29

June 2020

PDF version [1496KB]

Dr Damon

Muller

Politics and Public

Administration

Executive

summary

- This paper provides an overview of the 2019 federal election,

including the results, the political environment, and the major features of the

campaign.

- The 2019 federal election was held on Saturday 18 May 2019.

- The Liberal-National Coalition, led by Prime Minister Scott

Morrison, won a majority in the House of Representatives with 77 of the 151

seats and 51.5 per cent of the national two-party preferred vote, a net

increase of one seat on the 2016 election result.

- The Australian Labor Party won 68 seats, with the Australian Greens

retaining their single seat. Three independents were elected to the House of

Representatives (including Helen Haines, who replaced retiring independent

Cathy McGowan in the division of Indi), along with one Centre Alliance MP and

one Katter’s Australian Party MP.

- The Coalition won 19 seats in the Senate, with the ALP winning 13,

the Greens winning six, and the Jacqui Lambie Network and Pauline Hanson’s One

Nation winning one seat each. When combined with the ongoing senators, the

Coalition has 35 votes in the Senate, Labor 26, the Greens nine and there are

six other cross-benchers.

- Mr Morrison was elected as Liberal Party leader and Prime

Minister on 24 August 2018 following the ousting of Malcolm Turnbull. The

Nationals also contested the election with new leader and Deputy Prime Minister

Michael McCormack, who replaced former leader Barnaby Joyce in February 2018.

- The election followed the ‘citizenship crisis’ of the 45th

Parliament in which 15 senators and members of the House of Representatives

were disqualified or resigned from Parliament. Election candidates were

required to complete a qualification checklist with their nomination, and only

one citizenship case was referred to the High Court following the election,

which was dismissed by the Court.

- The Coalition won the election having trailed Labor in the polls

for essentially the entire term of the 45th Parliament, representing an

unprecedented failure of polling for Australian federal elections. The polling

failure has resulted in at least one inquiry and may lead to changes in the

performance and transparency of Australian polling.

- Clive Palmer, who contested the 2013 federal election with the

Palmer United Party, returned to electoral politics with the renamed United

Australia Party. While the party failed to win any seats, the estimated $60

million advertising spend by the party eclipsed the spending of all other major

parties, and has led to some calling for expenditure caps in federal elections.

Contents

Executive summary

Introduction

Results

Timing of the election

Redistributions

The election campaign

The opinion polling failure

Cost of the election and campaign

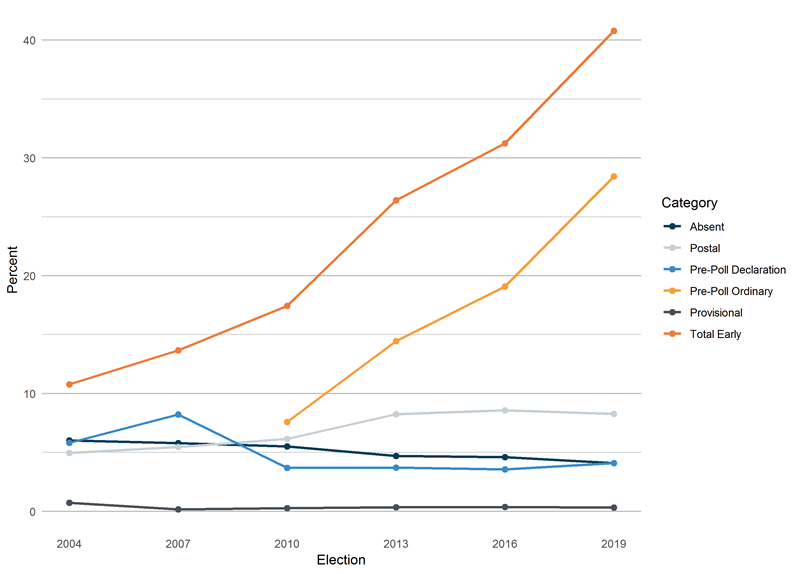

Early voting

Electoral participation

Conclusion

Appendix A: Parties contesting the

2019 federal election

Appendix B: Section 44 disqualifications

Appendix C: Final opinion poll results

prior to the 2019 federal election

Appendix D: Public election funding

paid

Introduction

This paper provides an overview of the 2019 federal election.

This includes the political and electoral context in which the election

occurred, the results in the House of Representatives and the Senate, the

timing of the election and the election campaign. The paper also discusses key

democratic indicators such as early voting, campaign spending, and electoral

participation.

Held on Saturday 18 May 2019, the 2019 federal election

returned Prime Minister Scott Morrison (Cook, NSW) and the Liberal-National

Coalition to government with a majority of 77 of the 151 seats in the House of

Representatives. The result meant that Mr Morrison was the third Liberal Prime

Minister since the 2013 federal election when Tony Abbott won government from a

minority Labor Government. The Coalition was widely expected to lose the 2019 election,

having trailed the Labor Opposition, led by Bill Shorten (Maribyrnong, Vic.), in

the polls for almost the entire parliamentary term.

The

electoral context

While every election is unique in some respects, the 2019

federal election came after a particularly turbulent term that followed the

2016 double dissolution election. After emerging from the 2016 federal election

with a slim majority of 76 seats, the Coalition lost a number of its MPs and senators

due to ineligibility (as did Labor), a prime minister due to internal

instability, and its majority in the House before the 2019 federal election.

Parliament’s

citizenship crisis

On 14 July 2017 Greens Senator Scott Ludlam (WA) announced

by tweet that he was resigning from the Senate after he was revealed to have

been a New Zealand citizen.[1]

Section 44(i) of the Australian Constitution holds that anyone holding

citizenship of another country is incapable of being chosen or sitting as a

senator or member of the House of Representatives.

Senator Ludlam’s resignation was particularly notable as it

led to widespread citizenship examinations that eventually resulted in a total

of 15 disqualifications due to section 44(i)—seven from the House of

Representatives and eight from the Senate. A full list of the disqualified

members and senators is in Appendix B.

While Senator Ludlam was the first of the section 44(i) citizenship

casualties, he was the third senator to have been found ineligible in the 45th

Parliament under section 44. The High Court finding former Pauline Hanson’s One

Nation (PHON) senator Rodney Culleton (WA) ineligible in February 2017 due to

having been convicted and under sentence for a crime (section 44(ii)),[2]

and in April 2017 the Court finding Family First Senator Bob Day (SA) ineligible

under section 44(v) due to a direct or indirect pecuniary interest with the

public service of the Commonwealth.[3]

While most of the members of the House of Representatives

who were disqualified or resigned prior to being disqualified were returned at subsequent

by-elections, the recounts required by the High Court in the Senate led to

considerable change in the composition of the Senate. This resulted in changes

in the party composition as replacements were either elected from a different

party (Nationals Senator Fiona Nash was replaced by Liberal Jim Molan in NSW)

or left the party for which they ran at the 2016 election.[4]

As such the Senate, which elected all of its 76 senators at the 2016 double

dissolution election, looked quite different immediately before the 2019

federal election.

As a response to the citizenship crisis, the Parliament

passed the Electoral

Legislation Amendment (Modernisation and Other Measures) Act 2018 in

February 2019. One effect of this legislation was to require candidates

nominating for election to the House of Representatives or the Senate to

complete a candidate qualification checklist as part of their nomination

process. The checklist requires candidates to list information about their

citizenship and family history, and for the 2019 election completed checklists

were made available on the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) website. No

successful citizenship challenges following the election suggest that the

initiative was successful in obliging candidates to consider their citizenship

prior to nominating.

Leadership

change and the minority government

Scott Morrison led the Liberal Party (LP) to the election,

having taken over as Liberal leader and Prime Minister in August 2018 following

the ousting of Malcolm Turnbull (Wentworth, NSW) less than nine months before

the election. Prior to the leadership change, Kevin Hogan MP (NP, Page, NSW) had

indicated that if there was a leadership spill he would move to the crossbench

in protest—a move he duly made.[5]

Mr Turnbull subsequently resigned from the Parliament,

triggering a by-election in his seat of Wentworth on 20 October 2018. The

seat was narrowly won by independent Dr Kerryn Phelps. Following the loss of

Wentworth, the Coalition was reduced to 74 seats of the 150 seat House of

Representatives, two seats short of an absolute majority of 76 votes. While an

absolute majority is only required in a small number of situations, the Speaker

of the House (one of the Coalition’s 74 members) does not vote except to have a

casting vote in the case of a tie.[6]

Coalition numbers were reduced further when, on 27 November

2018, Liberal Julia Banks (Chisholm, Vic.) announced that she was leaving the LP

due to disillusionment with the party and would sit as an Independent.[7] As a result of

these various developments, despite winning 76 seats at the 2016 federal

election, the Coalition went into 2019 as a minority government (even before some

of the electoral redistributions, which are discussed below).

The election was also the first for Michael McCormack (Riverina,

NSW) as leader of the Nationals (NP); Mr McCormack had taken over as leader in

February 2018 from Barnaby Joyce (New England, NSW). Mr Joyce had resigned as NP

leader and deputy Prime Minister following weeks of controversy over his

personal life.[8]

Results

House of

Representatives

The Liberal-National Coalition was returned to government at

the May 2019 election with 51.53 per cent of the two-party preferred vote. The

Coalition had a net gain of one seat compared to the 2016 federal election,

winning a total of 77 seats in the 151 seat House of Representatives (a

majority of one seat following the appointment of a Liberal Speaker). Labor won

68 seats (a net loss of one), with three seats going to independents, one to

the Greens, one to the Centre Alliance (CA) (formerly the Nick Xenophon Team)

and one to Katter’s Australian Party (KAP) (Table 1 below).

Table 1: House of

Representatives seats won by party by state, 2019 federal election

| State |

ALP |

LP |

LNP |

NP |

GRN |

IND |

KAP |

CA |

Total |

| NSW |

24 |

15 |

- |

7 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

47 |

| VIC |

21 |

12 |

- |

3 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

38 |

| QLD |

6 |

- |

23 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

30 |

| WA |

5 |

11 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

16 |

| SA |

5 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

10 |

| TAS |

2 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

5 |

| ACT |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

| NT |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

| Total |

68 |

44 |

23 |

10 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

151 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

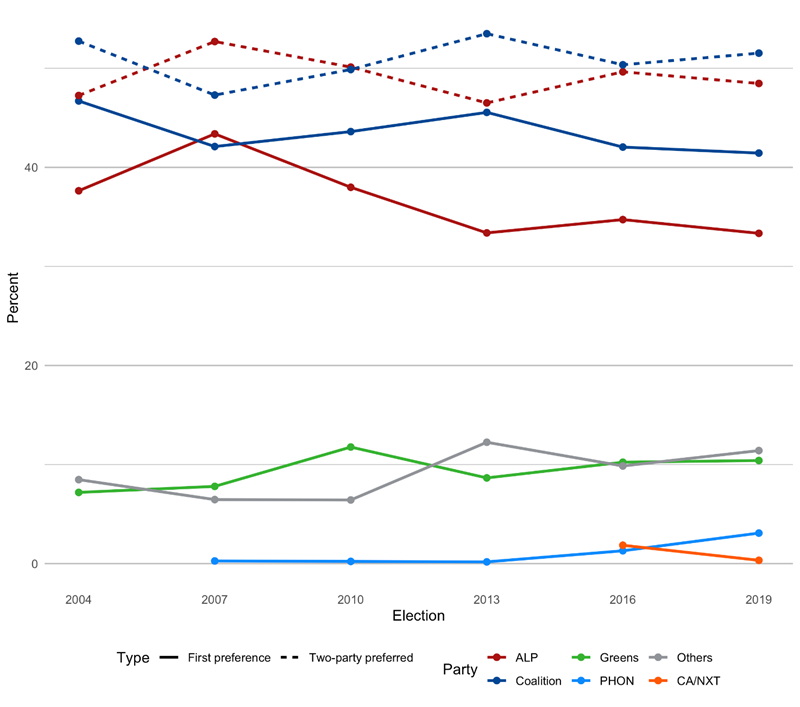

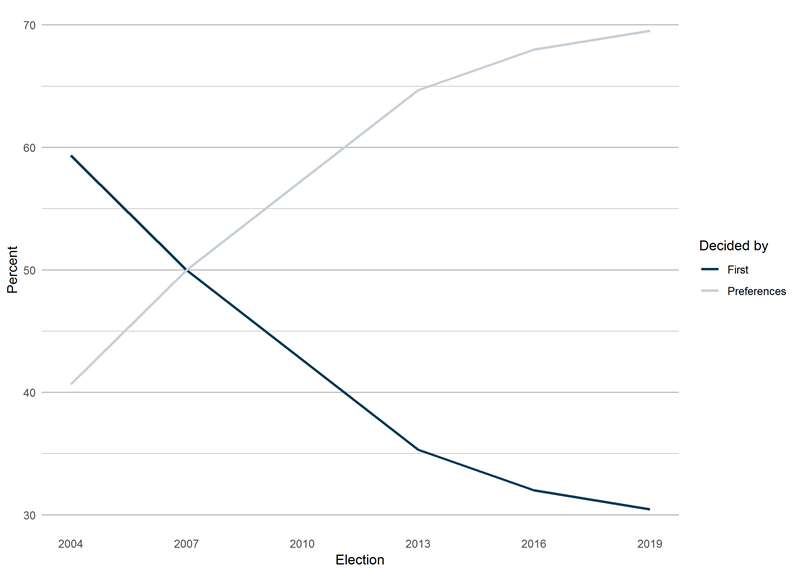

The 2019 federal election continued the trend of decreasing first

preference votes for both of the major parties, with both parties returning the

lowest primary vote for some years (Figure 1 below). This election saw the ALP

receive the lowest primary vote it had received since 1931 (when it received

27.1 per cent) and the lowest primary vote for the LP since it first contested

federal elections in 1946.[9]

In two-party preferred (TPP) terms the election saw a slight swing of 1.17

percentage points towards the Coalition compared to 2016, leaving the Coalition

with a 1.53 per cent winning margin.

Figure 1: First preference and

two-party preferred vote, federal elections 2004–

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Table 2: House of Representatives national results (top

15 parties), 2019 federal election

| Party |

Votes |

Percent |

Seats |

Swing |

| |

|

|

|

Votes |

Seats |

| Australian Labor Party |

4 752 160 |

33.34 |

68 |

-1.39 |

-1 |

| Liberal |

3 989 404 |

27.99 |

44 |

-0.69 |

-1 |

| The Greens |

1 482 923 |

10.40 |

1 |

0.17 |

0 |

| Liberal National Party of Queensland |

1 236 401 |

8.67 |

23 |

0.15 |

+2 |

| The Nationals |

642 233 |

4.51 |

10 |

-0.11 |

0 |

| United Australia Party |

488 817 |

3.43 |

0 |

3.43 |

0 |

| Independent |

479 836 |

3.37 |

3 |

0.55 |

+1 |

| Pauline Hanson's One Nation |

438 587 |

3.08 |

0 |

1.78 |

0 |

| Animal Justice Party |

116 675 |

0.82 |

0 |

0.12 |

0 |

| Christian Democratic Party (Fred Nile Group) |

97 513 |

0.68 |

0 |

-0.63 |

0 |

| FRASER ANNING'S CONSERVATIVE NATIONAL PARTY |

77 203 |

0.54 |

0 |

0.54 |

0 |

| Katter's Australian Party |

69 736 |

0.49 |

1 |

-0.05 |

0 |

| Centre Alliance |

46 931 |

0.33 |

1 |

-1.52 |

0 |

| Shooters, Fishers and Farmers |

41 479 |

0.29 |

0 |

0.18 |

0 |

| Country Liberals (NT) |

38 837 |

0.27 |

0 |

0.03 |

0 |

| Formal |

14 253 393 |

94.46 |

|

-0.48 |

|

| Informal |

835 223 |

5.54 |

|

0.48 |

|

| Total |

15 088 616 |

91.89 |

|

0.89 |

|

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

PHON polled better than it has in recent elections, with its

national first preference vote of 3.1 per cent an increase on the 1.29 per cent

it received in 2016. The result was well short of the 8.4 per cent national

primary vote it received in 1998, however, or even its next-best general

election result of 4.3 per cent in 2001. The party ran candidates in 59 seats

(primarily in Queensland (Qld) and Western Australia (WA)) and did not win any

lower house seats. In Qld ON received 8.86 per cent of the first preference

vote, a positive swing of 3.34 percentage points since 2016.

The Greens received a very slight positive national swing

(0.17 per cent), returning incumbent Adam Bandt in the division of Melbourne

(Vic.), and KAP received a very slight negative national swing (-0.05 per cent),

also returning the party’s only incumbent candidate, Bob Katter, in Kennedy

(Qld).

The Centre Alliance, which only ran candidates in three South

Australian seats, experienced a significant negative national swing (-1.52 per

cent) compared to the previous general election. CA incumbent Rebekha Sharkie

was returned in the division of Mayo (SA).

Three independents were elected. Andrew Wilkie was returned

in the division of Clark (Tas.) for his fourth term.[10]

Helen Haines, the designated successor of two-term independent Cathy McGowan,

won the division of Indi (Vic.), the first time an independent has been

replaced by another independent.[11]

Independent Zali Steggall won the division of Warringah (NSW) from eight-term

incumbent Liberal member and former Prime Minister Tony Abbott.[12]

Independent Kerry Phelps, who won the division of Wentworth

(NSW) at a by-election on 20 October 2018 following the resignation from

Parliament of former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, was not successful at the

2019 general election. The seat of Wentworth was returned to the Liberals, and

represented no net change for the division compared to the 2016 general

election.

The United Australia Party (UAP) ran candidates in all 151

electorates and received a primary vote of 3.4 per cent, failing to elect any

of its candidates. While not strictly a like-to-like comparison, the Palmer

United Party received 5.5 per cent of the primary vote in 2013, electing Clive

Palmer to the division of Fairfax (Qld).

Table 3: Two-party preferred

by state (percentage), 2019 federal election

| State |

Coalition |

Australian Labor

Party |

Swing to Coalition |

| New South Wales |

51.78 |

48.22 |

1.25 |

| Victoria |

46.86 |

53.14 |

-1.31 |

| Queensland |

58.44 |

41.56 |

4.34 |

| Western Australia |

55.55 |

44.45 |

0.89 |

| South Australia |

49.29 |

50.71 |

1.56 |

| Tasmania |

44.04 |

55.96 |

1.40 |

| Australian Capital Territory |

38.39 |

61.61 |

-0.48 |

| Northern Territory |

45.80 |

54.20 |

2.86 |

| National |

51.53 |

48.47 |

1.17 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

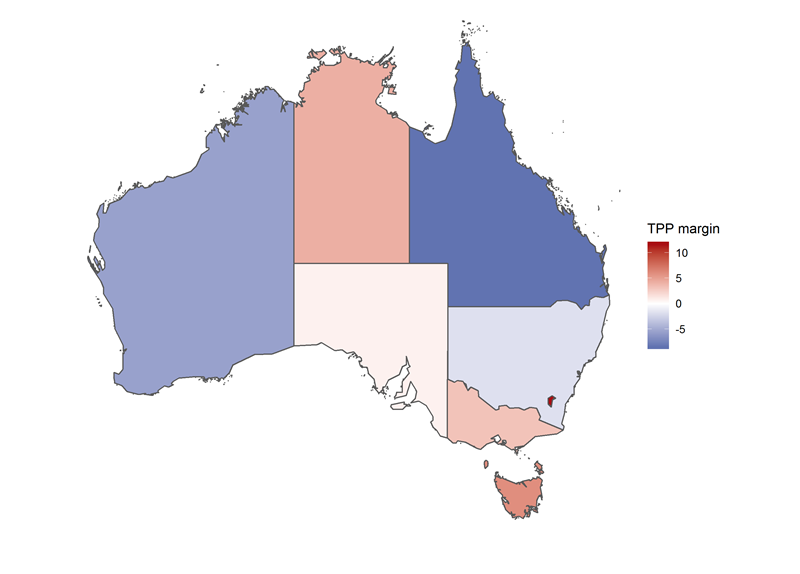

While the Coalition won the majority of the TPP vote in only

three of the eight Australian states and territories, these were three of the

four largest by number of voters (see Table 3 above and Figure 2 below). The

ALP won a majority of the TPP vote in a majority of the states and territories,

however as these included the smallest states and territories it meant the

Coalition led the ALP in TPP terms Australia-wide by about 436,000 votes. If Qld

were excluded, the ALP would have won a majority of the seats (62 for the ALP

compared to 54 for the Coalition).

Figure 2: Two-party preferred

margin by state, 2019 federal election

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

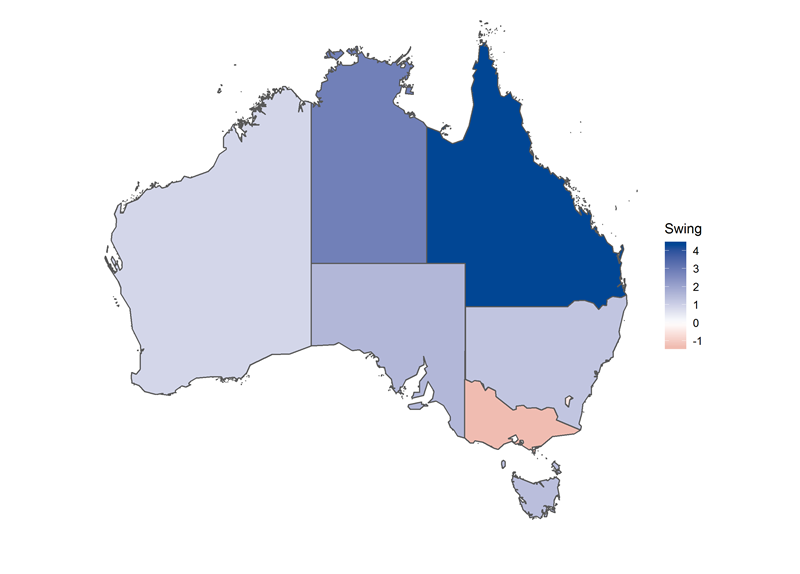

Figure 3: Two-party preferred

swing to Coalition by state, 2019 federal election

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

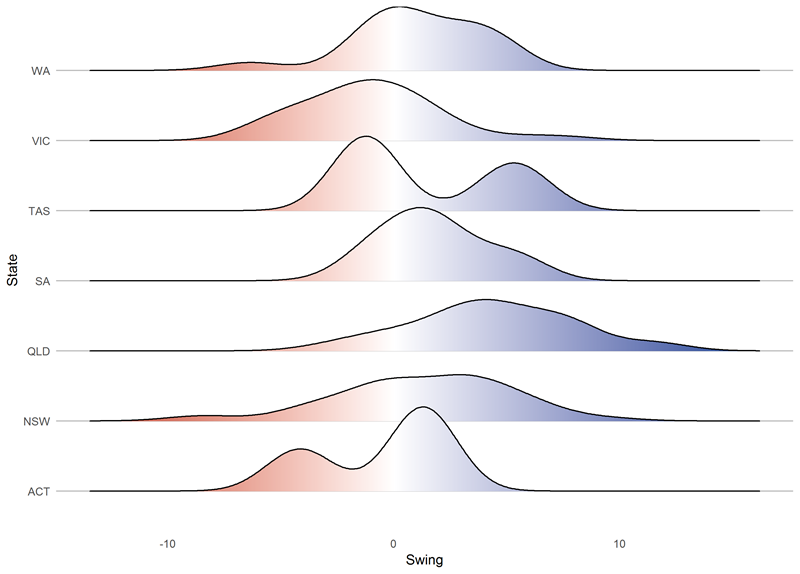

All states and territories except Victoria and the ACT

recorded a TPP swing towards the Coalition at the election (Table 3 and Figure 3 above). At the electorate level, most states and territories had electorates

that swung both to and against the Coalition. However in WA and Qld there was a

much stronger swing towards the Coalition across electorates. In Victoria

electorates tended to swing more to Labor, although to a lesser extent than the

swing to the Coalition in electorates in Qld (Figure 4 below).

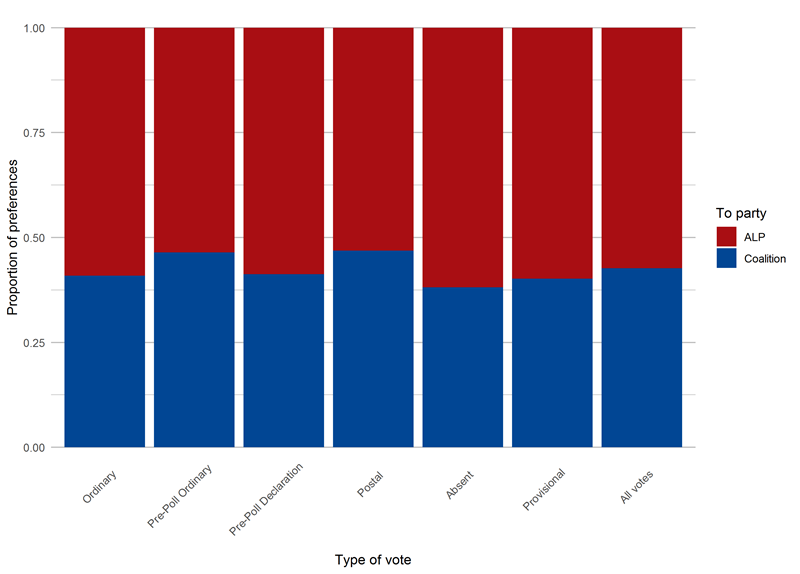

When examined by vote type, the Coalition performed more

strongly in early voting, leading the ALP by 9.2 percentage points in TPP

terms. Election-day votes were much more even, however, with Labor having a

slight two-party preferred lead in all types of election-day votes (Table 4 below).

Figure 4: Two-party preferred

swings to the Coalition by electorate for each state,

2019 federal election

Note: This chart shows what proportion of divisions in each

state swung to each party and by how much. The division of Whitlam was excluded

due to the AEC not reporting a TPP swing, and the NT has too few electorates

for a distribution to be calculated.

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Table 4: Two-party preferred

vote share by vote type, 2019 federal election

| Vote type |

Coalition (votes) |

ALP (votes) |

Coalition (%) |

ALP (%) |

| Postal |

699 547 |

514 117 |

57.64 |

42.36 |

| Pre-Poll Declaration |

300 964 |

292 914 |

50.68 |

49.32 |

| Pre-Poll Ordinary |

2 206 882 |

1 859 965 |

54.27 |

45.73 |

| Total Early |

3 207 393 |

2 666 996 |

54.60 |

45.40 |

| Absent |

267 677 |

309 819 |

46.35 |

53.65 |

| Ordinary |

3 849 803 |

3 905 494 |

49.64 |

50.36 |

| Provisional |

19 940 |

26 271 |

43.15 |

56.85 |

| Total Election Day |

4 137 420 |

4 241 584 |

49.38 |

50.62 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Preferences

Over two-thirds (almost 70 per cent) of the divisions were

decided by second or later preferences, meaning that the winning candidate

received less than 50 per cent of the first preference vote. Seats decided by first

or later preferences are given by winning party in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Seats decided by first

or later preferences by party, 2019 federal election

| Decided By |

LP |

ALP |

LNP (Qld) |

NP |

GRN |

IND |

KAP |

CA |

Total |

| First preference |

22 |

14 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

46 |

| Later preferences |

22 |

54 |

19 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

105 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

The number of seats decided by later preferences at this

election follows the trend in recent elections whereby the number of

electorates decided by later preferences has steadily increased (Figure 5 below).

Figure 5: Electorates decided

by first or later preferences, federal elections 2004–

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Of the 151 divisions at the election, 15 were what the AEC

refers to as ‘non-classic divisions’, where the final two candidates (the two-candidate

preferred—or TCP—candidates) were not Labor or Coalition candidates. The high (by

historical standards) number of ‘non-classic’ divisions makes examining

preferences more complex—preferences in ‘classic’ divisions always go to either

Labor or the Coalition, whereas in ‘non-classic’ divisions preferences will be

counted towards another party, or an independent candidate.[13]

When considering ‘classic’ divisions only, it is apparent that Labor won 54

seats overall on preferences compared to the Coalition’s 46 seats, and that, across

all vote types, Labor gained more than half of preferences (and in some cases

considerably more than half). However, early voting in ‘classic’ seats,

particularly postal and pre-poll ordinary votes, was more favourable to the

Coalition in terms of preference flows than election-day votes (Figure 6 below).

Figure 6: Share of TCP votes

by vote type in ‘classic’ divisions, 2019 federal election

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

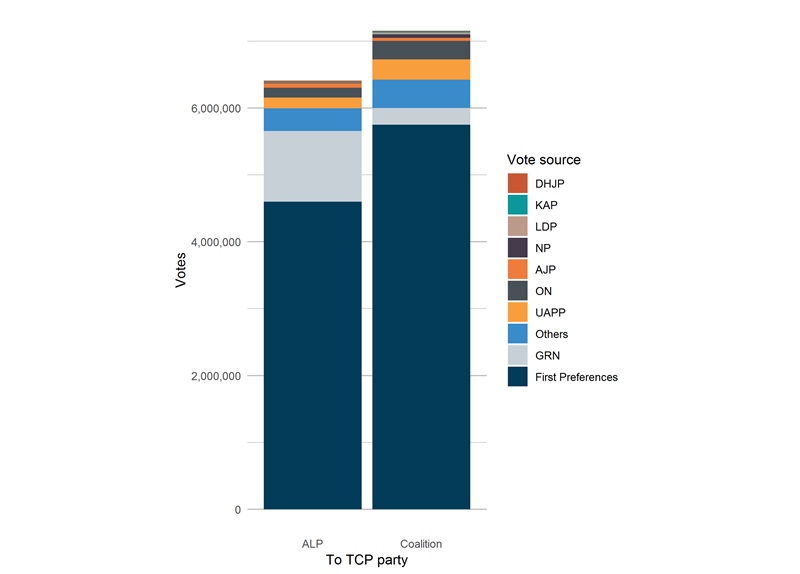

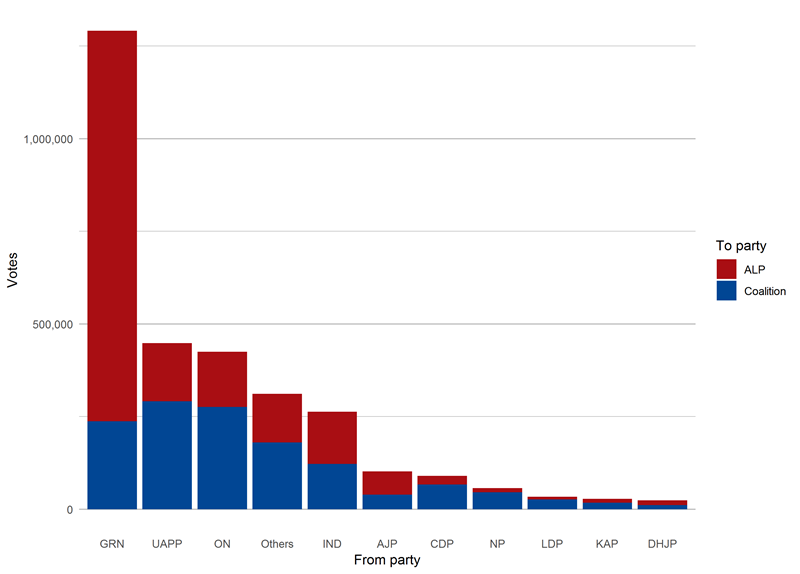

The observation that Labor did better than the Coalition in

terms of preferences in ‘classic’ seats may appear counter-intuitive given that

the Coalition won the election (in terms of both TPP vote and seats); however,

while Labor did receive a greater proportion of the preferences, it also

received considerably fewer first preference (primary) votes. As can be seen in

Figure 7 below, the Coalition received more primary votes in ‘classic’ seats

than the combined Labor primary votes and Greens preferences flowing to Labor.

Labor’s preferences flows, while strong, were insufficient compared to the

Coalition’s much stronger lead on primary votes.

Figure 7: Source of votes and

preferences in ‘classic’ seats by TCP party, 2019 federal election

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

The strong preference flows to Labor appear to have been

mostly driven by the Greens (Figure 7, above). Around 1.35 million Greens votes

flowed as preferences overall to TCP parties, with over one million of those

going to Labor and around 250,000 going to the Coalition. The number of Greens

preferences flowing to Labor therefore tends to overwhelm the preferences of

every other party, most of which tended to favour the Coalition (Figure 8, below). For example, PHON and UAP preferences were about twice as likely to

flow to the Coalition than to Labor.

Figure 8: Preference flows to the ALP and Coalition in

‘classic’ divisions, 2019 federal election

Note: ‘classic’ divisions are divisions where one of the two

candidate preferred candidates is from Labor and the other is from the

Coalition, and includes ‘three cornered contests’ where there is more than one

Coalition candidate in the division.

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Senate

The 2019 Senate election saw the predicted effect of the

2016 Senate voting system changes on minor party representation in the Senate

realised.[14]

Subject to a normal half-Senate quota, the only small parties other than the

Greens that won seats were PHON in Qld and the Jacqui Lambie Network (JLN) in

Tasmania (both of which incidentally returned senators who had been

disqualified during the section 44 crisis of the 45th Parliament). Both PHON

and the JLN were successful due to receiving a high proportion of the vote in

their respective states. In Qld PHON received the third highest vote by group,

with 0.72 quotas, and in Tasmania the JLN received 0.62 quotas, the fourth

highest vote in the state. The new Senate voting system has had the effect of

allowing small parties to gain Senate seats on the basis of votes rather than

preference deals.

The results of the Senate election by party and state are in

Table 6 below.

Table 6: Seats won by state in the Senate, 2019 federal

election

| State |

ALP |

LNP (Qld) |

LP |

NP |

Coalition

Total |

GRN |

JLN |

ON |

Total |

| NSW |

2 |

- |

2 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

6 |

| VIC |

2 |

- |

3 |

- |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

6 |

| QLD |

1 |

3 |

- |

- |

3 |

1 |

- |

1 |

6 |

| WA |

2 |

- |

3 |

- |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

6 |

| SA |

2 |

- |

3 |

- |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

6 |

| TAS |

2 |

- |

2 |

- |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

6 |

| ACT |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

2 |

| NT |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

2 |

| Total |

13 |

3 |

15 |

1 |

19 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

40 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

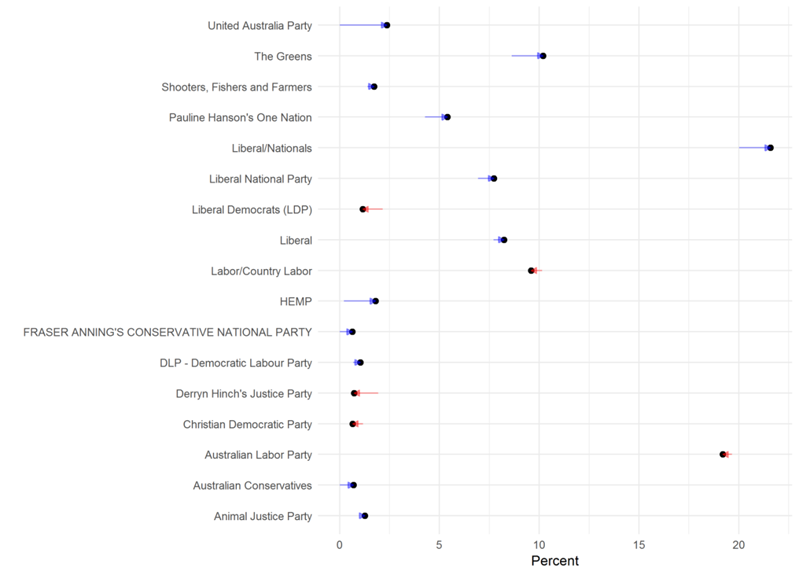

Figure 9: National Senate

primary votes (dots) and swings (arrows) by party group, 2019 federal election

Note: only includes parties that received at least 0.5 per cent

of the national first preference vote. Some parties occur multiple times due to

running under different group names in different states—the AEC does not

provide the data required to calculate swings for combined groups.

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Smaller parties tended to do well in

the Senate election, with many recording a positive swing compared to the 2016

election, with notable exceptions in Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party and the

Liberal Democrats—two parties that were represented in the Senate prior to the

2019 election (Figure 9 above). In general, however, these positive swings

were not sufficient to make the parties competitive with the more established

parties in terms of winning seats. The largest negative national swing was

recorded by the CA, which saw a 3.11 percentage point drop in its vote from

2016.

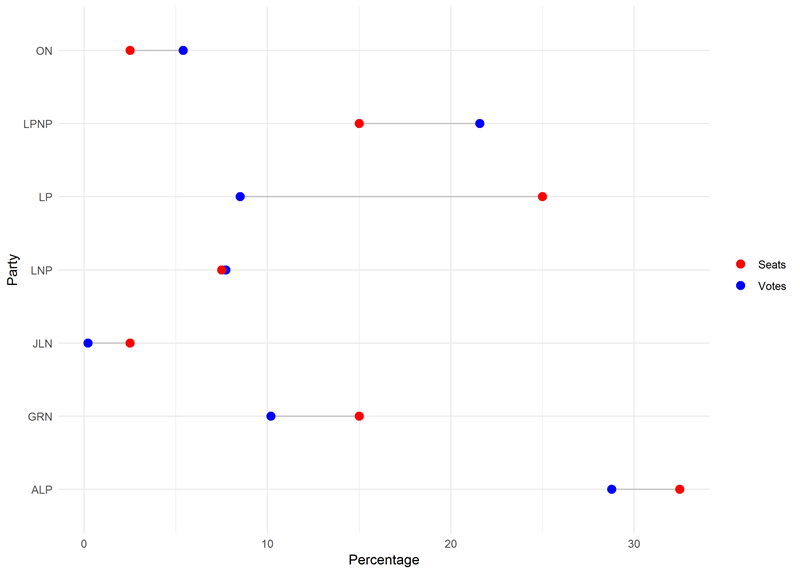

Figure 10: National Senate votes (blue) and seats (red)

by party group, 2019 federal election

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from AEC election

results data.

Nationally, the Senate seat share of the LP, the Greens, the

JLN and the ALP tended to out-perform the parties’ vote share. The Liberal

National Party (LNP) of QLD received an unusually proportional 7.5 per cent of

the seats for 7.7 per cent of the vote (Figure 10 above). The high seat

performance relative to votes for the LP is likely due to having done

relatively well in small states (WA, SA and Tasmania), where a large state-wide

vote share is relatively small on a national level, however still results in

winning seats.

As discussed in the introduction to this paper, due to the section

44 citizenship crisis the composition of the Senate immediately prior to the

2019 election looked quite different from that of the Senate elected in 2016.

The net change as a result of the 2019 election was generally a loss of most of

the non-Greens minor party senators, with the seats being picked up by the

Coalition (Table 7 below).[15]

As elected, the resulting Senate was much more favourable to the Government for

passing legislation. If the ALP and the Greens chose to use their 35 combined

votes against the Government in the Senate, the Coalition Government only needed

four more votes from the six cross-benchers, in addition to its 35 votes, to

pass legislation. With the resignation of independent Senator Cory Bernardi

(SA) in January 2020 and his replacement by Liberal Senator Andrew McLachlan on

6 February, the Government gained one more Senate vote, meaning that it needs just

three votes from five crossbench senators to pass legislation.[16]

Table 7: Senate composition

following the 2019 federal election

| Party |

Terms end

30/06/2022 |

Terms end

30/06/2025 |

Terms end next

election |

Total |

Change |

| LP |

14 |

15 |

2 |

31 |

5 |

| ALP |

13 |

11 |

2 |

26 |

0 |

| GRN |

3 |

6 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

| NP |

2 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

-1 |

| CA |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

| PHON |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

| IND |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

-1 |

| JLN |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Others |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-4 |

Note: The following parties were no longer represented in the

Senate following the 2019 election: Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party (DHJP), the

Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the United Australia Party, and, after 25 June

2019, the Australian Conservatives (AC). Senator Cori Bernardi disbanded the AC

party to sit as an independent prior to the Senate first sitting following the 2019

election. Territory senators do not have fixed terms; their terms end at the

next general election.

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library

Timing of

the election

The timing of the 2019 federal election was the subject of

considerable speculation from late 2018. The 2016 double dissolution election

meant that a half-Senate election was required to be held between July 2018 and

May 2019 for the senators elected in 2016 for a short term.[17]

Further complicating the choice of election date were fixed-term elections due

in NSW (23 March 2019) and Victoria (24 November 2018), and the Federal Budget,

traditionally held in early May. The Budget was moved to 2 April 2019 to

accommodate the election timing.

Media reports stated that Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull

had intended to call an election on 27 January 2019 for a 2 March election day,

in order to go to the polls before the NSW state election.[18]

By April 2019, however, new Prime Minister Scott Morrison was leaving open the

possibility of a May election.[19]

There was some debate over election timing in respect of how

late an election could be held.[20]

Prior to the announcement of the election there was some speculation that it

could be held as late as 25 May 2019,[21]

and while the Electoral Commissioner did not dismiss the possibility, he noted

that ‘the later we go, the more complex it becomes for the AEC but that does

not mean it is impossible.’[22]

On the morning of Thursday 11 April 2019 the Prime Minister

visited the Governor-General and advised the dissolution of the 45th Parliament

for a general election on Saturday 18 May 2019.[23]

The key dates the Prime Minister nominated (and consequential dates that follow

from those) are listed in Table 8 below.

Table 8: Key dates for the

2019 federal election

| Milestone |

Date |

| Issue of the writs |

Thursday 11 April 2019 |

| Close of the rolls |

Thursday 18 April 2019 |

| Close of nominations |

Tuesday 23 April 2019 |

| Declaration of nominations |

Wednesday 24 April 2019 |

| Early voting commences |

Monday 29 April 2019 |

| Election advertising blackout commences |

Wednesday 15 May 2019 |

| Polling day |

Saturday 18 May 2019 |

| Writs returned |

Friday 21 June 2019 |

| Last day for return of the writs |

Friday 28 June 2019 |

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library

The Parliament was prorogued at 8.29am on 11 April 2019, and

as such the Senate Estimates hearings scheduled for 11 and 12 April 2019 did

not proceed.

While recent elections have generally been announced on a

weekend, with the writs issued early the following week, the 2019 election

timing provided complications with both Easter and Anzac Day occurring within

the election period.[24]

The timing of the election is dictated by the Commonwealth

Electoral Act (1918) (CEA), which nominates a minimum 33 day period between

the issue of the writs and polling day.[25]

The 2019 election period was 37 days, slightly above the average for elections

since 1984 of 35.6 days. The writs were due to be returned 41 days after

polling day, in time for the new Senators to commence their terms on Monday 1

July 2019, and were returned with a week to spare on Friday 21 June 2019.[26]

The CEA requires that close of the rolls must happen

seven days after the issue of the writs (section 155) and the close of

nominations between 10 and 27 days after the issue of the writs (section 156).

Issuing the writ on Monday 15 April would have meant that the close of rolls

would have been on Easter Monday (and for an 18 May election the close of

nominations would have had to have been on Anzac Day).

While the campaign period included public holidays, early

voting did not commence until Monday 29 April (five days after the declaration

of nominations, which is 24 hours after the close of nominations, under

subsection 200D(4) of the CEA), and so was not interrupted by any public

holidays. Prior to the election being called the Electoral Commissioner had stated

at Senate Estimates that if Anzac Day had fallen within the pre-poll period

then pre-poll voting would not be available on that day.[27]

The Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition agreed not to campaign or run

political advertising on Good Friday, Easter Sunday or Anzac Day (however this

truce was not observed by all campaigners).[28]

Redistributions

One year after a new Parliament first meets, the CEA

requires that the AEC use the latest population statistics to determine how

many electorates each state and territory is entitled to using a formula based

on section 24 of the Australian Constitution. The entitlement

determination that occurred in the 45th Parliament required that SA lost one

seat and Victoria and the ACT gained one seat each due to their relative

population changes.[29]

For the first time 151 Members of the House of Representatives were elected at the

2019 federal election.

The 45th Parliament also saw electoral redistributions in Qld,

the NT and Tasmania due to seven years having passed since those jurisdictions

last had redistributions.

The redistribution of Qld was completed on 27 March

2019, and made relatively minor changes to the boundaries. The redistribution

retained the names of all 30 seats and adjusted the boundaries of 18 seats,

with 33,604 electors (1.09 per cent of all enrolled Queensland electors)

changing seats.[30]

The redistribution of Victoria was completed on 13

July 2018 and resulted in the creation of a new division of Fraser located in

the western suburbs of Melbourne (in honour of the former Prime Minister

Malcolm Fraser), resulting in a total of 38 electoral divisions. The

redistribution also renamed the division of McMillan to Monash, in honour of

Sir John Monash; the division of Melbourne Ports was renamed to Macnamara in

honour of Dame Annie Jean Macnamara; the division of Murray was renamed to

Nicholls in honour of Sir Douglas Ralph Nicholls and Lady Gladys Nicholls; and

the division of Batman was renamed to Cooper in recognition of William Cooper.

The names of the remaining 33 divisions were retained. A total of 769,523

electors (18.93 per cent of enrolled Victorian electors) changed their division

as a result of the redistribution, and an additional 435,141 electors (10.71

per cent of enrolled Victorian electors) were in a division that was renamed.[31]

The redistribution of the ACT was completed on 13 July

2018 and resulted in the creation of a third electoral division for the ACT,

which was named Bean in honour of Charles Bean. The naming of the electorate

resulted in a number of objections, with the augmented Electoral Commission

voting four to two in favour of Bean. The redistribution resulted in 151,218

electors in the ACT (52.44 per cent of all enrolled ACT electors) changing

their division.[32]

The redistribution of SA was completed on 20 July

2018 and resulted in the abolition of the division of Port Adelaide. In

addition, the division of Wakefield was renamed to Spence in honour of

Catherine Helen Spence. The boundaries of all South Australian divisions were

adjusted and 255,784 electors (21.40 per cent of all enrolled South Australian

electors) changed division as a result.[33]

The redistribution of the NT was completed on 7

February 2017 and resulted in an adjustment of the boundaries of the two

divisions and the movement of 2,680 electors (2.07 per cent of enrolled NT

electors) who changed divisions.[34]

The redistribution of Tasmania was completed on 14

November 2017 and resulted in adjustments of the boundaries of Bass and Lyons

and renaming of the division of Denison to Clark in honour of Andrew Inglis

Clark. The redistribution resulted in 22,800 electors (6.08 per cent of enrolled

Tasmanian electors) changing divisions.[35]

The abolished seat of Port Adelaide in SA was held by Labor,

but the new seats of both Bean (ACT) and Fraser (Vic.) were notional Labor,

giving Labor a national net gain as the result of the redistributions. The divisions

of Corangamite and Dunkley in Victoria, both won in 2016 by the Liberals, were

notionally ALP following the redistribution (by 0.03 percentage points and 1.25

percentage points respectively).[36]

The election

campaign

The 2019 federal election campaign was generally

unremarkable. The Coalition went into the election behind in the polls, however

while the Coalition was out-polled by Labor throughout the campaign, the gap

between the two parties closed across the election period.

The Coalition had its third Prime Minister since Tony Abbott

led the Coalition to government in 2013, while the ALP’s leadership team was

largely unchanged since Bill Shorten took the leadership of the party in

October 2013 following the defeat of the Rudd government.

Most commentators expected an ALP victory, if possibly a

narrow one.[37]

In particular, it was predicted that Labor would pick up two to three seats

from the Liberals in Victoria and win seats from the Liberals in NSW, but would

probably not win additional seats in Qld.[38]

The campaign was shaken by the death, two days before the

election, of former Labor Prime Minister Robert ‘Bob’ Hawke. Media reports

suggested that both major parties held the view that the death of Mr Hawke

would be generally beneficial for Labor’s election efforts.[39]

The ALP was the first of the major parties to hold a

campaign launch, doing so in Brisbane on Sunday 5 May. The launch featured

former prime ministers Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, and Bill Shorten

articulated Labor’s campaign promises on health, tax cuts, education, climate

change and fairness.[40]

The Coalition campaign launch was held in Melbourne on Mothers’ Day, Sunday 12

May. Commentators noted that the launch was focused almost exclusively on Scott

Morrison as leader, in part to shift focus from the leadership instability that

the party had experienced in the past six years.[41]

While it had been the case that the parties had an agreement

not to claim travel allowances after the campaign launch, a media report prior

to the election stated that at the 2019 election ‘both sides of politics can

travel on chartered and domestic flights and claim travel allowance all the way

to election day’.[42]

Post-election media reports stated that in April, May and June cabinet

ministers’ staff accumulated $5 million in travel expenses, and shadow

ministers’ staff around $1.6 million.[43]

The policy contest

The federal Budget, usually delivered in May, was delivered

on 2 April 2019, and was viewed by commentators as an ‘election budget’. The

Budget featured tax cuts, both immediate and into the future, and a commitment

to return the Budget to a small surplus, though was otherwise restrained in

terms of new spending.[44]

The Coalition largely relied on the Budget, delivered two weeks before the

election period began, as the foundation of its campaign, with a focus on

maintaining a strong economy.[45]

A statement by the Prime Minister proposed that voters ‘have

the choice between the LNP that is delivering a strong economy and will

continue to do so, or Bill Shorten and the Labor Party, who are proposing

massive new taxes that will only weaken our economy’.[46]

Bill Shorten, in a statement to voters, asserted that the Government ‘has no

agenda for the next three years apart from a plan to give a $77 billion tax

handout to the top end of town’.[47]

Labor went to the election with largely the same suite of

policies that had delivered it an almost three per cent swing and 49.6 per cent

of the two-party preferred vote at the 2016 federal election. Labor’s promises

amounted to an extensive list of expenditure measures along with a number of

savings measures to fund them. The highest profile savings measures were the

abolition of negative gearing on all but newly-built investment properties

(grandfathering existing negative gearing), and the cessation of tax rebates

for franking credits.[48]

These two policies were calculated to save the budget $14.2 billion over the following

four years and $32 billion in a decade, respectively.[49]

The Opposition Leader conceded that Labor’s campaign promises, particularly in

relation to the savings issues, ‘have given our opponents plenty of ammunition

for their endless scare campaigns’.[50]

One aspect of the campaign that was considered significant (mostly

in retrospect) was the position of the ALP on the proposed Adani coal mine in

Queensland. Labor’s climate change position, which was viewed as being

anti-coal, was reported prior to the election as damaging Labor’s chances of

picking up rural and regional Queensland seats, although it was expected that

Labor would do better in Brisbane.[51]

While Labor generally attempted to avoid taking a position on the Adani mine,

noting that environmental approvals had already been granted by the Government,

one significant union threatened to campaign against candidates if it looked

like Labor would not support the mine proceeding.[52]

The Greens argued that the Adani mine ‘can’t be built’, and

former Greens leader Bob Brown led a convoy from Hobart to the mine site in the

Qld Galilee Basin to protest against the mine.[53]

After stopping at Clermont in central Qld, the convoy finished at Parliament

House in Canberra prior to the election.[54]

In the wake of the election, Greens leader Richard Di Natale concluded that the

convoy had harmed Labor in the election ‘because the Labor party refused to

take a clear position’.[55]

Similarly, a Labor MP who lost a central Qld seat agreed that the way Labor’s

climate policy was conveyed alienated blue-collar workers.[56]

According to Labor’s official review of its campaign:

Labor’s ambiguous language on Adani, combined with some

anti-coal rhetoric and the Coalition’s campaign associating Labor with the

Greens in voters’ minds, devastated its support in the coal mining communities

of regional Queensland and the Hunter Valley.[57]

Candidate

disendorsements

The election saw an unprecedented number of candidates

either resign or lose their party endorsement. There is no provision in the CEA

for the removal from the ballot paper of candidates who resign or who are

disendorsed by their party after the close of nominations. For the 2019 federal

election ten candidates resigned or were disendorsed by their party after the

close of nominations:

- Gurpal Singh (Scullin, Vic.), Liberal

- Luke Creasey (Melbourne, Vic.), Labor

- Peter Killin (Wills, Vic.), Liberal

- Jeremy Hearn (Isaacs, Vic.), Liberal

-

Jessica Whelan (Lyons, Tas.), Liberal

- Steve Dickson (Qld Senate), One Nation

- Wayne Kurnorth (NT Senate), Labor

- Jay Dessi (Lalor, Vic.), Greens

- Tony Pecora (Melbourne, Vic.), United Australia and

- David Paull (Parkes, NSW), Greens.

While none of the disendorsed candidates were elected, some

polled well despite their disendorsement (Jeremy Hearn received 35 per cent of

the vote in Isaacs, coming second behind the winning Labor candidate, for

example).

As a response to the string of disendorsements the Victorian

Liberal Party brought forward its preselection process for the next federal

election, closing nominations in January 2020.[58]

However the candidates’ votes, due to be conducted in March 2020, have at the

time of publication been delayed indefinitely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[59]

Candidates who are disendorsed by

their party after the close of the nominations continue to have their original

party listed against their name on the ballot paper, and the party will receive

per-vote public funding for any votes received by such candidates. The public

funding scheme was changed prior to the 2019 federal election, with parties and

candidates being required to submit a claim to the AEC for reimbursement of

campaign expenditure up to the public funding amount. On the basis of the

public funding rate and the votes the candidates received, the Liberals were

eligible for around $246,000 in public funding from the votes from their

disendorsed candidates, Labor around $51,000, and the Greens around $31,000.

None of the disendorsed Senate candidates received sufficient votes to reach

the four per cent threshold to qualify for public funding.

Electoral

advertising on social media

Authorisation

requirements

Following changes to the CEA by the Electoral and

Other Legislation Amendment Act 2017 (Cth), the requirements to authorise

electoral advertising were expanded and in some cases clarified to explicitly

cover electoral advertising by social media.[60]

The AEC is responsible for administering and enforcing the

authorisation provisions. A pre-election report in The Guardian noted

the AEC’s strategy for policing social media advertising:

The AEC said in a statement that generally unauthorised paid

electoral ads infringe on the Commonwealth Electorate Act. But given the volume

of material on Facebook and other channels, the AEC said it “benefits” from

public reports to identify where the law has been breached.

Once alerted, it contacts the Facebook group and asks for the

ad to be authorised or removed.

“If the infringement is not addressed, the AEC can contact

the relevant social media provider to advise them to remove the unauthorised

electoral advertisement,” a spokesman said. “The AEC may also consider legal

action, such as an injunction to prevent the further display of the unlawful

advertising, and, in serious cases, civil penalties for breaching the Electoral

Act.”[61]

More recently the AEC has indicated that it had positive

interactions with social media providers in respect of the 2019 election. In

December 2019, in evidence to the parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on

Electoral Matters (JSCEM) inquiry into the 2019 federal election, the Electoral

Commissioner stated:

At the last event, we had more interaction and, I would say,

better cooperation with the social media companies than we've ever had

previously. It was the first election where our interaction was comprehensive

before and during, and we're pretty happy with what we achieved with them as a

one-off... It wasn't just with Twitter, Google and Facebook; we also reached out

to WeChat. As you know, in Australia there are a very large number of users of

WeChat as well. [62]

In its post-election submission to the JSCEM inquiry, the

AEC stated that it had received 1,072 enquiries and complaints relating to

electoral communication (an increase on what was received in relation to the 2016

election). It provided advice in relation to 544 of these and investigated 528,

of which 109 (some 20 per cent) related to social media communications. The

outcomes of the 528 investigations are detailed in Table 9 below.[63]

Table 9: Electoral communication

investigated by the AEC at the 2019 federal election

| |

Communications

investigated |

No breach |

Breach (s 321D) |

Breach (s 329) |

| Social media |

109 |

81 |

25 |

3 |

| Signs and print |

223 |

183 |

47 |

3 |

| Other communications |

186 |

175 |

10 |

1 |

| Total |

528 |

439 |

82 |

7 |

Source: Australian Electoral Commission[64]

Note: Section 321D of the CEA relates to improper authorisation

of electoral communication and section 329 relates to electoral communications

that mislead or deceive an elector in relation to the casting of a vote.

In the report the AEC stated that it issued 78 warnings in

relation to breaches and took further action on 11 matters where the

infringement was not addressed following the warning by asking the social media

company to remove the material.[65]

Transparency

of electoral advertising on Facebook

In light of recent criticisms of the lack of transparency of

political advertising on Facebook, Facebook has introduced an ‘Ad

Library’, which aims to make public otherwise ‘dark’ (that is, not publicly

viewable) targeted political advertising. An ABC report shortly after the 2019

election noted that Facebook’s Ad Library did not include information such as

the demographic targeting of ads, as is available in some regions. It was also reported

that Facebook would make the data available globally in June 2019 (Ad Library now

contains Facebook ads from Australian political parties and candidates).[66]

In evidence to the JSCEM the AEC noted that, according to

Facebook, Ad Library was not available in relation to political advertising for

the 2019 federal election due to a number of elections internationally.[67]

In April 2019 Facebook had published a blog post in which it discussed Ad

Library in the context of the election, stating that it would ‘shin[e] a

brighter light on advertising and Pages [which] makes both Facebook and

advertisers more accountable, which is good for people and good for democracy’.

Facebook also stated that it would block foreign electoral advertising:

Combating foreign interference is a key pillar of our

approach to safeguarding elections on our platform. As part of this commitment,

we’re temporarily not allowing electoral ads purchased from outside Australia

ahead of the election in May.

The restriction will take effect the day after the election

is called and will apply to ads we determine to be coming from foreign entities

that are of an electoral nature, meaning they contain references to politicians,

parties or election suppression. We also won’t allow foreign ads that include

political slogans and party logos.[68]

Due to the limited transparency of political advertising on

Facebook at the time of the 2019 election, both the

Guardian and the ABC

launched initiatives encouraging people to take screenshots of political

advertising and to share these with the media organisations for archiving. The

Guardian’s archive is still available, although the ABC archive appears no

longer to be accessible.

The Guardian published some analysis of the Facebook ads

that were submitted to it and data provided by Facebook’s Ad Library, finding

that ads sponsored by political campaigns were targeted in a range of ways, for

example towards particular demographics or specific interests that might be

affected by significant election policies. The Guardian’s analysis also found

‘many’ ads without proper authorisation information, including ads from

anonymous pages.[69]

One particular stream of social media election advertising

that has been investigated in some depth related to material suggesting that

Labor had plans to introduce a death tax if it was elected. According to an

investigation by The Guardian, the death tax material was widely shared

on Facebook, and the belief that Labor would introduce a death tax was

encountered by Labor MPs campaigning for the election.[70]

The Guardian report found that claims Labor was in favour of a death tax

could be traced back to a Daily Telegraph article from July 2018 regarding

Australian Council of Trade Unions support for an inheritance tax;[71]

a follow-up discussion on the ‘Sunrise’ television program the next day; and a subsequent

media release by the Treasurer in January 2019.[72]

The report states that at first the spread of the material

was relatively organic:

The Sunrise clip was shared by One Nation leader Pauline

Hanson’s official Facebook account the same day it aired. Hanson’s post alone

was viewed 106,000 times. LNP members Ian MacDonald and George Christensen began

to push the death tax messaging from their Facebook pages in late January and

early February, but their posts achieved relatively little engagement.[73]

The Guardian noted that the material spread rapidly

in the lead-up to the election and was forwarded to people via direct Facebook

message. The same message was also being spread by minor parties and others:

The death tax messaging on social media was being amplified

by minor parties, including Clive Palmer’s United Australia party, which was

engaged in saturation advertising, by fringe right-wing groups, and by

individual Coalition senators. The LNP backbencher George Christensen published

three Facebook posts on the topic on one day, 22 April. Christensen’s first

post was titled “Labor’s secret plans for a DEATH TAX”. A day later, Rite-On, a

right-wing group with a significant online following, published a post

headlined “DEATH TAX – INHERITANCE TAX – DEATH DUTY, call it what you will, it

will hit us all”.[74]

Exactly who was responsible for the rapid spread of the

death tax message remains unclear; however the information in the report might

seem to indicate that it was more than just organic spread of a message that

caught the attention of a sub-set of the electorate.

Even if Facebook’s Ad Library had been in full operation

in the 2019 federal election, it is difficult to know how effective it would

have been in revealing any organisation behind the death taxes campaign. The Guardian

reports that the campaign did involve some paid Facebook advertising by

candidates and campaigns, which should have been caught by Ad Library; but

sharing by groups and individuals would likely not have been exposed by Ad

Library. It is therefore questionable whether Facebook provides the tools to

render transparency to these sorts of campaigns.

In a policy shift that happened after the federal election, Facebook

has recently stated that posts shared by politicians are not subject to

Facebook’s community standards or fact-checking.[75]

Facebook has stated that it exempts politicians from its fact-checking program,

but that if a politician shares previously debunked content it will be

‘demoted’ (however paid ads must be consistent with Facebook’s ‘Community

Standards’, and debunked content cannot be displayed in paid ads).[76]

Google has stopped allowing political ads to be targeted to search users, and

Twitter has stopped accepting paid political advertising.[77]

Expenditure

on social media electoral advertising

How much of the electoral advertising spend in Australia

goes on social media is impossible to accurately determine. Australian federal

political finance laws do not require parties to disclose their election

campaign spending—parties are only required to report annual total income,

donations, expenditure and loans, and are not required to state what proportion

of the expenditure related to a campaign.

Media monitoring companies also tend not to provide social

media campaign spending estimates as they do with traditional broadcast media,

at least partly because much of the advertising is micro-targeted and so only

appears to certain users.[78]

Television, radio and print advertising, on the other hand, is by definition

public, and more closely monitored, allowing spending estimates to be made. For

example, for the 2016 election an estimated $16m was spent on television, radio

and print advertising, 90 per cent of it by the Coalition and the ALP; for the

2019 federal election, by mid-March 2019 Clive Palmer alone had already spent

an estimated $21m.[79]

In contrast, it has been estimated that the major party spends on online and

social media advertising would constitute around 20 to 30 per cent of the total

ad spend.[80]

Election appeals: citizenship

and purple signs

In its inquiry report on the section 44 crisis, the JSCEM

recommended that, in the absence of a referendum to change the Constitution,

the Government should consider strategies to mitigate the impact of section 44,

such as ‘that all candidates for election be required to make a public

disclosure of family citizenship history at time of nomination.’[81]

The Government responded to this recommendation by passing the Electoral

Legislation Amendment (Modernisation and Other Measures) Act 2019 (Cth),

which requires that, as part of the nomination process, all election candidates

are required to disclose certain information in relation to the eligibility

criteria in section 44.[82]

In relation to the 2019 federal election, this measure appears to have been

successful, as only one substantive section 44 challenge—which was subsequently

dismissed by the court—was filed in the wake of the election (however former

senator Rodney Culleton was referred to police by the AEC for submitting a

nomination form stating he was eligible while he was listed as an undischarged

bankrupt[83]).

The section 44 challenge that resulted from the election was

to the eligibility of the member for Kooyong (Vic.), federal Treasurer Josh

Frydenberg. Mr Frydenberg’s eligibility had come under question at the height

of the section 44 crisis, but the question of his eligibility was not referred

to the High Court.[84]

The High Court’s 2018 decision in Alley v Gillespie

confirmed that the only way for the eligibility of a member or candidate to be

challenged on the basis of section 44 was by a referral from the relevant

Chamber of Parliament, or in the 40 days after the return of the writ for the

election under section 355 of the CEA.[85]

The petition lodged by Michael Staindl against Mr Frydenberg claimed that Mr

Frydenberg was not eligible to sit in the Parliament as he was a citizen of the

Republic of Hungary.[86]

The challenge against Mr Frydenberg’s eligibility was labelled by critics as

being anti-Semitic and ‘disgraceful’ (Mr Frydenberg’s mother was a Holocaust

survivor).[87]

The Federal Court, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns,

dismissed the challenge on 17 March 2020, concluding that Mr Frydenberg ‘was

not, and never has been, a citizen of Hungary’. Mr Staindl was ordered to pay

costs.[88]

On the subject of election signs, two other petitions

related to the same election signage in both Mr Frydenberg’s electorate of

Kooyong and in the division of Chisholm, which elected Liberal candidate Gladys

Liu.[89]

The High Court, sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns, referred the petitions

for trial to the Federal Court of Australia.[90]

The petitions related to signs at polling places in the two electorates that

were authorised by the Liberal Party. The signs were in Chinese characters and

were in the distinctive purple colour (or a very similar colour) that has been

a feature of the AEC’s branding since 2007. The petitions argued that the signs

were likely to mislead voters as they translated to instructing voters that the

‘correct’ way to vote was to put a ‘1’ next to the LP candidate.[91]

On 24 December 2019 the Federal Court, sitting as the Court

of Disputed Returns, dismissed the petitions. The Court concluded that the

signs were misleading and deceptive in that they purported to be from the AEC

and they stated that the ‘correct’ way to vote was to vote for the Liberal

Party. The Court found that, even if voters were influenced by the signs, it

would not have been in sufficient numbers to affect the result of the election.

The Court ordered that the LP official who authorised the

signs demonstrate to the court why their authorisation of the signs was not an

illegal act under section 329(1) of the CEA.[92]

On 20 February 2020 the Court found that it had insufficient evidence to

determine that the official had the requisite state of mind and knowledge to

have breached the Act and did not proceed any further with the case.[93]

Clive Palmer’s

High Court case on the early release of election results

Under Australia’s preferential voting system, each election

in each division comes down to a contest between two candidates, with the

preferences on the votes for all of the other candidates eventually counting

towards one of those two candidates. To expedite the count, the AEC chooses the

candidates most likely to be the final two candidates in each division, and

conducts and publishes a preference count against those candidates. The count

is referred to as the ‘two-candidate preferred’ (TCP) count, and these

candidates are the TCP candidates. The TCP candidates are not made public by

the AEC until after the polls have closed in that division.

In April 2019 Clive Palmer took the AEC to the High Court,

arguing that the AEC’s practice of choosing two candidates in each division

might reduce the incentive for voters in parts of the country where the polls

are still open due to time zone differences to vote for minor parties or

independents. He sought orders from the Court to prevent the AEC publicly

revealing the predicted final two candidates in any electorate until all of the

polls in the country had closed.[94]

The High Court unanimously dismissed the case on 7 May 2019.

In reasons published in August 2019, some months after the election, the Court

stated that Mr Palmer’s contention that releasing the predicted final

candidates was not authorised under the CEA, and that releasing the

information would distort the voting system ‘lacked a factual foundation’.[95]

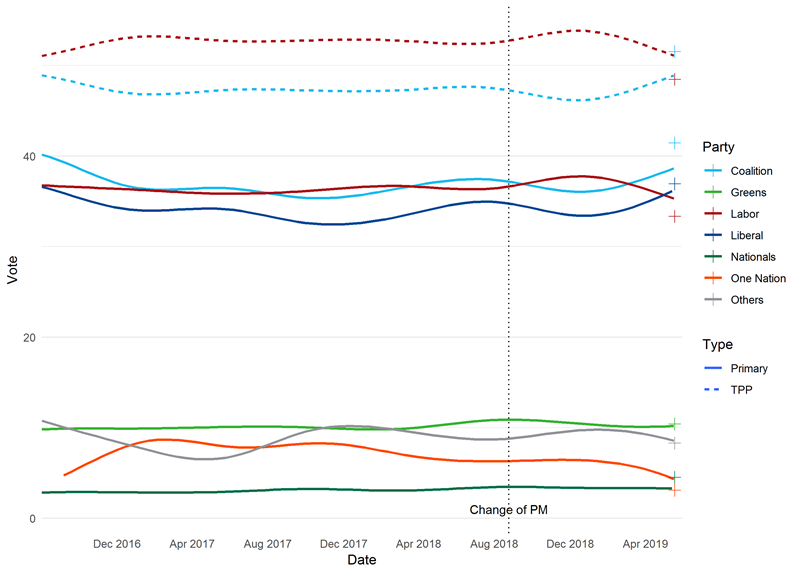

The opinion polling

failure

In the time period between the 2016 federal election and the

2019 federal election the Coalition only received a TPP opinion (voting

intentions) poll result above 50 per cent twice, both in 2017 in the

short-lived YouGov poll series.[96]

For the majority of the term of the 45th Parliament, and for the entirety of

the term in the case of the most prolific pollsters, Labor led the polls in TPP

terms (Figure 11 below). While the polls in the lead-up to the election showed

a narrowing of the gap, the final polls of all of the major polling companies

predicted a narrow win for Labor (see Appendix C).

Figure 11: Opinion polls over

the 45th Parliament

Note: curved lines represent polling averages for each party

and the ‘+’ indicates the 2019 election result for the party.

Source: Compiled by the Parliamentary Library from various

sources.

What is particularly notable about the failure of polling in

the 2019 federal election was not so much that the polls consistently failed to

predict the outcome (although this is significant), but that the polls were so

poor in 2019 after having been so accurate in previous elections.

The Library’s analysis of the polling for the 2016 federal

election noted:

The accuracy of the pollsters has been analysed by a number

of sources, including by polling company ReachTel, who were pleased to report

that it was ‘accurate to less than a single percentage point’ for its TPP

results. In fact, all of the final polls from the major polling companies came

to within one percentage point of the final TPP result, with Essential and

Newspoll coming within 0.1 percentage point of the final result. Newspoll had

each of the major party primary votes to within 0.3 percentage points of their

actual result.[97]

That is, the polls were remarkably accurate in 2016 in

Australia, despite significant failures in other western democracies. The 2016

federal election paper went on to note:

Given the significant failures of polling in recent elections

in other, similar, western democracies (such as the United Kingdom (UK) in 2015

and the United States in 2016), there is a question as to why the national

polling in Australia continues to be so accurate. The increasing number of

households without landlines was thought to undermine the representativeness of

political polling, however, the one Australian polling company that still uses

live phone calls, Ipsos, was substantially less accurate than those who use

robopolling (automated phone calls) and online panels, such as ReachTel and

Newspoll.

It may be that Australia’s compulsory voting is one of the

reasons that polling still works for Australian elections. A review of the

failure of the polls at the 2015 UK general election found that three groups

were underrepresented in the polling: older voters, who predominately voted

Tory; young non-voters, who were polled less frequently than young people who

did intend to vote; and busy voters, who were more likely to vote Tory.

Compulsory voting means that Australian polling has much

firmer grounds for extrapolating from demographic sub-samples. As long as some

older people respond to an online poll, and those people are reasonably representative

of the views of older people, it is not difficult to extrapolate to the wider

voting population with a degree of accuracy. Sophisticated turnout models to

determine which demographics will vote are not necessary. Polling experts also

note that the Telemarketing and Research Industry Standard, which allows

polling companies to contact numbers on the Do Not Call Register if the polling

is for research purposes, also adds to the accuracy of Australian polling. [98]

The major factors that existed in 2016 essentially

continued relatively unchanged in 2019: a trend away from fixed phone lines to

mobile phones; lack of a phone directory mapping mobile phone numbers to

geographical addresses; and compulsory voting and high levels of turnout. Any

analysis of the 2019 polling failure should be viewed within this wider

context.

It has been noted that while seat-level polling continues

to be highly unreliable, and similar failures in state election polls have

occurred recently, the amount of polling at the federal level in the lead-up to

an election tends to smooth over any inconsistencies between single polls when

the entirety of the polling is aggregated.[99]

As such, the failure in 2019 was essentially unprecedented.

One political scientist has argued that the polling

suggesting that Labor would win likely affected the style of campaigns run by

Labor and the Coalition, which as a result may have affected the outcome of the

election.[100]

A number of theories have been proposed as to why the

polls may have failed so notably in 2019, but as yet there is little evidence

to promote one theory over another. The theories that have been advanced for

the failure include:

- herding, where polling companies deliberately or inadvertently

adjust their results to be more consistent with other polling results (either

their own previous polls or the polls of other polling companies)[101]

- reluctance of polled voters to tell pollsters that they planned

to vote for the Coalition (referred to as the ‘shy Tory’ effect in the UK)[102]

- a late swing to the Coalition, not captured by any of the polls (however

at least one polling expert’s view is that all the evidence suggests that there

was no such late swing)[103]

-

voters deciding late, who had told pollsters they ‘don’t know’

who they were voting for, favouring the Coalition[104]

and

-

poor sampling procedure that systematically missed some voters

who prefer the Coalition.[105]

The Australian Market and Social Research Organisation

(AMSRO), a peak body for social research companies, announced an inquiry into

the polling failure.[106]

However it has been noted that of the pollsters who published national polls

for the 2019 federal election, only Ipsos appears to be a member of AMSRO,[107]

and the media organisations that had commissioned Ipsos’ polling have ended the

relationship after the 2019 federal election.[108]

In a statement YouGov, which owns Galaxy and conducts

Newspoll, stated that it would submit a written statement to the inquiry, but

that as ‘the polling conducted under our brand YouGov Galaxy during the federal

election was commissioned by paid clients it is not appropriate to provide raw

data from these polls retrospectively to third parties’.[109]

AMSRO released an interim discussion paper on 20 May 2020

for consultation,[110]

focusing on methodological transparency, rather than offering a view as to what

went wrong in 2019.[111]

A complicating factor for examining the cause of the polling

failure is the lack of transparency in the ways in which polling is conducted

in Australia. One long-time polling expert has noted that many Australian polls

do publish their sample size and the dates on which the polling is conducted,

but do not publish the sampling variance of the poll, and some do not publish

the questions that were asked.[112]

In conducting a poll a polling company will typically identify

a number of parties and ask the respondent which of those, or ‘other’, would

receive their first preference. If the answer is ‘other’ then a list of minor

parties may be read out. Analysts have noted that including a minor party in

the first list tends to elevate the numbers of respondents who chose that

party. Changes in the parties that are part of that list over time leads to

difficulties in comparing results over time, particularly if a polling company

is not transparent about the changes. Pollsters can also be inconsistent and

non-transparent about how they treat the respondents who report they do not

know who they are voting for.[113]

Even the questions of who owns a polling company and the interests of the

owners, and who has paid for a particular poll, are often unclear.[114]

Another polling analyst has reported that while Galaxy, which

produces Newspoll, used online methods and robopolls, it was not known what

proportion of each sampling approach was used to produce the outcome.[115]

Other Australian pollsters use a variety of measures for contacting respondents:

The four active pollsters at this election were YouGov

Galaxy, which conducts Newspoll, Ipsos, Essential and Morgan. Galaxy uses

online methods and robopolling, Essential uses online methods, Ipsos uses live

phone polling and Morgan uses face-to-face interviews. No pollster does only

landline polling – Ipsos calls mobiles.[116]

In September 2019 YouGov announced that it would be

adjusting its polling procedure in the wake of the 2019 federal election opinion

polling failure and that it supported the creation of an Australian Polling

Council, along similar lines to the British Polling Council. YouGov stated that

it was ‘supportive of a common goal of greater transparency and ongoing public

confidence’.[117]

In April 2020 YouGov announced the creation of the Australian Polling Council,

with Essential and UComms as members. The three members constitute the majority

of political opinion polling in Australia. The statement said:

The objectives of the Council are to adhere

to a strict set of guidelines intended to:

◦ Ensure

standards of disclosure that provide an adequate basis for judging the

reliability and validity of the results of survey results that are published in

media

◦ Encourage

the highest professional standards in public opinion polling and advance the

understanding of how polls are conducted and how to interpret poll results

◦ Inform media

and the public about best practice in the conduct and reporting of polls

Inspired by similar organisations in the US

and Great Britain; YouGov, Essential and UComms believe that the future of

Australian polling should operate with guidelines informed by a deep

understanding of the market and the complexities of the local landscape.

These guidelines aim to provide an

appropriate balance between responsible disclosure to the public, the needs of

media outlets, and the intellectual property rights of the polling companies.

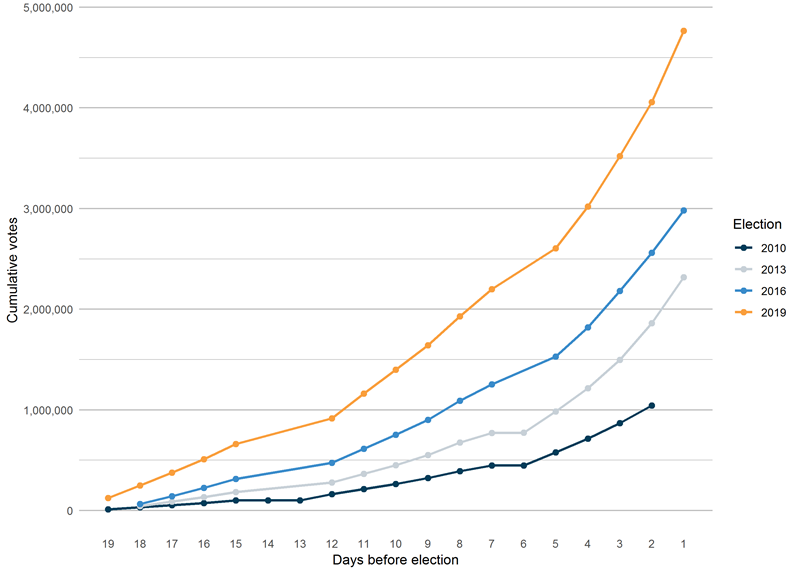

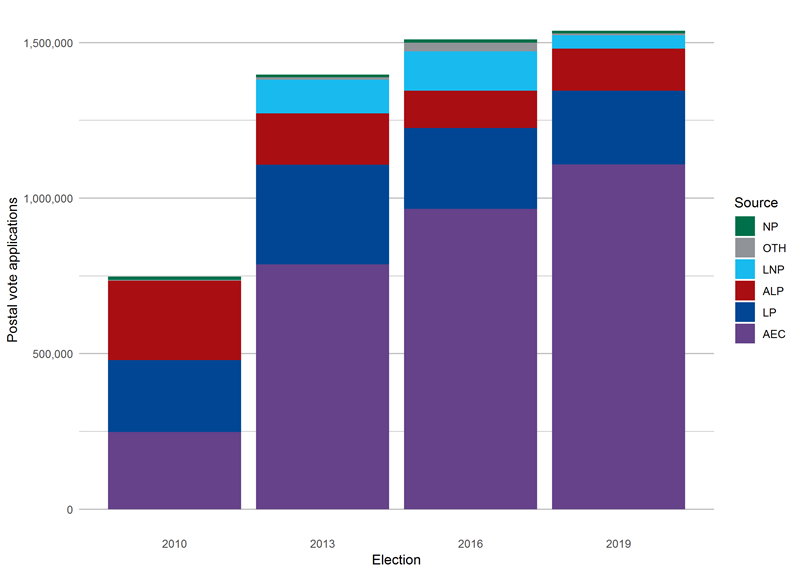

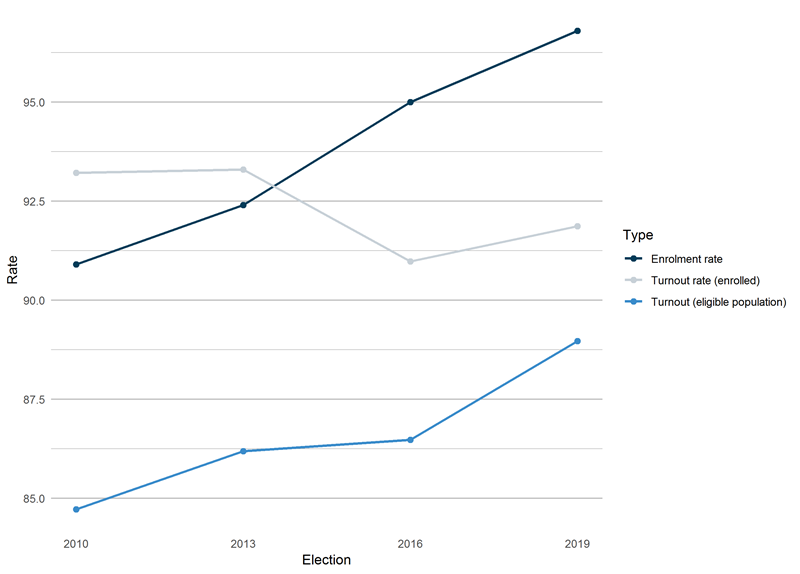

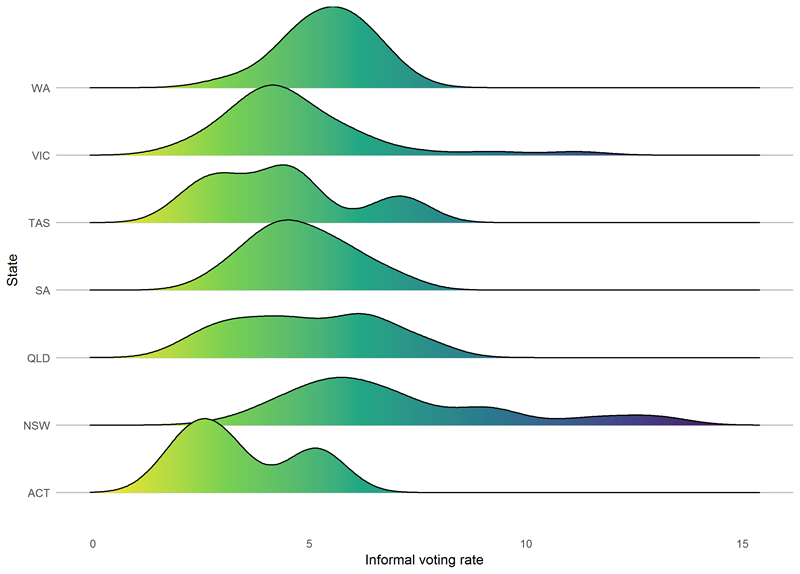

Active polling companies in the industry are invited to join in to