03/02/2023

The Australian system of government is notoriously difficult to categorise. Although based upon the Westminster tradition, the unique role of the Australian Senate means that our parliamentary system cannot be described as purely ‘Westminster’.

On Friday 10 February, Dr Marija Taflaga will present a Senate Lecture exploring the merits of an alternate descriptor of the Australian system: semi-parliamentarianism. Dr Taflaga’s lecture will outline how this concept may assist us in understanding how Australian politics are practised.

The Australian Senate and the Westminster tradition

While the Australian system of government is often described as a Westminster system, this is not the full story.

As former Clerk of the Senate Harry Evans, remarked:

[It is a misconception] that Australia was intended to have a system of government basically similar to that of the United Kingdom. This misconception is embodied in the frequently heard statement that we have a ‘Westminster system’. On the contrary, the framers of the Constitution explicitly and deliberately departed from the British model.

Former Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Harris, observed that participants in the 1890s constitutional conventions took considerable inspiration from the Westminster tradition, however:

there was a quite conscious global search to identify the most appropriate elements of other systems of government for the new nation.

These innovations mean that the Australian system functions quite differently to the British model.

Australia’s most significant departure from the British model is the status of the Australian Senate as an elected body with powers virtually equal to those of the House of Representatives. In this case, the framers were influenced by the Constitution of the United States, which established a Senate which was composed of an equal number of representatives from each state.

Delegates from the smaller colonies at the constitutional conventions would not countenance a system which gave the Senate only a delaying role or very limited powers in relation to financial legislation, similar to that of the British House of Lords. As Frederick Holder from South Australia stated at the 1897 convention in Adelaide:

To set up a Senate which will have no power of the purse will be to set up an absolutely worthless body.

In other countries with political systems based on the Westminster model, upper houses much closer in nature to the House of Lords emerged. For example, Canada has only one elected house and members of the Canadian Senate are directly appointed by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister. In New Zealand a similar system to the Canadian one operated until the upper house was abolished in 1951.

Implications for the role of the Senate

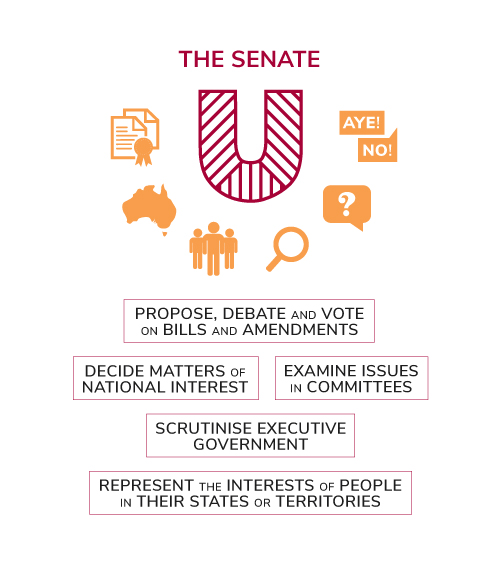

Role of the Senate (Photo: PEO)

The significant powers given to the Senate under the Constitution, coupled with its proportional system of voting which makes it difficult for a major party to secure control, has enabled the Senate to operate effectively as a house of review. The Senate regularly uses its powers to hold the government to account, including by conducing inquiries into government administration and ordering the government to produce information.

Further discussion of the Senate's accountability and review functions are outlined in previous Senate matters articles and Senate Lectures.

To learn more about the concept of semi-parliamentarianism, the role of the Senate and how our system of government can be categorised, please join us at Australian Parliament House or online at 12.15 pm on 10 February 2023 for the next Senate Lecture. For more information about the lecture, or to register, visit aph.gov.au/senate/lectures.

Further reading: