Bills Digest no. 50,

2016–17

PDF version [856KB]

Dr Rhonda Jolly

Social Policy Section

30

November 2016

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill

Background

Early national analysis

Productivity Commission inquiry

Senate Select Committee Report on

Online Gambling

National Office for the Information

Economy (NOIE) report

Enactment of the IGA

Figure 1: types of online gambling

Recent assessments

2010—Productivity Commission Inquiry

report on gambling

2010—Joint Select Committee on

Gambling Reform investigations

2011—Department of Broadband,

Communications and the Digital Economy Review

2013—O’Farrell Review

Committee consideration

Selection of Bills Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

In-play supporters

In-play opponents

Comments to the Environment and

Communications Committee Inquiry into this Bill

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

ACMA Act

IGA

Items 6 to 143 amend

the IGA

New definitions

Prohibited interactive

gambling service

Regulated interactive gambling service

Designated interactive gambling

service

Prohibited internet gambling content

Key issue—penalty amounts

Appendix A: Recommendations of the

O’Farrell Review

Date introduced: 10

November 2016

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Communications

and the Arts

Commencement: Sections

1–3 on Royal Assent; all other provisions on the 28th day after Royal

Assent.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2016.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Purpose of the Bill

- The purpose of the Interactive Gambling Amendment Bill 2016 (the

Bill) is to amend the Interactive

Gambling Act 2001 (IGA) and the Australian

Communications and Media Authority Act 2005 (ACMA Act) in

response to certain recommendations made by the 2015 Review of the impact of

illegal offshore wagering to:

- clarify the law and

- strengthen enforcement powers of the Australian Communications

and Media Authority (ACMA).

Structure of the Bill

- The Bill consists of two Parts:

-

Part 1 amends the IGA to clarify licensing requirements

for interactive gambling services in Australia, to introduce a civil penalty

regime to be enforced by ACMA and to define prohibited interactive gambling

services not to be provided in Australia[1]

- Part

1 also includes proposed changes to the ACMA Act to strengthen ACMA’s

enforcement powers

- Part 2 contains application and transitional provisions.

Background

- The IGA was introduced by the government in response to concerns

about the effects that interactive or online gambling may have on Australians.

- Since its passage, a number of critics of the IGA have

noted that the legislation has done little to prevent the spread of interactive

gambling. Some have argued that its inherent weaknesses have contributed to the

growth of this form of gambling.

- There have been a number of reviews of gambling which have

considered changes to the IGA. This Bill reflects recommendations made

by the most recent review into the impact of offshore wagering.

Stakeholder concerns

- Stakeholders agree that changes need to be made to make

interactive gambling legislation and policy more effective. All appear to agree

that a national co-operative strategy for interactive gambling is called for

and that it should be accompanied by preventative, educative and counselling

measures. There are differences of opinion, however, on the ways that

improvements can be achieved. Some favour a degree of legislative liberalisation

while others call for tougher legislative requirements.

Key issues

- Proposed prohibition of click to call interactive services has

been a key issue of debate. The Bill intends to re-define telephone betting

service specifically to exclude the in-play betting options offered by interactive

betting services. This has been seen by some as enhancing harm minimisation,

while others have argued that the move will be ineffective because of the

popularity of in-play betting online. They claim customers will continue to

gamble offshore regardless.

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Interactive Gambling Amendment Bill

2016 (the Bill) is to amend the Interactive

Gambling Act 2001 (the IGA) and the Australian

Communications and Media Authority Act 2005 (the ACMA Act) in

response to certain recommendations made by a 2015 Review into the impact of

illegal offshore wagering to:

- clarify

the law regarding illegal offshore gambling and

- strengthen

the enforcement powers of the Australian Communications and Media Authority

(ACMA).

Structure

of the Bill

The Bill consists of two Parts:

- Part

1 amends the IGA to clarify licensing requirements for interactive

gambling services in Australia, to introduce a civil penalty regime to be

enforced by ACMA and to define prohibited interactive gambling services not to

be provided in Australia.[2]

It also amends the ACMA Act to strengthen ACMA’s enforcement powers

- Part

2 contains application and transitional provisions.

Background

The regulation of offline gambling in Australia has

traditionally been a matter for the states and territories as the Constitution

does not give the Federal Government power to legislate in this area. The

Federal Government is, however, able to regulate online gambling as section 51(v) of the Constitution, which gives it

power to make laws with respect to 'postal, telegraphic, telephonic, and other

like services', which means that it is able to legislate in the areas of communications

services.[3]

These include broadcasting, telecommunications and the Internet.

Gambling had been a consistent and prevalent pastime in

Australia since the arrival of the First Fleet, but it was not until the late

1990s that the Federal Government directed the Productivity Commission (PC or

the Commission) to undertake the first investigation of the overall economic

and social impact of gambling in Australia.[4]

Early

national analysis

Productivity

Commission inquiry

One of the references for the Commission was to investigate the

implications of new technologies (such as the Internet) and the effect these

technologies would have on traditional government controls on the gambling

industries.[5]

The PC’s November 1999 report noted the long-established

presence of gambling in Australian society, but added that ‘even by Australian

standards’, a recent growth in gambling industries had been ‘remarkable’ and

this growth had led to concern about the ‘downsides’ for society.[6]

That having been noted, the Commission concluded that Australians generally

enjoyed gambling, with over 80 per cent participating recently in some form of

gambling. At the same time, around two per cent of Australian adults could be

classified as problem gamblers, and one of the rationales for specific

regulation of the gambling industries stemmed from reducing the risks and costs

of problem gambling. Other rationales for gambling regulation were promoting

consumer protection and minimising the potential for criminal and unethical

activity.[7]

With regards to the gambling regulatory environment,

however, the PC argued that it was less than ideal as policies lacked coherence;

they were ‘complex, fragmented and often inconsistent’.[8]

It is interesting that similar assessments of gambling policies continue to be

made in 2016. The PC blamed inadequate policymaking processes and strong

incentives for governments to derive revenue from gambling industries for

deficiencies in in the gambling regulatory environment, and it is most likely

this is still the case with regards to the states and territories.[9]

The PC saw potential gains to many businesses and consumers

in the advent of new technologies, but it also believed those technologies posed

fresh challenges for regulation. It saw a role for the Federal Government in a

‘managed liberalisation’ of gambling online in co-ordinating a national

approach to regulation with the states and territories.[10]

Senate Select Committee Report

on Online Gambling

In 1999 the Senate Select Committee on Information

Technologies announced that it would specifically inquire into online gambling

in Australia. One of its terms of reference was to consider the need for

federal legislation.[11]

The Committee concluded that, while it appeared state and territory regulators intended

to regulate online gambling by applying uniform standards across jurisdictions,

in practice significant differences had emerged in the regulatory models they

were introducing to deal with online gambling.[12]

The Committee’s March 2000 report noted that evidence presented

to its inquiry suggested that the nature of the relationship between the states

and territories impeded the development of a national cooperative model for online

gambling and that a lack of collaboration undermined consumer protection. It recommended

that governments at all levels ‘work together to develop uniform and strict

regulatory controls on online gambling with a particular focus on consumer

protection ...’[13]

National

Office for the Information Economy (NOIE) report

On 7 July 2000, Senator Richard Alston, the Minister for

Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, announced that NOIE would

conduct a study into the feasibility and consequences of banning interactive

gambling.[14]

The NOIE report concluded that technically it was potentially

possible to implement a ban on interactive gambling based on Internet content

control but, importantly, NOIE added that no technical solution could be completely

effective in preventing every Australian from accessing interactive gambling

services.[15]

Enactment

of the IGA

In August 2000 the Government introduced an Interactive

Gambling (Moratorium) Bill 2000.[16]

There was enough opposition to the Bill that at first it failed to pass the

Parliament, but after the Government agreed to amendments to exempt interactive

services that were extensions of offline betting services (for example, betting

on horse races), the Interactive

Gambling (Moratorium) Act 2000 passed and was enacted in December 2000.

The statute imposed a 12-month moratorium on further development of the

interactive gambling industry by making it an offence for a person to provide

an interactive gambling service linked to Australia unless that person was

already providing the service when the moratorium commenced.[17]

In March 2001, Senator Alston announced that the Government

would introduce legislation to prohibit Australian gambling services from

providing online gambling to Australian residents.[18]

The Interactive Gambling Bill 2001 was introduced in April amid protest from

the Opposition and groups such as the Internet Industry Association.[19]

The IGA commenced 11 July 2001.

Interactive gambling services were defined in section 5 of

the IGA as those provided over the Internet or through broadcasting

services. Interactive services were not considered to be online telephone

betting, wagering on horse, harness or greyhound races, wagering on sporting

events or other events or contingencies, online lotteries, provided they are

not scratch lotteries or other instantaneous lotteries; gaming services

provided to customers in a public place (such as poker machines in a club or

casino) or services that have a designated broadcasting or data-casting link

(for example television shows that involve viewers voting in order to win

prizes).

Key functions of the IGA have been to:

- prohibit

interactive gambling services from being provided to customers in Australia

- prohibit

Australia-based interactive gambling services from being provided to customers in

designated countries

- establish

a complaints-based system to deal with internet gambling services where

prohibited Internet gambling content is available for access by customers in

Australia and

- prohibit

the advertising of interactive gambling services.[20]

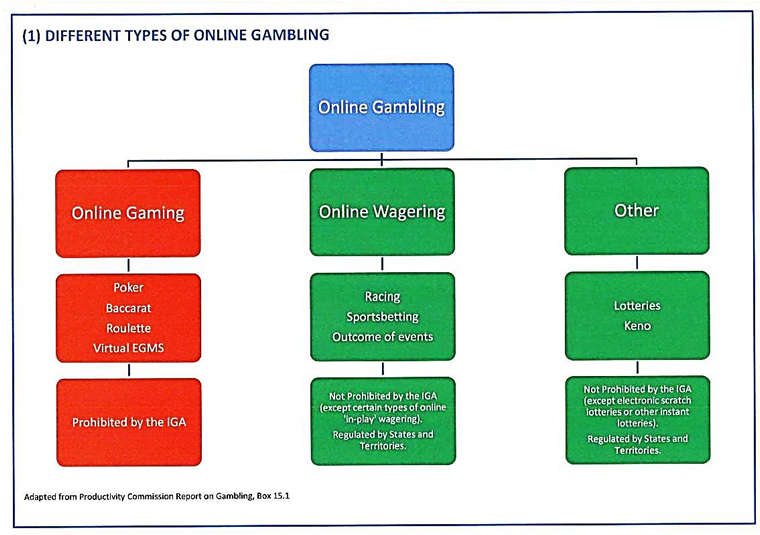

Figure 1 below shows the different types of online

gambling and indicates those prohibited by the IGA:

Figure 1: types

of online gambling

Source: Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform, Interactive

and online gambling and gambling advertising [and] Interactive Gambling and

Broadcasting Amendment (Online Transactions and Other Measures) Bill 2011, Second report, 8 December 2011, p. 8.[21]

Recent assessments

Since its passage, a number of critics have noted that the

IGA has done little to prevent the spread of interactive gambling, and

indeed, its weaknesses have contributed to the growth of this form of gambling.

In 2010 the PC pointed out that the prohibition in the IGA:

... perversely amounts to discriminatory deregulation, ensuring

that the Australian online gaming market is exclusively catered to by offshore

providers, who operate under a variety of regulatory regimes. This provides

inadequate protection to both recreational online gamblers, as well as online

gamblers who are at risk of developing a problem.[22]

In 2012 one critic summed up the views of many that the IGA:

... has proven to be a toothless tiger. International casino

websites completely ignored the ban and the threat of fines and continued to

operate at their leisure; in the ten years since the IGA was introduced, not a

single fine has been applied. The only impact was that no Australian company

could offer online casino gambling ... so all the money lost has gone offshore,

and Australian gamblers are taking an even bigger risk by using sites that do

not have to comply with Australian laws and regulations.[23]

2010—Productivity

Commission Inquiry report on gambling

In 2010, following an earlier request from the Government

for it to conduct an investigation into the gambling industry, the PC released

a report which updated its previous findings on aspects of gambling, including

its assessment of the implications of new technologies for traditional

government controls on gambling industries.[24]

In discussing the prohibition of online gaming under the IGA,

the PC was of the opinion that given the limited jurisdiction of Australian law

over overseas gambling suppliers the IGA had effectively prevented companies

located in Australia from selling online gaming services to Australians. The PC

was less sure of the effect of the IGA on Australian consumers, who can

legally access internationally based online gaming sites.[25]

That more evidence had emerged of the relative harm done by online gambling

since the earlier reports on gambling (noted above) had been published along

with doubts about the analysis underpinning the ban in the first place, suggested

a need for a re-evaluation of online gaming policy. The PC considered that the re-evaluation

should assess:

- the

relative harms and benefits of online gaming compared to venue-based gaming

- the

effectiveness of the prohibition, as well as any other additional costs it imposes

- the

scope for less restrictive regulation to minimise these harms whilst still allowing

some of the benefits of online gaming to be realised.[26]

In assessing the issues of harms and benefits the Commission

noted a number of positive and negative comparative effects. For example, for

non-problem gamblers, the use of credit cards for online gambling is unlikely

to cause financial harm, but for problem gamblers, it may have the opposite

effect. But at the same time, online gambling providers can usually monitor

spending patterns better than venue-based providers. The Commission was of the

view that risks associated with online gambling could be overstated, but there

was some ‘weak’ evidence to suggest gambling online may exacerbate already

hazardous behaviour of problem gamblers. Nevertheless, it concluded that careful

regulation of the online gambling industry was warranted.[27]

The PC estimated that it was probable the prohibition on

online gaming—in particular the prohibition on advertising online gaming—had

had some effect on demand, but the magnitude of that reduction was not clear

and ‘Australian consumption of online gaming has grown and will continue to do

so, making the prohibition less effective over time’.[28]

In terms of easing regulation, the Commission thought there

were two alternatives: the IGA could be strengthened to make it more

effective in dissuading Australians from online gaming or it could be amended

to realise the benefits of online gaming, while minimising its potential harms.[29]

Current debates about the regulation of online gambling continue to reflect

these views (see the section in this Digest on stakeholder comments).

The magnitude of the costs associated with strengthening the

IGA was such that the PC believed ‘the level of harm associated with

online gaming would need to be very high, and unavoidable through alternative

regulatory responses’ for this approach to be worthy of consideration. In

addition:

In the parallel physical gambling world, the Commission does

not consider that a ban on [electronic gambling machines such as poker machines]

is warranted despite evidence of considerable harm. Rather, the Commission has argued

for continued legal supply, but with more stringent consumer safety requirements.[30]

The Commission saw, instead, merits in an alternative

approach, that of:

... ‘managed liberalisation’, in which suppliers would be

licensed to provide online gaming to Australians, subject to strict conditions

about probity and harm prevention and minimisation. Managed liberalisation of

online gaming would better protect Australians from the risks of online problem

gambling, whilst still allowing recreational gamblers the freedom to choose an

enjoyable medium. It would also resolve the apparent paradox that the

Government allows Australian based firms to sell a product overseas that it

deems too dangerous for Australians themselves to consume.[31]

The PC saw some risks in the managed liberalism approach and

cautioned that its introduction should be gradual, thereby allowing a regulatory

agency, feasibly ACMA, to develop regulatory and investigative procedures for

online gambling as well as harm minimisation measures to protect consumers.

2010—Joint

Select Committee on Gambling Reform investigations

On 30 September 2010 the Parliament agreed

that a Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform (JSCGR) should be appointed to

inquire into and report on a number of gambling related issues including the Productivity

Commission report on gambling, gambling-related legislation introduced in the

Parliament and any other gambling-related matters.[32]

In the course of its existence the JSCGR produced a number

of reports, one of which is specifically relevant to matters relating to

interactive gambling raised in this Bill. This was the Inquiry into Interactive and online

gambling and the Interactive Gambling and Broadcasting Amendment (Online

Transactions and Other Measures) Bill 2011.

In this report the JCSGR noted the multiplicity of issues

posed by the various forms of and platforms for interactive gambling and agreed

with previous assessments that the key question to be addressed in dealing with

these is whether prohibition or liberalisation is a more effective approach. It

agreed with the PC that the IGA had been successful in limiting the provision

of interactive gambling services to Australians by Australian‑based

services, but less effective in limiting services from overseas providers.[33]

One difficulty acknowledged by the JSCGR with the IGA

was the enforcement process which was complaints‑based and subject to

reliance on the assistance of foreign authorities. The JSCGR discussed options

for dealing with this problem, for example, by blocking financial transactions with

known overseas gambling providers or blocking online gambling websites by Internet

Service Providers.[34]

It noted however, that the latter option, as the PC had previously concluded,

could be seen as ‘draconian’ and unlikely to be wholly successful and endorsed

work being undertaken by the AFP and the Department of Broadband, Communications

and the Digital Economy to improve enforcement mechanisms.[35]

The JSCGR was not in favour of setting up a system to monitor and block

financial transactions to deter people from accessing overseas-based interactive

gambling websites. It believed such a system:

... would never be completely effective, as those customers

most determined to circumvent the system would be likely to do so using other

methods. The committee also notes the difficulty in gaining cooperation from international

financial intermediaries such as PayPal to comply with such a system were it to

be introduced under Australian law.[36]

As the O’Farrell Review has found recently (see discussion

below), the JSCGR heard polarised accounts of the potential harm caused by in-play

(or in the run) betting online (in-play betting is permitted over the phone).

Industry provider Betchoice told the JSCGR that there was no evidence that

in-play betting online was riskier than other betting types.[37]

On the other hand, the lobby group FamilyVoice Australia considered that

in-play betting was likely to 'induce problem gamblers caught up in the

excitement of a match [to bet] inappropriate amounts on the spur of the moment'.[38]

The JSCGR did not support removal of the online in-play

betting ban. Given that in-play betting was permitted via the telephone and in

person, the Committee saw the restriction on the online format ‘as striking the

right balance’.[39]

2011—Department

of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy Review

On 27 May 2011, the Council of Australian Governments

(COAG) announced that the Government had decided to conduct a review of the IGA.[40]

The final report of this review, undertaken by the Department of Broadband,

Communications and the Digital Economy (DBCDE), was clear about what it saw as

the problem with the IGA:

The primary objective of the IGA is to reduce harm to

problem gamblers and to those at risk of becoming problem gamblers. The

evidence since the last review of the IGA suggests that it is making

only a very minor contribution to this objective. The IGA may in fact be

exacerbating the risk of harm because of the high level of usage by Australians

of prohibited services which may not have the same protections that Australian

licensed online gambling providers could be required to have.[41]

The DBCDE concluded that there could be as many as 2,200

online gambling providers offering services that may be in contravention of the

IGA and suggested that Australians may be losing nearly $1.0 billion a

year to online gambling service providers that are not licensed in Australia.[42]

In light of these findings the DBCDE called for a multi-pronged

approach to deal with the problem. Its fundamental recommendation was for a

national framework of harm minimisation and consumer protection measures for

all forms of permissible online gambling. Harm minimisation measures it

recommended included pre-commitment by gamblers, credit restrictions, the

provision of warning messages for gamblers and links to gambling helpline

services. All online gambling providers who did not apply the national harm

minimisation standard were to be prohibited.

The DBCDE also recommended providing incentives to

encourage online gambling providers to become licensed to operate and for

providers who chose not to become licensed to be prohibited from operating in

Australia. It called for targeted law enforcement and deterrence measures

against online gambling providers who continue to offer services to Australians

in contravention of the IGA.[43]

In addition, the DBCDE Review called for the legalisation

of online tournament poker and for changes to online in-play sports betting.

With regards to in-play betting, following from the JSCGR’s suggestion that

relaxing the ban on in-play betting for online providers may be worth

investigating and noting that there was support within the industry and sports

bodies for such an approach, the DBCDE proposed an alternative. It recommended

allowing simple in-play betting on line, (for example, betting on which team will

win a match) but continuing to restrict in-play betting on micro-events (for

example, betting on the outcome of the next ball in a cricket match) or

discrete contingencies within an event (for example, which player will score

the next goal in a football match).[44]

The PC’s 2010 report had recommended allowing regulated

online poker card playing (a subset of online gaming prohibited under the IGA)

‘subject to very strong harm minimisation and probity requirements as a better

means of protecting the many Australians who use such services from overseas

(that is, prohibited) websites’.[45]

The JSCGR had identified a range of arguments for and

against regulated access and the majority of that Committee supported the

prohibition. In his submission to the DBCDE’s interim report of its review Senator

Nick Xenophon, a member of the JSCGR, warned of possible parallels between the

opening up of access to electronic gaming machines in the early 1990s and

allowing regulated provision of online gaming.[46]

However, the chair of the JSCGR, Andrew Wilkie, supported the PC recommendation

for regulated access to online poker card playing. In recommending that a

five-year trial of online tournament poker should be instigated, the DBCDE

noted arguments from clinical psychologist Dr Sally Gainsbury who considered that

‘due to the fixed costs of tournament poker, this type of online poker appears

to have relatively low likelihood of leading to gambling problems’.[47]

Senator Xenophon criticised what he called the underlying reasoning

of the DBCDE Review declaring that simply because people ‘could already access

interactive gambling across the online border was not a good enough reason to

legalise it’ and argued that, once a type of gambling was sanctioned, the

implication was that it was safe. However, according to the Senator, ‘it’s a

downhill slide from there. Given how accessible and addictive online gambling

is, the risk is just too great’.[48]

The Government’s response to the DBCDE Review was to announce that it would

work with the various state and territory regulatory bodies to establish a

consistent national framework for harm minimisation and consumer protection

that would address all legal online gambling activities.[49]

2013—O’Farrell

Review

In the lead-up to the 2013 Federal election the Coalition also

criticised the approach suggested by the DBCDE and committed to investigating other

ways of strengthening the IGA.[50]

In fulfilling this commitment, in late 2015 the Government commissioned a

review of the impact of illegal offshore wagering to be undertaken by former

New South Wales Premier, Barry O’Farrell (the O’Farrell Review).

According to the O’Farrell Review, since 2012, online

gambling has grown significantly and this is consistent with an economy-wide

migration to online service delivery and significant investment in brand

awareness by online operators.[51]

The total amount spent on interactive gambling in Australia was US$2.0 billion in

2013 and US$2.2 billion in 2014. These figures included onshore and

illegal offshore gambling activities.[52]

In 2014, H2 Gambling Capital estimated that in excess of 20 per cent of

Australian expenditure on interactive wagering went to offshore providers.[53]

It noted the growth of illegal offshore markets and that wagering represents

the largest sector of the global internet gambling market.[54]

The O’Farrell Review noted that the major impacts of

offshore gambling activities have been assessed as:

- increased

risks to consumers as a consequence of reduced consumer protections

- lower

harm minimisation standards of some offshore sites

- a

potential increase in the threat to the integrity of sport and

- loss

of taxation revenue to the Government.[55]

The O’Farrell Review found that the main reasons consumers

wagered or gambled offshore were:

- better

product choice, specifically the availability of in-play wagering on sporting

events

- better

product value and

- the

ability to bet without the limits imposed by the domestic industry.[56]

According to the O’Farrell Review, if the Government seeks

to reduce the size of the illegal offshore wagering market it needs to address

these drivers of consumer behaviour.[57]

With regards to the IGA, in the course of its

investigations the O’Farrell Review was told of concerns that ‘the provision of

services by offshore operators is enabled by the wording of the Act, which

therefore increases the size of the offshore wagering market’.[58]

This concern was prompted by perceptions that the IGA was unclear about what

services are prohibited, it does not directly prohibit the provision of

wagering services by offshore providers, the current definitions within the IGA

make it difficult to enforce and the legislation does not make it illegal

to bet on offshore websites. In addition, enforcement of the IGA ‘is

difficult given that offshore providers operate beyond the reach of enforcement

agencies in Australia’.[59]

It stated what appears to have become a staple view when

considering online gambling issues:

... a nationally consistent and robust regulatory framework,

including the consistent application of harm minimisation and consumer

protection measures, is necessary before consideration is given to expanding

products available to consumers under the Act. In addition, the Review

considers it important that this nationally consistent regulation be enforced

in a manner that disrupts the access of offshore operators to the Australian

market.[60]

Recommendation 3 of the O’Farrell Review stated that until

a national framework is established and operating, consideration of additional

in-play betting products should be deferred and legislative steps taken to

respect the original intent of the IGA.[61]

Recommendation 17 of the Review called for amendments to

the IGA to:

- improve

and simplify the definition of prohibited activities

- extend

the ambit of enforcement to affiliates, agents and the like

- include

the use of name and shame lists published online to detail illegal sites and

their directors and principals and to include the use of other Commonwealth

instruments to disrupt travel to Australia by those named

- allow

ACMA, where appropriate, to notify in writing any relevant international

regulator in the jurisdiction where the site is licensed

- allow

ACMA to implement new (civil) penalties as proposed by the 2012 DBCDE Review and

- include

a provision that restricts an operator providing illegal services to Australian

consumers from obtaining a licence in any Australian jurisdiction for a

specified future time period (see all recommendations at Appendix A).[62]

The Government response to the O’Farrell Review noted

recommendation 3 and added that it did not intend to expand the Australian

gambling market by enabling online in-play betting as it was:

... of the view that the Australian online wagering agencies

offering ‘click-to-call’ type in-play betting services are breaching the

provisions and intent of the IGA. The Government will introduce legislation as

soon as possible to give effect to the intent of the IGA.[63]

With regards to recommendation 17 the Government agreed to

introduce legislative amendments to provide greater clarity around the legality

of services, strengthen the enforcement of the IGA and deliver improved

enforcement outcomes. It committed to introducing the mechanisms outlined in

the recommendation.[64]

On 25 November 2016 the Government reached agreement with

state and territory gambling ministers to establish a National Consumer

Protection Framework for online wagering. Ministers gave in-principle agreement

to key aspects of the Government’s response to the O’Farrell Review including

setting up a national self-exclusion register for online wagering, a voluntary

pre-commitment scheme for online wagering and prohibition of lines of credit

being offered by wagering providers.[65]

Committee

consideration

Selection

of Bills Committee

On 9 November 2016 the Selection of Bills Committee noted

that ‘contingent upon its introduction in the House of Representatives’ that

this Bill would be ‘referred immediately’ to the Environment and Communications

Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 30 November 2016. The reasons

stated for referral were:

- concerns

about enforcement of penalties on offshore gambling providers in problematic

jurisdictions and

- whether

the legislation will prevent offshore wagering in a meaningful way.[66]

Details of the inquiry are at the inquiry

homepage.[67]

At the time of writing this Bills Digest, 23 submissions had been received by

the Committee.

Senate Standing

Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills considered

the Bill but had no comment to make in relation to it.[68]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Senator Nick Xenophon has consistently called for tighter

gambling legislation. In his comments in the JSCGR Inquiry report on the

Interactive Gambling and Broadcasting Amendment (Online Transactions and Other

Measures) Bill in 2011, the Senator argued for the strengthening of the IGA

to improve its effectiveness.[69]

The Senator argued further that he supported additional measures to deter

people from using overseas websites to gamble, such as a government-maintained 'blacklist'

of merchant identification numbers to enable financial institutions to prohibit

transactions to certain vendors (this was discussed in the 2011 JSCGR Report).[70]

In separate comments in the JSCGR Report, Chair of the JSCGR, Independent Member

of Parliament Andrew Wilkie also considered that the possible introduction of a

blacklist should be investigated.[71]

In his submission to the O’Farrell Review, Senator

Xenophon expressed concern that its terms of reference were ‘too narrow and

ambiguous’ given the devastation caused to individuals and their families from

legal onshore online gambling sites authorised under the IGA. The

Senator considered that these legal sites should also be examined.[72]

Specifically in relation to the IGA Senator

Xenophon called for more power to be allocated to ACMA to make determinations

about prohibited gambling services and noted the problems ACMA had faced after

referring the licensed operator William Hill’s click to call betting practices

to the Australian Federal Police (AFP) (see Box 1).[73]

Box 1: click to call complaints

|

William Hill’s click to call product allows its

customers to place bets without having to make a traditional phone call. By

using an automated voice technology customers can place bets with the click

of their mouse, the only requirement being that the microphones on their

computers or mobile devices are switched on.

ACMA received a complaint about this practice in 2015

and referred the matter to the AFP. The AFP, however, declined to investigate

the complaint.

ACMA continued to be concerned that the click to call

practice falls under the prohibited provisions of the IGA and referred

the SportsBet operator’s Bet Live product to the AFP in July 2016. Both

William Hill and SportsBet maintained their products were wholly compliant

with the existing legislation.[74]

|

The Australian Greens have been consistent in calls for

the reform of gambling policy and legislation. For example, in April 2016, they

released a policy which would ban all gambling advertising in sport.[75]

To date, the Greens have made no specific comment on this Bill, however.

It has been reported that the Australian Labor Party

(ALP/Labor) is ‘unlikely’ to oppose the changes in this Bill although Labor’s

spokesperson on gambling, Julie Collins, has said the party would make a final

decision once it had seen the text of the Bill, but no further comment has been

made since the Bill was introduced.[76]

At the time of writing this Bills Digest it appears that

no other Parliamentarians have commented on this Bill.

Position of

major interest groups

All stakeholders appeared keen for changes to be made to

the IGA. One group wanted more liberalisation, primarily with regards to

relaxing the prohibition on in-play wagering and adopting what it labelled a

platform neutral regime. This group saw the lifting of restrictions as

delivering more protections for consumers and greater protections for sports

integrity. Another group of stakeholders supported a more cautious approach

arguing that in-play betting simply opened up more opportunities for corruption

in sport. Yet other comments argued for change, but did not specifically

address the in-play wagering debate.

For example, Clubs Australia called for the stronger enforcement

of the provisions within the IGA, appropriate resourcing of regulatory

and enforcement agencies and incorporation of greater standards of consumer

protection and harm minimisation. This organisation felt providing ACMA with

more power would improve legislative effectiveness. It listed allowing ACMA to issue

civil penalties, including infringement notices, take-down notices and the

ability to apply to the Federal Court if a gambling service provider fails to

comply with a notice as examples of such powers.[77]

Digital Industry Group Incorporated (DIGI—a group

consisting of Google, Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft and Yahoo!) considered the integrity

of racing and sports in Australia could be better maintained with stronger

enforcement of existing laws. These companies were firmly against any proposal

that would involve Internet filtering.[78]

The Communications Alliance agreed. It insisted that industry level website

blocking can be easily circumvented, and as such it is not a realistic and

practical alternative to the development of coherent and internationally

competitive industry policy.[79]

In-play

supporters

In its submission to the O’Farrell Review the Australian

Wagering Council argued that a new interactive gambling regime was needed to

respond to changes in the Australian wagering market which have occurred since

the introduction of the IGA.

According to the Wagering Council, consumers are not

gambling more, but they have changed their gambling preferences from onshore to

online. Yet increasingly popular forms of wagering, such as in-sport betting, are

not allowed online. As a result Australians wanting to wager in-play have been

obliged to use ‘traditional, less convenient means, or have recourse to

offshore wagering providers who offer these products’. The Wagering Council

argued this was detrimental to Australian licensed wagering providers who cannot

offer a product that is in demand.[80]

The Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) also called for a

more liberal approach to online gambling. The IGA was in need of reform

for the reason that it placed too many restrictions on gambling practices. As

for in-play betting, smartphones had made restrictions on this practice

obsolete; in-play betting offered consumers ‘more choice, greater participation

in spectator sport, and the opportunity to manage betting risk more

responsibility’.[81]

Bet365 also argued for the removal of the online in-play

sports-betting prohibition. The world’s largest online wagering company claimed

that illegal offshore wagering by Australians was ‘largely the direct result’

of the prohibition of in-play sports betting. Bet365 considered it was not

possible to minimise the incidence of problem gambling while so much of it is

conducted offshore, nor was it possible to control criminal elements. In

addition, it was to Australia’s economic advantage to reap the benefits of

relaxing the in-play prohibition.[82]

Sportsbet suggested an overall reform package of five

measures:

- make

it a legal requirement to be licensed in Australia in order to be permitted to

offer wagering services to Australian consumers

- adopt

a platform-neutral approach to in-play betting by removing the in-play

restriction

- strengthen

the deterrence measures deployed by ACMA

- increase

education and awareness among Australians of the dangers of transacting with

illegal offshore wagering operators

- introduce

mandatory responsible gambling initiatives:

- voluntary

pre-commitment

- reduced

time period for age verification of account holders

- mandatory

self-exclusion and national self-exclusion database

- wagering operators making appropriate

de-identified wagering information available to support research into wagering and appropriate public policy.[83]

Sportsbet pointed out that removing the in-play

restriction also has the support of Australia’s major sporting bodies citing

the Australian Football League, the National Rugby League and Cricket Australia

as well as the Coalition of Major Professional and Participation Sports

(COMPPS) who recognise that in-play betting is the product Australians are

using offshore, which has significant consequences for the integrity of their

codes.[84]

In-play opponents

Racing Australia’s submission to the O’Farrell Review

considered illegal offshore wagering ‘an unacceptable threat to the integrity

of racing and sport’. It was clearly in favour of changing the legislation to

make it legal for a wagering operator to provide wagering services to an

Australian customer where the wagering operator either holds a state or

territory wagering licence or approval to operate with respect to a particular sporting

event.[85]

Among other measures, Racing Australia supported amending

the IGA so ACMA could issue infringement notices to illegal gambling

services hosted in Australia and inform illegal offshore wagering operators of

their breach of Australian law. In addition, it considered the legislation

should mandate that financial institutions must block financial transactions

between Australian customers and illegal offshore wagering operators who have

been placed on an ACMA register of illegal offshore wagering operators. Legislation

should require Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block access by Australian

customers to illegal wagering sites that are operated by, or on behalf of, any

illegal offshore wagering operator who has been placed on the ACMA register of

illegal offshore wagering operators.[86]

But it did not support in-play betting. Racing Australia

considered that allowing this to occur would open up avenues for collusion

between jockeys and punters in order to enhance the value of a bet or to

increase the chances of a wager being successful. It considered:

... the Government of the day had good and cogent reasons for

prohibiting online in-play betting on sporting events. Those reasons are just

as valid today as they were when the legislation was drafted and it would be

negligent if they were repealed merely because illegal operators were offering

the in-play product. To do so could be seen as the Government transferring its

regulatory role to overseas operators.[87]

Canberra Greyhound Racing Club agreed that there should be

a national approach, that licensing of operators was essential and that the in-play

betting ban should continue. This stakeholder was frank in noting that, if the

ban was lifted, racing betters will move to online products and this will

exacerbate loss of revenue for the racing industry.[88]

In mounting a similar argument, the New South Wales

Trainers’ Association remarked:

Live betting or 'in the run betting' [that

is, in-play betting] for thoroughbred horse racing poses another threat to the

integrity of racing. Jockeys and Trainers are under enough pressure as it

is without having to deal with accusations brought about by from 'live in the

run betting'. It creates a difficult environment for racing and opens the door

for integrity issues which are obviously amplified with live sports that last

for much longer than 90 seconds. Furthermore industry research suggests that

the racing industry and venues that support it, could lose millions in revenue

due to migration. Evidence suggests that betting agencies are likely to

emphasise 'live in the run betting' products on sports such as Rugby League,

AFL, Soccer etc that run for over an hour, to generate intensified betting.

This could result in further losses to the racing industry where each

individual race is usually over in less than 2/3 minutes. Therefore 'live in

the run betting' provides a further risk for the integrity a racing and a reduction

in funds. [89]

The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation agreed with

Senator Xenophon that risks to Australians arising explicitly from offshore

online wagering should be seen in the context of the general issues that arise

in relation to all online wagering. It called for legislative changes including

maintaining and extending prohibitions on in-play betting as well as for a

nationally consistent approach to interactive gambling which dealt with issues

such as inducements to customers offered by gambling sites, advertising in

sports programs and requiring all providers to participate in a pre-commitment

scheme.[90]

Box 2: a media view

|

In anticipating the introduction of this Bill Bernard

Keane, writing in the online journal Crikey was in favour of liberalisation.

Keane stated:

The gambling industry is rightly unpopular, partly because

of its intrusive and annoying advertising techniques, but Australians enjoy

gambling, and the IGA has produced perverse and self-defeating

outcomes, particularly in driving gamblers to poor-quality offshore sites.

Rather than admit the logic that prohibition has failed, the government, in

true nanny-state style, is now looking to double down with attempts to compel

offshore regulators to obey Australians law and try to convince ISPs and

banks to co-operate in banning access to offshore sites.[91]

|

Comments to the Environment and Communications Committee

Inquiry into this Bill

In its submission to the Senate Environment and

Communications committee, eCommerce on-line Gaming Regulation and Assurance (eCOGRA),

a London-based organisation which administers self-regulation for members of

the on-line gambling industry, echoed what stakeholders had been saying

consistently about online gambling. eCOGRA argued that if the measures in this

Bill are to be effective then they need to be complemented by the introduction

of a national licensing scheme and national supervision of licence holders and

by national harm minimisation measures and consumer protection arrangements.[92]

eCOGRA contended that there were a number of weaknesses in

this Bill. Some of these were related to the introduction of the licensing

requirement. One problem for eCOGRA was that licences will be state or territory

based and as such, because state and territory laws are inconsistent, licence

conditions will inevitably be inconsistent. So the list of prohibited,

unlicensed gambling services proposed in the Bill will also vary according to

the criteria used for licensing in each state and territory.[93]

In addition, consumer protection in the area of credit or deferred settlement

will also be subject to state laws and therefore not implemented uniformly or

consistently.

In criticising the online in-play betting prohibition,

eCOGRA observed that while the rationale for allowing telephone in-play betting

is that contact with an operator is likely to inhibit betting more than through

a computer terminal, common sense ‘would indicate that there is little

commercial interest in telephone operators for major domestic gambling service

providers dissuading potential clients from placing in-play bets’.[94]

According to the eCOGRA assessment, a focus in the Bill on

prohibition and enforcement will also mean:

... harm minimisation measures utilised worldwide are not

satisfactorily addressed. These include managing of deposits limits, control of

deposit frequency, enforced break periods, reality checks and voluntary session

suspension ...[95]

Finally, eCOGRA believed the Bill’s enforcement powers will

continue to prove ineffective because of the difficulty in enforcing judgments

outside Australia.[96]

The Australian Psychological Society made little comment on

the actual provisions of this Bill but called the proposed measure to prohibit

‘click to call’ in-play betting services by tightening the definition of a telephone

betting service ‘a good example of disruption of ready accessibility as a harm

minimisation measure’.[97]

The Synod of Victoria and Tasmania, Uniting Church in

Australia, and Uniting Communities submission to the Senate Committee was

supportive of the proposed measures in this Bill, particularly the proposals to

prohibit click to call betting.[98]

Bet365 iterated its earlier call to the O’Farrell Review for

removal of the online in-play sports betting prohibition and registered its

opposition to the proposed measures in the Bill which relate to place-based

betting services. The proposal would allow for electronic terminals to continue

to operate in places such as hotels, clubs or casinos where providers are licensed

under state or territory law to provide such services. Bet365 sees no

justification for allowing this exemption and considers it:

... will specifically allow for a very rapid expansion –

especially by TAB outlets – of tablet/iPad-style devices with inplay sports-betting

functionality into many more locations, including public locations such as Martin

Place (Sydney), Federation Square (Melbourne) and major sporting grounds such

as the Melbourne Cricket Ground.[99]

The Crownbet and Betfair submission also raised the issue of

the place-based betting proposals, remarking that the government’s arguments

about the interaction factor which makes in-play telephone betting acceptable

are undermined if hotels, clubs and the like are allowed:

... to offer in-play betting services that are identical, in

terms of the high speed of bet placement, as an online wagering service. There

is further no interaction required whatsoever with an operator, and no human

supervision, unlike electronic betting terminals, which are permitted only in

designated wagering areas and required to be staffed at all times.

This proposed provision therefore undermines the primary

reasons that the Government has not sought to prohibit retail or telephone

in-play wagering. This is an anomaly that undermines the principles of platform

neutrality and the perceived protections that the Government considers

consumers receive when engaging in retail or telephone based wagering.[100]

Crownbet/Betfair express concern that the sporting event

proposal in this Bill effectively prevents betting from taking place for events

which take place over a number of days once the first day of those events has

commenced. They argue it is ‘nonsensical’ to prohibit, for example, wagering

prior to the various days’ play in a golf tournament. They suggest that this

anomaly could, however, be addressed by amending this provision to introduce the

concept of a ‘scheduled extended play break’ which could be defined ‘to include

any hiatus in play which extends overnight, or for more than a prescribed

period’.[101]

Financial

implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, it is not

expected that this Bill will have ‘any significant impact on Commonwealth

expenditure or revenue’.[102]

There will be some cost for ACMA in establishing and administering the proposed

new enforcement processes. The Explanatory Memorandum estimates these will be a

one-off capital cost of $500,000 and ongoing costs of $2.0 million per annum,

but it stresses these costings are estimates only.[103]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary

Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth),

the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and

freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in

section 3 of that Act. According to the assessment in the Explanatory

Memorandum to the Bill some of its provisions may engage human rights as

defined in Articles 14 and 17 of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[104]

For example, item 39 proposes that proposed section

15AA of the Bill would create new criminal and civil penalties for those

who intentionally provide a regulated interactive gambling which has an

Australian link and for which they do not hold a licence to authorise operation

of that service in Australia. The Bill provides for an exception to this rule (subsection15AA(5)),

where a person is not aware that a service has an Australian customer link and

could not ‘with reasonable diligence’ have ascertained that the service has

such a link. At the same time, proposed subsection 15AA(5) notes that the

defendant needs to prove that he or she had no knowledge of the Australian

link. This may be considered to limit the rights in Article 14(2) of the Convention,

which states that persons charged with criminal offences have the right to be

presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Further, items 3 and 4 of the Bill engage the

right to protection against arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy

under Article 17(1) of the Convention. These items amend the list of

authorities in the ACMA Act to whom information about a prohibited or

registered interactive gambling service may be disclosed.[105]

These issues are discussed comprehensively in the

Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill. The Government considers that the Bill is

compatible with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights because

any limitations it imposes on human rights ‘are reasonable, necessary and

proportionate’.[106]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considered

that the Bill did not raise human rights concerns.[107]

Key issues

and provisions

This section does not discuss all provisions

in this Bill. For a detailed analysis of all provisions, see the Explanatory

Memorandum.

ACMA Act

Items 1–5 of the

Bill amend the ACMA Act which, amongst other things, establishes ACMA

and sets out its functions and powers.[108]

Currently Part 7A of the ACMA Act sets out the circumstances in which authorised

disclosure information may be disclosed and to whom it may be

disclosed.[109]

Item 1 of the Bill amends the definition of authorised disclosure

information in section 3 of the ACMA Act to include information

gathered under the complaints handling systems contained in Parts 3, 4 and 5 of

the IGA.

Within Part 7A, section 59D provides for the

disclosure of authorised disclosure information to certain

authorities. Items 3 and 4 amend subsection 59D(1) of the ACMA Act to expand

the list of authorities to whom authorised disclosure information

about gambling services may be provided to include:

- the Secretary of the Department administered by the Minister who

administers the Migration

Act 1958 or employees in the

Department whose duties relate to that Act

- an authority of a foreign country responsible for regulating matters

relating to the provisions of gambling services (note: item 2 will

insert a definition foreign country).

Item 5 inserts proposed

subsection 59(1A), to ensure that only information that relates to a

prohibited interactive gambling service or a regulated interactive gambling

service (and not any other information that ACMA may collect) may be disclosed

to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection or foreign regulators.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to

the Bill, these amendments:

... are intended to promote effective enforcement

of the IGA by enabling the ACMA to notify international regulators and the

Department of Immigration and Border Protection of information relating to

prohibited or regulated interactive gambling services.[110]

IGA

Items 6 to 143

amend the IGA.

New definitions

The Bill inserts a number of new and

important definitions into the IGA.

Prohibited interactive gambling service

Currently the IGA identifies various

types of interactive gambling service and creates the offence of providing an

interactive gambling service to customers in Australia. Item 8 of the

Bill repeals the definition of interactive gambling service. Item 9 of

the Bill inserts the definition of prohibited interactive gambling

service. Items 19–22 of the Bill operate so that references in

the IGA to an interactive gambling service become references to a

prohibited interactive gambling service; further, these items signpost the

introduction of civil penalty provisions which will be in addition to existing

criminal penalty provisions.

Regulated interactive gambling service

Item 28 inserts proposed section 8E into the

IGA to define the term regulated interactive gambling service.

It is proposed that a regulated interactive gambling service will be defined as:

- a

telephone betting service — being a gambling service that is provided ‘on the

basis that dealings with customers are wholly by way of voice calls made using

a carriage service’ (proposed subsection 8AA(1) at item 25). A

voice call is defined in proposed subsection 8AA(3) as one that consists

wholly of a spoken conversation between individuals or, in the case of

customers with a disability, a call that is equivalent. Proposed subsection

8AA(8) provides that, despite subsection 8AA(1), a gambling service that

provides that certain information, such as the selection of a bet or the

nomination of a bet amount, can be provided by a customer otherwise than by way

of a voice call, will not be a telephone betting service for the purposes of

the IGA. In its submission to the current inquiry into this Bill Tabcorp

sought clarification of whether the list in proposed subsection 8AA(8) is

intended to include customer account information (such that customers would need

to provide identifying information by voice in order for a service to be

considered to be a telephone betting service)[111]

- an

excluded wagering service — being a service which relates to betting on horse,

harness or greyhound racing. In addition, an excluded wagering service is one

that relates to betting on sporting events or other events or contingencies — provided

that the service is not an in-play betting service (proposed section 8A at

item 26). Consistent with this section, proposed section 10A (at

item 32) impacts on how the term sporting event is

defined for the purposes of the IGA. The section will empower the

Minister to declare if a ‘specified thing’ is, or is not, a sporting event. Proposed

subsection 10A(4) provides examples of ‘things’ that may be specified in a

Ministerial determination as a sporting event (or specified as not being a

sporting event). They include a match, a race, a tournament or a round.

Further, proposed section 10B operates so that a gambling service is an in‑play

betting service to the extent to which it relates to betting on the

outcome of a sporting event or on a contingency that may or may not happen in

the course of a sporting event, where the bets are placed, made, received or

accepted after the beginning of the event. Free TV Australia has commented that

this provision which ‘leaves a core regulatory obligation to be determined by

the Minister, creates significant uncertainty regarding the impact of the Bill

and exposes regulated parties to potentially significant regulatory change on

short notice’. Free TV considers that the Bill should be amended to include a

definition of sporting event or alternatively, the proposed legislative

instrument should accompany the Bill’[112]

- an

excluded gaming service — being a service for the conduct of certain games[113]

provided to customers at a particular place, using electronic equipment which

is available to all customers at that place (proposed subsection 8B at

item 27)

- a

place-based betting service — being a service for the placing, making,

receiving or acceptance of bets, or which introduces people wishing to make bets

with people willing to accept bets, which is provided to customers at a

particular place using electronic equipment which is available to all customers

at that place (proposed section 8BA at item 27). Under proposed

paragraph 8BA(1)(c) the provider of the service needs to hold a licence

under state or territory law to authorise the service to be provided. Tabcorp

has suggested that this proposed section could be made clearer by

stating that customers must be at the place at the time the service is provided

and that the licence required under proposed paragraph 8BA(1)(c) be a licence

issued by the state or territory in which the service is provided [114]

- a

service that has a designated broadcasting link under existing section 8C

- a

service that has a designated datacasting link under existing section 8C

- an

excluded lottery service under existing section 8D

- an

exempt service.

These services must be provided in the course of carrying

on a business and be delivered by either an Internet carriage service or any

other listed carriage service, a broadcasting service, any other content

service or by a datacasting service (proposed paragraph 8E(1)(j)).

Proposed paragraph 8E(1)(k) adds that in the case

of an exempt service, a Ministerial determination under proposed subsection

8E(2) must be in force in relation to the service.[115]

Designated

interactive gambling service

Item 7 of the Bill inserts the term designated

interactive gambling service, being either a prohibited interactive

gambling service or an unlicensed regulated interactive gambling service, into

section 4 of the IGA.

Prohibited

internet gambling content

Proposed section 8F of the IGA (at item

28) provides that internet content is prohibited internet gambling

content if end-users in Australia can access the internet content and an

ordinary reasonable person would conclude that the sole or primary purpose of that

internet content is to enable a person to be a customer of either one or more

illegal interactive gambling services or one or more unlicensed regulated interactive

gambling services, or both.

New offence and increased penalties

Item 33 repeals and replaces the heading of Part 2

of the IGA — Designated interactive gambling services not to be

provided to customers in Australia — to reflect its content more accurately.

Currently, section 15 of the IGA (which is the only

provision in Part 2) states that a person commits an offence if the person

intentionally provides an interactive gambling service which has an Australian-customer

link—the maximum penalty for this is 2,000 penalty units (being equivalent to

$360,000).

Items 35 and 35A operate to increase the existing

maximum criminal penalty for intentionally providing a prohibited interactive

gambling service with an Australian customer link to 5,000 penalty units

(being equivalent to $900,000).

Item 39 of the Bill inserts proposed section

15AA which provides that a person commits a criminal offence if the person

intentionally provides a regulated interactive gambling service which has an

Australian customer link and the person does not hold a licence under a law of

the state or territory that authorises the provision of that kind of service.

The maximum penalty is 5,000 penalty units, being equivalent to $900,000.

However, it is a defence if the person did not know and could not, with

reasonable diligence, have ascertained that the service had an Australian

customer link.[116]

The defendant will bear the evidential burden of establishing this.

The new civil penalty provisions are contained in:

- proposed

subsections 15(2A) and (2B) which operate so that a person must not provide

a prohibited interactive gambling service that has an Australian-customer link.

The maximum civil penalty is 7,500 penalty units, being equivalent to

$1,350,000. Where a person contravenes the prohibition he, or she, commits a

separate contravention in respect of each day during which the contravention

occurs

- proposed

subsections 15AA(3) and (4) which operate so that a person must not provide

a regulated interactive gambling service if the service has an Australian

customer link and the person does not hold a licence under a law of the state

or territory that authorises the provision of that kind of service. The maximum

civil penalty is 7,500 penalty units, being equivalent to $1,350,000. Where a

person contravenes the prohibition he, or she, commits a separate contravention

in respect of each day during which the contravention occurs and

- proposed

subsections 15A(2A) and (2B) which operate so that a person must not

provide a prohibited interactive gambling service that has a designated

country-customer link. The maximum civil penalty is 7,500 penalty units. Where

a person contravenes the prohibition he, or she, commits a separate contravention

in respect of each day during which the contravention occurs.

Key

issue—penalty amounts

Under the current IGA, offences which arise from contravening

conduct are criminal offences. The standard of proof in a criminal case is

‘beyond a reasonable doubt’. However, the offence will not be committed if the

defendant establishes that he, or she, did not know and could not, with

reasonable diligence, have ascertained that the service had an

Australian-customer-link.[117]

The existing offences, if proven, allow for financial penalties to be paid

rather than imposing a term of imprisonment.

The Bill provides for existing offence provisions to also

be civil penalty provisions so that ACMA can apply to the court for a civil

penalty order against a person who has contravened a civil penalty provision.[118]

In addition, it provides ACMA with powers to issue infringement notices,[119]

issue formal warnings[120]

and to apply to the court for injunctions, including injunctions to undertake,

or to cease from undertaking, certain actions.[121]

Civil penalties, infringement notices and injunctions will be enforced under

the Regulatory

Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014, which contains a standard suite

of provisions containing investigative, compliance monitoring and enforcement

powers which can be applied to individual pieces of Commonwealth regulatory

legislation.[122]

Essentially, the Bill (and the current Act) prohibits

certain conduct. That conduct may give rise to a criminal offence as well as

being a civil penalty provision. There appears to be no

difference in the conduct involved or in the rationale of the provisions—the

differences are the increased penalties to which a person is subject in civil

penalty proceedings, the lesser standard of proof that is required, and

differing procedural requirements and guarantees. The choice of which type of

proceedings takes place appears to be at the discretion of ACMA.

The Bill provides for ACMA to apply to a

civil court for an order that a person pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary

penalty. The maximum pecuniary penalty is 50 per cent greater than the amount

payable as a fine were the conduct prosecuted as a criminal offence. According

to the Explanatory Memorandum:

To reduce the adverse effects [of gambling] the

penalty amounts for contraventions of the IGA need to be high, in particular

for major offences including the provision of prohibited interactive gambling

services and unlicensed regulated interactive gambling services, to deter

offshore global entities from providing services to the Australian market.[123]

In addition, whilst the civil penalties deal with the same

conduct, ‘the penalty for the civil offence is higher, given that the criminal

offence also carries with it the stigma of a criminal conviction’.[124]

Items 51 to 66 amend Part 3 of the IGA, to

set out the new processes under which persons may complain to ACMA about

interactive gambling services that should not be provided to Australian

customers, or by Australian companies to consumers in designated countries. Item

53 proposes to increase ACMA’s powers of investigation in this area. It

allows for ACMA ‘to handle the entire complaints and investigation process from

the receipt of a complaint to enforcement’.[125]

Item 82 of the Bill renames the heading for Part 7A

of the IGA to Prohibition of advertising of designated interactive

gambling services. Within Part 7A, section 61BA as amended by items 87

to 91 will define a designated interactive gambling

service advertisement as any writing, still or moving picture, sign,

symbol or other visual image, or any audible message, or any combination of two

or more of those things, that gives publicity to, or otherwise promotes or is

intended to promote:

a) a

designated interactive gambling service or

b) designated

interactive gambling services in general or

c) the

whole or part of a trade mark in respect of a designated interactive gambling

service or

d) a

domain name or URL that relates to a designated interactive gambling service;

or

e) any

words that are closely associated with a designated interactive gambling

service (whether also closely associated with other kinds of services or

products).

Items 92–98, 100–104 and 107–114 of

the Bill then amend references to an interactive gambling service

advertisement to a reference to a designated interactive gambling

service advertisement. The effect of the amendments is to extend the

prohibition on advertising in the IGA to include the types of services

that are unlicensed regulated interactive gambling services. Currently

section 61DA of the IGA provides for two criminal offences:

- first,

a person commits an offence if the person broadcasts or datacasts an

interactive gambling service advertisement in Australia and the broadcast or

datacast is not permitted by section 61DB (which permits accidental or

incidental broadcast or datacast) or by section 61DC (which permits broadcast

or datacast of advertisements during flights of aircraft)[126]

- second,

a person commits an offence if the person authorises or causes such a broadcast

or datacast.[127]

In either case, the maximum penalty for contravention is 120 penalty units,

being equivalent to $21,600.

Item 117 of the Bill updates the reference to a

gambling service advertisement to a reference to a designated interactive

gambling service advertisement. Items 118 and 121 of the Bill

insert proposed subsections 61DA(1A) and (3) respectively into the IGA

to create civil penalty provisions that parallel the existing criminal offences

in that section. Where the civil penalty provisions are contravened the maximum

penalty is 180 penalty units being equivalent to $32,400.

Currently section 61EA of the IGA provides for two

criminal offences:

- first,

a person commits an offence if the person publishes an interactive gambling

service advertisement in Australia and the publication is not permitted by section

61EB (which permits the publication of periodicals distributed outside

Australia); section 61ED (which permits accidental or incidental publication);

section 61EE (which permits publication by person not receiving any benefit);

and section 61EF (which permits publication of advertisements during flights of

aircraft)[128]

- second,

a person commits an offence if the person authorises or causes such an

advertisement to be published in Australia.[129]

In either case, the penalty for contravention is 120 penalty units, being

equivalent to $21,600.

Item 126 of the Bill updates the reference from an

interactive gambling service advertisement to a reference to a designated

interactive gambling service advertisement. Items 127 and 129 of

the Bill insert proposed subsections 61EA(1A) and (2A) respectively into

the IGA to create civil penalty provisions that parallel the existing

criminal offences in that section. Where the civil penalty provisions are

contravened the maximum penalty is 180 penalty units being equivalent to

$32,400.

Appendix A: Recommendations of the O’Farrell Review

Recommendation 1: Commonwealth, State and Territory governments

should recommit to Gambling Research Australia to ensure that research funds