Glenn Ryall

In September 2017 the High Court rejected two challenges to the legality of the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey in Wilkie v Commonwealth. From the Parliament's perspective this case was significant as it canvassed important issues relating to the Parliament's role in appropriating money, particularly for urgent expenditure. This paper will briefly outline Parliament's role in making appropriations and then consider the significance of the case to the extent that it emphasised that it is largely the role of the Parliament (and not the courts) to exercise control over appropriations. The paper concludes with a discussion of some options to increase parliamentary oversight of the appropriation mechanism known as the Advance to the Finance Minister (the Advance).

Background

The proceedings challenged the lawfulness of measures taken by the Commonwealth Government 'to direct and to fund the conduct of a [voluntary] survey of the views of Australian electors on the question of whether the law should be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry'.1 These measures followed the defeat in the Senate2 of a government bill—the Plebiscite (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill 2016—which would have authorised the holding of a compulsory plebiscite and appropriated the funds to pay for it.3

The plaintiffs' arguments

While the challenges also raised issues such as standing and the scope of the functions of the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), of particular relevance to the Parliament was the plaintiffs' challenge to the mechanism used to fund the survey—a determination made under section 10 of Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2017–2018. This determination (known as an Advance to the Finance Minister determination) provided funding of $122 million to the ABS to enable it to conduct the survey.4

The plaintiffs sought to challenge the validity of both section 10 itself and the Advance determination made under it.

The Advance to the Finance Minister

Section 10 of Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2017–2018 is a standard Advance to the Finance Minister provision. An Advance provision is included in each annual Appropriation Act to enable the Finance Minister to allocate additional funds to entities for expenditure in the relevant year. Provisions of this nature have been included in appropriation bills since 1901.5 The text of these provisions has remained unchanged since the enactment of Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2008–2009, as has the total amount that can be allocated under them ($675 million).6

A significant element of the case related to the interpretation of subsection 10(1) which makes it a precondition to the application of the remainder of section 10 that:

the Finance Minister is satisfied that there is an urgent need for expenditure, in the current year, that is not provided for, or is insufficiently provided for, in Schedule 1…because the expenditure was unforeseen until after the last day on which it was practicable to provide for it in the Bill for this Act before that Bill was introduced into the House of Representatives.7

If this precondition is met then the Finance Minister may make a determination to allocate additional funds to an entity listed in Schedule 1. The effect of such a determination is that the budget figures for an entity are increased so that an additional amount is included in the appropriation for the relevant entity. Importantly, subsection 10(4) exempts Advance determinations from parliamentary disallowance.

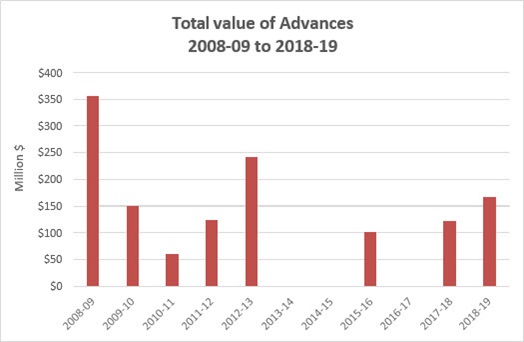

Breadth of use of the Advance

While the Advance to the Finance Minister is a relatively obscure mechanism, its significance is emphasised by the breadth of its use. As outlined below, since 2008–09 the Advance has been used 37 times to allocate over $1.3 billion in additional funds.

| Year |

No. of Advances |

Total value of Advances |

| 2008–09 |

9 |

$356,354,739 |

| 2009–10 |

6 |

$150,240,462 |

| 2010–11 |

5 |

$60,590,000 |

| 2011–12 |

7 |

$124,822,580 |

| 2012–13 |

5 |

$241,466,895 |

| 2013–14 |

- |

- |

| 2014–15 |

- |

- |

| 2015–16 |

1 |

$101,237,000 |

| 2016–17 |

- |

- |

| 2017–18 |

1 |

$122,000,000 |

| 2018–19 |

3 |

$167,939,000 |

| Total |

37 |

$1,324,650,676 |

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills (the Scrutiny of Bills Committee) has regularly commented on the Advance provisions, noting that they represent a significant delegation of legislative power to the executive.8 To demonstrate the breadth of circumstances in which the Advance provisions have been used, in 2017 the committee published details of a selection of Advances issued since 2006–07:9

| Year |

Purpose |

FRL No. |

Amount |

| 2006–07 |

To meet commitments in relation to payments to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to provide

Australian television in the Asia Pacific region |

F2006L02669 |

$8,989,493 |

| 2007–08 |

To cover funding obligations for the Mersey Community Hospital, Tasmanian Health Initiatives, Year of the Blood Donor measure and ongoing blood

and organ donation services |

F2007L04155 |

$48,760,078 |

| 2008–09 |

To enable payments to local governments through the

Regional and Local Community Infrastructure Program |

F2009L00712 |

$206,500,247 |

| 2009–10 |

To enable the payment of an additional contribution to the International Monetary Fund Poverty Reduction

and Growth Trust |

F2010L00149 |

$29,675,000 |

| 2010–11 |

To cover payments for the 2011–12 budget measure

'Supporting football in the lead up to the 2015 Asian Cup' |

F2011L01128 |

$7,500,000 |

| 2011–12 |

To enable the Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport to meet a shortfall of funding for expenditure relating to grants to arts and

culture bodies |

F2012L01523 |

$6,000,000 |

| 2012–13 |

To enable the Department of Health and Ageing to make payments through the Local Hospital Networks

Special Account to Victorian Local Hospital Networks |

F2013L00558 |

$107,000,000 |

| 2015–16 |

To enable the AEC to implement the electoral reforms in the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 2016, as well as to bring forward election preparations for the

2016 Federal Election |

F2016L00673 |

$101,237,000 |

| 2017–18 |

To facilitate a voluntary postal plebiscite for all

Australians enrolled on the Commonwealth electoral roll, conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics |

F2017L01005 |

$122,000,000 |

Most recently, the committee noted that in 2018–19 the Advance provisions were used to allocate funding for:

- an expansion of the Drought Communities Program ($75,379,000)10

- the re-opening of the Christmas Island Detention Centre following the passage of the Home Affairs Legislation Amendment (Miscellaneous Measures) Act 2019 ($52,560,000)11

- a payment to South Australian Government to assist councils in South Australia to upgrade and maintain their local road network ($40,000,000).12

Comprehensive details about the use of the Advance provisions since 2000–01 are available on the Department of Finance website.13

Parliament's role in making appropriations

Before examining the significance of Wilkie for the parliamentary control of appropriations it is useful to briefly consider what is meant by an appropriation generally and to outline Parliament's role in making them.

What is an appropriation?

At common law

In the English constitutional tradition, an appropriation is an Act by which Parliament authorises the expenditure of moneys of the Crown.14 This need for an appropriation to authorise expenditure of public moneys by the executive reflects a well-established common law rule that moneys of the Crown cannot be expended except under authority of an Act of Parliament. The rule 'arose out of the English Parliament's insistence that it rather than the sovereign should decide how revenue raised by taxation should be spent'15 and was clearly set out by Viscount Haldane in Auckland Harbour Board v The King:

it has been a principle of the British Constitution now for more than two centuries…that no money can be taken out of the consolidated Fund into which the revenues of the State have been paid, excepting under a distinct authorization from Parliament itself. The days are long gone by in which the Crown, or its servants, apart from Parliament, could give such an authorization…Any payment out of the consolidated fund made without Parliamentary authority is simply illegal and ultra vires…16

In Australia

In the context of Australia's written constitution a clear distinction is drawn between an appropriation and the substantive power to spend public moneys.17 Section 81 of the Constitution provides that:

all revenues or moneys raised or received by the Executive Government of the Commonwealth shall form one Consolidated Revenue Fund, to be appropriated for the purposes of the Commonwealth in the manner and subject to the charges and liabilities imposed by this Constitution.

Section 83 stipulates that 'no money shall be drawn from the Treasury of the Commonwealth except under an appropriation made by law'.

These provisions mean that an appropriation of money in the Australian context is 'simply the earmarking or segregating of it from the Consolidated Revenue Fund'18— it does not provide the executive with a substantive power to spend the appropriated moneys. This is because the 'substantive power to spend the public moneys of the Commonwealth is not to be found in s 81 or s 83, but elsewhere in the Constitution or statutes made under it'.19

The role of Parliament generally

Despite the limited function of the appropriation process itself as an earmarking exercise, it is nonetheless very important as it ensures that the Parliament maintains oversight over the expenditure of public moneys.20 Of particular importance in this regard is the language of sections 56 and 81 of the Constitution which mean that an appropriation can only be for a purpose which Parliament has determined.21

Together with the prohibition in section 83 of the Constitution, the requirement for an appropriation to be for a legislatively determined purpose results in an appropriation serving a dual function—'not only does it authorize the Crown to withdraw moneys from the Treasury, it restricts the expenditure to the particular purpose'.22

In Pape v Federal Commissioner of Taxation, Heydon J emphasised importance of the appropriation process:

The appropriation regulates the relationship between the legislature and the Executive. It vindicates the legislature's long-established right, in Westminster systems, to prevent the Executive spending money without legislative sanction…It also operates so as to restrict any expenditure of the money appropriated to the particular purpose for which it was appropriated. That is, it creates a duty – a duty not to spend outside the purpose in question.23

This constitutional limitation that an appropriation must be for a legislatively determined purpose means that there cannot be 'appropriations in blank, appropriations for no designated purpose, merely authorizing expenditure with no reference to purpose',24 nor can there be an 'appropriation in gross, authorizing the withdrawal of whatever sum the Executive Government may decide in the exercise of unfettered discretion'.25 As stated by Latham CJ, 'an Act which merely provided that a minister or some other person could spend a sum of money, no purpose of the expenditure being stated, would not be a valid appropriation Act'.26

The role of the Senate

In Wilkie the Court highlighted the constitutional role of both houses of the Parliament in the appropriation process, noting that an appropriation must be by law and therefore passed by both houses:

Sections 81 and 83 together give expression to the foundational principle of representative and responsible government “that no money can be taken out of the consolidated Fund into which the revenues of the State have been paid, excepting under a distinct authorization from Parliament itself”. The sections also prescribe the form of the requisite parliamentary authorisation: it must be by “law”. They thereby combine to exclude from the scheme of the Constitution “the once popular doctrine that money might become legally available for the service of Government upon the mere votes of supply by the Lower House”.27

As noted in Odgers' Australian Senate Practice, while section 53 of the Constitution means that appropriation bills may not originate in the Senate, this does not mean that the Senate is not an equal partner with the House of Representatives in making appropriations. In fact, the first Senate insisted that words be removed from the preamble of the Supply Bills 1901 which implied that the granting of appropriations was the work of the House of Representatives.28 Similarly, the Senate caused to be removed from the Governor-General's opening speech words implying that in the granting of appropriations the House of Representatives had some priority. The Senate has also exercised its right to decline to pass appropriation bills and items in such bills until relevant information is provided.29

The Court's decision

As noted above, the plaintiffs' challenge to the mechanism used to fund the postal survey was two pronged in that they sought to question the validity of section 10 itself, as well as the Advance determination made under it.

The validity of section 10

An impermissible delegation of legislative responsibility?

In relation to the validity of section 10, the plaintiffs suggested that Parliament had 'abdicated its legislative responsibility and impermissibly delegated its power of appropriation to the Finance Minister'.30 In this regard, the plaintiffs argued that section 10 conferred power on the Finance Minister to alter the Appropriation Act 'so as to supplement “by executive fiat” the amount appropriated by Parliament in Sch 1'.31

The Court rejected this argument and in its reasons considered the history of similar provisions dating back to 1901.32 The Court considered that the plaintiff's argument was based on a 'fundamental misconstruction', noting that 'the provision of Appropriation Act No 1 2017–2018 which appropriates the Consolidated Revenue Fund is s 12', and that 'appropriations are not made or brought into existence just before they are paid, but when the Act commences'.33 The Court held that:

Section 12 operated on and from the commencement of Appropriation Act No 1 2017–2018 as an immediate appropriation of money from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the totality of the purposes of the Act. Section 12 so operated as an immediate appropriation of the amount of

$295 million specified in s 10(3) in the same way as it operated as an immediate appropriation of the amount of $88,751,598,000 noted in s 6 to be the total of the items specified in Sch 1.34

Therefore the Court considered that the 'power of the Finance Minister to make [an Advance determination]…is not a power to supplement the total amount that has otherwise been appropriated by Parliament. The power is rather a power to allocate the whole or some part of the amount…that is already appropriated by s 12'.35

For a legislatively determined purpose?

In addition, the plaintiffs argued that section 10 was constitutionally invalid because, in enacting the provision, Parliament had transgressed the constitutional limitation that an appropriation must always be for a purpose identified by the Parliament. In rejecting this aspect of the plaintiffs' arguments the Court stated that the power of the Finance Minister to make an Advance determination is not 'at large if the precondition to the exercise of that power set out in s 10(1) is met'.36 In addition, the Court noted that the structure of the Advance provision means that the Finance Minister is limited to allocating 'the whole or some part of the amount of $295 million >to a specified “item” in respect of a specified “entity”'.37 It therefore could not be said that the Advance represented an 'appropriation in blank' or that it was an appropriation for no designated purpose.

Degree of specificity of the purpose of an appropriation is for Parliament to determine

The Court acknowledged that 'passing scepticism has from time to time been expressed academically, in the Senate and in this Court' as to how the Advance in the form in which it existed prior to 1999 'could be reconciled with the constitutional requirement for an appropriation to be for a legislatively determined purpose'.38 The Court concluded that the 'reconciliation lies in recalling that the degree of specificity of the purpose of an appropriation is for Parliament to determine' [emphasis added].39

The validity of the Advance determination

As noted above, the Advance determination itself was challenged on the basis that the Finance Minister had not met the precondition set out in section 10 to the exercise of his power to make the determination.40

Advance determinations difficult to challenge

Challenging the determination was difficult because the precondition rested upon the minister being 'satisfied' of an urgent need for unforeseen expenditure and reliance on the subjective 'satisfaction' of a decision-maker makes it difficult to challenge the exercise of the power under most grounds of judicial review.41 The Administrative Review Council has noted that the primary purpose of such provisions is to ensure that critical facts going to jurisdiction are to be determined by the administrative decision-maker (in this case the Finance Minister) rather than a court.42 However, these provisions do not preclude judicial review altogether. For example, in the case of the Advance, the Finance Minister's satisfaction must be formed reasonably and on a correct understanding of the law.43 In addition, the Finance Minister must not take into account a consideration which a court can determine in retrospect 'to be definitely extraneous to any objects the legislature could have had in view'.44 However, the Finance Minister is not obliged to act apolitically or quasi-judicially.45

'Urgent need' for the expenditure

In determining what satisfaction the Finance Minister is required to form, in order to meet the precondition in subsection 10(1) that there be an 'urgent need' for the expenditure, the Court separated the words 'urgent' and 'need'.46 The Court held that the 'notion of need does not require the expenditure to be critical or imperative'.47 Instead, it must be 'expenditure which ought to occur, whether for legal or practical or other reasons'.48 The Court rejected an argument that the need must arise from a source external to government.49

In relation to the term 'urgent' Twomey suggests that the term was 'stripped of substantive meaning'.50 The Court stated that urgency 'is a relative concept' and that, in the case of the Advance, urgency must be read 'in the context of the ordinary sequence of annual Appropriation Acts'.51 The Court therefore held that the 'question for the Finance Minister to weigh is why the expenditure that is needed in the current fiscal year…cannot await inclusion in Appropriation Act No 3' (i.e. the next scheduled Appropriation Act).52 Thus it appears that something will be 'urgent' 'simply because the government decides it should be dealt with before the next scheduled Appropriation Act'.53 In addition, while government guidelines in relation to the use of the Advance suggest that 'urgent need' should be interpreted quite strictly (e.g. a 'pressing or compelling' need to make a payment of money), the Court held that these do not amount to a legal constraint on the minister's powers.54

In addition to the Finance Minister being satisfied that there is an 'urgent need' for the expenditure, the minister must also be satisfied that the expenditure was 'unforeseen'. In this regard, the Court held that the question to be asked is: was the expenditure for the actual payments that are to be made unforeseen by the executive government? It emphasised that 'the question is not whether some other expenditure directed to achieving the same or a similar result might have been foreseen'.55 As a result, the Court concluded that the expenditure on the postal survey 'was unforeseen, even though the government had always intended to spend the relevant amount (or more) for the same purpose of being informed of the views of electors on same-sex marriage'.56

No need for government to consider introducing a special appropriation bill

In Wilkie the Court also emphasised that there is no need for the government to consider 'whether it is reasonable or practicable for the Government to introduce a Bill for a special appropriation' before using the Advance.57 The Court stated that nothing in the text of the Advance provision or the history of its use supports such a requirement. As a result, where needed expenditure does not exceed the amount of the Advance (e.g. $295 million in Appropriation Bill (No. 1)), 'that amount is already immediately available to meet the expenditure provided only that the precondition in s 10(1) is met'.58 In relation to the Court's reliance upon the history of the use of the Advance in this way, Twomey has suggested that it is hard to see how 'past abuse of the requirement for urgent necessity should justify present abuse of the requirement. Past practice cannot undo illegality or correct jurisdictional error'.59

Other matters relating to parliamentary control of appropriations

As well as specifically addressing issues relating to parliamentary oversight of the Advance, the Court reaffirmed that most aspects of the parliamentary appropriation process are not reviewable by the Court. The Court also alluded to the wide scope available to the executive to allocate appropriations against the very broadly framed 'outcomes' contained in modern appropriation bills.

Financial provisions of the Constitution not justiciable

Sections 53, 54 and 56 generally

Wilkie included commentary relating to the purposes of sections 53, 54 and 56 of the Constitution which, in part, regulate the process of enacting appropriation bills.60 Most significantly, the Court restated that these sections are procedural provisions that govern the internal activities of the Parliament and the relationship between the Senate and the House of Representatives, so the Court will not entertain challenges to laws where it is argued that those sections have not been followed.61 The interpretation and application of those sections of the Constitution are for both houses of the Parliament to determine between them.

Ordinary annual services of the government

The fact that the financial provisions of the Constitution in sections 53, 54 and 56 are non-justiciable was also affirmed by the Court's consideration of an argument advanced by the plaintiffs that section 10 of the Appropriation Act was in some way limited by the description in the long title of the Act, which states that it is an Act to appropriate money from the Consolidated Revenue Fund for the ordinary annual services of the government [emphasis added].62 The Court noted that the language 'ordinary annual services of the government' is drawn from sections 53 and 54 and therefore this 'statutory language has no justiciable content'.63

However, drawing on Brown v West,64 the Court did note that where there is settled, consistent and clear practice between the Senate and the House of Representatives in relation to what may be appropriately considered an appropriation for the 'ordinary annual services of the government' that practice may be relevant to the construction of the Advance provisions. The Court, however, noted that there is now considerable uncertainty in relation to parliamentary practice in this regard and, therefore in this case, there was 'an insufficient foundation for drawing a statutory implication which would confine the operation of [the Advance provision] to expenditure which a court might characterise as expenditure other than on new policies'.65

Broadly stated outcomes in appropriation bills

In outlining the background to the Advance determination, the Court also alluded to the wide scope available to the executive to allocate appropriations against the very broadly framed 'outcomes' contained in modern appropriation bills. In this regard the Court noted that the increased appropriation to the ABS provided for in the Advance determination could be used for expenditure on activities directed to the following 'broadly stated outcome' for the ABS:

Decisions on important matters made by governments, business and the broader community are informed by objective, relevant and trusted official statistics produced through the collection and integration of data, its analysis, and the provision of statistical information.66

The Court noted that the plaintiffs had not sought to argue 'that the activities to be carried out by the ABS [in running the postal survey] were incapable of answering the description of activities directed to this broadly stated outcome'.67 The fact that no argument was advanced in this regard emphasises the wide scope available to the executive to allocate appropriations against these very broadly framed 'outcomes' without any oversight from the Parliament or the courts.

Implications of the decision for parliamentary control of appropriations

Noting the Court's approach to the construction of the Advance provision outlined above, it is clear that Wilkie has emphasised that it is largely the role of the Parliament (and not the courts) to exercise control over appropriations, particularly use of the Advance to the Finance Minister.68 Twomey concluded that the High Court's decision in Wilkie means that the requirement for 'urgent need' is satisfied simply 'if the government decides that it wants to spend money in the period between appropriation bills'. In other words, there 'would appear to be no circumstances in which a government desire to spend could not satisfy the criteria of “urgent need” as interpreted by the High Court'.69 Twomey suggests that this means the Court's interpretation of the legislative restrictions on the exercise of the Advance renders them of no substantive effect and that:

This cannot be consistent with the intent of the provision. If Parliament had wanted to give the Minister power to authorise expenditure of the Advance on anything that the Government wanted, it would not have imposed the conditions in s 10. The fact that the Parliament did include this express limitation on the use of the Advance must indicate that it is intended to be a substantive limit on executive power.70

As a result, Twomey suggests that Wilkie has significant 'ramifications as a precedent which upholds the capacity of the Executive to allocate the appropriation of funds and to expend them, when there is existing standing authorisation in legislation to do so, without any parliamentary scrutiny and even against the will of Parliament', and that this 'undermines the foundational constitutional principle of responsible government'.71 More directly, it has been argued that 'the Court effectively waived the constitutional significance of the repeated defeat of the [Plebiscite (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill 2016] in the Senate'.72

If it is Parliament's intention that there should be enforceable preconditions to the expenditure of money by the executive under the Advance provision, Wilkie means that it is necessary for the Parliament to change the standard text of the Advance provision that is agreed to each year. However, there are also other options for increasing parliamentary oversight of the Advance.

Options for increased parliamentary oversight of the Advance to the Finance Minister

The text of the Advance provisions has remained the same for many years.73 The discussion above makes it clear that if the Parliament considered that the Advance provisions, as currently drafted, provide too much leeway to the executive government to expend money without sufficient parliamentary oversight, it is up to the Parliament to take action in this regard. Some potential options for increased parliamentary oversight include:

- more effectively utilising existing accountability mechanisms

- changing the preconditions that apply to the exercise of the Advance provisions

- changing the text of the Advance provisions to increase parliamentary oversight.

Utilising existing accountability mechanisms

Following recommendations made by former Senator Andrew Murray in his 2008 Review of Operation Sunlight: Overhauling Budgetary Transparency, a comprehensive annual report on the use of the Advance has been tabled in the Parliament.74 The report is subject to review by the Australian National Audit Office and is referred to legislation committees considering estimates.75 On occasion, senators have asked questions about the use of the Advance during estimates hearings and it is, of course, open to senators to continue to use this forum to scrutinise Advances in the future.76

The annual report on the use of the Advance is also considered in the Senate on a motion that the statements of expenditure be approved.77 Odgers' Australian Senate Practice explains that rejection of the motion would signify dissatisfaction with the statement as an accountability document.78 The Senate has never rejected such a motion—however it remains open to senators to utilise this existing mechanism to comment on the use of the Advance or to express the Senate's dissatisfaction.79 As this process only occurs some time after the Advance has already been utilised, it provides a mechanism for ensuring accountability and transparency after the fact but does not have a direct effect on the use of the Advance.

Changing the preconditions that apply to the exercise of the advance provisions

If it is considered that the existing (after-the-fact) accountability mechanisms described above are no longer sufficient in light of the Wilkie decision it may be desirable to change the preconditions that apply to the exercise of the Advance provisions. In this regard, an inquiry by a parliamentary committee may be an appropriate mechanism to assess whether changes are required and, if so, what amendments to the text of the Advance provisions would be required to give the preconditions more substantive effect. The Advance has been considered by a number of parliamentary committees in the past,80 and given the significance of the Wilkie decision it may now be appropriate for the Parliament to consider undertaking a further review.

Changing the Advance provisions to increase parliamentary oversight

Instead of changing the preconditions that apply to the exercise of the Advance provisions, a further option that could be considered (including by a parliamentary committee) would be the appropriateness of modifying the provisions to increase parliamentary oversight. Increasing parliamentary oversight could be achieved in a number of ways, including by:

- removing the current provision which makes Advance determinations exempt from the usual parliamentary disallowance process

- providing that Advance determinations are subject to a modified parliamentary disallowance process

- providing that Advance determinations do not come into effect until they have been approved by resolution of each house of the Parliament.

Removing the exemption from the usual parliamentary disallowance process

In relation to the first option of removing the current exemption from the usual parliamentary disallowance process, explanatory memoranda accompanying appropriation bills suggest that the Advance determinations should be exempt from disallowance on the basis that allowing the determinations to be disallowable 'would frustrate the purpose of the provision, which is to provide additional appropriation for urgent expenditure'.81

In relation to this explanation, it may be noted that subjecting Advance determinations to the usual disallowance process would not prevent the allocation of urgent additional funds. The additional moneys would become available to fund the urgent and unforeseen expenditure the day after the instrument was registered on the Federal Register of Legislation.82 The only circumstance in which allowing the Advance provisions to be subject to disallowance may cause difficulties would be in a situation where the executive was concerned that the determination may be disallowed by a house of the Parliament. While, at first glance, the uncertainty created during the disallowance period may be seen as problematic, in reality this would simply mean that the executive would more closely consider whether its use of the Advance provisions was genuinely for urgent and unforeseen expenditure. Such an approach would simply be a reassertion of the centuries-old rule that it is for the Parliament (and not the executive) to authorise expenditure of public moneys.

However, if the view is taken that even a small level of uncertainty is unacceptable,83 a modified parliamentary disallowance process and/or affirmative resolution process for Advance determinations may be considered appropriate.

Making advance determinations subject to a modified parliamentary disallowance process

As Odgers' Australian Senate Practice notes there are some forms of delegated legislation with different approval or disallowance procedures:

Some instruments require affirmative resolutions of both Houses to bring them into effect, while others do not take effect until the period for disallowance has passed. Some involve a combination of both methods. The Senate has amended bills to insert such provisions where it was thought that particular instruments merited special control procedures.84

Providing that Advance determinations be subject to a modified parliamentary disallowance process would ensure effective parliamentary oversight of the determinations while at the same time removing any period of uncertainty. For example, within the Finance portfolio, section 79 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 provides that certain determinations relating to special accounts do not commence until after a five sitting day disallowance period has passed.85 The explanatory memorandum to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Bill 2013 noted that the modified disallowance process in section 79 allows Parliament to consider whether a special account should be established before the determination takes effect and that the process 'seeks to strike a balance between the opportunity for parliamentary scrutiny of the government's intentions and the need to not unduly delay the functional operations of financial administration'.86 Such considerations may also be regarded as relevant to Advance determinations.

Making advance determinations subject to an affirmative resolution process

A further option to ensure effective parliamentary oversight while removing any period of uncertainty would be to make Advance determinations subject to an affirmative resolution process. An example of this process is set out in section 10B of the Health Insurance Act 1973, which provides that certain determinations do not come into effect until they are approved by resolution of each house of the Parliament.87 If such a process were implemented for Advance determinations it would be possible for a determination to swiftly come into effect with the positive approval of the Parliament. For example, each house of the Parliament could approve the determination on the first sitting day after the determination is made.88

Conclusion

The High Court's decision in Wilkie has emphasised that it is largely the role of the Parliament (and not the courts) to exercise control over appropriations, particularly use of the Advance to the Finance Minister. Put simply, so long as the text of the Advance provisions remains the same, the courts will not get involved in determining in any meaningful way whether expenditure under the provisions was objectively urgent—this determination is in the hands of the Finance Minister. If the Parliament considers that the Advance provisions, as currently drafted, provide too much leeway to the executive government to expend money without sufficient parliamentary oversight it is up to the Parliament to take action in this regard. Wilkie has made it clear that the High Court will not get involved.

APPENDIX

Advance to the Finance Minister Provisions for 2019–2020

Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2019–2020

10 Advance to the Finance Minister

- This section applies if the Finance Minister is satisfied that there is an urgent need for expenditure, in the current year, that is not provided for, or is insufficiently provided for, in Schedule 1:

- because of an erroneous omission or understatement; or

- because the expenditure was unforseen until after the last day on which it was practicable to provide for it in the Bill for tihs Act before that Bill was introduced into the House of Representatives

- This Act has effect as if Schedule 1 were amended, in accordance with a determination of the Finance Minister, to make provision for so much (if any) of the expenditure as the Finance Minister determines.

- The total of the amounts determined under subsection (2) of this section and subsection 10(2) of the Supply Act (No. 1) 2019-2020 cannot be more than $295 million.

- Subsection (3) of this section prevails over subsection 10(3) of the Supply Act (No. 1) 2019-2020.

- A determination made under subsection (2) is a legislative instrument, but neither section 42 (disallowance) nor Part 4 of Chapter 3 (sunsetting) of the Legislation Act 2003 applies to the determination.

Appropriation Act (No. 2) 2019-2020

12 Advance to the Finance Minister

- This section applies if the Finance Minister is satisfied that there is an urgent need for expenditure, in the current year, that is not provided for, or is insufficiently provided for, in Schedule 2:

- because of an erroneous omission or understatement; or

- because the expenditure was unforseen until after the last day on which it was practicable to provide for it in te Bill for this Act before that Bill was introduced in the House of Representatives.

- This Act has effect as if Schedule 2 were amended, in accordance with a determination of the Finance Minister, to make provision for so mich (if any) of the expenditure as the Finance Minister determines.

- The total of the amounts determined under subsection (2) cannot be more than $380 million.

- A determination made under subsection (2) is a legislative instrument, but neither section 42 (diallowance) not Part 4 of Chapter 3 (sunsetting) of the Legislation Act 2003 applies to the determination.