Papers on Parliament No. 60

March 2014

Michael Maley "International Election Observation: Coming Ready or Not*"

Prev | Contents | Next

Introduction

International election observation has become so entrenched an element of the democratisation process in the last 25 years that we are now relatively used to seeing media coverage of the activities of, or assessments made by, international observers. The work done in support of democracy by one of the most prominent of their number, President Jimmy Carter, was cited as one of the reasons for the award to him of the Nobel Peace Prize of 2002.

In association with this growth, much has been done with the aim of making observation more systematic, professional and reliable.[1] At its best, participation in election observation can be an extraordinarily exhilarating experience. Observers often see critical moments in history unfolding before their eyes, as in South Africa in 1994; and the joy displayed by people who are exercising their democratic rights for the first time is something that stays with you for the rest of your life, if you care about such things.

At its worst, however, election observation may be the moment when you see people's hopes thrown into doubt or dashed; and when you, as an observer, are suddenly placed in a unique situation of responsibility to tell the truth to the world on their behalf. There was a spectacular example of this only a couple of months ago, in Azerbaijan.

In Australia, we have never experienced judgemental international observation of our elections, though election administrators from friendly foreign counterparts of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) have since 1996 been coming here regularly to take part in structured election visitor programs.

Australia has, however, engaged quite actively in the observation of elections in our region, in neighbouring countries such as Indonesia, East Timor, Solomon Islands and Cambodia. In some cases the delegations in question were formally deployed by the Commonwealth Parliament; and two of our recent foreign ministers have served as election observers. Australians have also taken part in election observation operations mounted further afield by international organisations such as the United Nations and the Commonwealth Secretariat, in places including Namibia, Cambodia, South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Kenya and Sierra Leone. I had the good fortune to be involved in a number of these operations; and in some other cases, I briefed the participants before they left our shores. Invariably, it was clear that the observers understood that they were doing something really important, which would be a memorable moment in their careers.

Election observation is now a massive field of endeavour. In recent decades dozens of international bodies have deployed thousands of observers to hundreds of elections. Associated with observation, a significant literature has developed, not just on the process in general but also on specific aspects of its implementation, such as the concept of 'free and fair elections'.[2] Rare indeed is the individual whose personal experience can cover even a substantial fraction of this activity; and I certainly would not claim to be such a person. What I am going to discuss here therefore very much reflects my own, possibly idiosyncratic, perspective on this topic; and other experts in the field, whose views I greatly respect, might well reach different conclusions. My aim here is to provoke thought, not to provide definitive answers.

The balance of my paper today falls into three broad parts:

- First, I want to provide you with some background information about the observation process: examining how it is defined; outlining the standards which are applied to or by observers; and discussing observers' typical activities.

- Having done that, I will move on to a discussion of the broader context in which observation takes place, from the point of view both of the target country, and of the observers themselves.

- Finally, I will flag some of the present and looming challenges to which the observation process gives rise.

In the course of this discussion, I will be touching at a number of points on some other questions:

- Does observation always live up to expectations?

- Can it sometimes be damaging rather than beneficial?

- What lessons have been learned, and how have approaches to observation changed?

- What (if anything) do international observers contribute that local observers cannot?

Definition of 'election observation'

In one sense, of course, every voter, candidate, party worker, journalist, etc. is an election observer: he or she participates in, and therefore 'observes', at least part of the election process. My focus, however, is on something narrower, of which the following is a widely accepted definition:

the systematic, comprehensive and accurate gathering of information concerning the laws, processes and institutions related to the conduct of elections and other factors concerning the overall electoral environment; the impartial and professional analysis of such information; and the drawing of conclusions about the character of electoral processes based on the highest standards for accuracy of information and impartiality of analysis.[3]

The key elements of this are its emphasis on a systematic and comprehensive approach; the priority which has to be given to impartiality and accuracy; and the fact that observation is an inherently judgemental activity. Implied, though not explicitly stated, is the notion that observers stand apart from the election process, and have absolutely no right to intervene in it.[4]

An important point to flag here is that an election process is an especially intimate part of the exercise by a nation of its sovereignty. International election observation is only ever undertaken at the invitation of the country holding the election (though this 'invitation' may be a standing one flowing from international commitments, as in the case of participating countries of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)-from whence flows the reference in the title of this paper to observers 'coming ready or not'). Assessment of elections by foreigners is therefore an inherently delicate process, which can sometimes present observers with possible conflicts of interest at the personal, organisational, or even national levels.

Sources of standards

Election observers typically have to come to terms with two different types of standards.

First, there are those that govern their own behaviour by defining what constitutes the proper and professional performance of their tasks. These can come from a range of different sources. Very often, host countries will set out expected standards of behaviour, either in the electoral law, or in a code of conduct for observers. International discussions over the years have also led to the promulgation of generic codes of conduct.[5] At the heart of virtually all such documents are the following five key ethical principles:

- Election observers must recognise and respect the sovereignty of the host country.

- Election observers must be non-partisan and neutral.

- Election observers must be comprehensive in their review of the election, considering all relevant circumstances.

- Election observation must be transparent.

- Election observation must be accurate.[6]

Secondly, there need to be standards by which observers can assess elections: any objective and credible process of judgement and evaluation must have at its heart a defined set of criteria which enable good processes to be distinguished from bad ones. There have tended to be two main approaches to this.

The first has been to expect that an election should be 'free and fair'. For this time-honoured expression to be useful in practice, it needs to be given substance and content. One still sometimes hears it said that the concept of 'free and fair' elections is a vague and ill-defined one, but in fact a good deal of energy has been devoted in the last 25 years to defining the concept, on the whole successfully. On 26 March 1994, the Inter-Parliamentary Council of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) adopted a Declaration on Criteria for Free and Fair Elections which has become a bedrock document in this area.[7] The IPU has since sponsored a number of detailed studies of the international law and practice surrounding free and fair elections, and the concept has also been given close attention by scholars.[8] Broadly speaking, it can be said that an election will be free and fair if the following tests are met:

- The election is administered impartially, and opportunities exist for complaints about the process to be lodged and dealt with in an even-handed and transparent way.

- People qualified to vote, and only people so qualified, are able to do so.

- They can vote in an open and neutral political environment where contending views can be safely expressed in an election campaign.

- Votes are not bought and sold.

- Voters can cast a secret ballot, without fear of any adverse consequences.

- Everyone votes only once.

- They know the nature and significance of the act of voting.

- Their votes are counted and tabulated accurately, without any fraudulent interference.

In practice, these criteria will typically be elaborated into more detailed performance benchmarks relevant to the circumstances of a particular election.

One sometimes hears these criteria for a free and fair election described as 'aspirational', the implication being that it would be unreasonable to judge too harshly a country, especially a poor country, which fails to satisfy them. I would have to say that I flatly disagree with that perspective.

Taken as a whole, the criteria represent little more than a minimalist statement of requirements which normally need to be met in order to ensure that an election represents a genuine expression of the will of the people of the country. Except in unusual circumstances, such as, for example, those associated with an ongoing conflict, there are few if any reasons why a country cannot meet these tests to a high standard, provided that the political will to do so exists. (I should here observe in passing that any reasonable observer will be prepared to make allowances for shortcomings in an election process which flow from unavoidable environmental factors, such as poverty, bad weather, poor infrastructure or lack of transport resources. But too often, misbehaviour by autocratic politicians seems to be treated as just another environmental factor. Since one of the aims of democratisation is to eliminate such misbehaviour, to discount it when assessing elections is in my view downright perverse.)

All of that having been said, there are some challenges which can arise when assessing the freedom and fairness of elections. Perhaps the greatest is that of deciding what judgement should be made of a process which substantively satisfies some of the key requirements, but falls short on others. This is by no means an unusual situation, and the problem is that there are, in fact, no clear international standards for giving weight to the different criteria. This introduces an element of subjectivity when observers are expected or even pressured to make an overall binary judgement on whether or not an election has been 'free and fair'. This, however, is not so much an argument against the validity of the various elements of the tests for freedom and fairness, as an argument against overall binary judgements. Perhaps the most honest way of resolving this dilemma is for observers to provide assessments against the individual criteria, while leaving it to others to make their own overall judgements.

A second difficulty is that in some cases, an electoral process which has clearly been deficient when judged against the freedom and fairness criteria may nevertheless be validated by its own outcome. The 1999 'popular consultation' (referendum) to determine the future of East Timor provides a good example of this. The pre-voting period was so drastically tainted by intimidation directed against supporters of independence by militias sponsored by the Indonesian military that an objective observer assessing the process without knowing the outcome could hardly have reached any other conclusion than that the poll would not be free and fair. As it happened, however, the voters stood up with great courage to the pressure which had been placed on them, and voted for independence. In the circumstances, no reasonable observer could have doubted that the result of the ballot should be implemented. This case highlights the need for the exercise of intelligent judgement when assessing the quality of an election process: in such extreme situations, a mechanistic application of tests can give rise to a manifestly unreasonable conclusion.

Having discussed freedom and fairness, I now want to highlight the second main approach to the sourcing of standards for elections. It has been argued from time to time that the application of international standards in some sense impinges upon the sovereignty of the country whose elections are being observed. This has given rise to an alternative approach, most associated with the work of the Carter Center. They tend to pursue their analyses by exploring the legal commitments, domestic and international, which a country itself has voluntarily made; and testing the quality of the country's election against those commitments. In pursuit of that approach, the Carter Center has developed a very substantial database for the identification of such commitments.[9] The implication of this is that a slightly different set of tests may have to be applied in each country.

Typical observation activities

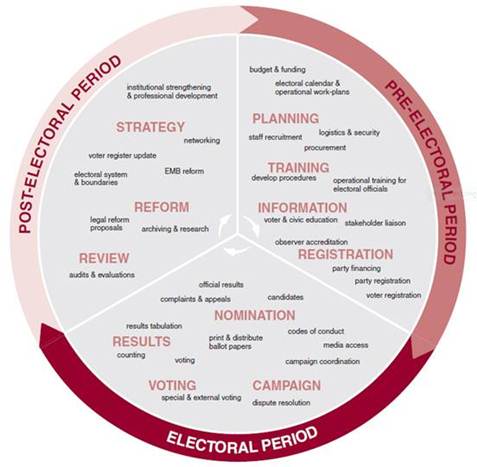

So far we have discussed what observation is, and the standards which are relevant to it. Let me now consider in a little more detail specific observation activities. The public often perceives observers stereotypically as people who arrive in a country a few days before polling day, visit as many polling stations as possible, deliver a judgement late on polling day or within a couple of days thereafter, and depart. Among the professionals, this is no longer the case. In the last 25 years, one of the biggest changes in defined best practice for election observation has been the greater emphasis placed on the duty to be comprehensive. It is now generally recognised that, as the late F. Clifton White put it, 'only an amateur steals an election on polling day'. More generally, it has come to be realised that an election takes place at the end of a cycle of preparatory activities, all of which potentially can impact on its success or failure and therefore need to be assessed. Bodies such as the European Union and the OSCE's Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) now insist on deploying long-term observers weeks if not months in advance of polling, and on analysing as many elements of the process as possible, including in particular the legal framework for the election, the nature of the political environment (including opportunities for media access), and both pre- and post-election dispute resolution.

Figure 1: The Electoral Cycle from International IDEA, Electoral Management Design: The International IDEA Handbook, International IDEA, Stockholm, 2006, p. 16 © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2006

The work of modern observers can often extend beyond the simple recording of information; compilation and analysis of data may also be required. This sometimes takes the form of a 'quick count', which involves observers from a random selection of polling stations transmitting count results to a central point for compilation, to enable an early indication of the nationwide electoral trend.[10] In Indonesia, quick counts conducted by civil society organisations working in conjunction with the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) have been spectacularly accurate at recent polls. Increasingly, observers are also finding it necessary to engage in 'election forensics', analysing results reported from polling stations in an attempt to identify implausible or suspicious-looking patterns in the data which may require further investigation.

International observation continues, however, to face one unavoidable challenge, which is the simple scale of election processes. Years ago I made a comment in a paper, which has since been very widely quoted, that an election is the largest and most complex logistical operation which a country ever faces in peacetime, since it involves putting the entire adult population of the country through a prescribed process, under tight timeframes, sometimes as short as one day. If you think about what would be involved in vaccinating every adult in a country against polio on one day, you get a sense of the scale of the activity. Furthermore, elections by definition are decentralised: the voting facilities have to be taken to the people, wherever they are. In the smallest countries, for example some of the Pacific island states, it may be possible for international observers to visit a fair proportion of the polling stations. But in a country like Indonesia, which has nearly half a million polling stations, coverage on such a scale is simply out of the question. This means that even observers who aspire to judge every functional aspect of the election process must inevitably draw their conclusions on the strength of very limited information.

Depending on the character of the country and of the observers, other obstacles are also likely to be found in their path. It will not always be the case that international observers will speak the language of the country; and they may or may not be well attuned to the sorts of subtle cultural signals which will tell them what is really going on in a place. As it happens, I do not speak Tetum, the lingua franca of East Timor, let alone any of the other languages which are spoken locally. In the observation I have done there, I have however always been lucky in having the indispensable assistance of Timorese friends who interpreted for me: which involved not just translating conversations, but also 'interpreting' in a broader sense the environment in which the election was taking place-whether for example, the voters felt confident or fearful.

Sometimes, observers are deployed who have neither a knowledge of the local language and culture nor a deep understanding of electoral processes. For them, the events they are witnessing may be particularly opaque.[11]

Faced with these sorts of challenges, it is tempting for observers to fall back on a relatively mechanistic approach to the work, which involves visiting as many polling places as possible, and completing at each one a detailed questionnaire documenting aspects of the process-did the poll open on time?; were the ballot boxes properly sealed?; was indelible ink correctly applied to the voter's fingers?-and so on. This is fine as far as it goes, but unless the polling places visited have been chosen at random, there is no particular basis for extrapolating statistical findings so as to reach conclusions about the overall process. (Many an observation team has proudly asserted that its members visited a 'random' or 'representative' sample of polling places, but in most cases that simply is not true: especially when teams include VIPs, they tend to go to places that are secure, accessible and comfortable.)

Notwithstanding these challenges, there is great pressure on observers to reach an overall conclusion; and in this sense, election observation is still far short of being a science. Natural scientists are driven to their conclusions purely by evidence, and feel no particular embarrassment in noting that on a specific point, the evidence is inconclusive. But rarely indeed will you find election observers who at the end of the process say 'we are unsure what we saw, and we cannot offer a conclusion'. That is not what is expected of them by any of the other players, and, perhaps more significantly, is not an approach which will ensure the free flow of funding for future observation operations.

Indeed, I am aware of only one case-though there have probably been a few others-of an observer who was prepared to come out after an election and say, in effect, 'I am genuinely unsure what I saw'. The person in question, Miss Ellen Bork, expressed this view in the Washington Post after spending time in Cambodia during the highly problematical elections of 1998.[12] Realistically, observers should be saying these sorts of things rather more often than they do.

A greater willingness to offer indeterminate conclusions would also open the way to a more sophisticated approach to the challenge observers invariably face of balancing in their analysis what they have seen during the observation process, and what they know (or should know) of the history of a country. Realistically and typically, an observer going into a country with a history of democracy and legitimate elections will start with a presumption that that is what he or she is going to see, and will require overwhelming evidence to the contrary before concluding that the election was not free and fair. On the other hand, an observer going into a country with a history of oppression, insecurity and electoral manipulation can rightly bring to his or her work a major element of scepticism, such that most compelling evidence will be needed for the election to be given a pass mark. Both of these perspectives are easier to implement in practice if observers are relieved of the obligation to make binary judgements, and are prepared in some cases to issue reports which express legitimate uncertainty.

There is one more point I would like to make here, and that relates to the priority which should or should not be given to eyewitness reports. I have taken part in observer briefings where it has been argued by some of those present that conclusions must be reached purely and exclusively on the basis of what observers see with their own eyes. To me, that seems likely to be very limiting in practice. The obligation on observers to be transparent and accurate does not intrinsically exclude reliance on compelling second-hand or circumstantial evidence. Judges, juries and police are not expected to act only on the basis of what they have seen with their own eyes. In any case, as was noted over 50 years ago by the late journalist and broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge, there have been any number of cases where the purported testimony of eyewitnesses turned out to be fundamentally unreliable.[13]

Context of observation

My description of election observation up to this point may well have given you the impression that it is a relatively straightforward exercise, albeit one requiring a good deal of attention to detail and careful judgement. Such a view is probably too sanguine: one of the great paradoxes of observation is that while it is supposed to be politically neutral, it takes place in a highly politicised context, which is what I now want to discuss.

At one level, it might be thought that the purpose of observation is an obvious one, rooted purely in the definitions, standards and activities we have already discussed. Observation, on that view, is an objective, almost clinical, process of finding facts, applying principles and reaching conclusions; similar in many ways to the work of a judge, jury, or auditor. The ultimate purpose of such work is to tell the truth, it being believed that in the long run this is the best way of enhancing the consolidation of democracy in a country. It is also often hoped that the work of observers will in itself have a direct positive impact on an electoral process. The following objectives will often be seen as important:

- to identify, well before the campaign, polling and counting phases of the process, shortcomings, for example in the legal framework, or in planning and preparation by the election management body, which are likely, if unaddressed, to undermine the quality and credibility of the election.

- to influence in a constructive way the persons and institutions responsible for developing the legal, regulatory and administrative framework for the electoral process.

- to support, through the conduct of professional analysis, the work of citizens and organisations in the country who are actively seeking to enhance the quality of electoral processes.

- to deter fraud, maladministration and misbehaviour by making it clear that it is unlikely to go unreported.

- to facilitate rapid reaction to emerging problems, for example intimidation, violence, or conflict between supporters of parties or candidates, by putting in place a mechanism for objective and timely reporting on them and, thereby,

- to bolster public confidence, and to encourage those who have lost through a legitimate process to accept defeat gracefully.

In practice, however, different players are likely to have different hopes for, and expectations of, the observation process.

First, we can consider the country which has invited observers to be present. Its hope will undoubtedly be to bolster the perception of the legitimacy of its election process, and of the government which flows from it. If the country is genuinely trying to improve the quality of its democracy, it is likely to be open to constructive observations and criticisms which will help it to improve future elections; but it will not want to see its elections damned. It may also invite observers as part of a broader strategy of engagement with allies, neighbours, friendly countries and international organisations, especially if those players have been involved in providing prior support for the consolidation of the electoral and democratic processes in the country. Sometimes, invitations will have been issued under a degree of pressure or duress, for example if it is made clear to a mendicant country that permitting observers to be present will be a precondition for ongoing aid.

Secondly, we can consider countries or organisations which deploy observers. Again a number of different interests are likely to come into play. Where a country deploys an official observer mission to another country, that is usually done in the context of a much broader political relationship between the two countries, and sometimes with other countries in the region as well. The broadest purpose of the deployment is likely to be to enhance, in whatever way is thought desirable in the short term, the national interests of the deploying country. More specifically, a country may wish to become officially engaged in the observation of an electoral process in another country for some or all of the following reasons:

- to send a signal of political support for the other country's democratic process.

- to send a similar signal of political support to the voters of that country.

- to avoid giving offence, in circumstances where it might be impolitic for an invitation to observe to be refused.

- to signal an ongoing commitment to the country if other, perhaps more expensive, forms of support (such as a military presence on the ground) are being withdrawn or refused.

- to attempt to exercise beneficial short-term influence in cases where an electoral process in the other country appears likely to run into difficulties.

- to obtain the type of broader influence over the electoral process which can only be applied by those who are seen to be constructively engaged with it.

- to influence, post-election, the way in which the electoral process is generally perceived.

- to illuminate decisions on the retention of sanctions or the delivery of development assistance, in cases where the quality of the electoral process in question has implicitly or explicitly been identified as a determining factor to be taken into account.

- to respond to domestic interests/pressures (for example, from a community of expatriates originally from the country in which observation is contemplated).

All but the last of these objectives are also likely to be relevant to observation by intergovernmental organisations (which, furthermore, will face internal imperatives to take account of the perspectives of their constituent members).

Electoral observation may also be seen as an instrument for strengthening the democratic institutions and culture in a country. From this perspective, additional objectives may be:

- to highlight to the people of the country the importance of, respect for, and compliance with, democratic norms.

- to provide moral and practical support to the people and institutions in the country who are also pursuing that aim.

- to build links between people and organisations in different countries who or which are engaged with, and supportive of, electoral processes.

- to encourage the use of common measurement tools, especially in situations where the relationship between well-intentioned observer groups has been competitive rather than complementary.

- to support the development of a domestic capacity for analysis and observation (and perhaps, thereby, to help develop future cadres of international observers).

A good deal of election observation these days takes place under the auspices of respected international bodies which owe a substantial portion of their credibility as observers to the reputation they have built up for objectivity and honesty. Organisations which fall into this category include ODIHR; the European Union; and, from the United States, NDI. These bodies are active in a range of different countries, and have more to lose from adopting a biased or tendentious approach to observation than from 'letting the chips fall'.

Finally, some observation is done by relatively small ad hoc groups whose interest is not in the observation process per se, but in a relationship with a particular country. I took part in such an observation process last year, under the auspices of the various friendship groups which have sprung up across Australia linking localities here to towns and villages in East Timor. In that case, one of the primary purposes of the exercise was to strengthen people-to-people links.

Observers, whatever their hopes and expectations, are also to some extent at the mercy of the objective realities of the country in which they are deployed.

At one end of the scale, some countries are still running elections which are truly dire: corrupt, badly organised, and in no sense free and fair. More often than not, these do not pose such a problem for observers, because they will not be there. Where the defects have been centrally organised by the incumbent regime, it is unlikely to want to have independent witnesses on the ground. Occasionally, such defects are not centrally organised, but rather arise from a lack of security, the enduring influence of a basically non-democratic culture, or widespread retail rather than wholesale fraud. In such a situation, friendly countries may well be invited to send observers, but, sensing the way the wind is blowing, may decline to do so, knowing that their delegations on the ground could find themselves impossibly conflicted between telling the truth and causing offence to allies or friends. 'Them that ask no questions isn't told a lie'.[14]

At the other end of the scale, observers will sometimes find themselves looking at a good, peaceful election, which presents them with really no ethical or moral dilemmas. They will be able to make positive comments and suggestions, and their hosts will wish them well as they leave.

In the middle of the scale, one finds perhaps the most challenging context: elections which are not a pure charade, but are nevertheless obviously seriously defective in one way or another. These are the polls the perceptions of which are likely to shift one way or another, depending on what international observers have to say about them.

Taken as a whole, these contextual issues can significantly complicate the work of observers, and at times place them under considerable stress.

Challenges

I would like to conclude by discussing some of the challenges which I think international observation is facing or will soon face. I want to mention three which seem to me to be particularly significant: politicisation; increasing population mobility worldwide; and the ever-widening use of technology in elections.

Of these, politicisation is perhaps the most obvious challenge. Nations invite international observers to be present in the hope that their elections will be endorsed. For this to be helpful to democracy, however, observers need to maintain their standards, so that the conduct of legitimate elections is the only road to endorsement. Some autocrats, however, have realised that with a bit of luck and effort, they can have their cake and eat it too. For them, the ideal is to be able to manipulate an election to their own advantage, while still having it endorsed by the international community. This aim may be achieved in a number of ways. Manipulation may be made ever more subtle, perhaps taking the form of low-level but pervasive intimidation which can be difficult for outsiders to detect, but nevertheless most effective. If, for example, an incumbent regime makes it clear to its people, through the totality of its conduct over a long period of time, that if it loses an election there is likely to be chaos or bloodshed, this in effect is a form of collective intimidation directed at the entire population; but it may not need to be manifested in overt acts of violence while observers are around. At this point, some of the constraints faced by observers start to come into play. Those who make a fetish of eyewitness evidence will deny that factors such as that I have just described can legitimately be taken into account in assessing an election.

More particularly, however, these sorts of strategies on the parts of autocrats may be complemented by weakness on the part of observers. As I noted previously, observation is often undertaken in pursuit of political purposes other than those which are most obvious. If, for example, an official observer team has been deployed from one country to another with the aim of strengthening a bilateral relationship, its default position is likely to be a preference not to have to say anything terribly critical: it may well then seek to 'paint a bullseye around the spot where the arrow happened to land'. Observers who want to proceed in that way with a degree of sophistication have a number of options open to them. They may refuse to take account of events which they have not seen with their own eyes; they may give the benefit of the doubt to the incumbents; or they may seek to take advantage of ambiguities in the concept of free and fair elections to make sanguine rather than critical comments.

This syndrome can be particularly troubling in situations where observers see their role as being one of resolving conflict rather than supporting democratic processes. Reasoning from such a mindset, it is all too easy for observers to conclude that criticism of an election process is likely to lead to further conflict, and that therefore it is more responsible for them to pull their punches. This, however, basically creates an in-built bias in favour of incumbents, since they are the players who typically control the apparatus of state repression, and therefore have the greatest capacity to turn violence on and off. (I would observe in passing that this is one of the reasons why there are far more examples of elections being stolen by incumbent governments than by oppositions.)

Even where observers are determined to do their job properly, attempts may be made to pressure or manipulate them. A former colleague of mine who has done a lot of work internationally gave me the following example of this quite recently:

A good friend of mine was involved in another observation team ... some years ago and she would not agree to the wording of the report-the pressure put on her ended up with a call from the President's office telling her to sign-those guys really protect each other.

My personal view is that the single greatest threat to the integrity of election observation comes from attempts by observers to anticipate the possible political outcomes flowing from their observations, and to tailor their findings accordingly. When such an approach is taken, true neutrality is impossible to achieve. When briefing observers in the past, I have always told them that their role is akin to that of a jury, and that jury members have no right or responsibility to consider whether a particular conviction or acquittal is likely to give rise to trouble in the streets. The same sort of thing, of course, could be said of auditors: if they find that a corporation's books have been cooked, the fact that revealing this may cause the share price to tank is not their problem. In both cases, the standard neutral approach of letting the chips fall is motivated by a belief that in the long term having neutral juries and auditing is overwhelmingly more important for a society than any short-term costs which may flow from particular judgements. To put it bluntly, observers who cover up malpractice for political reasons are accessories after the fact, and are as culpable as the fraudsters.

The politicisation of international election observation leads to some sad conclusions[15]:

- First, a dishonest, tendentious or politicised observation process can be positively damaging, if it helps to confer undeserved legitimacy on an election or a government.

- Secondly, the people of the country concerned will typically know what has in fact been going on, and the sight of international observers involved in what they are likely to see as a cover-up may encourage them to lose faith in democracy, and in the international community as a guarantor thereof.

In addition, politicisation can fundamentally call into question the point of investing in international rather than domestic observation. There are, in fact, considerable benefits in developing a domestic election observation capacity in a country. It can help to build a sense of popular ownership of the democratic process. Domestic observation can provide a much more comprehensive coverage of an election than international observers can ever hope to achieve, and at much less cost. Domestic observers are also likely to have language skills and cultural sensitivity which will give them much greater insights into what is really happening at the grass roots. Against all these points, it has historically been argued that international observers bring to their task technical knowledge, experience and a disinterested neutrality. But if, in fact, international observers are also pursuing extraneous political interests, their comparative advantage largely falls away.

Let me turn now to what I see as the second major challenge which observers are increasingly facing: that of population mobility. It used to be the case that observers of elections of a particular country could simply focus their activities in that country. Now, however, the increasing ease of population movement is leading worldwide to greater pressures on election management bodies to provide out-of-country voting facilities. This is true both for rich countries, whose citizens can readily afford to travel, and for poorer countries, where they are enjoying increasing opportunities to go to richer countries where they can earn money which can be remitted home. Out-of-country voting typically uses different modalities to voting at home, including postal and pre-poll voting, and voting in embassies, as well as different counting mechanisms. If a significant proportion of a country's population are voting in other countries, the imperative for election observation to be comprehensive implies that observation operations will have to be much more widespread. This gives rise to implications beyond mere cost: just because country A has invited observers to go there to witness its election does not mean that country B, where country A's citizens are also voting, will be prepared to welcome observers too.

A final challenge arises from the increasing technological sophistication of elections.[16] In bygone days, voter registration tended to be done on cards or in books, and was readily observable. Now, particularly in Third World and post-conflict countries, registration tends to make use of computerised biometric technology, and assessing whether the underlying systems are accurately recording data requires a good deal more technical knowledge on the part of observers than was previously the case. This is even more pronounced when electronic voting is introduced: and a number of organisations have already started to examine the distinctive challenges associated with observing electronic elections, where there may be no ballot papers, and possibly significant distrust of the machines being used.[17]

Most problematical of all is the observation of internet voting. Throughout the world, election management bodies are coming under increasing pressure from voters, political parties and governments to implement, or at least consider implementing, some sort of internet voting. Additional impetus is given to this by the sense that internet voting may provide a cheap, convenient and effective way of enfranchising out-of-country voters.

There is a widespread, naive sense that because the internet is used in so many different contexts, including sensitive ones such as banking, it must be possible in principle to use it relatively easily for voting. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth: internet voting gives rise to a large number of difficult problems, most of which have not yet been solved, and some of which are arguably insoluble in principle. One of these is simply how to make all elements of internet voting transparent to observation by party agents and observers.[18]

For that reason I have a strong suspicion that sometime in the next 10 years we are going to see a meltdown at an election somewhere in the world where a failed attempt has been made to introduce internet voting. It is anyone's guess how any observers deployed to monitor that election will be able to cope.

Question- I wonder about turning the tables-what your views would be about Australia inviting international observers to come and take a look at our next election. Clive Palmer and others have made comments about the possibility of poor identification processes and also the possibility of multiple voting in Australia. So, with that put in the public arena, I wonder what your comment would be.

Michael Maley- Provided that you get professional observers, I cannot see any objection in principle to such a process. As I mentioned earlier, the different OSCE (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) countries have all made a commitment to have their peers coming as observers and, frankly, Australia has nothing to be ashamed of in its processes. I cannot see any objection in principle to it.

Question- Michael, you are with the Centre for Democratic Institutions (CDI). What is their focus at the moment in terms of international elections?

Michael Maley- They are not deeply involved in international elections. Their work has tended to be more on parliamentary strengthening and political party strengthening. But as of now there is a process being kicked off within the government-because CDI is a totally government-funded organisation-to think more about what is the best sort of Australian involvement in governance support around the world. That is going to take a bit of time. What comes out of that I think remains to be seen. But there are several well-known pillars of any sort of democratic, representative process. One is free, fair and legitimate elections; another one is an effective, empowered parliament; a third one is a community engagement with both parliamentary processes and electoral processes.

It is very easy to think of elections as being something that is delivered by an electoral commission to the community, but if you look around the world one of the things that you pick up is that the most successful elections in the most successful democracies are all basically community undertakings. Everybody has a legitimate role to play. We do not tend to think about this very much in Australia, because the contribution that the people make and the parties make is what they don't do. They don't misbehave. It never enters your mind to try to buy your next-door neighbour's vote. You don't threaten people as they are going to a polling place. But when you go to a country where these sorts of problems are endemic, you come to realise just how important is the contribution that everybody makes, not just the electoral commission. And a lot of thinking about how to strengthen governance and democracy in other countries is going beyond just the mechanics of the process to thinking about how you can reinforce this democratic culture. And cultures are not things that are made and unmade overnight. I used to say to people, 'You wouldn't think you could get the Mafia out of Sicily by running a civic education program'. There are a lot of interests that are there and it takes time, but it is worth the effort.

Question- Do we still need international observation in light of the three points that I am going to highlight: Firstly, if we need it, where can we place it on the electoral cycle if it is really a relevant point to the electoral cycle process? What I have observed is that there is somehow a spirit of silence or a dominant influence among the observers. That is, if the EU or another organisation-maybe a smaller one-is going to observe the same elections, if the dominant one starts making a statement that these elections were not free and fair, you find that everyone who is observing the elections-their results are still flowing around them. So there is like what I am going to call a standard deviation of the reports that are being issued by observers. Their reports or their recommendations tend to go around the very same things.

The second thing that I have observed is: are international observers really independent from their financiers? I will give you an example. If am working for the EU and the EU has been pressing for a regime change in that country and I go under the sponsorship of the EU, in my observation report will I really be independent from those who sponsored me? If my sponsors are saying the regime is bad and I go there and do a report, what are the chances that I will do a report and say, 'These elections were free and fair'? Will I not be influenced by those who sent me?

The third point is: do we still need the international observers when you can go and observe a thing happening and you regret that you cannot change it but you do not have the powers to do so? Should we not divert these resources to support the stakeholders who are really involved in the elections from preparation up to implementation, who might have the power or put the money to a better use which can directly influence the outcome of the election?

Michael Maley- I would make a few observations in response to the points that you have raised. Where you get involved in the cycle is possibly not as important as what you cover in the cycle. And in any given country you have a history of how elections have proceeded in the past which may inform your thinking about which areas of activity require the greatest concentration of effort as an observer to try to make some sort of evaluation of the process. So in some countries, for example, it is well known that there are problems with the voter register and there may be problems because of fraud; there may be problems because of the inherent difficulty in keeping a database up to date if you do not have a culture of updating your information and so on. And in those sorts of circumstances observers will take that into account and try to concentrate on, or make sure that they give due attention to, the issue of voter registration. In other areas, typically as you get towards the election process in things like nomination there are great opportunities there for manipulation of the process through rejection of legitimate nominations and all sorts of things. For some things, like the electoral law, you do not necessarily have to be in the country when the law is being made. You can read it as a desk exercise. You do not even have to be in the country to do that sort of analysis.

So it is going to vary a little bit from topic to topic as to what is the optimal way of approaching it. Typically what bodies like the European Union do these days when they deploy observers is they will have a multidisciplinary team-they will have a legal expert, they will have what they call an elections expert, they will have a security expert, usually a media expert and sometimes a gender expert-to try to make sure that a lot of these key functional activities are properly covered in their analysis and work.

On the question of independence: it is a very difficult one, and I am sceptical about whether a lot of bodies are as independent as they say they are. Having seen this from the inside, I do have a sense that there are a lot of different interests coming around, and any observer team has a lot of pressure on it one way or the other. I have been put under this sort of pressure myself-not intensely, but it was there. That is not to say that you cannot still do a professional job. What you really want to look at is the quality of the analysis. You can tell a good report from a bad report, and this is important when you have competing conclusions coming out from different observers. You really have to look at: how did they do their work? Were they there just for a few days, or did they really intensively analyse the situation? How much evidence have they presented in their reports? How well analysed is it? Is it just impressionistic, or did they cover a lot of places?

One of the arguments that is going on about this election in Azerbaijan is that the one team that was critical basically visited, I think, 58 per cent of polling booths. They covered the counting at a lot of places, and they saw it going to pieces in a lot of places with ballot-stuffing and fraud and that sort of thing. Some of the other groups, which said how good it was, did not actually watch any counting and really just said, 'We went around, and we liked what we saw'. You would have to say that you give priority in analysing those sorts of conclusions to the people who have actually presented some evidence and some argument.

Question- You may have covered some of what I wanted to ask about in what you have just said, but could I ask you to tell us a little about the composition of an Australian observer delegation and how it would work? Is it composed solely of electoral officials? You have mentioned security people. Would it include diplomatic officials either from the local embassy or from the Department of Foreign Affairs? If it does have this wider composition and there are different views on the effect on the bilateral relationship, how would those sorts of issues be worked through?

Michael Maley- It is going to vary from case to case. Sometimes there is a desire to make these parliamentary teams. Typically what you will have there is the MPs as the lead players, often supplemented by electoral officials-usually only one-and sometimes diplomats or retired diplomats who can contribute to the deliberations and who are experienced with the country. You sometimes have parliamentarians who have been to a country several times, so they bring back their own experiences as well.

If, on the other hand, it is purely an official delegation, you will not necessarily have MPs there. It may well be a situation where you do not really want to get involved very much in observation of the country but to say no would itself be a political signal you do not want to send. So you then have the option of getting people from the embassy in the capital accredited as observers, and they might do a very low-key operation where they do not say very much and report back to the government rather than issue a public report. So there are a lot of different options along the continuum.

Australia has not really been involved in developing its own systematic methodology for observation in the way that the European Union or the Carter Center have done. They have put a lot of effort into saying exactly how they are going to do their work, because it is their core business, whereas, in Australia, election observation is very much an adjunct to the broader political and bilateral relationship between Australia and the country concerned, and there tends frankly to be a bit of scrambling around when an invitation comes to observe-Should we accept? Should we decline? If not, how are going to do it?-and there is not a template that is conveniently there, ready to be used.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 6 December 2013.

[1] For an example of the sorts of detailed handbooks which the better organisations now use for the guidance of their observers, see Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Election Observation Handbook, 6th edn, 2010, http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/68434. The European Union has for several years had a structured training and accreditation program for its election observers.

[2] See, for example, Eric C. Bjornlund, Beyond Free and Fair: Monitoring Elections and Building Democracy, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 2004; Horacio Boneo, 'Observation of elections', in Richard Rose (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Elections, CQ Press, Washington D.C., 2000; Thomas Carothers, 'The observers observed', Journal of Democracy, vol. 8, no. 3, 1997, pp. 17-31; Judith Kelley, 'Assessing the complex evolution of norms: The rise of international election monitoring', International Organization, vol. 62, no. 2, 2008, pp. 221-55; Judith Kelley, 'The more the merrier?: The effects of having multiple international election monitoring organizations', Perspectives on Politics, vol. 7, no. 1, 2009, pp. 59-64; Judith Kelley, 'D-minus elections: The politics and norms of international election observation', International Organization, vol. 63, no. 4, 2009, pp. 765-87; Judith G. Kelley, Monitoring Democracy: When International Election Observation Works, and Why It Often Fails, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2012; Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Election Observation: A Decade of Monitoring Elections: The People and the Practice, 2005, http://www.osce.org/ odihr/elections/17165.

[3] National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation and Code of Conduct for International Election Observers, 2005, http://www.ndi.org/files/1923_declaration_102705_0.pdf, p. 2.

[4] There are, in fact, models for activities akin to observation, but distinct from it, which do contemplate intervention in the process in various ways: for example, the 'certification' undertaken by the UN of the 2007 elections in East Timor; the 'verification' by the UN of elections in the 1990s in Angola and Mozambique; and the 'supervision and control' by the UN of the 1989 elections in Namibia.

[5] See, for example, International IDEA, Code of Conduct for the Ethical and Professional Observation of Elections, International IDEA, Stockholm, 1997, http://aceproject.org/ main/samples/em/emx_o012.pdf; National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation and Code of Conduct for International Election Observers, op. cit.; and Global Network of Domestic Election Monitors, Declaration of Global Principles for Non-Partisan Election Observation and Monitoring by Citizen Organizations and Code of Conduct for Non-Partisan Citizen Election Observers and Monitors, 2012, http://www.gndem.org/sites/default/files/declaration/Declaration%20of%20Global%20 Principles%20%28as%20of%204.3.12%29.pdf.

[6] International IDEA, Code of Conduct for the Ethical and Professional Observation of Elections, op. cit., p. 11.

[7] Inter-Parliamentary Union, Declaration on Criteria for Free and Fair Elections, Geneva, 1994, http://www.ipu.org/cnl-e/154-free.htm.

[8] See, for example Guy S. Goodwin-Gill, Free and Fair Elections: International Law and Practice, Inter-Parliamentary Union, Geneva, 2006, www.ipu.org/pdf/publications/free&fair06-e.pdf; Jørgen Elklit, 'Free and fair elections', in Richard Rose (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Elections, CQ Press, Washington D.C., 2000; and Jørgen Elklit and Palle Svensson, 'What makes elections free and fair?', Journal of Democracy, vol. 8, no. 3, 1997, pp. 32-46.

[9] The Carter Center, Database of Obligations for Democratic Elections, 2013, http://www.cartercenter.org/des-search/des/Introduction.aspx. See also European Commission, Compendium of International Standards for Elections, 2nd edn, 2007, http://eeas.europa.eu/human_rights/election_observation/docs/compendium_en.pdf.

[10] See, Melissa Estok, Neil Nevitte and Glenn Cowan, The Quick Count and Election Observation: An NDI Guide for Civic Organizations and Political Parties, National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 2002, http://www.accessdemocracy.org/files/1417_elect_quickcounthdbk_1-30.pdf.

[11] Such observers can be positively dangerous if they go beyond the gathering of information and seek to provide advice to a country concerning future electoral policy. For better or for worse, the documented recommendations of international observers often carry considerable weight; but opinions on complex issues (such as, for example, how a country should manage its voter register) are really not worth much if based only on insights gained during a short visit at election time.

[12] See Ellen Bork, ' "Miracle on the Mekong" or orchestrated outcome?', Washington Post, 5 August 1998.

[13] Malcolm Muggeridge, 'The eye-witness fallacy', Encounter, vol. XVI, no. 5, 1961, pp. 86-9.

[14] The fact that the decision whether or not to deploy observers may be a difficult one was one of the reasons why International IDEA decided to promulgate guidelines on the subject. See International IDEA, Election Guidelines for Determining Involvement in International Election Observation, 2000, http://aceproject.org/ero-en/topics/election-integrity/Guidelines%20for%20determining%20 Observation.pdf.

[15] For a discussion of the very public (and, on the face of it, bitter) dispute over politicisation which broke out between different organs of the OSCE in the aftermath of the Azerbaijan election of October 2013, see European Stability Initiative, Disgraced: Azerbaijan and the End of Election Monitoring as We Know It, 2013, http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_document_id_145.pdf.

[16] For a discussion of a recent case in which expensive technology failed to live up to expectations, see Joel D. Barkan, 'Technology is not democracy', Journal of Democracy, vol. 24, no. 3, 2013, pp. 156-65.

[17] See, for example, Jordi Barrat, Observing E-enabled Elections: How to Implement Regional Electoral Standards, International IDEA, Stockholm, 2012, http://www.idea.int/democracydialog/ upload/Observing-e-enabled-elections-how-to-implement-regional-electoral-standards.pdf.; Vladimir Pran and Patrick Merloe, Monitoring Electronic Technologies in Electoral Processes: An NDI Guide for Political Parties and Civic Organizations, National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, 2007, http://www.ndi.org/files/2267_elections_manuals_monitoringtech_0 .pdf; and The Carter Center, The Carter Center Handbook on Observing Electronic Voting, 2nd edn, 2012, http://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/peace/democracy/des/Carter-Center-E_voting-Handbook.pdf.

[18] For a detailed discussion of many of these issues, see Electoral Council of Australia and New Zealand, Internet Voting in Australian Election Systems, 2013, http://www.eca.gov.au/research/ files/internet-voting-australian-election-systems.pdf.

Prev | Contents | Next