Budget Review 2022–23 Index

Dinty Mather

The Australian Government raises money from taxes, custom

duties, revenue from state-owned enterprises, and capital revenues (receipts).

However, when it needs to spend more than it raises it must borrow money and

incur sovereign debt (Australian Government debt).

The mechanism that the Australian Government uses to borrow

money is the issuance of bonds and notes, collectively called Australian

Government Securities (AGS). These are fixed term instruments paying interest

at set intervals, called coupon payments, and finally refunding the face value

after the term has ended, called the principal. Buyers usually include

- resident

investors, such as domestic banks, superannuation funds, domestic hedge funds

and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)

- non–resident

investors including foreign banks, pension funds, foreign hedge funds and foreign

central banks.

Investors can then

trade the AGS among themselves on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX)

commonly called the secondary market.

Types of debt

Statement 6 in Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2022–23 gives the Australian Government’s

current and estimated debt statement. Australian Government debt is expressed

as two debt aggregates:

- gross

debt, which is the face value of AGS on issue at a point of time

- net

debt, which is the market value of AGS on issue less the sum of selected financial assets (cash and deposits, advances

paid and investments loans and placements).

The face value of an AGS is a predetermined amount that the Australian

Government agrees to pay when the term on the AGS expires. Regular interest, or

coupon, payments on each AGS issue may be indexed to inflation in the case of Treasury

Indexed Bonds. Once an AGS has been issued it can be bought and sold on the

secondary market where

the market value is determined by the demand and supply for AGS.

Past and forecasted Australian

Government debt

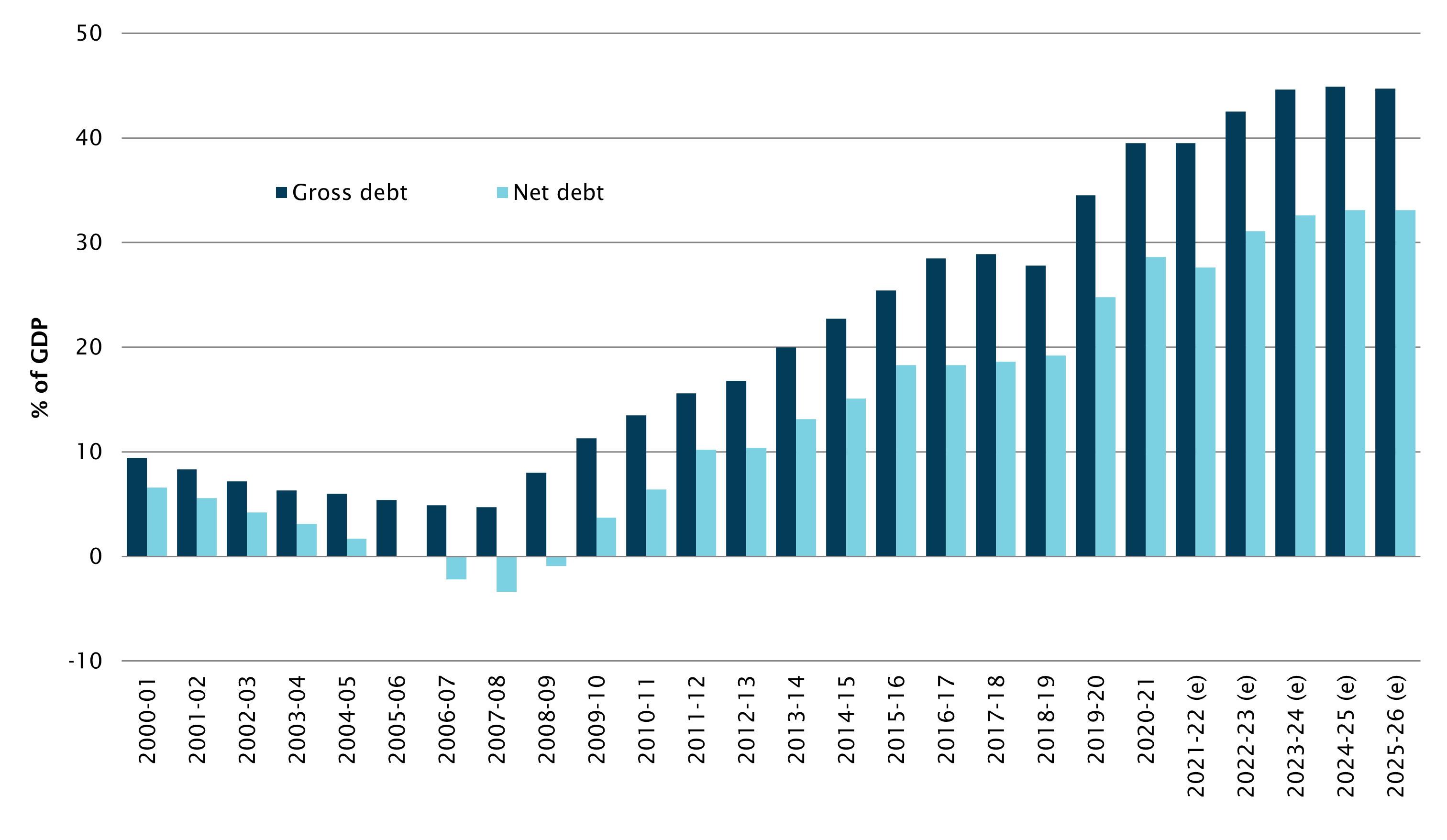

Figure 1 shows gross debt and net debt since 2000–01 with estimates

from Budget

paper no.1 2022–23 (pp. 346–349) for 2021–22 to 2025–26. Due to

improvements in the underlying cash balance, gross debt as a share of gross

domestic product (GDP) is expected to be lower than was forecast at the Mid-Year

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2021–22. Despite this improvement, Budget

paper no.1 2022–23 (p. 349) forecasts that in 2022–23 the value of AGS

on issue will increase in nominal terms by $71.0 billion (3% of GDP) and

by $192.0 billion (2.2% of GDP) between 2022–23 and 2024–25.

Figure 1 Gross debt as a percentage

of GDP and net debt as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Parliamentary Budget Office, Historical

fiscal data; Australian Government, Budget strategy

and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2022–23, Tables 10.4 and 10.5, 346–349.

Although gross debt shows the total AGS liability the

Australian Government holds, net debt incorporates selected government

financial assets and liabilities at fair value and thus provides a broader

measure of the financial obligations of the Australian Government than gross

debt. Table 6.7 in Budget

paper no.1 2022–23 (p. 194) shows that AGS on issue in 2022–23 are

forecast at $1 trillion. The $339.6 billion difference between AGS on

issue and net debt includes:

- $36 billion

in cash and deposits

- $836.6 billion

in advanced paid

- $217 billion

in ‘investments, loans and placements’.

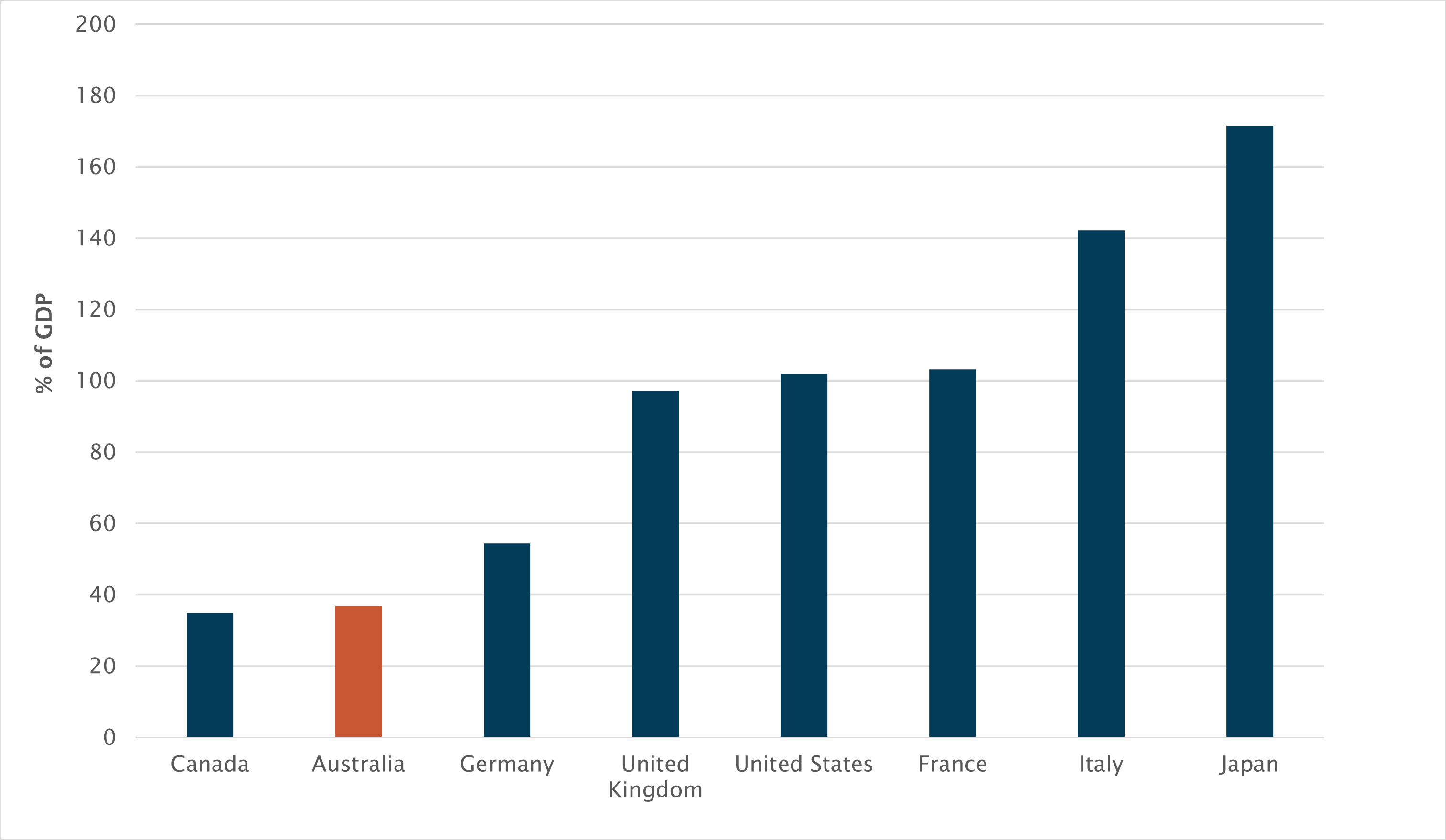

Although the Australian Government has substantially

increased its debt to fund elevated spending during the COVID-19 pandemic, in

comparison to other advanced economies Australia’s net debt burden as a

percentage of GDP is relatively low (see figure 2).

Figure 2 International

comparison of net debt as a percentage of GDP during 2021

Sources: International Monetary Fund, Fiscal

monitor, October 2021: Strengthening the

credibility of public finances, Table 1.2, 5; Australian Government, Federal

fiscal relations: budget paper no. 3: 2022–23, Appendix C, Table C.8, 9 (data for

2020–21).

Because the Australian Government has been increasing debt

since the global financial crisis, the long term capacity to service debt in

terms of paying interest and the principal out of receipts has become a topic

of debate for commentators and the public.

Debt exposure and sustainability

All AGS are denominated in Australian dollars which allows more

control and less risk on the part of the Australian Government than if AGS were,

for example, issued in United States dollars. Non–resident holding of AGS

indicates to some extent an exposure to risk, but because AGS are traded

internationally in the secondary market the ultimate holders are not always

known.

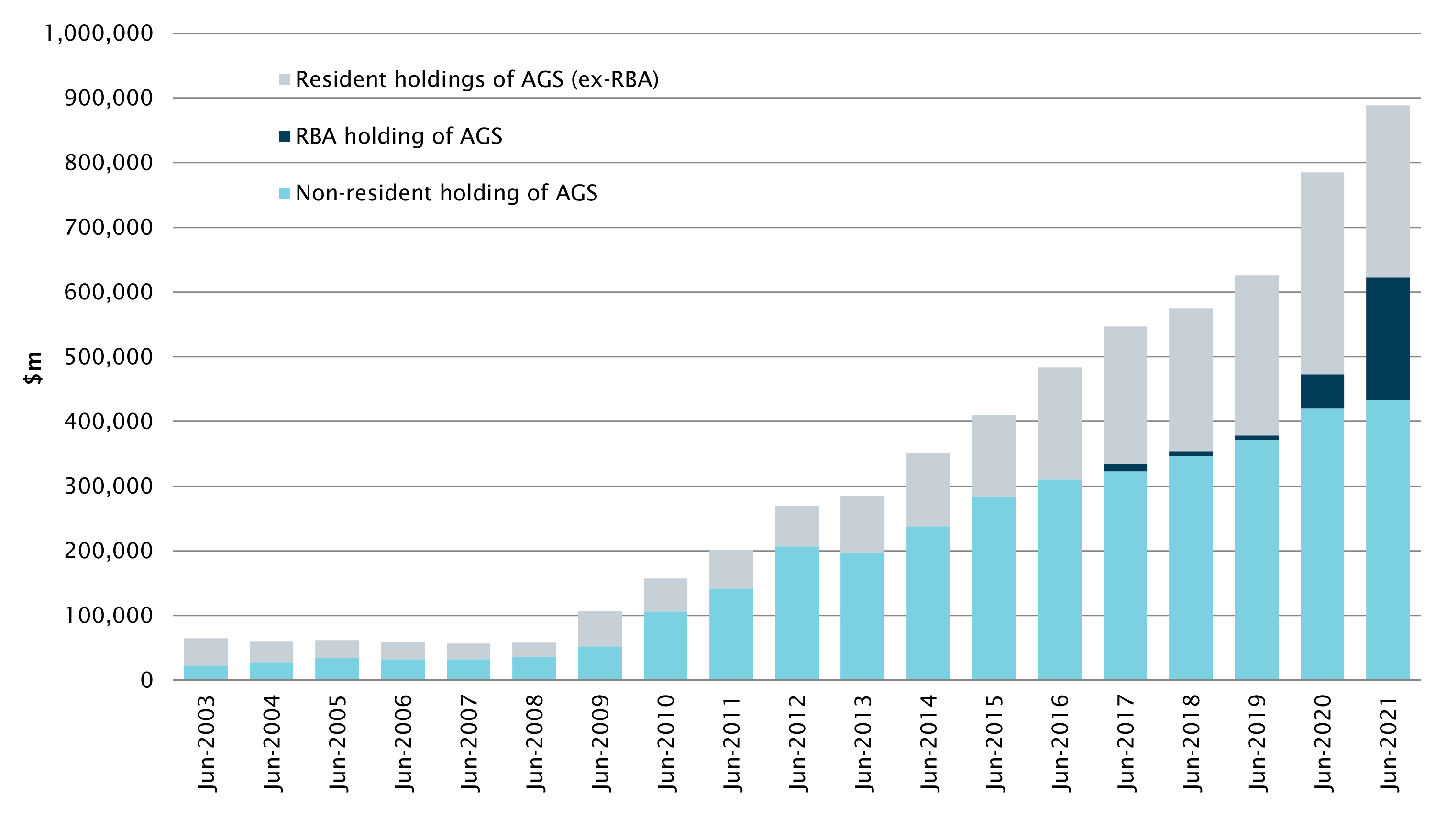

The Australian

Office of Financial Management (January 2020) has provided information on

the AGS investor base. Figure 3 shows the distribution of AGS held by resident

and non–resident investors. Of the $888.4 billion AGS on issue as at 30

June 2021, 49% are non-resident investors, 21% are held by the RBA and 30% are

resident investors.

Figure 3 Debt exposure to resident and non–resident

holders of AGS

Sources: Australian Government, Australian

Office of Financial Management, Data

hub, Non–resident holdings of AGS; Reserve Bank of Australia, Statistical tables, Holding

of Australian Government Securities and semis.

The RBA holds an

increasing portion of AGS and semi-government

securities (semis), which it has bought in the secondary market during the COVID–19

economic disruptions. Noting that the RBA is independent from the Australian Government,

it bought large quantities of AGS and semis in conjunction with using a variety

of other monetary policy tools, designed to increase liquidity and lower interest rates

to stimulate the domestic economy (quantitative

easing), as well as to maintain orderly functioning in the Australian bond

market. The RBA continues to purchase AGS and semis in the secondary market in

efforts to assist a return to full

employment and a target rate of inflation.

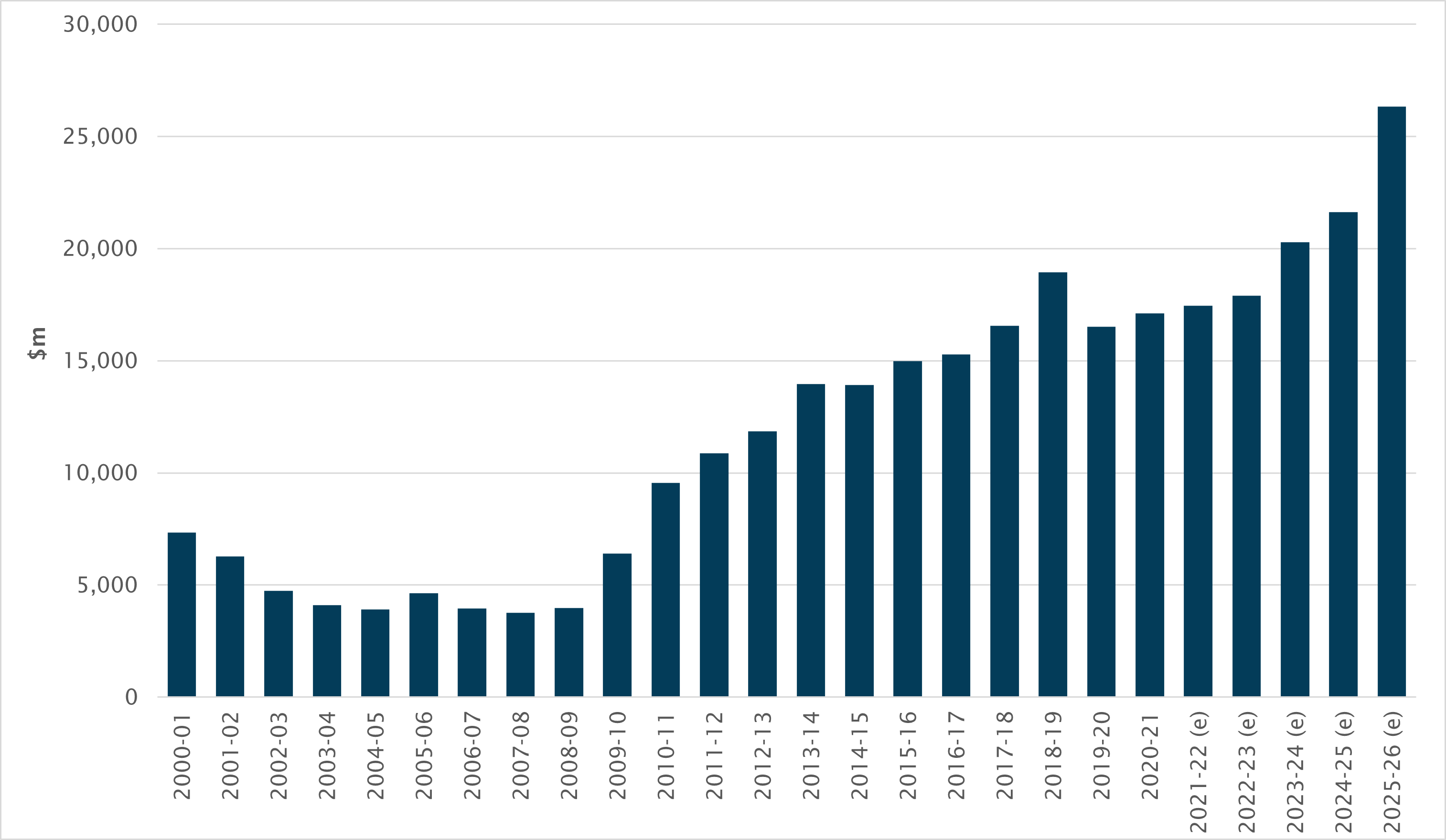

The ability to service gross debt and to reduce it in the

future through taxation and other revenue has become a

concern to many. The question, generally, is whether Australian Government

debt is too big to ensure a safe and sustainable economic future. Figure 4 displays

the past, current and estimated interest cost to the Australian Government of

servicing AGS on issue. Budget

paper no.1 2022–23 (p. 349) shows that the interest cost of servicing

AGS on issue during 2021–22 is about $17.5 billion and is estimated to rise to

$26.3 billion by 2025–26 in nominal terms. The Australian Government can

service the interest paid on AGS by issuing new AGS.

Figure 4 AGS interest cost

Sources: Parliamentary Budget Office, Historical

fiscal data; Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2022–23, Table 10.5, 348–349.

The Parliamentary

Budget Office (PBO) fiscal sustainability research report (April 2021, p. 8)

highlights three main factors that influence the trajectory for gross debt relative

to nominal GDP (debt to GDP ratio) and thus also the ability to service debt without

undue economic stress. These factors are:

- higher

average interest rate on the stock of AGS, in particular new issues and indexed

AGS, will generate higher interest payments on debt

- if

nominal GDP grows and the average interest rate on the stock of AGS grows less

quickly than nominal GDP, the debt to GDP ratio will fall

- a

surplus in the budget balance, which depends on the performance of the economy

and Australian Government policies, means that debt can be paid down leading to

a lower debt to GDP ratio.

The PBO publishes updated forecasts and modelling on the

debt to GDP ratio, among other indicators, in its fiscal projections and

sustainability reporting.

Based on current forecasts in Budget

paper no.1 2022–23 (p. 6) nominal GDP is expected to rise across the

forecast period resulting in a significantly improved underlying cash balance,

which is expected to stabilise debt financing requirements and result in a steady

debt to nominal GDP ratio from 2024–25 onwards. Economic growth, as expressed

in real GDP growth, is also expected to increase in the forecast period which

should contribute towards a lower debt to GDP ratio through the underlying cash

balance.

All online articles accessed April 2022

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.