Budget Review 2022–23 Index

James Haughton

The Budget Review articles on Indigenous Affairs summarise

and contextualise Indigenous-specific measures across portfolios. This article covers

measures related to leadership, land, economic development and education, while

a

separate Indigenous affairs article covers measures relating to health,

culture and language, housing, justice and safety. These categories have been

chosen to align with the Budget and elements of the new Closing

the Gap Priority Reforms and Targets.

Unless otherwise stated, all page references are to Budget

measures: budget paper no. 2: 2022–23.

Overview of budget trends

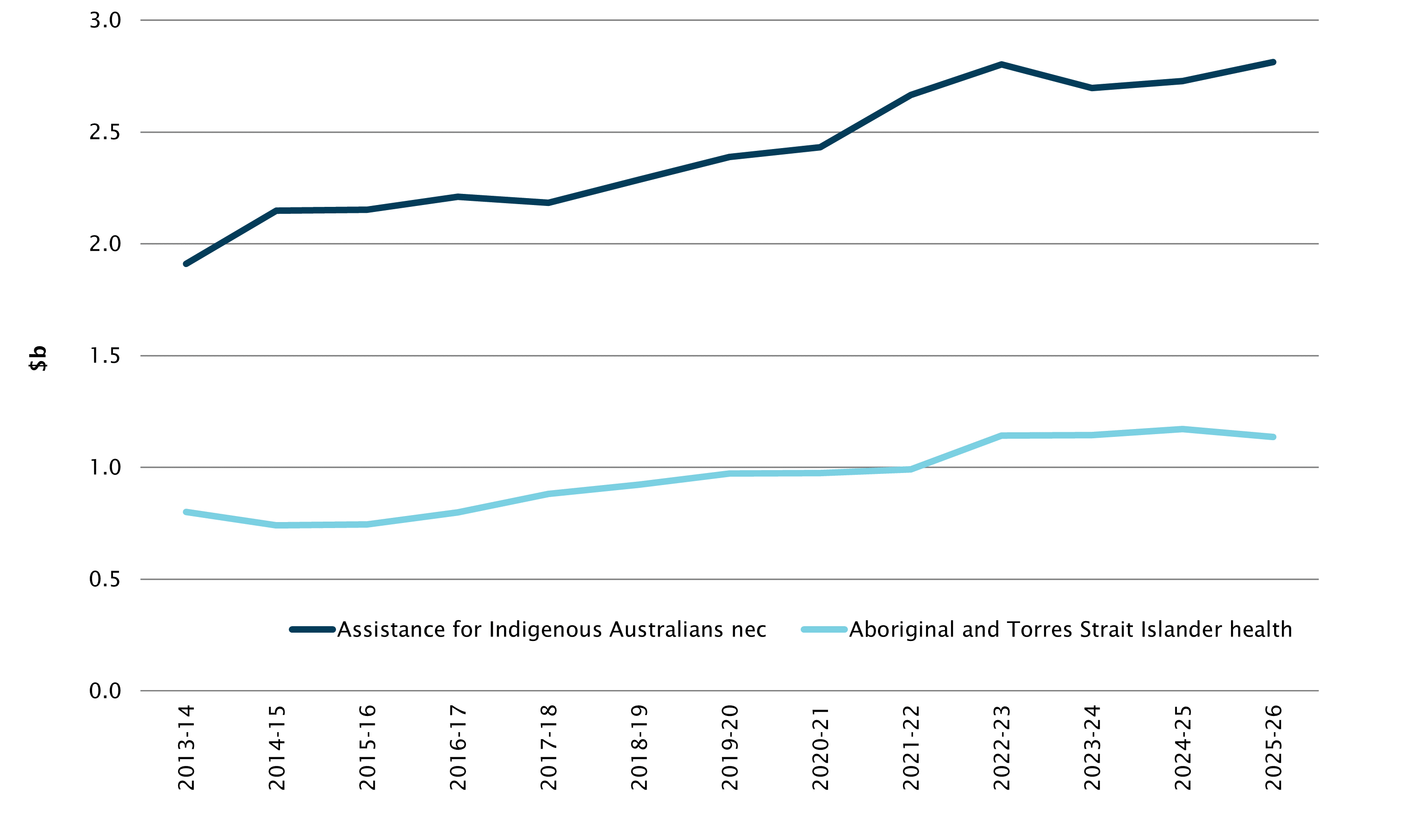

The 2022–23 Budget continues an apparent trend of increasing expenditure on

Indigenous-specific Commonwealth programs under the Morrison government, after constant

or slowly increasing expenditure levels under the Abbott and Turnbull

governments. This is in part driven by the temporary response to COVID-19, but

is also due to increased Commonwealth investment under the new Closing the Gap

framework, particularly measures announced on

5 August 2021 with the release of the Commonwealth’s

Closing the Gap Implementation Plan. The trend in the budget function

‘Assistance for Indigenous Australians nec [not

elsewhere classified]’ (Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper no. 1 2022–23, pp. 154, 158)

is shown in Figure 1. This figure includes programs delivered by the National

Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) under the Indigenous Advancement Strategy

(IAS), expenditure by Indigenous-specific government corporate entities such as

Indigenous Business Australia, the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation and the

Torres Strait Regional Authority (excluding inter-agency transfers), as well as

a number of National Partnership payments. Expenditure against this function has

consistently increased over the last 3 budgets, as has the budget function for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2022–23, pp. 151, 154).

However, these increases are partly offset by the Commonwealth’s withdrawal

from funding Indigenous-specific housing (not included in these aggregates).

Source: Prepared by the

Parliamentary Library from previous budget papers. Figures are nominal (non-inflation

adjusted) dollars reflecting actual spending in that year except for those from

2022–23 onwards, which are projections from current Budget Paper 1.

Expenditure on these Indigenous programs is currently

projected to flatten over the forward estimates, reflecting the projected end

of the National Partnership on Northern Territory Remote Aboriginal Investment

(NTRAI). However, the recent

announcement of a 2-year extension of the NTRAI indicated that other investments

in remote Northern Territory communities would take its place, suggesting that

this flattening may be more apparent than real.

Leadership and governance

The Budget includes several measures intended to strengthen Indigenous

leadership, decision-making power and capacity. These are in line with the Closing

the Gap Priority Reforms to boost shared decision-making and strengthen

community-controlled organisations.

$31.8 million is provided in 2022–23 in the Indigenous

Voice – Local and Regional Voice Implementation measure to ‘commence establishment

of 35 Local and Regional Voice bodies’ (p. 161) in line with an option

presented by the Indigenous

Voice Co-design Process Final Report. The Minister’s

media release announcing this response states, ‘for the Indigenous Voice to

work, it must have a strong foundation from the ground up’, presumably

explaining why no funding or framework has yet been announced for a National

Voice. Having 35 regions would correspond to the number of former

ATSIC regions, which are still the basis for the Australian

Bureau of Statistics’ Indigenous statistical geography.

$3.0 million will be provided over 2 years from 2021–22 to

support Aboriginal Peak Organisations Northern Territory (APONT) to work with

the Australian Government and Indigenous Australians to develop a strategy for

future investment in the Northern Territory (p. 156). This is in line with a NTRAI

review recommendation (p. 9) that ‘future arrangements should provide

Aboriginal representatives a role as shared decision-maker in the design,

delivery and monitoring of policies and programs which are delivered to their

communities’. Funding for this measure has already been provided.

$37.5 million is provided over 5 years for the Future of

Prescribed Bodies Corporate measure to build the capacity of the Registered

Native Title Prescribed Bodies Corporate (RNTBCs) sector (p. 160), of which

$6.6 million is new money and the remainder is to be met from the IAS budget. Increased

funding and capacity-building for RNTBCs has been frequently called for by the

sector, particularly in response to legislative changes affecting RNTBCs such

as those proposed for the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander) Act 2006 in a

recent review, or those introduced by the Native Title

Legislation Amendment Act 2021 (Bills

Digest). The Senate

Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee inquiry into that Bill received

numerous submissions about the lack of resources for building governance capacity

faced by the sector (Committee

report, pp. 46–47).

Also likely related to these calls and reports is the $21.9

million measure Strengthening Indigenous Leadership and Governance (p.

165, see also the Government’s media

release) which provides $13.5 million for the Australian Indigenous Mentoring

Experience (AIME); $6.7 million for the Office of the Registrar of

Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) to develop governance training materials for

Indigenous organisations; and $1.7 million to the NIAA to provide scholarships

for Indigenous Australians to undertake company directors’ courses, and

monitoring and evaluation.

The National Native Title

Council welcomed the increase in RNTBC capacity building funding, but

expressed disappointment that there was no ongoing secure funding for the

sector. The native title sector is also likely to be disappointed that the

government has not acted further on reforms to the Native Title Act 1993

and RNTBCs suggested by the Australian

Law Reform Commission or the Taxation of

Native Title and Traditional Owner Benefits and Governance Working Group Report

to Government, which would strengthen not only the governance but also

the bargaining and financial position of RNTBCs.

Land

The centrepiece of the Indigenous budget is the Indigenous

Rangers – Capacity building measure (p. 161), which provides $636.4 million

over 6 years (of which $322.4 million is over the current forward estimates) to

expand the Indigenous Rangers program. The measure promises to fund up to 1,089

new full-time equivalent (FTE) ranger positions and 88 new ranger groups,

expand women and youth rangers programs, and set up an Indigenous Land and

Water Management body. The Indigenous Rangers program currently has a budget of

$102 million annually (with ongoing funding of this amount announced

in March 2020) and employs

898.7 FTE positions (at 9 April 2021) consisting of over 2,100 full-time,

part-time and casual rangers. This new funding roughly doubles the existing

funding per year, meeting longstanding calls

from stakeholder group Country Needs People and matching a commitment

by the Australian Labor Party. As well as positive

outcomes for employment and the environment, a recent

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW report) found Indigenous Ranger programs promote Indigenous

mental health and reduce suicide risk, a priority

of the Morrison government.

Measures to improve the governance of native title-holding

Prescribed Bodies Corporate are noted above. As RNTBCs currently hold some form

of native title over 3,321,982

square kilometres, or approximately 43.1% of Australia’s land area, their

capacity for effective governance is a key element of land management.

The Budget also announces $74.4 million over 9 years,

already provided for, for partnerships with Traditional Owners in the Great

Barrier Reef (p. 57) and a package of $26.8 million, of which $16.2 million is

new money, under the Supporting the Management of Commonwealth National

Parks measure (p. 57). Most mainland Commonwealth

National Parks are owned by Traditional Owners and rented by Parks

Australia. The package includes $10.6 million to increase Traditional Owner

engagement, employment and traditional knowledge conservation. This measure was

announced

on 9 March 2022 in response to a

critical report finding that Parks Australia had lost the trust of

Traditional Owners.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea

Future Fund (ATSILSFF), which provides funding to the Indigenous Land and Sea

Corporation to acquire land and water for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people, has had another good year. For the year ending 31 December 2021, the

ATSILSFF achieved a return of 10.7% against a benchmark of 5.5%. The total

capital of the ATSILSFF was valued at $2.2 billion at the end of that year (Budget

paper no. 1, p. 331).

Economic development and employment

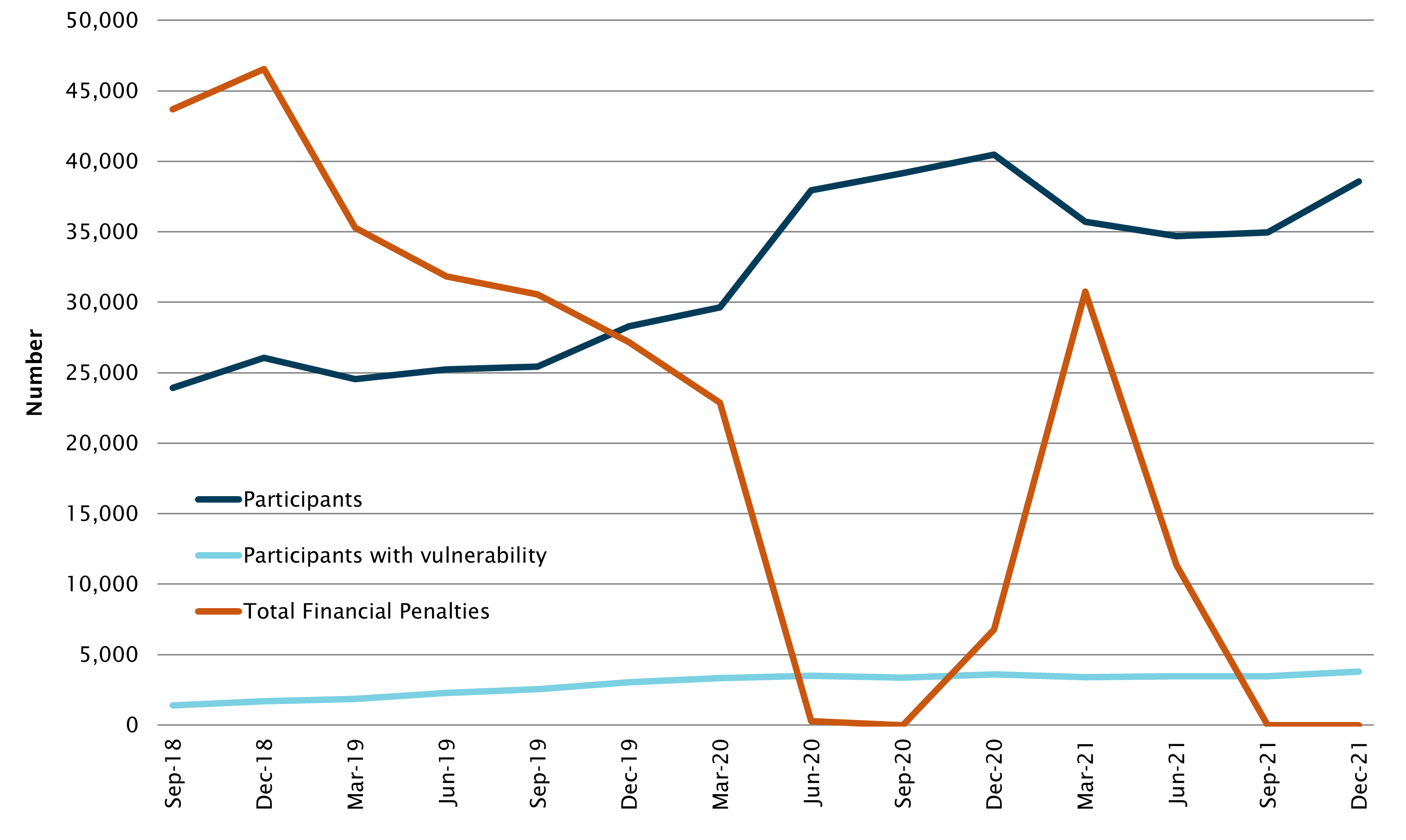

Aside from the Rangers measure, the major employment-related

measure in the Indigenous budget is further supplementary funding of $98

million in 2022–23 for Community Development Program (CDP) providers to meet

increased demand (p. 156). CDP

participant statistics for the COVID-19 pandemic period have recently been

released (see Table 1 and Figure 2 below). These show a significant increase in

participant numbers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting changes

in Jobseeker payments and CDP penalty regimes. Also notable is the rapid

drop in participant numbers when financial penalties for non-participation in

CDP activities were re-imposed in early 2021, until penalties were

again removed on 12 May 2021.

Table 1 Summary of data on

CDP participation and financial penalties

| CDP Quarter ending |

Participants |

Participants w vulnerability |

Total Financial Penalties (n) |

| Sep-18 |

23,929 |

1,411 (6%) |

43,680 |

| Dec-18 |

26,058 |

1,691 (6%) |

46,544 |

| Mar-19 |

24,542 |

1,852 (8%) |

35,282 |

| Jun-19 |

25,251 |

2,270 (9%) |

31,821 |

| Sep-19 |

25,431 |

2,539 (10%) |

30,544 |

| Dec-19 |

28,299 |

3,030 (11%) |

27,181 |

| Mar-20 |

29,638 |

3,338 (11%) |

22,872 |

| June-20 |

37,958 |

3,509 (9%) |

266 |

| Sep-20 |

39,166 |

3,376 (9%) |

0 |

| Dec-20 |

40,469 |

3,581 (9%) |

6,783 |

| Mar-21 |

35,718 |

3,392 (9%) |

30,764 |

| June-21 |

34,681 |

3,459 (10%) |

11,361 |

| Sep-21 |

34,964 |

3,477 (10%) |

np |

| Dec-21 |

38,565 |

3,785 (10%) |

np |

Source: NIAA, Community Development Program Quarterly Compliance Data. Some data is not published (np) but appears to be

below 20

Figure 2 CDP participants and financial penalties over time

Source: NIAA, Community Development Program Quarterly Compliance Data. Some data is not published (np) but appears to be

below 20.

In a related measure, the Remote Engagement Program

measure (p. 164) provides $11.5 million over 5 years from 2021–22, of which

$4.7 million is new money and the remainder is from the IAS budget, to continue

piloting the Remote Engagement Program (formerly the Remote

Jobs Program), which will replace the CDP on 1 July 2024. This measure also

provides funding for legal fees and grants agreed by the Commonwealth as a

result of the CDP

Class Action settlement.

The measure McDonald v Commonwealth class action –

discovery costs (p. 162) provides a non-published amount for discovery

processes associated with a

stolen wages class action brought by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

who lived and worked in the Northern Territory between 1 June 1933 and 12

November 1971 and had their wages withheld. Potential Commonwealth

responsibility for stolen wages in the Northern Territory was previously raised

in the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs 2006

report, Unfinished

business: Indigenous stolen wages, which recommended a research and

discovery process and compensation scheme. However, this proactive approach was

rejected

in 2010 by the Rudd government.

$3.2 million is allocated in 2022–23 to extend the Time to Work

Employment Services program for 12 months to provide continued

in-person pre-employment services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

prisoners (p. 74).

Given the relatively high proportion of the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander population in remote, regional and northern Australia,

government investment in regional telecommunications (p. 134), Northern

Territory roads (p. 138) and the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (p.

149) may also create economic opportunities and benefits for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander communities.

Education

There are few Indigenous-specific education measures in the

Budget. The previous National Partnership for Universal Access to Early

Childhood Education, which had Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander preschool

children as a particular focus, has been replaced with a new Preschool

Reform Agreement with a continued focus on Indigenous and disadvantaged

children (Budget

paper no. 3, p. 41). The agreement

includes performance bonuses for the states and territories for lifting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child enrolment and participation.

Other Indigenous-specific measures focus on education in the

Northern Territory. $58.6 million over 2 years will be provided to continue the

Children and Schooling component of the NTRAI (Budget

paper no. 3, p. 42). In addition, the current policy focus of

supporting boarding schools for Indigenous secondary students in the Northern Territory

continues under the School Education Support measure (pp. 77–78), with $29.4

million to extend the Indigenous Boarding Schools Grants program for 1 year and

establish a Commonwealth Regional Scholarship Program to assist families with

the costs of boarding. $6.3 million will also be provided for a new boarding

facility in Tennant Creek, under the Barkly Regional Deal. It is not clear

whether the Regional Scholarship Program is Indigenous-specific.

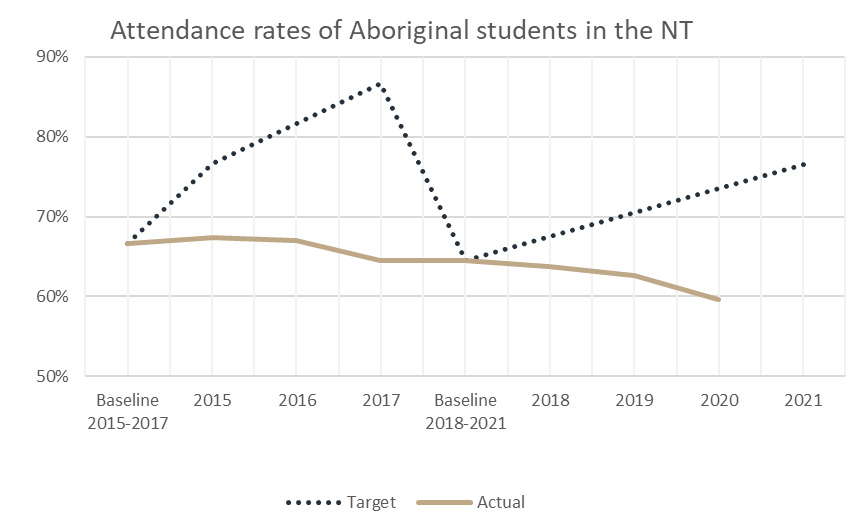

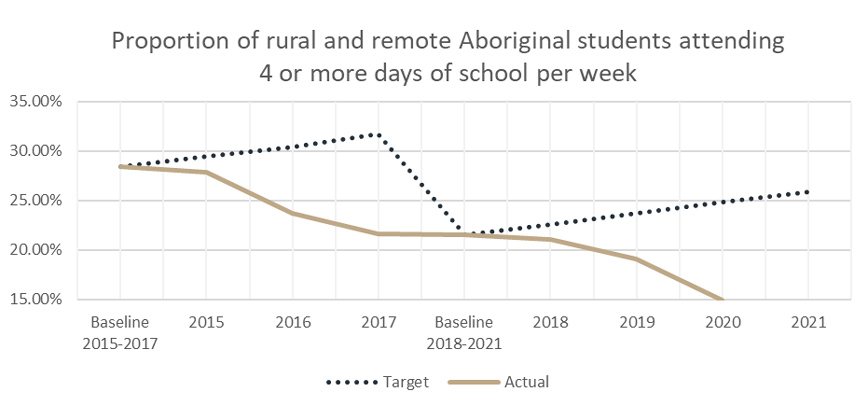

The recently released NTRAI

end-of-term review found that despite improvement in retaining Year 7 boarding-school

students, attendance levels had significantly declined among Aboriginal

students (Figure 3 below) — particularly in remote areas (Figure 4 below) — in

both government and non-government schools, even before the impact of COVID-19

on school attendance.

Figure 3 NT Aboriginal student

attendance rates: target and actual

Figure 4 Rural and remote NT

Aboriginal students attending 4+ days of school per week: target and actual

Source: NIAA, NTRAI End-of-term review, pp. 55-56; separated figures for non-government

schools on p. 107

While the Commonwealth and the NTRAI are not primarily

responsible for school attendance in the Northern Territory, this downward

trend strongly suggests that the policy of supporting boarding school

attendance to improve educational outcomes is not achieving its objective,

particularly as other

studies have directly

linked the boarding school-only policy to high levels of school non-attendance

and dropout among senior students.

Stakeholder reactions

Despite positive reactions to the increase in Indigenous

Rangers and RNTBC

funding, analysts

and stakeholders

have largely criticised the budget for not providing funding sufficient for

structural or transformational change towards closing the gaps in health

outcomes and housing.

All online articles accessed April 2022

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.