Ben Wellings

Introduction

When thinking about what I might about say in this lecture it occurred to me that it would be appropriate to look at parliaments and sovereignty, which are hugely important concepts when it comes to understanding Euroscepticism and Britain's place in the European Union (EU). I was particularly impressed—or scared depending on how you look at it—when I went over to the United Kingdom in July 2016, in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote, to do some research and it struck me that I could not really tell who was in charge. In that time after the Brexit vote when David Cameron had stepped down, Teresa May was not yet prime minister and, because of various back-stabbings and underhanded tactics, neither Michael Gove nor Boris Johnson nor Andrea Leadsom would be prime minister of the UK, I felt like that apocryphal Martian who arrives in London and says 'take me to your leader' to which someone replies 'well I'm sorry, I don't really know who that is at the moment'. However it was not just a question of leadership, it was also a question of which corporate body was in charge. Was the government in charge of the United Kingdom? Was parliament in charge of the United Kingdom? Were the people in charge of the United Kingdom? Where did sovereignty now lie? Brexit opened the opportunity for various different bodies to take back control not just from the EU but also from each other.

The Leave Campaign's quite ingenious three-word slogan, 'Take Back Control', can be read on all sorts of different levels. On one hand, it was about taking back control of local communities from foreigners, from immigrants. On the other hand, it was also read as a constitutional argument about taking back control from Brussels and restoring the full sovereignty of the Westminster Parliament. However, in the wake of the vote there were all sorts of grey areas which allowed various different parliaments, not just the Westminster Parliament, to take back control from each other. So first of all Brexit is not just the referendum vote of June 2016, but it is the politics of nationalist mobilisation leading up to that vote and it is also the politics of disengagement subsequent to that vote. So when I talk about Brexit I am referring to an extended period in the first three-quarters of this decade and extending back into the previous one. Brexit also opened up questions about sovereignty—post-sovereignty and good old-fashioned state sovereignty—and where different understandings of sovereignty might pertain within the United Kingdom itself.

This lecture will have the following structure. Initially I want to address the place of referendums in the British Political Tradition and how that relates firstly to popular sovereignty, which has quite a peculiar position in British political theory, and secondly to populism, a slightly newer, though not unheard of, phenomenon in British politics. In the United Kingdom Brexit is a peculiar expression of a populist moment happening around the world.

I will also break down the United Kingdom into its constituent components because that is a very important element in understanding Brexit. I want to look at the current UK government's understanding of sovereignty and what I am calling the 'new English unionism'. I should point out that 'unionism' in British political terminology has a different meaning to unionism in Australia. In the UK it is not about trade unions—rather it is about supporting the political union of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and in particular the really important relationship between Scotland and England. I will explore England's place in this moment of Brexit and then look at the devolved administrations—Scotland, Wales and London. Scotland is the most salient and important of these instances because it has the greatest autonomy from Westminster.

Then I will discuss sovereignty, Brexit and the border shared by the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland in the province of Northern Ireland. It is with the Republic of Ireland that the United Kingdom has a land border with the EU. Questions of sovereignty are especially pertinent in that part of the United Kingdom.

Lastly, I want to focus on parliament itself. By parliament I mean Westminster and in some ways I am reflecting my English bias because there are many parliaments in the United Kingdom now. That fact has not always percolated down or up, depending on your point of view, to Westminster and to the English electorate more broadly. Nevertheless, Westminster still has an important position in the United Kingdom and, for reasons I will explain later, I refer to it as the 'squeezed middle' as a result of Brexit.

Brexit and the pluri-national United Kingdom

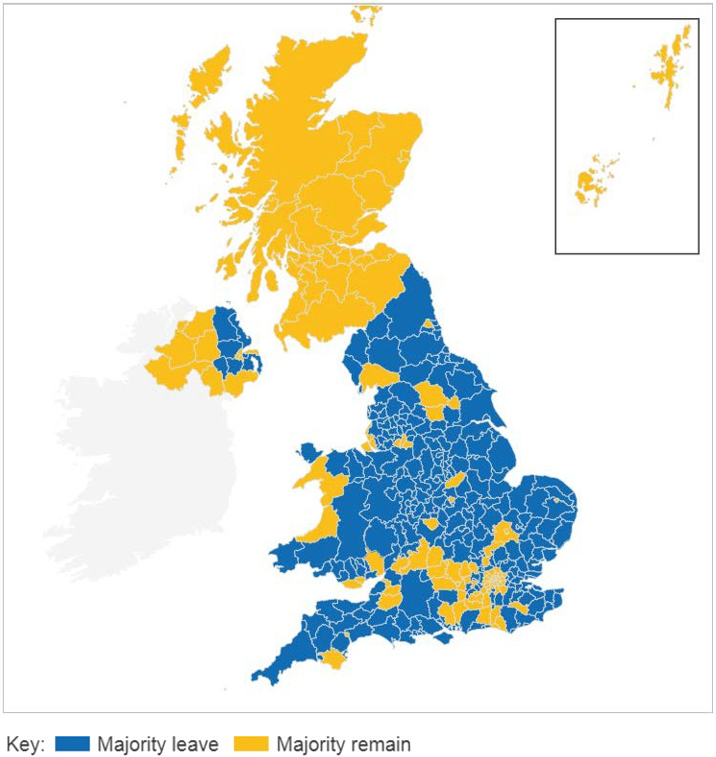

Figure 1 shows the distribution of support for Leave and Remain in the 2016 Referendum. The yellow is Remain and the blue is Leave. It brings out starkly the national differences the Brexit referendum threw light upon. What stands out most obviously is Scotland—the voting preferences and the area covered by Scotland overlap. It will come as no surprise that Northern Ireland is divided and that cleavage fell very closely along sectarian lines. The picture is a little more problematic and dispersed when you get into England and Wales, but England outside of London was predominantly for Leave.1

Figure 1: How the UK voted in the Brexit referendum. Courtesy of the BBC

This illustrates important national differences which were evident in the nationalist mobilisation that took place up to and before the actual vote itself. In the two decades before the Brexit vote there had been a process of embedding devolved administrations throughout the United Kingdom, including in Scotland, Wales and London, Northern Ireland and more recently in some north-western regions of England. However, the UK is not a federal structure but a devolved one where, until as recently as 2016, notionally Westminster could rescind the powers of any devolved assembly. We might call the UK a 'quasi-federation' which is in the process of removing itself from another quasi-federation, the European Union. These different moving parts opened up a lot of grey areas within British politics. A colleague of mine who is a legal scholar once told me that you are not a good lawyer if you can't exploit the grey areas. I think that this is true in politics as well; you need to be able to exploit those grey areas, and that is what Brexit has enabled. Brexit has deepened these divisions and opened up political opportunities for actors within these institutions and polities. In this sense Brexit represented a moment where key actors sought to 'take back control' not only from the EU but from each other too.

Referendums and the British Political Tradition

Since 1997 referendums have become a feature of British politics, especially when associated with constitutional reform. Until that time, referendums were not common in British politics, but since the election of New Labour in 1997 they have been conducted with increasing frequency. In 1997 referendums were used to endorse the decision to establish or re-establish a parliament in Scotland and an assembly in Wales. There was a second referendum on Wales in 2011 that increased the legislative powers of the National Assembly for Wales. In 1998 referendums were held in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland ratifying the Good Friday Agreement. In 2004 there was a referendum in the North East of England on whether there should be a regional assembly, with the electorate voting overwhelmingly 'no' by a margin of 78 to 22 per cent. Lastly, there was, of course, the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 and in 2016 the EU referendum itself.

So you can see that something has changed in the nature of British politics in that there is this increasing recourse to the device of a referendum. Often referendums are used as a de facto endorsement of decisions that have already been made. The 1997 referendums were a case in point. The New Labour government had already decided to devolve powers to Scotland and Wales but referendums were deployed to give that decision extra legitimacy and act as a bulwark to the powers being rescinded by any future Conservative government. An important, unintended consequence of this use of referendums is that they have become a bulwark against the re-extension or the reclamation of powers by Westminster in these devolved areas.

Something else to note are the occasions on which referendums did not occur. Over the last 20 years these have included the non-referendum on the United Kingdom joining the euro in 2003 and the referendum on the draft Constitutional Treaty of the European Union, which the UK avoided in 2005 because the French and Dutch electorates had already rejected the Treaty. The point here is that sometimes simply threatening to have a referendum is enough to derail a course of political action or proposed policy. In those two instances the implied notion was that the public was so Eurosceptic they would reject these initiatives anyway. In hindsight that notion was probably correct enough to make conducting a referendum a high-risk political venture.

However, all this political activity around referendums masks the fact the device was a novelty in British politics. I am referring to UK-wide politics here because there are local instances of referendums, even in the 19th century. For example, in the 19th century there were local referendums on establishing public libraries. In 1946 the people of a town called Stevenage in Hertfordshire had a referendum on whether they wanted a 'New Town' built next to them to accommodate people from London as part of the solution to the postwar housing shortage. They voted to reject Stevenage New Town. A series of referendums were held in Wales in 1961 on whether to rescind a ban on Sunday drinking. Some areas voted to rescind the 1881 prohibition and other areas voted to retain it with the result that as late as 1996 there were dry and drinking areas in Wales. Then there was the so-called 'border poll' in 1973, which asked voters in Northern Ireland whether they wished Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom or to join the Republic of Ireland. The result was 98 per cent in favour of remaining in the United Kingdom, but the nationalist community boycotted the vote. Questions of participation are important here and whether referendums assume a settled definition of the people whose will the vote is supposed to reflect. The first UK-wide referendum was held in 1975 and was on whether the UK should remain a member of the European Economic Community, or Common Market as it was then commonly known.

The outcome of the Stevenage referendum noted before—the new town was built anyway despite objections—gives some sense of the principal problem of referendums in British politics. If you believe and uphold the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty then referendums in British politics can technically only ever be advisory. The principle of parliamentary sovereignty says that no parliament can bind its successor. It asserts that there is no higher authority than parliament in the United Kingdom and therefore joining the European Union problematised that particular understanding of sovereignty. When the 1975 referendum on the Common Market took place it opened up an alternative source of authority in British politics that was not parliament. It was 'the People'. That might sound strange in a democracy—and of course elections have an inbuilt notion of popular sovereignty— but there was a very strong strand in British politics that was a mixture of Tory paternalism, Labour welfare statism and a civil service 'Sir Humphrey'-like steering from Whitehall that added up to an attitude of 'government knows best'. It was a view that the United Kingdom existed under what in 1976 Lord Hailsham, former Lord Chancellor of the United Kingdom, called an 'elective dictatorship'. That is to say, every four or five years the electorate votes enormous powers to the executive government via parliament and the executive government rules with great leeway for action until the next election comes around.

There are some subtle differences to the Australian situation where the notion of sovereignty is built into section 128 of the Constitution, which provides that any proposed change to the Constitution must be endorsed by a double majority of states and electorates at a referendum. By contrast, in the United Kingdom constitutional change does not automatically trigger a referendum. Rather, a referendum is a political decision. The postal ballot on marriage equality held in Australia in 2017 is the closest analogy to the way referendums come about in the United Kingdom. When party leadership loses control of an issue and can no longer mange it through conventional means, the issue is then presented to the electorate as a matter of either conscience or supreme national importance that must be decided by 'the People', who are suddenly constituted as a source of authority above that of the politicians and the executive government.

In 1975, when Harold Wilson decided to implement a referendum on Britain's membership of the Common Market, he borrowed heavily from Australian practice. As an aside, one thing he opted not to do was use computers to count the vote because he felt they were unnecessary—and so the votes were counted by hand! The reason the issue of the UK's membership of the European Economic Community went to a referendum was because the Labour Party, which was in government, was so irrevocably split on the Common Market, both in the cabinet and between the leadership and rank and file, that the pro—or at least agnostically—European leadership decided to put this to 'the People' rather than risk a damaging party split. There was a two to one vote in favour of staying in the Common Market, but concerning popular sovereignty the cat was out of the bag. The 1975 referendum set a precedent that 'the People' needed to be consulted on an important constitutional matter such as this. When the Labour Party came back to power in 1997 it adopted this model of using referendums as a means of endorsing constitutional change that had already been decided upon.

Fast-forward to the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government of 2010–2015. Through the European Union Act 2011 (UK), the government built in the necessity for a referendum on any future transfers of power ('competencies' in EU parlance) from Westminster to the European Union. At the time this innovation was called a 'referendum lock' and it was designed to halt the further extension of EU powers over the United Kingdom. If the European Union wanted to increase its competencies over the United Kingdom, then the United Kingdom government was—in certain circumstances—obliged to hold a referendum to gain popular consent. Potentially that meant a lot of referendums. However, there was the caveat that what represented a fundamental transfer of competency would be a political decision based on the government's interpretation of the powers to be transferred. Nevertheless it built into the British political system an explicit place for referendums that had not been there before.

As Emma Vines and I tried to make the case when analysing the European Union Act,2 this had the unintended consequence of undermining that which it sought to protect. The idea behind the Act was to use a referendum to protect the sovereignty of Westminster from further competences the European Union might try to extend over the United Kingdom. However, what it did was open up an alternative source of authority or sovereignty by building 'the People' and the referendum device into the British political system itself. In the years after 2010 it was also an attempt to manage the growing rise of popular discontent toward both the British political class and the European Union, particularly in the wake of the global financial crisis and the parliamentary expenses scandal of 2009. This kind of populist revolt was exemplified by the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and its erstwhile leader Nigel Farage. His speech to the European Parliament in June 2016, five days after the referendum, illustrated the populist element in British Euroscepticism.3 He said:

What happened last Thursday was a remarkable result, it was indeed a seismic result, not just for British politics, for European politics but perhaps even for global politics too because what the little people did, what the ordinary people did, what the people who have been oppressed over the last few years and see their living standards go down—they rejected the multinationals, they rejected the merchant banks, they rejected big politics and they said, actually, we want our country back, we want our fishing waters back, we want our borders back, we want to be an independent self-governing, normal nation and that is what we have done and that is what must happen.4

Farage was pitting the 'little' and 'ordinary' people against not only the European Union but also the pro-European political class in the United Kingdom. This shift stemmed from notions of popular sovereignty and populism. Drawing on Professor Cas Mudde's work, populism is slightly different from established party politics because it suggests that basically conflict in society is between a pure people, who are expressive of the general will and all kinds of virtuous values in the political community, and an elite who have been corrupted through their proximity to power, either in a direct sense by lining their own pockets or indirectly through too much proximity to vested interests that are beyond the reach of democratic control.

5 Populism is a slightly difficult ideology, if we want to call it that. It is not necessarily formed as a coherent set of ideas to frame political action but it is an expression of political resentment. Confusingly it has some overlap with the concepts of democracy, nationalism and nationhood, all of which also place 'the People' at the centre of their political worldview. In the United Kingdom context it opened up an important question—if 'the People' are sovereign, which 'People' exactly are we talking about? If you seek to express a general will through a referendum device it assumes that you know who or what the political community is, or indeed that one exists. As Brexit illustrated that was not necessarily something that could be taken for granted in the United Kingdom in 2016.

Brexit and the 'new English Unionism'

This leads to the government's position and what I am going to call for now the 'new English Unionism'. I have suggested before that the politics of nationalist mobilisation complicated the understanding of the United Kingdom as a single political community. When Theresa May said in the wake of Brexit that 'we voted to leave the European Union as a single United Kingdom and therefore we will leave the European Union as a single United Kingdom' she was making a claim rather than reflecting a settled political reality. That claim was an attempt to take back control from other parts of the kingdom whose governments were, and are, seeking to defend and extend their own autonomy even to the point of secession from the UK. When Theresa May came back from Buckingham Palace on 13 July 2016, having accepted the Queen's invitation to form a government (another source of sovereignty in the United Kingdom), the first thing she did, other than thank David Cameron for being a terrific prime minister, was defend the English version of the Union. She did not immediately highlight leaving the European Union. If we take the way her speech was constructed as an indication of political priorities, maintaining the United Kingdom was a greater priority to her than leaving the EU. In her speech, May said 'not everybody knows this, but the full title of my party is the Conservative and Unionist Party, and that word “unionist” is very important to me'. She continued:

It means we believe in the Union: the precious, precious bond between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. But it means something else that is just as important; it means we believe in a union not just between the nations of the United Kingdom but between all of our citizens, every one of us, whoever we are and wherever we're from.6

What she was trying to do was talk not just about the political union of the United Kingdom but the social divisions opened up by the distribution of votes for Remain and Leave across the United Kingdom, but especially in England. When Theresa May told voters that the United Kingdom was 'precious' to her, this was a southern English Conservative prime minister defending an English version of Britishness. This defence of British sovereignty is one version of what I have called elsewhere 'English nationalism'. If we attempt the difficult task of disentangling England from Britain, the Leave campaign's version of English nationalism, which was characterised by the desire to defend British sovereignty, is an example of a conflation between England and Britain in political ideology and rhetoric.

This statecraft returns us to Brexit as a three-level game—extracting the UK from the EU, seeking alternative or 'traditional' allies outside of the EU, whilst keeping the United Kingdom together. The Conservatives, who until 2017 were very much the 'English party' by deed if not by name, were now playing a double game with England. England was crucial to understanding the vote to Leave, but it was also crucial if the Conservatives were to keep the United Kingdom united because if the English stopped believing in the United Kingdom then there would be trouble. This UK government perspective, which by virtue of its support within the Conservative Party becomes de facto 'English unionism', was a very English conception of United Kingdom's sovereignty as singular and unified. Despite political developments discussed below, it still assumed that Westminster could rescind the devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales in the same way as it has done in Northern Ireland, although for very different reasons. If this power was enacted it would be very provocative and inflammatory. Although technically possible, it was and is politically impossible, even before the developments in Scotland and Wales discussed below.

Brexit and the devolved administrations

Now you can imagine how that kind of understanding of sovereignty is received in Edinburgh and Cardiff. It sets alarm bells ringing. Predictably it was resisted by the devolved administrations, both the Scottish National Party administration under Nicola Sturgeon and the Welsh Labour administration operating in Cardiff under Carwyn Jones. The reason that there is this disjuncture here is because the notion of the British constitution—remember I am not referring to a written document but to an accepted way of doing things sometimes characterised as a 'customary constitution'— has been steadily challenged by changes in Scotland and Wales since devolution in 1999 and the way that has bedded down. This change has not been well understood or recognised in Westminster or Whitehall despite the Scotland Act 2016 (UK) and the Wales Act 2017 (UK).

Thus as Britain comes out of the EU we have different and competing understandings of sovereignty operating within the United Kingdom. In Scotland these differing conceptions of popular sovereignty have existed for a long time. In reverse order, there have been so-called 'Claims of Right' made on behalf of or by the Scottish people in 1989 after the imposition of the poll tax, in 1842 in relation to problems in the Scottish Kirk, and even in 1689 after the 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688. As I noted, this reality has gone little noticed in Westminster or Whitehall, even by Downing Street, but it is an established way of understanding sovereignty in Scotland. A good expression of this was when the Scottish Parliament opened in 1999 and Winnie Ewing, who as the oldest member of the House chaired the opening session, made the point that this was a reconvening of the Scottish Parliament which had not met since 1707 rather than an establishment de novo. She said 'I want to start with the words that I have always wanted either to say or to hear someone else say – the Scottish Parliament, which adjourned on March 25, 1707, is hereby reconvened'.7 So if you think that Australian parliamentarians do not meet often enough, then three centuries is extreme! The point Ewing was making by referring to this as a reconvening of the Scottish Parliament is that it had been in abeyance since 1707 and now it was back. So what in London was seen as a constitutional innovation, in Edinburgh was seen as a restitution.

The Scots had their own independence referendum in 2014 which was another way of 'taking back control', in this instance from Westminster, even if the idea was to retain a measure of oversight from Brussels within the European Union. However, the fact that the English majority at Westminster agreed that a referendum should take place and that the result should be respected regardless of the outcome, seemed to suggest that the United Kingdom was now a voluntary union and the idea that it was unitary had broken down. The 'Catalan option', if I can call it that, was technically possible— London could have done what Madrid did and just declare the referendum illegal and ignore the outcome, but the fact that it did not do this fits into notions of incrementalism in British politics. Despite this, the idea that Scotland was somehow different did not enter very strongly into the official thinking of Theresa May's government. May's method and means of getting the UK out of the EU involved a reassertion of the UK government's control over Scotland.

Yet the Scotland Act reasserted that the devolved parliament cannot be rescinded without recourse to a referendum in Scotland. The Wales Act mimicked the Scotland Act in stating that the National Assembly for Wales, or Senedd, could not be rescinded without a referendum. Here again the sovereignty of the Welsh and Scottish people was now a bulwark against the extension of executive control over the United Kingdom. We are now waiting for the possibility of another referendum on independence in Scotland as and when the terms of the Brexit deal are announced. I am not sure if that would be an easy thing for the Scottish National Party to win despite the very pro-EU vote in Scotland in 2016. Then there is London that is very connected to the European Union. This might be an apocryphal story but they do say that London is France's seventh most populous city because of the number of French people who have moved to London to work. The London administration is very unfavourably disposed towards Brexit but it does not have the strength and the autonomy that the Scottish Parliament has.

Brexit and Northern Ireland

This leads to perhaps the most difficult and contentious part of Brexit and the kind of shared sovereignty that operates in the UK. The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland—which is to say the land border between the United Kingdom and the European Union—is the hardest square to circle in the Brexit negotiations. This is partly because there is a fear that reimposing a physical border in Ireland will reignite 'The Troubles'. The Good Friday Agreement, which just had its 20th anniversary, brought an uneasy truce to the province but the government of Northern Ireland has not sat since January 2017 and Westminster is applying 'direct rule' in Northern Ireland. The difficulty that comes in the negotiations is because in December 2017 it was agreed that there would be no restitution of a hard border in Northern Ireland as part of the Brexit deal. On the other hand, it was also stated that Britain would not be part of the Single Market. At the moment those two things seem to be contradictory. The question is what happens to Northern Ireland? Where will the border of the United Kingdom start and stop, on what side of the Irish Sea will the United Kingdom border be located? If Northern Ireland remains within the Single Market, or even enters into a customs union with the EU, it effectively means Northern Ireland is not as much a part of the United Kingdom as it once was.

So here there are all sorts of overlapping sovereignties. This is not just a question of the United Kingdom and Westminster dealing with a devolved assembly. To some extent the Republic of Ireland has a say in the governance of Northern Ireland and the European Union used to have a lot of say in the governance of Northern Ireland. All these things are in the 'grey areas' that are coming apart in the Brexit negotiations. The British government is not keen on losing Northern Ireland, although the constitutional position in the Good Friday Agreement is that if there is a referendum in favour of Northern Ireland leaving the United Kingdom the result will be honoured. Presumably Northern Ireland would leave to join the Republic of Ireland but I am not sure how keen the Republic of Ireland would be about that.

However, the British government position is that it will not lose Northern Ireland. On 29 March, one year after the triggering of Article 50,8 Teresa May pledged to defend the integrity of the United Kingdom, which she described as the world's most successful union. She said there was no way we would break that up. On the other hand, a YouGov poll, commissioned by radio station LBC exactly one year before Britain was due to leave the EU, found that overall most people in Britain would prefer to leave the EU than keep Northern Ireland in the UK. Sixty-one per cent of voters who claim to have voted Conservative in 2017 said they would rather leave the EU than retain Northern Ireland. Seventy-one per cent of people who said they voted for leaving the EU in 2016 said they would rather leave the EU than retain the United Kingdom.9 The ensuing headline that the majority of 'Brits' wanted to abandon Northern Ireland obscured the Englishness of the poll. For Scots it was notably different. The poll found that more Scots wanted to keep Northern Ireland in the UK than leave the EU. So this was an English response.

Having looked at the devolved administrations, I want to return to the importance of England. England is crucial to what happens in Brexit and for that reason I want to argue that the idea of a 'new English Unionism' is not quite right. It is clear from the language she uses that Theresa May is referring to a form of Unionism that has its roots and wellsprings in England, particularly in southern England. However, if we take the YouGov poll as evidence that the strength of being British is weakening, then the Union that Theresa May says is so precious to her is actually degrading. Although we think of Euroscepticism as a British phenomenon, it is by and large an English phenomenon. In polls where people are asked what nationality they think they are and that response is then linked to their attitudes towards European integration, most people who self-identify as British are pro-EU and most people who identify as English are anti-EU. So the idea of England is crucial to this.

Westminster: the squeezed middle

Throughout this Westminster Parliament was the 'squeezed middle'. One of the great 'left behinds' of the Brexit vote was the parliament. Firstly, parliament was sidelined by the popular sovereignty implicit in the vote and the referendum device and the populism of the campaign and its aftermath. At the same time, in the wake of Brexit, parliament was also sidelined by the executive government's desire to take back control from various administrations and its interpretation of the popular vote as giving it a mandate to get out of the EU without having to seek recourse to parliament. This was challenged by various MPs, including Labour MP David Lammy from Tottenham, who is a strong believer in the principle of parliamentary sovereignty and was particularly vocal in saying the referendum was only advisory and parliament should have a vote on whether to leave the EU or not. That might be technically correct but, as I have said before, it is politically inflammatory and parliament was not able to do it.

There was also a challenge put in the UK High and Supreme Courts and the High Court initially voted that parliament should have a say on Brexit. Initially the government wanted to use the Royal Prerogative to leave the EU. The Royal Prerogative is a measure used to declare war or permit conflict with other states, for example Britain's involvement in Syria. The High Court decided that using the Royal Prerogative to get out of the EU was not compatible with the British constitution. For their troubles, the Justices of the High Court were labelled 'enemies of the people' by the Daily Mail for not upholding its interpretation of the popular will. Yet it is important to point out that in claiming a democratic mantle, the Daily Mail is not a democracy itself—no one voted for the editorial board of the Daily Mail. I am using this as an indication of the way parliament was squeezed between popular sovereignty, populism and executive authority. Of course parliament now has the right to have a so-called 'meaningful vote' on Brexit. It is not clear how meaningful that vote can be once the Brexit deal is known in October. Remember before the vote parliament was pro staying in the EU and it is not really clear how much time parliament has or how much authority it can bring to bear on the negotiations, which are like a large ship coming into port—it needs a long time to stop or turn around. While a measure of voice has been given to parliament, Westminster is still one of the great left behinds of the whole Brexit episode.

Conclusion

So if we understand Brexit as not just narrowly the referendum on Britain's membership of the EU in 2016 but we think of it as an ongoing politics of nationalist mobilisation, before and after the referendum, it represents a moment where key actors sought to take back control, not just from the European Union, but from each other too.