Budget Review 2021–22 Index

Dr Hazel Ferguson

Funding trends

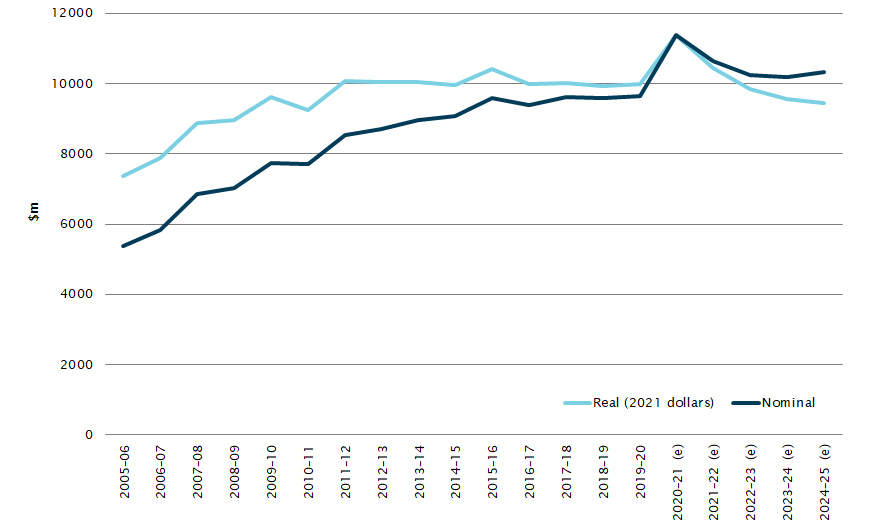

According to Budget

Strategy and Outlook Budget Paper No. 1: 2021–22 (p. 170), higher

education expenditure is expected to decrease by 8.3% in real terms from

2020–21 to 2021–22, and decrease by 9.3% in real terms from 2021–22 to 2024–25.

The initial decrease represents a return to usual funding

levels after the October

2020 Budget added an extra $1.0 billion to university research funding through

the Research

Support Program in 2020–21, in response to COVID-19. The decline after 2021–22

is largely a consequence of the Higher Education

Support Amendment (Job-Ready Graduates and Supporting Regional and Remote

Students) Act 2020, which legislated a reduction in average per-student

funding for domestic Commonwealth supported students.

Parliamentary Library analysis (Figure 1 below) shows that

by 2023–24, real higher education funding (in 2021 dollars) is projected to

return to approximately the same level it was in 2009–10—that is, additional

university places provided through the Job-ready Graduates Package from

2021 are being provided with no overall increase in estimated higher education

funding.

Figure 1:

Australian Government estimated expenditure on higher education, 2005–06 to 2024–25

($ million)

(e) figures are budget

estimates.

Note: real funding has been calculated

by the Parliamentary Library by deflating the nominal expenditure figure by the

June quarter CPI and CPI forecasts from the 2021–22 Budget; this methodology

may differ to that presented in the Budget papers.

Sources: Parliamentary Library

based on Australian Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1:

2021–22; Australian Government, Final

budget outcome, various years.

International education

The most significant question facing higher education in

this Budget relates to the future of international education. International

education is a significant component of most higher education providers’

usual operations, with international students making up 32.4% of all Australian

higher education enrolments in 2019. Uncertainty has characterised the sector

since restrictions were announced for travellers from mainland China on 1

February 2020, then for all foreign nationals (excluding Australian

permanent residents) from 20

March 2020.

According to Budget

Paper No. 1 (p. 36), international student arrivals will continue to be

constrained by quarantine caps until the second half of 2022. Small

numbers of international students are expected to start returning to Australia

from late 2021, with gradual increases from 2022. However, previous plans to

bring international students back to Australia have proven highly subject to

change, with only

one charter flight carrying 63 students having gone ahead so far.

This creates a significant funding challenge for the sector,

with the latest

available data from the Department of Education, Skills and Employment

(DESE), showing revenue from international student fees accounted for approximately

27.3% of university revenue in 2019.

The Mitchell

Institute (p. 3) has estimated that by the end of 2021, the sector will

have lost $13.5 billion due to declining international student numbers,

increasing to a total of $19.8 billion if Australia’s borders remain closed

until the end of 2022. As the pandemic continues, students complete their studies

and are not replaced by new arrivals or comparable numbers of online or offshore

students. The latest

data from DESE shows at March 2021, higher education enrolments by

international students reached 316,441, 12.3% lower than in March 2020.

Commencements reached 61,999 in March 2021 compared with 78,575 in March 2020—a

decline of 21.1%, and 34.1% lower than at March 2019. (Due to travel

restrictions, an enrolment does not confirm that the student is currently in

Australia.)

Although some universities reported budget surpluses for

2020, this is against a backdrop of substantial spending cuts, including

an estimated 17,000 job losses.

While funding uncertainty has the potential to affect all

university operations, research has been regarded as particularly at risk. A

substantial portion of general

university revenue is directed towards research, where international

student fees have been estimated

to account for approximately 27% of spending.

However, despite the hopes of key stakeholders, including Universities

Australia (UA), this Budget contains no new commitments to increased

university research funding beyond the $1.0 billion provided in the October

2020 Budget, or any policy announcements to address the university budget

uncertainty created by continued border closures.

Support package for international

education providers

Budget

Paper No. 1 (pp. 14–15) acknowledges international education is among

the sectors worst hit by the pandemic, but confines its response in this Budget

to English Language Intensive Course for Overseas Students (ELICOS) providers,

as well as non-university higher education providers (NUHEP), which have, on

average, a higher proportion of international students than universities. International

students make up approximately 53.5% of enrolments at NUHEPs, versus 30.6%

of students at universities.

The $53.6 million support package for international

education providers, announced

on 30 April and detailed in Budget

Measures Budget Paper No. 2: 2021–22 (pp. 7–8) chiefly consists of

continuing existing regulatory fee relief for providers, and student loan fee

exemptions. For students, this includes a further extension of the FEE-HELP loan fee

exemption for private higher education providers, although this is reliant on

amendments to the Higher

Education Support Act 2003.

The package also includes a commitment to $26.1 million for

5,000 short-course places through non-university providers, and $9.4 million

for an Innovation Fund, which will allow providers to apply for grants of up to

$150,000 to help them shift to offshore and online delivery.

The short-course funding is intended to encourage local

students to take up places left vacant by declining international student

numbers. It represents a continuation of the Government’s focus on higher

education short courses as a key element of its COVID-19 response.

Short-course funding has also previously been provided for:

These short courses have consisted of newly created Undergraduate

Certificates, as well as Graduate Certificates, which were part of the

qualifications framework prior to the introduction of dedicated short-course

funding. A certificate consists of four subjects, and usually takes around six

months full-time study to complete. It can be used as a stand-alone

qualification, or a pathway to further study.

Places are allocated to institutions through a competitive application

process. The Government’s CourseSeeker

website lists over 500 short courses currently available, predominantly

(but not exclusively) at universities. It

appears from analysis of the university funding agreements that funding

from these earlier announcements has not yet been fully allocated.

Other measures

Industry PhDs

Budget

Paper No. 2 (p. 8) also includes $1.1 million over two years from 2020–21

to introduce an additional weighting in the Research

Training Program (RTP) funding formula for PhD students who undertake an

industry placement in the first 18 months of their enrolment.

RTP funding is provided as a block grant to universities to

provide tuition fee waivers, stipends for general living costs, and allowances

for other research degree costs for both domestic and international research

students. This additional funding is intended to provide an incentive for

universities to facilitate industry placements for research students.

The Portfolio

Budget Statements 2021–22: Budget Related Paper no. 1.4: Education, Skills and

Employment Portfolio (pp. 14, 60) indicate the RTP is funded at

approximately $1.1 billion per year over the forward estimates, and the

additional weighting will be worth approximately $30,000 to the university per

PhD graduate on completion.

Boosting the next generation of women

in STEM

As part of the Women’s Economic Security Package (Budget

Paper No. 2, pp. 81–82), $42.4 million has been allocated through the Industry,

Science, Energy and Resources Portfolio, to establish the Boosting the Next

Generation of Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM)

Program. The Program will provide 230 scholarships, co-funded with industry,

for women to pursue higher education STEM qualifications.

This measure complements a range of other initiatives being

delivered under the Advancing

Women in STEM strategy. The STEM

Equity Monitor shows women received approximately 38% of STEM degrees in

2019. However, it should be noted that this percentage is much higher in the

natural and physical sciences (58%) and agriculture, environment and related

studies (54%), compared with information technology (18%) and engineering and

related technologies (17%), which poses a challenge for initiatives which

target STEM in its entirety.

Scholarships for health and aged

care higher education courses

Higher education scholarships have also been funded in the Health

Portfolio in response to both the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry

into Mental Health and the National Suicide Prevention Adviser’s Final

Advice, and the Royal

Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. These measures, as outlined

in the Health

Portfolio 2021–22 Budget Stakeholder Pack (pp. 134 and 167) are:

- up to 280 scholarships as part of a $27.8 million investment to increase

the number of nurses, psychologists and allied health practitioners working in

mental health settings and

- as part of a $27.2 million investment to increase the number of

nurses and allied health professionals working in aged care, additional places

in the Aged Care Nursing Scholarship Program, with dedicated places for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Workforce support

through the vocational education and training sector is discussed under skills

training, elsewhere in this Budget Review.

The policy agenda

In some respects, the lack of major higher education

announcements in the Budget could have been welcomed as providing policy

stability after the long-running

funding policy deadlock was resolved in 2020 through the Job-ready Graduates Package.

However, in the context of COVID-19, the lack of action may

represent a significant missed opportunity. According

to Andrew Norton, Professor in the practice of higher education policy at

the Australian National University, another temporary boost of research funding

could have created a ‘smoother path to a smaller research system’ in the

context of declining revenue from international student fees, and minimised

premature termination of research projects. Norton also argues that ‘Tudge’s handout

of $26 million worth of short courses for a domestic market many providers

do not serve in courses they do not teach, is not going to keep them in

business’.

With policy work currently underway on university research commercialisation

and a new

international education strategy, further announcements could be

forthcoming by the end of 2021 to address these issues. However, in the

meantime, emphasis seems to have been placed largely on short courses, which the

Government has described as part of a pivot towards microcredentials.

In addition to short-course funding, the Government has

invested in microcredentials through a ‘marketplace’ for online

microcredentials announced

in June 2020. The call

for applications for the grant to build the marketplace was released in March

2021. The Government has also prioritised

‘embedding micro-credentials in the training system by funding a reasonable mix

of short courses and full qualifications’.

Despite a

lack of agreed definition, microcredentials are widely cited as a way to

support rapid skills development, including by the OECD—they

are often seen as cheaper, and more responsive to employers’ needs. New

Zealand introduced short industry-aligned microcredentials to its regulated

education and training system in 2018, while in Canada, Ontario

has introduced a number of initiatives since 2019 to develop and implement

microcredentials to help people ‘rapidly upskill and reskill for in-demand jobs’.

However, some education researchers are less convinced. Leesa

Wheelahan and Gavin Moodie have criticised the narrow instrumentalist focus

of microcredentials, raising concerns about the possible impacts for students

of removing skills development from broader contexts and frameworks of

knowledge development in higher education.

Ultimately, the success of any investment in shorter form

credentials in Australia will depend on what is funded, and how it is

accredited. Investments so far have been short term, but may signal an

intention to direct more higher education investment towards rapid upskilling

and reskilling. Much may depend on the Government’s willingness to act on its

acceptance of the recommendations of the Australian

Qualifications Framework Review Final Report (2019, p. 12), which

included revisions to the Australian

Qualifications Framework (AQF) to define and recognise shorter form

credentials such as microcredentials. The Australian Technology Network of

Universities (ATN), in collaboration with The University of Newcastle, has

welcomed short-course funding but pointed to the need for action on the AQF in

its pre-budget

submission (p. 3).

Concluding comments

This year’s higher education budget is notable largely for

the absence of new expenditure. The

Australian Academy of the Humanities has called this ‘a moment of missed

opportunity for a nation built on ingenuity and education’, stating that the

university sector has been ‘almost totally overlooked’ and ‘we cannot have a

strong workforce and a strong economy without a strong university sector’.

Although the Government appears committed to higher

education delivering job-ready graduates, including through short courses and

innovative delivery, UA

has also pointed out that this Budget confirms the cessation of funding for

the Australian Awards

for University Teaching and the Learning and Teaching Repository, which

reward good university teaching and share better practice (DESE

Portfolio Budget Statements 2021–22, p. 67). The ATN

and the University of Newcastle have also expressed disappointment at the

choice in this Budget not to build on existing short-course funding for

universities.

However, larger structural uncertainties confronting

universities and NUHEPs are likely to overshadow these issues. UA

has stated that keeping Australia’s border closed until mid-2022 poses

‘serious challenges for the nation’s universities’ and called for governments

to come together to develop a plan for the safe return of international

students. It expects ‘the picture for universities will get worse. There will

be significant flow-on effects for the nation’s research capacity and jobs

inside and outside universities’. The

Australian Academy of Science agrees with this view. While welcoming some

science investments in the Budget, it expresses concern that it ‘contains no

significant new funding for fundamental discovery science and no initiatives to

stem the loss of university science jobs’.