Desmond Manderson

Myths and stories

I am not one of those Magna Carta minimisers. So important do I consider it that I would go so far as to say that it is the second most important legal document produced in 1215. But what, one may ask, of the document that beats it into second place? How is it different and more to the point, how do the two texts shed light on each other?

It is often said that Magna Carta has 'become' a myth. This is not so. It was a myth right from the start. As Sir Edward Coke used the charter as a symbol of ancient liberties against the Stuarts, so the barons already appealed to the 'ancient laws' in their battles against King John. Magna Carta, and the barons' Charter of Liberties on which it was based, already recalled the Coronation Oath of Henry I for its authority. The Coronation Oath in turn harked back to the laws and liberties of Edward the Confessor. So Magna Carta already appealed to a mythic time of ancient liberties. If some of its textual ambiguities were responsible for the short-term failure of the charter, these same ambiguities and the gloss of myth that covered them were equally responsible for its long-term success. All myths are indeterminate enough to mean different things at different moments, concealing legal and social change under the patina of tradition.

But the greatest of all the myths that surround Magna Carta is the myth of exceptionalism. Scholars as wide-ranging as H.E. Marshall or R.F.V. Heuston—not to mention Margaret Thatcher—belabour the supposed Englishness of the rule of law. In a celebrated cartoon like Thomas Rowlandson's 'The Contrast' (figure 1), published in 1792 at the height of British reaction to the French Revolution, Magna Carta is held up as the feature that distinguishes British liberty ( 'loyalty, obedience to the laws ... justice') from the French kind ( 'treason, anarchy, murder, equality [!], madness, cruelty, injustice'). Or there is Rudyard Kipling:

And still when Mob or Monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

The whisper wakes, the shudder plays,

Across the reeds at Runnymede.

But Magna Carta was not so exceptional. English law was part of a pan-European legal culture, bound together by a common religion and a common cultural language, which saw a constant traffic in legal ideas in different places, and between canon and civil law. England was more connected to continental trends and currents than at any time since (at least, one might say, until the European Court of Human Rights). The struggle between the power of kings and the limits on those powers was everywhere manifest in thirteenth-century Europe. Hungary's Golden Bull (1222) and Simon de Montfort's Statute of Pamiers (1212) are but two examples of similar documents produced around the same time as Magna Carta. All seek to lay down explicit limits on the prince's ability to ignore or make new law as he saw fit. And all connect the appeal to justice to a return to a golden age, often located in the time of our grandfathers: that is, on the very border between remembered stories and verified facts. This has always been the function of grandparents. They are the bearers of myth, from their childhood to ours, the last physical, tangible links in the chain of inheritance.

Figure 1: 'The Contrast 1792. British Liberty. French Liberty. Which is best?' by Thomas Rowlandson.

Hand-coloured etching, British Museum, London, J,4.50 © The Trustees of the British Museum

A delicate balance

References to previous Coronation Oaths, or to the laws of our grandfather's day, formed a narrative connection between past and present. This was important because of the function of narrative in late medieval thought, which in all fields of intellectual activity, was essentially proverbial and textual. It operated horizontally between texts, rather than vertically from authority to subject, or from principle to example. It operated by way of resemblance and comparison rather than by distinction and hierarchy. In this way, commentators and critics (as we might call them now) shared an equal authority with the authors they commented on. Gratian's synthesis of canonical texts in the twelfth century in the Decretals, itself a complex synthesis of prior sources, gave rise to a whole host of glosses and discourses, and so on ad infinitum.

Textual analysis was unending, discursive, disputatious, referential, and rhetorical. While adages such as princeps legibus solutus est (the prince is loosed from the laws), or 'what pleases the prince has the force of law' were important themes in medieval jurisprudence, it is a mistake to take them at face value. It was in the much later context of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that the doctrine of the divine right of kings took these flights of medieval rhetoric literally. In the late Middle Ages, the claims of the prince were constantly balanced by norms of responsibility and justice. Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190) famously asked his scholars, 'am I lord of the world?'—but the short answer was no. A close reading of the great glossator Accursius (1182–1263) discloses that, for him, the question of princeps legibus solutus est is not whether the prince is entitled to act arbitrarily—he is not—but whether any mechanism can hold him to account.

Where the baroque world was in love with power, the medieval world was in love with balance and with subtlety. Indeed the unique pluralism of medieval society is, as Brian Tierney argued, the true origin of the rule of law. Feudal law was essentially constituted by divided and independent sources of power: the canon law of the pope on the one hand, and the Roman law of the emperor on the other. But these 'two suns', as Dante had it, were themselves internally divided. Bishops and the church on the one hand, and princes and lords on the other, claimed in certain areas an independent authority granted directly by god, and not a delegated or subordinate one. To this must be added the normative force of local customs, in some cases extending back to pagan times.

This 'fertile jurisgenesis', as Robert Cover would have it, provided the soil in which the medieval genius for new and semi-autonomous legal communities could take root. Universities, monasteries, guilds, cities and corporations all flourished as entities with distinct legal personalities. It became habitual to think of a distinction between a person's interests and their role, between their own power and the body or corporation on whose behalf they were acting. This gave rise to two critical legal concepts, whose origins and importance Shaun McVeigh has insisted on for many years. The first was the idea of 'office', which replaced the personal basis of feudal relations with abstracted responsibilities of which the office-holder is only the custodian. As Ernst Kantorowicz argued, 'the fisc', 'the Crown', and 'the patria' are all abstractions whose emergence creates a distinction between the prince and the body corporate or politic. The second was the idea of 'jurisdiction', the necessary complement of a pluralist system in which lines of authority must be constantly drawn and redrawn. But with jurisdiction, says Tierney, comes the concept of a right; for what is a right but a claim that appropriating or depriving one of some good, is ultra vires a particular authority. The limit of a jurisdiction is the birth of a right. The notion of the office allows those rights to be asserted on behalf of an abstract community, against even the prince.

The legal Reformation

But in the twelfth century a new wind was perturbing this delicately balanced system. Harold Berman famously said that law was the first science of the West. Law developed, over time, into a system based on known principles, applied on the basis of hypotheses empirically tested in court through cases. But if law was the first modern science, the first modern law was, ironically, the Catholic Church. Most notably in the course of the Papal Revolution or Reformatio initiated by Gregory VII's Dictatus Papae in 1075, the pope claimed absolute authority over the church and independence from all secular authority. As part of this explicit separation of church and state, canon law began to take on the characteristics of a coherent and internally independent legal system, along with the power to create new laws enforceable throughout the pope's jurisdiction. This radically changed the style and functioning of law in the church. It replaced notions of reason and justice with sovereign will. It made the legitimacy of law a question not of its content or its source but its form—in Laurentius' articulation of this logic in 1215, the first glimmerings of legal positivism can be discerned. And in contrast with earlier concepts of law in medieval Europe—law as custom, folk law, natural law, or divine law—ius novum was understood as made by man, though not of course just any man.

The church was not modelled on the State. On the contrary; the State was modelled on the church. This profound change in the concept of law inaugurated radical changes in law's functioning and purpose all over Europe. As Pennington put it, the role of the ruler changes from being the 'guardian' of the law, to its 'authors'.

For the kings and princes, particularly of the Norman kingdoms, began to see the potential of this technology to transform how they did business. It turned the key function of kingship from a military to a legislative and administrative one: changing behaviour by changing laws. Law becomes temporal rather than spiritual, a positive and wilful act. It becomes related not to the conquest of land but the conquest of subjects. And it requires a whole phalanx of new professionals to devise and supervise this complex system. In the centuries between Gregory's legal reformation and Luther's religious one, a new class of clerics, clerks, lawyers and judges serve as the vanguard of modernity and, in the words of one later commentator, 'a guild of sovereignty-mongers'.

The English experience conforms to this pattern. The Angevin reforms of the twelfth century—the justice in eyre that brought a coherent system of law to the whole country, the development of the writ system to determine jurisdiction, the assizes that changed the law, the jury system that applied it, and the plea rolls that recorded it—all speak to a passion for administrative efficiency, regularisation, and law-making as a principal function of government. Henry II (1133–1189) was one of the great Norman pioneers of the instrumentalisation, centralisation, and bureaucratisation of law. King John's problem, or one of them at least, was that he was no Harry Plantagenet. He applied these modern legal methods with gusto, but then fell back on extorting exactions to pay for his European ventures through the old ways of arbitrary and personal government. He applied the law to others but not to himself. The struggle that led to Magna Carta is often described as a rebellion by the 'Northern barons'. No wonder. Because he was vigilant and itinerant, imposing his will up hill and down dale, it was the northerners that suffered the most; they were used to being left alone.

Thus Magna Carta responds to the developing modernity of kingly rule. It appeals to ancient rights and privileges, and to the pre-existing fabric of often tacit constitutional checks and balances. What is interesting is that it does so using the techniques and methods of the Angevin reforms itself. It seeks the surety of the king by securing his assent to a set of written and explicit rules. It evokes a corporate model of social organisation in which the king is subject to the laws of the land and not 'loosed' from them. And overall, although there are of course specific rights and liberties contained in Magna Carta, the document focuses on the consistent and predictable application of procedure. By and large it accepts the Angevin reforms, insisting only that the Crown should be held to the same standards of regularity and consistency that King John demanded of the barons.

Due process

The development of the interest in 'due process', which is given an early formulation in article 39 of the original version of the charter and which was to become a central element of the rule of law, was a reflection of the new priorities of the reformed legal system—its positivist, temporal, instrumental, textual, semantic, evidential orientation, accompanied by its interest in questions of office and jurisdiction. If the king can make law out of his own will, then the question is no longer what law, but how. And this gives to questions of procedure and consistency a wholly new importance.

A crucial moment in the development of due process, both as an area of legal concern, and as a forum for the protection of rights and interests, was the decline in trial by ordeal, or trial by combat. The empirical, rational, and evidential orientation of the reformed legal system had already made dramatic inroads into these earlier modes of proof in the twelfth century. These trials operated on the assumption that in the right place, divine judgment would be manifested. Once manifested, as the expression of divine will, it could of course hardly be disputed or appealed. But once law is understood to be a human construction, the question of proof becomes the main problem of the legal system. Absent an expression of divine will, how is evidence to be gathered? How is proof to be assessed? By whom? These questions open up the whole field of due process, which is precisely concerned with the gathering and evaluation of evidence in a world in which the intervention of the divine could no longer be presumed. And of course, since humans err, due process must envisage the possibility of mistake, appeal and correction: a whole structure of courts and review mechanisms that had previously been inconceivable. The rule of law is tightly connected to the concept of due process, and due process itself is a function of the translation of law, and above all of questions of evidence and proof, from the spiritual to the temporal realm. None of this makes any sense in a world governed by divine intercession in the form of trial by ordeal.

And 1215 was the year it ended. This was accomplished not by Magna Carta, but the Fourth Lateran Council. Convened by Pope Innocent III, it prohibited the involvement of any members of the church in trial by ordeal and mandated the implementation of the ordo iudiciarium—that is, a legal and judicial process—wherever the church's writ ran. But the implications of this extended far beyond canon law. In any jurisdiction, spiritual or temporal, trial by ordeal required the participation and approbation of a priest. But after 1215, no member of the church could take part. It is true that trial by ordeal had been in marked decline over the previous century. But the blanket withdrawal of the imprimatur of the church was the last nail in its coffin.

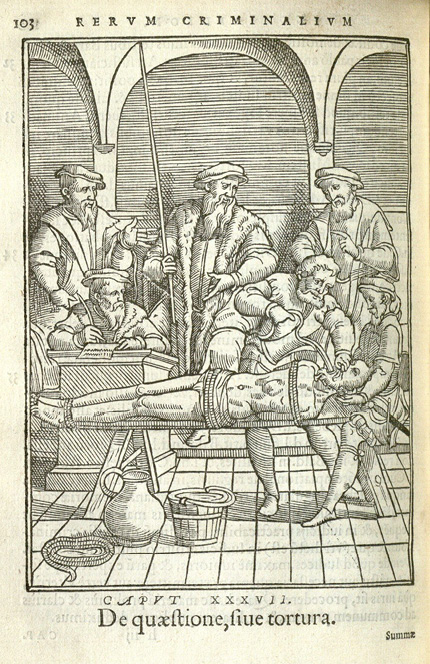

Figure 2: Woodcut from a Flemish legal text, Joost de Damhoudere's, Enchiridion Rerum Criminalium (Praxis Rerum Criminalium) (Louvain, 1554), p. 103. Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School

The problem of procedure and evidence in the absence of the immanence of divine judgment hereafter became the characteristic problem of modern law. Law was no longer a forum for the determination of truth, but rather for the weighing of proof. And on this point, it must be said that there does appear to be a distinction between the direction taken in much of Europe, and in England. The problem of human judgment led to a rise in torture. Torture is not an atavism, but in fact a consequence of law's early modernisation, of its being the first science, born in the middle of the Middle Ages. Proof was the problem and confession was the solution. Torture was conceived as a way of securing the best evidence possible for the commission of a crime. As such it became a normal part of criminal procedure right up until the seventeenth century.

This was never the case in England. Although torture by the State or the Crown was not unknown, it was never a recognised part of the legal system. The reason for this was simple. The Angevin reforms in the twelfth century had instituted and expanded the system of trial by jury. Until 1215, this continued in parallel with the older forms of trial by ordeal, or trial by combat introduced by the Normans. After 1215, trial by jury became, of necessity, uncontested. It put in place an empirical structure for the ascertainment of law and proof, connected to the participation and experience of a local community. In this way, an alternative to the model of torture and confession was available that was conformable to modern expectations of process, human judgment, and empiricism. Trial by jury was a form that was able to adapt old practices to the expectations of the new legal order. It operated like a myth, indeterminate enough to mean different things at different times, concealing legal and social change under the patina of tradition. Again, Magna Carta makes explicit reference to the jury, but we equally owe its success to the deliberations of the Lateran Council, that other 1215.

1215

Nonetheless, Magna Carta was an unusual document. Its reference to the separate corporate identity of the 'realm' or 'kingdom' or 'free men', to which the king was responsible—and even (at least in the 1215 version which did not long survive) accountable— 'acknowledged', as J.C. Holt wrote, 'non-baronial interests far more than most of the continental concessions and it covered a wider range of such interests more thoroughly'. The logic of reciprocity and of consistency of law-directed behaviour goes much further. But what makes it particularly significant, as a sign of the times, is its forms and tenor. These reflect in every paragraph the changing modes of government in early modernity, and the changing role of law, rights and procedures. The barons responded to legal technology not just with a nostalgic appeal to the past but with more and better legal technology. Modern concepts of law were the arms-dealers selling the guns to both sides.

It is emblematic that Magna Carta was not an oath but a charter, and equally emblematic that it did not stay a charter but became a law. In this movement from personal promise and loyalty, to a loyalty to the realm and to the law, lies the shift in the meaning and power of law that had taken place between 1075 and 1215. Magna Carta is best understood in the context of the radical transformation in legal culture and consciousness taking place right across the continent. It is both an instrument of and a response to the impact of these modernising forces. 1215 was a significant moment in that history, which began much earlier and whose ramifications continue to be felt to this day. On the one hand, Magna Carta was a local manifestation of this continental shift. On the other hand, the ordo iudiciarium was an important step in ensuring the entrenchment and acceleration of these processes, whose effects were felt right across Europe. One 1215 was a symptom—the other was a cause.

Additional references

Berman, Harold J., Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1983.

Breay, Claire & Julian Harrison (eds), Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, British Library, London, 2015.

Carpenter, David, Magna Carta, Penguin, London, 2015.

Church, S.D., King John and the Road to Magna Carta, Basic Books, New York, 2015.

Conte, Emanuele, 'Roman law vs custom in a changing society: Italy in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries' in Per Andersen and Mia Műnster-Swendsen (eds), Custom: The Development and Use of a Legal Concept in the Middle Ages, Proceedings of the Fifth Carlsberg Academy Conference on Medieval Legal History, 2008, DJØF Publishing, Copenhagen, 2009, pp. 33–49.

Daniell, Christopher, From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta: England 1066–1215, Routledge, London, 2003.

Danziger, Danny and John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta, Touchstone, New York, 2005.

Dorsett, Shaunnagh and Shaun McVeigh, 'The persona of the jurist in Salmond's Jurisprudence', Victoria University of Wellington Law Review, vol. 38, no.4, 2007, pp. 771–96.

Foucault, Michel, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, trans. Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books, New York, 1973.

Garnett, George & John Hudson (eds), Law and Government in Medieval England and Normandy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994.

Hudson, John, The Formation of English Common Law, Longman, London, 1996.

Kantorowicz, Ernst, Selected Studies, JJ Augustin (Princeton Institute of Advanced Studies), Locust Valley, NY, 1965.

Kantorowicz, Ernst, The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theory, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1957.

McVeigh, Shaun, Jurisdiction, Routledge, London, 2012.

Pennington, Kenneth, Popes, Canonists, and Texts 1115–1550, Variorum, Aldershot, 1993.

Pennington, Kenneth, The Prince and the Law: Sovereignty and Rights in the Western Legal Tradition, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1993.

Poole, Austin Lane, From Domesday Book to Magna Carta, 1087–1216, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1951.

Tierney, Brian & Peter Linehan (eds), Authority and Power, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1980.

Tierney, Brian, The Idea of Natural Rights: Studies on Natural Rights, Natural Law, and Church Law, 1150–1625, Scholars Press, Atlanta, 1997.

Tierney, Brian, 'Natural law and natural rights: old problems and recent approaches', Review of Politics, vol. 64, no. 3, 2002, pp. 389–406.

Tierney, Brian, 'Natural rights in the thirteenth century', Speculum, vol. 67, no. 1, 1992, pp. 58–68.

Tierney, Brian, 'The prince is not bound by the laws', Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 5, no. 4, 1963, pp. 378–400.

Tierney, Brian, Religion, Law, and the Growth of Constitutional Thought 1150–1650, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1982.

Vincent, Nicholas, Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom, Third Millenium, London, 2014.