20

January 2023

PDF version [1.2MB]

Geoff Gilfillan

Statistics and Mapping

Executive

summary

In the context of Australia’s debate over

energy policy, comparisons are sometimes made between the number of jobs

provided in the coal mining industry compared to the renewable energy sector.

Comparisons of employment between the two industries are problematic given the

significant differences in activities undertaken and their respective use of

labour and capital.

Different data sources provide a range of

estimates for coal mining employment in Australia. Some sources show falls in

employment in the sector in the past 5 to 10 years while others show an

increase.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

has also provided estimates for employment in renewable energy activities from

2009–10 to 2018–19. ABS Census of Population and Housing (Census)

data also sheds light on employment associated with electricity generation from

renewable and non-renewable sources (including coal) in 2016 and 2021.

Coal mining

employment

- The ABS Labour Account data series shows 34,300 people

were employed in the coal mining industry across Australia in 2021–22. This is

12,200 or 26.2% less than the peak of 46,400 achieved in the sector (using this

series) in 2013–14. There were 36,000 jobs in the coal industry in 2021–22

which accounted for 0.2% of the 14.9 million jobs recorded in all industries.

- The ABS Australian Industry data series shows 37,335

people employed in the coal mining industry at the end of June 2021, which

compares with a peak of 45,016 at the end of June 2012. This constitutes a fall

of 7,681 or 17.1%.

- ABS Labour Force survey (LFS) data shows 44,600 people

were employed in coal mining across Australia in November 2022 (based on 4

quarter moving averages of original data).[1]

This is 11,200 or 20.1% less than the peak of 55,800 achieved in May 2014.

- LFS data shows 26,800 people were employed in the coal industry

in Queensland (using the same methodology) in November 2022 and 14,300 were

employed in New South Wales (NSW). Coal mining employment has fallen in both

states between May 2014 and November 2022, with the fall being much more

pronounced in NSW. Coal mining employment fell by 12,400 or 46.4% in NSW and by

900 or 3.3% in Queensland.

- ABS Census showed 49,616 people employed in coal mining in

Australia in 2021. This is an increase of 3,121 or 6.7% from 2016 when 46,495

people were recorded in the industry. Census data shows 26,029 people were

working in the coal industry in Queensland in 2021 and 20,770 were working in

NSW.

- The biggest regional concentrations of coal mining employment in

2021 (using Census data) were in Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday at 13,335 (up 3,380 or

34.0% from 2016), Hunter Valley at 10,056 (up 1,232 or 14.0%) and Central

Queensland at 7,349 (up 679 or 10.2%).

Summary of coal mining employment and jobs estimates

| Data source |

Time period |

New

South Wales |

Queensland |

Australia |

| Employment |

| ABS, Labour

Account |

2021–22 |

na |

na |

34,300 |

| ABS, Labour

Force, detailed |

November

2022 (4 quarter moving average) |

14,300 |

26,800 |

44,600 |

| ABS, Australian

Industry |

June 2021 |

na |

na |

37,335 |

| ABS, Census

of Population and Housing |

2021 2016 |

20,770 18,889 |

26,029 25,221 |

49,616 46,495 |

| Queensland

Government, Resources Safety and Health Queensland |

June 2022 |

na |

37,970 |

na |

| Coal

Services Australia |

June

2021, (production employment) |

21,979

FTE workers |

na |

na |

| Jobs |

| ABS, Labour

Account |

2021–22 |

na |

na |

36,000 |

| ABS, Jobs

in Australia |

2019–20 |

15,500 |

20,200 |

50,800 |

na = not available; FTE = full-time equivalent.

Note: Employment is the number of people working in coal

mining at a point-in-time. Jobs are those job placements in which the occupant

receives remuneration in wages, salary, payment in kind, or piece rates over a

financial year. This excludes self-employment jobs held by owner managers of unincorporated

enterprises.

- ABS Jobs in Australia data shows 50,800 jobs recorded in

coal mining during the 12 months of 2019-20. This is an increase of 7,400 or

17.0% compared with 2018–19. A substantial increase in coal mining jobs was

recorded in WA (up from 6,600 to 11,600). Jobs in Queensland increased by 1,900

or 10.5% while jobs in NSW fell by 1,000 or 6.1%.

- Mine

and quarry safety data released by the Queensland Government Department of

Resources, Safety and Health, shows 37,970 people were working in operational

coal mines in Queensland in June 2022. This data source shows in the 5 years to

June 2022 employment in the coal industry in Queensland grew by 7,018 or 22.7%.

- The Coal Services[2]

Annual Report of 2021 showed 21,979 full-time equivalent (FTE) workers in

coal mining production activities in NSW in June 2021. This source showed FTE employment

in coal mining production activities increased by 2,591 or 13.4% in NSW in the 5

years to June 2021.

Employment

in renewable energy activities and electricity generation using fossil fuels

After a period of decline between 2011–12

and 2015–16 employment in the renewable energy sector has risen rapidly since.

- Data collected by the ABS shows there were 26,850 FTE jobs in the

renewable energy sector in Australia in 2018–19, up by 15,370 or 133.9% since

2015–16. In the period between 2015–16 and 2018–19 growth in employment in

renewable energy activities was strongest in large scale solar (up more than

tenfold), followed by wind (which more than quadrupled), and installation of roof

top solar photo-voltaic (PV) (which more than doubled).

- ABS unpublished data shows 5,750 FTE jobs in ongoing operational

renewable energy generation activities in 2018–19 (as opposed to installation),

with hydro accounting for the most jobs (at 3,060).

ABS Census data shows Australia recorded a

substantial fall in employment in fossil fuel electricity generation across

Australia between 2016 and 2021 (down 1,435 or 17.8% to 6,630), and large

increases in employment in both hydroelectricity generation (up 606 or 54.5% to

1,718) and other (renewable) forms of electricity generation (up 1,002 or

115.7% to 1,868).

- Across Australia employment in renewable electricity generation

(hydro plus other) accounted for 34.3% of total employment in electricity

generation in 2021, which compares with a 19.2% share in 2016.

- Around 52.3% of employment in electricity generation using fossil

fuels is based in non-metropolitan areas. By comparison, 60.5% of employment in

electricity generation using renewables was based in capital cities.

Contents

Executive

summary

Coal mining employment

Summary of coal mining employment and

jobs estimates

Employment in renewable energy

activities and electricity generation using fossil fuels

Introduction

Coal mining industry

Coal mining contribution to the

national economy

National coal mining employment

estimates

ABS Labour Account

Figure 1 Number of people employed

in the coal mining industry, annualised data, 1994–95 to 2021–22

ABS Labour Force Survey

Figure 2 Employment in coal mining

in Australia—original estimates and average of preceding 4 quarters, 1984 to

2022

ABS Australian Industry

ABS Jobs in Australia

ABS Census of Population and Housing

Occupations in the coal industry

State and territory coal mining

employment estimates

ABS Labour Force Survey

Table 1 Employment in the coal

industry by major state/territory, 1985 to 2022

ABS Census

Table 2 Employment in the coal

industry by state and territory, 2016 and 2021

Jobs in Australia

Table 3 Coal mining jobs by state/territory,

2019–20

Other estimates for coal mining

employment in NSW and Queensland

Regional coal mining jobs and

employment estimates

ABS Jobs in Australia

Table 4 Ranking of coal mining

jobs by SA4 region, 2018–19 and 2019-20

ABS Census employment

Table 5 Major regions for coal

mining employment, 2016 and 2021

Renewable energy sector and fossil

fuel electricity generation

Renewable energy contribution to

total electricity generation

Figure 3 Renewable share of total

electricity generation in Australia, 1960–61 to 2020–21

Table 6 Australian electricity

generation, by fuel type; 2000–01, 2015–16 and 2020–21

Employment estimates for the

renewable energy sector

Figure 4 FTE employment in renewable

energy activities, 2009–10 to 2018–19

Table 7 FTE employment by

renewable energy type, selected years from 2009–10 to 2018–19

Table 8 FTE employment in

renewable energy activities by state and territory, selected years from 2009–10

to 2018–19

Ongoing operational employment in

renewable energy activities

Table 9 FTE ongoing operational

employment by energy type, selected years from 2009–10 to 2018–19

Employment in fossil fuel and

renewable electricity generation

Table 10 Number of people

employed in electricity generation by energy type by state and territory, 2021

Table 11 Percentage of share of

total people employed in electricity generation by type and state and

territory, 2016 and 2021

Other estimates for employment in

renewables and projections for future employment

Conclusion

Appendix

ABS Methodology for calculating

renewable energy employment

Introduction

In the context of Australia’s debate over

energy policy, comparisons are sometimes made between the number of jobs

provided in the coal mining industry compared to the renewable energy sector. However,

comparisons of employment between the two industries are problematic given the

significant differences in activities undertaken and their respective use of

labour and capital.

This statistical snapshot provides estimates for employment

in the coal industry and the renewable energy generation sector. The purpose of

the paper is to highlight the different employment estimates that are available

for each industry sector and to establish whether any trends exist over time.

Coal mining is highly capital intensive with fewer people

required to operate the large machinery used to extract coal deposits. The coal

industry is composed of thermal coal extraction which is used in electricity

generation and metallurgical coal extraction which is used in steel making.

Some thermal coal is used for local electricity generation, but a significant

proportion is exported, and much of the metallurgical coal that is extracted is

exported overseas. The employment estimates that are available do not

distinguish between thermal and metallurgical coal mining activities.

Employment in coal mining is restricted to regions in which

there are viable deposits of thermal and metallurgical coal whereas employment

in renewable energy has the potential to be far more widespread. For example,

coal mining employment is highly concentrated in regional parts of Queensland

and NSW, with smaller deposits found in Collie in Western Australia (WA).

Renewable energy production activities are quite varied, ranging

from larger scale solar, wind turbine and hydro electricity generation, to

smaller scale installation of photovoltaic panels and solar hot water systems

in private dwellings and businesses. Large scale renewable energy projects

require relatively few people to maintain and operate whereas smaller scale

rooftop solar installation is much more labour intensive.

As a result of these differences, caution is advised in making

direct comparisons between the two sectors. Nevertheless, it is interesting to

observe trends in employment in both these sectors as they have responded to

changing domestic and international demand for different sources of energy.

This first section of the paper examines the contribution of

the coal mining industry to the national economy and compares the various

estimates available for employment and jobs in the sector.

The second section of the paper examines the emergence of

the renewable energy sector and its growing contribution to total electricity

generation. This section includes employment estimates for both renewable and

non-renewable sources of electricity generation over time.

Coal mining industry

Coal mining

contribution to the national economy

Coal mining is a relatively small employer

in industry share terms but contributes significantly to the Australian economy

in terms of export revenue.

Australia produced 172 Mt (Million tonnes)

of metallurgical coal in 2021–22 of which 163 Mt was exported. Australia also

produced 246 Mt of thermal coal of which 196 Mt was exported. Exports of

metallurgical coal were worth $67.6 billion in 2021–22 while exports of thermal

coal were worth $46.3 billion.[3]

Total exports of coal were valued at $114

billion in 2021–22 which accounted for 19.1% of the value of total exports of

goods and services from Australia. This compares with an 8.5% share of total

exports of goods and services in 2020–21 when coal exports were valued at $39.2

billion.[4]

While production of coal increased slightly

in 2021–22 compared with the previous financial year, prices of coal increased

significantly in the months following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in

February 2022. [5]

The average export price for high quality metallurgical coal increased from

$145 per tonne in 2020–21 to $455 per tonne in 2021–22, while average export

price for thermal coal increased from $83 per tonne to $236 per tonne during

the same period.[6]

The coal mining industry accounted for 0.8%

of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Australia in 2021–22 (measured in chain

volume terms). By comparison iron ore mining accounted for 6.2% of GDP and the

whole mining sector (including exploration and support services) accounted for 10.3%.[7]

The ABS Australian Industry publication

showed coal mining received $51.8 billion in sales and service income in

2020–21 while industry valued added (IVA)[8]

in the sector amounted to just over $16 billion. The coal mining industry

accounted for 1.2% of total industry value added generated in selected

industries in the private sector in 2020–21.[9]

National coal mining

employment estimates

The ABS provides several estimates for employment in the

coal mining industry. Some ABS estimates are derived from survey data or the

Census, while others draw on businesses data. Additional employment estimates

are available from state government departments and an industry association

committed to ensuring worker safety in the industry. The differences in these

estimates are highlighted in the following section.

ABS Labour

Account

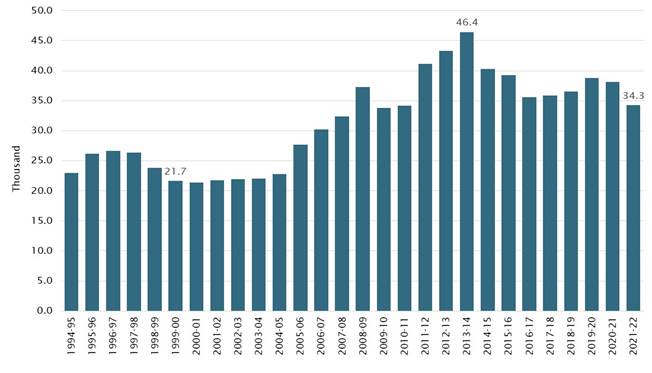

The ABS Labour

Account data series shows there were 34,300 people employed in the coal

mining industry across Australia in 2021–22 (see Figure 1).[10]

There were 36,000 jobs in the coal industry in 2021–22 which was equivalent to

0.2% of the 14.9 million jobs recorded in the economy. The level of employment

in the coal industry recorded in 2021–22 was 12,200 or 26.2% down on the peak

of 46,400 achieved in 2013–14, but much higher than the level recorded in 2000–01

(at 21,400).

The coal mining industry share of total jobs

in the economy has ranged from 0.2% to 0.4% between 1994–95 and 2021–22, with

the share being as high as 0.4% between 2011–12 and 2013–14. By comparison, the

whole mining industry accounted for 1.4% of total jobs in all industries in

2021–22, while industries such as Retail trade contributed 9.9%, Construction

contributed 8.5% and Health care and social assistance contributed 13.5%.[11]

The advantage of the Labour Account data

series is its use of a combination of household, business and administrative

data rather than just household survey data used for the Labour Force Survey

(LFS).[12]

Enterprises are allocated an industry classification [13]

according to the type of activities in which they are directly engaged.

The employment estimates by industry provided

in the Labour Account also include people whose main job may be in another

industry (i.e. they include multiple job holders). Consequently, it is a more

accurate representation of how many people work in the industry. In contrast,

the Labour Force survey only provides industry employment estimates for people

in their main job. However, Labour Account data does not provide any regional or

state and territory estimates, or estimates of full-time and part-time

employment, or employee access to leave entitlements.

Figure 1 Number of people

employed in the coal mining industry, annualised data, 1994–95

to 2021–22

Source: ABS, Labour Account Australia, (Canberra: ABS, March 2022),

(balanced annual estimates).[14]

ABS Labour Force Survey

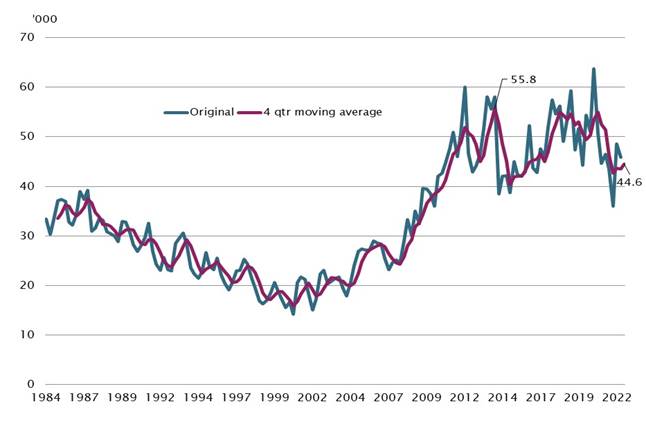

Another source of data for industry

employment is the ABS Labour

Force Survey (LFS). Figure 2 plots an overlaid 4-quarter moving average

of LFS original estimates with the more volatile original quarterly estimates.[15]

The 4-quarter moving average series shows a steady

fall in employment between the mid-1980s and early 2000s before a steady

increase in employment through to a peak of 55,800 achieved in May 2014.

Movements in employment have fluctuated considerably since, with the most

recent estimate being 44,600 in November 2022.

The sample size of the LFS is approximately 50,000

residents living in approximately 26,000 dwellings. Industry employment

estimates from the LFS may be influenced by subjective perceptions and

judgements of survey respondents as to the industry in which household members

work.[16]

For example, the estimates may not capture all labour hire workers or service

contractors that are used in the coal mining industry, in addition to direct

employees, due to confusion as to whether the labour hire company or their host

mining company is the employer.[17]

Figure 2 Employment in coal

mining in Australia—original estimates and average of preceding 4 quarters,

1984 to 2022

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, (Canberra: ABS, June 2022), Datacube

EQ06, 4 quarter moving averages of original data.

LFS data shows the coal industry workforce

is predominantly male with 83.3% of people working in the industry in November

2022 being males working full-time hours. However, the female share of total

employment in the sector has been increasing slowly from 3.9% in November 1985

to 15.7% in November 2022.[18]

ABS Australian Industry

Another source of coal mining employment

data is the ABS Australian

Industry data series. These estimates are produced annually using a

combination of data collected directly from the annual Economic Activity Survey

(EAS) conducted by the ABS, and Business Activity Statement (BAS) data provided

by businesses to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). This data source shows

employment in coal mining has fallen from a peak of 45,016 in June 2012 to 37,335

in June 2021 — a fall of 7,681 or 17.1%. In the 12 months to June 2021

employment in the sector fell by 2,124 or 5.4%.[19]

ABS Jobs in Australia

An additional data source is ABS Jobs

in Australia collected from Australian Taxation Office (ATO)

administrative data that is linked to the ABS Business Longitudinal Analytical

Data Environment (BLADE). This data is sourced directly from employer records

rather than household survey data which increases its accuracy. Some employed

people may be working in multiple jobs in the same industry or in different

industries.

These are not point-in-time estimates. They relate

to the number of jobs recorded over a financial year. There were 50,800 coal

mining jobs recorded over the 12-months from July 2019 to June 2020 (latest

available data at time of writing). This compares with 43,400 recorded in 2018–19,

which is equivalent to an increase of 7,400 or 17.0%. Coal mining jobs

accounted for 0.3% of the approximately 17.9 million jobs recorded across

Australia in 2019–20.

ABS Census of Population and Housing

ABS Census data shows 49,616 people were

employed in coal mining across Australia in 2021. This compares with 46,495

working in the industry in 2016, equivalent to an increase of 3,121 or 6.7%

over 5 years.

Occupations

in the coal industry

Of those employed in the coal industry in

2021, 21,101 were working as Machinery operators and drivers (equivalent to 42.5%

of total employment in the sector); 14,495 (or 29.2%) were Technicians and

trade workers; 5,289 workers (or 10.7%) were Professionals, 3,853 (or 7.8%)

were Managers and 2,351 (or 4.7%) were Clerical and Administrative Workers.

In the five years to 2021 the number of

Technicians and trades workers in the industry grew by 1,013 (or 7.5%), Managers

increased by 781 (or 25.4%) and Professionals grew by 750 (or 16.5%).[20]

The leading occupations in the coal industry

in 2021 were Miners (14,808 or 29.8% of all workers in the industry), Fitters

(General) (5,983 or 12.1%), Electricians (General) (2,639 or 5.3%), Truck

Drivers (General) (2,369 or 4.8%), Mine Deputies (2,051 or 4.1%), Production Managers

(Mining) (1,479 or 3.0%), Metal Fabricators (939 or 1.9%) and Mining Engineers

(excluding Petroleum) (929 or 1.9%).[21]

Approximately 85% of coal mining employment

was concentrated in non–metropolitan areas. Around a third of people working in

managerial and professional occupations in the coal industry were working in

greater metropolitan areas, along with a quarter of clerical and administrative

staff. Well over 90% of Technicians and trades workers, Machinery operators and

Labourers in the industry worked in non–metropolitan areas.

State and territory coal

mining employment estimates

ABS Labour Force Survey

ABS LFS data shows employment in the coal

mining industry is concentrated primarily in the states of Queensland and NSW,

which accounted for 60.0% and 32.2% respectively of total employment in the

industry in November 2022. This source shows 26,800 people employed in the coal

mining industry in Queensland and 14,300 in NSW in November 2022 based on 4

quarter moving averages of original data. There were also 1,700 people employed

in the sector in WA at this time (see Table 1).

Table 1 Employment in the

coal industry by major state/territory, 1985 to 2022

| State/territory |

Nov

1985 |

Nov

2000 |

Nov

2010 |

May

2014 |

Nov

2020 |

Nov

2022 |

Share

of total coal emp in Nov 1985 |

Share

of total coal emp in Aug 2022 |

| ‘000 |

% |

| NSW |

22.2 |

8.3 |

17.9 |

26.7 |

20.2 |

14.3 |

64.3 |

32.2 |

| Vic |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

2.5 |

| Qld |

6.4 |

7.4 |

20.4 |

27.7 |

30.2 |

26.8 |

18.5 |

60.0 |

| SA |

3.4 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

9.9 |

0.7 |

| WA |

1.8 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

0.3 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

5.1 |

3.8 |

| Australia total |

34.6 |

17.0 |

39.8 |

55.8 |

53.4 |

44.6 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Note: Shares in right hand columns may not add up to 100%

due to rounding and exclusion of smaller percentage shares of total coal mining

employment occurring in other states and territories.

Source: ABS, Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, (Canberra: ABS, June 2022),

Datacube EQ06, 4 quarter moving averages

At the peak of coal mining employment in

Australia (using this measure) of 55,800 in May 2014, there were 27,700 people

working in the industry in Queensland and 26,700 working in NSW. Employment has

fallen significantly in NSW since this peak (down 12,400 or 46.4%) while

falling less markedly in Queensland (down 900 or 3.3%).

Over the longer term, the coal mining share

of total employment in NSW has more than halved from 1.0% in August 1985 to

0.3% in November 2022 while the coal mining share in Queensland increased from

0.6% to 1.0%.

ABS Census

ABS Census data shows 20,770 people worked

in coal mining in NSW in 2021 (up 1,881 or 10.0% from 18,889 in 2016), 26,029 were

working in the sector in Queensland (up 808 or 3.2% from 25,221 in 2016) and 1,923

in WA (up 426 or 28.5% from 1,497 in 2016) (see Table 2).[22]

Table 2 Employment

in the coal industry by state and territory, 2016 and 2021

| |

2016

|

2021

|

Number change:

2016 to 2021 |

%

change:

2016 to 2021 |

| NSW |

18,889 |

20,770 |

1,881 |

10.0 |

| Vic |

524 |

448 |

-76 |

-14.5 |

| Qld |

25,221 |

26,029 |

808 |

3.2 |

| SA |

278 |

287 |

9 |

3.2 |

| WA |

1,497 |

1,923 |

426 |

28.5 |

| Tas |

48 |

60 |

12 |

25.0 |

| NT |

29 |

101 |

72 |

248.3 |

| ACT |

3 |

6 |

3 |

100.0 |

| Australia |

46,495 |

49,616 |

3,121 |

6.7 |

Source: ABS,

Census of Population and Housing, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by Place of

Work (the geographic area in which a person worked in the week before Census

night), using TableBuilder.

Jobs in Australia

The ABS Jobs

in Australia data series shows Queensland accounted for the largest

number of coal mining jobs in 2019–20 (at 20,200 or 39.8%) followed by NSW (at

15,500 or 30.5%) and WA (11,600 or 22.8%) (see Table 3).[23]

Coal mining accounted for 0.6% of all jobs

in both Queensland and WA. WA recorded the biggest increase in jobs in coal

mining with 5,000 more in 2019–20 compared to the previous financial year.

Table 3 Coal mining jobs

by state/territory, 2019–20

|

State/territory

|

Number of

coal mining

jobs:

2018–19

|

Number of

coal mining

jobs:

2019–20

|

Total jobs in

all industries:

2019–20

|

Coal mining

share of

total jobs:

2019–20

|

Share of

total coal

mining jobs:

2019-20

|

| |

(no.) |

(no.) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(%) |

| NSW |

16,500 |

15,500 |

5,580,600 |

0.3 |

30.5 |

| Vic |

900 |

1,300 |

4,631,000 |

0.0 |

2.6 |

| Qld |

18,300 |

20,200 |

3,627,200 |

0.6 |

39.8 |

| SA |

500 |

1,500 |

1,153,600 |

0.1 |

3.0 |

| WA |

6,600 |

11,600 |

1,933,100 |

0.6 |

22.8 |

| Tas |

200 |

200 |

365,800 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

| NT |

400 |

400 |

187,200 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

| ACT |

0 |

0 |

356,100 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Australia total |

43,400 |

50,800 |

17,857,800 |

0.3 |

100.0 |

Source: ABS, Jobs in Australia, (Canberra: ABS, November 2022).

Other estimates for coal mining employment in NSW and

Queensland

More data on employment in coal mining in

Queensland is available from the Queensland Government Department of Resources,

Safety and Health, which collects information directly from Queensland mines on

worker numbers on a quarterly basis. This source shows 37,970 people were

working in coal mining in Queensland in June 2022. This compares with 30,952

working in in June 2017. In this 5-year period employment in the industry grew

by 7,018 or 22.7%.[24]

Additional estimates for coal mining

employment in NSW are available from the Coal Services Annual Report[25]

which showed 21,979 full-time equivalent (FTE) workers engaged in coal mining production

employment[26]

in June 2021. This estimate is 682 or 3% less than the previous financial year,

but 2,591 (or 13.4%) more than the estimate of 19,388 FTE workers recorded in

June 2016.

Around 38% of the coal industry workforce in

NSW were reported to be contractors.

Regional coal mining jobs and

employment estimates

ABS Jobs in Australia

The ABS Jobs in Australia series is also a

source of regional data for coal mining. The regions with 1,000 coal mining

jobs or above in 2019–20 are shown in Table 4, along with the coal mining share

of total jobs in each Statistical Area Level 4 (SA4) region.

Table 4 Ranking of coal

mining jobs by SA4 region, 2018–19 and 2019-20

| SA4 Name |

State |

Coal

mining

jobs:

2018–19 |

Coal

mining

jobs:

2019–20 |

Total

jobs:

2019–20 |

Coal mining

share of

total jobs

in SA4:

2019–20 |

| |

|

(‘000) |

(‘000) |

(‘000) |

(%) |

| Hunter Valley excl

Newcastle |

NSW |

7.0 |

6.0 |

189.3 |

3.1 |

| Central Queensland |

QLD |

4.4 |

5.2 |

161.2 |

3.2 |

| Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday |

QLD |

4.1 |

4.5 |

142.8 |

3.2 |

| Newcastle and Lake

Macquarie |

NSW |

2.5 |

2.4 |

265.2 |

0.9 |

| Central West |

NSW |

2.4 |

2.3 |

137.0 |

1.7 |

| Perth–South West |

WA |

1.2 |

2.0 |

323.3 |

0.6 |

| Perth–North West |

WA |

1.0 |

2.0 |

423.8 |

0.5 |

| Perth–South East |

WA |

1.1 |

1.9 |

384.3 |

0.5 |

| Bunbury |

WA |

1.6 |

1.7 |

135.0 |

1.3 |

| Queensland–Outback |

QLD |

2.1 |

1.7 |

56.4 |

3.0 |

| New England and North West |

NSW |

1.4 |

1.5 |

116.3 |

1.3 |

| Wide Bay |

QLD |

1.0 |

1.1 |

173.5 |

0.6 |

| Townsville |

QLD |

1.1 |

1.1 |

178.2 |

0.6 |

| Western Australia–Outback (North) |

WA |

0.1 |

1.1 |

72.4 |

1.5 |

| Perth–North East |

WA |

0.5 |

1.0 |

200.3 |

0.5 |

Source: ABS, Jobs in Australia, (Canberra: ABS, November 2022)

The Hunter Valley region (excluding

Newcastle) in NSW had the most coal mining jobs at 6,000 in 2019–20, which

accounted for 3.1% of all jobs in the region. Other regions with large numbers

of coal mining jobs include Central Queensland (5,200 or 3.2% of all jobs in

the region) and Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday (4,500 or 3.2% of all jobs in the

region). SA4s in the Perth region recorded the biggest 12 monthly increases in

coal mining jobs.

Some of the regional jobs estimates provided

by this data source for 2019–20 are much lower than regional employment

estimates for 2021 that are available from the Census and discussed in the

following section.

ABS Census employment

ABS Census data shows the biggest regional

concentrations of coal mining employment in 2021 were in the SA4s of

Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday (Queensland) at 13,335 (or 14.4% of total employment in

the region) and the Hunter Valley (NSW) at 10,056 (or 8.6% of total employment).

Both regions experienced significant increases in coal mining employment

between 2016 and 2021 with an increase of 3,380 (or 34.0%) in Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday

and an increase of 1,232 (or 14.0%) in the Hunter Valley. In contrast

employment in coal mining fell in Newcastle and Lake Macquarie by 733 or 25.5%

and employment in the industry fell by 662 or 33.1% in Illawarra.

The SA4 of Central Queensland had

significant concentration of coal mining employment in 2021, at 7,349 (or 7.2%

of total employment) and employment in the industry in the SA4 of Brisbane

Inner City increased significantly from 856 in 2016 to 2,443 in 2021 (see Table

5).

Table 5 Major regions for

coal mining employment, 2016 and 2021

| Major SA4s and states |

Coal

mining

(2016) |

Coal

mining

(2021) |

Total

employed

(2021) |

Coal

mining

share of total

employment

(%) 2021 |

| Major SA4s |

| Mackay–Isaac–Whitsunday |

9,955 |

13,335 |

92,309 |

14.4 |

| Hunter Valley |

8,824 |

10,056 |

116,800 |

8.6 |

| Central Queensland |

6,670 |

7,349 |

102,519 |

7.2 |

| Central West |

2,108 |

2,678 |

91,918 |

2.9 |

| Brisbane Inner City |

856 |

2,443 |

364,268 |

0.7 |

| Newcastle and Lake

Macquarie |

2,871 |

2,138 |

179,684 |

1.2 |

| New England and North–West |

1,240 |

1,690 |

77,640 |

2.2 |

| Sydney–Outer South West |

465 |

1,459 |

89,499 |

1.6 |

| Illawarra |

2,000 |

1,338 |

113,940 |

1.2 |

| Bunbury |

702 |

660 |

78,895 |

0.8 |

Source: ABS, Census

of Population and Housing, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by Place

of Work[27]

(Canberra: ABS, 2016), using TableBuilder

Renewable

energy sector and fossil fuel electricity generation

Renewable

energy contribution to total electricity generation

The renewable energy sector in Australia has

a long history dating back to the building of the Waddamana Power Station in

Tasmania in 1916, and the development of the Snowy Mountains Scheme between

1949 and 1974. The Tasmanian hydroelectric scheme currently has 30 power

stations and a capacity of 2,600 megawatts.[28]

The 9 power stations and 33 turbines of the Snowy Hydro scheme have a combined

capacity of 4,100 megawatts.[29]

It is interesting to reflect that the

renewable share of total electricity generation in Australia was as high as

25.7% in 1964–65 when electricity generation from

hydroelectricity schemes operating in the Snowy Mountains and Tasmania was responsible

for a significant share of total electricity generation in Australia. From this

point electricity generation from renewables steadily decreased as a share of

total electricity generation through to 2008–09 when the renewable share reached

a low of 7.5%.[30]

This outcome was largely driven by the steady

increase in electricity generation from fossil fuels such as black and brown

coal, as generation from hydro remained fairly steady during this period, apart

from during drought conditions. The renewable share has since increased sharply

to 26.7% in 2020–21, reflecting the increase in renewable electricity

generation and the decline in generation from fossil fuels.

Figure 3 Renewable

share of total electricity generation in Australia, 1960–61 to 2020–21

Source: Department of Climate

Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2022), Australian Energy Statistics,

Table O; International Energy Agency (2022), World Energy Balances.

Over the two decades to 2020–21 the share of

total electricity generation accounted for by black and brown coal fired power

stations has fallen from 83.4% to 52.8%, while the contribution from natural gas

has increased from 7.7% to 18.7% (see Table 6). Generation from renewables

increased by 52,960.2 GWh or 296.9% over the 20 year period, while generation

from fossil fuels fell by 11,045 GWh or 5.4%.[31]

Table 6 Australian

electricity generation, by fuel type; 2000–01, 2015–16 and 2020–21

| |

Electricity

generation |

Share of total

electricity generation |

| 2000–01 |

2015–16 |

2020–21 |

2000–01 |

2020–21 |

| GWh |

GWh |

GWh |

% of total |

% of total |

| Non-renewable fuels |

|

| Black coal |

134,264.0 |

114,263.0 |

106,251.4 |

60.0 |

40.0 |

| Brown coal |

52,223.0 |

48,827.8 |

34,060.0 |

23.4 |

12.8 |

| Natural gas |

17,271.0 |

50,536.1 |

49,782.9 |

7.7 |

18.7 |

| Oil products |

2,044.0 |

5,655.6 |

4,661.9 |

0.9 |

1.8 |

| Total non-renewable |

205,802.0 |

219,282.5 |

194,756.3 |

92.0 |

73.3 |

| Renewable fuels |

|

| Bagasse, wood[32] |

633.0 |

2,493.4 |

1,992.2 |

0.3 |

0.8 |

| Biogas[33] |

12.0 |

1,296.5 |

1,354.0 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

| Wind |

210.0 |

12,199.5 |

24,535.4 |

0.1 |

9.2 |

| Hydro |

16,933.0 |

15,318.2 |

15,199.7 |

7.6 |

5.7 |

| Large-scale solar PV |

.. |

457.2 |

9,637.9 |

0.0 |

3.6 |

| Small-scale solar PV |

50.0 |

6,381.0 |

18,079.1 |

0.0 |

6.8 |

| Geothermal |

.. |

0.2 |

na |

.. |

.. |

| Total renewable |

17,838.0 |

38,146.0 |

70,798.2 |

8.0 |

26.7 |

| Total |

223,640.0 |

257,428.6 |

265,554.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Department of

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, Australian Energy Statistics, Table O, September 2022.

Note: These are the official

estimates of total electricity generation in Australia. Estimates are derived

from multiple data sources including the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO)

and the Clean Energy Regulator (CER). These statistics cover all electricity

generation in Australia. This includes by power plants, and by businesses and

households for their own use, in all states and territories. This also includes

both on and off grid generation.

The Clean Energy Council reported that

renewable energy sources accounted for 32.5% of Australia’s total electricity

generation in the calendar year of 2021, with small-scale solar adding 3.3

gigawatts of new capacity over 12 months. Large scale wind and solar also added

an additional 3 gigawatts of capacity. Large scale wind accounts for the

greatest share of renewable electricity generation (at 35.9% in 2021), followed

by small-scale solar (24.9%), hydro (21.6%), large-scale solar (12.3%), bioenergy

(4.3%) and medium-scale solar (1.1%).[34]

The Clean Energy Council also flagged that 68

large-scale renewable energy projects were either under construction or

financially committed at the end of 2021. These projects were expected to add a

further 9 GW hours of capacity to the electricity grid as well as creating

35,000 construction and operational jobs. Of these projects 42 were related to

solar, 19 involved wind power generation and the remainder included bioenergy

plants, hydropower projects and hybrid projects. Many of the jobs created will

be in regional areas.[35]

Employment

estimates for the renewable energy sector

In contrast to the coal mining industry,

employment data is more limited for the renewable energy sector. This is due to

the lack of unique industry classification for different forms of renewable

generation activities, apart from Hydro-electricity generation (ANZSIC 2612),

in the ABS industry classification system.[36]

All other forms of renewable energy generation are grouped together in Other electricity

generation (ANZSIC 2619).[37]

As a result, it is not possible to extract separate employment estimates for

the emerging renewable energy forms such as wind, solar, geothermal and tidal

electricity generation from ABS data sources such as the Labour Account, the

Labour Force survey and the Census.

To address this data gap, the ABS has

provided experimental employment estimates for renewable energy activities from

2009–10 to 2018–19 using funding provided by the Australian

Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA). The experimental estimates are not taken

from the ABS Labour Force survey or linked employee-employer data sets.

Consequently, they cannot be compared directly with employment in other

industries such as coal mining. They are based upon information that is

available publicly (including company annual reports, audit reports and company

websites), an employment factor approach (based upon energy capacity and output

of renewable energy infrastructure), and employment numbers provided by

renewable energy operators themselves. A more detailed explanation of how the

ABS calculates its employment estimates in renewable energy activities is

provided in the Appendix at the end of this snapshot.

These experimental employment estimates are

no longer being produced and it is unclear if funding to enable the production

of estimates will be made available in future. This is problematic for analysts

and policy makers hoping to observe and track future employment trends in the

renewable energy sector.

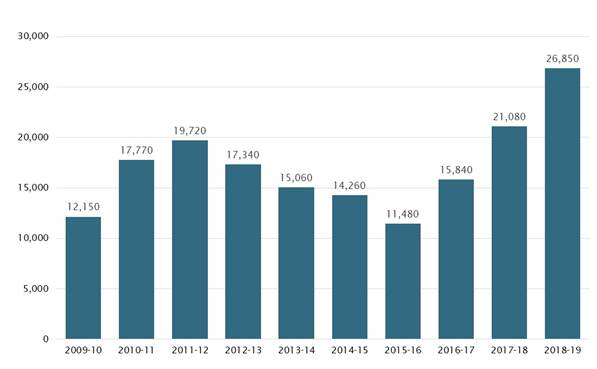

The data collected by the ABS shows there

were 26,850 full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs in renewable energy activities in

Australia in 2018–19, up by 15,370 or 133.9% since 2015–16 (see Figure 4).[38]

Figure 4 FTE employment in

renewable energy activities, 2009–10 to 2018–19

Source: ABS, Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, (Canberra: ABS, April 2020).

In its methodology the ABS tends to

interchange between the terms FTE jobs and FTE employment when describing the

number of employees working in the sector.[39]

In the period between 2015–16 and 2018–19

growth in FTE employment was strongest in large scale solar (up more than

tenfold), followed by wind power generation (which more than quadrupled), and roof

top solar PV (up 121.5%) (see Table 7). Roof top solar PV accounted for the

largest share of total FTE employment in 2018–19 (at 48.7%), followed by large

solar PV (17.7%), wind (12.1%) and hydro (11.4%).

Data from the Clean

Energy Regulator shows the number of rooftop solar PV system installations

across Australia continued to increase steadily each year from 132,697 in 2016

to 377,285 in 2021, which would have stimulated further employment growth in

the sector.[40]

There had been just over 3.3 million solar PV panel systems installed in

Australia between 2001 and November 2022 for either private dwellings or small

businesses under the Small-scale

Renewable Energy Scheme.

Table 7 FTE employment by

renewable energy type, selected years from 2009–10 to 2018–19

| Energy type |

2009–10 |

2012–13 |

2015–16 |

2018–19 |

Change: 2015–16

to 2018–19 |

Share

of total FTE

in 2018–19 |

| (no.) |

(%) |

(%) |

| Roof top solar PVa |

6,900 |

11,000 |

5,900 |

13,070 |

7,170 |

121.5 |

48.7 |

| Solar PV Large |

10 |

140 |

410 |

4,740 |

4,330 |

1,056.1 |

17.7 |

| Wind power |

1,090 |

1,440 |

770 |

3,240 |

2,470 |

320.8 |

12.1 |

| Hydro |

1,860 |

2,310 |

1,870 |

3,060 |

1,190 |

63.6 |

11.4 |

| Biomass |

1,440 |

1,440 |

1,500 |

1,580 |

80 |

5.3 |

5.9 |

| Geothermal |

110 |

70 |

40 |

40 |

0 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

| Govt/NPIb |

740 |

940 |

990 |

1,120 |

130 |

13.1 |

4.2 |

| Total |

12,150 |

17,340 |

11,480 |

26,850 |

15,370 |

133.9 |

100.0 |

a Includes solar hot water systems.

b NPIs are non-profit institutions, that are institutionally

separate from government and self-governing.

Source:

ABS, Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, (Canberra: ABS, April 2020).

NSW accounted for the biggest share of FTE

employment in renewable energy activities (28.9%) in 2018–19, followed by

Queensland (23.6%) and Victoria (22.7%). FTE employment in renewable energy

activities increased at the fastest rate in SA in the 3 years between 2015–16

and 2018–19, up 241.3%, followed by Victoria and NSW, up 185.9% and 165.4%

respectively (see Table 8).

Table 8 FTE employment in

renewable energy activities by state and territory, selected years from 2009–10

to 2018–19

| State or territory |

2009–10 |

2012–13 |

2015–16 |

2018–19 |

Change:

2015–16 to

2018–19 |

Share

of total

renewable energy

employment,

2018–19 |

| (no.) |

(%) |

(%) |

| NSW |

3,760 |

3,750 |

2,920 |

7,750 |

4,830 |

165.4 |

28.9 |

| Vic |

1,730 |

2,920 |

2,130 |

6,090 |

3,960 |

185.9 |

22.7 |

| Qld |

2,770 |

5,030 |

2,800 |

6,330 |

3,530 |

126.1 |

23.6 |

| SA |

1,400 |

1,880 |

750 |

2,560 |

1,810 |

241.3 |

9.5 |

| WA |

1,020 |

1,580 |

1,060 |

1,690 |

630 |

59.4 |

6.3 |

| Tas |

960 |

1,540 |

1,160 |

1,560 |

400 |

34.5 |

5.8 |

| NT |

70 |

70 |

100 |

190 |

90 |

90.0 |

0.7 |

| ACT |

440 |

570 |

560 |

680 |

120 |

21.4 |

2.5 |

| Australia |

12,150 |

17,340 |

11,480 |

26,850 |

15,370 |

133.9 |

100.0 |

Source: ABS, Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, (Canberra: ABS, April 2020).

Note: Estimates include workers involved in construction and

installation as well as ongoing operations and maintenance.

Ongoing operational employment

in renewable energy activities

Table 9 shows the number of ongoing FTE

operational staff engaged in wind and solar, hydro and bio-mass energy

generation and maintenance (as distinct from construction and installation) in

selected years between 2009–10 and 2018–19. The estimates are a subset of the

estimates provided in Table 7. The ABS has provided these unpublished estimates

to the Parliamentary Library based on the data it has collected on renewable

energy activities.

There were 5,750 FTE jobs involved in

ongoing operational renewable energy generation and maintenance activities in

2018–19 with hydro being the biggest employer (at 3,060 FTE jobs). Ongoing

operational employment in wind and solar increased by 690 or 164.3% between

2015–16 and 2018–19 (see Table 9).

The acceleration of employment in wind and

solar in the last 3 years (2015–16 to 2018–19) is due mainly to the increase in

large scale solar PV generation capacity completed over this time.

Table 9 FTE ongoing

operational employment by energy type, selected years from 2009–10 to

2018–19

| Renewable

energy type |

2009–10 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2015–16 |

2018–19 |

Change:

2015–16 to 2018–19 |

| (No) |

(%) |

| Wind and solar |

170 |

250 |

290 |

420 |

1,110 |

690 |

164.3 |

| Hydro |

1,860 |

1,910 |

2,300 |

1,870 |

3,060 |

1,190 |

63.6 |

| Biomass |

1,460 |

1,460 |

1,460 |

1,520 |

1,580 |

60 |

3.9 |

| Total |

3,490 |

3,620 |

4,050 |

3,810 |

5,750 |

1,940 |

50.9 |

Source: ABS data on request, Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, (Canberra: ABS, April 2020).

Employment

in fossil fuel and renewable electricity generation

Table 10 shows the number of people employed

in different forms of electricity generation in 2016 and 2021 by state and

territory as reported in the ABS Census of Population and Housing.

Table 10 Number of people

employed in electricity generation by energy type by state and territory, 2021

| State/ territory |

Electricity

generation,

nfd |

Fossil fuel

electricity

generation |

Hydro-electricity

generation |

Other

electricity

generation (a) |

TOTAL |

| |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

| NSW |

51 |

68 |

1,659 |

1,231 |

342 |

465 |

257 |

538 |

2,316 |

2,303 |

| Vic |

33 |

78 |

1,877 |

1,349 |

103 |

172 |

199 |

533 |

2,214 |

2,129 |

| Qld |

35 |

31 |

1,944 |

2,057 |

124 |

363 |

149 |

329 |

2,250 |

2,776 |

| SA |

41 |

25 |

381 |

317 |

4 |

9 |

111 |

260 |

532 |

610 |

| WA |

43 |

29 |

1,282 |

1,379 |

0 |

4 |

108 |

118 |

1,435 |

1,526 |

| Tas |

10 |

11 |

62 |

52 |

529 |

701 |

8 |

25 |

607 |

792 |

| NT |

15 |

0 |

846 |

235 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

10 |

875 |

245 |

| ACT |

0 |

9 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

4 |

21 |

61 |

27 |

90 |

| Australia |

234 |

248 |

8,065 |

6,630 |

1,112 |

1,718 |

866 |

1,868 |

10,268 |

10,468 |

(a) includes biomass, geothermal, solar, tidal and wind.

nfd = not further defined due to lack of information

provided.

Note: The sum of individual energy types may differ slightly

to totals shown in the right-hand column of the table.

Source: ABS, Census of

Housing and Population, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by Place of Work, using

TableBuilder.

A big fall in employment was recorded in

fossil fuel electricity generation across Australia between 2016 and 2021 – down

1,435 or 17.8% to 6,630.

Fall in employment in fossil fuel

electricity generation were more pronounced in Victoria (down 528 or28.1%) and

NSW (down 428 or 25.8%).

However, employment in fossil fuel

electricity generation did increase in Queensland (up 113 or 5.8%) and Western

Australia (up 97 or 7.6%). Overall, the increase in employment in all forms of

electricity generation across Australia in the 5 years to 2021 was modest at

200 or 1.9%.

Employment in hydroelectricity electricity

generation increased by 606 or 54.5% to 1,718, while employment in other forms

of renewable electricity generation increased by 1,002 or 115.7% to 1,868.

Employment in all forms of renewable

electricity generation across Australia increased from 1,978 in 2016 to 3,586

in 2021—an increase of 1,608 or 81.3%.

Total renewable electricity generation

(hydro plus other) accounted for 34.3% of total employment in electricity

generation in Australia in 2021. This compares with a 19.2% share in 2016.

Around 2.4% of employment in the industry could not be classified to either

fossil fuels or renewables in 2021.

Some jurisdictions had much higher

concentrations of employment in electricity generation using fossil fuels in

2021 including the Northern Territory (95.9%) and WA (90.1%). The fossil fuel

electricity generation share of total employment in electricity generation in

Queensland has fallen from 86.3% in 2016 to 74.0% in 2021, while the share

recorded in Victoria fell from 84.9% to 63.3%. Tasmania relies heavily on hydroelectricity

which is reflected in the sector’s 88.8% share of total electricity generation

employment. SA experienced a more than doubling in the other renewable electricity

generation share of total electricity generation employment from 20.7% to 42.6%

(see Table 11).

Table 11 Percentage of share

of total people employed in electricity generation by type and state and

territory, 2016 and 2021

| |

Electricity

generation nfd |

Fossil fuel

electricity

generation |

Hydro-electricity

generation |

Other

electricity

generation (a) |

TOTAL |

| |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

2016 |

2021 |

| |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

|

| NSW |

2.2 |

3.0 |

71.8 |

53.5 |

14.8 |

20.2 |

11.1 |

23.4 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Vic |

1.5 |

3.7 |

84.9 |

63.3 |

4.7 |

8.1 |

9.0 |

25.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Qld |

1.6 |

1.1 |

86.3 |

74.0 |

5.5 |

13.1 |

6.6 |

11.8 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| SA |

7.6 |

4.1 |

70.9 |

51.9 |

0.7 |

1.5 |

20.7 |

42.6 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| WA |

3.0 |

1.9 |

89.5 |

90.1 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

7.5 |

7.7 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Tas |

1.6 |

1.4 |

10.2 |

6.6 |

86.9 |

88.8 |

1.3 |

3.2 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| NT |

1.7 |

0.0 |

96.8 |

95.9 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

4.1 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| ACT |

0.0 |

10.5 |

0.0 |

14.0 |

0.0 |

4.7 |

100.0 |

70.9 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Australia total |

2.3 |

2.4 |

78.5 |

63.4 |

10.8 |

16.4 |

8.4 |

17.9 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

(a) includes biomass, geothermal, solar, tidal and wind.

nfd = not further defined.

Source: ABS, Census

of Housing and Population, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by Place of

Work, using TableBuilder.

Census data shows 45.9% of employment from

electricity generation using fossil fuels is based in Greater metropolitan

areas with 52.3% based in non-metropolitan regions. An additional 1.8% reported

no fixed address as their place of work in the week before the Census night. In

comparison 60.5% of employment in electricity generation using renewables was

based in Greater metropolitan areas, with 35.9% based in non–metropolitan areas,

while 3.6% reported no fixed address for their place of work in the week before

the Census night. The high percentage of employed people in renewable forms of

electricity generation in metropolitan areas is likely to be related to the

labour-intensive installation of solar panels on private residences in more

densely populated cities.

Other estimates for employment

in renewables and projections for future employment

The University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Institute

for Sustainable Futures (the Institute) undertook some analysis for the Clean

Energy Council in June 2020 in which it provided a current estimate for FTE

employment/jobs in the renewables sector and projections for employment growth

under a range of scenarios.[41]

Surveys were undertaken for large-scale

solar PV and wind power, distributed solar PV, hydro generation and pumped

hydro, battery storage, and the associated supply chains. Using employment

factors derived from these surveys, estimates of renewable energy jobs from

2020 to 2035 were produced using three energy market scenarios and other inputs

from the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) Integrated System Plan

(AEMO 2020) for the eastern states:

- Central Scenario: growth is determined by market forces under

current federal and state government policies (i.e. business-as-usual with no

additional policy)

- Step Change: strong policy commitments occur with ‘aggressive

decarbonisation’ and growth in renewable energy.[42]

- High Distributed Energy Resource (DER): higher growth in rooftop

solar and battery storage relative to large-scale renewable energy.

Similar to the methods used by the ABS to

calculate FTE, the methodology used by the Institute to calculate employment

estimates uses a combination of industry survey data and an employment factor

methodology:

Simply put, an employment factor (full-time equivalent

jobs/megawatt of installed capacity) is derived from industry surveys and

applied to the level of installed capacity (MW) to estimate total employment.

The employment factor is reduced over time to reflect productivity

improvements.[43]

The authors estimate there were around

26,000 FTE jobs in the renewable energy sector across Australia in 2020 (prior

to the impact of COVID-19). The report tends to use the terms ‘employment’ and ‘jobs’

interchangeably. whereas the ABS traditionally presents labour estimates where

an ‘employed’ person may have one or more ‘jobs’. For simplicity, it may be

interpreted that the estimates refer to the number of FTE jobs in the renewable

energy sector.

Under the Step scenario that assumes strong

policy commitments which are consistent with the Paris Climate Agreement in

tandem with accelerated exits of coal generators, FTE jobs in the renewable

energy sector peaks at around 45,000 in 2025, and them moderates to around 34,400

in 2035.[44]

Under the High Distributed Energy Resource

(HDER), in which there is a higher growth in rooftop solar and battery storage

relative to large-scale renewable energy, it estimates that FTE jobs remains relatively

stable at around 30,000 between 2024 and 2027, but then accelerates, and could

be as high as 45,000 in 2035. If this scenario eventuates employment in

renewable power generation would be 19,000 or 73.1% higher than the current estimate

of 26,000 for 2020.[45]

A Central scenario assumes the status quo

whereby current federal and state government policies are allowed to continue

unchanged and market forces determine growth in use of renewable sources of

energy. Under this scenario FTE jobs would drop from 26,000 currently to around

15,000 in the mid-2020s and would not substantially recover to the 2020 level

until around the mid-2030s.[46]

The expectation that employment would fall under the Central scenario is based

on a forecast hiatus in the industry associated with low levels of new

installation. Employment was then expected to remain flat for the next five

years. However, the increase in renewable capacity and generation noted earlier

in this report in 2021 would appear to contradict this prediction.

The Institute projects that around two

thirds of FTE jobs generated in renewable energy between 2020 and 2035 could be

in regional areas, with some variation between states and territories depending

upon their technology mix.[47]

In terms of the ability of renewable energy to replace jobs

that could be lost in coal mining and electricity generation using fossil fuels

in regional areas the authors’ state:

… renewable energy cannot replace the loss of jobs in coal mining

- but the sector can play a meaningful role in creating alternative employment

within a wider regional industry development strategy that builds a range of

industries as the coal sector declines.[48]

Regions that mine metallurgical coal for

steel production are likely to be less vulnerable to job loss than regions

involved in mining thermal coal. However, the emergence of steel making

technologies that are less reliant on metallurgical coal are likely to have an

impact on demand for coal mining into the future. The Institute suggests the

growth of ‘green steel’ technologies and electric arc furnaces in South-East

Asia could reduce demand for metallurgical coal over time.[49]

In terms of additional data sources for

employment in the renewable energy sector the Department of Industry, Science,

Energy and Resources is conducting a national energy workforce survey which

will shed light on the types of jobs that exist in the energy sector, and the

characteristics and skills of people working in the sector. The first survey of

businesses in the energy sector is expected to be undertaken at the end of

January 2023, with the findings being used to produce the Australian Energy

Employment Report (AEER).[50]

Conclusion

There are a several estimates available for

employment in coal mining using different data sources. Some sources show

employment in the coal mining industry has fallen substantially since its most

recent peak.[51]

In contrast, ABS Census data shows employment growth of just under 7% between

2016 and 2021.

The prospects for employment in coal mining

are uncertain despite the likelihood of continued strong global demand for

metallurgical coal used in steel making. Much will depend on the strength of

demand for thermal coal in the short to medium term as Australia and other

countries make decisions on their preferred energy mix between fossil fuels and

renewables.

ABS data shows a significant fall in direct

FTE employment in renewable energy activities between 2011–12 and 2015–16, but a

strong recovery in the following three years to 2018–19 in response to the

building of large scale solar and wind farms and high rates of take up of

rooftop solar PV. However, employment estimates for 2018-19 were the last to be

published by the ABS using this data source.

ABS Census data shows strong growth in

employment in renewable energy electricity generation between 2016 and 2021,

with an increase of just over 1,600 or 81.3%. In comparison, employment in

electricity generation using fossil fuels fell by 1,435 or 17.8%.

There is potential for further growth in

rooftop solar as the cost of producing solar panels continues to fall, as

batteries and other enabling technologies improve, and in response to policy

initiatives aimed at encouraging households to install rooftop solar. The rate

of rooftop installations in future is also likely to respond to future changes

in retail electricity prices.[52]

Prospects for increased employment in the renewable

electricity generation sector will continue to be heavily influenced by the

level of government support for the sector in the future and the rate of

transition away from the use of fossil fuels for electricity generation.

Appendix

ABS Methodology for

calculating renewable energy employment

The following information is taken from the methodology

for the ABS publication Employment in Renewable Energy Activities.

Direct employment in renewable energy

activities is related to the production of renewable energy, and/or by the

design, construction and/or maintenance of renewable energy infrastructure.

The ABS used a range of techniques in compiling

these employment estimates including sourcing information from annual reports,

media reports and industry associations. The ABS also used employment numbers

provided directly by institutions and organisations as well as an employment

factor approach in deriving their estimates.

The employment factor approach looks at the

amount of potential renewable energy produced by different sources as well as

the generation infrastructure including the size and number of installations in

determining employment estimates. Size is the amount of energy generated as

measured in megawatts (MWs) for aggregated roof-top units, larger scale wind

and solar operations. Employment factors indicate the number of annual direct

full-time jobs created per physical unit of choice, for example, numbers of

annual FTE employees created per megawatt (MW) of installed capacity of wind

power. It is an estimation technique that has been used internationally to

generate employment numbers associated with renewable energy activities

It could be assumed that the installation of

more units on roofs of houses by small and medium-sized contractors or

construction of large solar and wind generating plants will result in greater

direct employment during the installation or construction phase.

Employment estimates for solar and wind

sources of renewable energy relied heavily on the employment factor approach

whereas all other forms of renewable energy generation rely on publicly

available information from the producers themselves.

An additional renewable energy activity

covered by employment estimates is employees of government bodies and

non-profit institutions (NPIs). The ABS considers the estimates published are

likely to understate the true levels of renewable energy employment within

government and NPIs. It is likely that a significant number of these entities

employ people engaged in work directly related to renewable energy. For

example, more accurate estimates could include local council employees that

develop and administer guidelines related to rooftop solar systems, or

employees of state government agencies that manage environmental aspects of

wind farm proposals.

Some government and NPI employees are

engaged in climate change related work such as climate change policy

development, advice, training and inter-disciplinary collaboration. Although

renewable energy is a central consideration of climate change policy, these

employees are not specifically engaged in renewable energy activities and are

excluded from the FTE estimates provided by the ABS. However, the estimates do

include research and development activities related to renewable energy

undertaken by universities, often in partnership with outside entities.

[1] Original data

are estimates that have not been seasonally adjusted or trended.

[2]. Coal Services

is a health and safety scheme that provides services to identify, assess,

monitor and control risks in workplaces in the NSW coal mining industry.

[3] Department of

Industry, Science and Resources, Resources

and Energy Quarterly, December 2022, p. .57 and p. 69.

[4] Australian

Bureau of Statistic (ABS), International

Trade in Goods and Services, Australia, Tables 1 and 12b.

[5] Department of

Industry, Science and Resources, Resources

and Energy Quarterly, December 2022, p. .50 and p. 60.

[6] Department of

Industry, Science and Resources, Resources

and energy quarterly: December 2022 – historical data [XLSX], table 24 (2).

[7]. Australian

Bureau of Statistic (ABS), Australian

System of National Accounts (Canberra: ABS, 2021), Table 5.

[8]. IVA is an

estimate of the difference between the market value of the output of an

industry and the purchases of materials and expenses incurred in the production

of that output.

[9]. Australian

Bureau of Statistic (ABS), Australian

Industry, (Canberra, ABS, 2022), Table 3. Selected industries exclude

Finance and insurance and government enterprises.

[10] The Labour

Account employment estimates are balanced annual estimates to the end of June

of each year.

[11] Australian

Bureau of Statistic (ABS), Labour

Account, (Canberra, ABS, 2022).

[12] The Labour

Account draws on data from the Australian National Accounts: National Income,

Expenditure and Product; Quarterly Business Indicators Survey (QBIS); Economic

Activity Survey (EAS); Survey of Employment and Earnings (SEE); Labour Force

Survey (LFS); Survey of Employee Earnings and Hours (EEH) and Linked

Employer-Employee Database (LEED).

[13]. The industry

classification for coal mining is taken from the ABS Australia and New Zealand Industry

Classification (ANZSIC). Coal mining consists of business units engaged in

open-cut or underground mining of black or brown coal.

[14]. Balanced

estimates result from incorporating data sourced from businesses and

households.

[15]. Original

estimates are the actual estimates the ABS derives from the survey data. These

estimates have not had a seasonal adjustment process applied to remove

the effects of systematic calendar related patterns or been smoothed using a

trending process. The moving 4 quarter average is used to smooth out volatility

from quarter to quarter.

[16]. ABS, Labour

Force, Australia methodology, (Canberra: ABS, 2022).

[17] Deloitte Access

Economics, Economic

effects of changes to labour hire laws, June 2019, p. 29.

[18] Based on 4

quarter moving averages of original estimates from the ABS Labour Force Survey.

[19]. ABS, Australian

Industry, (Canberra: ABS, 2022). The data series uses a combination of data

collected directly from the annual Economic Activity Survey (EAS) conducted by

the ABS, and Business Activity Statement (BAS) data provided by businesses to

the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

[20] ABS,

Census of Population and Housing, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by

Place of Work (the geographic area in which a person worked in the week before

Census night), using TableBuilder.

[21] ABS, Census

of Population and Housing, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), using

TableBuilder.

[22] ABS, Census

of Population and Housing, (Canberra: ABS, 2016 and 2021), by Place of

Work, using TableBuilder.

[23]. The

Jobs in Australia data series draws on the Linked Employer-Employee Dataset

(LEED), which is built using ATO administrative data linked to ABS Business

Longitudinal Analytical Data Environment (BLADE).

[24] Resources

Safety and Health Queensland, Qld

quarterly mine and quarry safety data.

[25] Coal

Services Annual Report, 2020-21, p. 35.

[26] Production

employment includes working proprietors and persons engaged as employees of the

operator of the mine. The estimates also include employees of contractors

undertaking work relating to coal production, coal preparation, overburden

removal; drivers transporting coal from the mine to a preparation plant; and

people engaged in administration/clerical work at the mine site.

[27] Place of Work records

the geographic area in which a person worked in the week before Census night.

[28] ‘About us’, Hydro Tasmania.

[29] The

Snowy Scheme’, Snowy Hydro.

[30] Department

of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian

Energy Update 2022 data for charts, Figure 18.

[31] Department

of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian

Energy Update 2022 data for charts, Figure 15.

[32] Bagasse is the

dry pulpy fibrous material that remains after crushing sugarcane or sorghum

stalks to extract their juice. It is used as a biofuel in the production of

heat, energy, and electricity, and in the manufacture of pulp and building

materials.

[33] Biogas is produced

from the anaerobic (oxygen free) digestion (or degradation) of organic matter.

It can be made from a large variety of organic resources, including industrial

waste, agricultural waste, energy crops, sludge from waste water treatment and

biowaste. Biogas is a source of energy that can be converted into heat or

electricity.

[34] Clean Energy

Council, Clean

Energy Australia Report 2022, (Melbourne: Clean Energy Council, 2022), p.

10.

[35] Clean Energy

Council, Clean

Energy Australia Report 2022, (Melbourne: Clean Energy Council, 2022), p.

19.

[36]. ABS, Australia and New Zealand Industry

Classification (ANZSIC), (Canberra: ABS, 2013).

[37]. Other

electricity generation aggregates together Biomass electricity generation not

elsewhere classified (nec), Electricity generation nec, Geothermal electricity

generation, Solar electricity generation, Tidal electricity generation and Wind

electricity generation.

[38]. ABS,

Employment

in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia,

(Canberra: ABS, 2020).

[39]. ABS,

Employment

in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia methodology, (Canberra: ABS,

2020).

[40] ‘Postcode

data for small-scale installations’, Small-scale installations by

installation year, Clean Energy Regulator.

[41]. C.

Briggs, J. Rutovitz, E. Dominish and K. Nagrath, Renewable

Energy Jobs in Australia: Stage 1, report prepared for the Clean Energy

Council by the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology

Sydney (UTS), (Sydney: UTS, 2020).

[42] A Step change is

defined in business or politics as a significant change in policy or attitude.

[43]. Briggs

et al, p. 22.

[44] Briggs et al, p.

4.

[45] Briggs et al, p.

4.

[46] Briggs et al, p.

4.

[47]. Briggs

et al, p. 39.

[48]. Briggs

et al, p. 42.

[49]. Briggs

et al, p. 42.

[50]. J.

Rutovitz, D. Visser, S Sharpe, H. Taylor, K. Jennings, A. Atherton, C. Briggs, F.

Mey, S. Niklas, A. Bos, S. Ferraro, F. Mahmoudi, S. Dwyer, D. Sharp, and G. Mortimer,

Developing

the future energy workforce: Opportunity assessment for RACE for 2030, (Sydney:

UTS, 2021), p. 10.

[51]. The ABS Australian

Industry publication shows a decline in coal mining employment of 17.1%

between June 2014 and June 2021, the ABS Labour Account shows a fall of 26.2%

between 2013-14 and 2021-22, and the ABS Labour Force survey shows a

fall of 20.1% between May 2014 and November 2022.

[52]. R. Best, P.

Burke and S. Nishitateno, Evaluating

the effectiveness of Australia’s Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme for

rooftop solar, (working paper, 1903, Centre for Climate and Energy

Policy, Australian National University, Canberra, 2019), p. 2

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons