Budget Review 2020–21 Index

David Watt and Nic Brangwin

Defence was in the relatively unusual situation of having

some certainty about its budget well ahead of the actual Budget day. This is

because the Government set out its funding plans for Defence through the rest

of the current decade in the 2020 Defence Strategic

Update (DSU), which was released on 1 July 2020. Effectively, the

DSU was an update to the 2016

Defence White Paper and took the 2016 DWP’s ten-year defence funding model

out to 2029–30. If fulfilled, the ten-year funding model will provide Defence

with $575 billion to 2029–30. The Government provides Defence with this

enviable level of certainty about its funding in part because, as the DSU makes

clear, Australia’s strategic situation has deteriorated in recent years, but

also because the range of complex acquisition programs that Defence is running

requires long-term financial commitment to see them to fruition.

This year (2020–21) also marks the point at which the

Defence budget surpasses 2 per cent of GDP. This number has been a largely

symbolic target and, as set out in the 2016 DWP and repeated in the DSU, will

now be abandoned in order to ensure that defence funding will not be subject to

fluctuations in Australia’s GDP.

As has been the case since in recent years, the Government

has continued to adhere, with only minor fluctuations, to the funding model set

out in the 2016 DWP and the 2020 DSU. The following table sets out the DSU’s

projected funding against this year’s PBS figures.

Table 1: total defence funding—Defence

Strategic Update and Portfolio Budget Statement (PBS) ($ million)

|

|

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

| DSU |

42 151 |

46 037 |

50 170 |

53 318 |

| PBS 2020–21 |

42 746 |

45 609.9 |

49 406.3 |

52 467.3 |

Source: Department of Defence,

2020 Defence strategic update, 2020, p. 54; Australian Government, Portfolio budget statements 2020–21: budget related

paper no. 1.3A: Defence Portfolio,

p. 21.

Government funding to Defence has risen by around $3.5

billion between 2019–20 and 2020–21. This is an 8.9 per cent rise in nominal

terms and once the forecast for inflation is taken into account, 7 per cent in

real terms (calculated by deflating the nominal expenditure figure by the June

quarter Consumer Price Index, which may differ from the methodology used in the

budget papers).

Defence receives a little more than the DSU funding line in

the current year (largely because of funding for operations), but gets a little

less across the forward estimates. This seems mainly to relate to a reduction

in funding to compensate for foreign exchange fluctuations—which amounts to

$2,227.6 million across the forward estimates. The nature of this funding

means there is no impact on Defence’s buying power.

One new and useful table in the PBS is Table

4b on page 21, which provides a breakdown of Defence’s budget by ‘key cost

categories’. The table makes clear the growth in the proportion of the Defence budget

that is going into capability acquisition. The Force

Structure Plan that accompanied the DSU stated that capability

acquisitions would reach 40 per cent of the Defence budget by 2029–30. As

the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) has pointed out in volume one

of its Cost

of Defence 2020–21, this is a historic high and represents a 148 per cent

nominal increase from 2019–20.

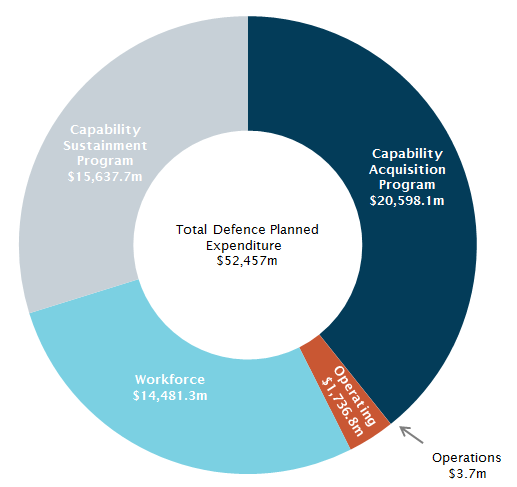

This growth is apparent in Figure 1 below, which sets out

the breakdown of the amounts for 2023–24.

Figure 1: key cost categories

forecast for 2023–24

Source: Parliamentary Library

estimates; Australian Government, Portfolio budget statements 2020–21: budget related

paper no. 1.3A: Defence Portfolio,

p. 21.

Capability

There are no new major capabilities announced in the Budget,

but with so many large capability acquisitions underway and promised funding of

$270

billion across the decade, this is not surprising. Table 55 in the PBS

(pp. 113–22) outlines the top 30 acquisition projects by 2020–21 forecast

expenditure and reveals:

- By the end of 2020–21 the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) should

have accepted 41 of its proposed 72 F-35A Joint Strike Fighters and more than

half of the approved budget of $16.7 billion budget will have been spent.

- The Air Warfare Destroyer program expects to declare final

operational capability by June 2021 and most of its $9.1 billion budget will

have been spent by that time.

- The purchase of the two replenishment vessels from Spanish

shipbuilder Navantia is expected to take a major step with the delivery of both

ships to Australia and the bulk of the $1.1 billion budget spent during the current

financial year.

- Other major shipbuilding projects—in particular the Hunter Class

Frigates and Attack Class Submarines—are much closer to the start than they are

to completion, with the bulk of the expenditure still very much in the future.

- Construction of the Offshore Patrol Vessels, the evolved Cape

Class Patrol Boats and the replacement Pacific Patrol Boats, is underway with forecast

expenditure of $464 million during the current year.

In relation to the Attack Class submarines and Hunter Class

Frigates ASPI’s Marcus

Hellyer points out that both underspent against their targets last year, particularly

the frigates. Earlier in 2020 there were suggestions that the Hunter

Class project is experiencing schedule slippage. Defence has denied there

is a problem and it appears the first

steel will be cut in 2022 at South Australia’s Osborne shipyard for what

will become HMAS Flinders. However, given the importance of the frigate build

to the Government’s plans for continuous shipbuilding, even a potential delay

must be of concern.

Budget measures

Defence is receiving supplementation of $80 million for the

current year relating to deployments in support of the COVID-19 response. Defence

itself has to find the $1 billion that the Government wants to spend to

‘accelerate defence initiatives to speed the COVID recovery’. This includes

increasing the employment of Reservists who have lost their jobs as a result of

the pandemic; a $300 million estate works program in regional Australia;

accelerated sustainment programs across a range of Australian Defence Force (ADF)

capabilities; and the acceleration of some capability platforms. This measure is

listed in Budget

Measures: Budget Paper No. 2: 2020–21, but was previously announced

by the Government on 26 August 2020.

Defence has been given an additional $10.6 million (out of

$17.7 million) across the forward estimates as a part of establishing the Joint

Transition Authority to better assist ADF members as they leave military service

and transition to civilian life. The creation of the Joint Transition Authority

was recommended by the Productivity Commission in its 2019 report A

Better Way to Support Veterans (for more details, see the Veterans’

Affairs article elsewhere in this Budget Review).

Other measures include $124.3 million across ten years for

infrastructure in the Southwest Pacific as part of the Pacific Step-up program

(see also the Budget Review 2020–21 brief, Australia’s

Foreign Aid Budget 2020–21). The establishment of a Joint Strike Fighter

Industry Program will support Australian businesses seeking work on the JSF

support and sustainment. Both measures are to be funded from the existing

Defence budget.

Operations

The

last Ministerial Statement on Defence operations was delivered to

Parliament on 5 December 2019. At that time the ADF was involved in ‘17 active

operations and activities’. Outcome 1 in the 2020–21 PBS

lists 21 international and domestic military operations; of which six are in

the Middle East, six in the

Indo-Pacific, four in Australia, two in Africa (Mali and South Sudan), one in

central Asia (Afghanistan), one in Europe (Cyprus), and one in the Antarctic.

Since the last Ministerial Statement, some operational

deployments have begun to draw down. In the Middle East, Operation Okra Task

Group Taji (Iraq) and the Air

Task Group (Iraq and Syria) completed their missions, the number of ADF personnel

deployed in Afghanistan halved to 150, and it remains to be seen whether or

not the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) replaces

HMAS Toowoomba in the Middle East maritime region.

Defence is supplemented for

the cost of operations on a ‘no-win no-loss’ basis, meaning operations

funding covers the additional costs required to conduct operations, such as

operating costs and urgent equipment acquisitions. Forward estimates for

operations funding is typically underfunded in the PBS due in some part to

operational security and the unpredictability of military operations. Only

those operations that receive funding on a no-win no-loss basis are included in

the Budget; smaller operations, such as contributions to peacekeeping missions

(up to $10 million), are funded from within the Defence budget.

The net additional cost of operations in 2020–21 is around

$727.8 million. This includes funding for the COVID-19 response, but the

largest proportion is attributed to Operation Okra in the Middle East. Given

the drawdown of task groups in Iraq and Syria, operations funding for Middle

East missions is likely to be significantly reduced in future years.

Workforce

In 2019–20 workforce was the most expensive item in the

Defence budget, at a cost of more than $12.8 billion (see the key

cost categories breakdown in the 2020–21 PBS).

While workforce costs will continue to increase—totalling more than $55.7

billion over the forward estimates—capability acquisition and sustainment costs

will surpass this, bringing the workforce share of the overall budget down from

32.9 per cent to 27.6 per cent over the forward estimates, as Table 2 below

shows.

Table 2: workforce planned

expenditure ($ million)

|

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

| Workforce |

12 877.9 |

13 410.5 |

13 766.9 |

14 108.3 |

14 481.3 |

| Total Defence planned expenditure |

39 157.7 |

42 612.4 |

45 590.6 |

49 508.4 |

52 457.6 |

| Workforce share |

32.9% |

31.5% |

30.2% |

28.5% |

27.6% |

Source: Australian Government,

Portfolio budget statements 2020–21: budget related

paper no. 1.3A: Defence Portfolio,

p. 21.

While Defence prepares a new Defence Strategic Workforce Plan

(DSWP) for consideration by the Government in 2021, the 2020 Force

Structure Plan (FSP), released with the DSU on 1 July, contains an initial

ADF workforce increase of 800 permanent personnel (RAN 650; Army 50; RAAF 100)

and an increase of 250 in the Australian Public Service (APS) civilian

workforce (which excludes additional growth in the Australian Signals Directorate,

ASD). The DSWP is expected to be released in late 2021 and will include plans

to grow the workforce between the years 2024 and 2040. Developing the science,

technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workforce appears to be a

priority area for future workforce planning.

The current

workforce total is:

- 59,109 permanent ADF

- 21,189 Reserves and

- 16,129 APS (excludes ASD personnel).

Tables

8 and 9 in the PBS (p. 26) reveal that by 2023–24 the planned workforce

total is expected to be:

- 62,726 permanent ADF

- 22,040 Reserves and

- 16,456 APS (excluding ASD personnel).

The FSP earmarked

investment of around $6.3 to $9.4 billion from 2030 to 2040 for the

‘recapitalisation of Reserves’ to boost training commensurate with the

permanent force and develop the capacity to more rapidly deploy the Reserves.

All online articles accessed October 2020

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.