on a

percentage of the actual fee or an hourly benchmark price (whichever is lower).

The benchmark price is different for each service type. The percentage covered

is determined by family income with a subsidy rate of 85 per cent of the

benchmark price or actual fee for families with incomes at or below $65,710 per

annum. This rate tapers by one percentage point for every $3,000 in income over

this threshold to 50 per cent for family incomes at $170,710. A flat subsidy

rate of 50 per cent applies for family incomes between $170,710 and $250,000

and then tapers for incomes over $250,000 until it reaches the base rate of 20

per cent of the benchmark price (for incomes at, or above, $340,000 per annum).

Families with incomes over $185,000 will have their CCS entitlement capped at

$10,000 per child per year.

A three-part activity test determines the number of hours

that can be subsidised:

- 8–16 hours per fortnight of approved activities provides up to 36

hours of CCS per fortnight

- 17–48 hours provides up to 72 hours of CCS and

- more than 49 hours of approved activities provides up to 100

hours of CCS.

For couple families, the partner with the lower number of

hours of activity determines the CCS entitlement. Approved activities include

work, training, study or certain other recognised activities such as

volunteering, as well as participation requirements for income support

payments. Families with incomes of up to $65,000, who do not meet the activity

test, will be eligible to receive up to 24 hours of CCS per fortnight under a

separate program known as the Child Care Safety Net.

The Child Care Safety Net will replace existing funding

programs for service providers and also includes the ACCS. The ACCS will

provide a top-up payment to the CCS for disadvantaged and vulnerable families.

Impact of the changes

The Government estimates that around 815,600 families will

receive a higher level of fee assistance under the changes compared to the

current funding model; around 140,500 families will receive around the same

level of assistance and around 183,900 families will receive a lower level of

assistance.[60]

Alternative modelling by the Australian National University’s Centre for Social

Research and Methods estimated 582,000 families will be better off, around

330,000 families will be worse off and 126,000 families will receive around the

same level of subsidy.[61]

Stakeholder issues

Providers, academics and interest groups are concerned

that the activity test is too complex and will exclude many children from Early

Childhood Education and Care (ECEC). There are also concerns at the new

administrative requirements for providing assistance to children at risk of

abuse and neglect. The design of the CCS payment may also lead to a decline in

the real value of assistance provided to families over time, and significant

child care fee increases will need to be borne by families without additional

assistance from government.[62]

The key recommendation from child care stakeholders has

been an increase in the minimum number of hours of subsidised care available to

lower income families (families who would not meet the activity test

requirements) from the 12 hours per week (as proposed in Schedule 4) to 15

hours per week.[63]

While the Government had previously been opposed to this recommendation, its

responses to the Senate committee inquiries into the 2015 and 2016 Bills (both

provided in February 2017) and the Department of Social Services’ and

Department of Employment and Training’s submission to the Senate Community

Affairs inquiry into the Bill all state that ‘the Government is considering

this proposal as part of its negotiations and deliberations in preparation for

Parliamentary debate’.[64]

This may indicate that the Government is willing to amend one of the more

contentious elements of Schedule 4.

Changed financial implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that Schedule

4 will cost $1.29 billion over the forward estimates, with a note stating that

the total Jobs for Families Child Care Package (including measures not

requiring legislation) will cost $1.66 billion over the forward estimates.[65]

This is a significant reduction in costs from the previous

Jobs for Families Bills. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Family Assistance

Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016 stated that

$3 billion in additional expenditure would be provided to support the

implementation of the package.[66]

The package, when announced, included an additional $3.5 billion in expenditure

on child care assistance over the forward estimates.[67]

Each of these expenditure estimates includes a two-year period of the CCS.

Much of this reduction appears to be based on revised

parameters and other variations. The 2016–17 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal

Outlook (MYEFO) stated that payments related to CCB, CCR and CCS are expected

to decrease by $724 million in 2016–17 and $7.6 billion over the four

years to 2019–20.[68]

The Government’s submission to the Senate Committee inquiry into the Bill

states the downward ‘variation’ included:

- the impact of child care compliance measures that have been implemented

in the past 18 months (notably the Family Day Care child swapping measure);

- a one-off major correction following a complete overhaul of the child

care forward estimates model; and

- using new projection methodologies for growth in child care usage and

fees, rather than a ten year rolling average.[69]

Schedules 5–8—Proportional payment of pensions outside

Australia, cease pensioner education supplement, cease education entry payment,

indexation

The measures in Schedules 5–8 were previously introduced in Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016. The measures in this

Bill are equivalent to those in the earlier Bill.

History

The Government announced the first measure, earlier

proportional payment of pensions outside Australia (Schedule 5), in the 2015–16

Budget.[70]

The remaining three measures were first announced in the 2014–15 Budget. These

are:

- cease pensioner education supplement (Schedule 6)[71]

- cease education entry payment (Schedule 7)[72]

and

- pausing indexation for three years of:

- the

income free areas for all working age allowances (other than student payments)

and for parenting payment single and

- the

income free areas and other means test thresholds for student payments,

including student income bank limits (Schedule 8).[73]

Table 3 sets out previous Bills the measures in Schedules

5–8 have been proposed in.

Table 3:

List of measures and previous Bills where the measure has appeared

Background

Proportional

payment of pensions outside Australia

An income support payment is ‘portable’ when a recipient can

continue to receive the payment when they are overseas. Portability varies by

payment type and the recipient’s circumstances. For most payments portability

is temporary (usually limited to six weeks). However, in most circumstances,

recipients of the Age Pension can continue to receive payment indefinitely.

This is known as unlimited portability.[76]

A limited number of recipients of Wife Pension, Widow B Pension and Disability

Support Pension also have unlimited portability.[77]

While income support recipients with unlimited portability

can continue to receive a payment indefinitely while overseas, those who have

not resided in Australia for at least 35 years (between the age of 16 and

pension age) currently receive a reduced amount after they have been overseas

for more than 26 weeks.

The reduction in payment is based on the period of time

the person has resided in Australia between the age of 16 and pension age. This

is known as their Australian Working Life Residence (AWLR). The payment rate is

calculated by dividing the AWLR by 35. For example, a person who has resided in

Australia for 10 years between 16 and age pension age will usually receive

10/35ths of the full means tested rate.[78]

This reduction in payments is known as ‘proportionality’.

Pensioner

Education Supplement and Education Entry Payment

Pensioner

Education Supplement

The Pensioner Education Supplement (PES) helps eligible

income support recipients meet some of the ongoing costs associated with study.

The rationale for making the payment is to improve recipients’ later employment

prospects.[79]

PES is not means tested and is non-taxable. Depending on

their study load, eligible students receive $62.40 or $31.20 per fortnight.[80]

It is available to recipients of Parenting Payment (single), Disability Support

Pension, Carer Payment, Widow B Pension, Widow Allowance, Wife Pension, and

certain other groups of income support recipients (including recipients of some

Veterans’ Affairs payments).[81]

There is a separate ABSTUDY Pensioner Education Supplement

available to Indigenous income support recipients.[82]

As the ABSTUDY Pensioner Education Supplement is not administered under the SS

Act it is not affected by this measure (ABSTUDY is governed by the ABSTUDY

Policy Manual).[83]

The National Commission of Audit noted that recipients of

the PES received the payment during vacation periods as well as during study

terms or semesters. The Commission recommended ‘that the Supplement only be

provided to recipients during study terms or semesters.’[84]

As at September 2016, there were 37,717 PES recipients.[85]

Education

Entry Payment

The Education Entry Payment is a taxable lump sum payment of

$208 to help recipients meet the up-front costs of education and training. It

is paid once a year.[86]

The National Commission of Audit recommended that the

Education Entry Payment be abolished, partly on the grounds that it duplicated

the assistance available through the PES.[87]

In 2015–16, there were 68,967 recipients of the Education

Entry Payment.[88]

Pause

indexation for three years of income free areas

Indexation of income free areas was explained in the Bills

Digest for the Social Services and Other Legislation Amendment (2014 Budget

Measures No. 1) Bill 2014:

Currently, the income test free area for a single person for

most of the working age income support allowance payments is $100 per

fortnight. The free area is $200 a fortnight (combined) for partnered persons.

Once income is in excess of these free areas in a fortnight, the maximum rate

payable is reduced by 50 cents for each dollar of income over the free area.

Income over $250 in a fortnight reduces the rate by 60 cents in each dollar.

These income test free areas are indexed once a year on 1 July to increases in

the [Consumer Price Index] CPI. The working age income support allowance

payments that use this income test are Newstart Allowance, Widow Allowance,

Partner Allowance and Sickness Allowance.[89]

Since that Bills Digest was published the income free areas

have been indexed. The current income test free area is $104 per fortnight;

payments are reduced by 50 cents for each dollar between $104 and $254, and $75

plus 60 cents for each dollar over $254.[90]

Further background about the indexation of income free areas is available in

the Bills Digest for the Social Services and Other Legislation Amendment (2014

Budget Measures

No. 1) Bill 2014.[91]

Previous committee consideration

Senate

Community Affairs Legislation Committee

On 15 September 2016, the Senate referred the Social

Services Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016 to the Senate

Community Affairs Legislation Committee for inquiry and report. The Committee

reported in October 2016.[92]

The Committee made two recommendations, that the Bill be

passed and that it be amended to include transitional arrangements for current

recipients of the Pensioner Education Supplement, to enable them to complete

their education or training course.[93]

In their Dissenting report, Labor Senators rejected the

majority report’s recommendations and recommended that the Senate reject the

Bill.[94]

Greens Senators also recommended that the Bill not be passed.[95]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had

no comment on the measures proposed in the 2016 Bill or the 2015 Bill. [96]

The Committee had no comment on Schedules 5 to 8 of the current Bill.[97]

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

In their dissenting reports on the Social Services

Legislation Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016 to the Senate Community Affairs

Legislation Committee, Labor and Greens Senators recommended that the Senate

reject the Bill.

Position of major interest groups

All of the measures in these schedules are savings measures.

Much of the criticism from interest groups relates to the idea that the savings

should come at the expense of people who are on low incomes.

As these measures have all been introduced in earlier Bills,

interest groups have outlined their positions in previous submissions. A number

of interest groups made submissions on the Social Services Legislation

Amendment (Budget Repair) Bill 2016 Bill.[98]

None of the interest groups making a submission on the 2016 Bill indicated

support for any of the measures in their current form.

Key issues and provisions

Schedule

5—Proportional payment of pensions outside Australia

This measure was outlined in the Parliamentary Library’s

Budget Review 2015–16:

While most income support payments can only be paid for a

limited period of time if a recipient is overseas (known as the portability of

the payment), the Age Pension, Widow B Pension, Wife Pension and the Disability

Support Pension (in special circumstances) can continue to be paid while a

person is overseas indefinitely and even where an eligible pensioner chooses to

reside in another country. However, if a pensioner is overseas for a period

longer than 26 weeks, their payment rate may be reduced to a proportion of the

time they spent in Australia between the age of 16 years and the age pension