Bills Digest no. 13 2015–16

PDF version [1.15MB]

WARNING: This Digest was prepared for debate. It reflects the legislation as introduced and does not canvass subsequent amendments. This Digest does not have any official legal status. Other sources should be consulted to determine the subsequent official status of the Bill.

Paula Pyburne

Law and Bills Digest Section

20 August 2015

Contents

The Bills Digest at a glance

History of

the Bill

Purpose of

the Bill

Structure of

the Bill

Background

Committee

consideration

Statement of

Compatibility with Human Rights

Policy

position of non-government parties

Position of

major interest groups

Financial

implications

Key issues

and provisions

Schedule

1—eligibility

Schedule

2—rehabilitation

Schedule

3—scheme integrity

Schedule

4—provisional medical expense payments

Schedule

5—medical expenses

Schedule

6—household services and attendant care services

Schedule

7—absences from Australia

Schedule

8—accrual of leave while receiving compensation

Schedule

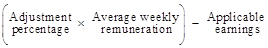

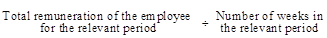

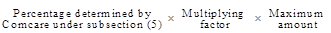

9—calculation of compensation

Schedule

10—redemption of compensation

Schedule

11—legal costs

Schedule

12—permanent impairment

Schedule

13—licences

Schedule

14—gradual onset injuries

Schedule

15—sanctions

Schedule

16—Defence related claims

Concluding

comments

Date introduced: 25

March 2015

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Employment

Commencement: various

dates set out in the table in section 2 of the Bill.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they

become Acts, which can be found at the ComLaw

website.

The Safety, Rehabilitation and

Compensation Amendment (Improving the Comcare Scheme) Bill 2015 makes profound

changes to the Comcare Scheme.

The Bill is one of three, the others being the Safety,

Rehabilitation and Compensation Legislation Amendment Bill 2014 and the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Legislation Amendment (Exit

Arrangements) Bill 2015. Debate was adjourned in the Senate in November 2014

for the first Bill and in May 2015 for the second.

The amendments to the Comcare Scheme are

said to be designed to make the Comcare Scheme ‘more sustainable over time’.

Limits to injuries

that are compensable

In order to achieve that, the Bill reduces

the types of injuries that are compensable by:

- distinguishing

between work and non-work related injuries

- introducing

new eligibility criteria for compensation for designated injuries (such as

heart attacks, strokes and spinal disc ruptures) and aggravations of those

injuries so that compensation is not payable unless the employee can prove that

either the underlying condition or the culmination of that condition is

significantly contributed to by his, or her, employment and

- widening

the scope of the ‘reasonable administrative action‘ exclusion to encompass

injuries suffered as a result of reasonable management action generally

(including organisational or corporate restructures and operational directions)

as well as the employee‘s anticipation or expectation of such action being

taken.

Limiting costs of the scheme

The Bill also takes the following steps to reduce costs to

the scheme:

- emphasising

return to work outcomes rather than the medical nature of rehabilitation

services

- limiting

legal and medical costs under the scheme

- limiting

the period for which household services and attendant services are payable to

an employee who has suffered a non-catastrophic injury and

- updating

the method for calculating weekly compensation and introducing a system of

‘step-downs’ to reduce the amount payable at set times after the injury was

sustained.

Creating a sanctions regime

In addition, the Bill introduces the concept of

‘obligations of mutuality’ which apply to injured employees. A breach of such

an obligation gives rise to a three level sanctions regime. Levels 1 and 2

sanctions operate to suspend the payment of weekly compensation to an injured

employee. Where a level 3 sanction is imposed on an injured employee it acts to

cancel the employee’s rights to payments of compensation, medical treatment and

other rehabilitation services.

All URLs accessed 20 August 2015.

The Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Amendment

(Improving the Comcare Scheme) Bill 2015 (the Bill) is the third Bill to be

introduced by the Government consistent with its policy to transform the

existing scheme by which workers’ compensation is paid.

The first Bill, the Safety, Rehabilitation and

Compensation Legislation Amendment Bill 2014 (the 2014 Bill), was introduced

into the House of Representatives on 19 March 2014 and is currently before the

Senate.[1]

The 2014 Bill contains amendments to the Safety, Rehabilitation and

Compensation Act 1988[2]

(SRC Act) to:

- expand

the class of corporations which are able to apply for a self-insurer licence.

The amendments enable those corporations which are currently required to meet

workers’ compensation obligations under two or more workers’ compensation laws

of a state or territory to apply to the Safety Rehabilitation and Compensation

Commission (the Commission) to join the Comcare scheme

- enable

the Commission to grant self-insurer group licences to related corporations and

makes consequential changes to extend the coverage provisions of the Work

Health and Safety Act 2011[3] to those corporations that obtain a licence to

self-insure under the SRC Act

- exclude

access to workers’ compensation where a person engages in serious and wilful

misconduct, even if the injury results in death or serious and permanent

impairment and

- exclude

access to workers’ compensation where injuries occur during recess breaks away

from an employer’s premises.[4]

The amendments in the 2014 Bill are opposed by the

Victorian and Queensland Governments on the grounds that they will seriously

undermine the relevant state workers’ compensation schemes.[5]

The second Bill is the Safety,

Rehabilitation and Compensation Legislation Amendment (Exit Arrangements) Bill

2015 (the Exit Arrangements Bill).[6]

That Bill is currently before the Senate, debate having been suspended

on 14 May 2015.

The Exit Arrangements Bill amends the SRC

Act to:

- provide

for financial and other arrangements for a Commonwealth authority to exit the

Comcare scheme

- clarify

that premiums should be calculated so that current and prospective liabilities

are fully funded and

- change

the appointment process and membership of the Commission.[7]

The provisions of the Bill should be read in the context

of the earlier Bills in order to appreciate the breadth of the proposed changes

to the Comcare scheme. Together they allow for more corporations to become self‑insurers

in the Comcare scheme whilst limiting the injuries which are compensable and

the amounts of compensation payable to employees.

The purpose of the Bill is to implement some of the

recommendations of the Review of the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation

Act 1988 by Peter Hanks QC (Hanks Report)[8]

and Dr Allan Hawke AC which had been commissioned by the former Labor

Government in 2012 (Hawke Report).[9]

In addition the Bill makes other changes to the SRC Act

that the Government claims will improve the viability of the Comcare scheme,

and align parts of the scheme with state schemes. For instance, the Bill

contains amendments to enable Comcare to recover overpayments of compensation

that have been made to an employer by Comcare.

The Bill contains 17 schedules:

- Schedule

1: makes a number of changes to the eligibility requirements for compensation

which will have the effect of limiting access to compensation for some employees

- Schedule

2: amends the rehabilitation and return to work requirements in the SRC Act

to emphasise the vocational—that is, return to work—aspects of rehabilitation

services, rather than the medical ones

- Schedule

3: amends the SRC Act to improve the financial viability of the Comcare

scheme as recommended by the Hanks Report. For instance, amendments in this

Schedule will require third parties to indemnify payers of compensation under

the SRC Act if there is also a liability to pay damages

- Schedule

4: contains amendments to provide for provisional medical expense payments in

respect of an alleged injury before a claim for compensation is determined

- Schedule

5: imposes more rigorous requirements in relation to determining the amount of

compensation payable for medical expenses which are incurred by an injured

employee

- Schedule

6: amends the SRC Act to create two categories of injury—catastrophic

and non-catastrophic. Those employees who have suffered a non-catastrophic

injury who are entitled to payment of compensation for household services and

attendant care services will receive them for a maximum period of three years

- Schedule

7: amends the SRC Act to suspend payment of compensation when an injured

employee is absent from Australia for private purposes for a period of more

than six weeks

- Schedule

8: will operate so that an employee is not entitled to take or accrue any

leave, or absence, as provided for by the National Employment Standards while

on compensation leave, receiving compensation

- Schedule

9: sets out the new method of calculating weekly workers’ compensation and

introduces ‘step down’ provisions to taper the amount of weekly incapacity

payments to which an injured employee is entitled. The effect is to reduce the

amount of weekly compensation payable after the first 13 weeks and at specified

points thereafter

- Schedule

10: amends the SRC Act to increase the amount at which Comcare must

redeem its liability to future payments by way of a lump sum. As the threshold

amount is higher than under the SRC Act at present it will set the

trigger for a mandatory redemption earlier than it is at present

- Schedule

11: will operate to limit the overall amount of costs that may be awarded or

reimbursed to a claimant in certain circumstances

- Schedule

12: contains provisions to combine the compensation payable for permanent

impairment and compensation payable for non-economic loss—which are currently

separate payments—into a single permanent impairment payment—and to increase

the existing maximum amount payable for permanent impairment

- Schedule

13: will clarify that a single employer licence for an eligible corporation or

group employer licence must authorise acceptance of liability and management of

claims and that a single employer licence for a Commonwealth authority must

authorise acceptance of liability or management of claims—or both

- Schedule

14: amends the SRC Act so that compensation responsibilities for gradual

onset injuries and associated injuries will generally rest with the most recent

employer

- Schedule

15: imposes obligations upon injured employees (called obligations of

mutuality) to take a specified action which an employer requires. It also

provides for the imposition of sanctions—suspension of weekly payments and

possible cancellation of an employee’s entitlement to compensation—where those

obligations have been breached

- Schedule

16: operates so that the amendments made by the other schedules in the Bill,

with some exceptions, do not apply to defence-related claims and

- Schedule

17: contains some new definitions which are used in the Bill.

Development of statutory

compensation

Prior to 1900:

... the costs of work-related injury were overwhelmingly borne

by workers and their families. Access to compensation for work-related injury

was confined to common law remedies. At common law a worker could obtain

compensation if negligence was proven. The law, however, was judicially

constructed so as to prevent this.

At the heart of this predicament was a pernicious set of

legal doctrines known as the ‘unholy trinity’. These legal defences, devised by

English and American judges during the first half of the nineteenth century and

subsequently adopted in the Australian colonies, effectively quarantined

manufacturers and other employers from the consequences of their failure to

manage workplace health and safety.

The first of these defences, common employment, held that

employers were not legally accountable for injuries to any of their workers

caused by other members of their workforce. The second element, the voluntary

assumption of risk, reflected the prevailing view of contract law and held that

workers implicitly assumed responsibility for the normal hazards of their

employment. Under this doctrine, responsibility for workplace health and safety

was primarily, indeed almost exclusively, a matter for workers rather than

their employers. Finally, under the interpretation of contributory negligence

current at the time, employers were not liable for compensation where the

actions of workers themselves contributed, no matter how slightly, to their

injuries.

[Post 1900] ... state and federal governments introduced

workers’ compensation laws across the nation. These new laws were based on the

doctrine of no-fault liability. Under the no-fault principle, workers covered

by the legislation were only required to establish that their injuries were

work related in order to qualify for compensation. There was no obligation to

establish employer negligence.[10]

Nevertheless, under the early schemes described above, workers

could access their rights under common law in circumstances where the

employer’s negligence was so egregious as to override the effect of the unholy

trinity of defences.

No fault and limited

common law access

When the Commonwealth Employees’ Rehabilitation and

Compensation Bill 1988 (the precursor to the current SRC Act), was

introduced the Minister for Social Security, Brian Howe, said:

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the

new legislation is that common law actions against the Commonwealth will be

replaced by... comprehensive benefits ... It is clear to this Government that the

common law negligence action which bases its entitlement on proof of fault is a

costly, inefficient and inappropriate mechanism for compensating injured

workers. Delays in settling these actions act as a positive disincentive for

employees to return to work and encourage them to maximise the extent and

duration of their injuries. The provision of an adequate level of weekly

income, substantially increased lump sum payments on death or impairment,

payments for additional expenses for medical costs, aids and appliances and

household help, combined with a commitment to rehabilitation and the return to

suitable employment, make redundant any need for redress to the courts.

Accordingly, it will no longer be possible for an employee to sue the

Commonwealth or a fellow employee. Actions against third parties will also be

discouraged. Employees or their dependents who sue third parties will not be

entitled to receive further benefits under the scheme and will be required to

pay back any amount of compensation they have received. The Commission will

pursue third parties if necessary by taking over an action in place of the

employee.[11]

The Commonwealth Employees’ Rehabilitation and

Compensation Act 1988[12]

(when enacted) provided that an employee was entitled to claim compensation for

permanent impairment and/or non-economic loss. In the alternative, an employee

could elect to bring an action or proceeding against his, or her, employer or

another employee for damages. Such an election was irrevocable and if

successful, damages for non-economic loss were limited to $110,000.[13]

That provision remains unchanged today. The cap on damages in the SRC Act

has not been amended since it was introduced in 1988.

The trade-offs which were negotiated in 1988 are

undermined by the amendments in the Bill.

Who is covered by the Comcare

scheme

The SRC Act now underpins the Comcare scheme which

provides for the rehabilitation and compensation of injured employees employed

by:

- Commonwealth

Government agencies and statutory authorities that pay premiums to Comcare

under the SRC Act

- Australian

Capital Territory Government agencies and authorities that pay premiums to

Comcare under the SRC Act and

- Commonwealth

authorities and eligible corporations that have been granted self-insurance

licences by the Commission under the SRC Act.[14]

The groups covered by the first two bullet points above

are referred to as premium payers, whilst the group covered by the last of the

bullet points are referred to as licensees.

Current licensees

There are currently 33 licensees within the Comcare scheme.[15]

Rather than being a scheme to cover only public servants undertaking

administrative duties, the scheme now also covers employees undertaking a range

of job types in the telecommunications, building and construction and logistics

industries.

|

Asciano Services Pty Ltd

|

Australian air Express Pty Ltd

|

Australian Postal Corporation

|

|

Avanteos Pty Ltd

|

BWA Group Services Pty Limited (Bankwest)

|

BIS Industries Ltd

|

|

Border Express Pty Ltd

|

Colonial Services Pty Ltd

|

Commonwealth Bank of Australia Ltd

|

|

Commonwealth Insurance Ltd

|

Commonwealth Securities Ltd

|

CSL Ltd

|

|

DHL Supply Chain (Australia) Pty Ltd

|

Fleetmaster Services Pty Ltd

|

John Holland Group Pty Ltd

|

|

John Holland Pty Ltd

|

John Holland Rail Pty Ltd

|

K&S Freighters Pty Ltd

|

|

Linfox Australia Pty Ltd

|

Linfox Armaguard Pty Ltd

|

National Australia Bank Ltd

|

|

National Wealth Management Services Ltd

|

Medibank Health Solutions

|

Medibank Private Limited

|

|

Optus Administration Pty Ltd

|

Prosegur Australia Pty Ltd

|

Reserve Bank of Australia

|

|

StartTrack Retail Pty Ltd

|

Telstra Corporation

|

Thales Australia

|

|

TNT Australia Pty Ltd

|

Transpacific Industries Pty Ltd

|

Visionstream Pty Ltd

|

Administration of the Comcare

scheme

The Commission and Comcare are co-regulators of the SRC

Act.[16]

The SRC Act is administered by Comcare under the auspices of the

Commission. Broadly, Comcare provides safety, rehabilitation and compensation

services to the Commonwealth. The Commission oversees the activities of Comcare

and other service providers under the SRC Act. The rehabilitation and

compensation framework under the SRC Act and the work health and safety

requirements under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHS Act)

are together referred to as the Comcare scheme.

Comcare undertakes both regulatory

and claims management activities in relation to Commonwealth employees, in

accordance with the SRC Act and the WHS Act.[17]

The ongoing tension within the Comcare scheme is that employees who are injured

at work want to be appropriately compensated, whereas employers want ‘the

lowest possible workers’ compensation premiums and are concerned about the

escalating costs of work-related injuries and illnesses’.[18]

Reviews of the Comcare scheme

Since 2004, the Comcare scheme has been the subject of a

number of reviews including:

- by

the Productivity Commission in 2004: National Workers’

Compensation and Occupational Health and Safety Frameworks (Productivity Commission report)[19]

- by

the Commonwealth Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations in

2009: Report of the review of self-insurance arrangements under the Comcare

scheme (Review of self-insurance arrangements)[20]

which was prepared after receiving a report from consulting actuaries, Taylor

Fry[21]

- by

Dr Allan Hawke AC in 2012 in relation to the Comcare scheme’s performance,

especially its governance and financial frameworks (Hawke Report)[22]

and

- by

Peter Hanks QC in 2013 (Hanks Report).[23]

Together the Hawke and Hanks Reports are the SRC Act

Review reports. The SRC Act Review reports recommended sweeping change

with ‘more than 147 recommendations to rewrite the legislation on federal

public sector compensation claims with the aim of getting injured bureaucrats

back to work and ending their ‘‘passive’’ reliance on compensation’.[24]

The Bill puts many of those recommendations into effect.

The Hanks Report noted that there have been 59 Acts

amending the SRC Act since it was enacted in 1988. That being the case:

There is a strong case to be made for re-writing the SRC Act

in order to bring it up to date with current working conditions, to reflect

current best practices in rehabilitation and to ensure that it is laid out in a

logical and functional structure which is easy to follow and apply.[25]

Despite the introduction of this Bill and the previous two

Bills into the Parliament, the net result falls short of the rewrite of the SRC

Act which the Hanks Report suggested. Workers’ compensation is a type of

accident and injury insurance. The three Bills in their totality represent a

shift towards a national system which is intended to attract an increasing

number of employer corporations as licensees. If this occurs the SRC Act

will, in effect, set out the terms and conditions of the ‘insurance policy’ of

many more employees from a wider variety of occupations than it currently does.

In that case, all parties are deserving of a plain English statement of their

rights and obligations. The amendments to the SRC Act do not provide

that.

Senate Standing Committee on Education

and Employment

The Bill was referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Education

and Employment (Senate Committee) for inquiry and report.[26]

The Senate Committee tabled its report on 16 June 2015, recommending that the

Senate pass the Bill.[27]

The Labor members of the Senate Committee issued a

dissenting report recommending that the Senate reject the Bill.

We maintain that there exists no policy justification for

expanding self-insurance under Comcare (as per the changes suggested by the

Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Legislation Amendment Bill 2014), or

evidence of widespread misconduct or abuse of the system that would justify the

changes outlined in this Bill. Despite limited examples outlined in the Bill

(and on previous occasions by Coalition Senators) the report does not

demonstrate a compromise of the scheme, and Labor Senators argue the evidence

contained in the report only demonstrates the weight of opposition to the

amendments proposed by the Bill.[28]

In addition, the Australian Greens (the Greens) issued a

dissenting report recommending that the Bill not be passed stating that the

Bill:

... swings the balance too far towards employers at the expense

of employees making it even harder for workers with genuine claims to access

benefits and legitimate support.

As such the Bill represents a failure to implement genuine

reform, which should seek to improve the safety and health of workplaces.[29]

Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills

On 13 May 2015 the Senate Standing Committee for the

Scrutiny of Bills (Scrutiny of Bills Committee) published its comments in

relation to the Bill.[30]

Those comments are canvassed below under the heading ‘Key issues and

provisions’.

Parliamentary Joint Committee on

Human Rights

On 13 May 2015 the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human

Rights (the Human Rights Committee) published extensive comments in relation to

the Bill.[31]

The Human Rights Committee report is comprehensive, identifying numerous

provisions in the Bill which engage human rights. Comments by the Human Rights

Committee are canvassed under the heading ‘Key issues and provisions’, below.

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. Whilst

the Government acknowledges that some of the amendments in the Bill engage

human rights, it considers that the Bill is compatible.[32]

Labor members

Labor opposes the Bill.[33]

Speaking in relation to the Bill, Brendan O’Connor expressed his concern that whilst

the government relies upon the SRC Act Review reports in respect of a

number of changes:

This government has selectively adopted the recommendations

which benefit employers and has ignored the recommendations to benefit workers.

For example, the government has ignored the recommendations to include

contractors... to provide access to compensation when someone is injured on their

way to work, when on call, and for and injury management and rehabilitation

code of practice that includes obligations for employers.[34]

The opinions of major interest groups are sharply divided.

Those in favour of the Bill are generally employers and existing licensees.

For instance, Transpacific, a self-insurer in the scheme,

supports the amendments[35]

as does Australian airExpress, another self-insurer, which stated:

The package of change impacts many areas of the SRC Act and

in many instances are long overdue. AaE considers that the change package is

fair and equitable and balanced between the interest of employees and

employers. AaE supports that the whole package is passed to ensure the integrity

of this balance.[36]

Unions and workers’ representatives are less enthusiastic

about the Bill.[37]

The Australian Lawyers Alliance is ‘strongly opposed’ to the legislation ‘in

its entirety’ on the grounds that:

... the Bill has either ignored or entirely contradicted

recommendations put forward by Mr Hanks that ensured the fast and balanced

rehabilitation of workers back into the workforce. The proposed changes in the

Bill put the considerations of big business ahead of those of injured workers.[38]

As already stated the Victorian Government does not

support the Bill on the grounds that it will ‘create an exodus of premium

paying national employers from existing state/territory schemes, adversely

affecting existing pooling arrangements and premiums for medium to small

businesses in those jurisdictions’.[39]

Commentary by stakeholders in relation to the amendments

in specific schedules to the Bill is canvassed under the heading ‘Key issues

and provisions’ below.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum the Bill will have

nil financial impact on the Commonwealth.[40]

Whilst the Bill does not appear to increase the

Commonwealth’s costs, it will probably give rise to savings because the

premiums payable by Commonwealth departments are expected to decrease once the

amendments in the Bill, which limit an injured employee’s access to

compensation and the amount payable in the event that a claim is accepted, come

into effect.

Commencement

The provisions in Schedule 1 to the Bill commence on the

day after Royal Assent. The amendments in Schedule 1 apply in relation to any

injury which is sustained by an employee after that date.[41]

Definition of injury

Section 14 of the SRC Act provides that Comcare is

liable to pay compensation in accordance with the terms of the Act in respect

of an injury suffered by an employee, if the injury results in

death, incapacity for work, or impairment. Whether or not a claimant for

compensation has suffered an injury is a threshold question. If

the employee has not suffered an injury within the meaning set

out in the SRC Act, Comcare (or a self-insurer) has no liability to pay

compensation.

Currently, the definition of injury in

section 5A of the SRC Act means the following:

- a

disease suffered by an employee

- an

injury (other than a disease) suffered by an employee, that is a physical or

mental injury arising out of, or in the course of, the employee’s employment or

- an

aggravation of a physical or mental injury (other than a disease) suffered by

an employee (whether or not that injury arose out of, or in the course of, the

employee’s employment), that is an aggravation that arose out of, or in the

course of, that employment.

However, a disease, injury or aggravation suffered as a

result of reasonable administrative action taken in a reasonable

manner in respect of the employee’s employment is specifically excluded from

the definition.[42]

Guide to Schedule 1

The provisions in Schedule 1 to the Bill relate to an

employee’s eligibility for compensation and rehabilitation in respect of an

injury. They:

- widen

the scope of reasonable administrative action

- increase

the threshold for perception-based disease claims

- introduce

the term designated injury, for example heart attacks, strokes

and spinal disc ruptures, in relation to which the employee must prove the

connection with their employment rather than the current practice whereby

those injuries are considered to occur in the course of employment if they

occur in the workplace, and

- list

the matters to be taken into account in determining whether an ailment or

aggravation was contributed to, to a significant degree, by an employee’s

employment.

|

The Bill amends section 5A of the SRC Act to

substantially change what constitutes an injury.

Reasonable management action

First, references in section 5A of the SRC Act

to reasonable administrative action are replaced with references

to reasonable management action. Matters which are indicative of

the conduct which would be management action are listed in the

Bill.[43]

Management action is not unlike the current concept of

administrative action. However the amendment adds additional elements so that management

action will also include an organisational or corporate restructure, a

direction given for an operational purpose or purposes—and anything done in

connection with an action taken in either of those circumstances.

Key issue—establishing fault

Many submitters expressed dismay at the broadening of the

term administrative action to management action which will encompass ‘a

direction given for an operational purpose or purposes’. Slater and Gordon

considers that:

...the new provision will exclude injuries, including physical

injuries, that result from any operational direction given at any time prior to

the injury unless the direction is not reasonable ... Hence, an injury which has

been contributed to by a system of work may be excluded from compensation

unless the worker can establish that the system of work was not reasonable.

This introduces a concept of fault into a no-fault scheme and a perverse onus

of proof upon a faultless injured worker.[44]

The ACTU echoes these concerns stating:

Employers have an absolute duty of care to provide a safe

working environment, and workers’ compensation laws and processes must

acknowledge this duty of care and operate under the assumption that workers’

compensation is a no-fault jurisdiction.[45]

Anticipation or expectation of

management action

Second, the existing exclusion relating to reasonable

administrative action taken in a reasonable manner in respect of the employee’s

employment is amended.[46]

The amendment operates so that a disease, injury or aggravation suffered as a

result of an employee’s anticipation or expectation of reasonable management

action is also excluded from the definition of injury.

Designated injury

The third significant change is to introduce a new

class of injury—being a designated injury.[47]

A designated injury includes injuries such as heart attack,

stroke, an injury to an intervertebral disc and an injury which is prescribed

by regulations where the injury is not a disease and the injury consists of, is

caused by, results from, or is associated with a pre-existing ailment.[48]

If an employee suffers a designated injury

it will be for the employee to prove that his, or her, employment contributed

to the injury to a significant degree. In the absence of that proof Comcare, or

a self-insurer, will not be liable for compensation.[49]

The test for whether employment contributed to a designated injury to a

significant degree requires a consideration of matters such as the state of the

employee’s physical and psychological health before the designated injury and

the probability that, if the employee had not been employed in the employment,

the injury would have been suffered at or about the same time in the employee’s

life or at the same stage of the employee’s life.[50]

Key issue—intervertebral disc

The Law Council of Australia has expressed concern at the

specification of intervertebral disc injury as a designated injury

stating:

This is inconsistent with the approach in a number of other

jurisdictions, where such injuries are dealt with under ordinary liability

provisions. Normally there will need to be some environmental, as opposed to

congenital, contribution to an injury to an intervertebral disc. This is

distinguishable from a heart attack or a stroke which may simply occur due to

the natural progression of an underlying condition. There is no reason in

principle to deny liability for an injury to an intervertebral disc if it is

suffered because of an employee’s work duties.[51]

On the other hand, self-insurer Transpacific, broadly

supports the proposed exclusions from the definition of injury as

the ‘changes will bring the scheme into alignment with state based workers

compensation legislation’ and that ‘overall the proposed amendments under

Schedule 1 will greatly assist employers in reducing the burden of cost for

lifestyle and age related disease processes over which they have limited

control’.[52]

Definition of disease

At present, subsection 5B(1) of the SRC Act defines

disease as an ailment suffered by an employee (or

an aggravation of such an ailment) that was contributed to, to a significant

degree, by the employee’s employment by the Commonwealth or a licensee.

Subsection 5B(2) contains a list of matters which may be taken into account in

determining whether the ailment (or the aggravation of the

ailment) was contributed to, to a significant degree, by the employee’s

employment.

The Bill substantially changes what constitutes a disease.[53]

There are additional matters which may be taken into account in the

determination process, being:

- the

state of the employee’s physical and psychological health before the ailment or

aggravation[54]

- the

probability that the employee would have suffered from the ailment or

aggravation (or similar) at or about the same time in, or stage of, the employee’s

life[55]

- whether

the ailment or aggravation is, to a significant degree, attributable to the

employee’s belief about, or interpretation of an incident or state of

affairs—and if so, whether the employee had reasonable grounds for the belief

or interpretation.[56]

The latter of these amendments is a partial response to

recommendation 5.2 of the Hanks Report. [57]

According to Hanks ‘it is an unfair burden on employers to make them liable to

pay compensation for a psychological injury that is caused by an employee’s

fantasising rather than by any aspect of employment’.[58]

To that end he recommended that the effect of the Federal Court’s decision in Wiegand

v Comcare should be negated.[59]

The amendment does that. However, the remainder of the recommendation was that an

employee’s perception of a state of affairs will only provide a connection with

employment where that perception is reasonable. The amendment imposes a

stricter test—whether the employee has reasonable grounds for the belief.

In addition, the matters to be considered in making a

determination about whether an employee is suffering from a disease

will include any other matters affecting the employee’s physical or

psychological health and any other relevant matters.[60]

Key issue—a hypothetical assessment

According to the AMWU:

This proposal allows the determining authority to create a

“hypothetical case” where the authority has “insight” to be able to predict

what would or would not have happened. This particular provision will

discriminate against who have been active in both their working and

recreational lives. It’s hard to stop the ageing process![61]

The Australian Lawyers Alliance states that:

... despite a worker clearly suffering a work related injury,

an employer can shirk responsibility by contending that, because of his or her

age, they probably would have suffered the injury anyway. This test is clearly

intended to limit employers’ responsibility to rehabilitate and retrain the

older workforce.[62]

Compensation Standards

Finally, Comcare will be empowered to determine, by

legislative instrument, a Compensation Standard about a specified

ailment and to set out the factors that must exist before it can be said that a

person is suffering from it.[63]

Consistent with this power, where a Compensation

Standard is in force in relation to an ailment (or aggravation of an

ailment) the matters specified in the Compensation Standard must be taken into

account in the process of determining whether an employee has a disease.[64]

Human Rights Committee comments

The Human Rights Committee noted the tightening of the

eligibility criteria for accessing Comcare—particularly in respect of

designated injuries—and considered that ‘the measure engages and limits the

right to social security and the right to health’.[65]

Whilst the statement of compatibility indicated that the objective of the

measure is to re-align the SRC Act so that it better achieves its legitimate

purpose of compensating individuals for injuries and diseases that are related

to a person’s work, the Human Rights Committee has sought further advice from

the Minister for Employment in order to be satisfied that this is so.

Commencement

Schedule 2 contains four parts. Parts 1 and 4 commence on

day to be fixed by Proclamation, or 12 months after Royal Assent, whichever

comes first.

Part 2 commences on the later of the day immediately after

the commencement of the provisions in Part 1; or immediately after the

commencement of Schedule 2 to the Safety, Rehabilitation and

Compensation Legislation Amendment Act 2015.

Part 3 commences on the later of the day immediately after

the commencement of the provisions in Part 1; or immediately after the

commencement of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Safety, Rehabilitation and

Compensation Legislation Amendment (Exit Arrangements) Act 2015.

Guide to Schedule 2

The amendments in Schedule 2 to the Bill relate to who is

responsible for the rehabilitation of an employee, and how that

rehabilitation is carried out. Schedule 2:

- introduces

the concept of liable employer and sets out the duties of

liable employers

- amends

the definition of suitable employment to mean any employment

including self-employment

- establishes

the Comcare incentive scheme

- amends

the existing two stage process for creating a rehabilitation program to a

single stage process for formulating workplace rehabilitation plans

- introduces

the requirement that an employee undergo a work readiness assessment

if there is doubt about the employee’s capacity for suitable work and

- inserts

a power for an employer to require an employee to undergo a medical

examination by a medical practitioner who is chosen by the employer.

|

Liable employer

The Bill amends Part III of the SRC Act in order to

identify the employer that is responsible for the rehabilitation of the employee.[66]

In most cases the employer will be the current

employer.[67]

To this end, the definition of current employer is inserted into

subsection 4(1) of the SRC Act as follows:

(a) if the

employee is employed in an Entity—the principal officer of the Entity[68]

or

(b) if the

employee is employed in a Commonwealth authority—the principal officer of the

Commonwealth authority or

(c) if the

employee is employed by a licensed corporation—the principal officer of the

corporation or

(d) if the

employee is employed by a corporation (within the meaning of Part VIII)

that is not a licensed corporation—the principal executive officer of the

corporation.[69]

However, where the injury is a disease, a designated

injury or an aggravation of a designated injury, the liable

employer will be the person’s employer at the time that the employment

contributed, to a significant degree, to the disease, designated

injury or the aggravation of a designated injury.[70]

The exception to the rules about identifying the liable

employer is if the employer is an exempt authority.[71]

In that case, the liable employer will be Comcare.

In addition, where employment with two or more liable

employers contributed to a disease, a designated injury or

an aggravation of a designated injury the most recent employer is

the liable employer.[72]

The Bill sets out the default position in circumstances where the liable

employer ceases to exist or ceases to perform a function.[73]

For the avoidance of doubt, Comcare may determine a specified Entity or

Commonwealth authority to be the liable employer. In that case, Comcare must

notify the employee in writing of that determination.[74]

Duties of liable employers

The Bill sets out the duties of liable employers being:

- the

duty to ensure the rehabilitation of the employee and

- the

duty to provide suitable employment.[75]

The first duty arises when a liable employer has

been formally notified of an injury suffered by an employee which results in an

incapacity to work or an impairment.[76]

The liable employer must take all reasonably practicable steps to ensure the

rehabilitation of the employee.[77]

Section 4 of the SRC Act defines impairment as the loss,

the loss of the use, or the damage or malfunction, of any part of the body or

of any bodily system or function, or part of such system or function.

In the event that an employee has suffered an injury

resulting in an incapacity for work, or an impairment, the second duty

of a liable employer is to take all reasonably practicable steps to provide the

employee with suitable employment or assist the employee to find such

employment.[78]

In order to fulfil the second duty the liable employer must first determine

whether the employee has the potential to be in suitable employment.

That must be ascertained having regard to the potential of the employee to be

rehabilitated, to benefit from medical treatment and any other relevant

matters.[79]

The second duty operates so that if the injured or

incapacitated employee is in suitable employment, the liable employer must take

all reasonably practicable steps to maintain the employee in suitable

employment.[80]

The liable employer, in performing the duty to provide

suitable employment, is required as far as reasonably practicable to consult with

both the employee and the legally qualified medical practitioner who is

providing, or supervising, the medical treatment for the injury.[81]

In that case, the medical practitioner may give the liable employer information

about the employee that is relevant to the consultation.

Suitable employment

Suitable employment means any employment

(including self‑employment) for which the employee is suited, having

regard to:

- the

employee’s age, experience, training, language and other skills

- the

employee’s suitability for rehabilitation or vocational retraining

- if

employment is available at a place that would require the employee to change

his or her place of residence—whether it is reasonable to expect the employee

to change his or her place of residence and

- any

other relevant matters.[82]

According to the Hanks Report, some participants in the

consultations which were part of the review process argued that the definition

of suitable employment should not be limited to the existing employer ‘because

return to work in the same workplace can be difficult and is not optimal in all

cases. There is no support provided in the Comcare scheme for a return to work

with a different employer’.[83]

The expanded definition of suitable employment responds to

this concern by providing that suitable employment may mean any employment

including self-employment. In addition, Comcare is empowered by the Bill to

formulate a scheme which would allow Comcare to make payments to employers as

an incentive to provide suitable employment for employees who have suffered an

injury, are unemployed and are seeking paid work.[84]

This responds to recommendation 6.18 of the Hanks Report.[85]

However the expanded definition of suitable work dovetails

with the ‘deemed capacity to earn’ provisions which are contained in Schedule 9

to the Bill. This will have an impact on the rate at which weekly incapacity payments

are made ‘even where the worker is not working’.[86]

(See the discussion under Schedule 9 below.)

Workplace rehabilitation plans

The Hanks Report recommended that the term ‘rehabilitation

program’ in the SRC Act should be changed to ‘workplace rehabilitation

plan’ on the ground that the ‘title would confirm that rehabilitation is

vocationally directed and is aimed at the return to work of the employee’.[87]

It is through the introduction of workplace rehabilitation plans and the

obligations which arise for an employee under them, that the Bill moves the

core emphasis of rehabilitation from a medical focus to a return to work focus.

Employer’s obligations

Consistent with the employer’s first duty—to ensure the

rehabilitation of the employee—a liable employer who has been formally notified

of an injury must consider whether there should be a workplace

rehabilitation plan, and if so, the content of the plan.[88]

If there is to be a workplace rehabilitation plan it

is the liable employer’s role to formulate it. It is not the employee’s role

and it is not the role of their medical practitioner.[89]

However, before doing so, the liable employer must, as far as reasonably

practicable, consult all of the following:

- the

employee

- the

legally qualified medical practitioner who is providing, or supervising, the medical

treatment of the injury and

- if

the liable employer is not the current employer of the employee—the current

employer.

As part of that consultation, both the medical

practitioner and the current employer (if relevant) may give the liable

employer relevant information about the employee.[90]

If the liable employer decides to formulate a workplace

rehabilitation plan for an employee, then a copy is to be given to the

employee and the employee is to be informed of his, or her, responsibilities

under the plan.[91]

If the liable employer is not the current employer, the liable employer must

give a copy of the workplace rehabilitation plan to the current

employer[92]

who must, as far as reasonably practicable, cooperate with the liable employer

in relation to the plan and take all reasonable steps to allow the employee to

fulfil his, or her, responsibilities under the plan.[93]

Importantly, a liable employer may decide not to formulate

a workplace rehabilitation plan for an employee in relation to an injury. The

Explanatory Memorandum is silent about the circumstances in which a liable

employer would not formulate a workplace rehabilitation plan. Presumably this

would only occur where the employee has suffered a catastrophic injury. However,

the Bill does not specify the matters to be taken into account by an employer

in making the decision not to formulate the relevant plan. However, the liable

employer must notify the employee in writing of that decision.[94]

A liable employer may, in writing, vary or revoke the plan

at any time.[95]

Before that occurs, the employer must consult with the employee and the legally

qualified medical practitioner who is providing, or supervising, the medical

treatment of the injury.[96]

If the plan is varied, the liable employer must give a copy of the variation or

revocation to the employee, the current employer (if that is not the liable

employer) and to the relevant authority.[97]

It may be that a workplace rehabilitation plan

provides that specified activities are to be carried out by the liable employer

under the plan. In that case, the liable employer must comply with the plan, to

the extent that the plan imposes obligations on the employer.[98]

Content of the workplace

rehabilitation plan

A workplace rehabilitation plan is directed

towards returning the employee to suitable employment as soon as practicable

and, that done, in maintaining the employee in suitable employment.[99]

If the employee does not have the potential to be in suitable employment, the workplace

rehabilitation plan is directed towards maximising the employee’s

independent functioning.

A workplace rehabilitation plan may make provision

for a range of activities including, but not limited to, any or all of the

following:

- an

initial rehabilitation assessment, a functional assessment and/or workplace

assessment[100]

- advice

about job modification[101]

- job

seeking, in addition to training in relation to and advice or assistance about

job seeking[102]

- the

provision of aids, appliances, apparatus or other material that is necessary to

facilitate return to work or maintaining the employee in work[103]

and

- modification

of a work station or equipment used by the employee in order to facilitate

return to work or maintaining the employee in work.[104]

Employee’s obligations

The employee has three sets of obligations.

First an employee must participate in the

consultation with the employer about the content of the workplace

rehabilitation plan[105]—even

though a failure to do so will not affect its validity.[106]

The second obligation (known as the employee’s

responsibilities) is to undertake the specified activities that are set

out in the workplace rehabilitation plan.[107]

This responsibility is particularly onerous. Even if the employee does not

agree with the contents of the workplace rehabilitation plan, a refusal or failure, without reasonable excuse, to

fulfil his, or her, stated responsibilities under a workplace rehabilitation

plan will lead to the imposition of sanctions on the employee.[108]

These sanctions include suspension of payments of weekly compensation until the

breach is remedied and, in the most serious of cases, cancellation of the

employee’s entitlement to workers’ compensation. (See the discussion about the

sanctions regime under Schedule 15 below.)

Finally, where the workplace rehabilitation plan provides

that one or more job‑seeking activities are to be carried out by the

employee, the employee must notify the liable employer, in writing, of any

change to the employee’s circumstances that would affect the employee’s ability

to carry out those activities within three working days, after the employee

becomes aware of the change.[109]

Review rights

Where a liable employer is the principal officer of a licensed

corporation and has formulated a workplace rehabilitation plan (or has decided

not to formulate workplace rehabilitation plan), the employee must be given a written

notice setting out the terms of the determination and the reasons for it, along

with a statement that the employee may request the relevant authority to

conduct a review of the determination.[110]

The request for a review must be made within 30 days after

the day on which the determination first came to the notice of the employee or within

such further period (if any) as the relevant authority, either before or after

the expiration of that period, allows.[111]

The relevant authority must review the determination and

may make a decision affirming or revoking the determination or varying the

determination in such manner as the relevant authority thinks fit.[112]

Key issue—achieving return to work

outcomes

According to the Australian Public Service Commission:

... there is strong international evidence that injured workers

will get sicker if they remain at home. Historical

thinking was that injured employees should be at home until they are 100

per cent job ready. Current evidence is that the interests of employees are

best served if they return to work as soon as possible, with workplace

adjustments to support their return ...

Return-to-work rates are falling in the APS, from

approximately 89% in 2008-09, to 80% in 2012-13. Changes to the scheme which

improve the return-to-work process are critical, given the strong evidence of

the health benefits of work.[113]

However there is concern that workplace rehabilitation

plans may include job seeking activities. Slater and Gordon argues that the

Bill:

... significantly broadens the concept of suitable employment

and provides the liable employer with the power to order an employee to carry

out one or more job seeking activities. Rather than being limited to the liable

employer who is responsible for the injury, suitable employment includes any

job with any employer. This means liable employers can divest themselves of

responsibility to provide suitable employment by passing the injured worker off

to the job market at large, whether or not that market realistically has a job

for the worker.[114]

The rationale for the amendment lies in the Hanks Report,

which states:

It can be difficult to maintain rehabilitation momentum for

an injured employee who has received incapacity payments for a significant

period. In order to maintain momentum for long-term incapacitated employees,

examination of the model used by Centrelink, in particular the activity test,

may be useful.

(a) The

activity test is designed to ensure that unemployed people receiving income

support payments are “actively looking for work and/or doing everything that

they can to become ready for work in the future”.

(b) Similarly,

participation requirements “aim to ensure that a person looks for, and

undertakes, paid work in line with the person’s work capacity” in order “to

increase work force participation ... and reduce welfare dependency”.

(c) Generally,

job seekers must be “actively seeking and willing to undertake any paid work

that is not unsuitable”. That usually requires job search, paid or voluntary

work, study or other activities. Different requirements may apply for job

seekers who have a partial capacity to work, early school leavers, those who

are principal carers, and those aged 55 or over.

(d) A person

who does not meet the activity test or participation requirements may have a

“failure” imposed, which may affect the person’s social security payments.[115]

The amendment institutes an activity test element into the

workplace rehabilitation plan as suggested by the Hanks Report. However the Hanks

Report recommended that an activity test be introduced only where the injured

employee has received incapacity payment for a significant period. The Bill

does not include that limitation and provides that an activity test may be part

of a workplace rehabilitation plan.

There is nothing in the drafting of the Bill which would

moderate the power of an employer to formulate a workplace rehabilitation plan

requiring an injured employee to undertake job seeking activities at any time.

In formulating the workplace assessment plan the employer must, as far as

reasonably practicable, consult with the employee’s medical practitioner. However,

there is no obligation upon an employer to accept the opinion of the medical

practitioner. In addition, as can be seen below, there is no requirement that

an injured employee undergo a work readiness assessment. It is merely one of a

number of tools at the disposal of the liable employer to achieve a return to

work outcome.

Work readiness assessment

The relevant authority may require an

injured employee to undergo an assessment of the employee’s capacity to

undertake suitable employment. This is known as a work readiness

assessment.[116]

A work readiness assessment must be made by any of the following

who are nominated by the relevant authority:

- a

legally qualified medical practitioner

- suitably

qualified person—other than a legally qualified medical practitioner or

- a

panel comprising of such legally qualified medical practitioners or other

suitably qualified persons (or both).

The person who conducted the work readiness assessment

must give a report of the assessment to the relevant authority. That report

must be in accordance with the rules (if any) about such reports that have been

made by Comcare.[117]

Power to require medical

examination

Currently, subsection 57(1) of the SRC Act empowers

the relevant authority to require an employee who has given notice of an

injury, or made a claim for compensation to undergo a medical examination by a

legally qualified medical practitioner nominated by the relevant authority.

That subsection is amended by the Bill so that, in

addition to the existing power to require an employee to undergo a medical

examination, an examination may be required where one or more payments of compensation

are being made to an employee under the SRC Act.[118]

The relevant authority may require the employee to undergo an examination by

any of the following who are nominated by the relevant authority:

- a

legally qualified medical practitioner

- a

suitably qualified person—other than a medical practitioner or

- a

panel comprising such legally qualified medical practitioners or other suitably

qualified persons (or both).

If an employee undergoes such a medical examination, a

report of the examination must be given to the relevant authority. In that

case, if the relevant authority is not the liable employer, the relevant

authority may give a copy of a report of the examination to the liable

employer. The report of the examination may be used by the liable employer in

the exercise of the powers, or the performance of the functions, of the liable

employer under Part III of the SRC Act—that is for rehabilitation.[119]

Key issue—review of ongoing

entitlement

The Hanks Report states:

The literature is clear. The majority of injured employees

make full physical, mental and social recoveries, but there is much individual

variation. Around 20 % to 30 % suffer significantly greater distress and

disability than might be expected from physical factors alone. After one year,

approximately 5 % of employees encounter serious difficulties which appear out

of proportion to the physical pathology of their injuries.

There is no legislative impediment to a determining authority

conducting a review at any point during the life of a claim. One of the

functions of determining authorities is to minimise the duration and severity

of injuries to employees.[120]

The Hanks Report recommended that there be a review of

each claim at predetermined times. The amendment to subsection 57(1) of the SRC

Act above, falls short of imposing the formal reviews which were

recommended. However, it will allow the relevant authority to request that an

employee undergo a medical examination at any time once the claim has been made,

the outcome of which will identify any additional factors to be addressed in

the employee’s ongoing recovery and rehabilitation.

Commencement

Schedule 3 comprises three parts. Parts 1 and 3 commence on

the day after Royal Assent.

Part 2 commences immediately after the commencement of Part

1; or immediately after the commencement of Schedule 2 to the Safety,

Rehabilitation and Compensation Legislation Amendment Act 2015—whichever is

later.

Guide to Schedule 3

Schedule 3 to the Bill contains a mix of amendments which

are intended to improve the integrity and financial viability of the Comcare

scheme which span different Parts of the SRC Act including:

- existing

provisions about third party indemnity in common law claims (Part IV)

- passing

a claim for compensation to the relevant authority within three days and

requesting information for the purpose of assessing a claim (Part V)

- imposing

time limits for considering claims and reconsidering claim determinations

(Part VI)

- establishing

that compensation for detriment may be paid in the event of defective

administration (Part VII)

- granting

licences (Part VIII) and

- recovery

of overpayments (Part IX).

|

Common law claims against third

parties

Existing section 50 (contained in Part IV) of the SRC

Act provides that a compensation payer can recover damages from a liable

third party where the injured employee or a dependant of a deceased employee

can recover damages. In that case Comcare can make a claim against the liable

third party in the name of the employee or dependant for the recovery of

damages.

Under the Bill, third parties will be required to

indemnify compensation payers where there exists both an obligation to pay

compensation under the SRC Act and an undischarged liability on the part

of a third party to pay damages or state compensation.[121]

Claims for compensation

At present section 54 (contained in Part V) of the SRC

Act provides that compensation is not payable to a person under the Act

unless a claim for compensation is made by, or on behalf of, the person. Under

the Bill, where an employee gives a claim to the Entity or Commonwealth

authority in which the person was employed at the time the injury occurred, the

Entity or authority must ensure that the claim is given to the relevant

authority within three working days after the day on which the claim was

received.[122]

Power to request information

At present section 58 of the SRC Act contains a power

to request the provision of information.[123]

The Bill amends that power so that where a relevant authority has received a

claim and is satisfied that the claimant either has information or a document

that is relevant to the claim or could obtain such information or a copy of the

document—without unreasonable expense or inconvenience—then the relevant

authority may give written notice to the claimant requiring the claimant to

give the information or documents to the relevant authority in the time and

manner which is set out in the notice. The period for compliance must not be

less than 14 days after the notice is given.[124]

If a claimant refuses or fails, without reasonable excuse,

to comply with such a notice, the relevant authority may refuse to deal with

the claim until the claimant gives the relevant authority the information, or a

copy of the document, specified in the notice.[125]

Where a relevant authority has

received a claim and is satisfied that a third party has information or a

document or could obtain such information or a copy of the document—without

unreasonable expense or inconvenience—the relevant authority may give written notice

to the third party requesting him or her to give the information or documents

to the relevant authority in the time and manner which is set out in the

notice.[126]

The period for compliance must not be less than 14 days after the notice is

given.

If the third party complies with a notice given by a

relevant authority, an amount may be paid to the person, in relation to

compliance with the notice, by the relevant authority.

Key issue—loss of privacy

According to the Australian Lawyers Alliance:

No other workers’ compensation scheme provides for such a

broad and unrestrictive provision of private medical information. The private

rights of individuals to consultation and treatment are being eroded by these

provisions without justification. Workers may be obliged to disclose highly

confidential and sensitive information irrelevant to the workers compensation issues

in dispute. That information can be used for a variety of purposes to the detriment

of the injured worker without adequate protection checks and balances.

[These changes] now enable Comcare and licensees to force an

injured worker or claimant to obtain their doctor’s private clinical notes. A

worker must obtain “relevant information” or risk draconian sanctions being

applied which, in this case, extends to a refusal to deal with a claim.

These changes represent an erosion of the doctor-patient

relationship of confidentiality.[127]

Slater and Gordon agrees. ‘New section 58 of the Bill

introduces a disturbing invasion of the right to privacy of an injured worker.

[It] enables Comcare or a “relevant authority” to demand information from a

worker within 14 days.’[128]

Of additional concern to Slater and Gordon is that:

No appeal mechanism follows where there is a genuine dispute

in relation to whether certain information or a certain document is actually

relevant to a claim. This is particularly important where information requests

are worded broadly and would require an injured worker to provide private and

potentially irrelevant medical information to the relevant authority in whose

hands privacy would not be guaranteed ...

The new section 58A takes the breach of privacy one step

further in that it enables Comcare or the relevant authority to obtain

documents about an injured worker from a third party.[129]

Time limits for determining claims

Currently subsection 61(1A) (contained in Part VI) of the SRC

Act provides that a determining authority must consider and determine each

claim for compensation under section 14 within the period prescribed by the

regulations. However, no such regulations have been made. Instead the SRC

Act requires Comcare to make determinations accurately and quickly in

relation to claims.[130]

Where a licence confers an authority to pay claims, licensees are to do

likewise.[131]

The Bill inserts time limits within which compensation

claims are to be determined. The amendments operate as follows:

- Where

the claim for compensation is for an injury that is not a disease, a

designated injury or an aggravation of a designated injury—liability under

section 14 in respect of the claim is to be determined within the 30‑day

period that began when the claim was received.[132]

Where such liability is not determined within the 30‑day period, the

determining authority is taken to have made a determination that compensation

is not payable.[133]

- Where

the claim for compensation relates to an injury that is a disease, a

designated injury or an aggravation of a designated injury—the determining

authority must consider and determine the claim, to the extent that the claim

relates to liability under section 14, within the 70‑day period that

began when the claim was received.[134]

Where such liability is not determined within the 70‑day period, the

determining authority is taken to have made a determination that compensation

is not payable.[135]

Whilst it is an improvement on the existing Comcare scheme

that time limits for determining a claim have now been inserted those time

limits are, in most cases, longer than time limits in state schemes.

|

Jurisdiction

|

Timeframes for claim decision

|

|

Queensland

|

Workers’

Compensation and Rehabilitation Act 2003

Subsection

134(2) requires an insurer to make a decision on an application for

compensation within 20 business days after the application is made. If a

decision is not made within that time, the insurer must, within five business

days, notify the claimant of his or her rights of review.

|

|

New South Wales

|

Workplace

Injury Management and Workers Compensation Act 1998

Under sections

275 and 280

an insurer must provisionally accept liability within seven days after

notification of injury for up to $5,000 of medical payments.

A decision on ongoing liability for weekly payments must

be made within 21 days of a claim, under subsections

274(1) and 279(1).

|

|

Victoria

|

Workplace

Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013

28

days for weekly payments if the claim is received by the insurer within ten

days of the date of the injury.

|

|

Tasmania

|

Workers’

Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988

Section 81AB and subsection 81A(1) operate so that an

employer has 84 days to dispute liability in respect of a claim.

|

|

South Australia

|

Return

to Work Act 2014

Subsection

31(4) provides that where the claim is for income maintenance, it is to

be determined, where practicable, within ten business days after the date of

receipt of the claim.

|

|

Western Australia

|

Workers’

Compensation and Injury Management Act 1981

Subsection

57A(3) provides that the insurer must, before the expiration of

14 days after the claim was made by the employer give the worker to whom

the claim relates, and the employer, notice that liability is accepted or

that liability is disputed.

|

Source: Safe Work Australia, Comparison

of workers’ compensation arrangements in Australia and New Zealand (2015),

Commonwealth of Australia, July 2015.

Time limits for reconsideration

Existing section 62 of the SRC Act allows for a

determining authority to reconsider a determination on its own motion or at the

request of a claimant, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth authority. Subsection

62(6) provides that the reconsideration of a determination must be made ‘within

the period prescribed by regulations’. The Bill will require that a determining

authority must decide the request for consideration within the 60‑day

period that began when the request was received. In the event that this does

not occur, the determining authority is taken to have made a decision affirming

the determination.[136]

Under existing section 63 of the SRC Act, the

reconsideration decision is a reviewable decision.

Applications to the Administrative

Appeals Tribunal

Existing subsection 64(1) of the SRC Act sets out the

parties who are entitled to make an application to the Administrative Appeals

Tribunal (AAT) for a review of a reviewable decision.

The Bill amends section 64 of the SRC Act so that

where an application has been made to the AAT for review of a decision that was

made under section 62, the parties may agree that a specified determination

should be treated as a reviewable decision. In that case the two decisions can

be considered together, provided that they relate to the same employee and the

same issue, incident or state of affairs.[137]

Compensation for detriment caused

by defective administration

The Bill contains provisions which will allow for the

payment of compensation for detriment caused by defective administration as

follows:[138]

- Comcare

will be empowered to make payments to persons who are, or were, entitled to

compensation under the SRC Act and who have suffered a loss as a result

of an act or omission of Comcare that relates to that compensation

and concerns Comcare’s claims management functions or powers

- in

deciding to make a payment under the section, Comcare must comply with any

principles determined by the Minister, by legislative instrument

- the

particulars of a payment made under the section must be included in Comcare’s annual

report prepared by the Chief Executive Officer and given to the Minister under

section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act

2013.[139]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, this places

Comcare in the same position as other non-corporate Commonwealth entities.[140]

However, the payment of compensation under the proposed provision does not

extend to a licensee.

Scrutiny of Bills Committee

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee drew attention to item

1 of Schedule 3 of the Bill, which has the effect of excluding

decisions made about compensation for detriment caused by defective

administration from being reviewed under the Administrative Decisions

(Judicial Review) Act 1977 (the ADJR Act).[141] Despite the Explanatory Memorandum

and statement of compatibility suggesting that this approach is justified for a

number of reasons, the Scrutiny of Bills Committee stated that:

As a matter of general principle, the committee does not

accept the broad proposition that judicial review should not be available in

relation to discretionary schemes for compensation, and remains unpersuaded as