Budget Review October 2022–23 Index

Dr Angela Clare

The October

2022 aid budget increases Australia’s development assistance to the region

by $1.43 billion

over the next 4 years, driven by growing security concerns and development needs

in the region.

Australia’s official development assistance (ODA, or aid)

for 2022–23 now totals $4,651.1 million, an increase of $102 million

on the March

2022 budget estimate ($4,549 million).

The bulk of the extra funding falls in the following 3 years

(2023–24, 2024–25 and 2025–26), which see an average

gain of $440 million on previous estimates. Table 1 shows forward

estimates in nominal prices.

Table 1 Official development

assistance, 2021–20 to 2025–26, nominal prices

| $ million |

2021–20 |

Oct 2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

2025–26 |

| Expenditure |

4,457(a) |

4,651(b) |

4,768(c) |

4,784(c) |

4,871(c) |

(a) Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

(DFAT), ODA Budget Summary 2022–23 (March 2022)

(b) DFAT, ODA Budget Summary October 2022–23 (October 2022)

(c) Australian Council for

International Development, October 2022–23 Supplementary Federal Budget

The COVID-19-related temporary measures introduced by the

Morrison Government over the last 3 years have been folded into the aid budget

‘base’, making these increases permanent.

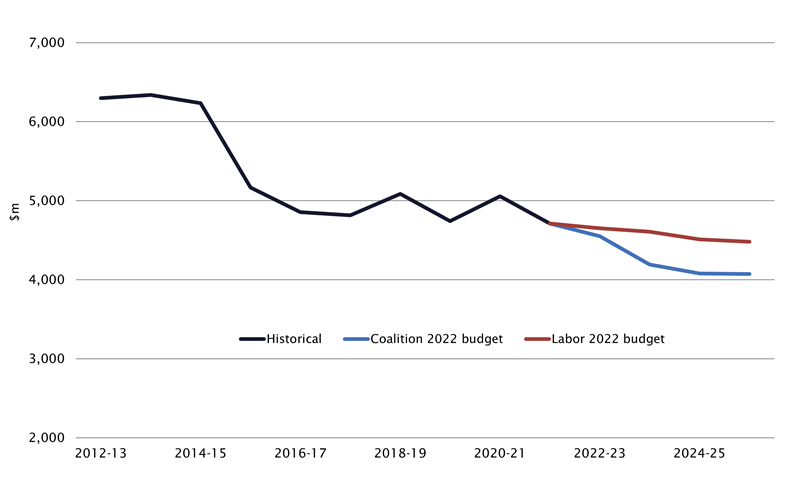

Despite the increases, ANU

Development Policy Centre analysis suggests

that aid will continue to fall in real terms across the forward estimates,

decreasing by 5% by 2025–26 when adjusted for inflation. Figure 1 compares

aid adjusted for inflation under the previous and current governments.

Figure

1 Aid adjusted for inflation under the Coalition and Labor

Source: ANU Development Policy Centre

The October 2022 Budget sees no

change in Australia’s ODA to gross national income (GNI) ratio, which is

estimated to remain at 0.20% in 2022–23, well below the current OECD

Development Assistance Committee (DAC) average

of 0.33%.

Australia ranks 21 out of

29 OECD DAC countries on generosity of ODA programs, despite being the ninth

largest economy in the group.

Specific measures

The additional $1.43 billion in development assistance

over the forward estimates (details of which can be found in Budget measures: budget paper no. 2:

October 2022–23, pages 110–115) includes:

- $900 million to the Pacific and Timor-Leste (up from the

$525 million pre-election commitment)

- $470 million for Southeast Asia (no change from pre-election

commitments)

- $30 million for the Australian NGO Cooperation Program (no

change from pre-election commitments)

- $26.6 million in additional departmental resourcing for DFAT

program administration.

Pacific

Australia’s increased aid to Pacific Island countries –

estimated to total a record high of $1.9 billion in 2022–23 – aims

to ensure that ‘we remain a partner of choice for the countries of our

region and responsive to Pacific priorities’ (p. 1).

The Government identifies support for action on climate change

and COVID-19 recovery among its priorities in the region. This includes

‘supporting Pacific economies to grow, unlock opportunities and boost

connectivity to priority sectors’, providing direct budget support to Pacific

Island countries to ensure the delivery of essential government services such

as health, water and sanitation, education and investing in women and girls,

which ‘has a powerful effect on economic growth and wellbeing’.

While a detailed breakdown of how the new funding will be allocated

has not yet been provided, $75 million has been directed through bilateral

programs, with Kiribati (up by 32%) and Samoa (up by 22%) receiving the largest

increases. Regional programs will increase by 39%, or $212 million.

Specific measures include:

-

$500 million to increase grants for infrastructure in the

Pacific and Timor-Leste, a doubling of grant funding under the Australian

Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP). The AIFFP now totals

$4 billion: $1 billion in grants and $3 billion in loans. The

additional funding is over 10 years and will be met from the existing ODA

program (p.

110). It includes:

-

$50 million from existing funds to establish a Pacific Climate

Infrastructure Financing Partnership

-

$25 million in additional funding over 4 years to DFAT to

administer the facility.

The Government has also announced a number of non-ODA initiatives

to support ‘security and engagement priorities’ in the region. These are largely

funded through existing resources and include:

-

$67.5 million over 4 years (and $12.4 million per year

ongoing) to enhance the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility Scheme (p.

111)

-

a new Pacific Engagement Visa, allowing up to 3,000 nationals of

Pacific Island countries and Timor-Leste to permanently migrate to Australia

each year (p.

150)

-

Pacific Security and Engagement Initiatives (pp.

114–115):

-

$45.7 million over 2 years to support Australian Federal Police

deployment in Honiara through Solomon Islands’ International Assistance Force

-

$6.9 million to establish an Australia-Pacific Defence School

-

$30.4 million over 4 years (and $14.5 million ongoing) to upgrade

aerial surveillance capability under the Pacific Maritime Security Program

-

$22.3 million (and $6.4 million ongoing) to establish a

network of Australian Border Force officers across the Pacific

-

$32 million over 4 years for the ABC to expand its content and

transmission in the region.

Southeast Asia

In line with its pre-election pledge to deepen Australia’s

engagement with Southeast Asia, the Government has pledged an additional

$470 million in aid to the region over the next 4 years. DFAT’s aid

budget summary notes that this funding will ‘support sustainable economic

growth that enables the active participation of women and invests in human

capacity and resilience’, and that Australia will help countries in the region

transition to net-zero emissions.

Myanmar will increase to $120.6 million (up 22%),

Vietnam to $92.8 million (up 17.5%) and Cambodia to $12.9 million (up

19%). Regional programs will increase by $117.8 million to $372.5 million.

Specific initiatives for the region include:

-

$200 million for a Climate and Infrastructure Partnership

with Indonesia, focusing on climate and infrastructure financing, disaster

mitigation and renewable energy

-

$9 million (non-ODA) to appoint a Special Envoy to Southeast

Asia and establish a new Southeast Asia office in DFAT

-

$4 million (non-ODA) to establish a pilot in-country

language skills program in Vietnam.

The Government has also committed to supporting a regional

order with ASEAN at its centre, and deepening Australia’s regional economic

and security cooperation through the ASEAN-Australia Comprehensive Strategic

Partnership.

Other foreign policy measures

-

$2 million over 2 years has been allocated to develop a

First Nations Foreign Policy and to establish an Office of First Nations

Engagement, headed by an Ambassador for First Nations People (p.

112)

-

$2.2 million has been allocated for Memorial Services for the

Bali Bombings Travel Assistance Fund (p.

114).

Drivers of change

The boost to the

aid program comes as global threats to security and development continue

to escalate. According to the United Nations, the number of people affected by

hunger has more than

doubled in the past 3 years. Commenting on the recent release of its Poverty

and shared prosperity report, World Bank President David

Malpass noted:

Of concern to our mission is the rise in extreme poverty and

decline of shared prosperity brought by inflation, currency depreciations, and

broader overlapping crises facing development. It means a grim outlook for

billions of people globally.

DFAT’s October 2022 aid

budget summary notes that

in a region where ‘22 of our 26 nearest neighbours are developing countries’,

Australia will ‘play its part in supporting sustainable development’ and

address the ‘shared challenges’ of ‘climate change, COVID-19 recovery and

deteriorating global economic conditions’. It also notes:

For the first time in 20 years, the

number of people living in extreme poverty has increased. Women and girls have

been impacted most, with almost half a billion now living below the poverty

line. Global food insecurity means over 800 million people go to bed hungry

each night. (p. 1)

Growing instability in the region is also driving increased

investment in Australia’s aid program. Announcing the Government’s increased assistance to the region, the Foreign Minister was reported to have stated:

… Without these investments, others will continue to fill the

vacuum and Australia will continue to lose ground ...

Our assistance will help our regional partners become more

economically resilient, develop critical infrastructure and provide their own

security so they have less need to call on others.

New aid policy

On 14 October 2022 the Albanese Government called

for submissions on the design of a new international development policy, to

set the long-term direction of Australia’s aid program. The new aid strategy will replace the 2-year interim aid strategy, Partnerships

for recovery, developed under the Morrison Government as a response to

the COVID-19 crisis in 2020.

The Albanese Government has also asked DFAT to conduct a review

into new forms of development finance for Australia, to ‘support Australia’s

foreign policy, trade, security and development objectives and help countries

in our region achieve their development and climate objectives’.

Commentary

In the context of growing strategic competition in the region,

Pacific expert Joanne

Wallis has argued that increased spending was ‘not the only answer’ for

Australia to improve relationships with the region, and ‘a lot will depend on

how the increased funding is spent’. Wallis suggests that ‘so far, the ALP

government has struck a positive tone in their public statements about the

Pacific and indicated a willingness to listen and respond to the Pacific’.

The boost to the aid budget has been welcomed

by the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID), which has

been concerned about the prospect of a fall in the aid budget as temporary

COVID-19 measures come to an end in the next 2 years. ACFID has also welcomed the

Government’s renewed focus on gender equality across the aid program, but

called for this focus to translate into increased funding in the next Budget.

Some aid groups have strongly criticised the Government’s failure

to increase the humanitarian budget in the face of ‘multiple

global crises’ and have called for the Government to ‘broaden

its focus on aid beyond the Pacific’. Help Fight Famine Australia has urged

the Government to provide $150 million to address the urgent food crisis

unfolding in Somalia, Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria and the Horn of Africa, in addition

to the $15 million it has provided to date.

Some groups have also queried

the development value of increases to the Australian Infrastructure

Financing Facility for the Pacific (AIFFP), with ACFID concerned that ‘the

Government is locking in significant funding from a limited ODA budget to a

Facility which has a largely geostrategic rationale and has minimal proven

development impact’ (p. 21). In particular, ACFID is concerned that

without increasing funding for ‘social infrastructure to support inclusive and

equitable economic recovery’, Australia risks compounding Pacific debt burdens

and compromising governments’ abilities to fund essential services.

ACFID also expressed its disappointment that AIFFP

climate-related investments will be fully or partially counted towards

Australia’s $2 billion

climate finance commitment, ‘given that the most significant climate needs

in the Pacific are for adaptation, which AIFFP lending is unlikely to be able

to fulfill’ (p. 21).

All online articles accessed October 2022

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.