16

November 2020

PDF version [1.4MB]

Rory Haupt

and Liz Wakerly

Statistics and Mapping and

Economic Policy Sections

The media regularly reports the findings of various

indexes that seek to quantify the comparative performance of countries in

relation to specific areas as varied as happiness or economic competitiveness.

This Quick Guide brings together the findings of a selection

of these indexes to give a snapshot of how Australia compares internationally.

The indexes are arranged alphabetically according to subject and each entry

summarises what is being measured, where Australia ranks in the comparison and

provides a short analysis of the result and the underlying methodology. Entries

conclude with a list of similar or related measures.

These indexes are inevitably imperfect measures, as their

authors frequently acknowledge. Nevertheless, provided their limitations are

understood, they do provide an interesting summary of how Australia compares

relative to other nations. In that context, the indexes that follow show

Australia to be among the best performing countries in areas ranging from

health to security.

Contents

Introduction

1. Agriculture and food

Global Food Security Index

2. Aid and charity

Commitment to Development Index

3. Competitiveness and globalisation

Global Competitiveness Report

4. Corruption

Corruption Perceptions Index

5. Education

Programme for International Student

Assessment

6. Environment

Environmental Performance Index

7. Health

Global Health Security Index

8. Human Rights

Freedom in the World Index

9. Inequality

OECD Income Inequality

10. Innovation, science &

technology

Global Innovation Index

11. Politics and democracy

Democracy Index

12. Press freedom and the rule of law

World Press Freedom Index

13. Renewable energy

Renewable Energy Country

Attractiveness Index

14. Security and safety

Safe Cities Index

15. Tourism

The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness

Index

16. Well-being and happiness

World Happiness Report

Introduction

An increasing number of quantitative assessments of national

characteristics have emerged over time. Many of these assessments come in the

form of indexes: a combination of measures weighted to provide an overall

indicator in an area of interest. Indexes are generally comprised of a number

of statistical measures, as opposed to, for example, Gross Domestic Product

which is a single statistic. As such, as outlined in this paper, indexes can be

advantageous when assessing broader areas which often contain a number of

complex inputs. For example, how can we measure freedom as a whole, when

freedom can be represented in many different ways?

There are, however, limitations to the usefulness of indexes

insofar as they often require complex calculations and the weighting of

different components is usually chosen subjectively.

Selecting indexes based on their simplicity, suitability and

accessibility, analysis of each is broken down into four parts:

-

an outline of the index, and where Australia ranks

-

an in depth look into what the index measures including the

statistical inputs and methodology

- general commentary including further discussion of how Australia

performs, as well as an assessment of any advantages or critiques and

- a list of complementary indexes or statistics.

To facilitate the search for relevant indexes, they are

presented in alphabetical subject order.

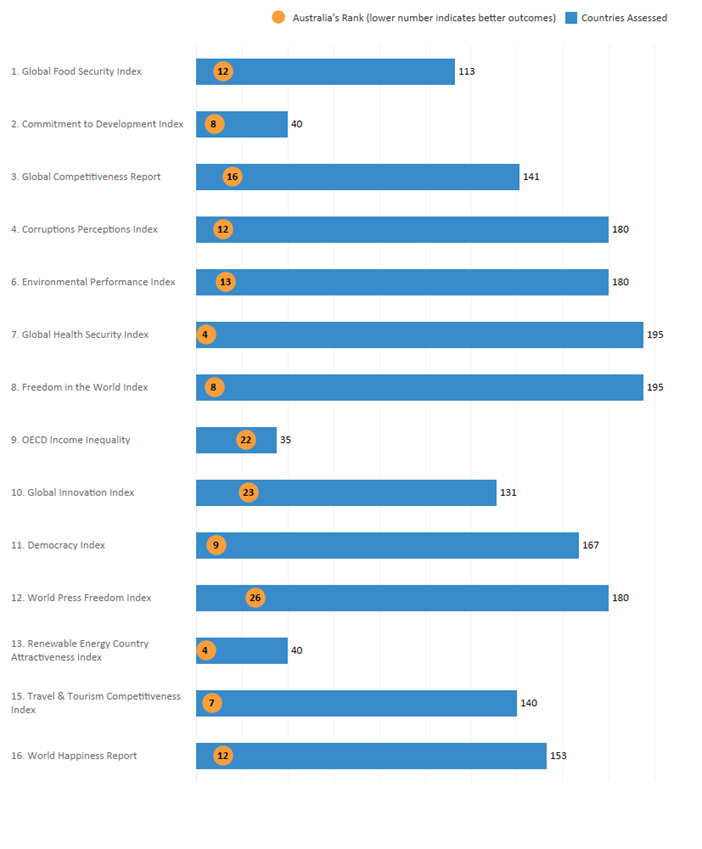

Figure 1: Australia's rankings in indexes

Note: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library. Sources shown throughout

paper.

1. Agriculture and food

Global Food Security Index

The most recent release of The Economist Intelligence

Unit’s Global Food

Security Index occurred in 2019. The index measures food security in a

country, where food security is defined as:

the state in which people at all times have physical, social

and economic access to sufficient and nutritious food that meets their dietary

needs for a health and active live.

The index is measured with reference to the three factors

of food security: affordability; availability; and quality and safety of food,

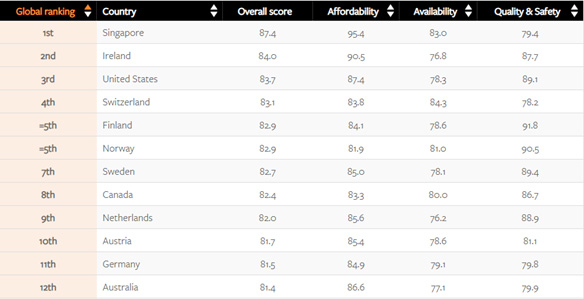

assessing food security amongst 113 countries. In the most recent rankings,

Australia is one of the leading nations in food security, ranking 12th in

the world with a score of 81.4 points. This represents a drop in the

rankings by 6 spots from the previous year.

Figure 2: Global Food Security Index—Rankings

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit, Global Food Security Index:

Rankings and trends, 2019, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The Global Food Security Index takes into account

three different areas relating to food security: affordability; availability;

and quality and safety. Each area has a set of indicators which generate a

score for each country. These include factors spanning agriculture, consumption

and diversification. The overall ranking is a simple weighted average of the

three categorical rankings. Also available as part of the rankings is an adjustment

factor, which assesses the impact of climate change on the food security of

each country, informed by natural resources and resilience rankings. The

adjustment factor identifies which countries are expected to experience an

improvement in rank, or no change, or deterioration due to the effects of

climate change. For Australia, climate change is expected to lead to a

deterioration in rank, likely due to the nation’s susceptibility to

drought, bushfires and others natural disasters.

Commentary

A 2017 report from the European Commission’s Joint

Research Centre assesses the use

of the Global Food Security Index for assessing food security in

countries of interest. The report highlights a number of shortfalls of the

index. As the report notes, the indicators included in the index only assess a

subsection of food security determinants, with data that varies in age across

both countries and indicators. The example is used of 2015-16 El

Niño-damaged countries receiving better ranks than expected as such

impacts were not accounted for (p. 3). The index is comprised of indicators

assessing contributing factors of food security, as opposed to the outcomes

themselves, and as such, does not assess all factors of food security (p. 45).

A comparison with similar indexes shows both strong correlations and variations

(p. 42). The report concludes that the index is used best in conjunction with

other indicators which measure outcomes of food security. For a

more traditional measure, see food

security indicators by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations. For a broader snapshot of a nation’s agriculture industry, data

are available from The

World Bank.

2. Aid and charity

Commitment to Development Index

The Center for Global Development’s Commitment to Development Index,

or CDI, provides a measure of the level of a state’s contribution to

global development through a variety of factors. The CDI assesses 40 countries

in seven areas—finance, environment, security, aid, technology, trade and

migration—and ranks the nations based on an overall score. In the 2020

rankings, Australia achieved a score of 70 overall, ranking it 8 out of 40

countries. This is an improvement from the 2018 index, when Australia was

ranked 14th out of the 27 countries assessed. Australia has strengths in

investment, trade and technology, but achieved a relatively low score in the

environment category, where it ranks it 37 out of 40 countries.

What

does it measure?

Each of the seven broad areas identified above is assessed

based on a number of sub-components, each, in turn, comprising various

indicators. For example, the finance score is provided by two subcomponents,

investment and financial secrecy, each of which is summarised by various

indicators, such as international investment agreements and bilateral treaties.

In order to achieve a similar measure across indicators and the seven

components, scores are standardised to percentiles, with the best performing

country in an indicator receiving 100 and the worst performing country

receiving zero. Each of the seven components is weighted equally in the final

rankings.

Commentary

The CDI provides a broad overview of a country’s

contribution to global development in several important areas. While the index

only includes 27 countries, all are OECD countries and, as such, the rankings

represent most of the developed countries in the world. An expansion of the

rankings would prove useful, potentially providing an indicator of the

willingness of emerging economies, such as India and Brazil, to commit to

global development. Such an expansion may, however, face difficulties relating

to collection of data and quality control. In terms of charity specific

indexes, the Aid

Transparency Index provides a useful measure of the use of aid across 45

aid organisations, ranging from development agencies, such as the United

Nations Development Programme, to state-based aid providers, such as

Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

3. Competitiveness and

globalisation

Global Competitiveness Report

The World Economic Forum’s Global

Competitiveness Report was most recently released in 2019. The

report analyses and measures the competitiveness performance of 141 countries,

measured through 12 ‘pillars’. The report defines competitiveness

as:

… the set of institutions, policies, and factors that

determine the level of productivity of a country. (p. xiii)

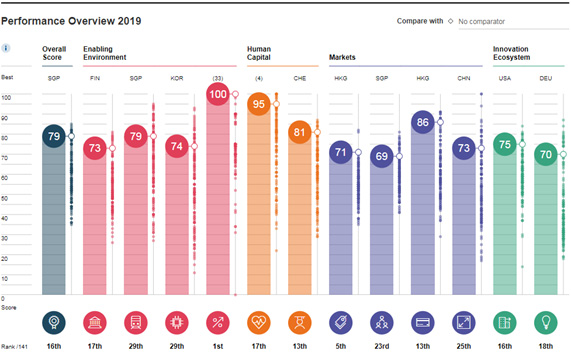

Australia ranked 16th in the Global Competitiveness Index

with a score of 78.7. This is a drop in two spots since the previous year,

despite a reduction in score of only 0.2 points. Figure 3 highlights

Australia’s performance across the pillars, identifying the best

performing country (above score) and how Australia ranks (below score).

Figure 3: Global Competitiveness Report: Australia

Source: World Economic Forum, Global

Competitiveness Report 2019: Australia, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The Global Competitiveness Report uses 12 pillars to

assess competitiveness: institutions; infrastructure; ICT (information and

communication technologies) adoption; macroeconomic stability; health; skills;

product market; labour market; financial system; market size; business

dynamism; and innovation capability. Each pillar is weighted equally. Each of

the pillars is comprised of a number of sub-pillars, also equally weighted,

with scores for sub-pillars determined through numerous indicators. There are

98 indicators across the 12 pillars, with 54 based on statistics, such as mean

years of schooling; and 44 qualitatively based, such as an assessment of

property rights.

Commentary

The Global Competitiveness Report examines a wide

range of contributing factors. Any measure of competitiveness will involve

complexity, and as such a single index will be required to make concessions in

order to provide simplicity. The value of such an index is that it provides comparability

across nations.

4. Corruption

Corruption Perceptions Index

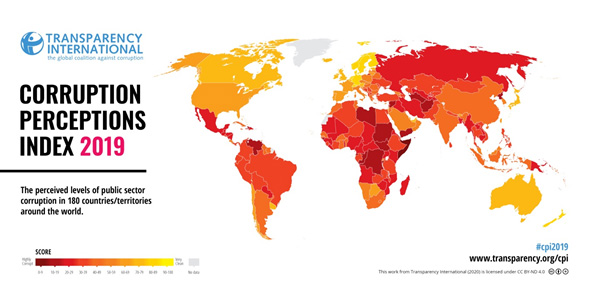

The most recent release of Transparency

International’s Corruption

Perceptions Index (CPI) occurred in 2019. The index uses the

perceptions of experts and businesspeople to provide a measure of the level of

public sector corruption in a nation. The measure is provided in the form of a

score, with 100 representing the absence of corruption, and 0 representing a

high level of corruption. In the 2019 release, Australia ranked 12th in the

world out of 180 nations, with a score of 77. This is a one rank increase

from the previous year, maintaining the same score of 77.

Figure 4: Corruption Perceptions Index 2019

Source: Transparency International, Corruption

Perceptions Index 2019 (download

‘Maps’), accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The Corruption Perceptions Index measures the

perceived level of public sector corruption. Transparency International obtains

data from 13 data sources which measure public sector corruption—the

Economist Intelligence Unit’s Country Risk Service, for

example—with each source fulfilling a set of requirements to be considered.

The requirements include reliable and valid methodology, the rating of a

substantial number of countries, and the credibility of the source. Sources are

then standardised on a scale of 0-100, with the average being used as a

nation’s score. Standardisation is achieved through the subtraction of

the mean of each source in a set baseline year from each country score, which

is then divided by the standard deviation from the baseline year. Following

this, standardised scores are transformed to a 0-100 scale through the

multiplication of the score by the CPI standard deviation in 2012, and the

addition of the mean from the 2012 CPI. Transparency International also

provides a measure of uncertainty in their reporting, in the form of standard

errors and confidence intervals associated with each score.

Commentary

Similar to other indexes, the main criticism of the Corruption

Perceptions Index is that it is based on subjective rankings. It is

important to note, however, that these rankings are based on expert, rather

than analyst, views. The measure has also come under criticism for not being a

good measure of actual corruption, as Xypolia notes in The

Conversation: ‘What these indexes have in common is

that they are all largely based on surveys about perceptions on corruption

– personal judgements, not hard data’:

... One of the reasons why we rely on these

indexes is because we have struggled to come up with anything better.

Corruption by its very nature usually takes place away from the public eye and

records, which makes it difficult to measure.

5. Education

Programme for International Student

Assessment

The OECD Programme

for International Student Assessment (PISA) undertakes testing

of 15 year old students in three areas: reading, mathematics, and science. The

test is undertaken every three years, with the most recent results released in

2018. Students were assessed in 79 countries and economies, with a

particular focus on OECD countries. In the 2018 results, Australian students

received a mean reading score of 503, statistically significantly above the

OECD average of 487, but far below the 555 score achieved by mainland China. In

mathematics, Australia scored only slightly above the OECD average, scoring 491

points against the average of 489. This ranks below most comparator

countries such as New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom, but above the

United States. The highest score for mathematics was China, who scored 591

points. In science, Australia received 503 points, relative to the OECD

average of 489 points. China received the highest score of 590 points. While consistently

above the OECD average, the rankings do show that Australia has room for

improvement, regularly featuring below many countries of cultural comparison.

Relative to 2015, Australia’s scores in the science and mathematics

categories have decreased, as have OECD averaged; while Australia has

maintained the same reading score with a slight decrease in OECD average.

What does it measure?

PISA seeks to test students on their proficiency across the

areas of reading, mathematics and science. To do so, a test framework is

developed. In developing the framework, international experts from each area

are enlisted to develop their respective area, with the framework agreed upon

by countries. Students are sampled from a population of 15 year olds within a

country. Questions within a test range from low to high difficulty, with

proficiency within a subject determined by an ability to answer questions successfully.

PISA scores are set relative to the variation in results on a normal

distribution, with mean scores around 500 points, and standard deviations

around 100 points. As such, a score of 490 in one year does not necessarily

reflect the same as a score of 490 in another year.

Commentary

The core advantage of PISA is that is tests students on

their ability to complete practical tasks. Unlike other indexes of education

which rely on years in schooling or population completion rates of schooling,

PISA provides a snapshot of one of the key goals of an education system: the

development of students’ abilities to develop comprehension and problem

solving skills across a number of subjects. With that said, however, there are

aspects of education which PISA does not capture. Another of the core goals of

an education system is to provide students with the ability to succeed as part

of the labour force. Without incorporation of measures such as completion

rates, and rates assessing transitions to work, PISA fails to capture some core

components of education. Furthermore, the variability of scores across time

limits the comparability of countries performance across years, instead meaning

comparisons must be drawn on performance relative to other countries year on

year. For other measures which incorporate a broader range of indicators, see

the OECD’s

Better Life Index Education section, or the UNDP

Education Index (p. 54).

6. Environment

Environmental Performance Index

The Environmental

Performance Index (EPI) is a joint project of the Yale Center for

Environmental Law & Policy, and the Center for International Earth Science

Information Network at Columbia University. The EPI was most recently released in 2020.

It assessed 180 countries, with rankings constructed on two core categories—environmental

health and ecosystem vitality—comprised of 32 indicators. Australia

ranks 13 with a score of 74.9, receiving the 11th highest score for

environmental health of 91.6, but a middling score for ecosystem vitality of

63.8. This is a 5.5 point improvement across 10 years.

Table 1: 2019 Environmental Performance Index Rankings

| Rank |

Country |

EPI

Score |

10-Year

Change |

| 1 |

Denmark |

82.5 |

7.3 |

| 2 |

Luxembourg |

82.3 |

11.6 |

| 3 |

Switzerland |

81.5 |

8.6 |

| 4 |

United Kingdom |

81.3 |

9.0 |

| 5 |

France |

80.0 |

5.8 |

| 6 |

Austria |

79.6 |

5.4 |

| 7 |

Finland |

78.9 |

6.0 |

| 8 |

Sweden |

78.7 |

5.3 |

| 9 |

Norway |

77.7 |

7.6 |

| 10 |

Germany |

77.2 |

1.2 |

| 11 |

Netherlands |

75.3 |

1.5 |

| 12 |

Japan |

75.1 |

-0.5 |

| 13 |

Australia |

74.9 |

5.5 |

Source: Environmental Performance Index, 2020 Environmental

Performance Index, accessed 16 November 2020.

What does it measure?

The EPI is influenced by two policy objectives:

environmental health, which seeks to measure environmental threats to human

health, such as poor air quality; and ecosystem vitality, a measure of a

country’s natural resources and ecosystem, such as biodiversity and

forests. Each of the policy objectives is informed by a number of categories,

with each category informed by indicators. The EPI is a hierarchical model,

with weighting occurring at each stage to inform the next step. Indicators are

normalised on a 0-100 scale for consistency. The weights are informed through

objective and subjective means: for environmental health, weights are assigned

based on the distribution of disability-adjusted life-years, or DALYs, lost to

environmental health influences; whereas for ecosystem vitality, weights are

subjective, informed by previous literature in the area. The overall indicator

is weighted 40 per cent in environmental health, and 60 per cent in ecosystem

vitality.

Commentary

The EPI represents a comprehensive measurement of

environmental health and performance within countries, accounting for a broad set

of environmental indicators. There is, however, a notable omission of policy

considerations from the metrics: the framework does not engage with areas such

as broader environmental policies related to climate change or clean energy.

The EPI is complemented by other indexes which focus on specific areas, such as

the Climate Change Performance Index

and the Global

Adaptation Index.

7. Health

Global Health Security Index

The Global Health

Security Index, or GHS Index, is a joint project of the Nuclear Threat

Initiative and the John Hopkins Center for Health Security, developed by the

Economist Intelligence Unit. The GHS Index measures health security and associated

health response capabilities, with the first index released in 2019. The

measure is applied to 195 countries. The index is developed with a focus on six

health security and response categories: prevention, detection and reporting,

rapid response, health system, compliance with international norms, and risk

environment. In the 2019 index, Australia ranked 4th, with an index

score of 75.5.

Table 2: 2019 Global Health Security Index Results

| Rank |

Country |

Index

Score |

Region |

Population |

Income |

| 1 |

United States |

83.5 |

Northern America |

100m+ |

High income |

| 2 |

United Kingdom |

77.9 |

Europe |

50-100m |

High income |

| 3 |

Netherlands |

75.6 |

Europe |

10-50m |

High income |

| 4 |

Australia |

75.5 |

Oceania |

10-50m |

High income |

| 5 |

Canada |

75.3 |

Northern America |

10-50m |

High income |

| 6 |

Thailand |

73.2 |

Southeastern Asia |

50-100m |

Upper middle income |

| 7 |

Sweden |

72.1 |

Europe |

1-10m |

High income |

| 8 |

Denmark |

70.4 |

Europe |

1-10m |

High income |

| 9 |

South Korea |

70.2 |

Eastern Asia |

50-100m |

High income |

| 10 |

Finland |

68.7 |

Europe |

1-10m |

High income |

Source: Global Health Security Index, Country Ranking View of Index Results,

2019, accessed 16 November 2020.

What does it measure?

The GHS seeks to measure a country’s preparedness for

a mass health event, such as a pandemic. It is comprised of indicators across

six categories, with a focus on prevention of pathogens, a detection of and

quick response to such pathogens, and the ability of a health system in dealing

with such events. All data is obtained from open-source information, such has

country-reported data, or that reported by international bodies, like the World

Health Organization. The index is comprised of 34 indicators, which in turn are

made up of 85 subindicators. For example, the ‘prevent’ category is

comprised of six indicators, one of which is biosafety. Biosafety is scored

according to two subindicators: whole-of-government biosafety systems; and

biosafety training and practices. The overall index score is obtained by

averaging the six category scores, with each category weighted equally.

Commentary

Given the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, the GHS proved

correct in noting that discussion and preparedness for such events was

necessary. The index has, however, proven to be inaccurate in its assessments

of country capabilities when contrasted with evidence that has arisen from the

pandemic. Abbey

et al., for example, compare GHS rankings of OECD countries with an assessment

of their performance throughout the pandemic. Of the five highest ranked OECD

countries in the GHS, only Australia has performed well, ranking second in the

authors’ multi-criteria rank. Alternatively, out of the 36 OECD countries

assessed, the top three countries in the GHS—the United States, United

Kingdom, and Netherlands—rank 32nd, 35th and 36th, respectively. Abbey et

al. posit that a possible explanation for over- and under-performing countries

in the pandemic has been the role of political leadership, a variable

unassessed in the GHS. While the GHS has correctly identified a requirement for

increased health security awareness, the recent pandemic has highlighted a need

for the index to assess their inputs. There are few health indexes available,

but the World Health Organization

publish a wide range of health statistics useful for identifying a

country’s performance in a number of areas.

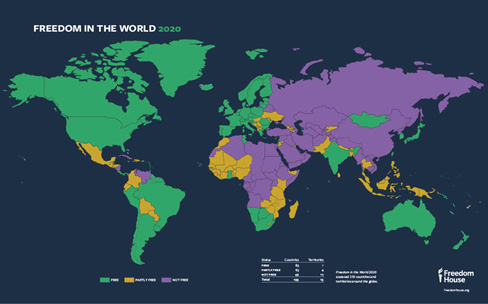

8. Human Rights

Freedom in the World Index

The Freedom House Freedom

in the World report provides a numerical rating of freedom, based on

political rights and civil liberties. Countries are assigned a ranking out of

100, with 0 being not at all free, and 100 being fully free. Freedoms are assessed

on the basis of two subcategories relating to political rights and civil

liberties. In the most recent report, released in 2020, Australia achieved a

score of 97, ranking

jointly at 8th in the world, tied with Denmark, Ireland and New Zealand.

Over the past 10 years, Australia has increased in score from 96 to 97. The

three areas in which Australia’s

ranking did not score highly were all related to civil liberties: scoring 3

out of 4 points for freedom and independence of the media; 3 out of 4 points

for the equal treatment of the population under the law, policies and practice;

and 3 out of 4 points for freedom and opportunity from economic exploitation.

On the final two points, Indigenous peoples are noted as falling behind the

rest of the population.

Figure 5: Freedom in the World 2020

Source: Freedom House, Freedom

in the World 2020, p. 7, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The overall measure is a score based on two categories:

political rights; and civil liberties. Each category is further addressed at

several sublevels. Using 25 measures (each scoring out of 4), political rights

are assessed based on electoral process, political pluralism and participation,

and the functioning of government; civil liberties are assessed based on

freedom of expression and belief, associational and organisational rights, rule

of law, and personal autonomy and individual rights. Each sublevel is also

provided with guiding questions to assist analysts with ratings. Due to its

broad scope, the Freedom in the World Index incorporates a number of relevant

freedoms in its measure. Most notable of these is freedom of the media,

included as a measure of civil liberty.

Commentary

Critiques of Freedom House’s Index and other human

rights indexes relate to the fact that, although there may be methodological

guidelines, ratings are still largely

subjective. Furthermore, since the ratings consider a broad overview of

freedom, human rights records might not be fully considered. For example, in

2017 the United Nations released

a statement criticising Australia’s human rights performances in

various areas, namely treatment of refugees and indigenous rights. These

criticisms are not necessarily reflected in the Index.

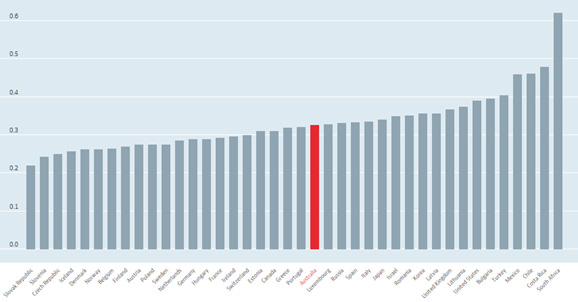

9. Inequality

OECD Income Inequality

A traditional economic measure for income inequality is the

Gini coefficient. The OECD publishes calculations of the income Gini

coefficient for all OECD countries. The OECD’s Income

inequality measure reports Australia had a Gini coefficient of 0.33 in 2019,

where 1 denotes complete inequality and 0 denotes complete equality. This is

higher than the median coefficient in the OECD, with Australia having the 14th

highest coefficient of the 35 measured OECD countries. Income distribution

in Australia is more equal than 13 other OECD countries.

Figure 6: OECD Income Inequality

Source: OECD Data, Income inequality,

2019, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

In order to calculate income inequality, we must first

provide a definition of income. The OECD defines

a household’s disposable income as earnings, self-employment and capital

income plus public cash transfers, with income taxes and social security

contributions deducted. The income of a household is attributed

to each of its members, with an adjustment to reflect differences in needs for

households of different sizes. The Gini coefficient is based on the comparison

of cumulative proportions of the population against cumulative proportions of

income they receive, and it ranges between 0 in the case of perfect equality

and 1 in the case of perfect inequality.

Commentary

In comparison to the OECD

average, Australia has a relatively high level of income inequality—22 of

35 countries have lower measures of income inequality. However, in comparison

with countries that share similarities with Australia’s cultural and

political framework (including Canada, the United Kingdom and the United

States), Australia maintains more income equality. Of those countries, only

Canada has a lower score for income inequality, with a Gini coefficient of

0.307. The World Economic Forum provides an extensive analysis of gender

inequality in its The Global

Gender Gap Report 2020, in which Australia ranks 44th out of 153

countries.

10. Innovation, science &

technology

Global Innovation Index

The Global

Innovation Index, a joint project by Cornell University, INSEAD and the

World Intellectual Property Organization, provides a measure of innovation

within nations using a combination of data across seven areas: institutions;

human capital and research; infrastructure; market sophistication; business

sophistication; knowledge and technology outputs; and creative outputs. Also

included in the rankings are innovation input and output sub-indexes, which are

used to calculate the Global Innovation Index, and the efficiency ratio

of the country. In the 2020 report, which covered 131 economies, Australia

ranked 23rd in the Global Innovation Index, a decrease of one spot

from the previous year. Australia performed best in the category of market

sophistication, ranking 7th in the world, but was dragged down by a ranking of

40th in the category of knowledge and technology outputs.

What

does it measure?

The Global Innovation Index is measured across seven

areas. Each section has three different subsections, each comprising a set of

indicators. For example, the institutions pillar is comprised of the three

subsections of political environment, regulatory environment, and business

environment. The political environment subsection is comprised of two

indicators: political and operational stability, obtained through the IHS Markit

Country Risk scores; and government effectiveness, obtained through the

World Bank’s Worldwide

Governance Indicators. Subsection scores are calculated as a weighted

average of the relevant indicators, with section scores being calculated as a

weighted average of the relevant subsections. As such, the Global Innovation

Index includes a wide array of data and indicators, leading to a broad

interpretation of innovation. For example, while factors such as education and

infrastructure may directly influence innovation, underlying factors such as

political stability are also influential in the institutional structure of innovation.

The index is largely comprised of data-based indicators. Of the 80 indicators,

58 are drawn from hard data, 18 from indexes, and just 4 are formed in

qualitative ways, through surveys of experts.

Commentary

The Global Innovation Index provides an extensive

measure of innovation. The indicators used for the index are largely

quantitative, with only five of the 80 indicators based on qualitative data.

This leads to a robust index, as the limited qualitative inputs allows for a

more impartial index. While the index provides a wide-ranging measure of

innovation, incorporating factors such as education, science and technology,

other indexes may be more useful when looking for a specific measure of each of

those factors.

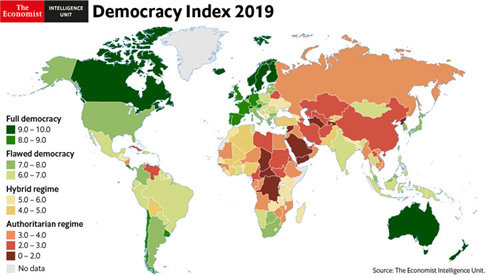

11. Politics and democracy

Democracy Index

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index uses

various indicators to assess the quality of democracy in 167 countries. The

index is based on 60 indicators across five categories: electoral process and

pluralism; the functioning of government; political participation; political

culture; and civil liberties. The most recent ratings for 2019 were released in

2020. Australia received a score of 9.09 out of 10, ranking it 9th. Australia’s

score of 9.09 has remained stable over time, with a score of 9.09 in 2006,

dropping as low as 9.01 from 2014-2016, before rising back to 9.09 from 2017.

Figure 7: Democracy Index 2019

Source: Global Democracy Ranking, Democracy Index 2019,

accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

Each of the five categories has a rating on a 0 to 10 scale;

the overall index is the simple average of the five category indexes. The

category indexes are based on the sum of the indicator scores in the category.

Examples of indicators include: freedom to form political parties; the

pervasiveness of corruption; the percentage of women in parliament; perceptions

of military rule; and freedom to form professional organisations and trade

unions. Adjustments to category scores are made if countries do not score a 1

in the following critical areas of democracy: whether national elections are

free and fair; the security of voters; the influence of foreign powers on

government and the capability of the civil service to implement policies. In

addition to experts’ assessments, the EIU uses, where available, public

opinion surveys—particularly in the political participation and political

culture categories. Index values are used to place countries within one of four

types of regime: full democracies; flawed democracies; hybrid regimes; and

authoritarian regimes.

Commentary

In order to limit subjective responses, the Democracy Index

combines expert assessments with public opinion data. Alternative measures, for

example that published by Freedom House (see index 8. Human Rights), use

only qualitative assessments to assign scores to countries. However, the

inclusion of dichotomous values (which take the value of 0, 0.5 or 1) in the

Democracy Index, removes some of the nuance achieved in other measures. For

example, the indicator ‘public confidence in parties’ takes on a

value of 1, if more than 40 per cent have confidence; 0.5 if it lies between 25

and 40 per cent; and 0 if less than 25 per cent.

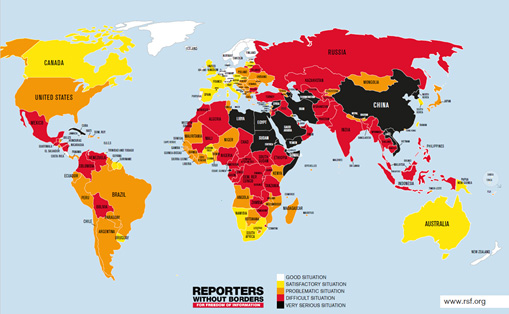

12. Press freedom and the rule of law

World Press Freedom Index

The World Press Freedom

Index is published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF). The

degree of freedom available to journalists in 180 countries is determined by

pooling the responses of experts to a questionnaire

(with 87 questions) devised by RSF. This qualitative analysis is combined with

quantitative data on abuses and acts of violence against journalists during the

period evaluated. The criteria evaluated in the questionnaire are pluralism,

media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative

framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports

the production of news and information. These are combined with data on abuses

and violence against journalists and media outlets. Countries are given scores

ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best possible score and 100 the worst.

In the 2020 rankings, Australia ranked 26th with a score of 20.21, a

fall of five places since 2019.

Figure 8: World Press Freedom Index

Source: Reporters Without Borders, 2020 World Press Freedom Index, accessed

16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The RSF calculates two scores. The first, ScoA is based on

the first six of the seven indicators listed above; the second, ScoB, combines

the first six measures with the seventh (abuses). (The abuses

indicator for each country is calculated on the basis of the data about the

intensity of abuses and violence against media actors during the period

evaluated.) A country’s final score is the greater of these two

scores. The method prevents an inappropriately low score (high ranking) being

given to a country where few or no acts of violence against journalists take

place because the provision of news and information is tightly controlled.

Commentary

The use of two measures provides a useful way to compare

press freedom across countries with very different journalism industries. In

some nations, particularly those with a tightly controlled, government-directed

industry, explicit abuses may be minimal. For example, the second lowest ranked

country in the index, Turkmenistan, has 0 abuses listed. However, its poor results

in ScoA results in a worse ranking. On the other hand, a country such as

Afghanistan has, relative to other countries in the region, a low score when it

comes to ScoA, but due to a high measure of abuses scores much higher in the

second measure, leaving it with a ranking of 122. With zero abuses, for

example, Afghanistan would have ranked 94th.

13. Renewable energy

Renewable Energy Country

Attractiveness Index

The Renewable

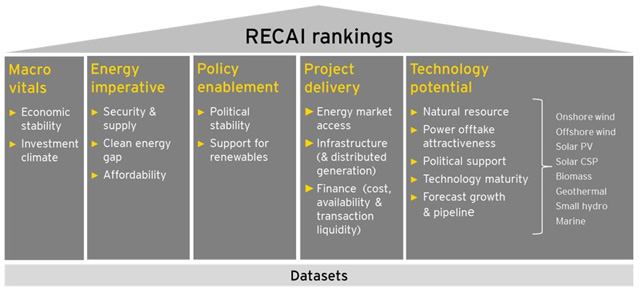

Energy Country Attractiveness Index (RECAI) is

developed by EY, with the most recent rankings published in May 2020. RECAI

ranks the top 40 countries in the world on the attractiveness of their

renewable energy investment and deployment opportunities. It assesses five

domains: macro vitals; energy imperative; policy enablement; project delivery;

and technology potential. Australia ranks well relative to other countries,

placing 4th behind the United States, China and France, but ahead of

Germany and the United Kingdom.

Table 3: 2020 Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index

| Rank |

Country |

Change

from

2016 |

| 1 |

United States |

0 |

| 2 |

China |

0 |

| 3 |

France |

5 |

| 4 |

Australia |

6 |

| 5 |

Germany |

0 |

| 6 |

United Kingdom |

7 |

| 7 |

India |

-4 |

| 8 |

Denmark |

7 |

| 9 |

Netherlands |

8 |

| 10 |

Japan |

2 |

Source: EY, Renewable

Energy Country Attractiveness Index May 2020 and Renewable

Energy Country Attractiveness Index May 2016, accessed 16 November 2020.

What does it measure?

The RECAI rankings factor various parameters from five

groups relevant to the renewable energy industry. All parameters are shown in

Figure 10 below.

Figure 9: Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index—Methodology

Source: EY, RECAI

Methodology, EY Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness index, 2019,

accessed 16 November 2020.

Each of the five pillars is assessed based on a set of

parameters. Each parameter is assessed through a series of datasets, with each

dataset converted to a range from 1-5. Parameter scores are then weighted based

on these scores. The various factors were chosen according to their role in

increasing the market attractiveness of renewable energies. This includes

economic, political and technological factors, as technological inputs are of

limited effectiveness if there is not a stable and supportive government, or a

stable economy, enabling the exploitation of their full potential.

Commentary

The RECAI provides a measure of the availability and

progression of renewable energies across 40 countries. Other indexes—such

as the World Bank’s measures of Energy and Mining—are

more useful when assessing energy output and composition as a whole. One such

measure is fossil fuel and renewable energy as a percentage of total final

consumption.

14. Security and safety

Safe Cities Index

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU’s) Safe Cities

Index (SCI) assesses urban security using 57 indicators across 60 cities.

The index—measured on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 representing

‘best health’—uses four broad pillars: digital security;

health security; infrastructure security; and personal security. The most

recent iteration of the SCI was released in 2019, with two Australian cities

being assessed: Sydney was ranked 5th with a score of 87.9; Melbourne

was ranked 10th with a score of 87.3.

Table 4: 2019 Safe Cities Index Rankings

| Rank |

City |

Score |

2017 score |

| 1 |

Tokyo |

92.0 |

89.8 |

| 2 |

Singapore |

91.5 |

89.6 |

| 3 |

Osaka |

90.9 |

88.9 |

| 4 |

Amsterdam |

88.0 |

87.3 |

| 5 |

Sydney |

87.9 |

86.7 |

| 6 |

Toronto |

87.8 |

87.4 |

| 7 |

Washington, DC |

87.6 |

80.4 |

| =8 |

Copenhagen |

87.4 |

N/A |

| =8 |

Seoul |

87.4 |

83.6 |

| 10 |

Melbourne |

87.3 |

87.3 |

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, Safe

Cities Index 2019, p. 15, accessed 16 November 2020 and Economist

Intelligence Unit, Safe

Cities Index 2017, p. 5, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

As noted above, the SCI is comprised of four, equally

weighted pillars. There are 57 indicators: 17 quantitative; and 40 qualitative.

Every city is scored across input and output performance within and across the

four domains. Each domain comprises between eight and 21 indicators, divided

between inputs (capacity/preparedness-driven), such as policy measures and

access to services, and outputs (performance-driven), such as air quality and

the prevalence of crime. Digital security assesses the ability of urban

citizens to freely use the internet and other digital channels without fear of

privacy violations or identity theft. Health security measures how

cities fare in terms of environmental policy as well as the level and quality

of healthcare available to residents. Infrastructure security considers

the built physical environment, such as city infrastructure and its

vulnerability to disasters and terrorist attacks. Personal security

considers how at-risk citizens are from crime, violence, man-made threats and

natural disasters.

Commentary

The SCI presents a measure of safety within a city,

assessing various elements that contribute to security. By comparison, in the

OECD’s Better

Life Index, Australia ranks 27th out of 40 in safety. Although having a

rate of homicide well below the OECD average, only 63 per cent feel safe

walking home at night (below the OECD average). The contrast between the two

indexes presents an interesting divergence in the assessment of safety in

Australia.

15. Tourism

The Travel & Tourism

Competitiveness Index

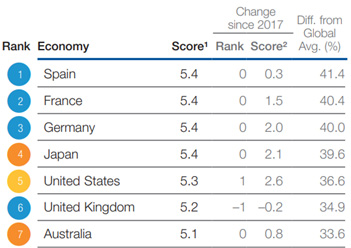

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF’s) Travel

& Tourism Competitiveness Report presents the Travel & Tourism

Competitiveness Index (TTCI) which, published biennially, benchmarks the travel

and tourism competitiveness of 140 economies and measures the ‘set of

factors and policies that enable the sustainable development of the Travel

& Tourism (T&T) sector, which in turn, contributes to the development

and competitiveness of a country’.

The index is comprised of four subindexes: the enabling

environment; travel and tourism policy and enabling conditions; infrastructure;

and natural and cultural resources. Each subindex includes a number of pillars.

In total, there are 14 pillars and 90 individual indicators, distributed among

the different pillars. Countries are assigned a score between 1 and 7 based on

how they perform, with better performing countries achieving higher scores. In

the 2019 release of the TTCI, Australia was ranked 7th with a score of

5.1. Spain, France, Germany, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom

received higher scores.

Figure 10: 2019 Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index—Rankings

Source: World Economic Forum, ‘Travel

& Tourism Competitiveness Report’, 2019, p. xiii, accessed 16

November 2020.

What

does it measure?

Each of the four subindexes is made up of a number of

pillars. Subindexes and pillars are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11: Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index - Methodology

Source: World Economic Forum, ‘Travel

& Tourism Competitiveness Report’, 2019, p. ix, accessed 16 November

2020.

Each pillar is compiled of various indicators, with scores

for the pillars calculated as an unweighted average of these indicators. For

example, the enabling environment subindex is comprised of 12 business

environment indicators, five safety and security indicators, six health and

hygiene indicators, nine human resources and labour market indicators and eight

ICT readiness indicators. Each subindex score is calculated as the average of

the contributing pillars. Likewise, the total score for the TTCI is calculated

as the average of the subindexes.

Two thirds of the dataset for the TCCI is statistical data

from international organisations. The remaining third is based on survey data

from the WEF’s annual Executive Opinion Survey, which is used to measure

qualitative concepts.

Commentary

The 2019 Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report

finds that travel and tourism competitiveness continues to improve worldwide,

but also flags that future demand for transportation services, especially

aviation, might outpace improvements in infrastructure capacity.

Analysis of TTCI subindexes can help to identify areas for

improvement. For example, while Australia appears to rank well across the

board, improvements could be made if we look at the travel and tourism policy

and enabling conditions, where Australia ranks a joint 28th. Australia’s

environmental sustainability—measured using policy indicators such as the

stringency and enforcement of government’s environmental regulations, and

variables assessing the status of water, forest resources and marine

life—ranks 49th, alongside Romania and Tanzania.

16. Well-being and happiness

World Happiness Report

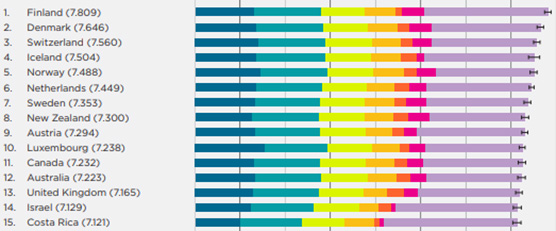

The most recent World Happiness Report was

released in 2020. The report indicates that Australia ranks relatively well in

terms of happiness—measured across six variables—ranking 12th

out of 153 countries. Compared to the 2016 report, this is a drop of 3

ranks from 9, with a reduction in score from 7.313 to 7.223.

Figure 12: 2020 World Happiness Rankings

Notes: Dystopia is a hypothetical country with ‘values

equal to the world’s lowest national averages’ (p. 16). Residual ‘simply

represents that part of the national average ladder score that is not explained

by our model’ (p. 18).

Source: J Helliwell et

al. (eds), World Happiness Report 2020,

p. 19, accessed 16 November 2020.

What

does it measure?

The 2020 update presents average life evaluation scores for

153 countries. These scores are based on subjective responses to the Cantril

ladder question: participants are asked to imagine their position in a ladder

from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the best possible life, and 0 the worst

possible.

The authors consider six key variables:

- GDP per capita

- healthy years of life expectancy

- social support (as measured by having someone to count on in

times of trouble)

- trust (as measured by a perceived absence of corruption in

government and business)

- perceived freedom to make life decisions

- generosity (as measured by recent donations).

Furthermore, the 2020 report focuses on the influences

of environments on happiness, in particular the effects of social, urban and

natural environments.

Commentary

The notion of gauging the development of a nation based on

individual, self-reported life evaluation measures has been criticised, with some

debating ‘whether subjective views are truly measurable’ (p. 266).

However, the OECD report How’s

Life: Measuring Well-Being states ‘a large body of recent

research has shown … that it is indeed possible to make valid comparisons

between different groups of people’ (p. 266). It further states:

Measures of life satisfaction are a useful complement to more

traditional indicators based on objective conditions because they present an

overall picture of well-being that is grounded in people’s preferences

rather than in a-priori judgements about what are the important drivers of

individuals’ well-being. (p. 266)

The authors acknowledge a range of statistical and

analytical limitations, such as the risk that the explanatory ‘variables

[they] use may be taking credit properly due to other variables, or to unmeasurable

factors’ (p. 18). Nevertheless, in the 2016 report, the authors

argue:

that happiness, as measured by life evaluations, provides a

broader indicator of human welfare than do measures of income, poverty, health,

education, and good government viewed separately. We now make a parallel

suggestion for measuring and addressing inequality. Thus we argue that

inequality of well-being provides a better measure of the distribution of

welfare than is provided by income and wealth … (p. 4)

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.