Bills Digest no. 39, 2016–17

PDF version [835KB]

Michael Klapdor

Social Policy Section

18 November 2016

This Bills Digest updates an earlier

version dated 20 April 2016.

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

List of abbreviations

History of the Bill

Purpose of the Bill

Structure of the Bill and the Bills

Digest

Background

Early childhood education and care in

Australia

Approvals

Provider and service approvals

Approval for Child Care Benefit

Australian Government funding for early

childhood education and care

Table 1: Key components of Australian

Government child expenditure, budget estimates, $’000

Child Care Benefit

Income test and payment rates

Grandparent Child Care Benefit

Special Child Care Benefit

Child Care Rebate

Jobs, Education and Training Child

Care Fee Assistance

Funding for providers and quality

support

Jobs for Families Package

Revised Jobs for Families package

Table 2: Revised Child Care Subsidy

income test

Chart 1: Rate of Child Care Subsidy

by family income

Impact of the revised package

Table 3: Families expected to receive

a lower subsidy rate by income band, 2017–18

Table 4: ANU Centre for Social

Research and Methods modelling of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ from proposed Jobs for

Families policy—families

Committee consideration

Previous consideration

Senate Education and Employment

Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Consideration of the 2016 Bill

Senate Education and Employment

Legislation Committee

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

Policy position of non-government

parties/independents

Australian Labor Party

Australian Greens

Nick Xenophon Team

Position of major interest groups

Financial implications

Statement of Compatibility with Human

Rights

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

Key issues and provisions

Table 5: Key differences between the

2015 and 2016 versions of the Jobs for Families Package Child Care Bill

Concluding comments

Date introduced: 1

September 2016

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Education

and Training

Commencement: Schedules

1 and 2 on 2 July 2018; Part 1 of Schedule 3 and Schedule 4 on the day

after Royal Assent; and Part 2 of Schedule 3 on 1 July 2017.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent,

they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation

website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at November 2016.

The Bills Digest at a glance

The Family Assistance Legislation

Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016 (the Bill) provides

for the key legislative changes required to implement the Government’s Jobs for

Families child care reform package. The package was a key 2015–16 Budget

measure and is based on recommendations from the Productivity Commission’s

inquiry into childcare and early childhood learning. The package, when

announced, included an additional $3.5 billion in expenditure on child care

assistance over five years.

The Bill introduces:

- A new child care fee assistance payment, the Child Care Subsidy

(CCS), replacing two current payments: Child Care Benefit (CCB) and Child Care

Rebate (CCR).

- A new supplementary payment, the Additional Child Care Subsidy

(ACCS), which provides additional financial assistance for children at risk of

abuse or neglect, families experiencing temporary financial hardship, families

transitioning to work from income support, grandparent carers on income

support, and low income families in certain circumstances. The ACCS partly

replaces a number of current payments including Special Child Care Benefit,

Grandparent Child Care Benefit and the Jobs, Education and Training Child Care

Fee Assistance payment.

- An enhanced compliance framework.

The new payments are to commence from July 2018, while

aspects of the new compliance framework will be introduced from Royal Assent.

In 2014–15, the Australian and state and territory

governments spent close to $9 billion on early childhood education and care

(ECEC) with the main expenditure item being fee assistance payments provided to

parents using approved childcare services. In the September quarter of 2015,

there were 1,269,190 children and 859,380 families using approved care. The

Productivity Commission found that the current fee assistance system is

complex, creates work disincentives, is poorly targeted and was creating fiscal

pressure for government.

The new CCS payment provides a subsidy rate based on a

percentage of the actual fee or an hourly benchmark price (whichever is lower).

The benchmark price is different for each service type. The percentage covered

is determined by family income with a subsidy rate of 85 per cent of the

benchmark price or actual fee for families with incomes at or below $65,710 per

annum. This rate tapers by one percentage point for every $3,000 in income over

this threshold to 50 per cent for family incomes at $170,710. A flat subsidy

rate of 50 per cent applies for family incomes between $170,710 and $250,000

and then tapers for incomes over $250,000 until it reaches the base rate of 20

per cent of the benchmark price (for incomes at or above $340,000 per annum). Families

with incomes over $185,000 will have their CCS entitlement capped at $10,000

per child per year.

A three-part activity test determines the number of hours

that can be subsidised: 8–16 hours per fortnight of approved activities

provides up to 36 hours of CCS per fortnight; 17–48 hours provides up to 72 hours

of CCS; more than 49 hours of approved activities provides up to 100 hours of

CCS. For couple families, the partner with the lower number of hours of

activity determines the CCS entitlement. Approved activities include work,

training, study or certain other recognised activities such as volunteering, as

well as participation requirements for income support payments. Families with

incomes of up to $65,000, who do not meet the activity test, will be eligible

to receive up to 24 hours of CCS per fortnight under a separate program known

as the Child Care Safety Net.

The Child Care Safety Net will replace existing funding

programs for service providers and also includes the ACCS. The ACCS will

provide a top-up payment to the CCS for disadvantaged and vulnerable families.

The Government estimates that around 815,600 families will

receive a higher level of fee assistance under the changes compared to the

current funding model; around 140,500 families will receive around the same

level of assistance and around 183,900 families will receive a lower level of

assistance. Alternative modelling by the ANU’s Centre for Social Research and

Methods estimated 582,000 families will be better off, around 330,000 families

will be worse off and 126,000 families will receive around the same level of

subsidy.

Providers, academics and interest groups are concerned

that the activity test is too complex and will exclude many children from ECEC.

There are also concerns at the new administrative requirements for providing

assistance to children at risk of abuse and neglect. The design of the CCS

payment may also lead to a decline in the real value of assistance provided to

families over time, and significant child care fee increases will need to be

borne by families without additional assistance from government.

List of abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| ABS |

Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| ACA |

Australian Childcare Alliance |

| ACCS |

Additional Child Care Subsidy |

| ACECQA |

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority |

| ANU |

Australian National University |

| CCB |

Child Care Benefit |

| CCR |

Child Care Rebate |

| CCS |

Child Care Subsidy |

| CPI |

Consumer Price Index |

| ECA |

Early Childhood Australia |

| ECEC |

Early childhood education and care |

| FA Act |

A New Tax System (Family Assistance) Act 1999 |

| FA Admin Act |

A New Tax System (Family Assistance) (Administration)

Act 1999 |

| FDC |

Family day care |

| GST |

Goods and Services Tax |

| IHC |

In-home care |

| JETCCFA |

Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance |

| LDC |

Long day care |

| National Law |

Education and Care Services National Law |

| National Regulations |

Education and Care Services National Regulations |

| NQF |

National Quality Framework |

| OSHC |

Outside school-hours care |

| PC |

Productivity Commission |

| SCCB |

Special Child Care Benefit |

History of

the Bill

A version of this Bill was introduced into the 44th

Parliament on 2 December 2015.[1]

The previous Bill was not debated following its introduction in the House of

Representatives and lapsed at prorogation on 15 April 2016. While the main

provisions in the new Bill are the same as the previous version, a number of

notable changes have been made. These are discussed below.

In the 2016–17 Budget the Government announced that it

would delay the commencement of the measures by a year: from July 2017 until

July 2018.[2]

The reason given for the delay was the Senate not passing savings from the

Family Tax Benefit program that the Government has linked to funding for the

Jobs for Families Child Care Package.[3]

These savings measures have being reintroduced in the Social Services Legislation

Amendment (Family Payments Structural Reform and Participation Measures) Bill

2016.[4]

Purpose of

the Bill

The purpose of the Family Assistance Legislation Amendment

(Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Bill 2016 (the Bill) is to amend the A

New Tax System (Family Assistance) Act 1999 (the FA Act),[5]

the A New Tax System (Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 (the FA

Admin Act),[6]

the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999,[7]

the Early Years Quality Fund Special Account Act 2013,[8]

the Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986[9]

and the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997[10],

to introduce the following elements of the Government’s Jobs for Families child

care package:

- a

new child care fee assistance payment, the Child Care Subsidy (CCS), replacing

two current payments: Child Care Benefit (CCB) and Child Care Rebate (CCR)

- a

new supplementary payment, the Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS), which

provides additional financial assistance for children at risk of abuse or

neglect, families experiencing temporary financial hardship, families

transitioning to work from income support, grandparent carers on income

support, and low income families in certain circumstances. The ACCS partly

replaces a number of current payments including Special Child Care Benefit,

Grandparent Child Care Benefit and the Jobs, Education and Training Child Care

Fee Assistance payment

- an

enhanced compliance framework.

The new payments are to commence from July 2018, while some

aspects of the new compliance framework will be introduced from Royal Assent.

Structure of the Bill and the Bills Digest

The Bill comprises four Schedules:

- Schedule

1 provides for the main amendments to family assistance law to provide for the

introduction of the CCS and ACCS to replace the current system of child care

fee assistance payments

- Schedule

2 makes consequential amendments to a number of pieces of legislation,

primarily tax law, to reflect the new child care payment system and terminology

around types of care

- Schedule

3 makes amendments to: allow determinations made by the Minister in relation to

immunisation requirements to incorporate matters set out in other written

instruments; provide for the Goods and Services Tax (GST) treatment of certain

child care services (allowing for the Minister for Education and Training to

determine that certain kinds of child care are GST-free); and provide for the

approval of child care services under family assistance law during the

transition period to the new child care payment system, and for the cessation

of enrolment advances

- Schedule

4 provides for application, transitional and savings provisions relating to the

transition from the current child care payment system to the new system. The

Schedule includes a provision giving broad powers to the Minister for Education

and Training to make rules, including the power to modify principal

legislation, ostensibly to ensure a smooth transition to the new child care

payment system.

The Bills Digest for the previous Bill provided background

to the Jobs for Families Package (including an overview of child care in

Australia) and a detailed analysis of the main provisions.[11]

This Bills Digest will describe the key differences

between the two Bills, provide details of any committee inquiries and reports,

provide updated information on the views of non-government parties or members,

and any new comments from key stakeholders. This Bills Digest will also provide

a brief description of the key changes but the previous Bills Digest should be

referred to for more detailed discussion of the relevant issues.

Background

For full background on the child care system in Australia

and Australian Government funding for child care, see the Background section of

the Bills Digest for the previous Bill.[12]

Early

childhood education and care in Australia

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates that

there were 3.8 million children aged 0–12 in Australia as at June 2014.[13]

Almost half (1.8 million) received some form of child care. Nearly a quarter

(919,400) attended formal care and 1.3 million attended informal care—such as

care by grandparents or other relatives.[14]

Around 327,800 children usually attended both formal and informal child care.

Formal care is care provided by the early childhood education and care (ECEC)

sector and includes:

- long

day care (LDC)—a centre based form of ECEC catering for children aged zero to

six years

- family

day care (FDC)—a flexible form of ECEC (all-day, part-time, casual, overnight,

before/after school and school holiday care) provided in the home of carers

(referred to within the sector as educators)

- in-home

care (IHC)—a flexible form of ECEC provided to eligible children by an educator

in the family home

- outside

school hours care (OSHC)—a centre-based form of ECEC for primary school aged

children and available before and after school (7.30am–9.00am, 3.00pm–6.00pm),

during school holidays and on pupil‑free days and

- occasional

care—a flexible form of centre-based ECEC that can be accessed on a regular

basis (like LDC) or as the need arises. For example, where parents have

irregular or unpredictable work hours.[15]

The ECEC sector also includes preschool services—generally

defined as structured, play-based learning programs delivered by degree

qualified teachers to children in the year or two before they commence full

time schooling.[16]

While some LDC and OSHC services also deliver preschool programs, preschool is

defined separately from child care and different governance and funding

arrangements apply to preschool and child care services.

According to the ABS, LDC is the most attended of all

formal child care services, with 13.5 per cent of all children aged 0–12

usually attending an LDC service.[17]

Around 7.8 per cent of children attended OSHC services and 2.5 per cent

usually attended an FDC service.[18]

For younger age-groups, the percentage of children attending formal services is

much higher: 41.8 per cent of two year-olds (129,300) and 49.3 per cent of

three year-olds (146,200) usually attended LDC services as at June 2014.[19]

According to the Australian Children’s Education and Care

Quality Authority (ACECQA), there were 15,417 children’s education and care

services operating in Australia in June 2015. This number included 14,317

centre‑based services and 1,100 FDC services (FDC services generally

consist of a coordination unit administering or supporting a number of

individual educators).[20]

Approvals

Provider

and service approvals

LDC, FDC and OSHC operators require a provider approval and

a service approval issued by state or territory regulatory authorities.

Provider approvals establish that an applicant is a fit and proper person to be

involved in the provision of education and care services.[21]

While a provider approval is issued by one regulatory authority, it is

recognised nationally and a provider does not need to have a separate approval

for each jurisdiction in which it operates a service.[22]

To receive a service approval, the provider must meet certain requirements to

ensure the safety, health and wellbeing of children attending the service; that

the service will meet the education and developmental needs of children

attending the service; and that the service complies with conditions prescribed

by the Education and Care Services National Law (the National Law),[23]

the Education and Care Services National Regulations (the National Regulations)[24],

or by the regulatory authority (all of these regulatory conditions form part of

the National Quality Framework (NQF)).[25]

Approval

for Child Care Benefit

Separate from the regulatory authority approval system is

the Australian Government’s determination that a service is ‘approved’ for CCB

purposes. CCB (and CCR) can only be paid to children using ECEC services that

have met the approved care requirements under family assistance law. These

requirements relate to the suitability of the operator/provider to provide the

appropriate quality of care; their reporting and information obligations to the

government; governance arrangements; hours of operation; the attendance of

school-age children at particular services; compliance with applicable

Australian Government legislation and regulations and with applicable state and

territory regulations (including the National Law and the National

Regulations).[26]

Occasional and in-home care services can also be approved care for CCB purposes

but do not currently have to meet the NQF requirements (but are required to

meet interim standards).[27]

CCB can be paid to non-approved ‘registered care’

providers—that is, grandparents, relatives, friends, neighbours, nannies or

babysitters who are registered as carers with the Department of Human Services.[28]

Australian

Government funding for early childhood education and care

The Australian Government provides fee assistance payments

to families and direct assistance to services to improve equity of access to

child care services, encourage and support the participation of women in the

workforce and to improve the quality of ECEC in order to assist with children’s

development.[29]

State and territory governments primarily fund or provide early childhood

education (preschool) services as well as regulating ECEC services operating

within their jurisdiction. Local governments also fund and provide ECEC services

in response to community need and facilitate access to services through their

role in land use planning.[30]

In 2014–15, total Australian and state and territory

government funding on ECEC services was $8.6 billion.[31]

The Australian Government’s expenditure accounted for 83.0 per cent ($7.1

billion) of this total.[32]

The main components of the Australian Government’s funding for ECEC is fee

assistance payments, however, $356.2 million was provided to state and

territory governments in 2014–15 under the National Partnership Agreement on

Universal Access to Early Childhood Education (not included in the $7.1

billion total).

Table 1 sets out the expenditure estimates for key

components of the Australian Government’s funding for ECEC, including the new

CCS and Early Childhood Safety Net (included in the Child Care Services Support

funding):

Table 1: Key components of Australian Government child

expenditure, budget estimates, $’000

| |

2015–16

Estimated actual1 |

2016–17 Budget |

2017–18 forward

estimate |

2018–19 forward

estimate |

2019–20 forward

estimate |

| Child Care Benefit |

4 008 613 |

4 238 005 |

4 437 718 |

|

|

| Child Care Rebate |

3 446 134 |

3 921 255 |

4 400 080 |

27 |

14 |

| Child Care Services Support2 |

258 069 |

376 781 |

376 801 |

358 579 |

365 692 |

| Jobs Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance |

39 439 |

39 119 |

38 749 |

|

|

| Child Care Subsidy |

|

|

|

11 056 787 |

12 192 035 |

1. Machinery of Government changes announced on 21 September

2015 saw responsibility for the main ECEC programs move from the Department of

Social Services to the Department of Education and Training. 2015–16 figures

represent the sum of the estimated actual expenditure figures reported for each

portfolio.

2. Does not include funding for the Early Years Quality Fund

Special Account. From 1 July 2017 the Early Childhood Safety Net will be

phased-in replacing most of the existing Child Care Services Support

sub-elements by 1 July 2018.

Sources: Australian Government, Portfolio

budget statements 2016–17: budget related paper no. 1.15a: Social Services

Portfolio, pp. 62–67; Australian Government, Portfolio budget statements

2016–17: budget related paper no. 1.5: Education and Training Portfolio,

pp. 25, 39.

According to the Department of Education and Training, in

the September quarter of 2015, there were 1,269,190 children and 859,380

families using approved care. An estimated 795,340 families were in receipt of

CCR.[33]

Child Care Benefit

CCB is paid to those using approved or registered care

services who meet the means test. Parents/carers using approved care services

can currently claim CCB for up to 50 hours of care per child per week (either

as a fee reduction paid directly to the child care provider or as a lump sum at

the end of the financial year). Single parents and both parents/carers in a

couple family must meet the work, training or study test for at least 15 hours

per week (or have an exemption) to be eligible for more than 24 hours of CCB

per child per week. The work, training or study test looks at whether the

parent(s)/carer(s) used child care for work-related commitments such as paid

work, looking for work, studying, training or volunteering.

CCB for registered care is paid when a claim is made to the

Department of Human Services and can be for up to 50 hours of child care per

week for a non-school-aged child. For registered care, both parents/carers or

the single parent/carer must meet the work, training or study test at some time

during the week child care is used (there is no minimum requirement and

exemptions from the test can be granted).

Eligibility for CCB requires parents/carers have their child

up to date with the age-appropriate immunisation schedule (or an approved catch

up schedule).[34]

Income test and payment rates

For those using approved care, the maximum CCB rate is

payable to those families with an adjusted taxable income under $44,457 or to

families on income support.[35]

Family income over this amount reduces the maximum CCB rate and families with

income above the income limit will not receive any CCB. The income limit for

one child in care is currently $154,697. The income limit for two children is

$160,308. For three children it is $181,024 (+$34,237 for each child after the

third).[36]

The current maximum CCB rates are:

- for

approved care: up to $4.24 per hour for a non-school child ($212.00 for a 50

hour week)

- for

registered care: $0.708 per hour, up to $35.40 per week.[37]

Rates for school children are 85 per cent of the

non-school child rates.

The calculation of CCB entitlements is complex with

different rate adjustment factors taking account of the number of children a

family has attending ECEC services, the type of service attended, the hours

attended, whether the children are school or non-school children, the family’s

adjusted taxable income, the standard hourly rate payable and the hours of care

the family is eligible to receive CCB for (under the work, training or study

test).[38]

Grandparent Child Care Benefit

Grandparent Child Care Benefit is a component of CCB payable

to grandparents who are the primary carers of their grandchildren, meet the

other CCB eligibility requirements and receive an income support payment.

Grandparent Child Care Benefit covers the full cost of the

total fee charged for CCB eligible hours, up to 50 hours per child per week. It

is paid directly to ECEC services.[39]

Special Child Care Benefit

Special Child Care Benefit (SCCB) is another component of

CCB. SCCB provides extra assistance with the costs of child care for families

and children in special circumstances, covering up to the full cost of child

care for a certain period of time or providing additional hours of care on top

of the usual CCB entitlement. There are two types of SCCB—one which is intended

to help children at risk of abuse or neglect, and another intended to help

families who are experiencing financial hardship in exceptional circumstances.

The SCCB rate is not a set amount and will usually cover the

entire cost of the fees for the particular ECEC service. The general rules for

CCB eligibility and attendance at child care apply. However, where a parent or

carer is not eligible for CCB (for example, where they have not lodged an

application form) and an approved child care service has concern for a child in

regards to abuse or neglect, the child care service can itself apply to be

eligible to receive SCCB on behalf of the child.[40]

SCCB is generally payable for periods of up to 13 weeks.

Only the Department of Human Services can approve SCCB for periods longer than

13 weeks.

Child Care Rebate

CCR is a separate payment from CCB and assists families with

their out-of-pocket costs for approved child care (but not registered care).

Out-of-pocket costs are total fees minus CCB. CCR covers 50 per cent of

out-of-pocket costs up to a maximum of $7,500 per financial year per child

(this amount is usually indexed to CPI but indexation has been paused since

2011–12).[41]

To be eligible for CCR an individual must be eligible for

CCB. Parents/carers can still be eligible for CCR even if receiving no CCB

because of a high income because CCR is not means tested. That is,

parents/carers must meet all the eligibility criteria for CCB except for the

income test (the requirements relating to the care relationship with the child,

residency, the work, training or study test, and immunisation).

CCR does have an activity test (both parents/carers or

single parents/carers must work, study or train at some time during the week in

which child care is used), however, there is no minimum number of hours for

such activities.

CCR is paid either fortnightly, to families or directly to

ECEC service, or as an annual lump sum to the family.

Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance

The Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance

(JETCCFA) program helps certain income support recipients (primarily payments

for the unemployed such as Newstart Allowance, Parenting Payment and Youth

Allowance (Other)) who are undertaking work, study or training, with the costs

of child care by covering most of the gap between the total childcare fee and

the amount CCB will cover.[42]

Parents and carers need to make a contribution of one dollar per hour per child

in ECEC and JETCCFA will cover the remaining fee cost (after CCB has been

deducted) for eligible hours up to $8.28 per hour per child.[43]

Any remaining costs over the JETCCFA cap have to be met by the parent (with 50

per cent of any remaining out-of-pocket costs covered by CCR). The number of

eligible hours depends on the activity being undertaken by parents: those

undertaking an approved activity as part of the Job Plan or Participation Plan

attached to their income support payment can receive up to 24 hours of JETCCFA

assistance per week per child; those undertaking a study or training activity

can receive up to 36 hours per week per child.[44]

Eligibility for the JECTCCFA program is for a limited

time—jobseekers are only eligible for up to 20 days while other categories of

recipients (students or participants in a labour market program) may be

eligible for 26–104 weeks of JETCCFA.

Funding for providers and quality support

Apart from fee subsidies, the Australian Government provides

funding for ECEC services directly via the Child Care Services Support

Programme. This program includes:

- the

Community Support Programme which provides funding for the establishment or

maintenance of ECEC services in areas where the services might not otherwise be

viable or able to meet the requirements of the community (particularly

communities in disadvantaged, regional and remote areas)

- the

Budget Based Funded Programme which contributes towards the operational costs

of just over 300 ECEC services in approved locations, primarily regional,

remote and Indigenous communities and

- the

Inclusion and Professional Support Programme which funds services to provide

the ECEC sector with professional development, advice, access to additional

resources and inclusion support for services and educators.[45]

Jobs for

Families Package

The Jobs for Families Child Care Package was announced as

the Government’s response to the Productivity Commission’s (PC’s) report on

child care and early childhood learning.

Soon after winning government (on 22 November 2013), then

Treasurer, Joe Hockey, requested the PC undertake an inquiry into ‘Child Care

and Early Childhood Learning’ to report by the end of October 2014.[46]

The PC released an issues paper on 5 December 2013 and a draft report on 22

July 2014. The final report was provided to the Government on 31 October 2014

and published on 20 February 2015.[47]

Details of the report’s findings and recommendations are set out in the Bills

Digest for the previous Bill.[48]

Just prior to the 2015–16 Budget, the Abbott Government

announced its response to the PC’s report: the Jobs for Families child care

package.[49]

The centrepiece of the package is the Child Care Subsidy (CCS) which is to

replace CCB, CCR and JETCCFA. Key features of the CCS as announced were:

- a

subsidy based on a percentage of an hourly benchmark price or the actual fee,

whichever is lower, with the benchmark to be set by Government and

differentiating between service type (LDC, FDC, OSHC and in-home care). The

benchmark price, known as the hourly fee cap, is based on the projected average

price for 2017–18, plus 17.5 per cent for LDC and OSHC and plus 5.75 per cent

for FDC.[50]

The hourly fee caps will be:

-

LDC:

$11.55 per hour

- OSHC:

$10.10 per hour

-

FDC:

$10.70 per hour

- In-home

care: $7.00

- a

subsidy rate of 85 per cent of the benchmark price or actual fee for families

with incomes at or below $65,000 per annum, tapering by one percentage point

for every $3,000 in income over this threshold to 50 per cent for family

incomes at or above $170,000

- families

with incomes over $185,000 will have their CCS entitlement capped at $10,000

per child per year

- hours of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) to be

subsidised based on the hours parents/carers spend undertaking approved

activities in a fortnight:

-

8–16

hours = up to 36 hours of CCS

- 17–48

hours = up to 72 hours of CCS

-

49

hours and above = up to 100 hours of CCS

- for couple families, the partner with the lower number of hours

of activity determines the CCS entitlement

- approved

activities will include work, training, study or certain other recognised

activities such as volunteering as well as participation requirements for

income support payments (such as Newstart Allowance, Parenting Payment and

Youth Allowance (Other))

- families

with incomes of up to $65,000, who do not meet the activity test, will be

eligible to receive up to 24 hours of CCS per fortnight under a separate

program known as the Child Care Safety Net

- the

Child Care Safety Net will replace the existing Inclusion and Professional

Support Programme, the Community Support Programme and the Budget Based Funded

Programme and will include the Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS), a new

Inclusion Support Programme and the Community Child Care Fund:

-

the

ACCS will provide additional assistance, on top of the CCS, to disadvantaged or

vulnerable families

- the

Inclusion Support Programme will assist services with staff training and

equipment to support children with special needs

-

the

Community Child Care Fund will provide grants to child care services to improve

access in disadvantaged areas, areas of high demand but low availability, and

to improve affordability for low income families in areas where fees are

greater than the CCS benchmark.[51]

CCS for in-home care is to be trialled via a pilot scheme,

the Nanny Pilot Programme, which will support up to 10,000 children in families

who find it difficult to access mainstream child care services.[52]

The pilot commenced at the beginning of 2016 and will run for two years.

Providers were selected from a field of applicants with nannies only required

to hold a working with children check and first aid qualification (as well as

residency requirements).[53]

Under the Budget measures, an additional $3.2 billion over

five years was to be provided for the introduction of the CCS, and additional

funding of $327.7 million over four years was to be provided for the Child Care

Safety Net.[54]

The additional funding for the CCS includes $246 million over two years for the

nanny pilot program.

Revised Jobs for Families package

In December 2015, the Government announced that it had

revised the package following consultation with parents and stakeholders and

following difficulties in passing savings measures from the Family Tax Benefit

program in the Parliament.[55]

Under the revised package, the percentage of the benchmark price covered by the

CCS would be set at 50 per cent of the benchmark price for families on incomes

between $170,000 and $250,000 per annum but would then continue to taper for

families on incomes over $250,000 until it reached the base rate of 20 per cent

of the benchmark price (for incomes at or above $340,000 per annum).[56]

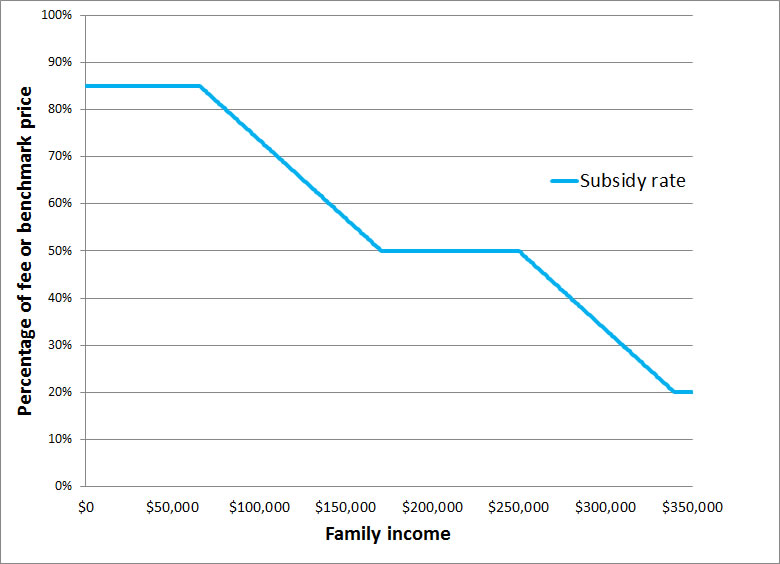

The revised income test is set out in Table 2 and illustrated in Chart 1:

Table 2: Revised Child Care Subsidy income test

|

Family income*

|

Subsidy rate – percentage of actual fee or benchmark price,

whichever is lower

|

|

Up to $65,710

|

85 per cent

|

|

More than $65,710 to below $170,710

|

Tapering from 85 to 50 per cent

|

|

$170,710 to below $250,000

|

50 per cent

|

|

$250,000 to below $340,000

|

Tapering from 50 to 20 per cent

|

|

$340,000 or more

|

20 per cent

|

* Due to the delayed commencement of the package, these

thresholds will be indexed according to movements in the Consumer Price Index

(CPI) for implementation on 1 July 2018 (so will be slightly higher).

Source: Department of Education and Training (DET), Overview: Jobs for Families

child care package, DET, Canberra, 3 May 2016.

Chart 1: Rate of Child Care Subsidy by family income

Source: Parliamentary Library estimates.

The changes to the income test contributed to a reduction

in the estimated expenditure on the CCS. In the Portfolio Budget Statements

released in May 2015, the CCS was expected to cost $21.02 billion in its first

two years, but in the Portfolio Additional Estimates released in February 2016,

the estimated expenditure in the first two years was expected to be $19.87

billion, a reduction of around $1.15 billion.[57]

On 29 November 2015 the Government also announced that

grandparent carers (those who have care of their grandchildren for more than 65

per cent of the time) would be made exempt from the CCS activity test and thus

eligible for up to 100 hours of subsidised care per fortnight.[58]

Grandparent carers in receipt of income support (such as the Age Pension) would

be eligible for a rate of up to 120 per cent of the CCS benchmark price.

The Regulation Impact Statement accompanying the Bill

confirmed that the Government’s preferred option is to retain the activity test

exemptions for CCB as the activity test exemptions for the CCS but would add an

additional exemption for families whose child is attending a preschool program

in an LDC centre (for the period of the preschool program).[59]

Impact of the revised package

The Department of Education and Training’s submission to the

Senate inquiry into the previous Bill outlined the estimated impact of the

revised package on families. The department used administrative data from the

Legislative Out-years Customisable Model of Child Care (LOCMOCC) as at the Mid-Year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2015 to estimate that around 815,700 families

will receive a higher level of fee assistance under the changes compared to the

current funding model; around 140,500 families will receive around the same

level of assistance and around 183,900 families will receive a lower level of

assistance.[60]

Of the 250,000 families earning $65,710 or less per year

(the lower income threshold):

- around

104,100 will be better off (will receive a greater level of assistance than

under the current system)

- around

81,000 will experience no change in the level of support

- around

52,100 will be worse off, primarily because of the impact of the activity test

and

- around

12,800 families are on income support and have not reported their income and

the department was unable to determine the impact of the changes on them.[61]

Of the 653,900 families with income between $65,710 and

$170,710:

- around

565,400 will better off

- around

32,800 will experience no change and

- around

55,700 will be worse off, either because they do not meet the activity test

requirements or are paying child care fees in excess of the hourly fee cap.[62]

Of the 178,500 families with income between $170,710 and

$250,000:

- around

142,400 families will be better off

- around

19,500 will experience no change and

- around

16,600 families will be worse off, primarily as a result of paying child care

fee in excess of the hourly fee cap.[63]

Of the 70,500 families with income over $250,000:

- around

3,800 families will be better off

- around

7,200 will experience no change and

- around

59,500 families will be worse off.[64]

The Minister for Education and Training has stated

families earning between $65,000 and $170,000 will ‘be around $30 a week better

off as a result of the child care reforms’.[65]

In an Answer to a Question on Notice from the 2015–16

Senate Additional Estimates hearings, the Department provided a breakdown of

those who would receive a lower subsidy rate under the changes, by reason

(these figures do not include 30,500 families who are likely to be ineligible

for subsidy under the changes)—set out in Table 3.

Table 3:

Families expected to receive a lower subsidy rate by income band, 2017–18

|

Reason for potential decrease in subsidy

|

Families by

income band

|

|

Less than

$65,710

|

$65,710 to less

than $170,710

|

$170,711 to

less than $250,000

|

$250,000 or more

|

|

Activity test

|

28,000

|

7,600

|

500

|

900

|

|

Hitting fee cap

|

6,200

|

10,500

|

13,700

|

16,100

|

|

Both activity test and fee cap

|

1,200

|

1,000

|

200

|

600

|

|

Other reason

|

16,800

|

7,000

|

1,600

|

18,300

|

|

Reduction in subsidy level

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

23,200

|

|

Total families receiving lower subsidy

|

52,100

|

26,100

|

16,000

|

59,200

|

Notes: Estimates based on Legislative Out-years Customisable

Model of Child Care (LOCMOCC) as at the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook

2015. Totals may not match due to rounding. Families may receive less

subsidy under CCS due to other reasons which cannot be separately identified.

Source: Senate Education and Employment Committee, Answer to

Question on Notice, Education and Training Portfolio, Additional Budget

Estimates 2015–16, Question

SQ16-000142.

The Minister stated that ‘some 240,000 Australian families

are estimated to increase their workforce participation and involvement as a

result of the reforms’.[66]

This figure is based on the results of an online survey conducted by ORIMA

Research of approximately 2,000 people where 24 per cent indicated they would

be willing to work more as a result of the measures (as proposed in the

Budget).[67]

This 24 per cent figure was applied to 2011 census data on the number of

families using child care to give the estimate of 240,000 families who would

increase their participation involvement as a result of the reforms.[68]

The department has not released the research report this data is taken from,

and a redacted version of two pages from the report released under Freedom of

Information provided no further information.[69]

The estimated impact on workforce participation derived

from this survey is of limited use as it based on respondents indicating a

willingness to work more and does not quantify the amount of additional labour

market activity. The PC provided a detailed model for assessing the labour

force impact of its proposed model (estimating that the changes would result in

increased workforce participation equivalent to an additional 16,000 full-time

equivalent workers).[70]

PricewaterhouseCoopers conducted an economic impact analysis of the CCS as

proposed in the 2015 Budget (for childcare provider Goodstart Early Learning)

and found that by 2050, an additional 29,000 full-time equivalent workers will

have joined the workforce as a result of the payment model (with around half of

this impact derived from existing workers increasing their hours).[71]

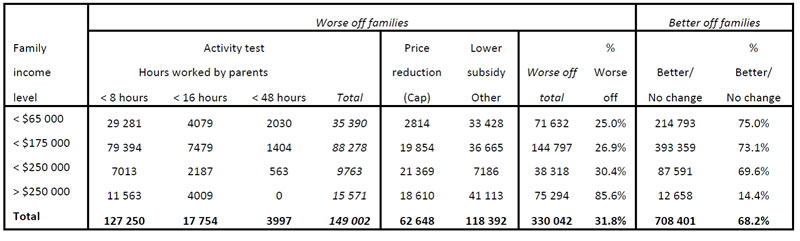

Early Childhood Australia also commissioned distributional

modelling of the proposed reforms from the Australian National University’s

(ANU) Centre for Social Research and Methods.[72]

This modelling was based primarily on unit record data from the Australian

Bureau of Statistics’ Survey of Income and Housing 2013–14 with prices and

parameters adjusted to analyse the impact in 2017–18. The modelling found that

an estimated 582,000 families will be better off under the package compared to

the current fee assistance arrangements, around 330,000 families will be worse

off and 126,000 families will receive around the same level of subsidy as they

currently do. The detailed impact is set out in this table from the report:

Table 4: ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods

modelling of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ from proposed Jobs for Families

policy—families

Notes: this model projects around ten per cent fewer families

using child care by 2017–18 than projected by the Department of Education and

Training (possible reflecting different data sources). Around 6,600 families

are impacted by both the activity test and hourly price cap—all families in

this group are counted towards the activity test. All families in receipt of

income support payments, except for Parenting Payment (Single) and partnered

families with children aged under six are assumed to have passed the activity

test due to job search requirements attached to those payments.

Source: B Phillips, Distributional

modelling of proposed childcare reforms in Australia, ANU Centre for

Social Research and Methods, Canberra, March 2016, p. 7.

The ANU’s modelling projects a much larger group of ‘losers’

as a result of the reforms than the Department of Education and Training has

projected. Of the estimated 330,000 worse off, around 149,000 are affected by

the proposed activity test.[73]

The report notes that the main driver of the difference between its estimates

of those worse off and those of the department is a much lower activity test

impact estimated by the department.[74]

The report notes the administrative data used for the department’s estimates

has only limited information on the hours worked by parents compared to that

offered by the ABS Survey.[75]

The administrative data is advantaged by having data on the full population of

families using approved childcare (including adjusted taxable income) compared

to a limited survey sample of 1,100 income units using formal child care

offered by the ABS Survey.

Committee consideration

Previous

consideration

Senate Education and Employment Committee

The previous Bill was referred to the Senate Education and

Employment Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 17 March 2016. On 17

March 2016, the Senate granted an extension of time for reporting until

4 April 2016 and the Committee tabled its report on that date. Details

of the inquiry are on the Committee’s

website.[76]

The Committee recommended the previous Bill be passed

without amendment.[77]

While noting the concerns of some interest groups particularly in regards to

the activity test, the Committee found that the provisions of the previous Bill

would ‘target taxpayer support to encourage workforce participation while

providing the safety net for those families on lower income’.[78]

The Committee report stated that ‘the activity test provisions of the Bill are

a fair and equitable way to ensure that the Child Care Subsidy is targeted at

best at the families who will need and use it most’.[79]

Both Labor Senators and Greens Senators issued dissenting

reports recommending amendments to the previous Bill.[80]

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee considered the previous

Bill in Alert Digest 1 of 2016.[81]

The Alert Digest raised concerns that subsection

27A(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 would not

apply to deemed refusals for either an application for a determination of risk

of serious abuse or neglect or for an application for a determination of

temporary financial hardship (at proposed subsections 85CE(4) and 85CH(5)

of the FA Act, at item 40 of Schedule 1 of both versions

of the Bill).[82]

Subsection 27A(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act

requires a notice of decision and review rights to be given to any person whose

interests are affected by the decision.[83]

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee stated that the Explanatory Memorandum for the

previous Bill did not provide a justification and sought the Minister’s advice

for the rationale for the proposed approach. The explanation provided in the

Explanatory Memorandum is that the deemed refusal provisions are not intended

to be relied upon and have only been included in the unlikely event that the Secretary

does not meet requirements to clarify the status of an application within 28

days.[84]

The Committee also raised concerns with the ‘Henry VIII’

clause (at proposed section 199G of the FA Admin Act, at

item 202 of Schedule 1 to the previous Bill and item 205 of Schedule 1

of the current Bill) and the power to make transitional rules (at Schedule

4, item 12 of both versions of the Bill). Henry VIII clauses are

those that enable delegated or subordinate legislation to override the

operation of legislation which has been passed by the Parliament. The Scrutiny

of Bills Committee raises concerns in regards to such clauses when the

rationale for their use is not provided or is insufficient as ‘such clauses may

subvert the appropriate relationship between the Parliament and the Executive

branch of government’.[85]

In this instance, the Committee sought advice from the Minister as to whether

these clauses could be drafted to ensure the provisions are only used

beneficially (as is their stated intent in the Explanatory Memorandum).[86]

The Committee also sought advice from the Minister regarding

strict liability offences, stating that the Committee expects ‘a detailed

justification of each instance of the application of strict liability’.[87]

The Committee stated that these provisions may be considered to trespass unduly

on personal rights and liberties.[88]

Consideration

of the 2016 Bill

Senate

Education and Employment Legislation Committee

The current Bill was referred to the Senate Education and

Employment Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 10 October 2016,

together with the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Family Payments

Structural Reform and Participation Measures) Bill 2016 (which contains the

Family Tax Benefit savings measures that have been linked with the additional

expenditure on the Jobs for Families Child Care Package). The Committee tabled

its report on that date. Details of the inquiry are on the Committee’s

website.[89]

The Committee recommended both Bills be passed without

amendment. The report noted the concerns from some interest groups (outlined in

the ‘Position of major interest groups’ section below), particularly in regards

to the activity test and a perceived prioritisation of workforce participation

objectives over children’s needs. The report stated that ‘the committee is not

persuaded that a focus on workforce participation has come at the expense of

the needs of children, and is of the view that the Bill can achieve both’.[90]

The Committee also found that the Bill would ‘result in a fairer system, where

low income families receive more help and subsidies to high income families

fall’.[91]

Both the Australian Labor Party (Labor) and the Australian

Greens (Greens) issued dissenting reports. The Nick Xenophon Team also issued

additional comments on the report. These are discussed in the ‘Policy position

of non-government parties/independents’ section below.

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

commented on the Bill in Alert Digest 7 of 2016.[92]

The Committee noted that it had previously commented on the measures as

presented in the previous Bill and restated those comments with some

modifications. The Committee had received correspondence from the Minister for

Education and Training in March 2016 in response to the issues raised in Alert

Digest 1 of 2016.

The Minister addressed the issue of certain deemed refusals

(under proposed subsections 85CE(4) and 85CH(5), at item 40 of Schedule

1 in both versions of the Bill) being exempt from the requirements under

subsection 27A(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975

(AAT Act) to give a notice of decision and review rights to any

person whose interests are affected by the decision, stating:

Subsection 27A(1) of the AAT Act provides that a

person who makes a reviewable decision must take reasonable steps to give to an

affected person a written notice of the decision and of their review rights. It

would not be appropriate to require the Secretary to give a decision notice

advising of review rights in relation to deemed refusals under subsections

85CE(4) and 85CH(5), because deemed refusals only come into effect in

circumstances where the Secretary, (or his or her delegate), has failed to

personally make a decision: in other words, no actual decision was made by an

officer. Accordingly, proposed subsections 85CE(4) and 85CH(5) simply reflect

that it would be inappropriate to oblige the Secretary to notify of the act of

not making an active decision. As such, the exemption from the notification

requirement merely reflects the practical reality that any deemed refusals are

likely to occur without the Secretary’s actual and active knowledge.[93]

The Minister’s justification here is that while a

determination has been made that means a child is not deemed to be at risk or a

family in temporary financial hardship, the decision was ‘not made personally’

and is not an ‘active decision’.

While such deemed refusals are expected to be rare, it is

unclear how applicants will become aware that the application has been refused

other than by contacting the department to ask about the progress of their

application. They would also need to ask about their review rights.

The Committee had no further comments to make in relation

to these provisions in light of the information provided by the Minister and

its inclusion in the Explanatory Memorandum to the current Bill.[94]

In regards to the concerns the Committee had raised

regarding the Henry VIII clause at proposed section 199G of the FA

Admin Act and its suggestion that the clause be redrafted so that it could

only be used for beneficial purposes, the Minister responded:

Although it may be possible to include limiting words to

ensure the provisions are only used beneficially, amendments of this nature

could be equivocal and possibly confusing due to difficulties in defining what

a ‘benefit’ is in the context of lifting obligations relating to backdated

approvals. I note that any rules made in accordance with section 199G will be

subject to further parliamentary scrutiny through the disallowance process for

legislative instruments, which means that Parliament will be able to disallow

any rules that are considered non-beneficial or otherwise unfair.[95]

The Committee did not accept that this was a compelling

justification for broadening the scope of delegated powers to override the

operation of the primary legislation:

While the committee notes that the intention is for

modifications to be beneficial, the suggestion that limiting words ‘could be

equivocal and possibly confusing’ is not a compelling justification for

broadening the scope of delegated powers.

The committee draws the breadth and nature of this power

to the attention of Senators and, noting that any rules made in accordance with

section 199G will be subject to disallowance, leaves the question of whether

the proposed approach is appropriate to the consideration of the Senate as a

whole.[96]

In relation to the Committee’s concerns regarding the

Henry VIII clause at item 12 of Schedule 4 (the transitional

rules), the Minister argued in his letter to the Committee that the power was

justified given it would only operate for a limited period of two years and the

rules would be subject to disallowance by the Parliament.[97]

The Committee noted the justification provided and left

the question whether the scope of this delegation of legislative power is

appropriate to the Senate as a whole to consider.[98]

In regards to the Committee’s request for a detailed

justification of each application of strict liability, the Minister had

responded with a rationale for various strict liability offences and included

further information on these provisions in the Explanatory Memorandum for the

Bill (additional to that provided in the Explanatory Memorandum for the

previous Bill).

The Committee found that these explanations appeared to be

consistent with the Guide to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement

Notices and Enforcement Powers (the Guide).[99]

However, it found that the ability to impose penalties above 60 penalties units

is not.[100]

The Committee noted that the Minister had advised that these higher penalties

were considered appropriate in order to promote compliance with family

assistance law but stated:

... it remains the case that in order to be consistent with the

principles outlined in the Guide ... strict liability offences should be applied

only where the penalty does not include imprisonment and the fine does not

exceed 60 penalty units for an individual.[101]

The Committee left the question of whether this approach

is appropriate to the Senate as a whole to consider. It also drew attention to

the provisions as ‘they may be considered to trespass unduly on personal rights

and liberties’.[102]

The Committee also commented on new provisions (items 1

and 2 of Schedule 3) not contained in the previous Bill.[103]

These items allow for a determination made by the Minister in relation to

immunisation requirements for certain payments to adopt or incorporate matters

set out in another written instrument. Without this authorisation, subsection

14(2) of the Legislation Act 2003 would prevent this approach.[104]

The Explanatory Memorandum explains that this is ‘intended to ensure that

future versions of the instruments that set out vaccination and immunisation

details and schedules (including the Australian Immunisation Handbook)

can continue to be meaningfully referred to’.[105]

The Committee acknowledged the comprehensive justification for the provisions

in the Explanatory Memorandum and did not make any further comment on the measures.[106]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Australian

Labor Party

Labor Senators issued a dissenting report to the Senate

Education and Employment Committee’s report on the Bill.[107]

Labor Senators stated that the issues identified in their dissenting report to

the inquiry into the previous Bill remained. These included concerns over the

impact of the activity test, the impact on Budget Based Funded Indigenous and

Mobile services, and the limited information available on delegated legislation

to be made under the Bill and on the Government’s proposed Community Child Care

Fund.[108]

Labor Senators also raised a new concern over the delay in providing additional

funding for ECEC (as a result of the delayed commencement of the package).[109]

Labor Senators also rejected the Government’s proposal to

link savings from the Family Tax Benefit program with any additional funding

for ECEC:

The link between the Jobs for Families Bill and the Social

Services Bill has been artificially devised for political purposes and is not

supported by Labor. Investment in early education should not be held hostage to

Family Tax Benefit cuts. This is robbing Peter to pay Paul: taking money from

low income families to give to other families through child care assistance.[110]

Labor Senators stated that they are concerned that too

many families would be worse off under the Jobs for Families child care package

and called on the Government to amend the Bill to ‘improve the balance between

children’s early education and parent’s workforce participation’.[111]

Recommendations from the Labor Senators include:

- continuing

to provide all children with access to two days early education a week and for

any changes to current activity tests to be trialled before introduction

- an

immediate increase in assistance for families to cover the period prior to the

Jobs for Families package commencing in July 2018

- not

making additional funding for ECEC conditional on cuts to Family Tax Benefit

expenditure.[112]

The Dissenting Report did not include a recommendation

that the Bill be opposed, only that the Bill containing the Family Tax Benefit

savings be rejected.

Australian

Greens

The Greens stated in their dissenting report that while

supporting the aims of the Bill, the Greens were concerned that ‘the measures

included in this Bill as currently drafted will not achieve these aims, and

will in fact result in a number of families being unable to access childcare or

receive reduced access to subsidised care’.[113]

The Greens were particularly concerned with the impact of the proposed activity

test and also on the closure of the Budget Based Funding program under the Jobs

for Families Package (a component of the package but not the Bill).

The Greens made a number of recommendations including

changes to the activity test so that families with 0–8 hours of activity would

be eligible for two days of subsidised care.[114]

Nick

Xenophon Team

The Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) issued additional comments to

the Senate Education and Employment Committee’s report on the Bill and raised a

number of concerns in relation to the impact of the activity test on ECEC

providers and workers and the Department of Education and Training’s

consultation procedures.[115]

NXT also sought clarification from the Department regarding ongoing funding for

in-home care services.[116]

Position of

major interest groups

The positions of major interest groups were canvassed in

detail in the Bills Digest for the previous Bill and the concerns raised by

these groups previously have not changed.

In relation to the 2016 Bill, three peak bodies (Early

Childhood Australia, Australian Childcare Alliance and the Early Learning and

Care Council of Australia) joined with the largest child care provider,

Goodstart Early Learning, to issue a joint submission to the Senate Education

and Employment Committee’s inquiry into the Bill.[117]

The four organisations reiterated their support for the broad thrust of the

Jobs for Families Package and their continued concern over the impact of the

activity test.[118]

The joint submission held that the base CCS entitlement for low income families

who do not meet the activity test should be increased from 12 hours per week to

15 hours per week. The submission also proposed raising the income threshold

for this base entitlement from $65,710 to $100,000 arguing that 56 per cent

children considered developmentally vulnerable under the Australian Early

Development Census are from the least advantaged 40 per cent of families.[119]

The submission also identified some potential areas for savings to cover the

cost of their proposed changes and identified areas for further discussion. The

submission also argued that the additional funding for the Jobs for Families

Package should be decoupled from the proposed Family Tax Benefit savings

measures.[120]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that the

Child Care Subsidy and Additional Child Care Subsidy will cost $23.37 billion

over two years from 2018–19.[121]

As illustrated in Table 1 (above), most of this funding

will be redirected from existing ECEC programs. The Explanatory Memorandum for

the Bill states that an additional $3 billion in additional expenditure will be

provided to support the implementation of the Jobs for Families Child Care

Package.[122]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary

Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bill’s

compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the

international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government

considers that the Bill is compatible.[123]

Parliamentary

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights listed the

Bill in its seventh report of 2016 as not raising human rights concerns.[124]

In regards to the previous Bill, the Committee stated in its

33rd report of the 44th Parliament that the Bill reintroduced measures

previously considered by the Committee, and that the Bill ‘continues

arrangements in relation to the Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab,

No Pay) Bill 2015 which the committee previously considered’.[125]

While the immunisation requirements introduced under the No Jab, No Pay Bill

are continued under the new child care payment arrangements, this is a

relatively minor part of the proposed changes.

The Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights lists a

number of human rights treaties that the Bill engages with but the Committee appears

to have determined that any human rights limitations are permissible.

Key issues

and provisions

The key issues and provisions are discussed in detail in

the Bills Digest for the previous Bill.[126]

This section will only highlight significant differences between the two

versions of the Bill.

The Department of Education and Training provided a full

list of differences between the Bill and the previous Bill, and the reasons for

the change, in Attachment 2 to its submission to the Senate Education and

Employment Committee’s inquiry into the Bill.[127]

Table 5 sets out key changes between the two versions of

the Bill. Other changes primarily relate to date changes (due to the delayed

commencement of the Bill) and corrections or amendments in response to drafting

errors in the previous Bill.

Table 5:

Key differences between the 2015 and 2016 versions of the Jobs for Families

Package Child Care Bill

|

Key changes or

new provisions

|

Explanation

|

|

Additional Child Care Subsidy (ACCS) (at risk) has been

renamed ACCS (child wellbeing) and all relevant references throughout the

Bill have been amended.

|

The Department of Education and Training explained that

this change was in response to feedback from the ECEC sector that the ‘at

risk’ name could deter families from accessing the additional support ACCS

provides, ‘which is at odds with the policy intent’.[128]

|

|

The lower income threshold, CCS hourly rate caps and CCS

annual cap will be adjusted upon commencement to reflect CPI movements (by item

5 of Schedule 4)

|

Certain amounts in the previous Bill were to be adjusted

once a year on 1 July in line with CPI movements. Due to the commencement of

the CCS being delayed for a year, until 2 July 2018, the amounts

set out in the Bill for the lower income threshold, CCS hourly rate caps and

CCS annual cap will be lower than initially intended for 2 July 2018. The new

provision provides for indexation of these amounts to occur on 1 July 2018,

despite the amounts not existing until commencement of the CCS on 2 July

2018. This will mean that each of these amounts and each of the income test

thresholds will be slightly higher than outlined above. All of the higher income

test thresholds will be increased as a result of the indexation of the lower

income threshold as they are set as whole dollar amounts above the lower

income threshold.

|

|

Proposed subsections 85BA(2) and 85CA(3) of the FA Act

(inserted by item 40 of Schedule 1) will give a new rule-making

power to the Minister so that children older than 13 years can be eligible

for CCS or ACCS.

|

The previous Bill limited eligibility to the CCS and ACCS

to children 13 years and under who do not attend secondary school. The new

power will enable the Minister for Education and Training to determine

circumstances in which children over the age of 13 and/or attending secondary

school may be eligible for CCS or ACCS. The Department of Education and

Training explained that this was in response to concerns from stakeholders

about the impact of this age limit on older children with disability and

their families, who may need to access child care services, such as outside

school hours care.[129]

|

|

Proposed section 85EE of the FA Act (inserted by item

40 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) has been changed to reduce the

period a person can be temporarily overseas and receive CCS or ACCS (the

portability period) from 56 weeks to six weeks.

|

The previous Bill allowed for temporary overseas absences

of up to 56 weeks, similar to the portability rules for Family Tax Benefit

(FTB) and CCB at the time. The FTB and CCB portability rules have since been

reduced to six weeks and the 2016 Bill has reduced the period for the CCS and

ACCS to six weeks. The portability rules for FTB and CCB were changed via the

Social Services Legislation Amendment (Family Measures) Act 2015.[130]

|

|

Proposed clause 12 of Schedule 2 of the FA Act

(inserted by item 41 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) has additional

subclauses setting out that ‘associated activities’, as prescribed by the

Minister’s rules, will also be taken to be ‘recognised activities’ under the

activity test, including taking leave or a break; and provide for the rules

to set out ways of working out the number of hours to be counted towards a

recognised activity and a maximum limit on the number of hours that can be

counted towards an activity.

|

This change will allow the Minister to create rules that

define or expand upon the list of activities listed in the Bill, to clarify what

kinds of activities constitute the recognised activities listed at proposed

subclause 12(2) of Schedule 2 to the FA Act and to limit the number of

hours which can be counted in respect of a particular activity. The

Department of Education and Training stated that these changes give better

effect to the policy intent of the rule-making powers.[131]

The Department suggested that the time-limits could be applied so as to

specify that hours spent volunteering could only be applied to the first step

of the activity test.[132]

This would mean that certain types of activity would only be eligible for a

set maximum amount of CCS hours, regardless of the total number of hours

spent in that activity.

|

|

Proposed clause 3AA of Schedule 3 of the FA Act (inserted

by item 45 of Schedule 1 to the Bill) provides a method for

working out adjusted taxable income for a member of a couple during CCS

fortnights, particularly where the person’s partner was not their partner for

the whole year.

|

This new clause provides for the proportion of a partner’s

income that is equivalent to the proportion of the financial year that the

partner was in a couple relationship with the CCS claimant to be included in

the income test. As CCS is to be worked out on a fortnightly basis, it

appears this provision has been included to allow for couple rates to be

calculated based on the fortnights a couple was together in a relationship.

This is different from other family assistance payments where rates are

calculated on an annual basis divided into a daily rate. For these payments, where

circumstances change during the year such as a person entering a couple

relationship, a different rate is calculated based on the relevant period

where the circumstances are changed (a new annual rate is calculated and a new

daily rate determined).

The Department of Education and Training’s submission to

the Senate Education and Employment Committee’s inquiry into the Bill notes

this new clause but only explains a related change at item 114 of Schedule

1 (relating to reconciliation provisions).[133]

It is unclear why CCS needs to make use of this new formula

for the income test rather than the existing family assistance provisions but

it appears that the Government would rather all aspects of the rate

calculation process be tied to the CCS fortnight structure.

A separate issue with this new clause is that it makes

reference to a ‘TFN determination person’ without a definition of this term.

A TFN determination person is not defined in the FA Act and is only

defined in the FA Admin Act (at section 3).

|

|

Proposed subsection 194E(d) of the FA Admin Act

(inserted by item 205 of Schedule 1) (which relates to one of the

factors the Secretary should have regard to in assessing whether someone is a

‘fit and proper’ person to be a provider or person responsible for the

day-to-day running of an approved child care service) has been reworded.

|

In the previous Bill, the proposed subsection stated the

Secretary should have regard to: ‘any conviction of a relevant person for an

offence against a law of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory’.

In the Bill, the proposed subsection reads: ‘subject to

Part VIIC of the Crimes Act 1914, any conviction, or finding of

guilt, against a relevant person for an offence against a law of the

Commonwealth or a State or Territory, including (without limitation) an

offence against children, or relating to dishonesty or violence’. The revised

paragraph will cover people who have been found guilty of an offence in

circumstances where a conviction has not been recorded.

The Department of Education and Training states that this

change was made to reflect the current eligibility determination.[134]

|

Concluding comments

The Bill proposes the most significant changes to child

care fee assistance arrangements in more than 15 years, aimed at making the

system simpler and more sustainable, while improving affordability for families

and increasing work participation incentives. Arguably, the system will remain