4 October 2022

PDF version [648 KB]

Ian Zhou

Economic Policy Section

Executive

summary

Derivatives are powerful financial instruments that play

an important role in the capital markets. If they are mispriced or

underregulated, they can amplify underlying systemic risks in the global

financial system.

In 2003 Warren Buffett described derivatives as ‘financial

weapons of mass destruction’. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis arguably proved

the truth of his words because mispriced derivatives contributed to the

systemic risks in the global financial system that eventually caused the

crisis.

The 2008 crisis prompted a comprehensive international

regulatory response, directed through the G20 forum (including

Australia).[1]

Since 2009 Australian regulators have been implementing the G20 reforms to

improve transparency in the derivatives market.[2]

Notwithstanding the G20 reforms on derivatives trading, some

analysts fear that major international banks are becoming too exposed to

mispriced derivatives once again.[3]

Furthermore, the strengthening of prudential regulations on banks (as outlined

by Basel III) meant that the banks might find it cheaper to shift risk using

derivative contracts.[4]

This has sparked a public debate on whether there is sufficient government

regulation of derivatives trading in Australia and other countries.[5]

As an open economy Australia is vulnerable to global risks that

could trigger a ‘liquidity

crunch’ or a reduction in international trade. This has implications for

legislative changes implementing the G20 reforms, the resourcing and

effectiveness of Australian regulatory agencies supervising derivatives trading

and Australia’s engages with international partners in monitoring the progress

of G20 reforms on the derivatives market.

Contents

Executive

summary

Glossary

What is a financial derivative?

Why do investors and firms use

derivatives?

What role do derivatives play in the

financial markets?

How did mispriced derivatives

contribute to the Global Financial Crisis?

Regulation of derivatives trading in

Australia

Derivatives trading in the 2020s

Conclusion

Glossary

| Acronyms |

Definition |

| AIG |

American International Group |

| ASIC |

Australian Securities and Investments Commission |

| CDO |

Collateralised debt obligation |

| CDS |

Credit default swap |

| CLO |

Collateralised loan obligation |

| MBS |

Mortgage-backed security |

| OTC |

Over the counter |

| TRS |

Total return swap |

What is a financial derivative?

A derivative is a contract between two parties that derives

its value from the performance of an underlying asset. The underlying asset can

be almost anything of value (most commonly commodities, stocks and bonds).

There are many types of derivatives. Traditional forms of

derivatives such as options and forward contracts (illustrated in the example

below) have existed for hundreds of years. Newer and more complex derivatives

such as collateralised debt obligations or credit default swaps have grown

enormously in recent decades, and now constitute a multi-trillion dollar

worldwide market.[6]

Why do investors and firms use derivatives?

Derivatives are risk management tools. Investors and firms

use derivatives primarily for two reasons:

-

to hedge against future price

movements, reducing uncertainty; or

-

to speculate on future price

movements, accepting greater risk exposure in exchange for the chance of

greater profit. [7]

Using derivatives to hedge

Derivatives can make future cash flows more predictable, so

many investors and firms use them to hedge against potential risk. In this

regard, using derivatives is like buying an insurance policy that protects the

investor against price uncertainty.

Hypothetical

example of using derivatives to hedge against risk

Andrew is a wheat grower and

wants to sell his wheat in two weeks’ time. The current market price is $5

per kilogram, but it fluctuates daily.

Andrew makes a ‘forward’

derivative contract with wheat buyer, Ian. The contract stipulates that Ian

will buy 100 kilograms of wheat from Andrew at $5 per kilogram in two weeks’

time.

With this contract in hand,

Andrew protects himself against the potential risk that wheat prices may

fall, knowing he will be able to sell his wheat at the guaranteed price of

$5 per kilogram in two weeks. Similarly, Ian hedges against the risk that

wheat prices may increase.

This ‘forward’ contract

between Andrew and Ian is an example of using derivatives as a hedge or risk

management tool. The contract has made Andrew’s and Ian’s cash flows more

predictable because Andrew knows he will receive $500 for 100 kilograms of

wheat from Ian in 2 weeks’ time, and Ian knows he will receive 100 kilograms

of wheat for $500, no matter how much the market price for wheat changes in

the meantime.

The value of the contract derives

from the performance of wheat prices, hence the name derivative. If the

market price for wheat unexpectedly increases to $8 per kilogram, then the

derivative contract is more valuable to Ian because he will still be able to

buy wheat at a bargain price of $5 per kilogram from Andrew, as stipulated

by the contract. Conversely, if the price unexpectedly decreases, the

contract is more valuable to Andrew, because he will be able to sell the

wheat at an above-market price.

|

Using derivatives to speculate

Investors who are prepared to accept additional risk often

use derivatives as a speculative tool. The purpose of speculation is to make a

profit from betting that the prices of assets will move in a favourable

direction. Complex derivatives allow investors to speculate on virtually

anything.

Hypothetical example of

using derivatives to speculate on price movement

Currently milk is priced at

$5 per litre, and Leah speculates that milk prices will go up in the near

future. Leah decides to spend $500 to buy a ‘futures’ derivative contract

from a derivatives exchange market.

The contract says Leah will

be entitled to receive 100 litres of milk from a third party in three

months’ time. The derivative exchange is the ‘middleman’ for brokering and

clearing this contract between Leah and the milk seller.

If the price of milk

increases, Leah’s contract for 100 litres will be worth more on the market

than the $500 she invested, and she can sell it at a profit. If the price

decreases, her contract will be worth less than $500, and she will lose

money when she sells it.

Two weeks pass and the market

price for milk has increased to $8 per litre.[8]

Leah decides to sell the contract to someone else (via the exchange) for

$800. Someone is willing to buy Leah’s contract for $800 because that is the

current market value of the underlying asset (ie milk) – provided the buyer

has no reason to expect the price of milk to fall again before the three

month term expires.

Leah has made a $300 profit,

not including fees and brokerage. In this case, rather than using

derivatives to reduce risk, Leah has taken on more financial risk for the

chance to speculate on the price movement of an asset. Leah never intended

to take delivery of 100 litres of milk.

|

What role do derivatives play in the financial markets?

Derivatives serve an important ‘price discovery’ role in the

economy as they can be used for establishing the prices of goods and services.

When used as a hedge, derivatives provide investors with predictable cash flows

and limit their risk exposure. Trading derivatives as a speculative tool can

also provide liquidity and price signals in the financial markets.

Derivatives trading has opened up a wide array of financial

markets for investors. For example, an Australian investor can speculate on the

price of American soybeans or the value of the Canadian dollar by using

derivatives.

On the other hand, mispriced and unregulated derivatives can

pose a risk to the global financial system, as

happened in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

How did mispriced derivatives contribute to the Global

Financial Crisis?

The rise of collateralised debt obligations

Professor

Michael Greenberger of the University of Maryland, among many others,

believes that the extensive misuse of derivatives

amplified the 2008 Global Financial Crisis – in particular, through the use of

a type of derivative known as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs).[9]

Explainer: what is a

collateralised debt obligation?

CDOs are a type of derivative

typically backed by a portfolio of loans (eg mortgages, bonds, credit cards

debts and student loans). They are typically sold by banks to investors to

free up more capital for the banks.

Buyers of CDOs would pay a lump

sum of money to the banks. In return, the buyers would receive a steady

stream of income, based on the payments made on the various loans that were

packaged into the CDOs.

In other words, the value of

CDOs derives from contracted loan and interest repayments by mortgage

holders, credit card holders and other debtors. If these debtors defaulted

on their loans (ie stopped making payments), the value of CDOs would fall

and buyers of CDOs could suffer financial losses.

As noted above, derivatives are

primarily used either to hedge or to speculate; CDOs can serve either of

these purposes. Buyers of CDOs speculate that debtors will not default and

that the CDO buyers will therefore continue to receive steady income from their

investment. Sellers of CDOs (eg banks) hedge against loan default risk and

protect their downside, because they are essentially transferring the loan

default risk to the CDO buyers.

|

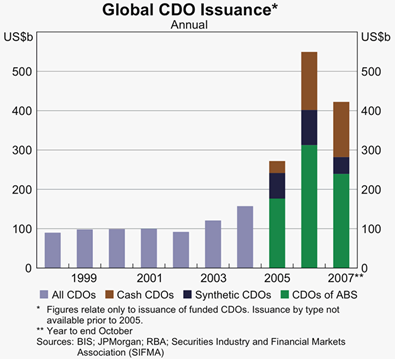

CDOs

grew in popularity in the United States in the early 2000s, with CDO

sales increasing from US$30 billion in 2003 to US$225 billion in 2006.[10]

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, global CDO issuance increased

sixfold from 2002 to 2006 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Issuance of CDOs increased significantly in the early 2000s

Source:

Susan Black and Alan Rai, ‘Recent Developments in Collateralised Debt Obligations

in Australia’, Reserve Bank of

Australia Bulletin (November 2007): 5.

Fuelled by a housing market boom

and an increase in mortgage uptake in the United States in the early 2000s,

banks made handsome profits by packaging various types of loans into CDOs and

selling them to investors.[11]

This was usually done via a subsidiary company called a special purpose vehicle

to shield the parental company from financial risk.[12]

There is a broad academic

consensus that CDOs were frequently overvalued prior to 2008.[13]

Additionally, the extent of banks’ exposure was opaque due to the complexity of

these derivatives, so the extent of systemic risk went unnoticed.[14]

Banks held CDOs on their ‘books’ before selling them to other investors (for

example, pension funds). Banks also invested in each other’s CDOs. As such, the

banking sector as a whole was financially exposed to a collapse in CDO value.

These problems were compounded by

credit rating agencies’ underestimation of CDOs’ real risk.

Misconduct of credit rating agencies

Many academics, such as Professor Lawrence White of the New

York University, argued that the misconduct of credit rating agencies contributed to the overvaluation of CDOs.[15]

Credit rating agencies are typically private companies paid

by banks or investors to assess the risk levels of

financial products. This includes determining the value and risk levels

of derivatives – for example, in the 2000s, whether CDOs were backed by

high-grade or subprime/riskier loans. However, for fear of losing their

customers (including banks that wanted to sell CDOs), credit rating agencies

often gave good credit ratings to CDOs backed by subprime/riskier loans.[16]

For example, some of the loans that were packaged into CDOs

were known as NINJA (no income, no job, no assets) loans that carried a high

risk of default.

These inflated credit ratings

meant that many CDOs were overvalued. Buyers of CDOs were unaware of the

default risk that these derivatives carried and assumed they were a good

investment. Put simply, CDOs were no longer an effective risk management tool

(which is the main purpose of derivative contracts) because investors were

unaware of the real risk CDOs carried.

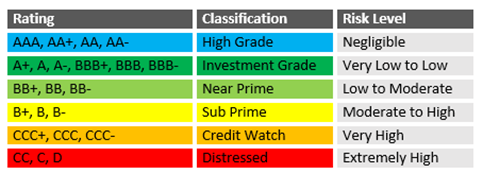

The table below shows examples of credit ratings and their

corresponding risk levels.

Table 1: examples of credit ratings and their supposed risk level

Source:

‘Equifax Credit Ratings’, Equifax Australasia

Credit Ratings Pty Ltd.

Potential consequences of incorrect

CDO credit ratings

Greg and Liz want to invest

their money. They each pay a lump sum of money to a bank to purchase some

CDO contracts.

The bank has packaged a

portfolio of its mortgage loans into mortgage bonds, and then repackaged the

mortgage bonds into CDOs. The CDOs are divided into different tranches with

different credit ratings, to cater to investors with different risk

appetites.

The bank’s CDO contracts

stipulate that buyers will receive a steady income stream as long as mortgage

holders meet the principal and interest repayments on their loans. If all

the mortgage holders default on their loans, the buyers of CDOs will stop

receiving this income stream.

Greg is a cautious investor

and only buys assets he considered to be safe. The CDOs Greg buys are all

AAA rated (the highest possible credit rating). This means that credit

rating agencies think the CDOs are backed by high-grade loans with very

little default risk. Greg is unaware that the AAA-rated CDOs he is

purchasing are in fact backed by subprime/riskier mortgage loans, because

the credit rating agencies’ risk assessment is incorrect.

Liz wants a higher return on

her investment. The CDOs Liz buys are BBB rated. She knows they are riskier

but offer higher returns.

Six months pass, and all the

mortgage holders default on their loans. Both Greg and Liz have stopped

receiving an income stream from their CDOs and have lost their initial

investments.

|

Regulation of derivatives trading prior to 2008

Despite sales of CDOs increasing exponentially in the early

2000s, CDO trading remained largely unregulated in the United States.

CDOs had traditionally been privately negotiated and traded

between 2 parties without going through a centralised

clearing exchange. Such privately negotiated derivatives are known as ‘over-the-counter’

(OTC) derivatives.[17]

Many officials in the United States Government at the time believed that

because OTC derivatives were mostly negotiated between sophisticated investors

who knew what they were getting into, derivatives trading needed less

regulation compared to other financial products.[18]

In 1998, the former Federal Reserve Chairperson Alan

Greenspan told Congress that ‘regulation of derivatives transactions that are

privately negotiated by professionals is unnecessary’.[19]

In 2000, Congress passed the Commodity

Futures Modernization Act that excluded derivatives trading from regulatory

oversight.[20]

Had CDO trading been conducted through centralised clearing

exchanges, United States regulators may have had an easier time overseeing the

derivatives market and stopping questionable trading practices.[21]

Instead, the private, bilateral nature of OTC derivatives meant there was a

lack of transparency concerning the risk profile of market participants in the

derivatives markets.[22]

Building a ‘house of cards’

In 2005 Professor Raghuram Rajan, the former Chief Economist

at the International Monetary Fund, warned that perverse incentives (coupled

with the wrong monetary policy) could lead banks and investment firms to take

excessive risks.[23]

There were strong incentives for investment managers at

banks and investment firms to generate profits because their pay or bonuses

were largely performance based. As such, Professor Rajan was concerned that

managers were incentivised to use innovative financial instruments, like

derivatives, to take excessive risks with company money in the hope of

generating high returns, which could then lead to a ‘catastrophic meltdown’ of

the financial system.[24]

Professor Nouriel Roubini of New York University described

the perverse incentive culture of investment managers:

People were essentially being rewarded for taking massive

risks. In good times, they generate short-term revenues and profits and

therefore bonuses. But that’s going to lead to the firm to be bankrupt over

time. That’s a totally distorted system of compensation.[25]

In the early 2000s, major banks traded an increasing number

of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) and derivative contracts that repackaged

MBSs. This increased their short-term profits but also significantly increased

their risk exposure, partially because they had incorrectly assessed the risk

levels of the derivatives.[26]

Put simply, derivatives were one of the financial tools

that allowed investment managers to take on excessive financial risks (for the

purpose of generating short-term revenues) without tipping off the regulatory

authorities.

In addition to CDOs, banks and investors used other complex

derivatives such as synthetic CDOs and credit default swaps (CDSs) to make ‘side

bets’ speculating on whether the value of CDOs would rise or fall.[27]

Explainer: what is a

credit default swap (CDS)?

CDSs are a type of derivative

contract that functions like an insurance policy.

Suppose Jonathan has lent a

large sum of money to a borrower. Jonathan purchases a CDS on the loan by

making a series of cash ‘insurance premium’ payments to an insurance

company. In return, the insurance company promises to compensate Jonathan if

the borrower defaults on the loan.

The key difference between a

real insurance policy and a CDS is that a CDS can also be used by

speculators to insure against a borrower default on somebody else’s

loan.

Suppose Melanie, who is not

involved in Jonathan’s loan at all, decides to purchase a CDS on Jonathan’s

loan. If the borrower defaults on Jonathan’s loan, Melanie also gets paid by

the insurance company. In other words, Melanie has made a ‘side bet’

speculating that the borrower will default on Jonathan’s loan.

Journalist Matthew O’Brien

from The Atlantic has compared CDSs to buying a car insurance policy

on somebody else’s car in which you only get paid if that person gets into a

car crash.[28]

The underlying message here is that CDSs create perverse incentives.

For example, because Melanie

has purchased a CDS on Jonathan’s loan, Melanie presumably hopes that

Jonathan’s loan goes bad, so she can get paid by the insurance company.

Melanie may even take actions to ensure that the borrower defaults on

Jonathan’s loan.

Pope Francis said:

The spread of such a kind of

contract without proper limits has encouraged the growth of a finance of

chance, and of gambling on the failure of others, which is unacceptable from

the ethical point of view.[29]

|

Banks and investors used CDSs to

hedge against the potential risk of loan default. While this decreased the risk

exposure of investors, it significantly increased the risk exposure of major

insurance companies.

American International Group (AIG),

one of the world’s largest insurance companies, was a prolific underwriter and

seller of CDSs. Many investors purchased AIG’s CDSs because they had lent out

money and wanted to be compensated if the loans went bad. Many speculators, who

were not themselves parties to the loans, also purchased CDSs to speculate that

the loans would go bad.

As OTC derivative markets were largely unregulated, in

theory AIG could underwrite and sell unlimited CDSs even if it did not have

enough collateral to pay out the CDSs when loans went bad.

In 2008, the New York Times featured an

article that reported AIG’s Financial Products Division had underwritten

and sold CDSs worth $500 billion (US dollars), and that the company was receiving

as much as $250 million a year in income from CDS ‘insurance premiums’.[30]

Many of these CDSs were to provide insurance to financial institutions holding

CDOs, in case loan borrowers defaulted.

In other words, the investment managers at AIG took

excessive risks and miscalculated the chance of a mass loan default, and

therefore grossly mispriced the CDSs they had underwritten.[31]

It is unclear whether the senior executives of the AIG knew

the company had sold CDSs in excess of its ability to pay out in the event of a

mass loan default. Nevertheless, the investment managers’ focus on short-term

gains and a lack of regulatory oversight meant that very few people at AIG had

the incentives to speak out against excessive risk-taking.

Through holding a large volume of mispriced derivatives

on their balance sheets, major banks and insurance companies became extremely

exposed to the potential risk of a mass default on subprime mortgages and other

related loans.

Professor

Frank Partnoy of the University of California explained how derivatives

amplified risk exposure, spreading it throughout financial markets:

If you were a homeowner with a risky subprime mortgage loan,

CDO arrangers might put together a hundred side bets on whether you would

default. Through credit default swaps, a hundred investors around the world

could be exposed to the risk that you might not make your next monthly

payments.[32]

The collapse of a ‘house of cards’

It is worth repeating that a derivative contract derives

its value from an underlying asset, with the asset underlying a CDO in the

cases above being an income stream from subprime mortgage repayments. If this

asset becomes worthless – for example because the borrower defaults on the loan

– then the derivative CDO also becomes worthless.

When the American housing market slowed down in 2007–08

after a two-decade housing boom, many mortgage holders started to default on

their loans, and the number of home foreclosures increased substantially.[33]

It became increasingly evident that the value of CDOs reliant on subprime

mortgage repayments had been vastly overstated.

While some banks did not know the exact extent of the losses

they faced from holding these overvalued CDOs, other banks actually attempted

to sell overvalued CDOs to unsuspecting investors to mitigate their losses.[34]

The resulting fear and uncertainty made banks and investors reluctant to lend

money, contributing to a global ‘liquidity

crunch’ that exacerbated the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.[35]

To ‘bail out’ AIG and some major banks, the United States

Government implemented the Troubled Asset Relief Program to purchase up to $700

billion in distressed assets from these companies to keep them solvent.[36]

In 2009, President Barack Obama said:

Under these circumstances, it's hard to understand how

derivative traders at AIG warranted any bonuses, much less $165 million in extra

pay. How do they justify this outrage to the taxpayers who are keeping the

company afloat?[37]

Regulation of

derivatives trading in Australia

Why is regulation of derivatives trading so challenging?

Regulation of derivatives trading is challenging because

governments may not always have adequate information on the derivatives market.

Economist Vania Stavrakeva argues:

Derivatives are much more complicated contracts than regular

loans, bond and equity purchases and have very different accounting standards.

In order to estimate the exposure of banks to systemic crises caused by

derivative positions, regulators will need both bank specific transaction level

data and fairly complex value at risk models …

Of course one should not forget that derivatives can also

improve welfare by allowing firms and financial institutions to hedge risk and

by improving risk sharing. Therefore, one needs to be careful not to

overregulate.[38]

Implementation of G20 reforms

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis prompted a comprehensive international

regulatory response, directed through the G20 forum (including Australia).[39]

G20 leaders agreed in September 2009:

All standardised OTC derivative contracts should be traded on

exchanges or electronic trading platforms, where appropriate, and cleared

through central counterparties by the end of 2012 at the latest. OTC derivative

contracts should be reported to trade repositories. Non-centrally cleared

contracts should be subject to higher capital requirements.[40]

As noted, the lack of data on derivatives trading has made

it more difficult for regulatory agencies to adequately supervise the

derivatives market. Before the 2008 global financial crisis, regulators in

Australia generally only had access to highly aggregated data to understand the

OTC derivatives market, and the 2008 crisis highlighted that these aggregated

data are ‘insufficient to shed light on the vulnerabilities that can exist when

there is a web of derivative transactions between a large variety of firms’.[41]

Consequently, the Australian Government has introduced a

suite of legislative

changes designed to improve transparency and reduce systemic risk

associated with derivatives trading. The legislative changes also align with

Australia’s commitment to implement the Basel III

agreement that prescribes banks’ capital and liquidity requirements for

derivatives transactions.

For examples, the Corporations

(Derivatives) Determination 2013 empowers the Australian Securities and

Investments Commission (ASIC) to make rules imposing reporting requirements on

a range of derivatives.[42]

The ASIC

Derivative Transaction Rules (Reporting) 2013 set out the rules for reporting

derivative transactions to trade repositories. The ASIC

Derivative Transaction Rules (Clearing) 2015 impose a mandatory central

clearing regime for OTC interest rate derivatives denominated in major currencies.

These reforms have greatly increased the information

that regulators have about the Australian derivatives market.[43]

On the other hand, some stakeholders warn the risks of

overregulation, especially considering that the COVID-19 pandemic placed

significant operational burden for market participants. For example, the

brokerage firm Pepperstone has said:

… we are concerned that some of the requirements in CP

322 are overly stringent, and do not allow for investors who understand and

accept the risks associated with trading our products to trade the way they

require. We are concerned that this restriction on investors’ freedom of choice

will result in them seeking alternatives outside of Australia, even if it means

trading outside of a regulated jurisdiction. [44]

Multilateral cooperation

Although Australian regulators have been implementing G20

reforms to reduce systemic risks in the financial sector, as an open economy

Australia remains exposed to risks in the world economy. As such, Australia has

an interest in promoting multilateral efforts to strengthen the international

institutions and mechanisms needed to manage these risks.

Australia is a member of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body that monitors the

stability of the global financial system and publishes an annual

progress report on the implementation of OTC derivatives reforms. Since

2009 Australian regulators have worked with other members of the FSB to resolve

cross-border issues that have arisen in the implementation of OTC derivatives

reforms.[45]

Derivatives trading in the 2020s

Bespoke CDOs

Today, derivatives trading is widespread and accessible. An

increasing number of equity and even cryptocurrency exchanges are offering a

wider range of derivatives.[46]

According to a report

by the World Federation of Exchanges, more than 32 billion derivative

contracts were traded in 2019.[47]

Trading volumes in CDOs decreased significantly after 2008.[48]

However, more recently, banks have once again been increasing their CDO sales.

Due to CDOs’ negative connotations, banks have renamed these derivatives ‘bespoke tranche

opportunities’ or ‘bespoke CDOs’.[49]

These new bespoke CDOs are predominantly purchased by hedge funds and other

institutional investors seeking higher returns.

In April 2019, Reuters reported that:

Trading volumes in synthetic

collateralised debt obligations linked to credit indexes are up 40% this year,

according to JP Morgan, after topping US$200bn in 2018 on the back of three

years of double-digit growth. Meanwhile, analysts predict more than US$100bn in

sales of bespoke synthetic CDOs in 2019 following an estimated US$80bn of

issuance last year.[50]

Banks have argued that the new bespoke CDOs are now backed

by safer loans rather than subprime mortgages.

Total return swaps

In March 2021, Bill Hwang, the founder of Archegos Capital

Management, used a type of OTC derivative known as a total return swap (TRS) to

indirectly invest in the US stock market. The TRS contracts significantly

increased Archegos Capital’s risk exposure, because TRSs are designed to allow

investors to trade on margin by using borrowed money (illustrated in the

example below).[51]

Archegos Capital lost an estimated US$20 billion in 2 days and caused its

lenders to lose tens of billions.[52]

Hypothetical example of

using total return swaps (TRSs) to speculate

Shannon wants to buy 100

shares of a company’s stock, but only has enough money for 20 shares.

Shannon also does not want her friends to know she invests in the stock

market.

Shannon decides to enter into

a TRS contract with a bank. The TRS contract stipulates that the bank will

purchase 100 shares of the company’s stock. If the share price increases,

then Shannon will receive the profit (minus bank fees and brokerage).

This means the bank has

essentially purchased 100 shares of the company’s stock on behalf of

Shannon. Note that Shannon does not technically own the shares; the bank

does. This gives Shannon the anonymity she desires while also allowing her

to profit from a rise in the share price.

The bank is willing to enter

into the TRS contract with Shannon because she has put up her money (which

is enough to buy only 20 shares) as collateral. If the share price falls by

20% and wiped out Shannon’s initial investment, the bank will ask Shannon to

put up more collateral (known as a margin call).

If Shannon cannot afford to

put up more collateral, the bank will liquidate her position by seizing the

collateral and forcibly selling the shares at a 20% loss. This means Shannon

will lose her initial investment and 100 shares. In theory, the bank should

not suffer any loss, because it would have sold 100 shares and seized

Shannon’s initial investment/collateral (which was enough to purchase only

20 shares) to make up the 20% fall in the share price.[53]

Fortunately for Shannon,

after she enters into the TRS contract with the bank, the share price

increases by 20%. Shannon tells the bank to sell the shares and concludes

her TRS contract.

Because Shannon has been

trading on a leveraged position by using the TRS, this means that although

the share price increased only by 20%, Shannon has doubled her initial

investment, excluding bank fees and brokerage. In conclusion, margin trading

by using TRS amplifies the potential gains and losses for investors.

|

Because Archegos Capital was a

relatively low-profile family office, it was not subject to the same regulatory

scrutiny as major hedge funds. This allowed Archegos Capital to enter into TRS

contracts with 6 major investment banks simultaneously without disclosing to

any single bank or the regulatory authority that it had multiple TRS contracts

with other banks.[54]

One commentator described Archegos Capital’s decisions as:

Imagine you go to four mates separately, borrow £1000 from

each without telling the other, and go to a casino and put it [sic] all that

money on red.[55]

In other words, the TRS allowed Archegos Capital to trade on

margin and take a highly leveraged position on selected stocks. When the stock

price fell and Archegos Capital could no longer afford to put up the collateral

to maintain its leveraged position, it caused a stock fire sale that further

depressed the stock price. This wiped billions of dollars off the stock market

and resulted in ‘one of the single greatest losses of personal wealth in

history’.[56]

The Financial Times featured an article that

commented on the potential destructive power of derivatives:

The Archegos Capital debacle has exposed the hidden risks

of the lucrative but opaque equity derivatives business through which banks

empower hedge funds to make outsize [sic] bets on stocks and related assets.

The soured wagers made by Bill Hwang’s family office have

triggered significant losses at Credit Suisse and Nomura, underscoring how

these tools can cause a chain reaction that cascades across financial markets.[57]

[emphasis added]

The collapse of Archegos Capital has prompted financial

regulators around the world to investigate their risk control measures.[58]

For example, the Financial Times reported that Hong Kong’s central bank

and financial regulator are planning to use centralised trade databases to

identify excessive risk-taking by banks and investment funds trading

derivatives on Hong Kong markets.[59]

Conclusion

Derivatives are powerful financial tools that can help

investors to manage risk and limit investment exposure. However, derivatives

can also lead to excessive speculative trading and significantly increase

investors’ risk exposure.

On a large enough scale, mispriced derivatives can endanger

the entire financial system. Like any other powerful tool, derivatives need to

be properly monitored and regulated. Consequently, it is important that

Australian regulatory agencies are effective in carrying out their supervision

of derivatives trading, complemented by continued promotion of multilateral cooperation

to implement derivatives market reforms.

[1]. Carl Schwartz,

‘G20

Financial Regulatory Reforms and Australia’, Reserve Bank of Australia

Bulletin, September quarter 2013.

[2]. The Australian

Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Prudential

Regulation Authority (APRA) are the two most prominent regulators of the

Australian financial services industry. This is commonly referred to as the ‘Twin

Peaks’ model of financial regulation. In addition to the twin regulators (ASIC and

APRA), other agencies such as the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Treasury, and

the Council of Financial Regulators also play a role in the regulation of

Australia’s financial services industry.

[3]. Daniel Tischer,

Adam Leaver and Jonathan Beaverstock, ‘Collateralised

loan obligations: why these obscure products could cause the next global

financial crisis’, The Conversation, 22 September 2021.

[4]. Vania Stavrakeva,

‘Derivative

regulation: Why does it matter?’, Think at London Business School, 1

September 2013.

[5]. Mayra

Valladares, ‘Leveraged

loans and collateralized loan obligations are riskier than many want to admit’,

Forbes (online), 22 September 2019.

[6]. ‘About

derivatives statistics’, Bank for International Settlements.

[7]. ‘Exposure’ in finance

means the amount of money an investor stands to lose if the investment fails.

[8]. Typically a

person can choose to sell a futures contract at any time before the contract

expiry or ‘delivery’ date.

[9]. Michael

Greenberger, ‘The

Role of Derivatives in the Financial Crisis’, Testimony of Michael

Greenberger before Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission Hearing, 30 June

2010, 1.

[10]. Sergey Chernenko,

Samuel Hanson and Adi Sunderam, ‘The

Rise and Fall of Demand for Securitizations’, National Bureau of

Economic Research Working

Paper 20777, (December 2014), 1. United

States Government, ‘The

Financial Crisis Inquiry Report’, Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission,

130.

[11]. Adrian

Blundell-Wignall, ‘Structured

Products: Implications for Financial Markets’, OECD Journal Financial

Market Trends 2, (2 November 2007): 27–57, 33.

[12]. Janet Tavakoli,

‘Structured

Finance: Uses (and Abuses) of Special Purpose Entities’.

Presentation to the Federal Reserve Conference on Bank Structure and

Supervision, Chicago, May 2003.

[13]. Robert Jarrow, ‘The Role of ABS, CDS and CDOs in the Credit Crisis and

the Economy’, in Alan Blinder, Andrew Loh and Robert

Solow, eds, Rethinking the Financial Crisis, (New York: Russell Sage

Foundation, 2012), 210–234.

[14]. Sirio Aramonte

and Fernando Avalos, ‘Structured

finance then and now: a comparison of CDOs and CLOs’, Bank for

International Settlements Quarterly Review, (22 September 2019), 13. See

the definition of ‘exposure’ in note 6.

[15]. Lawrence White, ‘The credit-rating agencies and the subprime debacle’, Critical Review: A Journal

of Politics and Society 21, no. 2 (13 July 2009): 389–399.

[16]. Mark Rom, ‘The

Credit Rating Agencies and the Subprime Mess: Greedy, Ignorant, and Stressed?’

Public Administration Review 69, no. 4 (6 July 2009): 640–650, 641.

[17]. Over-the-counter

derivatives .usually have a higher credit risk, where one or both parties to

the contract may potentially default on the terms of the agreement.

[18]. US Department

of Treasury, ‘Over-the-Counter

Derivatives Markets and the Commodity Exchange Act’, Report of the

President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (November 1999): 15.

[19]. Federal Reserve

Board, ‘The

regulation of OTC derivatives’, testimony of

Chairman Alan Greenspan before the Committee on Banking and Financial Services,

U.S. House of Representatives, 24 July 1998.

[20]. Lynn Stout, ‘How Deregulating

Derivatives Led to Disaster, and Why Re Regulating Them Can Prevent Another’,

Cornell Law Faculty Publications Paper 723, no. 1 (July 2009): 7.

[21]. Ron Hera, ‘Forget

about housing, the real cause of the crisis was OTC derivatives’, Business

Insider Australia, 12 May 2010.

[22]. Bernard Pulle,

‘Over-the-counter

derivatives—high risk investments in a largely unregulated market’, Parliamentary

Library Briefing Book: Key Issues for the 44th Parliament, (Canberra: Parliamentary

Library, 2013), 42–43.

[23]. Raghuram Rajan,

‘Has

financial development made the world riskier?’, Proceedings - Economic

Policy Symposium - Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,

(August 2005): 313–369, 315.

[24]. Rajan, 318.

[25]. Nouriel

Roubini, ‘Insider Job’, transcript,

Sony Pictures Classics, October 2010.

[26]. Susan Wachter,

Adam Levitin and Andrey Pavlov, ‘Bad

and Good Securitization’, Wharton Real Estate Review 13, no. 23

(2009): 23–34, 33.s

[27]. John Authers, ‘Why

bets on synthetic CDOs must be banned’, Financial Times, 24 April

2010.

[28]. Matthew

O’Brien, ‘How

to Make Money for Nothing Like Wall Street’, The Atlantic, 25

October 2013.

[29]. Joe Rennison, ‘Pope

says credit default swaps are unethical’, Financial Times, 18 May

2018. The original bulletin released by the Holy See Press Office is provided

here.

[30]. Gretchen

Morgenson, ‘Small

unit in London pushed AIG into the skid that nearly destroyed it’, New

York Times, 28 September 2008.

[31]. If AIG had

correctly calculated the chance of a mass loan default, presumably it would

have charged higher insurance premiums for the CDSs it issued. As an analogy,

if an insurance company knows a customer is a bad driver, it charges them a

higher premium for car insurance.

[32]. Frank Partnoy,

‘Frank

Partnoy: Derivative Dangers’, NPR Fresh Air program, transcript,

National Public Radio, 25 March 2009.

[33]. Susan Wachter

and Benjamin Keys, ‘The

Real Causes — and Casualties — of the Housing Crisis’, Knowledge at

Wharton podcast, transcript, 13 September 2018.

[34]. Jonathan Stempel,

‘Goldman

loses bid to end lawsuit over risky CDO’, Reuters, 22 March 2012.

[35]. Thomas Hogan, ‘What

Caused the Post-crisis Decline in Bank Lending?’, Rice University’s

Baker Institute for Public Policy: Issue Brief 01.10.19, 1.

[36]. ‘Troubled

Assets Relief Program (TARP)’, U.S. Department of Treasury.

[37]. Jeff Mason and

David Alexander, ‘Outraged

Obama goes after AIG bonus payments’, Reuters, 17 March 2009.

[38]. Vania Stavrakeva,

‘Derivative

regulation: Why does it matter?’, Think at London Business School, 1

September 2013.

[39]. Carl Schwartz,

‘G20

Financial Regulatory Reforms and Australia’, Reserve Bank of Australia

Bulletin, September quarter 2013.

[40]. G20 Information

Centre, G20

Leaders Statement: The Pittsburgh Summit, 24–25 September 2009.

[41]. Duke Cole and Daniel

Ji, ‘The

Australian OTC Derivatives Market: Insights from New Trade Repository Data’,

Reserve Bank of Australian Bulletin, 21 June 2018.

[42]. Australian

Securities and Investments Commission, ‘Regulatory

Guide 251: Derivative transaction reporting’, 5.

[43]. Duke Cole and

Daniel Ji, ‘The

Australian OTC Derivatives Market: Insights from New Trade Repository Data’,

Reserve Bank of Australian Bulletin, 21 June 2018.

[44]. Pepperstone, submission

to ‘ASIC

Consultation Paper 322 Product Intervention: OTC binary options and CFDs’,

1.

[45]. Carl Schwartz,

‘G20

Financial Regulatory Reforms and Australia’, Reserve Bank of Australia

Bulletin, September quarter 2013.

[46]. Justina Lee, ‘How

Derivatives Amp Up Already Heady Crypto Markets’, Bloomberg News, 17

July 2021.

[47]. World

Federation of Exchanges, ‘The

WFE’s Derivatives Report 2019’, 26 June 2020, 3.

[48]. Paul Davies and

Stacy-Marie Ishmael, ‘CDO

issuance ‘to drop 60%’ in 2008’, Reuters, 8 January 2008.

[49]. ‘Bespoke’ also refers

to the fact the buyers can now customise the CDOs to fit their specific risk

appetite. The appeal of bespoke CDOs is that they typically offer investors

higher returns than can be found in the global bond markets.

[50]. Christopher

Whittall, ‘Banks,

investors pile back into synthetic CDOs’, Reuters, 30 April 2019.

[51]. Margin trading

refers to the practice of using borrowed money to buy and sell a financial

asset.

[52]. Leo Lewis,

Tabby Kinder and Owen Walker, ‘Credit

Suisse and Nomura warn of losses after Archegos-linked sell-off’, Financial

Times, 30 March 2021.

[53]. The reality may

be more complicated, a bank could suffer losses if it tries to sell too many

shares too fast which will further drive down share prices.

[54]. Matt Scuffham,

John Revill and Makiko Yamazaki, ‘Global

banks brace for losses from Archegos fallout’, Reuters, 29 March

2021.

[55]. Kieran King, ‘The Archegos Saga and Total

Return Swaps Explained’, YouTube, 8 April 2021.

[56]. Katherine

Burton and Tom Maloney, ‘One

of world’s greatest hidden fortunes is wiped out in days’, Sydney

Morning Herald, 1 April 2021.

[57]. Robert

Armstrong, ‘Archegos

debacle reveals hidden risk of banks’ lucrative swaps business’, Financial

Times, 1 April 2021.

[58]. Tabby Kinder, ‘Hong

Kong plans new risk controls to prevent Archegos-style collapse’, Financial

Times, 31 August 2021.

[59]. Kinder, Financial

Times.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Entry Point for referral.